Israeli–Palestinian conflict

| Israeli–Palestinian conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Israeli conflict and the Iran–Israel proxy conflict | |||||||||

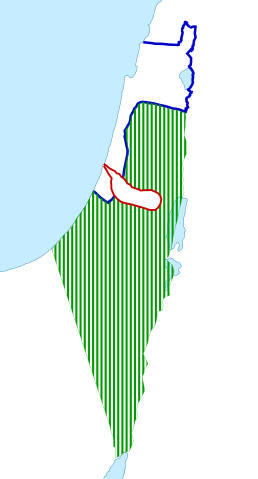

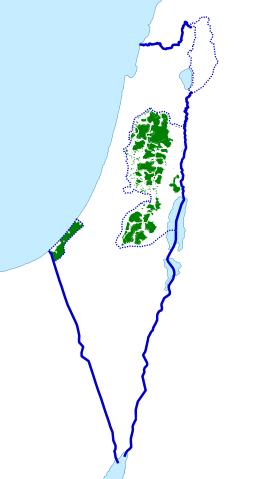

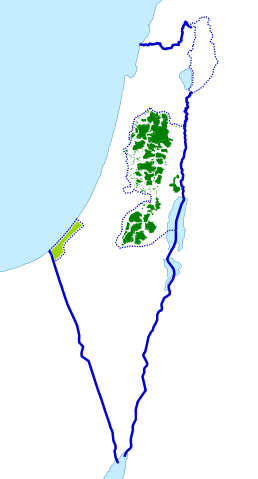

Central Israel and Area C (blue), the part of the West Bank under full Israeli control, 2011 (For a more up-to-date, interactive map, see here). | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

|

show

Supported by: |

show

Supported by: | ||||||||

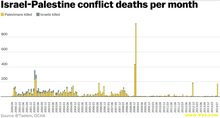

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, with the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip reaching 54 years of conflict.[7] Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process.[8][9][10][11]

Public declarations of claims to a Jewish homeland in Palestine, including the 1897 First Zionist Congress and the 1917 Balfour Declaration, created early tension in the region. At the time, the region had a small minority Jewish population, although this was growing via significant Jewish immigration. Following the implementation of the Mandate for Palestine, which included a binding obligation on the British government for the "establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people" the tension grew into sectarian conflict between Jews and Arabs.[12][13] Attempts to solve the early conflict culminated in the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine and the 1947–1949 Palestine war, marking the start of the wider Arab–Israeli conflict. The current Israeli-Palestinian status quo began following Israeli military occupation of the Palestinian territories in the 1967 Six-Day War.

Despite a long-term peace process, Israelis and Palestinians have failed to reach a final peace agreement. Progress was made towards a two-state solution with the 1993–1995 Oslo Accords, but today the Palestinians remain subject to Israeli military occupation in the Gaza Strip and in 165 "islands" across the West Bank. Key issues that have stalled further progress are security, borders, water rights, control of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements,[14] Palestinian freedom of movement,[15] and Palestinian right of return. The violence of the conflict, in a region rich in sites of historic, cultural and religious interest worldwide, has been the subject of numerous international conferences dealing with historic rights, security issues and human rights, and has been a factor hampering tourism in and general access to areas that are hotly contested.[16] Many attempts have been made to broker a two-state solution, involving the creation of an independent Palestinian state alongside the State of Israel (after Israel's establishment in 1948). In 2007, the majority of both Israelis and Palestinians, according to a number of polls, preferred the two-state solution over any other solution as a means of resolving the conflict.[17]

Within Israeli and Palestinian society, the conflict generates a wide variety of views and opinions. This highlights the deep divisions which exist not only between Israelis and Palestinians, but also within each society. A hallmark of the conflict has been the level of violence witnessed for virtually its entire duration. Fighting has been conducted by regular armies, paramilitary groups, terror cells, and individuals. Casualties have not been restricted to the military, with a large number of civilian fatalities on both sides. There are prominent international actors involved in the conflict. A majority of Jews see the Palestinians' demand for an independent state as just, and think Israel can agree to the establishment of such a state.[18] The majority of Palestinians and Israelis in the West Bank and Gaza Strip have expressed a preference for a two-state solution.[19][20][unreliable source?] Mutual distrust and significant disagreements are deep over basic issues, as is the reciprocal skepticism about the other side's commitment to upholding obligations in an eventual agreement.[21]

The two parties currently engaged in direct negotiation are the Israeli government, led by Naftali Bennett, and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), headed by Mahmoud Abbas. The official negotiations are mediated by an international contingent known as the Quartet on the Middle East (the Quartet) represented by a special envoy, that consists of the United States, Russia, the European Union, and the United Nations. The Arab League is another important actor, which has proposed an alternative peace plan. Egypt, a founding member of the Arab League, has historically been a key participant. Jordan, having relinquished its claim to the West Bank in 1988 and holding a special role in the Muslim Holy shrines in Jerusalem, has also been a key participant.

Since 2006, the Palestinian side has been fractured by conflict between two major factions: Fatah, the traditionally dominant party, and its later electoral challenger, Hamas, which also operates as a militant organization. After Hamas's electoral victory in 2006, the Quartet conditioned future foreign assistance to the Palestinian National Authority (PA) on the future government's commitment to non-violence, recognition of the State of Israel, and acceptance of previous agreements. Hamas rejected these demands,[22] which resulted in the Quartet's suspension of its foreign assistance program, and the imposition of economic sanctions by the Israelis.[23] A year later, following Hamas's seizure of the Gaza Strip in June 2007, the territory officially recognized as the PA was split between Fatah in the West Bank and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The division of governance between the parties had effectively resulted in the collapse of bipartisan governance of the PA. However, in 2014, a Palestinian Unity Government, composed of both Fatah and Hamas, was formed. The latest round of peace negotiations began in July 2013 and was suspended in 2014.

In May 2021, amidst rising tensions, the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis began with protests that escalated into rocket attacks from Gaza and airstrikes by Israel.

Background

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict has its roots in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the birth of major nationalist movements among the Jews and among the Arabs, both geared towards attaining sovereignty for their people in the Middle East.[25] The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine.[26] The collision between those two movements in southern Levant upon the emergence of Palestinian nationalism after the Franco-Syrian War in the 1920s escalated into the Sectarian conflict in Mandatory Palestine in 1930s and 1940s, and expanded into the wider Arab–Israeli conflict later on.[27]

The return of several hard-line Palestinian Arab nationalists, under the emerging leadership of Haj Amin al-Husseini, from Damascus to Mandatory Palestine marked the beginning of Palestinian Arab nationalist struggle towards establishment of a national home for Arabs of Palestine.[28] Amin al-Husseini, the architect of the Palestinian Arab national movement, immediately marked Jewish national movement and Jewish immigration to Palestine as the sole enemy to his cause,[29] initiating large-scale riots against the Jews as early as 1920 in Jerusalem and in 1921 in Jaffa. Among the results of the violence was the establishment of the Jewish paramilitary force Haganah. In 1929, a series of violent anti-Jewish riots was initiated by the Arab leadership. The riots resulted in massive Jewish casualties in Hebron and Safed, and the evacuation of Jews from Hebron and Gaza.[25]

In the early 1930s, the Arab national struggle in Palestine had drawn many Arab nationalist militants from across the Middle East, such as Sheikh Izaddin al-Qassam from Syria, who established the Black Hand militant group and had prepared the grounds for the 1936 Arab revolt. Following the death of al-Qassam at the hands of the British in late 1935, tensions erupted in 1936 into the Arab general strike and general boycott. The strike soon deteriorated into violence and the bloodily repressed 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine against the British and the Jews.[27] In the first wave of organized violence, lasting until early 1937, most of the Arab groups were defeated by the British and forced expulsion of much of the Arab leadership was performed. The revolt led to the establishment of the Peel Commission towards partitioning of Palestine, though it was subsequently rejected by the Palestinian Arabs. The two main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, accepted the recommendations but some secondary Jewish leaders did not like it.[30][31][32]

The renewed violence, which had sporadically lasted until the beginning of World War II, ended with around 5,000 casualties, mostly from the Arab side. With the eruption of World War II, the situation in Mandatory Palestine calmed down. It allowed a shift towards a more moderate stance among Palestinian Arabs, under the leadership of the Nashashibi clan and even the establishment of the Jewish–Arab Palestine Regiment under British command, fighting Germans in North Africa. The more radical exiled faction of al-Husseini however tended to cooperation with Nazi Germany, and participated in the establishment of a pro-Nazi propaganda machine throughout the Arab world. Defeat of Arab nationalists in Iraq and subsequent relocation of al-Husseini to Nazi-occupied Europe tied his hands regarding field operations in Palestine, though he regularly demanded that the Italians and the Germans bomb Tel Aviv. By the end of World War II, a crisis over the fate of the Holocaust survivors from Europe led to renewed tensions between the Yishuv and the Palestinian Arab leadership. Immigration quotas were established by the British, while on the other hand illegal immigration and Zionist insurgency against the British was increasing.[25]

On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted Resolution 181(II)[33] recommending the adoption and implementation of a plan to partition Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the City of Jerusalem.[34] On the next day, Palestine was already swept by violence. For four months, under continuous Arab provocation and attack, the Yishuv was usually on the defensive while occasionally retaliating.[35] The Arab League supported the Arab struggle by forming the volunteer-based Arab Liberation Army, supporting the Palestinian Arab Army of the Holy War, under the leadership of Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and Hasan Salama. On the Jewish side, the civil war was managed by the major underground militias – the Haganah, Irgun and Lehi, strengthened by numerous Jewish veterans of World War II and foreign volunteers. By spring 1948, it was already clear that the Arab forces were nearing a total collapse, while Yishuv forces gained more and more territory, creating a large scale refugee problem of Palestinian Arabs.[25] Popular support for the Palestinian Arabs throughout the Arab world led to sporadic violence against Jewish communities of the Middle East and North Africa, creating an opposite refugee wave.

History

Following the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel on 14 May 1948, the Arab League decided to intervene on behalf of Palestinian Arabs, marching their forces into former British Palestine, beginning the main phase of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[34] The overall fighting, leading to around 15,000 casualties, resulted in cease-fire and armistice agreements of 1949, with Israel holding much of the former Mandate territory, Jordan occupying and later annexing the West Bank and Egypt taking over the Gaza Strip, where the All-Palestine Government was declared by the Arab League on 22 September 1948.[27]

Through the 1950s, Jordan and Egypt supported the Palestinian Fedayeen militants' cross-border attacks into Israel, while Israel carried out reprisal operations in the host countries. The 1956 Suez Crisis resulted in a short-term Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and exile of the All-Palestine Government, which was later restored with Israeli withdrawal. The All-Palestine Government was completely abandoned by Egypt in 1959 and was officially merged into the United Arab Republic, to the detriment of the Palestinian national movement. Gaza Strip then was put under the authority of the Egyptian military administrator, making it a de facto military occupation. In 1964, however, a new organization, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), was established by Yasser Arafat.[34] It immediately won the support of most Arab League governments and was granted a seat in the Arab League.

The 1967 Six-Day War exerted a significant effect upon Palestinian nationalism, as Israel gained military control of the West Bank from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt. Consequently, the PLO was unable to establish any control on the ground and established its headquarters in Jordan, home to hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, and supported the Jordanian army during the War of Attrition, which included the Battle of Karameh. However, the Palestinian base in Jordan collapsed with the Jordanian–Palestinian civil war in 1970. The PLO defeat by the Jordanians caused most of the Palestinian militants to relocate to South Lebanon, where they soon took over large areas, creating the so-called "Fatahland".

Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon peaked in the early 1970s, as Lebanon was used as a base to launch attacks on northern Israel and airplane hijacking campaigns worldwide, which drew Israeli retaliation. During the Lebanese Civil War, Palestinian militants continued to launch attacks against Israel while also battling opponents within Lebanon. In 1978, the Coastal Road massacre led to the Israeli full-scale invasion known as Operation Litani. Israeli forces, however, quickly withdrew from Lebanon, and the attacks against Israel resumed. In 1982, following an assassination attempt on one of its diplomats by Palestinians, the Israeli government decided to take sides in the Lebanese Civil War and the 1982 Lebanon War commenced. The initial results for Israel were successful. Most Palestinian militants were defeated within several weeks, Beirut was captured, and the PLO headquarters were evacuated to Tunisia in June by Yasser Arafat's decision.[27] However, Israeli intervention in the civil war also led to unforeseen results, including small-scale conflict between Israel and Syria. By 1985, Israel withdrew to a 10 km occupied a strip of South Lebanon, while the low-intensity conflict with Shia militants escalated.[25]Those Iranian-supported Shia groups gradually consolidated into Hizbullah and Amal, operated against Israel, and allied with the remnants of Palestinian organizations to launch attacks on Galilee through the late 1980s. By the 1990s, Palestinian organizations in Lebanon were largely inactive.[citation needed]

The first Palestinian uprising began in 1987 as a response to escalating attacks and the endless occupation. By the early 1990s, international efforts to settle the conflict had begun, in light of the success of the Egyptian–Israeli peace treaty of 1982. Eventually, the Israeli–Palestinian peace process led to the Oslo Accords of 1993, allowing the PLO to relocate from Tunisia and take ground in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, establishing the Palestinian National Authority. The peace process also had significant opposition among radical Islamic elements of Palestinian society, such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, who immediately initiated a campaign of attacks targeting Israelis. Following hundreds of casualties and a wave of radical anti-government propaganda, Israeli Prime Minister Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli fanatic who objected to the peace initiative. This struck a serious blow to the peace process, from which the newly elected government of Israel in 1996 backed off.[25]

Following several years of unsuccessful negotiations, the conflict re-erupted as the Second Intifada in September 2000.[27] The violence, escalating into an open conflict between the Palestinian National Security Forces and the Israel Defense Forces, lasted until 2004/2005 and led to approximately 130 fatalities. In 2005, Israeli Prime Minister Sharon ordered the removal of Israeli settlers and soldiers from Gaza. Israel and its Supreme Court formally declared an end to occupation, saying it "had no effective control over what occurred" in Gaza.[36] However, the United Nations, Human Rights Watch and many other international bodies and NGOs continue to consider Israel to be the occupying power of the Gaza Strip as Israel controls Gaza Strip's airspace, territorial waters and controls the movement of people or goods in or out of Gaza by air or sea.[36][37][38]

In 2006, Hamas won a plurality of 44% in the Palestinian parliamentary election. Israel responded it would begin economic sanctions unless Hamas agreed to accept prior Israeli-Palestinian agreements, forswear violence, and recognize Israel's right to exist, which Hamas rejected.[39] After internal Palestinian political struggle between Fatah and Hamas erupted into the Battle of Gaza (2007), Hamas took full control of the area.[40] In 2007, Israel imposed a naval blockade on the Gaza Strip, and cooperation with Egypt allowed a ground blockade of the Egyptian border

The tensions between Israel and Hamas escalated until late 2008, when Israel launched operation Cast Lead upon Gaza, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties and billions of dollars in damage. By February 2009, a ceasefire was signed with international mediation between the parties, though the occupation and small and sporadic eruptions of violence continued.[41]

In 2011, a Palestinian Authority attempt to gain UN membership as a fully sovereign state failed. In Hamas-controlled Gaza, sporadic rocket attacks on Israel and Israeli air raids still take place.[42][43][44][45] In November 2012, the representation of Palestine in UN was upgraded to a non-member observer State, and its mission title was changed from "Palestine (represented by PLO)" to "State of Palestine".

Peace process

Oslo Accords (1993)

In 1993, Israeli officials led by Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leaders from the Palestine Liberation Organization led by Yasser Arafat strove to find a peaceful solution through what became known as the Oslo peace process. A crucial milestone in this process was Arafat's letter of recognition of Israel's right to exist. In 1993, the Oslo Accords were finalized as a framework for future Israeli–Palestinian relations. The crux of the Oslo agreement was that Israel would gradually cede control of the Palestinian territories over to the Palestinians in exchange for peace. The Oslo process was delicate and progressed in fits and starts, the process took a turning point at the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and finally unraveled when Arafat and Ehud Barak failed to reach agreement at Camp David in July 2000. Robert Malley, special assistant to US President Bill Clinton for Arab–Israeli Affairs, has confirmed that while Barak made no formal written offer to Arafat, the US did present concepts for peace which were considered by the Israeli side yet left unanswered by Arafat "the Palestinians' principal failing is that from the beginning of the Camp David summit onward they were unable either to say yes to the American ideas or to present a cogent and specific counterproposal of their own".[46] Consequently, there are different accounts of the proposals considered.[47][48][49]

Camp David Summit (2000)

In July 2000, US President Bill Clinton convened a peace summit between Palestinian President Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Barak reportedly put forward the following as "bases for negotiation", via the US to the Palestinian President; a non-militarized Palestinian state split into 3–4 parts containing 87–92%[note 1] of the West Bank including only parts of East Jerusalem, and the entire Gaza Strip,[50][51] The offer also included that 69 Jewish settlements (which comprise 85% of the West Bank's Jewish settlers) would be ceded to Israel, no right of return to Israel, no sovereignty over the Temple Mount or any core East Jerusalem neighbourhoods, and continued Israel control over the Jordan Valley.[52][53]

Arafat rejected this offer.[50][54][55][56][57][58] According to the Palestinian negotiators the offer did not remove many of the elements of the Israeli occupation regarding land, security, settlements, and Jerusalem.[59] President Clinton reportedly requested that Arafat make a counter-offer, but he proposed none. Former Israeli Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben Ami who kept a diary of the negotiations said in an interview in 2001, when asked whether the Palestinians made a counterproposal: "No. And that is the heart of the matter. Never, in the negotiations between us and the Palestinians, was there a Palestinian counterproposal."[60] In a separate interview in 2006 Ben Ami stated that were he a Palestinian he would have rejected the Camp David offer.[61]

No tenable solution was crafted which would satisfy both Israeli and Palestinian demands, even under intense US pressure. Clinton has long blamed Arafat for the collapse of the summit.[62] In the months following the summit, Clinton appointed former US Senator George J. Mitchell to lead a fact-finding committee aiming to identify strategies for restoring the peace process. The committee's findings were published in 2001 with the dismantlement of existing Israeli settlements and Palestinian crackdown on militant activity being one strategy.[63]

Developments following Camp David

Following the failed summit Palestinian and Israeli negotiators continued to meet in small groups through August and September 2000 to try to bridge the gaps between their respective positions. The United States prepared its own plan to resolve the outstanding issues. Clinton's presentation of the US proposals was delayed by the advent of the Second Intifada at the end of September.[59]

Clinton's plan eventually presented on 23 December 2000, proposed the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state in the Gaza strip and 94–96 percent of the West Bank plus the equivalent of 1–3 percent of the West Bank in land swaps from pre-1967 Israel. On Jerusalem, the plan stated that "the general principle is that Arab areas are Palestinian and that Jewish areas are Israeli." The holy sites were to be split on the basis that Palestinians would have sovereignty over the Temple Mount/Noble sanctuary, while the Israelis would have sovereignty over the Western Wall. On refugees the plan suggested a number of proposals including financial compensation, the right of return to the Palestinian state, and Israeli acknowledgment of suffering caused to the Palestinians in 1948. Security proposals referred to a "non-militarized" Palestinian state, and an international force for border security. Both sides accepted Clinton's plan[59][64][65] and it became the basis for the negotiations at the Taba Peace summit the following January.[59]

Taba Summit (2001)

The Israeli negotiation team presented a new map at the Taba Summit in Taba, Egypt in January 2001. The proposition removed the "temporarily Israeli controlled" areas, and the Palestinian side accepted this as a basis for further negotiation. With Israeli elections looming the talks ended without an agreement but the two sides issued a joint statement attesting to the progress they had made: "The sides declare that they have never been closer to reaching an agreement and it is thus our shared belief that the remaining gaps could be bridged with the resumption of negotiations following the Israeli elections." The following month the Likud party candidate Ariel Sharon defeated Ehud Barak in the Israeli elections and was elected as Israeli prime minister on 7 February 2001. Sharon's new government chose not to resume the high-level talks.[59]

Road Map for Peace

One peace proposal, presented by the Quartet of the European Union, Russia, the United Nations and the United States on 17 September 2002, was the Road Map for Peace. This plan did not attempt to resolve difficult questions such as the fate of Jerusalem or Israeli settlements, but left that to be negotiated in later phases of the process. The proposal never made it beyond the first phase, whose goals called for a halt to both Israeli settlement construction and Israeli–Palestinian violence. Neither goal has been achieved as of November 2015.[66][67][68]

Arab Peace Initiative

The Arab Peace Initiative (Arabic: مبادرة السلام العربية Mubādirat as-Salām al-ʿArabīyyah) was first proposed by Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia at the Beirut Summit (2002). The peace initiative is a proposed solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict as a whole, and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in particular.[69]

The initiative was initially published on 28 March 2002, at the Beirut Summit, and agreed upon again in 2007 in the Riyadh Summit.

Unlike the Road Map for Peace, it spelled out "final-solution" borders based explicitly on the UN borders established before the 1967 Six-Day War. It offered full normalization of relations with Israel, in exchange for the withdrawal of its forces from all the occupied territories, including the Golan Heights, to recognize "an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital" in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, as well as a "just solution" for the Palestinian refugees.[70]

A number of Israeli officials have responded to the initiative with both support and criticism. The Israeli government has expressed reservations on 'red line,' issues such as the Palestinian refugee problem, homeland security concerns, and the nature of Jerusalem.[71] However, the Arab League continues to raise it as a possible solution, and meetings between the Arab League and Israel have been held.[72]

Present status

The peace process has been predicated on a "two-state solution" thus far, but questions have been raised towards both sides' resolve to end the dispute.[73] An article by S. Daniel Abraham, an American entrepreneur and founder of the Center for Middle East Peace in Washington, US, published on the website of the Atlantic magazine in March 2013, cited the following statistics: "Right now, the total number of Jews and Arabs living... in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza is just under 12 million people. At the moment, a shade under 50 percent of the population is Jewish."[74]

Israel's settlement policy

Israel has had its settlement growth and policies in the Palestinian territories harshly criticized by the European Union citing it as increasingly undermining the viability of the two-state solution and running in contrary to the Israeli-stated commitment to resume negotiations.[75][76] In December 2011, all the regional groupings on the UN Security Council named continued settlement construction and settler violence as disruptive to the resumption of talks, a call viewed by Russia as a "historic step".[77][78][79] In April 2012, international outrage followed Israeli steps to further entrench the Jewish settlements in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, which included the publishing of tenders for further settler homes and the plan to legalize settler outposts. Britain said that the move was a breach of Israeli commitments under the road map to freeze all settlement expansion in the land captured since 1967. The British Foreign Minister stated that the "Systematic, illegal Israeli settlement activity poses the most significant and live threat to the viability of the two state solution".[80] In May 2012 the 27 foreign ministers of the European Union issued a statement which condemned continued Israeli settler violence and incitement.[81] In a similar move, the Quartet "expressed its concern over ongoing settler violence and incitement in the West Bank," calling on Israel "to take effective measures, including bringing the perpetrators of such acts to justice."[82] The Palestinian Ma'an News agency reported the PA Cabinet's statement on the issue stated that the West, including East Jerusalem, were seeing "an escalation in incitement and settler violence against our people with a clear protection from the occupation military. The last of which was the thousands of settler march in East Jerusalem which included slogans inciting to kill, hate and supports violence".[83]

Israeli Military Police

In a report published in February 2014 covering incidents over the three-year period of 2011–2013, Amnesty International asserted that Israeli forces employed reckless violence in the West Bank, and in some instances appeared to engage in wilful killings which would be tantamount to war crimes. Besides the numerous fatalities, Amnesty said at least 261 Palestinians, including 67 children, had been gravely injured by Israeli use of live ammunition. In this same period, 45 Palestinians, including 6 children had been killed. Amnesty's review of 25 civilians deaths concluded that in no case was there evidence of the Palestinians posing an imminent threat. At the same time, over 8,000 Palestinians suffered serious injuries from other means, including rubber-coated metal bullets. Only one IDF soldier was convicted, killing a Palestinian attempting to enter Israel illegally. The soldier was demoted and given a 1-year sentence with a five-month suspension. The IDF answered the charges stating that its army held itself "to the highest of professional standards," adding that when there was suspicion of wrongdoing, it investigated and took action "where appropriate".[84][85]

Incitement

Following the Oslo Accords, which was to set up regulative bodies to rein in frictions, Palestinian incitement against Israel, Jews, and Zionism continued, parallel with Israel's pursuance of settlements in the Palestinian territories,[86] though under Abu Mazen it has reportedly dwindled significantly.[87] Charges of incitement have been reciprocal,[88][89] both sides interpreting media statements in the Palestinian and Israeli press as constituting incitement.[87] In Israeli usage, the term also covers failures to mention Israel's culture and history in Palestinian textbooks.[90] Perpetrators of murderous attacks, whether against Israelis or Palestinians, often find strong vocal support from sections of their communities despite varying levels of condemnation from politicians.[91][92][93]

Both parties to the conflict have been criticized by third-parties for teaching incitement to their children by downplaying each side's historical ties to the area, teaching propagandist maps, or indoctrinate their children to one day join the armed forces.[94][95]

UN and the Palestinian state

The PLO have campaigned for full member status for the state of Palestine at the UN and for recognition on the 1967 borders. A campaign that has received widespread support,[96][97] though it has been criticised by the US and Israel for allegedly avoiding bilateral negotiation.[98][99] Netanyahu has criticized the Palestinians of purportedly trying to bypass direct talks,[100] whereas Abbas has argued that the continued construction of Israeli-Jewish settlements is "undermining the realistic potential" for the two-state solution.[101] Although Palestine has been denied full member status by the UN Security Council,[102] in late 2012 the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly approved the de facto recognition of sovereign Palestine by granting non-member state status.[103]

Public support

Polling data has produced mixed results regarding the level of support among Palestinians for the two-state solution. A poll was carried out in 2011 by the Hebrew University; it indicated that support for a two-state solution was growing among both Israelis and Palestinians. The poll found that 58% of Israelis and 50% of Palestinians supported a two-state solution based on the Clinton Parameters, compared with 47% of Israelis and 39% of Palestinians in 2003, the first year the poll was carried out. The poll also found that an increasing percentage of both populations supported an end to violence—63% of Palestinians and 70% of Israelis expressing their support for an end to violence, an increase of 2% for Israelis and 5% for Palestinians from the previous year.[104]

Issues in dispute

The following outlined positions are the official positions of the two parties; however, it is important to note that neither side holds a single position. Both the Israeli and the Palestinian sides include both moderate and extremist bodies as well as dovish and hawkish bodies.

One of the primary obstacles to resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is a deep-set and growing distrust between its participants. Unilateral strategies and the rhetoric of hardline political factions, coupled with violence and incitements by civilians against one another, have fostered mutual embitterment and hostility and a loss of faith in the peace process. Support among Palestinians for Hamas is considerable, and as its members consistently call for the destruction of Israel and violence remains a threat, security becomes a prime concern for many Israelis. The expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank has led the majority of Palestinians to believe that Israel is not committed to reaching an agreement, but rather to a pursuit of establishing permanent control over this territory in order to provide that security.[105]

Jerusalem

The control of Jerusalem is a particularly delicate issue, with each side asserting claims over the city. The three largest Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—hold Jerusalem as an important setting for their religious and historical narratives. Jerusalem is the holiest city for Judaism, being the former location of the Jewish temples on the Temple Mount and the capital of the ancient Israelite kingdom. For Muslims, Jerusalem is the third holiest site, being the location of Isra and Mi'raj event, and the Al-Aqsa mosque. For Christians, Jerusalem is the site of Jesus' crucifixion and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The Israeli government, including the Knesset and Supreme Court, is located in the "new city" of West Jerusalem and has been since Israel's founding in 1948. After Israel captured the Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem in the Six-Day War, it assumed complete administrative control of East Jerusalem. In 1980, Israel passed the Jerusalem Law declaring "Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel."[106]

Many countries do not recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital, with exceptions being the United States,[107] and Russia.[108] The majority of UN member states and most international organisations do not recognise Israel's claims to East Jerusalem which occurred after the 1967 Six-Day War, nor its 1980 Jerusalem Law proclamation.[109] The International Court of Justice in its 2004 Advisory opinion on the "Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory" described East Jerusalem as "occupied Palestinian territory."[110]

As of 2005, there were more than 719,000 people living in Jerusalem; 465,000 were Jews (mostly living in West Jerusalem) and 232,000 were Muslims (mostly living in East Jerusalem).[111]

At the Camp David and Taba Summits in 2000–2001, the United States proposed a plan in which the Arab parts of Jerusalem would be given to the proposed Palestinian state while the Jewish parts of Jerusalem were given to Israel. All archaeological work under the Temple Mount would be jointly controlled by the Israeli and Palestinian governments. Both sides accepted the proposal in principle, but the summits ultimately failed.[112]

Israel expresses concern over the security of its residents if neighborhoods of Jerusalem are placed under Palestinian control. Jerusalem has been a prime target for attacks by militant groups against civilian targets since 1967. Many Jewish neighborhoods have been fired upon from Arab areas. The proximity of the Arab areas, if these regions were to fall in the boundaries of a Palestinian state, would be so close as to threaten the safety of Jewish residents.[113]

Holy sites

Israel has concerns regarding the welfare of Jewish holy places under possible Palestinian control. When Jerusalem was under Jordanian control, no Jews were allowed to visit the Western Wall or other Jewish holy places, and the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives was desecrated.[112] Since 1975, Israel has banned Muslims from worshiping at Joseph's Tomb, a shrine considered sacred by both Jews and Muslims. Settlers established a yeshiva, installed a Torah scroll and covered the mihrab. During the Second Intifada the site was looted and burned.[114][115] Israeli security agencies routinely monitor and arrest Jewish extremists that plan attacks, though many serious incidents have still occurred.[116] Israel has allowed almost complete autonomy to the Muslim trust (Waqf) over the Temple Mount.[112]

Palestinians have voiced concerns regarding the welfare of Christian and Muslim holy places under Israeli control.[117] Additionally, some Palestinian advocates have made statements alleging that the Western Wall Tunnel was re-opened with the intent of causing the mosque's collapse.[118] The Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied this claim in a 1996 speech to the United Nations[119] and characterized the statement as "escalation of rhetoric."[120]

Palestinian refugees

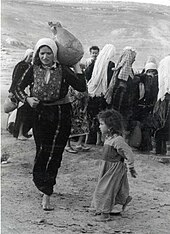

Palestinian refugees are people who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab–Israeli conflict[121] and the 1967 Six-Day War.[122] The number of Palestinians who fled or were expelled from Israel following its creation was estimated at 711,000 in 1949.[123] Descendants of these original Palestinian Refugees are also eligible for registration and services provided by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), and as of 2010 number 4.7 million people.[124] Between 350,000 and 400,000 Palestinians were displaced during the 1967 Arab–Israeli war.[122] A third of the refugees live in recognized refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The remainder live in and around the cities and towns of these host countries.[121]

Most of these people were born outside Israel, but are descendants of original Palestinian refugees.[121] Palestinian negotiators, such as Yasser Arafat,[125] have so far publicly insisted that refugees have a right to return to the places where they lived before 1948 and 1967, including those within the 1949 Armistice lines, citing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and UN General Assembly Resolution 194 as evidence. However, according to reports of private peace negotiations with Israel they have countenanced the return of only 10,000 refugees and their families to Israel as part of a peace settlement. Mahmoud Abbas, the current Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization was reported to have said in private discussion that it is "illogical to ask Israel to take 5 million, or indeed 1 million. That would mean the end of Israel."[126] In a further interview Abbas stated that he no longer had an automatic right to return to Safed in the northern Galilee where he was born in 1935. He later clarified that the remark was his personal opinion and not official policy.[127]

The Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 declared that it proposed the compromise of a "just resolution" of the refugee problem.[128]

Palestinian and international authors have justified the right of return of the Palestinian refugees on several grounds:[129][130][131]

- Several scholars included in the broader New Historians argue that the Palestinian refugees were chased out or expelled by the actions of the Haganah, Lehi and Irgun, Zionist paramilitary groups.[132][133] A number have also characterized this as an ethnic cleansing.[134][135][136][137] The New Historians cite indications of Arab leaders' desire for the Palestinian Arab population to stay put.[138]

Shlaim (2000) states that from April 1948 the military forces of what was to become Israel had embarked on a new offensive strategy which involved destroying Arab villages and the forced removal of civilians.

- The Israeli Law of Return that grants citizenship to any Jew from anywhere in the world is viewed by some as discrimination against non-Jews, especially Palestinians that cannot apply for such citizenship or return to the territory which they were expelled from or fled during the course of the 1948 war.[139][140][141]

- According to the UN Resolution 194, adopted in 1948, "the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible."[142] UN Resolution 3236 "reaffirms also the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and calls for their return".[143] Resolution 242 from the UN affirms the necessity for "achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem"; however, Resolution 242 does not specify that the "just settlement" must or should be in the form of a literal Palestinian right of return.[144]

The most common arguments for opposition are:

- The Israeli government asserts that the Arab refugee problem is largely caused by the refusal of all Arab governments except Jordan to grant citizenship to Palestinian Arabs who reside within those countries' borders. This has produced much of the poverty and economic problems of the refugees, according to MFA documents.[145]

- The Palestinian refugee issue is handled by a separate authority from that handling other refugees, that is, by UNRWA and not the UNHCR. Most of the people recognizing themselves as Palestinian refugees would have otherwise been assimilated into their country of current residency, and would not maintain their refugee state if not for the separate entities.[146]

- Concerning the origin of the Palestinian refugees, the official version of the Israeli government is that during the 1948 War the Arab Higher Committee and the Arab states encouraged Palestinians to flee in order to make it easier to rout the Jewish state or that they did so to escape the fights by fear.[145] The Palestinian narrative is that refugees were expelled and dispossessed by Jewish militias and by the Israeli army, following a plan established even before the war.[citation needed] Historians still debate the causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus.

- Since none of the 900,000 Jewish refugees who fled anti-Semitic violence in the Arab world was ever compensated or repatriated by their former countries of residence—to no objection on the part of Arab leaders—a precedent has been set whereby it is the responsibility of the nation which accepts the refugees to assimilate them.[147][148][149]

- Although Israel accepts the right of the Palestinian Diaspora to return into a new Palestinian state, Israel insists that their return into the current state of Israel would be a great danger for the stability of the Jewish state; an influx of Palestinian refugees would lead to the destruction of the state of Israel.[150][151]

- Historian Benny Morris states that most of Palestine's 700,000 refugees fled because of the "flail of war" and expected to return home shortly after a successful Arab invasion. He documents instances in which Arab leaders advised the evacuation of entire communities as happened in Haifa. In his scholarly work, however, he does conclude that there were expulsions which were carried out.[152][153] Morris considers the displacement the result of a national conflict initiated by the Arabs themselves.[153] In a 2004 interview with Haaretz, he described the exodus as largely resulting from an atmosphere of transfer that was promoted by Ben-Gurion and understood by the military leadership. He also claimed that there "are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing".[154] He has been criticized by political scientist Norman Finkelstein for having seemingly changed his views for political, rather than historical, reasons.[155]

- According to Karsh the Palestinians were themselves the aggressors in the 1948–1949 war who attempted to "cleanse" a neighboring ethnic community. Had the United Nations resolution of 29 November 1947 recommending partition in Palestine not been subverted by force by the Arab world, there would have been no refugee problem in the first place. He reports of large numbers of Palestinian refugees leaving even before the outbreak of the 1948 war because of disillusionment and economic privation. The British High Commissioner for Palestine spoke of the "collapsing Arab morale in Palestine" that he partially attributed to the "increasing tendency of those who should be leading them to leave the country" and the considerable evacuations of the Arab effendi class. Huge numbers of Palestinians were also expelled by their leadership to prevent them from becoming Israeli citizens and in Haifa and Tiberias, tens of thousands of Arabs were forcibly evacuated on the instructions of the Arab Higher Committee.[156]

Israeli security concerns

Throughout the conflict, Palestinian violence has been a concern for Israelis. Israel,[157] along with the United States[158] and the European Union, refer to the violence against Israeli civilians and military forces by Palestinian militants as terrorism. The motivations behind Palestinian violence against Israeli civilians are many, and not all violent Palestinian groups agree with each other on specifics. Nonetheless, a common motive is the desire to destroy Israel and replace it with a Palestinian Arab state.[159] The most prominent Islamist groups, such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, view the Israeli–Palestinian conflict as a religious jihad.[160]

Suicide bombing have been used as a tactic among Palestinian organizations like Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade and certain suicide attacks have received support among Palestinians as high as 84%.[161][162] In Israel, Palestinian suicide bombers have targeted civilian buses, restaurants, shopping malls, hotels and marketplaces.[163] From 1993 to 2003, 303 Palestinian suicide bombers attacked Israel.

The Israeli government initiated the construction of a security barrier following scores of suicide bombings and terrorist attacks in July 2003. Israel's coalition government approved the security barrier in the northern part of the green line between Israel and the West Bank. According to the IDF, since the erection of the fence, terrorist acts have declined by approximately 90%.[164]

Since 2001, the threat of Qassam rockets fired from Palestinian territories into Israel continues to be of great concern for Israeli defense officials.[165] In 2006—the year following Israel's disengagement from the Gaza Strip—the Israeli government recorded 1,726 such launches, more than four times the total rockets fired in 2005.[157] As of January 2009, over 8,600 rockets have been launched,[166][167] causing widespread psychological trauma and disruption of daily life.[168] Over 500 rockets and mortars hit Israel in January–September 2010 and over 1,947 rockets hit Israel in January–November 2012.

According to a study conducted by University of Haifa, one in five Israelis have lost a relative or friend in a Palestinian terrorist attack.[169]

There is significant debate within Israel about how to deal with the country's security concerns. Options have included military action (including targeted killings and house demolitions of terrorist operatives), diplomacy, unilateral gestures toward peace, and increased security measures such as checkpoints, roadblocks and security barriers. The legality and the wisdom of all of the above tactics have been called into question by various commentators.[20][unreliable source?]

Since mid-June 2007, Israel's primary means of dealing with security concerns in the West Bank has been to cooperate with and permit United States-sponsored training, equipping, and funding of the Palestinian Authority's security forces, which with Israeli help have largely succeeded in quelling West Bank supporters of Hamas.[170]

Palestinian violence outside Israel

Some Palestinians have committed violent acts over the globe on the pretext of a struggle against Israel. Many foreigners, including Americans[171] and Europeans,[172] have been killed and injured by Palestinian militants. At least 53 Americans have been killed and 83 injured by Palestinian violence since the signing of the Oslo Accords.[173][unreliable source?]

During the late 1960s, the PLO became increasingly infamous for its use of international terror. In 1969 alone, the PLO was responsible for hijacking 82 planes. El Al Airlines became a regular hijacking target.[174][175] The hijacking of Air France Flight 139 by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine culminated during a hostage-rescue mission, where Israeli special forces successfully rescued the majority of the hostages.

However, one of the most well-known and notorious terrorist acts was the capture and eventual murder of 11 Israeli athletes during the 1972 Olympic Games.[176]

Palestinian violence against other Palestinians

Fighting among rival Palestinian and Arab movements has played a crucial role in shaping Israel's security policy towards Palestinian militants, as well as in the Palestinian leadership's own policies.[citation needed] As early as the 1930s revolts in Palestine, Arab forces fought each other while also skirmishing with Zionist and British forces, and internal conflicts continue to the present day. During the Lebanese Civil War, Palestinian baathists broke from the Palestine Liberation Organization and allied with the Shia Amal Movement, fighting a bloody civil war that killed thousands of Palestinians.[177][178]

In the First Intifada, more than a thousand Palestinians were killed in a campaign initiated by the Palestine Liberation Organization to crack down on suspected Israeli security service informers and collaborators. The Palestinian Authority was strongly criticized for its treatment of alleged collaborators, rights groups complaining that those labeled collaborators were denied fair trials. According to a report released by the Palestinian Human Rights Monitoring Group, less than 45 percent of those killed were actually guilty of informing for Israel.[179]

The policies towards suspected collaborators contravene agreements signed by the Palestinian leadership. Article XVI(2) of the Oslo II Agreement states:[180]

"Palestinians who have maintained contact with the Israeli authorities will not be subjected to acts of harassment, violence, retribution, or prosecution."

The provision was designed to prevent Palestinian leaders from imposing retribution on fellow Palestinians who had worked on behalf of Israel during the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

In the Gaza Strip, Hamas officials have tortured and killed thousands of Fatah members and other Palestinians who oppose their rule. During the Battle of Gaza, more than 150 Palestinians died over a four-day period.[181] The violence among Palestinians was described as a civil war by some commentators. By 2007, more than 600 Palestinian people had died during the struggle between Hamas and Fatah.[182]

International status

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2018) |

As far as Israel is concerned, the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority is derived from the Oslo Accords, signed with the PLO, under which it acquired control over cities in the Palestinian territories (Area A) while the surrounding countryside came either under Israeli security and Palestinian civil administration (Area B) or complete Israeli civil administration (Area C). Israel has built additional highways to allow Israelis to traverse the area without entering Palestinian cities in Area A. The initial areas under Palestinian Authority control are diverse and non-contiguous. The areas have changed over time by subsequent negotiations, including Oslo II, Wye River and Sharm el-Sheik. According to Palestinians, the separated areas make it impossible to create a viable nation and fails to address Palestinian security needs; Israel has expressed no agreement to withdrawal from some Areas B, resulting in no reduction in the division of the Palestinian areas, and the institution of a safe pass system, without Israeli checkpoints, between these parts.

Under the Oslo Accords, as a security measure, Israel has insisted on its control over all land, sea and air border crossings into the Palestinian territories, and the right to set import and export controls. This is to enable Israel to control the entry into the territories of materials of military significance and of potentially dangerous persons.

The PLO's objective for international recognition of the State of Palestine is considered by Israel as a provocative "unilateral" act that is inconsistent with the Oslo Accords.

Water resources

In the Middle East, water resources are of great political concern. Since Israel receives much of its water from two large underground aquifers which continue under the Green Line, the use of this water has been contentious in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Israel withdraws most water from these areas, but it also supplies the West Bank with approximately 40 million cubic metres annually, contributing to 77% of Palestinians' water supply in the West Bank, which is to be shared for a population of about 2.6 million.[183]

While Israel's consumption of this water has decreased since it began its occupation of the West Bank, it still consumes the majority of it: in the 1950s, Israel consumed 95% of the water output of the Western Aquifer, and 82% of that produced by the Northeastern Aquifer. Although this water was drawn entirely on Israel's own side of the pre-1967 border, the sources of the water are nevertheless from the shared groundwater basins located under both West Bank and Israel.[184]

In the Oslo II Accord, both sides agreed to maintain "existing quantities of utilization from the resources." In so doing, the Palestinian Authority established the legality of Israeli water production in the West Bank, subject to a Joint Water Committee (JWC). Moreover, Israel obligated itself in this agreement to provide water to supplement Palestinian production, and further agreed to allow additional Palestinian drilling in the Eastern Aquifer, also subject to the Joint Water Committee.[185] Many Palestinians counter that the Oslo II agreement was intended to be a temporary resolution and that it was not intended to remain in effect more than a decade later.

In 1999, Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs said it continued to honor its obligations under the Interim Agreement.[186] The water that Israel receives comes mainly from the Jordan River system, the Sea of Galilee and two underground sources. According to a 2003 BBC article the Palestinians lack access to the Jordan River system.[187]

According to a report of 2008 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, water resources were confiscated for the benefit of the Israeli settlements in the Ghor. Palestinian irrigation pumps on the Jordan River were destroyed or confiscated after the 1967 war and Palestinians were not allowed to use water from the Jordan River system. Furthermore, the authorities did not allow any new irrigation wells to be drilled by Palestinian farmers, while it provided fresh water and allowed drilling wells for irrigation purposes at the Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[188]

A report was released by the UN in August 2012 and Max Gaylard, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in the occupied Palestinian territory, explained at the launch of the publication: "Gaza will have half a million more people by 2020 while its economy will grow only slowly. In consequence, the people of Gaza will have an even harder time getting enough drinking water and electricity, or sending their children to school". Gaylard present alongside Jean Gough, of the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF), and Robert Turner, of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The report projects that Gaza's population will increase from 1.6 million people to 2.1 million people in 2020, leading to a density of more than 5,800 people per square kilometre.[189]

Future and financing

Numerous foreign nations and international organizations have established bilateral agreements with the Palestinian and Israeli water authorities. It is estimated that a future investment of about US$1.1bn for the West Bank and $0.8bn[clarification needed] is needed for the planning period from 2003 to 2015.[190]

In order to support and improve the water sector in the Palestinian territories, a number of bilateral and multilateral agencies have been supporting many different water and sanitation programs.

There are three large seawater desalination plants in Israel and two more scheduled to open before 2014. When the fourth plant becomes operational, 65% of Israel's water will come from desalination plants, according to Minister of Finance Dr. Yuval Steinitz.[191]

In late 2012, a donation of $21.6 million was announced by the Government of the Netherlands—the Dutch government stated that the funds would be provided to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), for the specific benefit of Palestinian children. An article, published by the UN News website, stated that: "Of the $21.6 million, $5.7 will be allocated to UNRWA's 2012 Emergency Appeal for the occupied Palestinian territory, which will support programmes in the West Bank and Gaza aiming to mitigate the effects on refugees of the deteriorating situation they face."[189]

Israeli military occupation of the West Bank

Occupied Palestinian Territory is the term used by the United Nations to refer to the West Bank, including East Jerusalem,[192] and the Gaza Strip—territories which were captured by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War, having formerly been controlled by Egypt and Jordan.[193] The Israeli government uses the term Disputed Territories, to argue that some territories cannot be called occupied as no nation had clear rights to them and there was no operative diplomatic arrangement when Israel acquired them in June 1967.[194][195] The area is still referred to as Judea and Samaria, based on the historical regional names from ancient times. This is also the name used on the 1947 UN Partition Plan.[196]

In 1980, Israel annexed East Jerusalem.[197] Israel has never annexed the West Bank, apart from East Jerusalem, or Gaza Strip, and the United Nations has demanded the "[t]ermination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgment of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force" and that Israeli forces withdraw "from territories occupied in the recent conflict" – the meaning and intent of the latter phrase is disputed. See Interpretations.

It has been the position of Israel that the most Arab-populated parts of West Bank (without major Jewish settlements), as well as the entire Gaza Strip, must eventually be part of an independent Palestinian State; however, the precise borders of this state are in question. At Camp David, for example, then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak offered Arafat an opportunity to establish a non-militarized Palestinian State. The proposed state would consist of 77% of the West Bank split into two or three areas, followed by: an increase of 86–91% of the West Bank after six to twenty-one years; autonomy, but not sovereignty for some of the Arab neighborhoods of East Jerusalem surrounded by Israeli territory; the entire Gaza Strip; and the dismantling of most settlements.[53] Arafat rejected the proposal without providing a counter-offer.

A subsequent settlement proposed by President Clinton offered Palestinian sovereignty over 94 to 96 percent of the West Bank but was similarly rejected with 52 objections.[52][198][199][200][201] The Arab League has agreed to the principle of minor and mutually agreed land-swaps as part of a negotiated two state settlement based in June 1967 borders.[202] Official U.S. policy also reflects the ideal of using the 1967 borders as a basis for an eventual peace agreement.[203][204]

Some Palestinians claim they are entitled to all of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. Israel says it is justified in not ceding all this land, because of security concerns, and also because the lack of any valid diplomatic agreement at the time means that ownership and boundaries of this land is open for discussion.[125] Palestinians claim any reduction of this claim is a severe deprivation of their rights. In negotiations, they claim that any moves to reduce the boundaries of this land is a hostile move against their key interests. Israel considers this land to be in dispute and feels the purpose of negotiations is to define what the final borders will be. Other Palestinian groups, such as Hamas, have in the past insisted that Palestinians must control not only the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem, but also all of Israel proper. For this reason, Hamas has viewed the peace process "as religiously forbidden and politically inconceivable".[160]

Israeli settlements in the West Bank

According to the Arizona Department of Emergency and Military Affairs (DEMA), "In the years following the Six-Day War, and especially in the 1990s during the peace process, Israel re-established communities destroyed in 1929 and 1948 as well as established numerous new settlements in the West Bank."[205] These settlements are, as of 2009, home to about 301,000 people.[206] DEMA added, "Most of the settlements are in the western parts of the West Bank, while others are deep into Palestinian territory, overlooking Palestinian cities. These settlements have been the site of much inter-communal conflict."[205] The issue of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and, until 2005, the Gaza Strip, have been described by the UK[207] and the WEU[208] as an obstacle to the peace process. The United Nations and the European Union have also called the settlements "illegal under international law."[209][210]

However, Israel disputes this;[211] several scholars and commentators disagree with the assessment that settlements are illegal, citing in 2005 recent historical trends to back up their argument.[212][213] Those who justify the legality of the settlements use arguments based upon Articles 2 and 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, as well as UN Security Council Resolution 242.[214] On a practical level, some objections voiced by Palestinians are that settlements divert resources needed by Palestinian towns, such as arable land, water, and other resources; and, that settlements reduce Palestinians' ability to travel freely via local roads, owing to security considerations.

In 2005, Israel's unilateral disengagement plan, a proposal put forward by Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, was enacted. All residents of Jewish settlements in the Gaza strip were evacuated, and all residential buildings were demolished.[215]

Various mediators and various proposed agreements have shown some degree of openness to Israel retaining some fraction of the settlements which currently exist in the West Bank; this openness is based on a variety of considerations, such as, the desire to find real compromise between Israeli and Palestinian territorial claims.[216][217]

Israel's position that it needs to retain some West Bank land and settlements as a buffer in case of future aggression,[218] and Israel's position that some settlements are legitimate, as they took shape when there was no operative diplomatic arrangement, and thus they did not violate any agreement.[194][195]

Former US President George W. Bush has stated that he does not expect Israel to return entirely to the 1949 armistice lines because of "new realities on the ground."[219] One of the main compromise plans put forth by the Clinton Administration would have allowed Israel to keep some settlements in the West Bank, especially those which were in large blocs near the pre-1967 borders of Israel. In return, Palestinians would have received some concessions of land in other parts of the country.[216] The Obama administration viewed a complete freeze of construction in settlements on the West Bank as a critical step toward peace. In May and June 2009, President Barack Obama said, "The United States does not accept the legitimacy of continued Israeli settlements,"[220] and the Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, stated that the President "wants to see a stop to settlements—not some settlements, not outposts, not 'natural growth' exceptions."[221] However, Obama has since declared that the United States will no longer press Israel to stop West Bank settlement construction as a precondition for continued peace-process negotiations with the Palestinian Authority.[222]

Gaza blockade

The Israeli government states it is justified under international law to impose a blockade on an enemy for security reasons. The power to impose a naval blockade is established under customary international law and Laws of armed conflict, and a United Nations commission has ruled that Israel's blockade is "both legal and appropriate."[223][224] The Israeli Government's continued land, sea and air blockage is tantamount to collective punishment of the population, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.[225] The Military Advocate General of Israel has provided numerous reasonings for the policy:

"The State of Israel has been engaged in an ongoing armed conflict with terrorist organizations operating in the Gaza strip. This armed conflict has intensified after Hamas violently took over Gaza, in June 2007, and turned the territory under its de facto control into a launching pad of mortar and rocket attacks against Israeli towns and villages in southern Israel."[226]

According to Oxfam, because of an import-export ban imposed on Gaza in 2007, 95% of Gaza's industrial operations were suspended. Out of 35,000 people employed by 3,900 factories in June 2005, only 1,750 people remained employed by 195 factories in June 2007.[227] By 2010, Gaza's unemployment rate had risen to 40% with 80% of the population living on less than 2 dollars a day.[228]

In January 2008, the Israeli government calculated how many calories per person were needed to prevent a humanitarian crisis in the Gaza strip, and then subtracted eight percent to adjust for the "culture and experience" of the Gazans. Details of the calculations were released following Israeli human rights organization Gisha's application to the high court. Israel's Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, who drafted the plan, stated that the scheme was never formally adopted, this was not accepted by Gisha.[229][230][231]

Starting 7 February 2008, the Israeli Government reduced the electricity it sells directly to Gaza. This follows the ruling of Israel's High Court of Justice's decision, which held, with respect to the amount of industrial fuel supplied to Gaza, that, "The clarification that we made indicates that the supply of industrial diesel fuel to the Gaza Strip in the winter months of last year was comparable to the amount that the Respondents now undertake to allow into the Gaza Strip. This fact also indicates that the amount is reasonable and sufficient to meet the vital humanitarian needs in the Gaza Strip." Palestinian militants killed two Israelis in the process of delivering fuel to the Nahal Oz fuel depot.[232]

With regard to Israel's plan, the Court stated that, "calls for a reduction of five percent of the power supply in three of the ten power lines that supply electricity from Israel to the Gaza Strip, to a level of 13.5 megawatts in two of the lines and 12.5 megawatts in the third line, we [the Court] were convinced that this reduction does not breach the humanitarian obligations imposed on the State of Israel in the framework of the armed conflict being waged between it and the Hamas organization that controls the Gaza Strip. Our conclusion is based, in part, on the affidavit of the Respondents indicating that the relevant Palestinian officials stated that they can reduce the load in the event limitations are placed on the power lines, and that they had used this capability in the past."

On 20 June 2010, Israel's Security Cabinet approved a new system governing the blockade that would allow practically all non-military or dual-use items to enter the Gaza strip. According to a cabinet statement, Israel would "expand the transfer of construction materials designated for projects that have been approved by the Palestinian Authority, including schools, health institutions, water, sanitation and more – as well as (projects) that are under international supervision."[233] Despite the easing of the land blockade, Israel will continue to inspect all goods bound for Gaza by sea at the port of Ashdod.[234]

Prior to a Gaza visit, scheduled for April 2013, Turkey's Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan explained to Turkish newspaper Hürriyet that the fulfilment of three conditions by Israel was necessary for friendly relations to resume between Turkey and Israel: an apology for the May 2010 Gaza flotilla raid (Prime Minister Netanyahu had delivered an apology to Erdogan by telephone on 22 March 2013), the awarding of compensation to the families affected by the raid, and the lifting of the Gaza blockade by Israel. The Turkish prime minister also explained in the Hürriyet interview, in relation to the April 2013 Gaza visit, "We will monitor the situation to see if the promises are kept or not."[235] At the same time, Netanyahu affirmed that Israel would only consider exploring the removal of the Gaza blockade if peace ("quiet") is achieved in the area.[236]

Agriculture

Since the beginning of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the conflict has been about land.[237] When Israel became a state after the war in 1948, 77% of Palestine's land was used for the creation on the state.[citation needed] The majority of those living in Palestine at the time became refugees in other countries and this first land crisis became the root of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[238] Because the root of the conflict is with land, the disputes between Israel and Palestine are well-manifested in the agriculture of Palestine.

In Palestine, agriculture is a mainstay in the economy. The production of agricultural goods supports the population's sustenance needs and fuels Palestine's export economy.[239] According to the Council for European Palestinian Relations, the agricultural sector formally employs 13.4% of the population and informally employs 90% of the population.[239] Over the past 10 years, unemployment rates in Palestine have increased and the agricultural sector became the most impoverished sector in Palestine. Unemployment rates peaked in 2008 when they reached 41% in Gaza.[240]

Palestinian agriculture suffers from numerous problems including Israeli military and civilian attacks on farms and farmers, blockades to exportation of produce and importation of necessary inputs, widespread confiscation of land for nature reserves as well as military and settler use, confiscation and destruction of wells, and physical barriers within the West Bank.[241]

The West Bank barrier

With the construction of the separation barrier, the Israeli state promised free movement across regions. However, border closures, curfews, and checkpoints has significantly restricted Palestinian movement.[242] In 2012, there were 99 fixed check points and 310 flying checkpoints.[243] The border restrictions impacted the imports and exports in Palestine and weakened the industrial and agricultural sectors because of the constant Israeli control in the West Bank and Gaza.[244] In order for the Palestinian economy to be prosperous, the restrictions on Palestinian land must be removed.[241] According to The Guardian and a report for World Bank, the Palestinian economy lost $3.4bn (%35 of the annual GDP) to Israeli restrictions in the West Bank alone.[245]

Boycotts

In Gaza, the agricultural market suffers from economic boycotts and border closures and restrictions placed by Israel.[citation needed] The PA's Minister of Agriculture estimates that around US$1.2 billion were lost in September 2006 because of these security measures. There has also been an economic embargo initiated by the west on Hamas-led Palestine, which has decreased the amount of imports and exports from Palestine.[citation needed] This embargo was brought on by Hamas' refusal to recognize Israel's right to statehood. As a result, the PA's 160,000 employees have not received their salaries in over one year.[246]

Actions toward stabilizing the conflict

In response to a weakening trend in Palestinian violence and growing economic and security cooperation between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, the Israeli military has removed over 120 check points in 2010 and plans on disengaging from major Palestinian population areas. According to the IDF, terrorist activity in the West Bank decreased by 97% compared to violence in 2002.[247]

PA–Israel efforts in the West Bank have "significantly increased investor confidence", and the Palestinian economy grew 6.8% in 2009.[248][249][250][251][252]

Since the Second Intifada, Israel has banned Jewish Israelis from entering Palestinian cities. However, Israeli Arabs are allowed to enter West Bank cities on weekends.

The Palestinian Authority has petitioned the Israeli military to allow Jewish tourists to visit West Bank cities as "part of an effort" to improve the Palestinian economy. Israeli general Avi Mizrahi spoke with Palestinian security officers while touring malls and soccer fields in the West Bank. Mizrahi gave permission to allow Israeli tour guides into Bethlehem, a move intended to "contribute to the Palestinian and Israeli economies."[253]

Mutual recognition

Beginning in 1993 with the Oslo peace process, Israel recognizes "the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people", though Israel does not recognize the State of Palestine.[254] In return, it was agreed that Palestinians would promote peaceful co-existence, renounce violence and promote recognition of Israel among their own people. Despite Yasser Arafat's official renunciation of terrorism and recognition of Israel, some Palestinian groups continue to practice and advocate violence against civilians and do not recognize Israel as a legitimate political entity.[25][255][unreliable source?] Palestinians state that their ability to spread acceptance of Israel was greatly hampered by Israeli restrictions on Palestinian political freedoms, economic freedoms, civil liberties, and quality of life.

It is widely felt among Israelis that Palestinians did not in fact promote acceptance of Israel's right to exist.[256][257] One of Israel's major reservations in regards to recognizing Palestinian sovereignty is its concern that there is not genuine public support by Palestinians for co-existence and elimination of militantism and incitement.[256][257][258] Some Palestinian groups, including Fatah, the political party founded by PLO leaders, state they are willing to foster co-existence depending on the Palestinians being steadily given more political rights and autonomy.

President of Palestine, Mahmoud Abbas has in recent years refused to recognize Israel as a Jewish state citing concerns for Israeli Arabs and a possible future right to return for Palestinian refugees, though Palestine continues to recognize Israel as a state.[259][260] The leader of al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, which is Fatah's official military wing, has stated that any peace agreement must include the right of return of Palestinian refugees into lands now part of Israel, which some Israeli commenters view as "destroying the Jewish state".[261] In 2006, Hamas won a majority in the Palestinian Legislative Council, where it remains the majority party. Hamas' charter openly states they seek Israel's destruction, though Hamas leaders have spoken of long-term truces with Israel in exchange for an end to the occupation of Palestinian territory.[255][262]

Government

The Palestinian Authority is considered corrupt by a wide variety of sources, including some Palestinians.[263][264][265] Some Israelis argue that it provides tacit support for militants via its relationship with Hamas and other Islamic militant movements, and that therefore it is unsuitable for governing any putative Palestinian state or (especially according to the right wing of Israeli politics), even negotiating about the character of such a state.[125] Because of that, a number of organizations, including the previously ruling Likud party, declared they would not accept a Palestinian state based on the current PA.

Societal attitudes

Societal attitudes in both Israel and Palestine are a source of concern to those promoting dispute resolution.

According to a May 2011 poll carried out by the Palestinian Center For Public Opinion that asked Palestinians from the Gaza Strip and the West Bank including East Jerusalem, "which of the following means is the best to end the occupation and lead to the establishment of an independent Palestinian state", 5.0% supported "military operations", 25.0% supported non-violent popular resistance, 32.1% favored negotiations until an agreement could be reached, 23.1% preferred holding an international conference that would impose a solution on all parties, 12.4% supported seeking a solution through the United Nations, and 2.4% otherwise. Approximately three-quarters of Palestinians surveyed believed that a military escalation in the Gaza Strip would be in Israel's interest and 18.9% said it would be in Hamas's interest. Regarding the resumption of launching Al-Qassam missiles from Gaza into Israel, 42.5% said "strongly oppose", 27.1% "somewhat oppose", 16.0% "somewhat support", 13.8% "strongly support", and 0.2% expressed no opinion.[266]