Kings of Persis

Kings of Persis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| after 132 BCE–224 CE | |||||||||

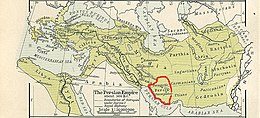

Approximate extent of the kingdom | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Parthian Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Istakhr | ||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Persian | ||||||||

| Religion | Zoroastrianism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• after 132 BCE – ? | Darayan I (first) | ||||||||

• 211/2–224 | Ardakhshir V (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late antiquity | ||||||||

• Established | after 132 BCE | ||||||||

• Incorporated into the Sasanian Empire | 224 CE | ||||||||

| Currency | Drachm | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Iran | ||||||||

| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

The Kings of Persis, also known as the Darayanids, were a series of Persian kings, who ruled the region of Persis in southwestern Iran, from the 2nd century BCE to 224 CE. They ruled as sub-kings of the Parthian Empire, until they toppled them and established the Sasanian Empire.[1] They effectively formed some Persian dynastic continuity between the Achaemenid Empire (6th century BCE – 4th century BCE) and the Sasanian Empire (3rd century CE – 7th century CE).[1]

History[]

Persis (also known as Pars), a region in the southwestern Iranian plateau, was the homeland of a southwestern branch of the Iranian peoples, the Persians.[2] It also was also the birthplace of the first Iranian Empire, the Achaemenids.[2] The region served as the center of the empire until its conquest by the Macedonian king Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC).[2] Since the end of the 3rd or the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, Persis was ruled by local dynasts subject to the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire.[1] These dynasts held the ancient Persian title of frataraka ("leader, governor, forerunner"), which is also attested in the Achaemenid-era.[3] Later under the frataraka Wadfradad II (fl. 138 BCE) was made a vassal of the Iranian Parthian (Arsacid) Empire.[1] The frataraka were shortly afterwards replaced by the Kings of Persis, most likely at the accession of the Arsacid monarch Phraates II (r. 132–127 BC).[4] Unlike the fratarakas, the Kings of Persis used the title of shah ("king"), and laid foundations to a new dynasty, which may be labelled the Darayanids.[4]

Sub-kings of the Parthian Empire[]

According to Strabo, the early kings of Persis were tributaries to the Seleucid rulers, until c.140 BC, when the Parthians conquered the region:[5]

The Persians have kings who are subject to other kings, formerly of the kings of Macedonia, but now to the kings of the Parthians.

The Parthian Empire then took control of Persis under Arsacid king Mithridates I (ca. 171–138 BC), but visibly allowed local rulers to remain, and permitted the emission of coinage bearing the title of Mlk ("King").[1] From then on, the coinage of the Kings of Persis would become quite Parthian in character and style.[1]

Under the Parthians, these dynasts were called kings and their title appeared on their coins: for example "dʾryw MLKʾ BRH wtprdt MLKʾ" (Dārāyān the King, son of Wādfradād the King).[1] The Arsacid influence is very clear in the coinage, and Strabo also reports (15. 3.3) that during the time of Augustus (27 BCE–14 CE), the kings of the Persians were as subservient to the Parthians as they had been earlier to the Macedonians:[1]

But afterwards different princes occupied different palaces; some, as was natural, less sumptuous, after the power of Persis had been reduced first by the Macedonians, and secondly still more by the Parthians. For although the Persians have still a kingly government, and a king of their own, yet their power is very much diminished, and they are subject to the king of Parthia.

Establishment of the Sasanian Empire[]

Under Vologases V (r. 191–208), the Parthian Empire was in decline, due to wars with the Romans, civil wars and regional revolts.[8] The Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) had invaded the Parthian domains in 196, and two years later did the same, this time sacking the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon.[8] At the same time, revolts occurred in Media and Persis.[8]

The Iranologist Touraj Daryaee argues that the reign of Vologases V was "the turning point in Parthian history, in that the dynasty lost much of its prestige."[8] The kings of Persis were now unable to depend on their weakened Parthian overlords.[8] Indeed, in 205/6, a local Persian ruler named Pabag rebelled and overthrew the Bazrangid ruler of Persis, Gochihr, taking Istakhr for himself.[9][8] According to the medieval Iranian historian al-Tabari (d. 923), it was at the urging of his son Ardashir that Pabag rebelled. However, Daryaee considers this statement unlikely, and states that it was in reality Shapur that helped Pabag to capture Istakhr, as demonstrated by the latter's coinage which has portraits of both them.[10]

There he appointed his eldest son Shapur as his heir.[8] This was much to the dislike of Ardashir, who had become the commander of Darabgerd after the death of Tiri.[8][11] Ardashir in an act of defiance, left for Ardashir-Khwarrah, where he fortified himself, preparing to attack his brother Shapur after Pabag's death.[8][a] Pabag died a natural death sometime between 207 and 210 and was succeeded by Shapur, who became king of Persis.[13] After his death, both Ardashir and Shapur started minted coins with the title of "king" and the portrait of Pabag.[14] The observe of Shapur's coins had the inscription "(His) Majesty, king Shapur" and the reverse had "son of (His) Majesty, king Pabag".[15] Shapur's reign, however, proved short; he died under obscure conditions in 211/2.[15][8] Ardashir thus succeeded Shapur as Ardashir V, and went on to conquer the rest of Iran, establishing the Sasanian Empire in 224 as Ardashir I.[16]

Coinage[]

The coinage of the Kings of Persis consists in individualized portraits of the rulers on the obverse, and often the rulers shown in a devotional role on the reverse.[17] The style of the coins is often influenced by Parthian coinage, particularly in respect to the dress and the headgear of the rulers.[1] A reverse legend in Aramaic, using the Aramaic script, gives the name of the ruler and his title (