Kraken

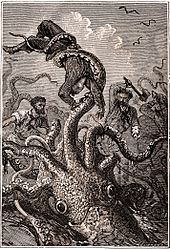

The kraken (/ˈkrɑːkən/)[1] is a legendary sea monster of gigantic size and cephalopod-like appearance in Scandinavian folklore. According to the Norse sagas, the kraken dwells off the coasts of Norway and Greenland and terrorizes nearby sailors. Authors over the years have postulated that the legend may have originated from sightings of giant squids that may grow to 13–15 meters (40–50 feet) in length. The sheer size and fearsome appearance attributed to the kraken have made it a common ocean-dwelling monster in various fictional works. The kraken has been the focus of many sailors passing the North Atlantic and especially sailors from the Nordic countries. Throughout the centuries, the kraken has been a staple of sailors' superstitions and mythos.

Etymology[]

The English word kraken is taken from the modern Scandinavian languages,[2][3] originating from the Old Norse word kraki.[4] In both Norwegian and Swedish, Kraken is the definite form of krake, a word designating an unhealthy animal or something twisted (cognate with the English crook and crank).[5] In modern German, Krake (plural and oblique cases of the singular: Kraken) means octopus, but can also refer to the legendary kraken. Kraken is also an old Norwegian word for octopus[4] and an old euphemism in Swedish for whales, used when the original word became taboo as it was believed it could summon the creatures.[3][6]

History[]

After returning from Greenland, the anonymous author of the Old Norwegian natural history work Konungs skuggsjá (c. 1250) described in detail the physical characteristics and feeding behavior of these beasts. The narrator proposed there must be only two in existence, stemming from the observation that the beasts have always been sighted in the same parts of the Greenland Sea, and that each seemed incapable of reproduction, as there was no increase in their numbers. The Kraken’s history is formed from Scandinavian Folklore.

There is a fish that is still unmentioned, which it is scarcely advisable to speak about on account of its size, because it will seem to most people incredible. There are only a very few who can speak upon it clearly, because it is seldom near land nor appears where it may be seen by fishermen, and I suppose there are not many of this sort of fish in the sea. Most often in our tongue we call it hafgufa ("kraken" in e.g. Laurence M. Larson's translation[7]). Nor can I conclusively speak about its length in ells, because the times he has shown before men, he has appeared more like land than like a fish. Neither have I heard that one had been caught or found dead; and it seems to me as though there must be no more than two in the oceans, and I deem that each is unable to reproduce itself, for I believe that they are always the same ones. Then too, neither would it do for other fish if the hafgufa were of such a number as other whales, on account of their vastness, and how much subsistence that they need. It is said to be the nature of these fish that when one shall desire to eat, then it stretches up its neck with a great belching, and following this belching comes forth much food, so that all kinds of fish that are near to hand will come to present location, then will gather together, both small and large, believing they shall obtain their food and good eating; but this great fish lets its mouth stand open the while, and the gap is no less wide than that of a great sound or bight. And nor the fish avoid running together there in their great numbers. But as soon as its stomach and mouth is full, then it locks together its jaws and has the fish all caught and enclosed, that before greedily came there looking for food.[8]

In the late-13th-century version of the Old Icelandic saga Örvar-Oddr is an inserted episode of a journey bound for Helluland (Baffin Island) which takes the protagonists through the Greenland Sea, and here they spot two massive sea-monsters called Hafgufa ("sea mist") and Lyngbakr ("heather-back").[a][b] The hafgufa is believed to be a reference to the kraken:

[N]ú mun ek segja þér, at þetta eru sjáskrímsl tvau, heitir annat hafgufa, en annat lyngbakr; er hann mestr allra hvala í heiminum, en hafgufa er mest skrímsl skapat í sjánum; er þat hennar náttúra, at hon gleypir bæði menn ok skip ok hvali ok allt þat hon náir; hon er í kafi, svá at dægrum skiptir, ok þá hon skýtr upp hǫfði sínu ok nǫsum, þá er þat aldri skemmr en sjávarfall, at hon er uppi. Nú var þat leiðarsundit, er vér fórum á millum kjapta hennar, en nasir hennar ok inn neðri kjaptrinn váru klettar þeir, er yðr sýndiz í hafinu, en lyngbakr var ey sjá, er niðr sǫkk. En Ǫgmundr flóki hefir sent þessi kvikvendi í móti þér með fjǫlkynngi sinni til þess at bana þér ok ǫllum mǫnnum þínum; hugði hann, at svá skyldi hafa farit fleiri sem þeir, at nú druknuðu, en hann ætlaði, at hafgufan skyldi hafa gleypt oss alla. Nú siglda ek því í gin hennar, at ek vissa, at hún var nýkomin upp.[9]

Now I will tell you that there are two sea-monsters. One is called the hafgufa [sea-mist[a]], another lyngbakr [heather-back[a]]. It [the lyngbakr] is the largest whale in the world, but the hafgufa is the largest monster in the sea. It is the nature of this creature to swallow men and ships, and even whales and everything else within reach. It stays submerged for days, then rears its head and nostrils above surface and stays that way at least until the change of tide. Now, that sound we just sailed through was the space between its jaws, and its nostrils and lower jaw were those rocks that appeared in the sea, while the lyngbakr was the island we saw sinking down. However, Ogmund Tussock has sent these creatures to you by means of his magic to cause the death of you [Odd] and all your men. He thought more men would have gone the same way as those that had already drowned [i.e., to the lyngbakr which wasn't an island, and sank], and he expected that the hafgufa would have swallowed us all. Today I sailed through its mouth because I knew that it had recently surfaced.

The famous Swedish 18th century naturalist Carl Linnaeus included the kraken in the first edition of its systematic natural catalog Systema Naturae from 1735. There he gave the animal the scientific name Microcosmus, but omitted it in later editions.

Kraken were extensively described by Erik Pontoppidan, bishop of Bergen, in his Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie "The First Attempt at [a] Natural History of Norway" (Copenhagen, 1752).[10][11] Pontoppidan made several claims regarding kraken, including the notion that the creature was sometimes mistaken for an island[12] and that the real danger to sailors was not the creature itself but rather the whirlpool left in its wake.[13] However, Pontoppidan also described the destructive potential of the giant beast: "it is said that if [the creature's arms] were to lay hold of the largest man-of-war, they would pull it down to the bottom".[12][13][14] According to Pontoppidan, Norwegian fishermen often took the risk of trying to fish over kraken, since the catch was so plentiful[15] (hence the saying "You must have fished on Kraken"[16]). Pontoppidan also proposed that a specimen of the monster, "perhaps a young and careless one", was washed ashore and died at Alstahaug in 1680.[14][17] By 1755, Pontoppidan's description of the kraken had been translated into English.[18]

Swedish author Jacob Wallenberg described the kraken in the 1781 work Min son på galejan ("My son on the galley"):

Kraken, also called the Crab-fish, which is not that huge, for heads and tails counted, he is no larger than our Öland is wide [i.e., less than 16 km or 10 miles] ... He stays at the sea floor, constantly surrounded by innumerable small fishes, who serve as his food and are fed by him in return: for his meal, (if I remember correctly what E. Pontoppidan writes,) lasts no longer than three months, and another three are then needed to digest it. His excrements nurture in the following an army of lesser fish, and for this reason, fishermen plumb after his resting place ... Gradually, Kraken ascends to the surface, and when he is at ten to twelve fathoms [18 to 22 m; 60 to 72 ft], the boats had better move out of his vicinity, as he will shortly thereafter burst up, like a floating island, spurting water from his dreadful nostrils and making ring waves around him, which can reach many miles. Could one doubt that this is the Leviathan of Job?[19]

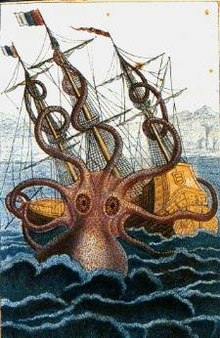

In 1802, the French malacologist Pierre Dénys de Montfort recognized the existence of two kinds of giant octopus in Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques, an encyclopedic description of mollusks.[20] Montfort claimed that the first type, the kraken octopus, had been described by Norwegian sailors and American whalers, as well as ancient writers such as Pliny the Elder. The much larger second type, the colossal octopus, was reported to have attacked a sailing vessel from Saint-Malo, off the coast of Angola.[12]

Montfort later dared more sensational claims. He proposed that ten British warships, including the captured French ship of the line Ville de Paris, which had mysteriously disappeared one night in 1782, must have been attacked and sunk by giant octopuses. The British, however, knew—courtesy of a survivor from Ville de Paris—that the ships had been lost in a hurricane off the coast of Newfoundland in September 1782, resulting in a disgraceful revelation for Montfort.[15]

Appearance and origins[]

Since the late 18th century, the kraken has been depicted in a number of ways, primarily as a large octopus-like creature, and it has often been alleged that Pontoppidan's kraken might have been based on sailors' observations of the giant squid. The kraken is also depicted to have spikes on its suckers. In the earliest descriptions, however, the creatures were more crab-like[17] than octopus-like, and generally possessed traits that are associated with large whales rather than with giant squid. An ancient, giant cephalopod resembling the legendary kraken has been proposed as responsible for the deaths of ichthyosaurs during the Triassic Period.[21]

In popular culture[]

Although fictional and the subject of myth, the legend of the Kraken continues to the present day, with numerous references in film, literature, television, and other popular culture topics.[22] Examples are Alfred Tennyson's 1830 irregular sonnet The Kraken,[23] references in Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick (Chapter 59 "Squid"),[24] the novel The Kraken Wakes, the Kraken of Marvel Comics, the 1981 film Clash of the Titans and its 2010 remake of the same name, and the Seattle Kraken professional ice hockey team. Krakens also appear in video games such as Sea of Thieves, God of War II and Return of the Obra Dinn. The kraken was also featured in two of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, primarily in the 2006 film, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, as the pet of the fearsome Davy Jones, the main antagonist of the film. The kraken also makes an appearance in the film's sequel, At World's End.

See also[]

Notes[]

Explanatory notes[]

- ^ a b c "sea-reek" and "heather-back" (Edwards & Pálsson 1970, Ch. 21, p. 69).

- ^ The episode occurs in the late fourteenth century text (Edwards & Pálsson 1970, p. xxi), and in codices ABE from 15th century, and ca. 1700 (Boer 1888, p. 132).

Citations[]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ^ "kraken". The Free Online Dictionary.

- ^ a b "krake". Svenska Akademiens ordbok (in Swedish).

- ^ a b "kraken". Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka.

- ^ "krake". Bokmålsordboka (in Norwegian).

- ^ Terrell, Peter; et al. (Eds.) (1999). German Unabridged Dictionary (4th ed.). Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-270235-1

- ^ Larson 1917, p. 125

- ^ Keyser, Munch & Unger 1848, Chapter 12, p. 32

- ^ Boer 1888, p. 132

- ^ Pontoppidan, Erich: Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie, Copenhagen: Berlingske Arvingers Bogtrykkerie, 1752.

- ^ Pontoppidan, Erich: Versuch einer natürlichen Geschichte Norwegens (Copenhagen, 1753–54).

- ^ a b c Hamilton, R. (1839). The Kraken. In: The Natural History of the Amphibious Carnivora, including the Walrus and Seals, also of the Herbivorous Cetacea, &c. W. H. Lizars, Edinburgh. pp. 327–336.

- ^ a b [Anonymous] (1849). New Books: An Essay on the credibility of the Kraken. The Nautical Magazine 18(5): 272–276.

- ^ a b Sjögren, Bengt (1980). Berömda vidunder. Settern. ISBN 91-7586-023-6 (in Swedish)

- ^ a b "Kraken". Encyclopædia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge . 21. B. Fellowes, London. 1845. pp. 255–258.

- ^ Bringsværd, T.A. (1970). The Kraken: A slimy giant at the bottom of the sea. In: Phantoms and Fairies: From Norwegian Folklore. Johan Grundt Tanum Forlag, Oslo. pp. 67–71.

- ^ a b "Kraken". Encyclopædia Perthensis; or Universal Dictionary of the Arts, Sciences, Literature, &c.. 12 (2nd ed.). John Brown, Edinburgh. 1816. pp. 541–542.

- ^ The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer Vol. 24 (Appendix, 1755). pp. 622–624.

- ^ Wallenberg, J. (1835). Min son på galejan, eller en ostindisk resa innehållande allehanda bläckhornskram, samlade på skeppet Finland, som afseglade ifrån Götheborg i Dec. 1769, och återkom dersammastädes i Junii 1771. (5th ed.). Elméns och Granbergs Tryckeri, Stockholm. (in Swedish)

- ^ Denys de Montfort, Pierre (1801–1805). Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière des mollusques. 102. Paris: L'Imprimerie de F. Dufart. pp. 256–412 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (2011). "Kraken versus ichthyosaur: let battle commence". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.586. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Stowell, Barbara A. (2009). "Under the Sea: The Kraken in Culture". cgdclass.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "The Kraken (1830)". Victorianweb.org. 11 January 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Melville, Herman (2001) [1851]. Moby Dick; Or, The Whale. Project Gutenberg.

Bibliography[]

Texts[]

- Boer, Richard Constant, ed. (1888). Ǫrvar-Odds saga. E. J. Brill. p. 132.

- Keyser, Rudolph; Munch, Peter Andreas; Unger, Carl Rikard, eds. (1848). "Chapter 12". Speculum regale. Konungs-skuggsjá. Christiana: Carl C. Werner. p. 32.

- McMenamin, M.A.S. (2016). Deep Bones. In: M.A.S. McMenamin Dynamic Paleontology: Using Quantification and Other Tools to Decipher the History of Life. Springer, Cham. pp. 131–158. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22777-1_9 ISBN 978-3-319-22776-4.

- Rafn, Carl Christian, ed. (1829). Örvar-Odds saga. Fornaldarsögur Norðurlanda. 2. Copenhagen: Enni Poppsku. pp. 248–249.

Translations[]

- Edwards, Paul; Pálsson, Hermann (translators) (1970). Arrow-Odd: a medieval novel. New York University Press.

- Larson, Laurence Marcellus, ed. (1917). The King's Mirror: (Speculum Regalae – Konungs Skuggsjá). New York: Twaine Publishers / American-Scandinavian Foundation. pp. 119–. ISBN 9780805733280.

External links[]

| Look up Kraken in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Mythological aquatic creatures

- Mythological cephalopods

- Scandinavian legendary creatures

- Sea monsters