Leviathan

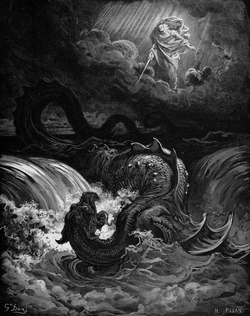

Leviathan (/lɪˈvaɪ.əθən/; לִוְיָתָן, Līvəyāṯān) is a creature with the form of a sea serpent in Judaism. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, and the Book of Amos; it is also mentioned in the Book of Enoch.

In Christianity and Gnosticism, the Leviathan is a demonic dragon, often threatening to eat the damned after life and an embodiment of chaos. In the end, they are annihilated. Christian theologians identified Leviathan with the demon of the deadly sin envy. According to the Ophite diagram, the Leviathan encapsulates the space of the material world.

The Leviathan of the Book of Job is a reflection of the older Canaanite Lotan, a primeval monster defeated by the god Baal Hadad. Parallels to the role of Mesopotamian Tiamat defeated by Marduk have long been drawn in comparative mythology, as have been wider comparisons to dragon and world serpent narratives such as Indra slaying Vrtra or Thor slaying Jörmungandr.[1] Leviathan also figures in the Hebrew Bible as a metaphor for a powerful enemy, notably Babylon (Isaiah 27:1). Some 19th century scholars pragmatically interpreted it as referring to large aquatic creatures, such as the crocodile.[2] The word later came to be used as a term for great whale, and for sea monsters in general.

Etymology and origins[]

Gesenius (among others) argued the name לִוְיָתָן was derived from the root לוה lvh "to twine; to join", with an adjectival suffix ן- ָ, for a literal meaning of "wreathed, twisted in folds".[2] If it exists, the adjectival suffix ן- ָ (as opposed to -ון) is otherwise unattested except perhaps in Nehushtan, whose etymology is unknown; the ת would also require explanation, as Nechushtan is formed from nechoshet and Leviathan from liveyah; the normal-pattern f.s. adjective would be לויון, liveyon. Other philologists, including Leskien, thought it a foreign loanword.[3] A third school considers it a proper noun.[4] Bauer proposed לוית+תן, for "wreath of serpent."[5]

Both the name and the mythological figure are a direct continuation of the Ugaritic sea monster Lôtān, one of the servants of the sea god Yammu defeated by Hadad in the Baal Cycle.[6][7] The Ugaritic account has gaps, making it unclear whether some phrases describe him or other monsters at Yammu's disposal such as Tunannu (the biblical Tannin).[8] Most scholars agree on describing Lôtān as "the fugitive serpent" (bṯn brḥ)[7] but he may or may not be "the wriggling serpent" (bṯn ʿqltn) or "the mighty one with seven heads" (šlyṭ d.šbʿt rašm).[9] His role seems to have been prefigured by the earlier serpent Têmtum whose death at the hands of Hadad is depicted in Syrian seals of the 18th–16th century BC.[9]

Sea serpents feature prominently in the mythology of the ancient Near East.[10] They are attested by the 3rd millennium BC in Sumerian iconography depicting the god Ninurta overcoming a seven-headed serpent. It was common for Near Eastern religions to include a Chaoskampf: a cosmic battle between a sea monster representing the forces of chaos and a creator god or culture hero who imposes order by force.[11] The Babylonian creation myth describes Marduk's defeat of the serpent goddess Tiamat, whose body was used to create the heavens and the earth.[12]

Tanakh[]

The Leviathan specifically is mentioned six times in the Tanakh, in Job 3:8, Job 40:15–41:26, Psalm 74:14, Psalm 104:26 and twice in Isaiah 27:1.

Job 41:1–34 is dedicated to describing him in detail: "Behold, the hope of him is in vain; shall not one be cast down even at the sight of him?"[13] Included in God's lengthy description of his indomitable creation is Leviathan's fire-breathing ability, his impenetrable scales, and his overall indomitability in Job 41.In Psalm 104, God is praised for having made all things, including Leviathan, and in Isaiah 27:1, he is called the "tortuous serpent" who will be killed at the end of time.[10]

The mention of the Tannins in the Genesis creation narrative[14] (translated as "great whales" in the King James Version),[15] in Job, and in the Psalm[16] do not describe them as harmful but as ocean creatures who are part of God's creation. The element of competition between God and the sea monster and the use of Leviathan to describe the powerful enemies of Israel[17] may reflect the influence of the Mesopotamian and Canaanite legends or the contest in Egyptian mythology between the Apep snake and the sun god Ra. Alternatively, the removal of such competition may have reflected an attempt to naturalize Leviathan in a process that demoted it from deity to demon to monster.[18][19][page needed]

Judaism[]

Later Jewish sources describe Leviathan as a dragon who lives over the sources of the Deep and who, along with the male land-monster Behemoth, will be served up to the righteous at the end of time. The Book of Enoch (60:7–9) describes Leviathan as a female monster dwelling in the watery abyss (as Tiamat), while Behemoth is a male monster living in the desert of Dunaydin ("east of Eden").[10]

When the Jewish midrash (explanations of the Tanakh) were being composed, it was held that God originally produced a male and a female leviathan, but lest in multiplying the species should destroy the world, he slew the female, reserving her flesh for the banquet that will be given to the righteous on the advent of the Messiah.[20][21] A similar description appears in Book of Enoch (60:24), which describes how the Behemoth and Leviathan will be prepared as part of an eschatological meal.

Rashi's commentary on Genesis 1:21 repeats the tradition:

the...sea monsters: The great fish in the sea, and in the words of the Aggadah (B.B. 74b), this refers to the Leviathan and its mate, for He created them male and female, and He slew the female and salted her away for the righteous in the future, for if they would propagate, the world could not exist because of them. הַתַּנִינִם is written. [I.e., the final "yud", which denotes the plural, is missing, hence the implication that the Leviathan did not remain two, but that its number was reduced to one.] – [from Gen. Rabbah 7:4, Midrash Chaseroth V’Yetheroth, Batei Midrashoth, vol 2, p. 225].[22]

In the Talmud Baba Bathra 75 it is told that the Leviathan will be slain and its flesh served as a feast to the righteous in [the] Time to Come and its skin used to cover the tent where the banquet will take place. Those who do not deserve to consume its flesh beneath the tent may receive various vestments of the Leviathan varying from coverings (for the somewhat deserving) to amulets (for the least deserving). The remaining skin of the Leviathan will be spread onto the walls of Jerusalem, thereby illuminating the world with its brightness. The festival of Sukkot (Festival of Booths) therefore concludes with a prayer recited upon leaving the sukkah (booth): "May it be your will, Lord our God and God of our forefathers, that just as I have fulfilled and dwelt in this sukkah, so may I merit in the coming year to dwell in the sukkah of the skin of Leviathan. Next year in Jerusalem."[23]

The enormous size of the Leviathan is described by Johanan bar Nappaha, from whom proceeded nearly all the aggadot concerning this monster: "Once we went in a ship and saw a fish which put his head out of the water. He had horns upon which was written: 'I am one of the meanest creatures that inhabit the sea. I am three hundred miles in length, and enter this day into the jaws of the Leviathan'".[24][21]

When the Leviathan is hungry, reports Rabbi Dimi in the name of Rabbi Johanan, he sends forth from his mouth a heat so great as to make all the waters of the deep boil, and if he would put his head into Paradise no living creature could endure the odor of him.[24] His abode is the Mediterranean Sea; and the waters of the Jordan fall into his mouth.[25][21]

In a legend recorded in the Midrash called Pirke de-Rabbi Eliezer it is stated that the fish which swallowed Jonah narrowly avoided being eaten by the Leviathan, which eats one whale each day.

The body of the Leviathan, especially his eyes, possesses great illuminating power. This was the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer, who, in the course of a voyage in company with Rabbi Joshua, explained to the latter, when frightened by the sudden appearance of a brilliant light, that it probably proceeded from the eyes of the Leviathan. He referred his companion to the words of Job 41:18: "By his neesings a light doth shine, and his eyes are like the eyelids of the morning".[26] However, in spite of his supernatural strength, the leviathan is afraid of a small worm called "kilbit", which clings to the gills of large fish and kills them.[27][21]

In the eleventh-century piyyut (religious poem), Akdamut, recited on Shavuot (Pentecost), it is envisioned that, ultimately, God will slaughter the Leviathan, which is described as having "mighty fins" (and, therefore, a kosher fish, not an inedible snake or crocodile), and it will be served as a sumptuous banquet for all the righteous in Heaven.

In the Zohar, the Leviathan is a metaphor for enlightenment. The Zohar remarks that the legend of the righteous eating the skin of the leviathan at the end of the days is not literal, and merely a metaphor for enlightenment.[28] The Zohar also specifies in detail that the Leviathan has a mate.[29] The Zohar also associates the metaphor of the leviathan with the "tzaddik" or righteous in Zohar 2:11b and 3:58a. The Zohar associates it with the "briach" the pole in the middle of the boards of the tabernacle in Zohar 2:20a. Both, are associated with the Sefira of Yesod.[30]

According to Abraham Isaac Kook, the Leviathan – a singular creature with no mate, "its tail is placed in its mouth" (Zohar) "twisting around and encompassing the entire world" (Rashi on Baba Batra 74b) – projects a vivid metaphor for the universe's underlying unity. This unity will only be revealed in the future, when the righteous will feast on the Leviathan.[31]

Christianity[]

Leviathan can also be used as an image of the devil, endangering both God's creatures—by attempting to eat them—and God's creation—by threatening it with upheaval in the waters of Chaos.[32] A "Dragon" (Drakon), being the usual translation for the Leviathan in the Septuaginta, appears in the Book of Revelation. Although the Old Testament nowhere identifies the Leviathan with the devil, the seven-headed dragon in the Book of Revelation, is.[33] By this the battle between God and the primordial chaos monsters, shifts to a battle between God and the devil.[34] Only once, in the Book of Job, the Leviathan is translated as Sea-Monster (ketos).[35]

In the following chapter, a seven-headed beast, described with the same features as the dragon before, rises from the waters endowing a Beast of the Earth, with power. Dividing the beasts into monster of water and one of dry earth is probably a recalling of the monstrous pair Leviathan and Behemoth.[36] In accordance with Isaiah 27:1, the dragon will be slain by God on the last day and cast into the abyss.[37][38] The annihilation of the chaos-monster results in a new world of peace, without any trace of evil.[39]

St. Thomas Aquinas described Leviathan as the demon of envy, first in punishing the corresponding sinners (Expositio super Iob ad litteram). Peter Binsfeld likewise classified Leviathan as the demon of envy, as one of the seven Princes of Hell corresponding to the seven deadly sins. Leviathan became associated with, and may originally have been referred to by, the visual motif of the Hellmouth, a monstrous animal into whose mouth the damned disappear at the Last Judgement, found in Anglo-Saxon art from about 800, and later all over Europe.[40][41]

The Revised Standard Version of the Bible suggests in a footnote to Job 41:1 that Leviathan may be a name for the crocodile, and in a footnote to Job 40:15, that Behemoth may be a name for the hippopotamus.[42]

Gnosticism[]

The Church Father Origen accused a Gnostic sect of venerating the biblical serpent of the Garden of Eden. Therefore, he calls them Ophites, naming after the serpent they are supposed to worship.[43] In this belief system, the Leviathan appears as an Ouroboros, separating the divine realm from humanity by enveloping or permeating the material world.[44][43][45] We do not know whether or not the Ophites actually identified the serpent of the Garden of Eden with the Leviathan.[43] However, since the Leviathan is basically connoted negatively in this Gnostic cosmology, if they identified him with the serpent of the Book of Genesis, he was probably indeed considered evil and just its advice was good.[46]

According to the cosmology of this Gnostic sect, the world is encapsulated by the Leviathan, in form of a dragon-shaped archon, biting its own tail (ouroboros). Generating the intrinsic evil in the entire universe, the Leviathan separates the lower world, governed by the Archons, from the realm of God.[47] After death, a soul must pass through the seven spheres of the heavens. If the soul does not succeed, it will be swallowed by the Leviathan, who holds the world captive and returns the soul into an animal body.[48]

In Mandaeism, Leviathan is regarded as being coessential with a demon called Ur.[49]

In Manichaeism, an ancient religion influenced by Gnostic ideas, the Leviathan is killed by the sons of the fallen angel Shemyaza. This act is not portrayed as heroic, but as foolish, symbolizing the greatest triumphs as transient, since both are killed by archangels in turn after boasting about their victory. This reflects Manichaean criticism on royal power and advocates asceticism.[50]

Modern usage[]

The word Leviathan has come to refer to any sea monster, and from the early 17th century has also been used to refer to overwhelmingly powerful people or things (comparable to Behemoth or Juggernaut), influentially so by Hobbes' book (1651).[citation needed]

As a term for sea monster, it has also been used of great whales in particular, e.g. in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick - Although in the first Hebrew translation of the novel, translator Elyahu Burtinker chose to translate "Whale" to "Tanin" (intending to refer to another sea monster although in Modern Hebrew usage Tanin more commonly translates to "crocodile"), and leave the word "Leviathan" as it is, nodding to the ambiguity of the word "לויתן" in modern Hebrew – in which the word now simply means "whale".[51]

The Satanic Bible[]

Anton LaVey in The Satanic Bible (1969) has Leviathan representing the element of Water and the direction of west, listing it as one of the Four Crown Princes of Hell. This association was inspired by the demonic hierarchy from The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abra-Melin the Mage. The Church of Satan uses the Hebrew letters at each of the points of the Sigil of Baphomet to represent Leviathan. Starting from the lowest point of the pentagram, and reading counter-clockwise, the word reads "לויתן": (Nun, Tav, Yod, Vav, Lamed) Hebrew for "Leviathan".[52]

See also[]

- Aspidochelone

- Bahamut (This name is thought to derive from the biblical Behemoth.[53])

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- Cetus (mythology)

- Devil Whale

- Falak (Arabian legend)

- Ouroboros

- Rahab (Egypt)

- Ladon (mythology)

References[]

- ^ Cirlot, Juan Eduardo (1971). A Dictionary of Symbols (2nd ed.). Dorset Press. p. 186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilhelm Gesenius, Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (trans.) (1879). Hebrew and Chaldee lexicon to the Old Testament.

- ^ Landes, George M.; Einspahr, Bruce (1978). "Index to Brown, Driver and Briggs Hebrew Lexicon". Journal of Biblical Literature. 97 (1): 108. doi:10.2307/3265844. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 3265844.

- ^ Suchard, Benjamin (24 September 2019). The Development of the Biblical Hebrew Vowels. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004390263. hdl:1887/43120. ISBN 978-90-04-39025-6.

- ^ Schulz, Johann Christoph F. (1792). Io. Christ. Frid. Schulzii ... Scholia in Vetus Testamentum (continuata a G.L. Bauer) (in Latin).

- ^ Uehlinger (1999), p. 514.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Herrmann (1999), p. 133.

- ^ Heider (1999).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Uehlinger (1999), p. 512.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c van der Toorn, K.; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem, eds. (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 512–14. ISBN 9780802824912. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Hermann Gunkel, Heinrich Zimmern; K. William Whitney Jr., trans., Creation And Chaos in the Primeval Era And the Eschaton: A Religio-historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12. (Grand Rapids: MI: Erdmans, 1895, 1921, 2006).

- ^ Enuma Elish, Tablet IV, lines 104–105, 137–138, 144 from Alexander Heidel (1963) [1942], Babylonian Genesis, 41–42.

- ^ Jewish Publication Society translation (1917).

- ^ Gen. 1:21.

- ^ Gen. 1:21 (KJV).

- ^ Ps. 104.

- ^ For example, in Isaiah 27:1.

- ^ Hermann Gunkel, Heinrich Zimmern; K. William Whitney Jr., trans., Creation And Chaos in the Primeval Era And the Eschaton: A Religio-historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12. (Grand Rapids: MI: Erdmans, 1895, 1921, 2006). p. 37-38.

- ^ Watson, R.S. (2005). Chaos Uncreated: A Reassessment of the Theme of "chaos" in the Hebrew Bible. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110179938, ISBN 9783110179934

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, tractate Baba Bathra 74b.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hirsch, Emil G.; Kaufmann Kohler; Solomon Schechter; Isaac Broydé (1901–1906). "Leviathan and Behemoth". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hirsch, Emil G.; Kaufmann Kohler; Solomon Schechter; Isaac Broydé (1901–1906). "Leviathan and Behemoth". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ Chabad. "Rashi's Commentary on Genesis". Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Finkel, Avraham (1993). The Essence of the Holy Days: Insights from the Jewish Sages. Northvale, N.J.: J. Aronson. p. 99. ISBN 0-87668-524-6. OCLC 27935834.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Babylonian Talmud, Baba Bathra 75a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Bekorot 55b; Baba Bathra 75a.

- ^ Bava Batra l.c.

- ^ Shabbat 77b

- ^ Zohar 1:140b. See also Zohar 3:279a

- ^ Zohar 1:4b

- ^ Matuk Midvash on Zohar 2:11b

- ^ Morrison, Chanan; Kook, Abraham Isaac Kook (2013). Sapphire from the Land of Israel: A new light on Weekly Torah Portion from the writings of Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaKohen Kook. p. 91. ISBN 978-1490909363.

- ^ Labriola, Albert C. (1982). "The Medieval View of History in Paradise Lost". In Mulryan, John (ed.). Milton and the Middle Ages. Bucknell University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8387-5036-0.

- ^ Giblett, Rod. Environmental Humanities and the Uncanny: Ecoculture, Literature and Religion. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis, 2019. p. 19

- ^ Wallace, Howard. "Leviathan and the Beast in Revelation." The Biblical Archaeologist 11, no. 3 (1948): 61-68. Accessed September 11, 2021. doi:10.2307/3209231.

- ^ Wallace, Howard. "Leviathan and the Beast in Revelation." The Biblical Archaeologist 11, no. 3 (1948): 61-68. Accessed September 11, 2021. doi:10.2307/3209231.

- ^ Bauckham, R. (1993). The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Vereinigtes Königreich: Cambridge University Press. p. 89

- ^ Wallace, Howard. "Leviathan and the Beast in Revelation." The Biblical Archaeologist 11, no. 3 (1948): 61-68. Accessed September 11, 2021. doi:10.2307/3209231.

- ^ Bauckham, R. (1993). The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Vereinigtes Königreich: Cambridge University Press. p. 89

- ^ Wallace, Howard. "Leviathan and the Beast in Revelation." The Biblical Archaeologist 11, no. 3 (1948): 61-68. Accessed September 11, 2021. doi:10.2307/3209231.

- ^ Link, Luther (1995). The Devil: A Mask Without a Face. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 75–6. ISBN 0-948462-67-1.

- ^ Hofmann, Petra (2008). Infernal Imagery in Anglo-Saxon Charters (Thesis). St Andrews. pp. 143–44. hdl:10023/498.

- ^ The Holy Bible Revised Standard Version. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons. 1959. pp. 555–56.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tuomas Rasimus Paradise Reconsidered in Gnostic Mythmaking: Rethinking Sethianism in Light of the Ophite Evidence BRILL 2009 ISBN 9789047426707 p. 68

- ^ Kurt Rudolph Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism A&C Black 2001 ISBN 9780567086402 p. 69

- ^ April DeConick, Gregory Shaw, John D. Turner Practicing Gnosis: Ritual, Magic, Theurgy and Liturgy in Nag Hammadi, Manichaean and Other Ancient Literature. Essays in Honor of Birger A. Pearson BRILL 2013 ISBN 9789004248526 p. 48

- ^ Tuomas Rasimus Paradise Reconsidered in Gnostic Mythmaking: Rethinking Sethianism in Light of the Ophite Evidence BRILL 2009 ISBN 9789047426707 p. 69

- ^ Silviu Lupaşcu. "In the Ninth Heaven – the Gnostic Background of the Romanian Folklore tradition of the “Heaven’s Custom Houses”". Danubius 1:309-325.

- ^ Tuomas Rasimus Paradise Reconsidered in Gnostic Mythmaking: Rethinking Sethianism in Light of the Ophite Evidence BRILL 2009 ISBN 9789047426707 p. 70

- ^ Hans Jonas: The Gnostic Religion, 3. ed., Boston 2001, p. 117.

- ^ Michel Tardieu Manichaeism University of Illinois Press, 2008 ISBN 9780252032783 p. 46-48

- ^ "לִוְיָתָן". מילוג: המילון העברי החופשי ברשת.

- ^ "The History of the Origin of the Sigil of Baphomet and its Use in the Church of Satan". Church of Satan website. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ Streck, Maximilian (1936), "Ḳāf", The Encyclopaedia of Islām, IV, E. J. Brill ltd., pp. 582–583, ISBN 9004097902

Bibliography[]

- Heider, George C. (1999), "Tannîn", Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 834–836.

- Herrmann, Wolfgang (1999), "Baal", Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 132–139.

- Uehlinger, C. (1999), "Leviathan", Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 511–515.

External links[]

| Look up leviathan in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leviathan. |

- 'Sea monster' whale fossil unearthed. Named Leviathan by scientists 30 June 2010.

- Putting God on Trial – The Biblical Book of Job contains a major section on the literary use of Leviathan.

- Job 41:1–41:34 (KJV)

- The fossilised skull of a colossal "sea monster" has been unearthed along the UK's Jurassic Coast. 27 October 2009

- 'Sea monster' whale fossil unearthed 30 June 2010

- Enuma Elish (Babylonian creation epic)

- Philologos concordance page

- Text of the Leviathan passage from Job 40 and 41

- Leviathan

- Book of Amos

- Book of Isaiah

- Book of Job

- Demons in Gnosticism

- Hebrew words and phrases in the Hebrew Bible

- Sea monsters