Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

In classical mechanics, the Laplace–Runge–Lenz (LRL) vector is a vector used chiefly to describe the shape and orientation of the orbit of one astronomical body around another, such as a binary star or a planet revolving around a star. For two bodies interacting by Newtonian gravity, the LRL vector is a constant of motion, meaning that it is the same no matter where it is calculated on the orbit;[1][2] equivalently, the LRL vector is said to be conserved. More generally, the LRL vector is conserved in all problems in which two bodies interact by a central force that varies as the inverse square of the distance between them; such problems are called Kepler problems.[3][4][5][6]

The hydrogen atom is a Kepler problem, since it comprises two charged particles interacting by Coulomb's law of electrostatics, another inverse-square central force. The LRL vector was essential in the first quantum mechanical derivation of the spectrum of the hydrogen atom,[7][8] before the development of the Schrödinger equation. However, this approach is rarely used today.

In classical and quantum mechanics, conserved quantities generally correspond to a symmetry of the system.[9] The conservation of the LRL vector corresponds to an unusual symmetry; the Kepler problem is mathematically equivalent to a particle moving freely on the surface of a four-dimensional (hyper-)sphere,[10] so that the whole problem is symmetric under certain rotations of the four-dimensional space.[11] This higher symmetry results from two properties of the Kepler problem: the velocity vector always moves in a perfect circle and, for a given total energy, all such velocity circles intersect each other in the same two points.[12]

The Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector is named after Pierre-Simon de Laplace, Carl Runge and Wilhelm Lenz. It is also known as the Laplace vector,[13][14] the Runge–Lenz vector[15] and the Lenz vector.[8] Ironically, none of those scientists discovered it.[15] The LRL vector has been re-discovered and re-formulated several times;[15] for example, it is equivalent to the dimensionless eccentricity vector of celestial mechanics.[2][14][16] Various generalizations of the LRL vector have been defined, which incorporate the effects of special relativity, electromagnetic fields and even different types of central forces.[17][18][19]

Context[]

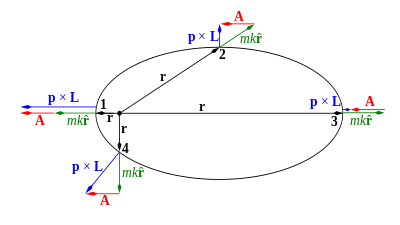

A single particle moving under any conservative central force has at least four constants of motion: the total energy E and the three Cartesian components of the angular momentum vector L with respect to the center of force.[20][21] The particle's orbit is confined to the plane defined by the particle's initial momentum p (or, equivalently, its velocity v) and the vector r between the particle and the center of force[20][21] (see Figure 1). This plane of motion is perpendicular to the constant angular momentum vector L = r × p; this may be expressed mathematically by the vector dot product equation r ⋅ L = 0. Given its mathematical definition below, the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector (LRL vector) A is always perpendicular to the constant angular momentum vector L for all central forces (A ⋅ L = 0). Therefore A always lies in the plane of motion. As shown below, A points from the center of force to the periapsis of the motion, the point of closest approach, and its length is proportional to the eccentricity of the orbit.[1]

The LRL vector A is constant in length and direction, but only for an inverse-square central force.[1] For other central forces, the vector A is not constant, but changes in both length and direction. If the central force is approximately an inverse-square law, the vector A is approximately constant in length, but slowly rotates its direction.[14] A generalized conserved LRL vector can be defined for all central forces, but this generalized vector is a complicated function of position, and usually not expressible in closed form.[18][19]

The LRL vector differs from other conserved quantities in the following property. Whereas for typical conserved quantities, there is a corresponding cyclic coordinate in the three-dimensional Lagrangian of the system, there does not exist such a coordinate for the LRL vector. Thus, the conservation of the LRL vector must be derived directly, e.g., by the method of Poisson brackets, as described below. Conserved quantities of this kind are called "dynamic", in contrast to the usual "geometric" conservation laws, e.g., that of the angular momentum.

History of rediscovery[]

The LRL vector A is a constant of motion of the Kepler problem, and is useful in describing astronomical orbits, such as the motion of planets and binary stars. Nevertheless, it has never been well-known among physicists, possibly because it is less intuitive than momentum and angular momentum. Consequently, it has been rediscovered independently several times over the last three centuries.[15]

Jakob Hermann was the first to show that A is conserved for a special case of the inverse-square central force,[22] and worked out its connection to the eccentricity of the orbital ellipse. Hermann's work was generalized to its modern form by Johann Bernoulli in 1710.[23] At the end of the century, Pierre-Simon de Laplace rediscovered the conservation of A, deriving it analytically, rather than geometrically.[24] In the middle of the nineteenth century, William Rowan Hamilton derived the equivalent eccentricity vector defined below,[16] using it to show that the momentum vector p moves on a circle for motion under an inverse-square central force (Figure 3).[12]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Josiah Willard Gibbs derived the same vector by vector analysis.[25] Gibbs' derivation was used as an example by Carl Runge in a popular German textbook on vectors,[26] which was referenced by Wilhelm Lenz in his paper on the (old) quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom.[27] In 1926, Wolfgang Pauli used the LRL vector to derive the energy levels of the hydrogen atom using the matrix mechanics formulation of quantum mechanics,[7] after which it became known mainly as the Runge–Lenz vector.[15]

Mathematical definition[]

An inverse-square central force acting on a single particle is described by the equation

The corresponding potential energy is given by . The constant parameter k describes the strength of the central force; it is equal to G⋅M⋅m for gravitational and −ke⋅Q⋅q for electrostatic forces. The force is attractive if k > 0 and repulsive if k < 0.

The LRL vector A is defined mathematically by the formula[1]

where

- m is the mass of the point particle moving under the central force,

- p is its momentum vector,

- L = r × p is its angular momentum vector,

- r is the position vector of the particle (Figure 1),

- is the corresponding unit vector, i.e., , and

- r is the magnitude of r, the distance of the mass from the center of force.

The SI units of the LRL vector are joule-kilogram-meter (J⋅kg⋅m). This follows because the units of p and L are kg⋅m/s and J⋅s, respectively. This agrees with the units of m (kg) and of k (N⋅m2).

This definition of the LRL vector A pertains to a single point particle of mass m moving under the action of a fixed force. However, the same definition may be extended to two-body problems such as the Kepler problem, by taking m as the reduced mass of the two bodies and r as the vector between the two bodies.

Since the assumed force is conservative, the total energy E is a constant of motion,

The assumed force is also a central force. Hence, the angular momentum vector L is also conserved and defines the plane in which the particle travels. The LRL vector A is perpendicular to the angular momentum vector L because both p × L and r are perpendicular to L. It follows that A lies in the plane of motion.

Alternative formulations for the same constant of motion may be defined, typically by scaling the vector with constants, such as the mass m, the force parameter k or the angular momentum L.[15] The most common variant is to divide A by mk, which yields the eccentricity vector, [2][16] a dimensionless vector along the semi-major axis whose modulus equals the eccentricity of the conic:

An equivalent formulation[14] multiplies this eccentricity vector by the major semiaxis a, giving the resulting vector the units of length. Yet another formulation[28] divides A by , yielding an equivalent conserved quantity with units of inverse length, a quantity that appears in the solution of the Kepler problem

where is the angle between A and the position vector r. Further alternative formulations are given below.

Derivation of the Kepler orbits[]

The shape and orientation of the orbits can be determined from the LRL vector as follows.[1] Taking the dot product of A with the position vector r gives the equation

where θ is the angle between r and A (Figure 2). Permuting the scalar triple product yields

Rearranging yields the solution for the Kepler equation

This corresponds to the formula for a conic section of eccentricity e

where the eccentricity and C is a constant.[1]

Taking the dot product of A with itself yields an equation involving the total energy E,[1]

which may be rewritten in terms of the eccentricity,[1]

Thus, if the energy E is negative (bound orbits), the eccentricity is less than one and the orbit is an ellipse. Conversely, if the energy is positive (unbound orbits, also called "scattered orbits"[1]), the eccentricity is greater than one and the orbit is a hyperbola.[1] Finally, if the energy is exactly zero, the eccentricity is one and the orbit is a parabola.[1] In all cases, the direction of A lies along the symmetry axis of the conic section and points from the center of force toward the periapsis, the point of closest approach.[1]

Circular momentum hodographs[]

The conservation of the LRL vector A and angular momentum vector L is useful in showing that the momentum vector p moves on a circle under an inverse-square central force.[12][15]

Taking the dot product of

with itself yields

Further choosing L along the z-axis, and the major semiaxis as the x-axis, yields the locus equation for p,

In other words, the momentum vector p is confined to a circle of radius mk/L = L/ℓ centered on (0, A/L).[29] The eccentricity e corresponds to the cosine of the angle η shown in Figure 3.

In the degenerate limit of circular orbits, and thus vanishing A, the circle centers at the origin (0,0). For brevity, it is also useful to introduce the variable .

This circular hodograph is useful in illustrating the symmetry of the Kepler problem.

Constants of motion and superintegrability[]

The seven scalar quantities E, A and L (being vectors, the latter two contribute three conserved quantities each) are related by two equations, A ⋅ L = 0 and A2 = m2k2 + 2 mEL2, giving five independent constants of motion. (Since the magnitude of A, hence the eccentricity e of the orbit, can be determined from the total angular momentum L and the energy E, only the direction of A is conserved independently; moreover, since A must be perpendicular to L, it contributes only one additional conserved quantity.)

This is consistent with the six initial conditions (the particle's initial position and velocity vectors, each with three components) that specify the orbit of the particle, since the initial time is not determined by a constant of motion. The resulting 1-dimensional orbit in 6-dimensional phase space is thus completely specified.

A mechanical system with d degrees of freedom can have at most 2d − 1 constants of motion, since there are 2d initial conditions and the initial time cannot be determined by a constant of motion. A system with more than d constants of motion is called superintegrable and a system with 2d − 1 constants is called maximally superintegrable.[30] Since the solution of the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in one coordinate system can yield only d constants of motion, superintegrable systems must be separable in more than one coordinate system.[31] The Kepler problem is maximally superintegrable, since it has three degrees of freedom (d = 3) and five independent constant of motion; its Hamilton–Jacobi equation is separable in both spherical coordinates and parabolic coordinates,[17] as described below.

Maximally superintegrable systems follow closed, one-dimensional orbits in phase space, since the orbit is the intersection of the phase-space isosurfaces of their constants of motion. Consequently, the orbits are perpendicular to all gradients of all these independent isosurfaces, five in this specific problem, and hence are determined by the generalized cross products of all of these gradients. As a result, all superintegrable systems are automatically describable by Nambu mechanics,[32] alternatively, and equivalently, to Hamiltonian mechanics.

Maximally superintegrable systems can be quantized using commutation relations, as illustrated below.[33] Nevertheless, equivalently, they are also quantized in the Nambu framework, such as this classical Kepler problem into the quantum hydrogen atom.[34]

Evolution under perturbed potentials[]

The Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector A is conserved only for a perfect inverse-square central force. In most practical problems such as planetary motion, however, the interaction potential energy between two bodies is not exactly an inverse square law, but may include an additional central force, a so-called perturbation described by a potential energy h(r). In such cases, the LRL vector rotates slowly in the plane of the orbit, corresponding to a slow apsidal precession of the orbit.

By assumption, the perturbing potential h(r) is a conservative central force, which implies that the total energy E and angular momentum vector L are conserved. Thus, the motion still lies in a plane perpendicular to L and the magnitude A is conserved, from the equation A2 = m2k2 + 2mEL2. The perturbation potential h(r) may be any sort of function, but should be significantly weaker than the main inverse-square force between the two bodies.

The rate at which the LRL vector rotates provides information about the perturbing potential h(r). Using canonical perturbation theory and action-angle coordinates, it is straightforward to show[1] that A rotates at a rate of,

where T is the orbital period, and the identity L dt = m r2 dθ was used to convert the time integral into an angular integral (Figure 5). The expression in angular brackets, ⟨h(r)⟩, represents the perturbing potential, but averaged over one full period; that is, averaged over one full passage of the body around its orbit. Mathematically, this time average corresponds to the following quantity in curly braces. This averaging helps to suppress fluctuations in the rate of rotation.

This approach was used to help verify Einstein's theory of general relativity, which adds a small effective inverse-cubic perturbation to the normal Newtonian gravitational potential,[35]

Inserting this function into the integral and using the equation

to express r in terms of θ, the precession rate of the periapsis caused by this non-Newtonian perturbation is calculated to be[35]

which closely matches the observed anomalous precession of Mercury[36] and binary pulsars.[37] This agreement with experiment is strong evidence for general relativity.[38][39]

Poisson brackets[]

The unscaled functions[]

The algebraic structure of the problem is, as explained in later sections, SO(4)/ℤ2 ~ SO(3) × SO(3).[11] The three components Li of the angular momentum vector L have the Poisson brackets[1]

where i=1,2,3 and ϵijs is the fully antisymmetric tensor, i.e., the Levi-Civita symbol; the summation index s is used here to avoid confusion with the force parameter k defined above. Then since the LRL vector A transforms like a vector, we have the following Poisson bracket relations between A and L:[40]

Finally, the Poisson bracket relations between the different components of A are as follows:[41]

where is the Hamiltonian. Note that the span of the components of A and the components of L is not closed under Poisson brackets, because of the factor of on the right-hand side of this last relation.

Finally, since both L and A are constants of motion, we have

The Poisson brackets will be extended to quantum mechanical commutation relations in the next section and to Lie brackets in a following section.

The scaled functions[]

As noted below, a scaled Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector D may be defined with the same units as angular momentum by dividing A by . Since D still transforms like a vector, the Poisson brackets of D with the angular momentum vector L can then be written in a similar form[11][8]

The Poisson brackets of D with itself depend on the sign of H, i.e., on whether the energy is negative (producing closed, elliptical orbits under an inverse-square central force) or positive (producing open, hyperbolic orbits under an inverse-square central force). For negative energies—i.e., for bound systems—the Poisson brackets are[42]

We may now appreciate the motivation for the chosen scaling of D: With this scaling, the Hamiltonian no longer appears on the right-hand side of the preceding relation. Thus, the span of the three components of L and the three components of D forms a six-dimensional Lie algebra under the Poisson bracket. This Lie algebra is isomorphic to so(4), the Lie algebra of the 4-dimensional rotation group SO(4).[43]

By contrast, for positive energy, the Poisson brackets have the opposite sign,

In this case, the Lie algebra is isomorphic to so(3,1).

The distinction between positive and negative energies arises because the desired scaling—the one that eliminates the Hamiltonian from the right-hand side of the Poisson bracket relations between the components of the scaled LRL vector—involves the square root of the Hamiltonian. To obtain real-valued functions, we must then take the absolute value of the Hamiltonian, which distinguishes between positive values (where ) and negative values (where ).

Casimir invariants and the energy levels[]

The Casimir invariants for negative energies are

and have vanishing Poisson brackets with all components of D and L,

C2 is trivially zero, since the two vectors are always perpendicular.

However, the other invariant, C1, is non-trivial and depends only on m, k and E. Upon canonical quantization, this invariant allows the energy levels of hydrogen-like atoms to be derived using only quantum mechanical canonical commutation relations, instead of the conventional solution of the Schrödinger equation.[8][43] This derivation is discussed in detail in the next section.

Quantum mechanics of the hydrogen atom[]

Poisson brackets provide a simple guide for quantizing most classical systems: the commutation relation of two quantum mechanical operators is specified by the Poisson bracket of the corresponding classical variables, multiplied by iħ.[44]

By carrying out this quantization and calculating the eigenvalues of the C1 Casimir operator for the Kepler problem, Wolfgang Pauli was able to derive the energy levels of hydrogen-like atoms (Figure 6) and, thus, their atomic emission spectrum.[7] This elegant 1926 derivation was obtained before the development of the Schrödinger equation.[45]

A subtlety of the quantum mechanical operator for the LRL vector A is that the momentum and angular momentum operators do not commute; hence, the quantum operator cross product of p and L must be defined carefully.[8] Typically, the operators for the Cartesian components As are defined using a symmetrized (Hermitian) product,

Once this is done, one can show that the quantum LRL operators satisfy commutations relations exactly analogous to the Poisson bracket relations in the previous section—just replacing the Poisson bracket with times the commutator.[46][47]

From these operators, additional ladder operators for L can be defined,

These further connect different eigenstates of L2, so different spin multiplets, among themselves.

A normalized first Casimir invariant operator, quantum analog of the above, can likewise be defined,

where H−1 is the inverse of the Hamiltonian energy operator, and I is the identity operator.

Applying these ladder operators to the eigenstates |ℓmn〉 of the total angular momentum, azimuthal angular momentum and energy operators, the eigenvalues of the first Casimir operator, C1, are seen to be quantized, n2 − 1. Importantly, by dint of the vanishing of C2, they are independent of the ℓ and m quantum numbers, making the energy levels degenerate.[8]

Hence, the energy levels are given by

which coincides with the Rydberg formula for hydrogen-like atoms (Figure 6). The additional symmetry operators A have connected the different ℓ multiplets among themselves, for a given energy (and C1), dictating n2 states at each level. In effect, they have enlarged the angular momentum group SO(3) to SO(4)/ℤ2 ~ SO(3) × SO(3).[48]

Conservation and symmetry[]

The conservation of the LRL vector corresponds to a subtle symmetry of the system. In classical mechanics, symmetries are continuous operations that map one orbit onto another without changing the energy of the system; in quantum mechanics, symmetries are continuous operations that "mix" electronic orbitals of the same energy, i.e., degenerate energy levels. A conserved quantity is usually associated with such symmetries.[1] For example, every central force is symmetric under the rotation group SO(3), leading to the conservation of the angular momentum L. Classically, an overall rotation of the system does not affect the energy of an orbit; quantum mechanically, rotations mix the spherical harmonics of the same quantum number l without changing the energy.

The symmetry for the inverse-square central force is higher and more subtle. The peculiar symmetry of the Kepler problem results in the conservation of both the angular momentum vector L and the LRL vector A (as defined above) and, quantum mechanically, ensures that the energy levels of hydrogen do not depend on the angular momentum quantum numbers l and m. The symmetry is more subtle, however, because the symmetry operation must take place in a higher-dimensional space; such symmetries are often called "hidden symmetries".[49]

Classically, the higher symmetry of the Kepler problem allows for continuous alterations of the orbits that preserve energy but not angular momentum; expressed another way, orbits of the same energy but different angular momentum (eccentricity) can be transformed continuously into one another. Quantum mechanically, this corresponds to mixing orbitals that differ in the l and m quantum numbers, such as the s (l = 0) and p (l = 1) atomic orbitals. Such mixing cannot be done with ordinary three-dimensional translations or rotations, but is equivalent to a rotation in a higher dimension.

For negative energies – i.e., for bound systems – the higher symmetry group is SO(4), which preserves the length of four-dimensional vectors

In 1935, Vladimir Fock showed that the quantum mechanical bound Kepler problem is equivalent to the problem of a free particle confined to a three-dimensional unit sphere in four-dimensional space.[10] Specifically, Fock showed that the Schrödinger wavefunction in the momentum space for the Kepler problem was the stereographic projection of the spherical harmonics on the sphere. Rotation of the sphere and re-projection results in a continuous mapping of the elliptical orbits without changing the energy, an SO(4) symmetry sometimes known as Fock symmetry;[50] quantum mechanically, this corresponds to a mixing of all orbitals of the same energy quantum number n. Valentine Bargmann noted subsequently that the Poisson brackets for the angular momentum vector L and the scaled LRL vector A formed the Lie algebra for SO(4).[11][42] Simply put, the six quantities A and L correspond to the six conserved angular momenta in four dimensions, associated with the six possible simple rotations in that space (there are six ways of choosing two axes from four). This conclusion does not imply that our universe is a three-dimensional sphere; it merely means that this particular physics problem (the two-body problem for inverse-square central forces) is mathematically equivalent to a free particle on a three-dimensional sphere.

For positive energies – i.e., for unbound, "scattered" systems – the higher symmetry group is SO(3,1), which preserves the Minkowski length of 4-vectors

Both the negative- and positive-energy cases were considered by Fock[10] and Bargmann[11] and have been reviewed encyclopedically by Bander and Itzykson.[51][52]

The orbits of central-force systems – and those of the Kepler problem in particular – are also symmetric under reflection. Therefore, the SO(3), SO(4) and SO(3,1) groups cited above are not the full symmetry groups of their orbits; the full groups are O(3), O(4), and O(3,1), respectively. Nevertheless, only the connected subgroups, SO(3), SO(4) and SO(3,1), are needed to demonstrate the conservation of the angular momentum and LRL vectors; the reflection symmetry is irrelevant for conservation, which may be derived from the Lie algebra of the group.

Rotational symmetry in four dimensions[]

The connection between the Kepler problem and four-dimensional rotational symmetry SO(4) can be readily visualized.[51][53][54] Let the four-dimensional Cartesian coordinates be denoted (w, x, y, z) where (x, y, z) represent the Cartesian coordinates of the normal position vector r. The three-dimensional momentum vector p is associated with a four-dimensional vector on a three-dimensional unit sphere

where is the unit vector along the new w axis. The transformation mapping p to η can be uniquely inverted; for example, the x component of the momentum equals

and similarly for py and pz. In other words, the three-dimensional vector p is a stereographic projection of the four-dimensional vector, scaled by p0 (Figure 8).

Without loss of generality, we may eliminate the normal rotational symmetry by choosing the Cartesian coordinates such that the z axis is aligned with the angular momentum vector L and the momentum hodographs are aligned as they are in Figure 7, with the centers of the circles on the y axis. Since the motion is planar, and p and L are perpendicular, pz = ηz = 0 and attention may be restricted to the three-dimensional vector = (ηw, ηx, ηy). The family of Apollonian circles of momentum hodographs (Figure 7) correspond to a family of great circles on the three-dimensional sphere, all of which intersect the ηx axis at the two foci ηx = ±1, corresponding to the momentum hodograph foci at px = ±p0. These great circles are related by a simple rotation about the ηx-axis (Figure 8). This rotational symmetry transforms all the orbits of the same energy into one another; however, such a rotation is orthogonal to the usual three-dimensional rotations, since it transforms the fourth dimension ηw. This higher symmetry is characteristic of the Kepler problem and corresponds to the conservation of the LRL vector.

An elegant action-angle variables solution for the Kepler problem can be obtained by eliminating the redundant four-dimensional coordinates in favor of elliptic cylindrical coordinates (χ, ψ, φ)[55]

where sn, cn and dn are Jacobi's elliptic functions.

Generalizations to other potentials and relativity[]

The Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector can also be generalized to identify conserved quantities that apply to other situations.

In the presence of a uniform electric field E, the generalized Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector is[17][56]

where q is the charge of the orbiting particle. Although is not conserved, it gives rise to a conserved quantity, namely .

Further generalizing the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector to other potentials and special relativity, the most general form can be written as[18]

where u = 1/r and ξ = cos θ, with the angle θ defined by

and γ is the Lorentz factor. As before, we may obtain a conserved binormal vector B by taking the cross product with the conserved angular momentum vector

These two vectors may likewise be combined into a conserved dyadic tensor W,

In illustration, the LRL vector for a non-relativistic, isotropic harmonic oscillator can be calculated.[18] Since the force is central,

the angular momentum vector is conserved and the motion lies in a plane.

The conserved dyadic tensor can be written in a simple form

although p and r are not necessarily perpendicular.

The corresponding Runge–Lenz vector is more complicated,

where

is the natural oscillation frequency, and

Proofs that the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector is conserved in Kepler problems[]

The following are arguments showing that the LRL vector is conserved under central forces that obey an inverse-square law.

Direct proof of conservation[]

A central force acting on the particle is

for some function of the radius . Since the angular momentum is conserved under central forces, and

where the momentum and where the triple cross product has been simplified using Lagrange's formula

The identity

yields the equation

For the special case of an inverse-square central force , this equals

Therefore, A is conserved for inverse-square central forces[57]

A shorter proof is obtained by using the relation of angular momentum to angular velocity, , which holds for a particle traveling in a plane perpendicular to . Specifying to inverse-square central forces, the time derivative of is

where the last equality holds because a unit vector can only change by rotation, and is the orbital velocity of the rotating vector. Thus, A is seen to be a difference of two vectors with equal time derivatives.

As described elsewhere in this article, this LRL vector A is a special case of a general conserved vector that can be defined for all central forces.[18][19] However, since most central forces do not produce closed orbits (see Bertrand's theorem), the analogous vector rarely has a simple definition and is generally a multivalued function of the angle θ between r and .

Hamilton–Jacobi equation in parabolic coordinates[]

The constancy of the LRL vector can also be derived from the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in parabolic coordinates (ξ, η), which are defined by the equations

where r represents the radius in the plane of the orbit

The inversion of these coordinates is

Separation of the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in these coordinates yields the two equivalent equations[17][58]

where Γ is a constant of motion. Subtraction and re-expression in terms of the Cartesian momenta px and py shows that Γ is equivalent to the LRL vector

Noether's theorem[]

The connection between the rotational symmetry described above and the conservation of the LRL vector can be made quantitative by way of Noether's theorem. This theorem, which is used for finding constants of motion, states that any infinitesimal variation of the generalized coordinates of a physical system

that causes the Lagrangian to vary to first order by a total time derivative

corresponds to a conserved quantity Γ

In particular, the conserved LRL vector component As corresponds to the variation in the coordinates[59]

where i equals 1, 2 and 3, with xi and pi being the ith components of the position and momentum vectors r and p, respectively; as usual, δis represents the Kronecker delta. The resulting first-order change in the Lagrangian is

Substitution into the general formula for the conserved quantity Γ yields the conserved component As of the LRL vector,

Lie transformation[]

The Noether theorem derivation of the conservation of the LRL vector A is elegant, but has one drawback: the coordinate variation δxi involves not only the position r, but also the momentum p or, equivalently, the velocity v.[60] This drawback may be eliminated by instead deriving the conservation of A using an approach pioneered by Sophus Lie.[61][62] Specifically, one may define a Lie transformation[49] in which the coordinates r and the time t are scaled by different powers of a parameter λ (Figure 9),

This transformation changes the total angular momentum L and energy E,

but preserves their product EL2. Therefore, the eccentricity e and the magnitude A are preserved, as may be seen from the equation for A2

The direction of A is preserved as well, since the semiaxes are not altered by a global scaling. This transformation also preserves Kepler's third law, namely, that the semiaxis a and the period T form a constant T2/a3.

Alternative scalings, symbols and formulations[]

Unlike the momentum and angular momentum vectors p and L, there is no universally accepted definition of the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector; several different scaling factors and symbols are used in the scientific literature. The most common definition is given above, but another common alternative is to divide by the constant mk to obtain a dimensionless conserved eccentricity vector

where v is the velocity vector. This scaled vector e has the same direction as A and its magnitude equals the eccentricity of the orbit, and thus vanishes for circular orbits.

Other scaled versions are also possible, e.g., by dividing A by m alone

or by p0

which has the same units as the angular momentum vector L.

In rare cases, the sign of the LRL vector may be reversed, i.e., scaled by −1. Other common symbols for the LRL vector include a, R, F, J and V. However, the choice of scaling and symbol for the LRL vector do not affect its conservation.

An alternative conserved vector is the binormal vector B studied by William Rowan Hamilton,[16]

which is conserved and points along the minor semiaxis of the ellipse. (It is not defined for vanishing eccentricity.)

The LRL vector A = B × L is the cross product of B and L (Figure 4). On the momentum hodograph in the relevant section above, B is readily seen to connect the origin of momenta with the center of the circular hodograph, and to possess magnitude A/L. At perihelion, it points in the direction of the momentum.

The vector B is denoted as "binormal" since it is perpendicular to both A and L. Similar to the LRL vector itself, the binormal vector can be defined with different scalings and symbols.

The two conserved vectors, A and B can be combined to form a conserved dyadic tensor W,[18]

where α and β are arbitrary scaling constants and represents the tensor product (which is not related to the vector cross product, despite their similar symbol). Written in explicit components, this equation reads

Being perpendicular to each another, the vectors A and B can be viewed as the principal axes of the conserved tensor W, i.e., its scaled eigenvectors. W is perpendicular to L ,

since A and B are both perpendicular to L as well, L ⋅ A = L ⋅ B = 0.

More directly, this equation reads, in explicit components,

See also[]

- Astrodynamics: Orbit, Eccentricity vector, Orbital elements

- Bertrand's theorem

- Binet equation

- Two-body problem

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Goldstein, H. (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 102–105, 421–422.

- ^ a b c Taff, L. G. (1985). Celestial Mechanics: A Computational Guide for the Practitioner. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 42–43.

- ^ Goldstein, H. (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 94–102.

- ^ Arnold, V. I. (1989). Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 38. ISBN 0-387-96890-3.

- ^ Sommerfeld, A. (1964). Mechanics. Lectures on Theoretical Physics. Vol. 1. Translated by Martin O. Stern (4th ed.). New York: Academic Press. pp. 38–45.

- ^ Lanczos, C. (1970). The Variational Principles of Mechanics (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 118, 129, 242, 248.

- ^ a b c Pauli, W. (1926). "Über das Wasserstoffspektrum vom Standpunkt der neuen Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik. 36 (5): 336–363. Bibcode:1926ZPhy...36..336P. doi:10.1007/BF01450175. S2CID 128132824.

- ^ a b c d e f Bohm, A. (1993). Quantum Mechanics: Foundations and Applications (3rd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 205–222.

- ^ Hanca, J.; Tulejab, S.; Hancova, M. (2004). "Symmetries and conservation laws: Consequences of Noether's theorem". American Journal of Physics. 72 (4): 428–35. Bibcode:2004AmJPh..72..428H. doi:10.1119/1.1591764.

- ^ a b c Fock, V. (1935). "Zur Theorie des Wasserstoffatoms". Zeitschrift für Physik. 98 (3–4): 145–154. Bibcode:1935ZPhy...98..145F. doi:10.1007/BF01336904. S2CID 123112334.

- ^ a b c d e Bargmann, V. (1936). "Zur Theorie des Wasserstoffatoms: Bemerkungen zur gleichnamigen Arbeit von V. Fock". Zeitschrift für Physik. 99 (7–8): 576–582. Bibcode:1936ZPhy...99..576B. doi:10.1007/BF01338811. S2CID 117461194.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, W. R. (1847). "The hodograph or a new method of expressing in symbolic language the Newtonian law of attraction". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 3: 344–353.

- ^ Goldstein, H. (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 421.

- ^ a b c d Arnold, V. I. (1989). Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 413–415]. ISBN 0-387-96890-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Goldstein, H. (1975). "Prehistory of the Runge–Lenz vector". American Journal of Physics. 43 (8): 737–738. Bibcode:1975AmJPh..43..737G. doi:10.1119/1.9745.

Goldstein, H. (1976). "More on the prehistory of the Runge–Lenz vector". American Journal of Physics. 44 (11): 1123–1124. Bibcode:1976AmJPh..44.1123G. doi:10.1119/1.10202. - ^ a b c d Hamilton, W. R. (1847). "Applications of Quaternions to Some Dynamical Questions". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 3: Appendix III.

- ^ a b c d Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz E. M. (1976). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Pergamon Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-08-021022-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Fradkin, D. M. (1967). "Existence of the Dynamic Symmetries O4 and SU3 for All Classical Central Potential Problems". Progress of Theoretical Physics. 37 (5): 798–812. Bibcode:1967PThPh..37..798F. doi:10.1143/PTP.37.798.

- ^ a b c Yoshida, T. (1987). "Two methods of generalisation of the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector". European Journal of Physics. 8 (4): 258–259. Bibcode:1987EJPh....8..258Y. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/8/4/005.

- ^ a b Goldstein, H. (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 1–11.

- ^ a b Symon, K. R. (1971). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 103–109, 115–128.

- ^ Hermann, J. (1710). "Metodo d'investigare l'Orbite de' Pianeti, nell' ipotesi che le forze centrali o pure le gravità degli stessi Pianeti sono in ragione reciproca de' quadrati delle distanze, che i medesimi tengono dal Centro, a cui si dirigono le forze stesse". Giornale de Letterati d'Italia. 2: 447–467.

Hermann, J. (1710). "Extrait d'une lettre de M. Herman à M. Bernoulli datée de Padoüe le 12. Juillet 1710". Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (Paris). 1732: 519–521. - ^ Bernoulli, J. (1710). "Extrait de la Réponse de M. Bernoulli à M. Herman datée de Basle le 7. Octobre 1710". Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (Paris). 1732: 521–544.

- ^ Laplace, P. S. (1799). Traité de mécanique celeste. Paris, Duprat. Tome I, Premiere Partie, Livre II, pp.165ff.

- ^ Gibbs, J. W.; Wilson E. B. (1901). Vector Analysis. New York: Scribners. p. 135.

- ^ Runge, C. (1919). Vektoranalysis. Vol. I. Leipzig: Hirzel.

- ^ Lenz, W. (1924). "Über den Bewegungsverlauf und Quantenzustände der gestörten Keplerbewegung". Zeitschrift für Physik. 24 (1): 197–207. Bibcode:1924ZPhy...24..197L. doi:10.1007/BF01327245. S2CID 121552327.

- ^ Symon, K. R. (1971). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 130–131.

- ^ The conserved binormal Hamilton vector on this momentum plane (pink) has a simpler geometrical significance, and may actually supplant it, as , see Patera, R. P. (1981). "Momentum-space derivation of the Runge-Lenz vector", Am. J. Phys 49 593–594. It has length A/L and is discussed in section #Alternative scalings, symbols and formulations.

- ^ Evans, N. W. (1990). "Superintegrability in classical mechanics". Physical Review A. 41 (10): 5666–5676. Bibcode:1990PhRvA..41.5666E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.41.5666. PMID 9902953.

- ^ Sommerfeld, A. (1923). Atomic Structure and Spectral Lines. London: Methuen. p. 118.

- ^ Curtright, T.; Zachos C. (2003). "Classical and Quantum Nambu Mechanics". Physical Review. D68 (8): 085001. arXiv:hep-th/0212267. Bibcode:2003PhRvD..68h5001C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.68.085001. S2CID 17388447.

- ^ Evans, N. W. (1991). "Group theory of the Smorodinsky–Winternitz system". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 32 (12): 3369–3375. Bibcode:1991JMP....32.3369E. doi:10.1063/1.529449.

- ^ Zachos, C.; Curtright T. (2004). "Branes, quantum Nambu brackets, and the hydrogen atom". Czech Journal of Physics. 54 (11): 1393–1398. arXiv:math-ph/0408012. Bibcode:2004CzJPh..54.1393Z. doi:10.1007/s10582-004-9807-x. S2CID 14074249.

- ^ a b Einstein, A. (1915). "Erklärung der Perihelbewegung des Merkur aus der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie". Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 1915: 831–839. Bibcode:1915SPAW.......831E.

- ^ Le Verrier, U. J. J. (1859). "Lettre de M. Le Verrier à M. Faye sur la Théorie de Mercure et sur le Mouvement du Périhélie de cette Planète". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris. 49: 379–383.

- ^ Will, C. M. (1979). General Relativity, an Einstein Century Survey (SW Hawking and W Israel ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2.

- ^ Pais, A. (1982). Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Roseveare, N. T. (1982). Mercury's Perihelion from Le Verrier to Einstein. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-858174-1.

- ^ Hall 2013 Proposition 17.25.

- ^ Hall 2013 Proposition 18.7; note that Hall uses a different normalization of the LRL vector.

- ^ a b Hall 2013 Theorem 18.9.

- ^ a b Hall 2013 Section 18.4.4.

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (1958). Principles of Quantum Mechanics (4th revised ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Schrödinger, E. (1926). "Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem". Annalen der Physik. 384 (4): 361–376. Bibcode:1926AnP...384..361S. doi:10.1002/andp.19263840404.

- ^ Hall 2013 Proposition 18.12.

- ^ Merzbacher, Eugen (1998-01-07). Quantum Mechanics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 268–270. ISBN 978-0-471-88702-7.

- ^ Hall 2013 Theorem 18.14.

- ^ a b Prince, G. E.; Eliezer C. J. (1981). "On the Lie symmetries of the classical Kepler problem". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General. 14 (3): 587–596. Bibcode:1981JPhA...14..587P. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/14/3/009.

- ^ Nikitin, A G (7 December 2012). "New exactly solvable systems with Fock symmetry". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical. 45 (48): 485204. arXiv:1205.3094. Bibcode:2012JPhA...45V5204N. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/45/48/485204. S2CID 119138270.

- ^ a b Bander, M.; Itzykson C. (1966). "Group Theory and the Hydrogen Atom (I)". Reviews of Modern Physics. 38 (2): 330–345. Bibcode:1966RvMP...38..330B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.38.330.

- ^ Bander, M.; Itzykson C. (1966). "Group Theory and the Hydrogen Atom (II)". Reviews of Modern Physics. 38 (2): 346–358. Bibcode:1966RvMP...38..346B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.38.346.

- ^ Rogers, H. H. (1973). "Symmetry transformations of the classical Kepler problem". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 14 (8): 1125–1129. Bibcode:1973JMP....14.1125R. doi:10.1063/1.1666448.

- ^ Guillemin, V.; Sternberg S. (1990). Variations on a Theme by Kepler. Vol. 42. American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications. ISBN 0-8218-1042-1.

- ^ Lakshmanan, M.; Hasegawa H. (1984). "On the canonical equivalence of the Kepler problem in coordinate and momentum spaces". Journal of Physics A. 17 (16): L889–L893. Bibcode:1984JPhA...17L.889L. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/17/16/006.

- ^ Redmond, P. J. (1964). "Generalization of the Runge–Lenz Vector in the Presence of an Electric Field". Physical Review. 133 (5B): B1352–B1353. Bibcode:1964PhRv..133.1352R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.133.B1352.

- ^ Hall 2013 Proposition 2.34.

- ^ Dulock, V. A.; McIntosh H. V. (1966). "On the Degeneracy of the Kepler Problem". Pacific Journal of Mathematics. 19: 39–55. doi:10.2140/pjm.1966.19.39.

- ^ Lévy-Leblond, J. M. (1971). "Conservation Laws for Gauge-Invariant Lagrangians in Classical Mechanics". American Journal of Physics. 39 (5): 502–506. Bibcode:1971AmJPh..39..502L. doi:10.1119/1.1986202.

- ^ Gonzalez-Gascon, F. (1977). "Notes on the symmetries of systems of differential equations". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 18 (9): 1763–1767. Bibcode:1977JMP....18.1763G. doi:10.1063/1.523486.

- ^ Lie, S. (1891). Vorlesungen über Differentialgleichungen. Leipzig: Teubner.

- ^ Ince, E. L. (1926). Ordinary Differential Equations. New York: Dover (1956 reprint). pp. 93–113.

Further reading[]

- Baez, John (2008). "The Kepler Problem Revisited: The Laplace–Runge–Lenz Vector" (PDF). Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- Baez, John (2003). "Mysteries of the gravitational 2-body problem". Archived from the original on 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2004-12-11.

- Baez, John (2018). "Mysteries of the gravitational 2-body problem". Retrieved 2021-05-31. Updated version of previous source.

- D'Eliseo, M. M. (2007). "The first-order orbital equation". American Journal of Physics. 75 (4): 352–355. Bibcode:2007AmJPh..75..352D. doi:10.1119/1.2432126.

- Hall, Brian C. (2013), Quantum Theory for Mathematicians, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 267, Springer, ISBN 978-1461471158.

- Leach, P. G. L.; G. P. Flessas (2003). "Generalisations of the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector". J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 10 (3): 340–423. arXiv:math-ph/0403028. Bibcode:2003JNMP...10..340L. doi:10.2991/jnmp.2003.10.3.6. S2CID 73707398.

- Classical mechanics

- Orbits

- Rotational symmetry

- Vectors (mathematics and physics)

- Mathematical physics

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\partial }{\partial L}}\langle h(r)\rangle &=\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial L}}\left\{{\frac {1}{T}}\int _{0}^{T}h(r)\,dt\right\}\\[1em]&=\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial L}}\left\{{\frac {m}{L^{2}}}\int _{0}^{2\pi }r^{2}h(r)\,d\theta \right\},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7de9a0aa348d262a262b03f93c2028e1e6fddb08)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\boldsymbol {\eta }}&=\displaystyle {\frac {p^{2}-p_{0}^{2}}{p^{2}+p_{0}^{2}}}\mathbf {\hat {w}} +{\frac {2p_{0}}{p^{2}+p_{0}^{2}}}\mathbf {p} \\[1em]&=\displaystyle {\frac {mk-rp_{0}^{2}}{mk}}\mathbf {\hat {w}} +{\frac {rp_{0}}{mk}}\mathbf {p} ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/18ab15c42d041e367f125ff0e35053a58067c186)

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {A}}=\mathbf {A} +{\frac {mq}{2}}\left[\left(\mathbf {r} \times \mathbf {E} \right)\times \mathbf {r} \right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/20af66a19dc9936aa349110ad731be096a79f881)

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {A}}=\left({\frac {\partial \xi }{\partial u}}\right)\left(\mathbf {p} \times \mathbf {L} \right)+\left[\xi -u\left({\frac {\partial \xi }{\partial u}}\right)\right]L^{2}\mathbf {\hat {r}} ,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3b25780c204c1fbf553309e68374af2e32c721c9)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}\left(\mathbf {p} \times \mathbf {L} \right)={\frac {d\mathbf {p} }{dt}}\times \mathbf {L} =f(r)\mathbf {\hat {r}} \times \left(\mathbf {r} \times m{\frac {d\mathbf {r} }{dt}}\right)=f(r){\frac {m}{r}}\left[\mathbf {r} \left(\mathbf {r} \cdot {\frac {d\mathbf {r} }{dt}}\right)-r^{2}{\frac {d\mathbf {r} }{dt}}\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1794709ea896ac78d1edaef3d279f9dab3670758)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}\left(\mathbf {p} \times \mathbf {L} \right)=-mf(r)r^{2}\left[{\frac {1}{r}}{\frac {d\mathbf {r} }{dt}}-{\frac {\mathbf {r} }{r^{2}}}{\frac {dr}{dt}}\right]=-mf(r)r^{2}{\frac {d}{dt}}\left({\frac {\mathbf {r} }{r}}\right).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bfc59bbda2a5d28aff70e34cabe94e5626f2cd56)

![{\displaystyle \delta _{s}x_{i}={\frac {\varepsilon }{2}}\left[2p_{i}x_{s}-x_{i}p_{s}-\delta _{is}\left(\mathbf {r} \cdot \mathbf {p} \right)\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc05a043d35a8057d499c9388942a81fb94c7eee)

![{\displaystyle A_{s}=\left[p^{2}x_{s}-p_{s}\ \left(\mathbf {r} \cdot \mathbf {p} \right)\right]-mk\left({\frac {x_{s}}{r}}\right)=\left[\mathbf {p} \times \left(\mathbf {r} \times \mathbf {p} \right)\right]_{s}-mk\left({\frac {x_{s}}{r}}\right).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/85385129547171f032803166f12ce1d75c812f93)