Karen conflict

| Karen conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the internal conflict in Myanmar | |||||||

A KNLA medic treats IDPs in Hpapun District, Kayin State. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

show

Former: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

show

Former: |

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Since 1989: ~4,500 killed[5][6] 200,000 civilians displaced[7] | |||||||

The Karen conflict is an armed conflict in Kayin State, Myanmar (formerly known as Karen State, Burma). The conflict has been described as one of the world's "longest running civil wars".[8][9]

Karen nationalists have been fighting for an independent state known as Kawthoolei since 1949.[10] In the over seventy-year-long conflict there have been many different combatants, the most influential of which are the Karen National Union and their Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), and the Tatmadaw, the armed forces of Myanmar.[11] Hundreds of thousands of civilians have been displaced throughout the course of the conflict, 200,000 of whom have fled to neighbouring Thailand and are still currently confined to refugee camps.[7]

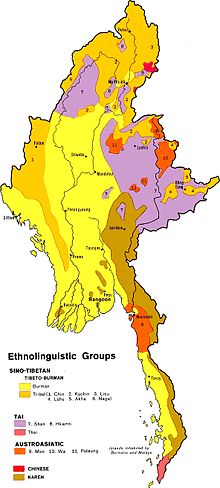

Karen people[]

The Karen people are one of the largest ethnic minorities in Myanmar. The Karen constitute a population of 5 to 7 million and around twenty different Karen dialects are recognised of which Sgaw and Pwo Karen are the two most widely spoken. Other groups of Karen are the Kayah, Bwe, Kayan, Bre, Pa-o and some other subgroups.[12] The Karen languages are part of the Tibeto-Burman languages which are a branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages.[13][14]

It is generally agreed[according to whom?] that the Karen began to arrive in what is today known as Burma around 500 BC.[citation needed] The Karen are believed to come from what is known today as Mongolia and travelled south through three river valleys: the Mekong Valley, the Irrawaddy Valley and the Salween valley.[15] The Karen traditionally have five oral legends which explain their ancestry. The word 'Karen' is derived from different Tai and Burmese names for a collective term referring to people in the forest and in the mountains. The term Karen was never used by the people who are referred to by the term today. It was not until the nineteenth century that Christian missionaries from America and British colonial officers labelled these people 'Karen'.

The Karen are not a homogenous group.[16][17] Different groups of Karen did not share the same history within the kingdoms of pre-colonial Burma or the British colonial empire. Some Karen fulfilled functions as ministers in urbanised kingdoms like the Pegu kingdom in the sixteenth century. Other Karen developed a subsistence way of living in the forests bordering Thailand and some Karen still practice this way of life. Around 20% of the Karen are Christian, whereas 75% are Buddhists. A small percentage of Karen are animist, and in the lowland river delta the so-called 'black Karen', a small minority, is Muslim.[18] The Sgaw speaking population constitutes around 80% of the total Karen population and they are mainly Buddhist.[19]

The speakers of Pwo Karen live in the plains of central and lower Burma and were assimilated into the dominant Mon social system throughout history. These 'Mon-Karen' or Talaing Kayin had a special status and were an essential part of Mon court life. The Bama Kayin or Sgaw Karen were either absorbed into Burmese society or pushed towards the mountains bordering Thailand in the east and Southeast of Burma by the Burmese population. The Karen living in Burma’s eastern hills named the Dawna Range and the Tenasserim Hills bordering Thailand developed their own distinct society and history. The hill Karen communities developed a subsistence way of life.[20]

Today about three million Karen live in the Irrawaddy river delta and they have developed an urbanised society based on the agriculture of rice. Karen communities are religiously, linguistically, culturally separated and geographically dispersed. Some scholars have claimed ‘the’ Karen do not exist.[21]

Colonial era[]

The outbreak of the Karen conflict has its roots in the British colonial era. In the nineteenth century certain Karen hill tribes were Christianized by American missionaries. During the conquering of Burma in the nineteenth century the British made use of the existing antagonism between Burmans and Karens. Karen assisted British armies in the Anglo-Burmese wars.[22] At the same time it was American missionaries who Christianized Sgaw karen and helped these Karen to climb higher positions in Burmese society.[23]

The Christian Karen developed a loyalist relationship with the British regime. Through Christian education the Karen were taught English and how to read and write. This process led to 'Karenization' by the British colonial administrative body. Exclusion of ethnic Burmese from the army and other colonial state bodies had a big impact on Burmese resisting the colonial state.[24][25][26]

Conversion to Christianity[]

The first American missionary arrived in Burma in 1813. The first Karen was converted to Christianity on 16 May 1828.[27] American Baptists quickly discovered that the Sgaw Karen were more easy to convert to Christianity than the Pwo. The Pwo Karen had just been converted to Buddhism en masse before the arrival of the missionaries.[28]

The introduction to and the acceptance of Christianity by the Sgaw Karen provided a way to distinguish themselves from Burmese Buddhists. To convert more Karen the missionaries learned Karen. Subsequently, they modernised the Karen script using the Burmese alphabet. Dr. Jonathan Wade was involved in producing dictionaries and establishing grammar rules for both the Pwo and Sgaw Karen dialects. In 1853 Dr. Francis Mason published the first bible in the Sgaw Karen Language. A Pwo Karen bible was also published by reverend D.L Brayton.[29]

Between 1860 – 1890 many Karen were converted to Christianity. In 1875, the Baptist college was opened in Rangoon, later this school would be known as 'Karen College'. Schools were built and through education the Christian Karen learned English. This group of Karen were thus able to improve their economic, educational and social situation.[30] In 1922 Reverend H. Marshall wrote:

"A considerable number of Karen young men and a few young women are college graduates and are leading useful lives in various communities, as may be seen by looking over the list of officers in government positions in the Education, Forest, Police, Military and subordinate branches."[31]

The American missionaries also tried to explain the origin of the Karen. By this process the missionaries created the category of Karen and Karen history and traditions. The missionaries modernised the Karen script and translated the Bible into Pwo and Sgaw Karen. The modernisation of the Karen script and the growth in literacy among Sgaw karen led to a stimulation of secular Karen literature and journals. In 1842 the Baptist Mission began publication in Sgaw Karen of a monthly magazine called 'The Morning Star' (Hsa Tu Gaw) which continued all the way up the take over of general Ne Win in 1962.[32][33] The missionaries taught these people to feel group pride and dignity. This in turn led to a Karen national consciousness.[34]

The American missionaries particularly focused on the hill tribes and not on the valley peoples of Burma. The loyalist relationship which subsequently developed between the British and these groups of Karen also stemmed from the position these Karen held within Burmese history. Never before had these hill tribe Karen developed their own kingdom or gained any political or economical influence. Aligning themselves with the British was seen as an opportunity to improve their lives. At some point the 'thirst for Christian education', as written by a missionary was so big the 'Eastern Karen' demanded a permanent teacher. Otherwise they would apply to other missionary churches.[35][36]

The relationship between the Karen and the colonial British created much resentment among the Burman population. At the same time the authority of the Burmese state in the nineteenth century pushed the Karen more towards the British. Britain did not control the whole of Burma before 1886. In Burmese controlled territory Karen were not allowed to educate themselves at these American Baptists established schools. Many Karen were tortured and killed. The Karen who allied themselves to the British and helped them to gain total control of Burma in 1886.[37]

Literacy, knowledge of the English language and access to Christian education led the Sgaw Karen to be advantaged over other Karen linguistic groups of Buddhist Karen by the British colonial government.[38] Their Christian identity helped to develop a loyalist relationship with the British. At the same time Christian missionaries taught these people to be Karen and thus not Burman. The primary result of the Christianization of the Sgaw Karen is the construction of a Karen identity and their political influence over other Karen groups. Due to their improved economical and social status the Sgaw Karen were the first group of Karen to develop a feeling for a Karen nation. It was this group who created the first Karen political organisations and therefore always dominated the Karen nationalist movement and its organisation.[39][40][41]

Colonial policy and its implications[]

The British conquered Burma between 1826 and 1886. The Karen provided important military support for the British in these Anglo-Burmese wars. In the first Anglo-Burmese war in 1824 to 1826 Karen provided guidance to British armies. Burmese authorities tried to punish the involved Karen for this. Some Karen fled to areas now occupied by the British or put up some form of resistance.

After the British conquered the territory which was to be the future state of Burma the British colonial state had a hard time pacifying the country. Burmese resisted the authority of the colonial state on a continual basis. After the Burmese capital of Mandalay was conquered by the British in the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885 with help of some Karen, Burmese in the southern delta started a rebellion. During this crucial period in which the British proclaimed martial law, American missionaries successfully lobbied to recruit more Karens as auxiliaries to put down Burmese rebellions throughout the colony. The success surprised the British and the missionaries proudly commented on the results.[42][43]

The colonial policy was driven by the quest for resources for the capitalist market system of the expanding British empire. The riverplains of Burma were used for the production of agricultural products, while the hill areas surrounding these river plains were of much less economic value to the British. The colonial policy based these two political entities developed. Central Burma was governed through direct rule and the frontier area, where most ethnic minorities lived and still live was governed through indirect rule.[44]

To pacify the country mainly Indian, Karen and other ethnic minorities were used. The 'direct and indirect rule' policy has had a huge influence on political developments in postcolonial Burma.[45]

In the years 1930–1932, Burmese rebelled against the colonial state in what became known as Saya San Rebellion. The Karen helped to repress this rebellion. Other rebellions Christian and other Karen helped to suppress were the 1936 student strike and the general strike of 1938.[46]

In 1937 Burma finally reached the status of an individual colony. Burma was not to be governed from India from that point onwards. Finally a space was created to include Burmese people into the colonial administrative and military bodies. The Burmese nationalist movement started developing in the 1920 and by 1937 saw entering the colonial army as 'collaborating' with the British. Thus the 'Burmese' army continued to be made out of Burma's ethnic minorities.[47]

Political organizations of the Karen[]

The Karen were the first ethnic group in Burma to establish political organizations. Already in 1840 the Karen Baptist Convention (KBC) was established. This Christian organization trained Karen at conferences which were attended by Karen who had rarely left their village. The first Karen political organisation was established in 1881 and carried the name Karen National Association (KNA). The KNA aimed to represent all Karen regardless of language, religion or location. From the beginning however the KNA was dominated by Christian Karen.[48]

The Buddhist wing of the Buddhist Karen National Association (BKNA) was only established in 1939. The KNA developed close relations with the British and the BKNA established relations with the Burmese. The KNA assisted the British army in the last Anglo-Burmese war in 1886. Pwo Buddhists resisted the efforts of Christian Karen to represent them in any political organization. There were also Pwo Karen however who were a member of the KNA and were represented by them.[49][50]

The KNA became an important political organization in colonial Burma. In the 1920s the Karen nationalist movement (and at the same time the Burmese nationalist movement) gained momentum. Dr. San C. Po, a lawyer educated in the West and ethnic Karen made the first public announcement of the Karen's aim to create their own state in 1928.[51] The same year a KNA member, Saw Tha Aye Gyi, wrote the Karen national anthem.[52]

In 1937 a Karen flag was created, thus symbolising the Karen peoples as a nation. The colonial government appointed the inauguration day of this flag as a public holiday. The British colonial government endorsed the Karen view of their history by these event. The Karen identified themselves as the first inhabitants of Burma. A claim which has had a variation of political consequences in modern-day Burma.[53]

The KNA developed into the Karen National Union or KNU in February 1947, one year before independence. The KNU charter of 1947, like the KNA charter of 1881 included all Karen, regardless of subgroup, religion or language.[54] In 1947 the KNU formed the armed wing of the KNU, the Karen National Liberation Army or KNLA. The KNU-KNLA has functioned as a government for half a century. Running the area of what is known as Karen State practically as a government, including levying taxes.

The majority of the Karen never supported an armed conflict and have never affiliated with the armed struggle of the KNU-KNLA. The Karen National Union (KNU) controlled areas rarely constitute a Karen majority. Most Karen actually lived outside KNU dominated territory in the past six decades. This fact has always been the main problem for the unification of the Karen in one Karen State.[55]

The organisational structure of the KNU has been so successful it has been copied by other insurgent groups in Burma. Each unit of the KNU was self-supporting. Not only the armed units, but also the hospitals and schools were self-supporting. The strength of this strategy is that it is hard to erase such a movement since it is very spread out and lacks a centre. The weakness and disadvantage of the KNU has been that KNU units had trouble getting help from their neighbouring KNU units.[56]

WWII and its aftermath[]

Before the outbreak of World War II the Karen nationalist movement was moving completely opposite of the Burmese nationalist movement. The Karen were imagined to be Christian and loyal to Britain. The Burmese nationalist movement was anti-imperialist and Buddhist. In 1941 just before the outbreak of the Second World War in Asia the Karen in the army constituted 35% while the Karen represented 9.34% of the population in Burma. Ethnic Burmans made up 23.7% of the total in the army while they accounted for 75.11% of the total population in Burma. This means that the recruitment of Karen per head of the population was much higher than the recruitment of Burmans.[57]

Japanese occupation[]

The invasion of the Japanese army in Burma in 1942 was the start of a destructive period for Burma's people and its institutions. To control the country the Japanese allowed a Burmese Independence Army (BIA) to be formed. It was the first time in Burma's history that a specific Burmese national army was formed. For the first time ethnic Burmans were allowed to form a political and military institute. This helped to strengthen Burmese nationalist discourse. One characteristic of the BIA is that they excluded all ethnic minorities because they were associated with the British colonial government. The first Karen battalion was only established in 1943.[58] The establishment of the BIA was to have a big influence on Burma's future since the war in Burma was fought along ethnic lines.[59]

The Christian Karen mostly stayed loyal to the British throughout the Japanese occupation and the Second World War. The Karen were of particular importance for British units for their knowledge of the jungle and their bravery. Under guidance and with support of the British a Karen resistance army was built in the eastern hills of Burma. By 1945 their numbers would reach 12,000 Karen soldiers. This Karen army was trained to fight the Japanese and thus the Burmans who cooperated with them. Some British officials made promises to Karen leaders that after the war they would gain independence.[60][61]

These trained Karen established a resistance network with the Karen in the river delta to fight the Japanese. The Japanese discovered this and heavily punished the Karen. During the retreat of the Japanese army in December 1944, Karen armed units were crucial in the defeat of the Japanese at Taungoo. In the Dawna Range the Karen managed to resist Japanese war efforts for a long time. The 12.000 man strong army actually managed to capture and/or kill a retreating army of 50.000 Japanese.[62][63]

After the war there was a strong sense among Karen soldiers that they would be granted their own state by the British because of their war efforts. The sense among Karen veterans that they deserved at least self-determination explains partly the failure of later peacetalks between the KNU and the Tatmadaw.[64]

A remarkable event during the war was the slaughtering of Karen by BIA troops in 1942. Four hundred villages were destroyed and the violence is estimated to have resulted in as much as 1800 deaths. This event exacerbated the existing tension between ethnic Karen and ethnic Burmans, which Aung San himself tried to smooth out in later years.[65]

Return of the colonial state[]

After the defeat of the Japanese the British returned to Burma to continue their colonial rule. But the British returned to a devastated Burma. State institutions were destroyed, the agricultural sector was in ruins and there was no central authority. Burma was ruled by local warlords and a wide variation of armed groups. The BIA under command of Aung San emerged as one of the strongest parties from this chaotic period. To merge the different factions Lord Mountbatten proposed the creation of a two wing army.[66]

One wing would consist of Burmans and the other wing of non-Burmans, both would be under the command of a British officer. Eventually the army which was established in mid-1945 in reality were two armies. Each which its own history, traditions and different maps of the future nation. Four Burman Battalions were established together with two Karen people, two Kachin people and 2 Chin people battalions. Aung San's demand for retaining his former PBF units together in the new army was confirmed in the Kandy Conference of 6–7 September 1945 in Kandy, Sri Lanka.[67]

The British followed a policy of creating two post-colonial political units in the territory of Burma after World War II. However the influence of Aung San and his Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF) backed up by the political party Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL) grew bigger. The Karen and other minorities were afraid to be forced into a state which would be dominated by Burmans. In August 1945 Karen leaders Saw Ba U Gyi and Sydney Loo-Nee proposed to a British army official to create a new state called 'Karenistan'. In September 1945 a group of Karen drafted a memorial demanding the creation of the United Frontier Karen States.[68]

The biggest dilemma for Karen in this period and the future was the territory inhabited by Karen. Mary Callahan, an expert on Burmese Tatmadaw history, writes: "However, some combination of confidence (due to their experiences in prewar and wartime western institutions) and fear of mistreatment by the Burman majority kept Karen leaders in the army and in the society from moving toward a compromise with the AFPFL."[69] In 1946 the Goodwill mission left for London. A delegation of four Karen went to London to state the Karen's case to the British government. They returned without having reached any agreement. One reason for this might be the rise of other ethnic demands from the Kachin, Chin and Shan people.[70]

Aung San however tried to incorporate all ethnic minorities into a future Burma. On 12 February 1947 Aung San signed the Panglong Agreement with representatives of the Shan, Kachin and Chin peoples. A formal representative delegation of the Karen was absent. Supposedly because the Karen leadership did not believe in the Burman leaderships' determination for the creation of a Karen State. But the KNU's leadership by this time was boycotting all official government organised gatherings.[49][71]

A few days prior to the Panglong Agreement the KNA, Baptist KNA, Buddhist KNA, the KCO and its youth wing established the Karen National Union or the KNU. The KNU used a sharper tone, demanding independence and boycotting constituent Assembly elections. This boycott effectively removed a Karen voice from the critical debates which were to come in the future.[72]

In 1947 the Burmese government produced a new constitution, but this document failed to address and resolve the Karen question.[73] On 17 July 1947 the KNU headquarter in Rangoon ordered the establishment of karen fighting units, known as Karen National Defence Organisation or KNDO's. The KNU also established an underground communication line with the Karen Rifles within the Burmese army. In October 1947 the AFPFL government proposed to the KNU to create a Karen state but the KNU refused. The KNU demanded more territory than was included in the proposal.[74]

The British feared to lose control of the Burman wing of the army. To control the Burman wing of the army the British official Thomas saw the Karen as the answer. Thomas most likely hoped that the British trained Karen officials would use their higher positions to gain influence in the anti-British Burman squadrons. The 'Karenization' of the army led Karen to hold the highest positions. The chief of staff General Smith Dun, the chief of the air force Saw Shi Sho and the chief of operations were all ethnic Karen. The chief of operation was trained in Sandhurst Brig. Saw Kya Doe. All the supporting services, the staff, supply and ammunition depots, the artillery and signal corps were commanded by Karen officers. Despite the dominance of Karen in high positions, the Karen leadership was afraid of Burmese retaliation and refrained from radical reorganisation of the Burmese wing of the army.[75][76]

Burmese independence, 1948[]

On 4 January 1948 Burma gained its independence from Britain. State authority and state structures were still very fragile. In February 1948 four hundred thousand Karen in a peaceful demonstration showed their solidarity with the creation of a Karen State.[77] Within three months after independence, the Communist Party Burma began an armed rebellion and similarly some Karen separatist groups started an armed struggle for independence. Many members of the KNDO's were former wartime veterans and were in the anti-Japanese (and thus anti-Burmese) resistance.[78]

The creation of the KNDO and the AFPFL government's distrust of the Karen 'collaborators' enhanced the ancient old tensions between the Karen and the Burmans. The British Service Mission (BSM) advised the Burmese military after independence on arms purchase and other things. BSM personnel particularly favoured Karens for promotion and positions of authority within the army. Burmans thought of this as suspicious.[79]

Sporadic fighting took place between Karen militias and Burman troops in early 1948. However the Karen led Burmese army helped to suppress the communist rebellion throughout 1948 and thus supported the AFPFL government. In May 1948 the AFPFL government made a concession to the communist rebels and opened the door to the communist to participate in national politics. Karen army and political leaders, mostly rightist oriented, interpreted this as a proof of the AFPFL government that it was impossible for Karen to live within a state controlled by this government.[80]

In June 1948 former PBF officers started organising meetings to find a solution to the growing power of Karen in the Burmese army and to stop the communist rebellion. From May to August there were minor outbreaks of violence between government controlled Karen and Burman troops, both fighting the communist. A split in the third Burif troops on 10 August 1948 immediately exacerbated the tension between Burmese officers and the Karen military leadership.[81]

The Karen leadership distrusted the intent of the Third Burifs led by the later president of Burma, Ne Win. These army desertions resulted in a stronger Karen grip on the army. The army and the KNDO by this time controlled large parts of the countryside. On 14 August 1948, Karen armed militias took over Twante near Rangoon. Other Karen militias took over Thaton and Kyaikkami a week later. On 30 August, the KNDO took over Thaton and a KNDO group took over Moulmein.[82]

1948 was a year characterised by violence in Burma. Every single group owning arms tried to reach for more authority through violence. In general two camps could be identified. One camp could be labelled as rightist and pro-western. These were Karen army leadership, the KNDO, Karen Peace Guerillas (local defence units, of which some members would today be labelled as criminals), most of the police and the Union Auxiliary Forces. The other camp could be defined as leftist and anti-British.[83]

This group was made up by the AFPFL government, some battalions of Burmans within the government army, the Sitwundan (a police/army force established by prime minister U-Nu in the summer of 1948 as a reaction to the Karen dominated army and the rightist/pro-western police force)[84] and local village defence units and local political armies that rejected communists and rightists. The last four months of 1948 saw an escalation of violence throughout Burma. All sides fought for their vision of Burma. Some British officers stayed in the jungle of Eastern Burma to support the struggle for independence in Burma. One of them was arrested in Rangoon on 18 September.[85]

The Burmese press blew the incident up stating a Karen rebellion was at hands and this led to more Burmese violence towards the Karen. On 19 September, Tin Tut, a leader of rightist levies and viewed as an ally by many Karen, was assassinated in Rangoon. General Smith Dun acted as a mediator for a peace deal between KNDO units and the AFPFL government in November. This outraged pro-AFPFL officers within the army.[86]

On 13 November 1948 the KNU demanded an independent Karen-Mon state which would surround Rangoon. The Burmese press saw this as a move against the Union government. The escalation of tension and violence resulted in larger incidents in December. On Christmas Eve a locally raised ethnic Burman Sitwundan group threw handgrenades into a church in Palaw, killing eighty Christian Karen. The following weeks hundreds of Karen were murdered by Sitwundan and Socialist groups for which KNDO troops starting retaliating.[87]

Outbreak of the Karen conflict, 1949[]

The AFPFL government relied on Karen, Kachin and Chin battalions to fight insurgencies throughout Burma in the period following the WWII.[88] Karen troops still fought for the AFPFL government up until December 1948. In January 1948 the then prime minister of Burma U Nu and Karen leader Saw Ba U Gyi toured the Irrawaddy riverdelta to prevent escalation of violence. Ordered by Gen. Smith Dun and with permission of U Nu, local KNDO units took the Twante channel, connecting Rangoon with the Irrawaddy river, from communist rebels. Resembling the chaos of those days, the Rangoon newspapers reported this to be the beginning of the Karen insurgency. This event largely attributed to the rising tension of the time between Karens and Burmans.[89]

Later in January 1948 KNDO units raided the arm depots of the army in the KNDO controlled town of Insein, near Rangoon. Sitwundan units and Burmese students and others moved in on Insein during January and skirmishes occurred. KNDO leaders reacted with calling in more enforcements from outlying districts. KNDO units trained out in the open in Insein Township and set up road blocks in the area. Burmans living in Insein lost patience and started arming themselves, not relying on the government to protect them. Confrontations spread to wherever Burmans and Karens were living close together, mostly in the river delta. In mid-January 150 Karen were killed in Taikkyi Township. Lacking central authority local KNDO units attacked Burmese targets in retaliation. At the same time the Burmese press inflamed public opinion.[90]

Colonel Min Maung, a Karen, was asked to create a diversion to break the stalemate by KNU leader Saw Ba U Gyi. On 27 January 1949, Colonel Min Maung's First Karen Rifles seized the town of Taungoo. Karen naval commander Saw Jack attacked Pathein and other Karen troops seized the town of Pyu the following day. On 30 January, the KNDO was outlawed by the Union government of Burma and the Karen were purged out of the army two days later. Prime Minister Nu expelled all Karen leaders from their military posts, replacing general Smith Dun with Ne Win. The remainder of Karen in the official armed forces either joined the rebellion or were put into camps.[91]

The Insein skirmishes escalated into a battle by 31 January 1949. Taungoo wasn't retaken by the government until March 1949 and the town of Insein not until May 1949, after heavy losses on both sides.[92] On 14 June 1949 the KNU proclaimed the Karen Free State or Kawthoolei together with the Four Principles (see below). These principles have formed the heart of the KNU insurgency ever since[93]

Development of the Karen conflict[]

The Karen National Union declared war to the Burmese government on 31 January 1949. Ever since the start the conflict has been characterised by seasonal dependent fighting, internal struggles within the KNU and atrocities being committed by both sides. The KNU/KNLA army has been divided into seven brigades. Occasionally a brigade Commander would act independently from the KNU leadership.

Shortly after the outbreak of the conflict Then KNU president Saw Ba U Gyi created the Four Principles:[94] 1. Surrender is out of the question. 2. Recognition of the Karen State must be completed. 3. We shall retain our arms. 4. We shall determine our destiny.

These hard-line principles have prevented the KNU from compromising and making any concessions towards the Tatmadaw. In the 1950s the conflict was well under way. A remarkable development was that prominent Karen such as General Smith Dun refused to join the rebellion. The KNU booked several military successes against the Burmese army. Yet this changed throughout the 1950s. In 1954 the British Service Mission (BSM) was closed. The BSM was a legacy of the colonial time and many employees sympathised with the Karen. Furthermore, during this decade the Tatmadaw reorganised and transformed into a modern standing army. The Tatmadaw introduced the strategy in the late 1960s. The strategy is aimed to cut off rebellious groups of their four sources of food, funds, intelligence and recruits. This strategy has been proven to be very effective.[95][96] In 1963–1964 peace talks were held with no result.

The 1970s the KNU struggled with several internal rebellions like the rise of the Telecon. This religious sect was found in the nineteenth century. The leaders of Telecon have presented themselves as the true Karen, thus posing a threat to KNU leadership. In 1972 Telecon leaders were executed after an invitation from the KNLA's Sixth Brigade Commander. Another example of internal KNU conflict is the case of Lt-Col. Thu Mu Hae. Thu Mu Hae's Sixteenth Battalion under the command of the KNLA's Sixth Brigade Commander had been acting independently since the late 1980s. Officials from the KNU could only enter Kawkareik township if they were accompanied by fifty soldiers or more, because Thu Mu Hae had in effect a private warlord army.[97][98]

The Karen Conflict has been portrayed by the outside world as a conflict which was fought in the hills along the Burma–Thailand border. But in the 1950s and 1960s Karen insurgency groups also attacked Burmese targets in the Irrawaddy riverdelta. The Four Cuts strategy of the Tatmadaw eventually forced the Karen armed units in the delta to continue fighting from their stronghold in the border hills.[96] Since 1966 General Bo Mya was the KNU leader in the eastern division of the Karen conflict. A remarkable turnaround was in 1976, the year when General Bo Mya became the KNU's president. The KNU reformed under Gen. Bo Mya and after 1976 the KNU developed a strong anti-communist character.[99]

In 1976 the KNU changed its demand for an independent Karen State or Kawthoolei into a demand for more autonomy. The history of the Karen insurgency was also rewritten and the history of the communist inspired wing of the KNU, led by the Karen veteran and the KNU's strategist Mahn Ba Zan, was left out. Mahn Ba Zan had led the Karen insurgency in the riverdelta in the 1950s and 1960s.[100]

The KNU reached the height of its power in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 1989 a ceasefire proposal designed by the Tatmadaw was refused by the Karen National Union.[101] In 1994 peace talks between the KNU leadership and the Tatmadaw were held again. But the KNU leadership refused to accept a ceasefire. Former KNU Foreign Affairs Secretary David Taw has described how in 1993 exile Burmese politicians told General Bo Mya not to pursue a ceasefire with the military government. They expected that the 'international community' would soon start to support the KNU through diplomacy.[102] In December 1994 a thousand KNU soldiers established the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army or DKBA. These Buddhists troops had been complaining for years about anti-Buddhist discrimination by local Christian KNU officers.[103]

These Buddhists Karen soldiers were dissatisfied with the Christian leadership and corruption of the KNU and their decision to stop the ceasefire negotiations. A final split was triggered by a dispute over the building of a Buddhist pagoda on a military strategic hill near Manerplaw. With the help of the Tatmadaw this group overran the headquarter of the KNU in the city of Manerplaw, near the border with Thailand. The DKBA developed into a stronger and bigger organisation than the KNU within several years.[104][105]

In 1995, 1996 and 1997 several meetings were held between the KNU leadership and military officials of the Tatmadaw. However General Bo Mya and other hard-liners refused to accept any government constructed ceasefire proposal. In 1997 the KNU leadership hardened their position, demanding the release of political prisoners and more political dialogue. This resulted in further decimation of the strength of the KNU. In 1997 former KNU-KNLA armed units established the Karen Peace Force or KPF.[106] In 1998 the forestry minister of the KNU established the P'doh Aung San Group. In the same year a small ceasefire group was founded in Northern Karen State in Taungoo district.[107]

In the Southern part of Karen State or Myanmar two twin brothers established God's Army in February 1997 in the immediate aftermath of this offensive. The twin brothers led villagers and old KNLA members of the Fourth Brigade of the Tenasserim Region into armed clashes with government troops, separated from the KNU's leaders. Eventually the two hundred strong militia occupied a hospital in Thailand's Ratchaburi and broke up after this.[108]

After the fall of Manerplaw the KNU also lost its stronghold just north of it called Kawmoora. A direct result of all this was that the KNU lost most of its income derived from tax revenue, logging deals and cross-border trade.[109] The loss of its financial base was also due to changing international relations. The threat of Communism disappeared in the 1990s, thus the US and Thai government changed policies. When the KNU attacked an oil pipeline in Karen state in 1995, the US government gave an official warning to the KNU for the first time.[110]

Democratic Karen Buddhist Army[]

From the start the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) has been affiliated with the Burmese army. The DKBA always orientated for support to the Burmese government. The DKBA has never developed a unifying Karen nationalist political policy. Partly due to its lack in English language skills the DKBA lacks international support. Unlike the KNU the DKBA does not use terms like democratic, liberal, human rights and other terms welcomed by Western democratic discourse. The DKBA controlled areas teach Burmese instead of Karen, thus following official government policy. Most of the DKBA's armed units have been transformed into Border Guard Forces or BGF's.[111]

Role of Thailand and the United States[]

The Thai government historically used Karen State as a buffer zone against the Burmese. After the Second World War the Thai were afraid of a communist insurgency developing from a union between Thai and Burmese communists, supported by China. Thus the Thai and US government supported Karen rebellions through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. The US government however also supported the Burmese government to fight communists. The US government provided weapons and American produced helicopters. The KNU has claimed that these weapons have been used against them.[112]

General Bo Mya once described the KNU as Thailands' 'foreign legion', because the KNU guarded the border the organisation prevented Thai and Burmese communists from unification. The strong shift to the right in 1976 under Bo Mya was a strategy to gain support from the Thai government.[113] Thailands' policy changed in the 1990s when the Thai government started engaging its neighbours national government as equals. In 1997 Burma became a member of the ASEAN. The Thai government subsequently turned away from supporting the Karen armed groups.[55][114][115]

The first Karen started to cross the border with Thailand in 1984 as a result from a major Four Cuts offensive by the Tatmadaw which lasted up to 1990.[116] By the mid-1990s tens of thousands of Karen refugees were living in camps along the Thai border. After the fall of Manerplaw in 1995, 10,000 refugees crossed the border, most of them Karen. The Karen Conflict has been able to run for several decades because it has profited from being located in a border area. The introduction of the Burmese Way to Socialism helped to create a financial base for the KNU which has profited greatly from bordertrade with Thailand.[117] The KNU levied taxes on in- and outgoing products. Besides that the KNU and other Karen armed groups have used the refugee camps in Thailand as sources for limited material support. KNU/KNLA family members received shelter in and supplies from the camps.[118]

After the fall of Manerplaw in 1995, the KNU leadership has moved their headquarters to the border town of Mae Sot in Thailand. This has caused tension between the KNU leadership and the KNU officers on the ground within Burma. There is also disagreement amongst the Brigade leaders themselves, particularly between the Third and Fifth Brigades and the Fourth Brigade in the South, in the Tenasserim region. The Tatmadaw opened a new offensive in 1997. This again resulted in a new stream of Karen refugees towards Thailand. The border at Mae Sot was closed for a short period in 2010 because of rising tensions between the KNU and the DKBA.[119]

The organisational structure of the KNU was so successful it has been copied by other insurgent groups in Burma. Each unit of the KNU was self-supporting. Not only the armed units, but also the hospitals and schools were self-supporting. The strength of this strategy is that it is hard to erase such a movement since it is very spread out and lacks a centre. The weakness and disadvantage of the KNU has been that KNU units had trouble getting help from their neighbouring KNU units.[56]

Refugees[]

At least two million people of many different ethnic groups are internally displaced in Burma. Another two million ethnic minorities from Burma have found refuge in neighbouring countries. A large portion of this latter group is Karen. The first Karen refugees started to arrive in Thailand in 1984.[120] The KNU has greatly benefited from the refugee camps in Thailand. The KNU has used these camps as safehavens and has been provided with food and other materials through family members and friends who stayed in the camps.[121]

Around two hundred thousand Karen and Karenni are placed in nine refugee camps within Thailand on the Myanmar–Thailand border.[122] Since 2006 a resettlement program has been set up. 73,775 Karen people were resettled in July 2011 to mostly Western countries, predominantly the United States of America. In January 2011 the Thai Burmese Border Consortium (TBBC) set the total number of refugees at 141,549 people.[123]

Conflict since 2000[]

The Karen split up into many different armed units after the 1990s. The Karen National Union (KNU) was heavily weakened after this decade. In 2004 substantial ceasefire talks were held again between Gen. Bo Mya and Burmese general Khin Nyunt. Unfortunately, Khin Nyunt was expulsed from the government. In 2005 two more peace talks were held, but it was clear that the new government under the leadership of Than Shwe was not interested in establishing a ceasefire. In 2006 the long-term leader and Second World War veteran General Bo Mya died.[50][124]

Old-time general-secretary of the KNU, Padoh Mahn Sha Lah Phan took over Bo Mya's function. Padoh Mahn Sha was important for political relations and the reorganisation of the KNU. On 14 February 2008, he was assassinated. In 2007 Major General Htin Maung left with a sizeable portion of the KNLA Seventh Brigade. This group now calls themselves KNU-KNLA Peace Council. If further decimated the strength and influence of the KNU.[50][125]

On 20 March 2010, 2 people were killed and 11 were wounded in a blast on a bus in Karen state.[126]

In November 2010 Myanmar–Thailand border areas saw an upsurge in fighting following elections in November 2010. Twenty thousand people fled over the border to Thailand in November 2010. For the first time in fifteen years, the KNU and the DKBA were united to fight the Tatmadaw.[127] But as of early 2011 the KNU is only one in seven Karen armed factions that are active in fighting. The KNU barely holds any territory inside Burma and the future of the organisation and the Karen struggle for independence is uncertain.[128] An initial ceasefire was reached on 12 January 2012 in Hpa-an and fighting has stopped in nearly all Karen State.[129]

The KNU signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) with the government of Myanmar on 15 October 2015, along with seven other insurgent groups.[130] However, in March 2018, the government of Myanmar violated the agreement by sending 400 Tatmadaw soldiers into KNU-held territory to build a road connecting two military bases.[131] Armed clashes erupted between the KNU and the Myanmar Army in the Ler Mu Plaw area of Hpapun District, resulting in the displacement of 2,000 people.[132] On 17 May 2018, the Tatmadaw agreed to "temporarily postpone" their road project and to withdraw troops from the area.[133]

The KNU resumed its fight against the Myanmar government following the 2021 military coup. On 27 April 2021, KNU insurgents captured an army camp on the west bank of the Salween River, which forms Myanmar's border with Thailand. The Tatmadaw later retaliated with airstrikes on KNU positions. There were no casualties reported by either side.[134]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ "DKBA appoints new Commander-in-Chief". Mizzima. 22 April 2016. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard, p. 88

- ^ Burma center for Ethnic Studies, Jan. 2012, "Briefing Paper No. 1" http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/BCES-BP-01-ceasefires(en).pdf Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Myanmar Peace Monitor: Stakeholders – DKBA-5". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ "Government of Myanmar (Burma) - KNU". ucdp.uu.se. Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Government of Myanmar (Burma) - DKBA 5". ucdp.uu.se. Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b South, Burma's Longest war. p. 10 and Shirley L. Worland, "Displaced and misplaced or just displaced: Christian Displaced Karen Identity after Sixty Years of War in Burma" PhD. Philosophy at The University of Queensland, March 2010, p. 23

- ^ Patrick Winn (13 May 2012). "Myanmar: ending the world's longest-running civil war". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Callahan M.P., Making Enemies. War and Statebuilding in Burma. Cornell University Press (Ithaca/London, 2013)

- ^ South, A., "Burma’s Longest war. Anatomy of the Karen conflict." Transnational Institute and Burma Center Netherlands: Amsterdam, 2011, p. 6

- ^ Pattisson, Pete (16 January 2007). "On the run with the Karen people forced to flee Burma's genocide". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Gravers, M., "The Karen Making of a Nation." in: Asian Forms of the Nation, Stein Tonnesson and Hans Antlöv, eds. Curzon Press: Richmond, Surrey, 1996. pp. 237 – 269, p. 241.

- ^ Jorgensen, Anders Baltzer, Foreword in: The Karen People of Burma. A study in Anthropology and Ethnology H. I. Marshall Bangkok: White Lotus Press 1997. Original work from 1922. p. V – XI

- ^ South, p.10

- ^ Worland, "Displaced and misplaced or just displaced: Christian Displaced Karen Identity after Sixty Years of War in Burma" PhD. Philosophy at The University of Queensland, March 2010, p.8

- ^ Hinton, P., "Do the Karen really exist?" in: J. McKinnon and W. Bhruksasri (eds.), Highlanders of Thailand (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1983), 155 – 168

- ^ South, p. 2

- ^ Harriden, J., “Making a name for themselves: “Karen identity and the politization of ethnicity in Burma”, in: The Journal of Burma Studies, vol. 7, 2002, pp. 84 – 144, p. 85, 92–95.

- ^ Thawnghmung, A. Maung, The Karen Revolution in Burma: Diverse Voices, Uncertain Ends. Washington: East – West Center, 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Christie, Clive J., “Anatomy of a Betrayal: The Karens of Burma.” In: I.B. Tauris (Eds.), A Modern History of Southeast Asia. Decolonization, Nationalism and Separatism (pp. 54–80). London, England, 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Hinton, P., "Do the Karen really exist?" in: J. McKinnon and W. Bhruksasri (eds.), Highlanders of Thailand (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 155 – 168.

- ^ Brant, Charles S. and Mi Mi Khaing, “Missionaries among the Hill Tribes of Burma”, in: Asian Survey, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Mar. 1961), p. 44, 46 – 50.

- ^ Worland, "Displaced and misplaced or just displaced, p. 27

- ^ Callahan, M., Making Enemies. War and State Building in Burma. United States of America: Cornell University Press, 2003, p. 34 – 36

- ^ Holliday, I., Burma Redux: Global Justice and the Quest for Political reform in Myanmar. Columbia University Press: New York, 2011, p. 34, 131, 211

- ^ Myint-U, T., The Making of Modern Burma, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001.p. 131, 211

- ^ Jorgensen, Anders Baltzer, Foreword in: The Karen People of Burma. A study in Anthropology and Ethnology H. I. Marshall Bangkok: White Lotus Press 1997. Original work from 1945. p. V – XI and page 296

- ^ Marshall, Harry I., The Karen people of Burma. A study in Anthropology and Ethnology White Lotus Press: Bangkok, 1997 (original published in 1945)p. 300

- ^ Marshall, The Karen people of Burma." p. 300, 306–309

- ^ Marshall, The Karen people of Burma." p. 300, 306–309

- ^ Marshall, p. 309

- ^ Callahan, Making Enemies, p. 34

- ^ Brant, Charles S. and Mi Mi Khaing, “Missionaries among the Hill Tribes of Burma”, in: Asian Survey, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Mar. 1961), p. 49

- ^ Worland, p. 15

- ^ Aung-thwin, M. and M. Aung-Thwin, A History of Myanmar since ancient times. Traditions and Transformations. Reaktion Books: London, 2013, p. 192

- ^ Brant and Khaing, “Missionaries”, in: Asian Survey, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Mar. 1961), p. 44 and 46

- ^ Worland, p. 15-16. On these pages a lot of scholars are quoted who support this information.

- ^ Keyes, Charles. ‘Afterwords: The Politics of “Karen-Ness” in Thailand’. ed. Claudio O. Delang, 210–9. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003, p. 211

- ^ Harriden, “Making a name for themselves:”, in: The Journal of Burma Studies, vol. 7, 2002, p. 94 – 98

- ^ Callahan,Making Enemies. p. 34

- ^ Brant and Khaing, “Missionaries among the Hill Tribes of Burma”, in: Asian Survey, p. 44 and 50

- ^ Aung-thwin and Aung-Thwin, A History of Myanmar. London, 2013, p. 180

- ^ Brant and Khaing, p. 49-50 and for British historical narratives on the role of Christian Karen please see: Worland, p. 13

- ^ Smith, Martin J., Burma: insurgency and the politics of ethnicity. Zed Books: London, 1999. p. 52

- ^ Aung-thwin and Aung-Thwin, p. 182 and 191

- ^ Callahan, p. 36

- ^ Callahan, p. 73

- ^ Gravers, M., "The Karen Making of a Nation." in: Asian Forms of the Nation, Stein Tonnesson and Hans Antlöv, eds. Curzon Press: Richmond, Surrey, 1996. pp. 237 – 269, p. 238

- ^ Jump up to: a b Worland, p. 18

- ^ Jump up to: a b c South, p. 8

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 51.

- ^ Worland, p. 19

- ^ Worland, p. 19

- ^ Worland, p. 27

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rajah, A., "Contemporary Developments in Kawthoolei: The Karen and Conflict Resolution in Burma." Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter 19, 1992. (http://www.nectec.or.th/thai-yunnan/19.html#3 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith, Burma. p. 391 – 392.

- ^ Callahan, p. 42

- ^ Callahan, p. 58

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 64.

- ^ Callahan, p.71

- ^ BBC documentary 'The History of the Karen people', https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0SRyirsQkkU Archived 18 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Callahan, p.71

- ^ BBC documentary 'The History of the Karen people', https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0SRyirsQkkU Archived 18 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 62 – 64 and 72.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 62 – 64.

- ^ Callahan, p.95 – 97

- ^ Callahan, p.95 – 97

- ^ Callahan, p.105

- ^ Callahan, p.105

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 73 – 75

- ^ Myint-U, Thant, The Making of Modern Burma, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001, p. 94

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 83.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 77.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 86.

- ^ Callahan, p.105, 112–3 and 119

- ^ Aung-thwin and Aung-Thwin, p. 184

- ^ Worland, p. 20

- ^ Callahan, p. 118–123

- ^ Callahan, p. 118–123

- ^ Callahan, p. 125–130

- ^ Callahan, p. 125–130

- ^ Callahan, p. 125–130

- ^ Callahan, p.129 – 132

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 110–117.

- ^ Callahan, p.129 – 132

- ^ Callahan, p.129 – 132

- ^ Callahan, p.129 – 132

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 116.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 111.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 117.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 118.

- ^ Callahan, p. 132–134

- ^ Brouwer, Jelmer & Joris van Wijk (2013) "Helping hands: external support for the KNU insurgency in Burma" in: Small Wars & Insurgencies, 24:5, pp. 835–856, p. 837

- ^ Pedersen, D., Secret Genocide. Voices of the Karen of Burma. Maverick House Publisher: Dunboyne, Ireland, 2011, p.7

- ^ Callahan, M., Making Enemies. War and State Building in Burma. United States of America: Cornell University Press, 2003, p. 149 and 168

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith, Burma. p. 391.

- ^ South, p. 37-38

- ^ Callahan, p. 209

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 294 – 295 and 297.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 298.

- ^ Myint-U, Thant, The Making of Modern Burma, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001, 66

- ^ South, p. 35

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 446.

- ^ South, p. 8, 10, 16 and 19

- ^ Worland, p. 21

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 449.

- ^ South, p.37

- ^ South, p.37

- ^ South, p. 10, 14 and 16

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 448.

- ^ South, p. 13, 36, 44

- ^ Pedersen, Secret Genocide.p. 19

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 297 – 298.

- ^ South, p. 20 and 34

- ^ Brouwer & van Wijk "Helping hands" p. 840

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 395.

- ^ Smith, Burma. p. 283 – 284.

- ^ South, p. 20

- ^ South, p.42 and 44

- ^ Lang, Hazel J., Fear and Sanctuary. Burmese refugees in Thailand. Cornell Southeast Asia Program: United States of America, 2002, p. 11

- ^ Brouwer & van Wijk "Helping hands" p. 842 – 845

- ^ Worland, p. 23

- ^ Brouwer & van Wijk "Helping hands", p. 845

- ^ Worland, p. 22

- ^ Worland, p. 22

- ^ "Myanmar: Bombings and Pre-Election Tensions". 15 April 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Pedersen, D., Secret Genocide. p. 270

- ^ South, p.2, 14 and 45

- ^ Brouwer & van Wijk "Helping hands" p. 839

- ^ "Myanmar Signs Historic Cease-Fire Deal With Eight Ethnic Armies". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Sandford, Steve (31 May 2018). "Conflict Resumes in Karen State After Myanmar Army Returns". Voice of America. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Sandford, Steve (31 May 2018). "Karen Return to War in Myanmar". Voice of America. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Nyein, Nyein (17 May 2018). "Tatmadaw Agrees to Halt Contentious Road Project in Karen State". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ "Fighting erupts in Myanmar; junta to 'consider' ASEAN plan". Reuters. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Aung-thwin, M. and M. Aung-Thwin, A History of Myanmar since ancient times. Traditions and Transformations. Reaktion Books: London, 2013.

- Brant, Charles S. and Mi Mi Khaing, “Missionaries among the Hill Tribes of Burma”, in: Asian Survey, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Mar. 1961), pp. 44 – 51.

- Brouwer, Jelmer & Joris van Wijk (2013) "Helping hands: external support for the KNU insurgency in Burma" in: Small Wars & Insurgencies, 24:5, pp. 835–856.

- Callahan, M., Making Enemies. War and State Building in Burma. United States of America: Cornell University Press, 2003.

- Callahan, M., “Myanmar’s perpetual junta. Solving the Riddle of the Tatmadaw’s Long Reign.” In: New Left Review, vol. 60, nov/dec 2009, pp. 27 – 63.

- Christie, Clive J., “Anatomy of a Betrayal: The Karens of Burma.” In: I.B. Tauris (Eds.), A Modern History of Southeast Asia. Decolonization, Nationalism and Separatism(pp. 54–80). London, England, 2000.

- Gravers, M., "The Karen Making of a Nation." in: Asian Forms of the Nation, Stein Tonnesson and Hans Antlöv, eds. Curzon Press: Richmond, Surrey, 1996. pp. 237 – 269.

- Harriden, J., “Making a name for themselves: “Karen identity and the politization of ethnicity in Burma”, in: The Journal of Burma Studies, vol. 7, 2002, pp. 84 – 144.

- Hinton, P., "Do the Karen really exist?" in: J. McKinnon and W. Bhruksasri (eds.), Highlanders of Thailand (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 155 – 168.

- Keyes, Charles. ‘Afterwords: The Politics of “Karen-Ness” in Thailand’. ed. Claudio O. Delang, 210–9. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

- Lang, Hazel J., Fear and Sanctuary. Burmese refugees in Thailand. Cornell Southeast Asia Program: United States of America, 2002.

- Marshall, Harry I., The Karen people of Burma. A study in Anthropology and Ethnology White Lotus Press: Bangkok, 1997 (original published in 1945).

- Myint-U, Thant, The Making of Modern Burma, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2001.

- Pedersen, D., Secret Genocide. Voices of the Karen of Burma. Maverick House Publisher: Dunboyne, Ireland, 2011.

- Petry, Jeffrey L.,The Sword of the Spirit: Christians, Karens, Colonists, and the Creation of a Nation of Burma. University Microfilms international: Ann Arbor, 1995.

- Rajah, A., "Contemporary Developments in Kawthoolei: The Karen and Conflict Resolution in Burma." Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter 19, 1992. (http://www.nectec.or.th/thai-yunnan/19.html#3)

- Selth, A., "Race and resistance in Burma, 1942 – 1945" in: Modern Asian Studies Vol. 20, issue 3, 1987, pp. 483 – 507.

- Silverstein, J., "Ethnic Protest in Burma: Its Causes and Solutions." in: Protest movements in South and South-East Asia: Traditional and Modern Idioms of Expression. Rajeswari Ghose, ed. Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, 1987. pp. 81 – 94.

- Smith, Martin J., Burma: insurgency and the politics of ethnicity. Zed Books: London, 1999.

- South, A., Burma’s Longest war. Anatomy of the Karen conflict. Transnational Institute and Burma Center Netherlands: Amsterdam, 2011, pp. 1–53.

- Thawnghmung, A. Maung, The Karen Revolution in Burma: Diverse Voices, Uncertain Ends. Washington: East – West Center, 2008.

- "Burma's Ethnic Challenge: From Aspirations to Solutions." Burma Policy Briefing no. 12, Transnational Institute and Burma Centre Netherlands: Amsterdam, 2013. pp. 1 – 20.

- Worland, Shirley L., "Displaced and misplaced or just displaced: Christian Displaced Karen Identity after Sixty Years of War in Burma" PhD. Philosophy at The University of Queensland, March 2010, p. 1 – 323.

Documentary[]

Further reading[]

- Charney, Michael W., A History of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Falla, J., True Love and Bartholomew: Rebels on the Burmese Border. Cambridge University Press: New York, 1991.

- Fong, Jack. Revolution as Development: The Karen Self-Determination Struggle Against Ethnocracy (1949–2004). Boca Raton, FL: Brownwalker Press.

- Fredholm, M., Burma: Ethnicity and Insurgency. Praeger: Westport,1993.

- Holliday, I., Burma Redux: Global Justice and the Quest for Political reform in Myanmar. Columbia University Press: New York, 2011.

- Hlaing, Kyaw Yin, Prisms on the Golden Pagoda. Perspectives on national reconciliation in Myanmar. National University of Singapore Press: Singapore, 2014.

- Keyes, Charles F. (ed), Ethnic Adaptation and Identity: The Karen on the Thai Frontier with Burma. Institute for the Study of Human Issues: Philadelphia, 1979.

- Keyes, Charles F., The Golden Peninsula: Culture and Adaptation in Mainland Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, 1995.

- Lintner, B., Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency since 1948. White Lotus Press: Bangkok, 1994

- MacDonald, M., Kawthoolei Dreams, Malaria Nights: Burma's Civil War. White Lotus Press: Bangkok, 1999.

- Marks, Thomas A., "The Karen Revolt in Burma." in: Issuas and Studies vol. 14, issue 12, pp. 48 – 84.

- Rajah, A., "Ethnicity, Nationalism, and the Nation-State: The Karen in Burma and Thailand." in: Ethnic Groups Across National Boundaries in Mainland Southeast Asia. Gehan Wijeyewardene, ed. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 1990. pp. 102 – 133. ISBN 981-3035-57-9.

- Renard, Ronald D., "The Karen Rebellion in Burma." in: Secessionist movements in comparative perspective. Ralph R. Premadas, S.W.R. De A. Samarasinghe and Alan Anderson, eds. Pinter: London, 1990. pp. 95 – 110.

- Smith, Martin J., "Ethnic Politics and regional Development in Myanmar: The Need for new approaches" in: Myanmar: Beyond Politics to Societal imperatives. ISEAS Press: Singapore, 2005.

- South, A., Ethnic Politics in Burma: States of Conflict London: Routledge, 2008.

- South, A., “Karen Nationalist Communities: The “Problem” of Diversity””, in: Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 29, no. 1 (April 2007), pp. 55 – 76.

- Steinberg, David I., Burma/Myanmar. What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press: New York, 2013.

- Stern, T., "Ariya and the Golden Book: A millenarion Buddhist Sect among the Karen." in: The Journal of Asian Studies vol. 27, issue 2, pp. 297 – 328.

- Tambiah, Stanley J., “Ethnic conflict in the world today.” In: American Ethnologist, Vol. 16, No. 2 (May 1989), pp. 335–349.

- Taylor, Robert H., The State in Burma. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1987.

- Thomson, Curtis N., “Political Stability and Minority Groups in Burma”, in: Geographical Review, Vol. 85, no. 3 (July 1995), pp. 269 – 285.

- Tinker, H. (ed.), Burma: The Struggle for Independence, 1944 – 1948: Documents from Official and Private Sources. 2 vols. H.M.S.O: London, 1983.

- Walton, Matthew J., “Ethnicity, Conflict, and history in Burma: The Myths of Panglong” in: Asian survey, vol. 48, no. 6 (November/December 2008), pp. 889–910.

- Yhome, K., Myanmar. Can the generals resist change? Rupa & Co.: New Delhi, 2008.

- Karen people

- History of Myanmar (1948–present)

- Rebel groups in Myanmar

- Politics of Myanmar

- Internal conflict in Myanmar

- Wars involving Myanmar

- Separatism in Myanmar