Kendrick Lamar

Kendrick Lamar | |

|---|---|

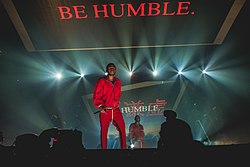

Duckworth in May 2018 | |

| Born | Kendrick Lamar Duckworth June 17, 1987 Compton, California, U.S. |

| Other names | K.Dot |

| Education | Centennial High School |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 2004–present |

| Agent | Dave Free |

| Title | Co-founder of pgLang |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | kendricklamar |

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth (born June 17, 1987) is an American rapper, songwriter, and record producer. Since his mainstream debut in 2012 with Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, Lamar has been regarded as one of the most influential rappers of his generation.[1][2][3] Aside from his solo career, he is also known as a member of the hip hop supergroup Black Hippy alongside his Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE) label-mates Ab-Soul, Jay Rock, and Schoolboy Q.

Raised in Compton, California, Lamar embarked on his musical career as a teenager under the stage name K.Dot, releasing a mixtape that garnered local attention and led to his signing with indie record label Top Dawg Entertainment. He began to gain recognition in 2010 after his first retail release, Overly Dedicated. The following year, he independently released his first studio album, Section.80, which included his debut single "HiiiPoWeR". By that time, he had amassed a large online following and collaborated with several prominent hip hop artists.

Lamar's major label debut album, Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, was released in 2012 to critical acclaim. It was later certified Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). His third album To Pimp a Butterfly (2015) incorporated elements of funk, soul, jazz, and spoken word. It became his first number one album on the Billboard 200, and was the most acclaimed album of the 2010s, according to statistics from Metacritic.[4] It was followed by Untitled Unmastered (2016), a collection of unreleased demos that originated during the recording sessions for To Pimp a Butterfly. He released his fourth album, Damn (2017) to further acclaim; its lead single "Humble" topped the US Billboard Hot 100, while the album became the first non-classical and non-jazz album to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music.[5] In 2018, he wrote and produced 14 songs for the soundtrack to the superhero film Black Panther, which also received critical acclaim.

Lamar has received many accolades over the course of his career, including 13 Grammy Awards, two American Music Awards, five Billboard Music Awards, a Brit Award, 11 MTV Video Music Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, and an Academy Award nomination. In 2012, MTV named him the Hottest MC in the Game on their annual list.[6] Time named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2016.[7] In 2015, he received the California State Senate's Generational Icon Award. Three of his studio albums have been listed in Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (2020).

Early life

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth was born in Compton, California, on June 17, 1987,[8][9] the son of a couple from Chicago.[10] Although not in a gang himself, he grew up around gang members, with his closest friends being Westside Piru Bloods and his father, Kenny Duckworth, being a Gangster Disciple.[11][12] His first name was given to him by his mother in honor of American singer-songwriter Eddie Kendricks of The Temptations.[13] He grew up on welfare and in Section 8 housing. In 1995, at the age of eight, Lamar witnessed his idols Tupac Shakur and Dr. Dre filming the music video for their hit single "California Love", which proved to be a significant moment in his life.[14] As a child, Lamar attended McNair Elementary and Vanguard Learning Center in the Compton Unified School District. He has admitted to being quiet and shy in school, his mother even confirming he was a "loner" until the age of seven.[15][11] As a teenager, he attended Centennial High School in Compton, where he was a straight-A student.[10][16][17]

Career

2004–2009: Career beginnings

In 2004, at the age of 16, Lamar released his first full-length project, a mixtape titled Youngest Head Nigga in Charge (Hub City Threat: Minor of the Year), under the pseudonym K.Dot.[18] The mixtape was released under Konkrete Jungle Muzik and garnered local recognition for Lamar.[19] The mixtape led to Lamar securing a recording contract with Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE), a newly founded indie record label based in Carson, California.[18] He began recording material with the label and subsequently released a 26-track mixtape two years later, titled Training Day (2005).[20]

Throughout 2006 and 2007, Lamar would appear alongside other up-and-coming West Coast rappers, such as Jay Rock and Ya Boy, as opening acts for veteran West Coast rapper The Game. Under the moniker K.Dot, Lamar was also featured on The Game's songs "The Cypha" and "Cali Niggaz".[21][22]

In 2008, Lamar was prominently featured throughout the music video for Jay Rock's commercial debut single, "All My Life (In the Ghetto)", which features American hip hop superstar Lil Wayne and was backed by Warner Bros. Records. Lamar garnered further recognition after a video of a live performance of a Charles Hamilton show surfaced, in which Hamilton battled fellow rappers who were in the audience. Lamar began rapping a verse over the instrumental to Miilkbone's "Keep It Real", which would later appear on a track titled "West Coast Wu-Tang".[14]

After receiving a co-sign from Lil Wayne,[23][24] Lamar released his third mixtape in 2009, titled C4, which was heavily themed around Wayne's album Tha Carter III.[25] Soon after, Lamar decided to no longer go by the stage name of K.Dot and opted to use his birth name. He subsequently released a self-titled extended play in late 2009.[26] That same year, Lamar along with his TDE label-mates: Jay Rock, Ab-Soul and ScHoolboy Q formed Black Hippy, a hip hop supergroup.[27]

2010–2011: Overly Dedicated and Section.80

Throughout 2010, Lamar toured with Tech N9ne and Jay Rock on The Independent Grind tour.[18] On September 14, 2010, he released the visuals for "P&P 1.5", a song taken from his mixtape, Overly Dedicated, featuring his Black Hippy cohort Ab-Soul.[28] On the same date, Lamar released Overly Dedicated to digital retailers under Top Dawg Entertainment, and later on September 23, released it for free online.[29][30] The project fared well enough to enter the United States Billboard Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart, where it peaked at number 72.[31]

The mixtape includes a song titled "Ignorance Is Bliss", in which Lamar highlights gangsta rap and street crime, but ends each verse with "ignorance is bliss", giving the message "we know not what we do;"[32][33] it was this song specifically that made hip hop producer Dr. Dre want to work with Lamar after seeing the music video on YouTube.[34] This led to Lamar working with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg on Dre's often-delayed Detox album, as well as speculation of Lamar signing to Dr. Dre's record label, Aftermath Entertainment.[18][35][36] In December 2010, Complex magazine spotlighted Lamar in an edition of their "Indie Intro" series.[37]

In early 2011, Lamar was included in XXL's annual Top 10 Freshman Class, and was featured on the cover alongside fellow up-and-coming rappers Cyhi the Prynce, Meek Mill, Fred the Godson, Mac Miller, Yelawolf and Big K.R.I.T., and Diggy Simmons.[38] On April 11, 2011, Lamar announced the title of his next full-length project to be Section.80,[39] and the following day the first single "HiiiPoWeR" was released, the concept of which was to further explain the HiiiPoWeR movement.[40] The song was produced by fellow American rapper J. Cole, marking their first of several collaborations.[40]

On the topic of whether his next project would be an album or a mixtape, Lamar answered: "I treat every project like it's an album anyway. It's not going to be nothing leftover. I never do nothing like that. These are my leftover songs you all can have them. I'm going to put my best out. My best effort. I'm trying to look for an album in 2012."[41] In June 2011, Lamar released "Ronald Reagan Era (His Evils)", a cut from Section.80, featuring Wu-Tang Clan leader RZA.[42] On July 2, 2011, Lamar released Section.80, his first independent album, to critical acclaim. The album features guest appearances from GLC, Colin Munroe, Schoolboy Q, and Ab-Soul, while the production was handled by Top Dawg in-house production team Digi+Phonics as well as Wyldfyer, Terrace Martin and J. Cole. Section.80 went on to sell 5,300 digital copies in its first week, without any television or radio coverage, and received mostly positive reviews.[43]

In August 2011, while performing at a West Los Angeles concert, Lamar was dubbed the "New King of the West Coast" by Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre and Game.[44][45] On August 24, 2011, Lamar released the music video for the Section.80 track, "ADHD". The video was directed by Vashtie Kola who had this to say of the video: "Inspired by "A.D.H.D"'s dark beat and melancholy lyrics which explore a generation in conflict, we find Kendrick Lamar in a video that illustrates the songs[sic] universal and age-old theme of apathetic youth. (...) Shot in New York City during the sweltering July Summer heat".[46] In October 2011, Lamar appeared alongside fellow American rappers B.o.B, Tech N9ne, MGK, and Big K.R.I.T., in a cypher at the BET Hip Hop Awards.[47] Also in October, Lamar partnered with Windows Phone, and crafted an original song with producer Nosaj Thing entitled "Cloud 10", to promote Microsoft's new product.[48] During 2011, Lamar appeared on several high-profile albums including Game's The R.E.D. Album, Tech N9ne's All 6's and 7's, 9th Wonder's The Wonder Years and Canadian recording artist Drake's Grammy Award-winning Take Care, which featured Lamar on a solo track.[49]

2012–2013: Good Kid, M.A.A.D City and controversies

On February 15, 2012, a song by Lamar titled "Cartoon and Cereal", featuring fellow American rapper Gunplay, was leaked online.[50] Lamar later revealed that the track was for his major-label debut studio album and that he had plans to shoot a video for it.[51] Although the song would later be ranked No. 2 in Complex's Best 50 Songs of 2012 list, it would ultimately fail to appear on Lamar's debut.[52] In February 2012, it was announced that Fader had enlisted both Kendrick Lamar and Detroit-based rapper Danny Brown, to appear on the cover of the magazine's Spring Style issue.[53] In February, Lamar also embarked on Drake's Club Paradise Tour, opening along with fellow American rappers, ASAP Rocky and 2 Chainz.[54]

In March 2012, MTV announced that Lamar had signed a deal with Interscope Records and Aftermath Entertainment, marking the end of his career as an independent artist. Under the new deal, Lamar's projects, including his album Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, would be jointly released via Top Dawg, Aftermath, and Interscope.[55] Also in March, Lamar appeared on Last Call with Carson Daly, where he spoke on Dr. Dre and his hometown of Compton, California.[56] On April 2, 2012, Lamar premiered his commercial debut single "The Recipe", on Big Boy's Neighborhood at Power 106. The song, which serves as the first single from Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, was released for digital download the following day. The song was produced by West Coast producer Scoop DeVille and features vocals from his mentor Dr. Dre, who also mixed the record.[citation needed]

On May 14, 2012, J. Cole again spoke on his collaborative effort with Lamar. In an interview with Bootleg Kev, Cole stated: "I just started working with Kendrick the other day. We got it in, finally, again. We got maybe four or five [songs] together."[57] On May 21, Lamar made his 106 & Park debut alongside Ace Hood, joining Birdman and Mack Maine on stage to perform "B Boyz". Lamar also talked about his style and sound, Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, and his upcoming collaborative LP with J. Cole.[58] On the same date, Lamar released "War Is My Love", an original song written and recorded for the video game Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon: Future Soldier, for which he appeared in a mini promotional clip earlier that month.[59]

On July 31, 2012, Top Dawg, Aftermath, and Interscope serviced "Swimming Pools (Drank)" as the lead single from Lamar's debut album. The song's music video, directed by Jerome D, premiered on August 3, 2012, on 106 & Park. The song peaked at number 17 on the Billboard Hot 100 in its thirteenth week of gradually climbing up the chart. On August 15, 2012, singer Lady Gaga announced via Twitter that both had recorded a song titled "PartyNauseous" for his debut album.[60] However, Gaga withdrew from participation in the last moment, citing that it was due to artistic differences and had nothing to do with Lamar.[61] On August 17, 2012, Lamar released a song titled "Westside, Right on Time", featuring Southern rapper Young Jeezy.[62] The song was released as part of the "Top Dawg Entertainment Fam Appreciation Week". During 2012, Lamar also toured with the rest of Black Hippy and MMG rapper, Stalley, on BET's Music Matters Tour.[63]

Lamar's major-label debut, good kid, m.A.A.d city, was released on October 22, 2012. The album was met with critical acclaim and debuted at number two in the US, selling 242,100 copies in its first week.[64] Later that year, Fuse TV listed Lamar's single, "Backseat Freestyle" among the top 40 songs of 2012.[65] In a few months' time, the album was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). HipHopDX named Lamar "Emcee of the Year" for their 2012 Year-End honors.[66] In November, after Cole posted pictures of himself and Lamar working in the studio, the latter revealed that the two are still working on a project, but an exact release date was not given for the joint album: "We are going to drop that out the sky though. I don't want to give dates. I'm just going to let it fall" in an interview with the LA Leakers.[67]

On January 26, 2013, Lamar performed the album's first singles "Swimming Pools (Drank)" and "Poetic Justice" on NBC's sketch comedy and variety show, Saturday Night Live. In the same episode, Lamar also appeared alongside guest host Adam Levine and comedy band The Lonely Island, in an SNL Digital Short, which spawned the single "YOLO".[68][69][70] On February 22, 2013, Lamar released the video for "Poetic Justice", the Janet Jackson-sampling collaboration with Canadian rapper Drake.[71] On February 26, Lamar performed "Poetic Justice" on the Late Show with David Letterman.[72] Just nine months after its release, good kid, m.A.A.d city was certified platinum by the RIAA, Lamar's first platinum certification.[73]

In August 2013, Lamar's verse on the Big Sean track "Control", made waves across the hip-hop industry. In the verse, Lamar vows to lyrically "murder" every other up-and-coming rapper, namely J. Cole, Big K.R.I.T., Wale, Pusha T, Meek Mill, ASAP Rocky, Drake, Big Sean, Jay Electronica, Tyler, The Creator and Mac Miller. During the song, Lamar also calls himself the "King of New York", which caused controversy among several New York-based rappers.[74] Many New York rappers, including Papoose, The Mad Rapper, Mickey Factz, JR Writer, Mysonne, Joell Ortiz and more, took offense to this. Furthermore, fellow American rappers such as Meek Mill, Lupe Fiasco, Cassidy, Joe Budden, King L, Bizarre and B.o.B, among many others, released a response or diss track, within a week.[75] In the days following the track's release, Lamar's Twitter account saw a 510% increase in followers.[76]

On September 6, 2013, American recording artist and record producer Kanye West announced he would be headlining his first solo tour in five years, in support of his sixth album Yeezus (2013), with Kendrick Lamar accompanying him on tour. The Yeezus Tour began in October.[77][78] In October, it was also revealed that Lamar would be featured on Eminem's eighth studio album The Marshall Mathers LP 2.[79] On October 15, 2013, Lamar won five awards at the BET Hip Hop Awards, including Album of the Year and Lyricist of the Year (the latter of which he had also won the year before).[80] At the award show, Lamar performed "Money Trees", and was also featured in a cypher alongside his Top Dawg label-mates Jay Rock, Schoolboy Q, Isaiah Rashad, and Ab-Soul.[81][82] During an October 2013 interview with XXL, Lamar revealed that following The Yeezus Tour, he would begin to start working on his next album.[83]

In November 2013, he was named GQ's "Rapper of the Year," and was featured on the cover of the magazine's "Men of the Year" issue.[84][85][86] During the interview, he stated that he would begin recording his second major-label studio album in January 2014.[87] Following the issue's release, TDE's CEO Anthony "Top Dawg" Tiffith pulled Kendrick Lamar from performing at GQ's party that accompanies the issue, calling out writer Steve Marsh's profile, "Kendrick Lamar: Rapper of the Year," for its "racial overtones."[88][89][90][91] GQ editor-in-chief Jim Nelson responded with the following statement: "Kendrick Lamar is one of the most talented new musicians to arrive on the scene in years. That's the reason we chose to celebrate him, wrote an incredibly positive article declaring him the next King of Rap, and gave him our highest honor: putting him on the cover of our Men of the Year issue. I'm not sure how you can spin that into a bad thing, and I encourage anyone interested to read the story and see for themselves."[92][93]

Lamar received a total of seven Grammy nominations at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards (2014), including Best New Artist, Album of the Year, and Best Rap Song,[94] but did not win in any category. Many publications felt that The Recording Academy snubbed Lamar, as well as Seattle-based rapper Macklemore, who won Best Rap Album – category for which Lamar was also nominated.[95][96][97] At the ceremony, Lamar performed "M.A.A.D City" and a remix of "Radioactive" in a mash-up with American rock band Imagine Dragons at the awards ceremony.[98] The remix was again performed by Lamar and the band on February 1, 2014, during the airing of Saturday Night Live, marking Lamar's second appearance on the show.[99]

2014–2016: To Pimp a Butterfly and Untitled Unmastered

In an interview with Billboard in February 2014, Lamar stated he was planning to put out a new album the next September.[100] During the same interview, which also included Schoolboy Q, Anthony "Top Dawg" Tiffith, and Dave Free, the possibility of a debut effort from the Black Hippy collective appearing in 2014 was announced.[100] On July 31, 2014, it was announced that Lamar would premiere his short film m.A.A.d at Sundance's inaugural NEXT Fest in Los Angeles on August 9.[101] The film is inspired by good kid, m.A.A.d city, and was directed by Kahlil Joseph, who had previously worked with Lamar on the Yeezus Tour.[101] Lamar featured on the Alicia Keys song "It's On Again", which was written for the film The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (2014).[102]

On September 23, 2014, Lamar released "i" as the first single from his third album.[103] On November 15, 2014, Lamar once again appeared on Saturday Night Live as the musical guest, where he performed "i" and "Pay for It", appearing alongside Jay Rock.[104] Through his appearance, with blackout contacts and his braids partly out, Lamar paid homage to New York-based rapper Method Man, whose debut album Tical celebrated its 20th anniversary that day.[105][106] On December 17, 2014, Lamar debuted a new untitled song on one of the final episodes of The Colbert Report.[107][108] In early 2015, Lamar won Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song for his song "i" at the 57th Annual Grammy Awards.[109] On February 9, 2015, he released his third album's second single, titled "The Blacker the Berry".[110] Originally expected to be released on March 23, 2015, his new album To Pimp a Butterfly was released a week early on March 16, 2015 to rave reviews.[111] The album debuted atop the US Billboard 200 chart selling 324,000 copies in its first week,[112] and established Spotify's global first-day streaming record (9.6 million).[113] Lamar was later featured on the cover of Rolling Stone, with editor Josh Eells writing he's "arguably the most talented rapper of his generation."[11][114]

On May 17, 2015, Lamar featured on the official remix of American singer-songwriter Taylor Swift's song "Bad Blood", as well as appearing in the music video.[115] The original song is in Swift's fifth studio album 1989. The single reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and the music video won them a Grammy Award for Best Music Video and a MTV Video Music Award for Video of the Year.[116] To Pimp a Butterfly produced other three singles with accompanying music videos, "King Kunta", "Alright" and "These Walls". The music video for "Alright" received four nominations at the 2015 MTV Video Music Awards, including Video of the Year and Best Male Video.[117] The song "For Free? (Interlude)" also featured a music video,[118] as did "u" with "For Sale" as part of the short film "God Is Gangsta."[119] In October 2015, Lamar announced the Kunta's Groove Sessions Tour, which included eight shows in eight cities.[120] In early 2016, Kanye West released the track "No More Parties in L.A." on his official SoundCloud, a collaboration featuring Lamar and produced by West and Madlib.[121] Lamar also performed a new song, "Untitled 2" on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon in January.[122]

Billboard critics commented at the end of the year, "twenty years ago, a conscious rap record wouldn't have penetrated the mainstream in the way Kendrick Lamar did with To Pimp A Butterfly. His sense of timing is impeccable. In the midst of rampant cases of police brutality and racial tension across America, he spews raw, aggressive bars while possibly cutting a rug,"[123] while Pitchfork editors noted it "forced critics to think deeply about music. It's an album by the greatest rapper of his generation."[124] Producer Tony Visconti stated David Bowie's album Blackstar (2016) was influenced by Lamar's work, "we were listening to a lot of Kendrick Lamar [...] we loved the fact Kendrick was so open-minded and he didn't do a straight-up hip-hop record. He threw everything on there, and that's exactly what we wanted to do."[125] Visconti also stated this about Lamar while talking about "rule-breakers" in music.

"His album To Pimp A Butterfly broke every rule in the book and he had a number one album glued to the top of the charts. You'd think certain labels would learn form that. But they take somebody who is out there and say, 'That's what people want.' No, people want that for one week. You don't want the same song every single day of your life."[126]

Lamar won five Grammys at the 58th ceremony, including Best Rap Album for To Pimp a Butterfly.[127] Other nominations included Album of the Year and Song of the Year.[128] At the ceremony, Lamar performed a medley of "The Blacker the Berry" and "Alright".[129] It was ranked by Rolling Stone and Billboard as the best moment of the night,[130][131] with the latter writing "It was easily one of the best live TV performances in history."[129]

On March 4, 2016, Lamar released a compilation album Untitled Unmastered,[132] containing eight untitled tracks, each dated.[133] Lamar later confirmed that the tracks were unfinished demos from the recording of To Pimp a Butterfly.[134] The compilation album debuted atop the US Billboard 200.[135]

2017–present: Damn and Black Panther soundtrack; hiatus and final Top Dawg Entertainment album

On March 23, 2017, Lamar released a promotional single "The Heart Part 4".[136] A week later, Lamar released the lead single, titled "Humble", accompanied by its music video.[137] On April 7, 2017, his fourth studio album was made available for pre-order and confirmed to be released on April 14, 2017.[138][139] On April 11, Lamar announced the album title, Damn (stylized as DAMN.), as well as the track list, which confirmed guest appearances by Rihanna, Zacari, and U2.[140] The album was released on April 14, 2017 to rave reviews, with a Rolling Stone writer describing it as a combination of "the old school and the next-level."[141] It marked his third number one album on the Billboard 200 chart, and the single "Humble" became his first number one as a lead artist on the Billboard Hot 100.[142] On May 4, 2017, Damn was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[143] Lamar later released the DAMN. Collectors Edition in mid-December 2017, with the tracklist from the original album in reverse order.[144]

Along with Top Dawg Entertainment founder Anthony Tiffith, Lamar produced and curated the film soundtrack for the Marvel Studios superhero film Black Panther (2018), titled Black Panther: The Album.[145] A single from the soundtrack, "All the Stars", was released in January 2018 featuring singer SZA,[145] and it earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song.[146] Shortly thereafter, another track, titled "King's Dead", was released by Jay Rock featuring Lamar, Future and James Blake.[147] The third single, "Pray For Me", by Lamar and The Weeknd, was released in February 2018, ahead of the album's release in that month.[148][149] Black Panther: The Album was released on February 9, 2018[150] to universal acclaim.[151][152]

In January 2018, Lamar's song publishing deal with Warner/Chappell Music began to expire. Top Dawg Entertainment, which represents Lamar, is seeking $20 to $40 million for the rapper's catalogue.[153] Lamar opened the 60th Annual Grammy Awards with a medley of "XXX", "Lust", "DNA", "Humble", "King's Dead" and Rich the Kid's "New Freezer".[154] He was also nominated for seven awards, including Album of the Year and Best Rap Album for Damn, and the Record of the Year, Best Rap Performance, Best Rap Song, and Best Music Video for "Humble", and Best Rap/Sung Performance for "Loyalty" with Rihanna. Lamar ultimately won five awards at the ceremony, for Best Rap Album, Best Rap Performance, Best Rap Song, Best Music Video, and Best Rap/Sung Performance.[155] After the Black Panther soundtrack, Lamar did not release music of his own for four years.[156]

In July 2018, Lamar made his acting debut in the fifth season of the Starz drama series Power, portraying a Dominican drug addict named Laces.[157] Lamar's casting stemmed from his friendship with rapper 50 Cent, who also executive produces and stars in the series. Series creator Courtney A. Kemp said that Lamar told 50 Cent that he wanted to be on the show and 50 Cent organized the appearance.[158] Lamar wanted to portray a character that did not resemble his musical persona, and drew inspiration from various people he knew when growing up in Compton. He also compared his acting preparation to his songwriting, saying that he prefers to "always have that open space to evolve".[159] Lamar's performance was praised by critics and viewers.[160][161][162][163]

Following a four-year hiatus, Lamar teased his final album under the TDE label on his website oklama.com along with posts on his social media accounts.[164] Lamar later re-emerged with the single, "Family Ties" alongside his cousin and labelmate Baby Keem.[165]

Artistry

Influences

Kendrick Lamar has stated that Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G., Jay Z, Nas, and Eminem are his top five favorite rappers. Tupac Shakur is his biggest influence, and has influenced his music as well as his day-to-day lifestyle.[18][166][167] In a 2011 interview with Rolling Stone, Lamar mentioned Mos Def and Snoop Dogg as rappers that he listened to and took influence from during his early years.[168] He also cites now late rapper DMX as an influence: "[DMX] really [got me started] on music," explained Lamar in an interview with Philadelphia's Power 99. "That first album [It's Dark and Hell Is Hot] is classic, [so he had an influence on me]." He has also stated Eazy-E as an influence in a post by Complex saying: "I Wouldn't Be Here Today If It Wasn't for Eazy-E."[169]

In a September 2012 interview, Lamar stated rapper Eminem "influenced a lot of my style" and has since credited Eminem for his own aggression, on records such as "Backseat Freestyle".[170][171] Lamar also gave Lil Wayne's work in Hot Boys credit for influencing his style and praised his longevity.[172] He has said that he also grew up listening to Rakim, Dr. Dre, and Tha Dogg Pound.[173] In January 2013, when asked to name three rappers that have played a role in his style, Lamar said: "It's probably more of a west coast influence. A little bit of Kurupt, [Tupac], with some of the content of Ice Cube."[174] In a November 2013 interview with GQ, when asked "The Four MC's That Made Kendrick Lamar?", he answered Tupac Shakur, Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg and Mobb Deep, namely Prodigy.[175] Lamar professed to having been influenced by jazz trumpeter Miles Davis and Parliament-Funkadelic during the recording of To Pimp a Butterfly.[176]

Musical style

Lamar has been branded as the "new king of hip hop" numerous times.[177][178][179] Forbes said, on Lamar's placement as hip hop's "king", "Kendrick Lamar may or may not be the greatest rapper alive right now. He is certainly in the very short lists of artists in the conversation."[180] Lamar frequently refers to himself as the "greatest rapper alive"[181] and once called himself "The King of New York."[182]

On the topic of his music genre, Lamar has said: "You really can't categorize my music, it's human music."[183][184] Lamar's projects are usually concept albums.[185] Critics found Good Kid, M.A.A.D City heavily influenced by West Coast hip hop[186] and 90s gangsta rap.[187] His third studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly, incorporates elements of funk, jazz, soul and spoken word poetry.[188]

Called a "radio-friendly but overtly political rapper" by Pitchfork,[189] Lamar has been a branded "master of storytelling"[190] and his lyrics have been described as "katana-blade sharp" and his flow limber and dexterous.[191] Lamar's writing usually includes references to racism, black empowerment[192] and social injustice,[193] being compared to a State of Union address by The Guardian. His writing has also been called "confessional"[194] and controversial.[177] The New York Times has called Lamar's musical style anti-flamboyant, interior and complex and labelled him as a technical rapper.[195] Billboard described his lyricism as "Shakespearean".[196]

Controversies

Lyrics

Lamar's 2015 song "The Blacker the Berry" gathered controversy following the lines, "So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street, when gang-banging make me kill a nigga blacker than me? Hypocrite!" Some fans perceived the line to be Lamar judging the black community.[197] Lamar later spoke on the lyrics in a NPR interview, saying, "It's not me pointing at my community; it's me pointing at myself, I don't talk about these things if I haven't lived them, and I've hurt people in my life. It's something I still have to think about when I sleep at night."[198]

Following the release of Lamar's 2017 song "Humble", he faced backlash for the lines, "I'm so fucking sick and tired of the Photoshop / Show me something natural like afro on Richard Pryor / Show me something natural like ass with some stretch marks." He was accused of putting down sections of women who enjoy makeup in an attempt to be uplifting.[199] Female labelmate SZA later defended Lamar.[200] The model who appeared in the music video for "Humble" was also attacked on social media due to her role in the video.[201]

Feuds

In August 2013, Lamar was featured on the song "Control" by Big Sean. In his verse, Lamar called out several rappers, telling them he was going to murder his competition. The verse gathered responses and diss tracks from artists such as Joe Budden, Papoose, Meek Mill, Diddy, Lupe Fiasco, and B.o.B.[202] Rolling Stone called the single "one of the most important hip-hop songs of the last decade".[203]

Lamar has been reported to be in a feud with Drake. Complex called their relationship "complicated",[204] Genius called it a "subliminal war",[205] and GQ called it a "cold war" due to the mass popularity of both artists.[206][207] Before Lamar's "Control" verse, Lamar had been featured on Drake's "Buried Alive Interlude", Drake was featured on Lamar's single "Poetic Justice", and both were featured on A$AP Rocky's song "Fuckin' Problems".[204] Drake responded to Lamar's "Control" verse in an interview with Billboard, saying, "I know good and well that Kendrick's not murdering me, at all, in any platform."[208]

In September 2013, Drake's third album, Nothing was the Same, was released.[209] Publications such as Complex speculated that Drake had directed subliminal insults at Lamar in the song "The Language".[210] In an interview with Pitchfork a day later, Drake showed disapproval of "Control", saying he wasn't impressed with it and added, "Mind you, it'll go on– Complex and Rap Radar will give it like, verse of the millennium and all that shit or whatever." Drake later said his only competition was Kanye West, after being asked about Kendrick saying he was murdering his competition.[211] Lamar further escalated tensions in the 2013 BET Hip-Hop Awards cypher when he referred to Drake during the cypher,[212] saying, "Yeah, and nothing's been the same since they dropped 'Control' / And tucked a sensitive rapper back in his pajama clothes."[213] Stereogum noted that Lamar was referencing Drake's third studio album, Nothing was the Same, and also Drake being called overly sensitive by the media.[214]

In December 2013, Drake, whilst being interviewed by Vice, said he "stood his ground" and he has to realize "I'm being baited and I'm not gonna fall", then refusing to deny that the line on "The Language" was directed to Lamar, saying he "doesn't want to get into responses". Drake later went on to say that he acknowledged the lines in Lamar's cypher were for him and that it wasn't enough for him to prepare a response before saying they haven't seen each other since the BET cypher.[215] Several more reported subliminal lines were spoken by each rapper, four by Kendrick on the songs, "Pay for it", "King Kunta", "Darkside/Gone", and "Deep Water" and two by Drake on the songs "Used To" and "4PM In Calabasas".[204]

In June 2016, former NFL player and broadcast show host Marcellus Wiley alleged that on his ESPN show, Drake or Lamar had given an interview in which they started "talking noise" and claimed that they had problems with the other individual. The interview was eventually not aired and Wiley said it had been "destroyed".[216] Wiley said that the interview would have escalated the reported feud to become official with diss tracks being directed at the other side.[217][218] Following an almost year-long hiatus from music, Lamar released "The Heart Part 4". It was speculated that Lamar's line, "One, two, three, four, five / I am the greatest rapper alive" was a response to Drake's line, "I know I said top five, but I'm top two / And I'm not two and I got one" on the song "Gyalchester".[219][220] Kendrick proceeded to insult rappers who have ghostwriters in an interview with Rolling Stone in August 2015. It was speculated that the insult was directed towards Drake, who has seen controversy due to the use of "ghostwriters" on songs such as "RICO".[221]

Lamar has also feuded with Detroit rapper and former collaborator Big Sean. Following the release of Sean's track "Control" in August 2013 where Lamar calls Sean out and claims he's gonna "murder" him, Sean responded in praise, saying, "Alright, that's what it need to get back to, it need to get back to hip-hop, that culture."[222] In January 2015, Sean later spoke on "Control", saying that the song was "negative"[223] and a month later released the "Me, Myself, and I".[224] In October 2016, Big Sean released "No More Interviews" with shots directed at Lamar.[225]

Media

In May 2018, it was announced that Lamar was planning a departure from Spotify.[226] It came after he heard the streaming platform intended to ban now-late fellow American rapper XXXTentacion from their editorial and algorithmic playlists for his publicized acts of violence against women.[226] The removal of XXXTentacion as well as R. Kelly arrived in accordance to Spotify's new Hate Content & Hateful Conduct policy.[227] Conceived in light of the #MeToo movement, the removal policy sought to promote "openness, diversity, tolerance and respect" by removing content that promotes, advocates, or incites hatred and violence against an individual or group based on characteristics.[228][229] According to The Guardian, a representative for Kendrick Lamar personally contacted Spotify CEO Daniel Ek to air his frustrations with the policy, claiming it was censorship.[226][230] Bloomberg reported that the representative reached out to Ek and head of artist relations Troy Carter, threatening to pull his music if the company kept the policy as it stood. Anthony "Top Dawg" Tiffith, CEO of Top Dawg Entertainment, confirmed he threatened to remove music from the service in an interview with Billboard.[231][232] Kendrick had been a fan of XXXTentacion's music. He tweeted a link to his debut album 17 accompanied by praise for the controversial rapper's "raw thoughts."[233] Lamar stated, "Listen to this album if you want to feel anything."[230] In response to the criticism, Spotify reversed their policy and reinstated XXXTentacion's music back onto playlists after other artists followed suit in threatening to pull their musical works.[230]

Business ventures

In December 2014, it was announced that Lamar had started a partnership with sportswear brand Reebok.[234] In 2017, it was announced that Lamar entered a collaboration deal with Nike.[235]

On March 5, 2020, Kendrick Lamar and Dave Free announced the launching of pgLang, which is described as a multilingual, artist-friendly service company.[236][237] In a press release, Dave Free claimed that the company "is not a record label, a movie studio, or a publishing house. This is something new. In this overstimulated time, we are focused on cultivating raw expression from grassroots partnerships."[238] The announcement also featured a "visual mission statement," a four-minute short film starring Lamar, Baby Keem, Jorja Smith, and Yara Shahidi.[239]

Impact

Commenting on Lamar's discography, Esquire UK editor Olivia Ovended wrote in 2020, "even if you're not overly familiar with Lamar's back catalogue, his influence in music is everywhere, from the West Coast hip-hop now being made by Anderson .Paak. to the trap of Gucci Mane. He is—and we'll brook no argument here—the greatest rapper making music today,"[240] while The New Yorker journalist Carrie Battan considered him "California's biggest hip-hop artist since the nineteen-nineties."[241] According to American studies and media scholar William Hoynes, Lamar's progressive rap music places him in a long line of African-American artists and activists who "worked both inside and outside of the mainstream to advance a counterculture that opposes the racist stereotypes being propagated in white-owned media and culture".[242] History.com considered Lamar's Pulitzer Prize for Music award as "a sign of the American cultural elite's recognition of hip-hop as a legitimate artistic medium."[243] CNN Entertainment listed him among "the 10 artists who transformed music this decade"[244] and NME included him among "10 artists who defined the 2010s."[245] NPR writer Marcus J. Moore noticed Lamar's rap-jazz aesthetic present on his repertoire, "he's at the vanguard of this movement, proving that he too is a rule breaker, just like Miles, Herbie, Coltrane, Glasper and Hargove, who all took bold creative risks to push jazz into uncharted territory," and stated that Lamar is introducing jazz to a generation "who might only know it through their parents' old record collections."[246] Esquire US writer Matt Miller opined about the rapper's videography in 2017, crediting Lamar for "reviving" the music video as "a powerful form" of social commentary, citing as examples "Alright" and "Humble".[247]

Multiple artists have cited his work as an inspiration, including Khalid,[248] Roddy Ricch,[249] Christine and the Queens,[250] Jhené Aiko,[251] YBN Cordae,[252] Car Seat Headrest and Dua Lipa.[253] David Bowie's album Blackstar (2016) was influenced by To Pimp a Butterfly, which was noted by Rolling Stone as one of the albums that made Lamar "the decade's deepest, rangiest, most musical and consequential rapper."[254]

Achievements

Lamar has won thirteen Grammy Awards. At the 57th Grammy Awards in 2015, his single "i" earned him his first two wins: Best Rap Song and Best Rap Performance. At the 58th Grammy Awards, Lamar led the list of nominations with 11 mentions, passing Eminem and Kanye West as the rapper with the most nominations in a single night, and second overall behind Michael Jackson and Babyface, who hold the record of 12 nominations.[255][128] Lamar was the most-awarded artist at the ceremony with five.[127] good kid, m.A.A.d city, To Pimp a Butterfly and Damn have all been nominated for Album of the Year, with the latter two winning for Best Rap Album.[155] Those three albums were featured on Rolling Stone's industry-voted list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time in 2020.[256]

Lamar has received two honors in his hometown. On May 11, 2015, he received the California State Senate's Generational Icon Award from State Senator Isadore Hall III (D–Compton) who represents California's 35th district. From the senate floor, Lamar told the legislature, "Being from the City of Compton and knowing the parks that I played at and the neighborhoods, I always thought how great the opportunity would be to give back to my community off of what I do in music."[257] On February 13, 2016, Mayor of Compton, California Aja Brown presented Lamar with the key to the city, for "representing Compton's evolution, embodying the New Vision for Compton."[258]

He appeared for the first time on the Time 100 list of most influential people in 2016.[7] His debut major-label release, good kid, m.A.A.d city, was named one of "The 100 Best Debut Albums of All Time" by Rolling Stone.[259] To Pimp a Butterfly was ranked by many publications as one of the best albums of the 2010s (decade), with The Independent placing it first.[254] In 2015, Billboard included Lamar in "The 10 Greatest Rappers of All-Time."[260] Complex magazine has ranked Lamar atop "The 20 Best Rappers in Their 20s" annual lists in 2013, 2015 and 2016.[261]

DAMN. won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, making Lamar the first non-jazz or classical artist to win the award.[262] In collecting his award on May 30, 2018, new Pulitzer administrator Dana Canedy, the first woman and African American to lead the organization, told him: "Congratulations, looks like we're both making history this year."[263]

Personal life

In April 2015, Lamar became engaged to his high school girlfriend, beautician Whitney Alford.[264] He is a cousin of NBA player Nick Young[265] and rapper Baby Keem.

Lamar is a devout Christian,[266] having converted following the death of a friend.[267] He has been outspoken about his faith in his music[268] and interviews.[269] He announced to the audience during Kanye West's Yeezus Tour that he had been baptized in 2013.[269][270][271] Lamar has credited God for his fame and his "deliverance" from crime that often plagued Compton in the 1990s.[272] He also believes his career is divinely inspired and that he has a greater purpose to serve mankind, saying in an interview with Complex in 2014, "I got a greater purpose, God put something in my heart to get across and that's what I'm going to focus on, using my voice as an instrument and doing what needs to be done."[273] The introductory lines to his 2012 album Good Kid, M.A.A.D City include a form of the Sinner's Prayer.[274] His song "I" discusses his Christian faith.[275] He dressed up as Jesus for Halloween in 2014 and explained, "If I want to idolize somebody, I'm not going to do a scary monster, I'm not gonna do another artist or a human being—I'm gonna idolize the Master, who I feel is the Master, and try to walk in His light. It's hard, it's something I probably could never do, but I'm gonna try. Not just with the outfit but with everyday life. The outfit is just the imagery, but what's inside me will display longer."[276] His 2017 album Damn has a recurring theme based around religion and struggle.[277]

In the lead up to the 2012 presidential election, Lamar stated, "I don't vote. I don't do no voting, I will keep it straight up real with you. I don't believe in none of the shit that's going on in the world."[278] He went on to say that voting was useless: "When I say the president can't even control the world, then you definitely know there's something else out there pushing the buttons. They could do whatever they want to do, we['re] all puppets."[279] Several days before the 2012 presidential election, he reversed his previous claim that he was not going to vote and said that he was voting for Barack Obama because Mitt Romney did not have a "good heart".[280] Lamar later met Obama in January 2016 in promotion of Obama's My Brother's Keeper Challenge. Speaking about the meeting, Lamar said, "We tend to forget that people who've attained a certain position are human."[281] Before the meeting, Obama said in an interview that his favorite song of 2015 was Lamar's "How Much a Dollar Cost".[282]

Discography

Studio albums

- Section.80 (2011)

- Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (2012)

- To Pimp a Butterfly (2015)

- Damn (2017)

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Power[283] | Laces | Episode: "Happy Birthday" |

Concert tours

- Headlining

- Section.80 Tour (2011)[284][285]

- Good Kid, M.A.A.D City World Tour (2013)[286][287]

- Kunta Groove Sessions Tour (2015)[288]

- The Damn Tour (2017–18)[289]

- Co-headlining

- The Championship Tour (with Top Dawg Entertainment artists) (2018)[290]

- Supporting

- Kanye West – The Yeezus Tour (2013–14)[291][292]

- Drake – Club Paradise Tour (2012)[291][292]

See also

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

- List of artists who reached number one on the U.S. Rhythmic chart

- List of hip hop musicians

- List of people from California

- Music of California

References

- ^ Tylt, The. "Greatest rapper of this generation: Kendrick Lamar or J. Cole?". The Tylt. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "Is Kendrick Lamar the Greatest Rapper of Our Generation? Kehlani, LeBron James & More Weigh In". Billboard. December 22, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Braboy, Mark. "Kendrick Lamar is the artist of the decade". Insider. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "Best Albums of the Decade". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Chris (April 17, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar wins Pulitzer music prize". BBC News. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Brings Crown To Compton As 'Hottest MC in the Game". MTV. March 7, 2013. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Time 100: Kendrick Lamar". Time. April 21, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Kendrick Lamar. "Kendrick Lamar - Rapper, songwriter". Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Biography by Andy Kellman (June 17, 1987). "Kendrick Lamar | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Born and raised in Compton, Kendrick Lamar Hides a Poet's Soul Behind "Pussy & Patron" Archived January 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. LA Weekly (January 20, 2011). Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eells, Josh (June 22, 2015). "The Trials of Kendrick Lamar". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 17, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ "All You Need to Know About: Kendrick Lamar in Vancouver". Georgia Straight Vancouver's News & Entertainment Weekly. August 1, 2017. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Miranda J. "Did You Know Kendrick Lamar Was Named After One Of The Temptations? - XXL". XXL Mag. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (2011-08-31) Kendrick Lamar: Origins Of Excellence Pt. 3 Archived December 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. YouTube. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Haithcoat, Rebecca (January 20, 2011). "Born and raised in Compton, Kendrick Lamar Hides a Poet's Soul Behind "Pussy & Patron"". LA Weekly. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Talks J. Cole, XXL Freshman 2011, KiD CuDi, etc (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. December 31, 2010. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Principal of Kendrick Lamar's Compton High School Speaks on Kendrick's Influence". pigeonsandplanes.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Graham, Nadine. (January 6, 2011) Kendrick Lamar: The West Coast Got Somethin' To Say | Rappers Talk Hip Hop Beef & Old School Hip Hop Archived January 9, 2011, at the Library of Congress Web Archives. HipHop DX. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar - Track 1 (Hova Intro Freestyle)". That New Jam. March 5, 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Ozone Magazine » Issue #84 Patiently Waiting » Issue #84 – Patiently Waiting: Kendrick Lamar Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Ozonemag.com (June 23, 2010). Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ "The Black Wall Street Journal, Vol. 1 – Game > Overview". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ You Know What It Is Vol. 4: Murda Game Chronicles (track listing). Game. The Black Wall Street Records. 2007.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar (Ft. Jay Rock & Lil Wayne) – Intro (Wayne Co-Sign)". genius.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ http://hiphopdx.com, HipHopDX - (December 17, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Explains How Lil Wayne Influenced His Style". hiphopdx.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Kendrick Lamar C4 Mixtape Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine DatPiff (January 30, 2009) DatPiff. Retrieved July 8, 2011

- ^ Kendrick Lamar - Kendrick Lamar (EP) Archived March 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine [2009]. 2dopeboyz (September 14, 2010). Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Jay Rock, Kendrick Lamar, Ab-Soul and Schoolboy Q form quasi-supergroup Black Hippy Archived February 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times. (August 17, 2010). Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar – P&P 1.5 f. Ab-Soul (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Overly Dedicated (Explicit): Kendrick Lamar". Amazon.com. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar – O.D. (Mixtape)". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. September 23, 2010. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar – Chart History: R&B/Hip-Hop Albums". Billboard. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ Hanna, Mitchell. (September 27, 2010) Mixtape Release Dates: Kendrick Lamar, K-Os, Terrace Martin, Sheek Louch | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales Archived April 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. HipHop DX. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Double G News Network: GGN Ep. 2 - Special Super Hard Hitting Interview with Kendrick Lamar Archived January 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. YouTube. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ Jacobs, Allen. (December 17, 2010) Dr. Dre Says In 2011, He's Focusing On West Coast Hip Hop – Kendrick Lamar, Slim da Mobster | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales Archived April 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. HipHop DX. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Paine, Jake (December 25, 2010). "Kendrick Lamar Reacts To Dr. Dre's Cosign, Considering Aftermath". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ Kendrick Lamar Says J. Cole Collabo Mixtape is Gonna "Shock The World" Archived February 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Xxlmag.Com. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Cho, Danielle (December 2, 2010). "Indie Intro: 5 Things You Need To Know About Kendrick Lamar". Complex Music. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ The 2011 XXL Freshmen Archived November 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Xxlmag.Com. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar's 3rd Solo Album..." 2Dopeboyz. April 11, 2011. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kendrick Lamar - HiiiPoWeR (prod. by J. Cole)". 2Dopeboyz. April 13, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ Harling, Danielle (May 16, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar Hoping To Release Studio Album Next Year". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar – Ronald Reagan Era (His Evils) f. RZA". 2Dopeboyz. June 17, 2011. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "Hip Hop Album Sales: The Week Ending 7/3/2011 | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales". HipHopDX. July 6, 2011. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Gale, Alex (May 23, 2013). "20 Legendary Hip-Hop Concert Moments". Complex. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Dream Urban Presents : Kendrick Lamar Experience (Snoop Dogg Passes Torch)". YouTube. August 22, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar - A.D.H.D (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "2011 BET Awards: Cyphers (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. October 11, 2011. Archived from the original on July 8, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Kuperstein, Slava (October 4, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar "Cloud 10 [Prod. Nosaj Thing]"". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on December 7, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Kicks Off Hottest Breakthrough MCs!". MTV. December 7, 2011. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar f. Gunplay - Cartoon & Cereal | New Hip Hop Music & All The New Rap Songs 2011". HipHop DX. February 14, 2012. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ "Studio Life: Kendrick Lamar talks Club Paradise Tour & "Cartoons & Cereal"". YouTube. February 27, 2012. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Martin, Andrew (December 11, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar f/ Gunplay "Cartoon & Cereal" - The 50 Best Songs of 2012". Complex. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar & Danny Brown Cover FADER". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. February 20, 2012. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Drake 'Fought' For Intimate Campus Dates Over Stadium Tour". MTV News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Alexis, Nadeska (March 8, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar, Black Hippy Ink Deals With Interscope And Aftermath". MTV. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar on Last Call With Carson Daly (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. March 27, 2012. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "NEWS: J. COLE GIVES HIS TAKE ON WHY NAS/AZ & MF DOOM/GHOSTFACE JOINTS AREN'T DROPPIN'". SOHH.com. March 2, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar on 106 & Park (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. May 21, 2012. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar – War Is My Love". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. May 21, 2012. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar & Lady Gaga – "PARTYNAUSEOUS"". May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Explains Why Kendrick Lamar Collab Not on Album". Popdust.com. October 4, 2012. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar featuring Young Jeezy – Westside, Right on Time". Archived from the original on August 21, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Isenberg, Daniel (September 16, 2012). "Photo Recap: Kendrick Lamar, ScHoolboy Q, Ab-Soul, and Stalley Rock BET's Music Matters Tour in D.C." Complex. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Debut Sales: 242,122". Hitsdailydouble.com. October 30, 2012. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ^ "The 40 Best Songs of 2012: Fuse Staff Picks". Fuse. December 24, 2012. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ "The 2012 HipHopDX Year End Awards | Discussing Lil' Wayne, Drake & Many More Hip Hop Artists". HipHopDX. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Rebello, Ian (November 13, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole Collaboration Album Will Have No Release Date, Will "Drop Out The Sky"". The Versed. Freshcom Media LLC. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ Markman, Rob (January 22, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar To 'SNL': 'Put Me in One of Those Skits!'". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Performs on Saturday Night Live (Video)". 2DopeBoyz. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ "The Lonely Island – YOLO f. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar". 2DopeBoyz. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ Battan, Carrie (February 22, 2013). "Watch: Kendrick Lamar and Drake Star in a Story of Love and Murder in the Video for "Poetic Justice"". PitchforkMedia. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ Young, Alex (February 27, 2013). "Watch Kendrick Lamar perform 'Poetic Justice' on David Letterman". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Receives Platinum Plaque For good kid, m.A.A.d city". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. June 30, 2013. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Says He's "Trying To Murder" Drake, J. Cole, Wale on Big Sean's "Control"". Andres Tardio. August 13, 2013. Archived from the original on August 15, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "Control" responses

- Manfred, Tony (August 13, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar Verse On 'Control' Stuns Rap Game". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- "Kendrick Lamar's Verse on Big Sean's "Control" is Amazing - New Song - Fuse". Fuse.tv. August 13, 2013. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- "Joell Ortiz - Outta Control (Response to Kendrick Lamar) | New Hip Hop Music & All The New Rap Songs 2011". HipHop DX. August 13, 2013. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- "B.o.B, Fred The Godson And Los Respond To Kendrick Lamar - XXL". Xxlmag.com. August 14, 2013. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- "Cassidy "Control (Freestyle)"". Complex. August 14, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- "JR Writer - Control Yourself (Control Response) - download and stream". AudioMack. August 14, 2013. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- "Mad Rapper Kendrick Lamar "Control"". Complex. August 15, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- "Joe Budden "Control (Remix)"". Complex. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ Gruger, William (August 22, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar's 'Control' Feature Yields 510% Gain in Twitter Followers". Billboard. New York. Archived from the original on August 23, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ Battan, Carrie (September 6, 2013). "Kanye West Announces Tour With Kendrick Lamar". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Kanye West Announces Fall Arena Tour – Kendrick Lamar Opening". Glide Magazine. Glidemagazine.com. September 6, 2013. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "MMLP2 Tracklisting | NOV.5.2013". EMINEM. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ "2013 BET Hip Hop Awards: The Complete Winners List". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ "2013 BET Hip Hop Awards: Performances". 2dopeboyz.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "2013 BET Cypher: TDE w/ Kendrick Lamar, ScHoolboy Q, Ab-Soul, Jay Rock & Isaiah Rashad (Video)". 2dopeboyz.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar on TDE, His "Control" Verse And Fame From XXL's Oct/Nov Cover Story - XXL". Xxlmag.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar on Drake: "[We're] Pretty Cool, and I Would Be Okay If We Weren't"". MissInfo.tv. November 11, 2013. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Golden, Zara (November 11, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar Talks Drake in GQ's Men of the Year Issue". The Fader. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Named GQ's Rapper of the Year, Talks About Drake: "[We're] Pretty Cool, and I Would Be Okay if We Weren't"". Complex. November 11, 2013. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "5 Things XXL Learned From Kendrick Lamar's GQ Story - XXL". Xxlmag.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Ortiz, Edwin (November 15, 2013). "TDE CEO Attacks GQ Story on Kendrick Lamar as Having 'Racial Overtones,' Pulls Lamar From GQ Party". Complex. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar's Camp Takes Aim at GQ's 'Racial' Man of the Year Cover Story". MTV. November 15, 2013. Archived from the original on February 6, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "TDE Slams GQ Over Kendrick Lamar Story | Music Matters | News". BET. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Pulled From GQ Party in Response to Mag Profile". Gawker.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "GQ Responds To Kendrick Lamar Controversy". Stereogum. November 19, 2013. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "GQ 'Mystified' At Kendrick Lamar Cover Controversy". MTV. November 18, 2013. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Grammy Awards 2014: Full Nominations List". Billboard. December 6, 2013. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Responds to Macklemore Grammys Snub: Everything Happens for a Reason | E! Online UK". E!. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Emmanuel C.M. (January 29, 2014). "Exclusive: Kendrick Lamar Says "Everything Happens For A Reason" After Grammy Snub - XXL". Xxlmag.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Sperry, April (January 26, 2014). "Here Are The Biggest Snubs of the 2014 Grammys". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Llacoma, Janice (January 26, 2014). "Kendrick Lamar & Imagine Dragons "m.A.A.d city" & "Radioactive" (2014 GRAMMY Performance)". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (February 2, 2014). "Watch: Kendrick Lamar Joins Imagine Dragons on "Saturday Night Live"". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 7, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Top Dawg's Kendrick Lamar & ScHoolboy Q Cover Story: Enter the House of Pain". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kendrick Lamar To Debut". HotNewHipHop. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Lee, Ashley (March 31, 2014). "Alicia Keys, Kendrick Lamar Release 'Amazing Spider-Man 2' Song (Audio)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Frydenlund, Zach (September 23, 2014). "Listen to Kendrick Lamar's "I"". Complex. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Makes a Triumphant Return to 'SNL'". Rolling Stone. November 16, 2014. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Performs "i", "Pay for It" With Jay Rock on "Saturday Night Live"". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "AllHipHop " Kendrick Lamar Pays Homage To Method Man During SNL Performance (VIDEO)". AllHipHop. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Debuts New Song on 'The Colbert Report'". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Watch Kendrick Lamar Debut A New Song on Colbert". Stereogum. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Cries Tears of Joy Over Kendrick Lamar's Grammy Wins". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 13, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar premieres 'The Blacker The Berry', his intense, racially-charged new single – listen". Consequence of Sound. February 9, 2015. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Ryan, Patrick (March 16, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar's new album arrives early". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (March 25, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar Earns His First#1 Album on Billboard 200 Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "Yasiin Bey (Mos Def) Joined Kendrick Lamar for 'Alright' Performance at Osheaga". Billboard. August 3, 2015. Archived from the original on August 6, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "5 Influential Rappers That Broke The Mental Health Stigma". The Huffington Post. July 27, 2016. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Strecker, Erin (May 17, 2015). "Taylor Swift's 'Bad Blood' Video Premieres". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ Trust, Gary (May 27, 2015). "Taylor Swift's 'Bad Blood' Blasts to#1 on Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "2015 MTV Video Music Awards Nominees Revealed: Taylor Swift, Kendrick Lamar, Ed Sheeran & More". Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Stutz, Colin (July 31, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar Goes 'Looney' Living the American Dream in 'For Free?' Video: Watch". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 5, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (December 31, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar Confronts Demons, Temptation in 'God Is Gangsta' Short". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar announces the Kunta's Groove Sessions Tour". rap-up. October 5, 2015. Archived from the original on November 8, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ "Kanye West Drops 'No More Parties in L.A.' With Kendrick Lamar". Rolling Stone. January 18, 2016. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Unveils Powerful New Song 'Untitled 2' on 'Fallon'". Rolling Stone. January 8, 2016. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ "Billboard.com's 25 Best Albums of 2015: Critics' Picks". Billboard. December 15, 2015. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ "Staff Lists: The 50 Best Albums of 2015". Pitchfork Media. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Greene, Andy (November 23, 2015). "The Inside Story of David Bowie's Stunning New Album, 'Blackstar'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ "Bowie producer says music needs more 'rule-breakers' like Frank Ocean and Kendrick Lamar - NME". NME. March 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Grammys 2016: The Complete Winners List". Rolling Stone. February 16, 2016. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Grammy Nominations 2016: See the Full List of Nominees". Billboard. December 7, 2015. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lynch, Joe (February 16, 2016). "2016 Grammys Performances Ranked From Worst to Best". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Rolling Stone staff (February 16, 2016). "Grammys 2016: 20 Best and Worst Moments". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 17, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ Payne, Chris (February 16, 2016). "The Best & Worst Moments of the 2016 Grammys". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ "untitled unmastered". iTunes Store (US). Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "New Kendrick Lamar Project untitled unmastered. Surfaces Online". Pitchfork. March 3, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Gordon, Jeremy (March 4, 2016). "Kendrick Lamar Releases New Album untitled unmastered". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (March 13, 2016). "Kendrick Lamar's Surprise 'Untitled' Album Debuts at#1 on Billboard 200 Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Drops New Single 'The Heart Part 4' - XXL". XXL Mag. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Shares Video for New Song "HUMBLE.": Watch". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar to Release New Album on April 14th". Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Kennedy, Gerrick D. (April 7, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar's new album arrives April 14". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Enlists Rihanna and U2 for New Album DAMN". Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R. (April 18, 2017). "Review: Kendrick Lamar Moves From Uplift to Beast Mode on Dazzling 'Damn.'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Trust, Gary (April 24, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar's 'Humble.' Hits#1 on Billboard Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Tom, Lauren. "Kendrick Lamar Goes Platinum With 'DAMN.'". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ "Collector's Edition of Kendrick Lamar's 'Damn' With Tracks in Reverse Order Might Be on the Way". Complex. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tiffany, Kaitlyn (January 4, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar produced the soundtrack for Black Panther". The Verge. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Awards for Kendrick Lamar at IMDb

- ^ Grey, Julia (January 11, 2018). "Jay Rock Drops 'Black Panther' Soundtrack Cut 'King's Dead,' Feat. Kendrick Lamar, Future & James Blake". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Pray For Me: Kendrick Lamar and The Weeknd release 'Black Panther' collaboration". NME. February 2, 2018. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "Everything we know about the Marvel superhero film 'Black Panther'". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar releases The Black Panther soundtrack: Stream". Consequence of Sound. February 9, 2018. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (February 9, 2018). "Black Panther soundtrack review - Kendrick Lamar's Superfly moment". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ Jenkins, Craig. "Kendrick Lamar's Black Panther: The Album Is More Than Just a Tasteful Tie-in". Vulture. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Eyeing New Publishing Deal: Sources". Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ Hooton, Christopher (January 29, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar gave the Grammys the performance it doesn't deserve: Watch". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chow, Andrew R. (January 28, 2018). "Grammy 2018 Winners: Full List". Variety. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Coleman II, C. Vernon (November 14, 2020). "Kendrick Lamar Has Six Albums of Unreleased Music, Says Engineer". XXL Magazine. Townsquare Media, Inc.

- ^ France, Lisa Respers (July 30, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar wins raves for his 'Power' appearance". CNN. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Elber, Lynn (July 29, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar is 'fearless' in tackling Power guest role". Associated Press. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Burks, Tosten (August 1, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar Wants to be Out of the Ordinary with His Acting Career". XXL. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (July 29, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar Turns It Up In 'Power' With Dramatic Debut – Review". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Roots, Kimberly (July 29, 2018). "Power Recap: Crappy Birthday". TVLine. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Montgomery, Sarah Jasmine (July 29, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar's Been Getting Props for His Acting Debut on 'Power'". Complex. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Moss, Kyle (July 30, 2018). "Fans Go Nuts On Twitter Over Kendrick Lamar's Acting Debut On 'Power'". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Yoo, Noah (August 20, 2021). "Kendrick Lamar Says He's Producing His "Final TDE Album"". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar returns on collaboration with Baby Keem, 'Family Ties'". NME. August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar defines HiiiPower & having a vision of 2pac". YouTube. July 13, 2011. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar 'HiiiPOWER' OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO". YouTube. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Barshad, Amos (October 23, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar Makes New Friends". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ Kuperstein, Slava (September 23, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Cites DMX As An Influence & Discusses Learning From Dr. Dre's Mistakes". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Says Eminem "Definitely" Influenced His Style, Calls Him A "Genius"". YouTube. September 28, 2012. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Says 'Backseat Freestyle' Was Influenced By Eminem". Vibe. October 14, 2013. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Explains How Lil Wayne Influenced His Style | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales". HipHopDX. December 17, 2012. Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Wants To Rap With Jay-Z & Nas, Says He's "On Their Toes" | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales". HipHopDX. December 21, 2012. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Ryon, Sean (January 28, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar Says He's A Mixture of Kurupt, Tupac & Ice Cube | Get The Latest Hip Hop News, Rap News & Hip Hop Album Sales". HipHop DX. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Marsh, Steve (November 13, 2013). "The Four MC's That Made Kendrick Lamar: The Q". GQ. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.