Lassen Peak

| Lassen Peak | |

|---|---|

Lassen Peak volcano | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 10,457 ft (3,187 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 5,229 ft (1,594 m)[2] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 40°29′17″N 121°30′18″W / 40.488173056°N 121.505007786°WCoordinates: 40°29′17″N 121°30′18″W / 40.488173056°N 121.505007786°W[1] |

| Geography | |

Lassen Peak | |

| Location | Shasta County, California, U.S. |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Lassen Peak |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Less than 27,000 years |

| Mountain type | Lava dome |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 1914 to 1921 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike |

Lassen Peak, commonly referred to as Mount Lassen, is the southernmost active volcano in the Cascade Range of the Western United States. Located in the Shasta Cascade region of Northern California, it is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, which stretches from southwestern British Columbia to northern California. Lassen Peak reaches an elevation of 10,457 ft (3,187 m), standing above the northern Sacramento Valley. It supports many flora and fauna among its diverse habitats, which are subject to frequent snowfall and reach high elevations.

A lava dome, Lassen Peak has a volume of 0.6 cu mi (2.5 km3) making it the largest lava dome[3] on Earth. The volcano arose from the former northern flank of now-eroded Mount Tehama about 27,000 years ago, from a series of eruptions over the course of a few years. The mountain has been significantly eroded by glaciers over the last 25,000 years, and is now covered in talus deposits.

On May 22, 1915, a powerful explosive eruption at Lassen Peak devastated nearby areas, and spread volcanic ash as far as 280 mi (450 km) to the east. This explosion was the most powerful in a series of eruptions from 1914 through 1917. Lassen Peak and Mount St. Helens were the only two volcanoes in the contiguous United States to erupt during the 20th century.

Lassen Volcanic National Park, which encompasses an area of 106,372 acres (430.47 km2), was created to preserve the areas affected by the eruption, for future observation and study, to protect the nearby volcanic features, and to keep away anyone from settling too close to the volcano. The park, along with the nearby Lassen National Forest and Lassen Peak, have become popular destinations for recreational activities, including climbing, hiking, backpacking, snowshoeing, kayaking, and backcountry skiing. Lassen Peak is dormant, meaning the volcano is merely inactive, and it has a functioning magma chamber under the ground still capable of eruptions. Thus it poses a threat to the nearby area through lava flows, pyroclastic flows, lahars (volcanically induced mudslides, landslides, and debris flows), ash, avalanches, and floods. To monitor this threat, Lassen Peak and the surrounding vicinity are closely observed with sensors by the California Volcano Observatory.

Geography[]

Located in Lassen Volcanic National Park, Lassen Peak lies in Shasta County, 55 mi (89 km) east of the city of Redding, in the U.S. state of California.[4] Lassen Peak and the rest of the National Park area are surrounded by the Lassen National Forest,[5] which has an area of 1,200,000 acres (4,900 km2).[6] Nearby towns include Mineral in Tehama County and Viola in Shasta County.[4]

Lassen Peak reaches an elevation of 10,440 ft (3,180 m), according to 1992 data from the U.S. National Geodetic Survey;[1] 1981 data from the Geographic Names Information System lists the mountain's elevation at 10,457 ft (3,187 m).[7] Lassen Peak marks the southernmost major volcano in the Cascade Range, rising above the northern Sacramento Valley.[8] Bounded by the Sacramento Valley and the Klamath Mountains to the west and the Sierra Nevada mountain range to the south,[9] it is the second tallest peak in the California segment of the Cascades,[10] behind Mount Shasta, which lies 80 mi (130 km) to the north.[11] Due to its proximity to nearby volcanoes Mount Tehama and Mount Diller, it is not easy to distinguish from its neighboring peaks.[8]

Physical geography[]

Lassen Peak has the highest known winter snowfall amounts in California. There is an average annual snowfall of 660 in (1,676 cm), and in some years, more than 1,000 in (2,500 cm) of snow falls at its base elevation of 8,250 ft (2,515 m) at Lake Helen. The Lassen Peak area receives more precipitation (rain, sleet, hail, snow, etc.) than anywhere in the Cascade Range south of the Three Sisters volcanoes in Oregon.[12] Though the volcano lies too far to the south to support a permanent snow cover over the entire mountain,[8] the heavy annual snowfall on Lassen Peak creates fourteen permanent patches of snow on and around the mountain top, despite Lassen's rather modest elevation, but no glaciers.[13]

Lightning has been known to strike the area frequently during summer thunderstorms.[14] These can initiate fires. On July 23, 2012, a lightning strike started the Reading Fire 1 mi (1.6 km) to the northeast of the Paradise Meadow region, which was contained after it reached an area of 28,079 acres (113.63 km2).[15] During the summer and fall of 2016, the National Park Service carried out prescribed fires to help reduce the amount of fuel available for fires in the Mineral Headquarters area and the Manzanita and Juniper Lake areas, respectively.[16]

Ecology[]

Lassen Peak supports a variety of flora that include mountain hemlock, whitebark pine, and alpine wildflowers.[17] Mountain hemlocks generally only reach an elevation of 9,200 ft (2,800 m), while whitebark pines reach up to 10,000 ft (3,000 m).[18] Throughout the national park, forests can be found featuring red fir, mountain alder,[19] western white pine, white fir,[20] lodgepole pine,[21] Jeffrey pine,[22] ponderosa pine, incense cedar, juniper, and live oak.[23] Other plants found in the Lassen Peak area consist of coyote mint, lupines, mule's ears, ferns,[24] corn lilies, red mountain heathers,[25] pinemat manzanitas,[26] greenleaf manzanitas, bush chinquapins,[22] catchflies, Fremont's butterweed, buckwheat, granite gilia, mountain pride, mariposa tulips, creambush,[27] and a variety of chaparral shrubs.[23]

The various habitats in the Lassen Volcanic National Park support about 300 vertebrate species like mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and birds, including bald eagles, which are listed as "Threatened" under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and peregrine falcons, which were removed from the endangered species list in 1999.[28] In forested areas below 7,800 ft (2,400 m), animals include American black bears, mule deer, martens, brown creepers, mountain chickadees, white-headed woodpeckers, long-toed salamanders, and several bat species. At higher elevations, Clark's nutcrackers, deer mice, and chipmunks can be found among mountain hemlock stands, and subalpine zones with sparse vegetation host populations of gray-crowned rosy finches, pikas, and golden-mantled ground squirrels. Among scattered stands of pinemat manzanita, red fir, and lodgepole pine, animals include dark-eyed juncos, montane voles, and sagebrush lizards. Meadows at the bottoms of valleys along streams and lakes support Pacific tree frogs, Western terrestrial garter snakes, common snipes, and mountain pocket gophers.[28] Other animals found within the national park area include snakes like rubber boas, common garter snakes, and striped whipsnakes;[29] cougars;[30] amphibians like newts, salamanders, rough-skinned newts, and Cascades frogs;[31] 216 species of birds including MacGillivray's warblers, Wilson's warblers, song sparrows, spotted owls, northern goshawks, and bufflehead ducks;[32] five species of native fish that include rainbow trout, tui chubs, speckled daces, Lahontan redsides, and Tahoe suckers; and four invasive fish species including brook trout, brown trout, golden shiners, and fathead minnows.[33] Prominent invertebrate species include California tortoiseshell butterflies.[28]

Geology[]

Lassen Peak lies near the southern end of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, at the western edge of the Basin and Range Province. Like other Cascade volcanoes, it was fed by magma chambers produced by the subduction of the oceanic Juan de Fuca tectonic plate under the western edge of the continental North American tectonic plate. The region is also affected geologically by the Cascadia subduction zone, which dips eastward beneath the western coast of North America in the Pacific Northwest, as well as horizontal stretching to the east of crustal rock in the Basin and Range Province. About 3 million years ago, the southern limit of active volcanoes in the Cascades corresponded to the Yana Volcanic Center 19 mi (30 km) to the south of Lassen Peak, but currently the southern edge of the Lassen Volcanic National Park now marks the same border, indicating that the Cascade Arc's southern end migrates at a rate of 0.4 to 1 in (1.0 to 2.5 cm) annually.[9]

In the southern segment of the Cascades, volcanoes exhibit widespread and long-lived activity produced by magma that ranges from low-silica basalt to siliceous (silica-rich) rhyolite.[34] The Lassen volcanic center is fed by two magma chambers, one calc-alkaline reservoir common to the rest of the Cascade Volcanoes, and the other a smaller volume of low-potassium olivine tholeiitic basalt associated with the Basin and Range province.[9] Within the region, most if not all of the volcanic rock has erupted in the past 3 million years.[35] During this period, at least five large andesitic stratovolcanoes (such as Mount Maidu) formed in the vicinity of Lassen Volcanic National Park, building volcanic cones before going extinct and undergoing erosion.[36] For most volcanic centers in the Southern Cascades, one volcano becomes active and normally becomes extinct as another begins to erupt, but at the Lassen locus, the Maidu and Dittmar volcanic centers overlapped during the late Pliocene to the early Pleistocene.[34] Volcanism within the Lassen vicinity follows a trend of intermittent, episodic eruptions punctuating long periods of dormancy, a pattern which persisted through the late Pleistocene and Holocene.[37] During the past 825,000 years, the area has produced hundreds of explosive eruptions over an area of 200 sq mi (520 km2),[4] and the past 50,000 years have seen seven major silicic eruptive episodes that produced dacitic lava domes, tephra, and pyroclastic flows,[38] along with five periods of basaltic and andesitic lava flows.[39]

Local activity began 600,000 years ago with the formation of Brokeoff Volcano (alternatively known as Mount Tehama).[35] Around the same time, about 614,000 years ago, an explosive eruption southwest of Lassen Peak produced 20 cu mi (83 km3) of pumice and ash, covering the area between the vent and what is now the city of Ventura, California. This deposit, referred to as the Rockland tephra, reaches up to several inches in thickness within the San Francisco Bay area, and can be found as far as northern Nevada and southern Idaho.[40] The same eruption also formed one of three known calderas within the Cascade, the others being Crater Lake and the Kulshan Caldera at Mount Baker.[41] Shortly after, the Lassen volcanic center, a cluster of closely spaced volcanoes, formed in the area, covering the nearby caldera.[40] During the late Pleistocene it produced andesite lava flows that built the Brokeoff composite volcano (stratovolcano). Following the end of volcanism at Brokeoff Volcano hydrothermal fluids began chemically weathering minerals in the andesite flows, altering the once strong rocks into easily eroded materials. Glaciers and streams were able to rapidly erode deep channels into these altered volcanic rocks, reducing the once lofty peak of Brokeoff Volcano into the landscape we see today. Following the erosion of Brokeoff Volcano, volcanism migrated to the Lassen Domefield to the northeast.

Lassen Peak's lava dome formed about 27,000 years ago from a series of eruptions over a few years, undergoing significant glacial erosion between 25,000 and 18,000 years ago.[42] The bowl-shaped depression on the volcano's northeastern flank, called a cirque, was eroded by a glacier that extended out 7 mi (11 km) from the dome.[42] By 18,000 years ago, Lassen Peak started to form a mound-shaped dacite lava dome, pushing its way through Tehama's former northern flank. As the lava dome grew it shattered overlaying rock, which formed a blanket of angular talus around the emerging steep-sided volcano. Likely resembling the nearby 1,100-year-old Chaos Crags, Lassen Peak reached its present height in a relatively short time, probably in just a few years.[11] Within the past 1,000 years or so, activity at Lassen Peak has produced six dacite lava domes, erupted tephra and pyroclastic flows, and built Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds. It also created the rockfalls at Chaos Jumbles.[37]

The only Cascade volcano with an elevation above 10,000 ft (3,000 m) that is not a stratovolcano,[8] Lassen Peak is a rhyodacitic lava dome.[43] It represents one of the largest lava domes on Earth, with a height of 2,000 ft (610 m) above its surroundings,[42] and an approximate volume of 0.60 cu mi (2.5 km3).[44] Unlike more conventional, conical stratovolcanoes like Mount Shasta or Mount Rainier, Lassen Peak is part of a volcanic center that erupts from different vents, which each remain active for a number of years or decades but often do not erupt from the same vent twice, also known as a monogenetic volcanic field.[45] 2000 years after Lassen's formation, it was surrounded by glaciers which ate away at its spiny protrusions of dacite.[46] Due to glacial erosion from the last local glacial advance, which ceased roughly 15,000 years ago, Lassen's lava dome is now covered in broken rock fragments at the base of crags called talus deposits. Only its crag formations on its southern flank, near the summit trailhead, have not been significantly altered by glacial erosion.[47]

Subfeatures[]

The Lassen volcanic center includes Brokeoff Volcano, Lassen's dacitic lava dome, and a number of small andesitic shield volcanoes found northeast of Lassen Peak.[48] The Lassen dome field includes 30 dacitic lava domes such as Bumpass Mountain, Mount Helen, Ski Heil Peak, and Reading Peak;[48] other major lava domes include Chaos Crags, Eagle Peak, Sunflower Flat, and Vulcans Castle.[49] Nearby shield volcanoes include Prospect Peak and West Prospect Peak, and there are three cones close to Lassen Peak: Cinder Cone, Hat Mountain, and Raker Peak.[49] The hydrothermal area inside the Lassen Peak volcanic center, with features located southeast and southwest of Lassen Peak,[50] represents the largest geothermal area in the United States besides the one present at Yellowstone National Park.[46]

The Chaos Crags, a series of five small lava domes, represent the youngest part of Lassen volcanic center's dome field, reaching an elevation of about 1,800 ft (550 m) above their surroundings.[47] They were produced by vigorous explosive eruptions of pumice and ash followed by effusive activity,[47] which created unstable edifices that partially collapsed and formed pyroclastic flows made of incandescent lava blocks and lithic ash. Six domes were originally formed, though one was destroyed by a pyroclastic flow. Roughly 350 years ago, one of the domes collapsed to produce the Chaos Jumbles, an area where three enormous rockfalls transformed the local area and traveled as far as 4 mi (6.4 km) down the dome's slopes.[51]

Cinder Cone, which reaches an elevation of 700 ft (210 m) above its surrounding area in the northeastern region of the Lassen Volcanic National Park, forms a symmetrical pyroclastic cone.[51] The youngest mafic volcano in the Lassen volcanic center,[52] it is surrounded by unvegetated block lava and has concentric craters at its summit.[51] Cinder Cone is comprised by five basaltic andesite and andesite lava flows, and it also has two cinder cone volcanoes, with two scoria cones, the first of which was mostly destroyed by lava flows from its base.[52] In 1850 and 1851, a number of observers reported an eruption at Cinder Cone visible from more than 40 mi (64 km) away, with one observer near the mountain claiming to have observed a lava flow "running down the sides of the volcano."[51] However, despite these testimonies and accounts in newspaper articles and several scientific journals, the veracity of these eruptions has been questioned by scientists from the United States Geological Survey.[53] In addition to the fact that cinder cones usually erupt lava from base vents,[54] there is a lack of physical evidence suggesting activity at the volcano since its formation in 1650.[53] In addition, an old willow bush growing near the summit crater that was documented during the 1850s was still present in the 1880s after the alleged eruptions, suggesting that no eruptions took place during the 1850s.[37][55]

Human history[]

The areas surrounding Lassen Peak, especially to its east, south, and southeast, represented a meeting ground for Maidu, Yana, Yahi, and Atsugewi Native Americans.[56] The volcano is known among some native populations as Amblu Kai, which means "Mountain Ripped Apart" or "Fire Mountain," and as Kom Yamani, which means "Snow Mountain," among the Mountain Maidu.[57][58] Because the area was not suitable for permanent habitation, there is relatively scarce archaeological evidence of a native presence in the Lassen area.[56]

The first white man to reach Lassen Peak was Jedediah Smith, who passed through the area in 1821 as he made his way for the western coast of the United States.[56] After the California Gold Rush brought increased numbers of settlers into the area,[56] Lassen Peak was named in honor of a Danish blacksmith, Peter Lassen,[59] who guided immigrants past the peak to the Sacramento Valley during the 1830s.[11] This trail was replaced by the Nobles Emigrant Trail,[11] named for the guide William Nobles, who pioneered the trail in 1851.[60]

Lassen Peak's first recorded ascent took place in 1851, led by Grover K. Godfrey.[56] [61] In 1864, Helen Tanner Brodt became the first woman to reach the summit of Lassen Peak,[62] wanting to sketch the surrounding landscape. A tarn lake on Lassen Peak is named "Lake Helen" in her honor.[56] The Bumpass Hell, a hydrothermal vent area near Lassen Peak, was named after a pioneer who suffered burns there and lost his leg shortly after.[63] Other historic names for Lassen Peak include Mount Joseph (from 1827), Snow Butte, Sister Buttes, and Mount Lassen.[64]

Lassen Volcanic National Park[]

United States President Theodore Roosevelt established the Lassen Peak National Monument in 1907. Despite Native population claims that Lassen Peak was "full of fire and water" and would erupt again, this motion was based on the general belief that Lassen Peak was now extinct, and that its vicinity contained intriguing volcanic phenomena, which could be studied and observed.[11] Once the volcano became active again in 1914, the monument was expanded to establish the Lassen Volcanic National Park on August 9, 1916.[11] The park, 106,372 acres (430.47 km2) in area, can be reached from the California State Route 89 highway.[65]

Eruptive history[]

Ancient activity[]

Between 385,000 and 315,000 years ago, volcanism at the Lassen center shifted from andesitic stratovolcano construction to production of dacite domes.[66] Over the past 300,000 years, the Lassen Peak area has produced more than 30 lava domes, Lassen Peak being the largest. These lava domes formed as a result of rising lava that was pushed up but was too viscous to escape its source, creating steep edifices. Lassen Peak's lava dome formed 27,000 years ago from a series of eruptions over a few years, undergoing significant glacial erosion between 25,000 and 18,000 years ago.[42] No volcanic activity took place 190,000 years ago to roughly 90,000 years ago,[66] but during the last 100,000 years, there have been at least 12 periods of eruptive activity in the Lassen volcanic center,[48] and since 90,000 years ago, the Twin Lakes sequence has been producing mixed lavas with variable appearances and compositions, including andesite and basaltic andesite lava flows and agglutinated volcanic cones (made of fused pyroclastic rocks) located by the Lassen dome field. The Twin Lakes sequence includes the construction of the Chaos Crag dome complex between 1100 and 1000 years ago and eruptions at Lassen Peak beginning in 1914.[66]

Prior to 1914, Lassen Peak likely underwent at least one explosive eruption, which created a summit crater 360 ft (110 m) deep with a diameter of 1,000 ft (300 m). Deposits from older mudflows that can be traced specifically to the Lassen dome have also been found in Hat Creek, Lost Creek, and in a region to the east of the Devastated Area.[57]

1914–1921[]

On May 30, 1914, despite an apparent lack of precursor earthquakes,[67] Lassen became volcanically active again after 27,000 years of dormancy, when it produced a steam explosion that carved out a small crater with a fairly deep lake[68] on the volcano's summit.[42] The crater grew as it was carved by more than 180 similar phreatic explosions over the span of more than 11 months, reaching a length of 1,000 ft (300 m). On May 14, 1915, Lassen Peak erupted lava blocks, which extended as far as Manton, 20 mi (32 km) west of the mountain. By the next day, the volcano had produced a dacitic lava dome, between 63 and 68 percent silica, which occupied its summit crater.[69] On May 19, a large eruption destroyed this dome, and a new crater formed at the summit. No lava erupted, but parts of the dome fell on the upper flanks of the mountain, which were covered in more than 30 ft (9.1 m) of snow. The lava mixed with snow and rock to form a lahar (volcanically induced mudslide, landslide, and debris flow), 0.5 mi (0.80 km) in width, which coursed down the side of the volcano, traveling 4 mi (6.4 km) and reaching Hat Creek. After being deflected to the northwest at Emigrant Pass, the lahar extended an additional 7 mi (11 km) down Lost Creek. On May 20, the lower Hat Creek valley flooded with muddy water, which damaged ranch houses in the Old Station area and caused minor injuries among a few people, all of whom escaped.[69] Removing homes from their foundation,[70] the lahar also uprooted trees more than 100 ft (30 m) tall. The flood continued for another 30 mi (48 km), killing fish in the Pit River. Simultaneously, dacite lava with lower viscosity than dacite from the previous eruption filled the summit crater, overflowing and extending in two streams for 1,000 ft (300 m) down the mountain's western and northeastern sides.[69]

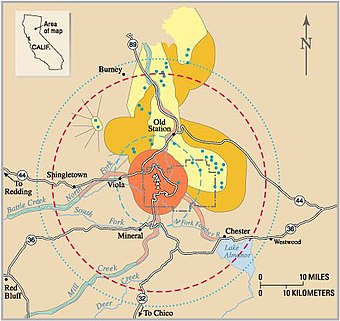

On May 22, 1915, at about 4:00 p.m., Lassen Peak produced a violent explosive eruption that ejected rock and pumice and formed a larger and deeper crater at its summit. Within 30 minutes, volcanic ash and gas formed a column that reached altitudes of more than 30,000 ft (9,100 m) and could be seen from the city of Eureka, 150 mi (240 km) to the west. This column underwent a partial collapse, generating a pyroclastic flow composed of hot ash, pumice, rock, and gas that destroyed 3 sq mi (7.8 km2) of land and spawned a lahar extending 15 mi (24 km) from the volcano and again reaching Hat Creek Valley.[71] Smaller mudflows also formed on every side of the volcano, as well a layer of pumice and volcanic ash that reached as far as 25 mi (40 km) northeast; volcanic ash was detected up to 280 mi (450 km) east at the city of Elko, Nevada.[72] Additionally, the lava flow on the volcano's northeastern flank was removed by this eruption, but not the similar deposit on the western flank.[69]

The eruptive output volume totaled 0.007 cu mi (0.029 km3), dwarfed by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, which had a volume of 0.24 cu mi (1.0 km3). The region on the volcano's northeastern flank destroyed by the eruptions, 3 sq mi (7.8 km2) in area, is now known as the Devastated Area, and it along with other deposits from the volcano has been altered by erosion and regrowth of vegetation,[72] though the vegetation in Devastated Area is sparse due to its siliceous (rich in silica), nutrient-deprived soil, which cannot sustain normal tree growth due to its lack of water retention.[73] Due to their small size and thin deposits, the 1915 eruptions will likely not be well-preserved geologically.[72]

After 1915, steam explosions continued for several years, indicating extremely hot rock beneath Lassen Peak's surface. In May 1917, an especially strong steam explosion formed the northern crater on Lassen Peak's summit,[72] with eruptions lasting two days and producing an ash cloud that extended 10,000 to 12,000 ft (3,000 to 3,700 m) into the sky. June saw 21 additional explosions reported, further transforming the crater and creating a new vent on Lassen Peak's northwestern summit. In June 1919, steam eruptions occurred, and similar activity was observed on April 8 and 9 in 1920, followed by steam eruptions lasting 10–12 hours in October of the same year. During February 1921, white steam erupted from eastern fissures on the volcano.[36] In total, about 400 eruptions were observed between 1914 and 1921,[68] which were the last eruptions in the Cascades before the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens,[74] which was the only other volcanic eruption in the contiguous United States during the 20th century.[75]

Documentation of 20th century eruptions through pictures and film[]

During its eruptions in the early 20th century, Lassen Peak attracted widespread media attention as the first volcano to erupt in the United States during the 20th century. Unlike eruptions at Mount Baker, Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, or Mount Hood during the 19th century, Lassen Peak's eruptions were very well documented by newspapers and extensively photographed.[76] Though there is a large supply of images documenting these eruptions at Lassen Peak, the best and most complete images were taken by the local businessman Benjamin Franklin Loomis. Using an 8x10-inch camera with glass-plate negatives, Loomis made his own film and set up a darkroom in a tent. He wrote of the eruption he witnessed on June 14, 1914, "The sight was fearfully grand."[42] Loomis's pictures were published in his book Pictorial History of the Lassen Volcano (1926); a number of his original plates remain in the archives of the National Park Service. His photographs have been used to help understand the timeline and geology of the 1915 eruptions of Lassen Peak.[42]

One of Lassen Peak's 1917 eruptions was captured on film by Justin Hammer from the nearby Catfish Lake. Originally silent, the film features sound effects added by his grandson, Craig Martin.[77] The film was rediscovered and published in 2015 by the .[78][79]

Recent activity and current threats[]

Lassen Peak remains an active volcano,[66] as volcanic activity including fumaroles (steam vents), hot springs, and mudpots can be found throughout Lassen Volcanic National Park. Their activity varies based on the season; during the spring, when meltwater is more abundant, fumaroles and pools of water have lower temperatures, while mudpots have more fluid mud supplies. During summer and droughts, they become drier and hotter, since they cannot be cooled by ground water. Geothermal activity can be observed at Bumpass Hell, Little Hot Springs Valley, Pilot Pinnacle, Sulphur Works, Devils Kitchen, Boiling Springs Lake, and Terminal Geyser, as well as the Morgan and Growler Hot Springs south of the national park in Mill Canyon. These are produced by the boiling of underground bodies of water, which generates steam. At Bumpass Hell, these features are at their most vigorous, with temperatures reaching 322 °F (161 °C) at Big Boiler, the park's biggest fumarole and one of the hottest hydrothermal fumaroles in the world. Because of their acidic conditions and heat, none of these hydrothermal bodies are safe for bathing except for at Drakesbad Guest Ranch.[35] Fumaroles near Lassen Peak in particular remained active through the 1950s, but have grown weaker over time;[72] they can still be found among the volcano's summit craters.[80] These hydrothermal features are monitored continuously for their physical and chemical conditions by the United States Geological Survey.[35]

Climbers reported steam eruptions in the summit craters for decades after activity apparently ceased in 1921, and the naturalist Paul Schulz documented 30 steam vents at the summit in the 1950s.[36] A report from the United States Geological Survey declared that "No one can say when, but it is almost certain that the Lassen area will experience volcanic eruptions again."[72] Similarly, the California Volcano Observatory lists its threat level as "Very High."[4][81] At the time of the early 20th century eruptions, the area surrounding the volcano was only sparsely populated, but a similar eruption today would threaten many lives and the northern Californian economy.[82] Volcanic eruptions occur with similar frequency to major earthquakes from the San Andreas Fault, and at least 10 eruptions have taken place within the state during the past 1,000 years, the most recent at Lassen Peak.[83] Under 1 percent of the state's population lives within hazard zones that could be affected by an eruption, but collectively hazard zones are visited by more than 20 million people each year.[81] Moreover, a number of the potentially active Californian volcanoes reside less than 100 mi (160 km) from highly populated areas,[83] and explosive eruptions could produce ash that travels for several hundred miles.[81] In the case of signs that suggest impending volcanic activity, the United States Geological Survey has a plan in place to utilize portable monitoring instruments, deploy scientists to the area,[45] and implement an emergency response plan developed by the National Park Service if an eruption were imminent.[84]

Although basaltic lava flows are the most common eruptive activity in the Lassen volcanic center, they could also produce more violent and thus more hazardous silicic lava flows,[85] in addition to building additional, unstable lava domes that could collapse and spawn pyroclastic flows that could extend for several miles.[86] Because Lassen Peak has a significant amount of snow and ice, these pyroclastic flows (or hot volcanic ash) might mix with water to form lahars (volcanically induced mudslides, landslides, and debris flows) that could destroy nearby communities.[87] Dacitic eruptions could produce volcanic columns of gas and ash that could threaten aircraft in the area.[88] Moreover, the Lassen volcanic center poses threats to visitors from sudden avalanches that could be entirely unrelated to eruptive activity. Due to the threat of an avalanche from nearby Chaos Crag if volcanic activity renewed in the area or an earthquake occurred, the Visitor Center for Lassen Peak located at Manzanita Lake closed in 1974.[11] In 1993, a rockfall with a volume of 13,000 cu yd (9,900 m3) fell down Lassen Peak's northeastern flank, but no visitors were harmed. Despite the volcano's current quiet state, rockfalls still pose significant hazards due to the peak's inherent instability.[51]

The volcano is monitored by the California Volcano Observatory, which has a sensor network that can measure increased seismicity, ground deformation, or gas emissions suggesting movement of magma towards the surface near the volcano.[72] The United States Geological Survey, in cooperation with the National Park Service, has been monitoring Lassen Peak and other volcanic areas in the park with tiltmeters, seismometers, and inclinometers.[68] Prior to 1996, geodetic surveys at Lassen Peak did not detect ground deformation, but Interferometric synthetic-aperture radar (InSAR) surveys between 1996 and 2000 suggested that downward subsidence was occurring at a rate of 0.39 in (10 mm) each year within a circular area with a diameter of 25 mi (40 km) centered just 3.1 mi (5 km) of the volcano.[89] As a result, additional surveys using the Global Positioning System took place in 2004,[89] and further InSAR surveys showed that subsidence continued through 2010.[90] Lassen Peak is one of four Cascade volcanoes that has undergone subsidence since 1990, with Medicine Lake Volcano, Mount Baker, and Mount St. Helens. Though not conclusively linked to a possible eruption, this subsidence may offer insight into how magma is stored within the region, tectonic setting, and how hydrothermal systems evolve over long periods of time.[90] GPS receivers have been in place to monitor deformation within the Lassen volcanic center since 2008,[91] and 13 seismometers in the vicinity, first installed in 1976 and since updated each decade, continually survey earthquakes within the locale.[92]

Recreation[]

The Lassen Volcanic National Park is visited by more than 350,000 people every year.[4] Incorporating more than 150 mi (240 km) of hiking trails, it is visited by people looking to hike or backpack during the summers. Popular winter activities include snowshoeing and backcountry skiing.[93] As the second-tallest volcano in Northern California, trailing only Mount Shasta,[10] Lassen Peak is frequently visited by climbers and hikers from around the world.[94] The summit opens for use most years near the end of June, remaining in use until heavy snow falls in October or November.[95] After a 9-year-old boy died from a collapsed retaining wall along the summit trail on July 29, 2009, the path closed for six years for construction, reopening in 2015.[94]

The mountain's summit trail can be accessed from a parking lot on the northern side of the California State Route 89.[39] The Lassen Peak Trail, which starts from this parking area, runs for 2.5 mi (4.0 km) with switchback turns,[39] a round-trip hike 5 mi (8.0 km) in length that ascends approximately 2,000 ft (610 m) from the trailhead at 8,500 ft (2,600 m) to the summit at 10,457 ft (3,187 m).[96] From the northeast summit, Lassen's 1915 mudflow and Prospect Peak are visible;[39] the northwestern summit offers views of Lassen's two bowl-shaped craters and Mount Shasta, 80 mi (130 km) to the north.[95]

The southern entrance to the park area has a winter sports area where visitors can ski,[97] snowshoe, and within the Lassen National Forest, visitors can also bicycle, go boating, or use snowmobiles.[6]

See also[]

- List of highest points in California by county

- List of Ultras of the United States

- List of volcanoes in the United States

References[]

- ^ a b c "Lassen". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ "Lassen Peak, California". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved October 30, 2021.[self-published source?]

- ^ Bullard, Fred (1984). Volcanoes of The earth (2 ed.). UT Press. pp. 565–566.

- ^ a b c d e "Lassen Volcanic Center: Summary". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. May 23, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. November 30, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "Lassen National Forest: About the Forest". United States Forest Service. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Peak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Harris 2005, p. 73.

- ^ a b c "Lassen Volcanic Center: Geology & History". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. December 13, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Suess 2017, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harris, Tuttle & Tuttle 2004, p. 542.

- ^ "Cascade Snowfall and Snowdepth". Skiing the Cascade Volcanoes. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ^ "Glaciers of California". Glaciers of the American West. Portland State University. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Hiking Safety". National Park Service. November 12, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Fire History". National Park Service. February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Current Fire Activity". National Park Service. October 14, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 29.

- ^ White 2016, p. 59.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 22.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 23.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 33.

- ^ a b Soares 1996, p. 63.

- ^ a b Soares 1996, p. 100.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Soares 1996, p. 62.

- ^ White 2016, p. 57.

- ^ a b c "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Animals". National Park Service. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Reptiles". National Park Service. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Mountain Lions". National Park Service. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Amphibians". National Park Service. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Birds". National Park Service. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park: Fish". National Park Service. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Formation of Volcanic Centers". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. December 13, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Clynne, M. A.; Janik, C. J.; Muffler, L. J. P. (December 4, 2009). Stauffer, P. H.; Hendley II, J. W. (eds.). ""Hot Water" in Lassen Volcanic National Park— Fumaroles, Steaming Ground, and Boiling Mudpots: U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 101-02". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c Harris 2005, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Harris 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Harris 2005, pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b c d Harris 2005, p. 97.

- ^ a b Harris 2005, p. 90.

- ^ Harris 2005, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clynne et al. 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Hildreth 2007, p. 40.

- ^ Hildreth 2007, p. 44.

- ^ a b Clynne, M. (May 24, 2005). Diggles, M. (ed.). "Volcano Hazards of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Area, California: Fact Sheet 022-00". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Harris 2005, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Harris 2005, p. 93.

- ^ a b c "Lassen Volcanic Center: Geological Summary". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "Lassen Volcanic Center: Synonyms and Subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Janik & McLaren 2010, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 2005, p. 94.

- ^ a b "The Formation of Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. December 13, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Harris 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Harris 2005, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Clynne, M. (May 24, 2005). Diggles, M. (ed.). "How Old is "Cinder Cone"?–Solving a Mystery in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California: Fact Sheet 023-00". Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Lopes 2005, p. 115.

- ^ a b Lopes 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Nevins 2017, p. 72.

- ^ Brown, Thomas P. (May 30, 1940). "Over the Sierra". Indian Valley Record. p. 3. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Noble Emigrant Trail, Susanville: Historical Landmark". Office of Historic Preservation. California Department of Parks and Recreation. 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Godfrey, Grove (December 1859). "Lassen's Peak". Hutching's California Magazine. IV: 299–302. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Harris, Tuttle & Tuttle 2004, p. 549.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 91.

- ^ White 2016, p. 58.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park". National Geographic. National Geographic Partners and National Geographic Society. November 5, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Eruption History of the Lassen Volcanic Center and Surrounding Region". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. October 1, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Harris, Tuttle & Tuttle 2004, p. 551.

- ^ a b c d Clynne et al. 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Clynne et al. 2014, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clynne et al. 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Harris, Tuttle & Tuttle 2004, p. 547.

- ^ "The 1914–1917 Eruption of Lassen Peak". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. September 10, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Osterkamp & Hedman 1982, p. 7.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 74.

- ^ Irwin, James; Mercer, Brandon (May 29, 2014). "Lassen Peak Began Years Of Eruptions 100 Years Ago, Building To Massive Blasts And A National Park". CBS SF Bay Area. CBS. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ Mt Lassen 1915, Shasta Historical Society, April 29, 2015, retrieved February 19, 2016

- ^ Klemetti, Erik. "Watch One of the First Volcanic Eruptions Ever Filmed". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ Foxworthy & Hill 1982, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Stovall, Marcaida & Mangan 2014, p. 2.

- ^ "Eruptions of Lassen Peak, California, 1914 to 1917 — A Centennial Commemoration". United States Geological Survey. May 21, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Stovall, Marcaida & Mangan 2014, p. 1.

- ^ "The Eruption of Lassen Peak". National Park Service. February 28, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Lava Flows at Lassen Volcanic Center". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. November 14, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Pyroclastic Flows at Lassen Volcanic Center". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. November 14, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Lahars at Lassen Volcanic Center". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. November 14, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Ash and Tephra from Lassen Volcanic Center". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. June 11, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Parker, Biggs & Lu 2016, p. 117.

- ^ a b Parker, Biggs & Lu 2016, p. 126.

- ^ "Deformation Monitoring at Lassen Volcanic Center". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. January 3, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Seismic Monitoring at Lassen Volcanic Center". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. June 18, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. October 3, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Stienstra, Tom (August 1, 2015). "Trail to Top of Volcanic Lassen Peak Finally Reopens". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Harris 2005, p. 98.

- ^ "Hiking Lassen Peak Trail". National Park Service. June 13, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ Lopes 2005, p. 116.

Sources[]

- Clynne, M. A.; Christiansen, R. L.; Stauffer, P. H.; Hendley II, J. W.; Bleick, H. (2014). A Sight "Fearfully Grand"—Eruptions of Lassen Peak, California, 1914 to 1917: Fact Sheet 2014–3119. National Park Service, Lassen Association, and the United States Forest Service.

- Foxworthy, B. L.; Hill, M. (1982). Volcanic Eruptions of 1980 at Mount St. Helens: The First 100 Days (U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper, 1249). United States Geological Survey. OCLC 631692808.

- Harris, S. L. (2005). "Chapter 6: Lassen Peak". Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes (Third ed.). Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. pp. 73–98. ISBN 0-87842-511-X.

- Harris, A. G.; Tuttle, E.; Tuttle, S. D. (2004). Geology of National Parks. Kendall Hunt.

- Hildreth, W. (2007). Quaternary Magmatism in the Cascades, Geologic Perspectives. United States Geological Survey. Professional Paper 1744. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Janik, C. J.; McLaren, M. K. (2010). "Seismicity and Fluid Geochemistry at Lassen Volcanic National Park, California: Evidence for Two Circulation Cells in the Hydrothermal System". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 189 (3–4): 257–277. Bibcode:2010JVGR..189..257J. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.11.014.

- Nevins, M. Eleanor (2017). "'You shall not become this kind of people': Indigenous political argument in Maidu linguistic text collections". In Kroskrity, Paul V.; Meek, Barbra A. (eds.). Engaging Native American Publics: Linguistic Anthropology in a Collaborative Key. New York: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-138-95094-8.

- Lopes, R. M. C. (2005). The Volcano Adventure Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521554534.

- Osterkamp, W.R.; Hedman, E.R. (1982). Perennial-Streamflow Characteristics Related to Channel Geometry and Sediment in Missouri River Basin. United States Geological Survey.

- Parker, A. L.; Biggs, J.; Lu, Z. (2016). "Time-scale and Mechanism of Subsidence at Lassen Volcanic Center, CA, from InSAR". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. Elsevier. 320: 117–127. Bibcode:2016JVGR..320..117P. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.04.013. hdl:1983/aa5d121d-1170-4ff9-b59d-c7701de31714.

- Soares, J. R. (1996). 75 Hikes in California's Lassen Park & Mount Shasta Regions. The Mountaineers Books.

- Stovall, W. K.; Marcaida, M.; Mangan, M. T. (2014). The California Volcano Observatory—Monitoring the State's Restless Volcanoes: Fact Sheet 2014–3120. United States Geological Survey.

- Suess, B. (2017). Hiking Northern California: A Guide to the Region's Greatest Hiking Adventures. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1493002719.

- White, M. (2016). Lassen Volcanic National Park: Your Complete Hiking Guide. Wilderness Press. ISBN 978-0899977997.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lassen Peak. |

- "Lassen Volcanic National Park Web Site". National Park Service. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- "Lassen Volcanic Center". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- "Volcano Hazards Assessment for the Lassen Region, Northern California". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- Cascade Range

- Volcanoes of Shasta County, California

- Highest points of United States national parks

- Lassen Volcanic National Park

- Subduction volcanoes

- Lava domes

- Cascade Volcanoes

- Cirques

- 20th-century volcanic events

- Volcanoes of California

- North American 3000 m summits