Leslie Van Houten

Leslie Van Houten | |

|---|---|

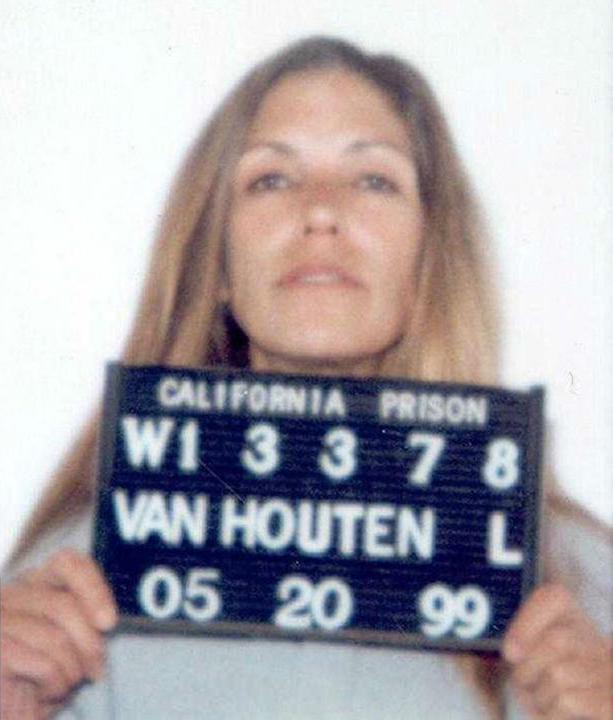

Mug shot taken in May 1999 | |

| Born | Leslie Louise Van Houten August 23, 1949 Altadena, California, U.S.[1] |

| Other names | Louella Alexandria, Leslie Marie Sankston, Linda Sue Owens and Lulu |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Conviction(s) | California Penal Code Section 187, murder in the first degree California Penal Code Section 182–187, conspiracy to commit first degree murder[2][3] |

| Criminal penalty | Death, commuted to life imprisonment with parole[2][3] |

Leslie Louise Van Houten (born August 23, 1949) is an American convicted murderer and former member of the Manson Family. During her time with Manson's group, she was known by various aliases such as Louella Alexandria, Leslie Marie Sankston, Linda Sue Owens and Lulu. Van Houten was arrested and charged in relation to the 1969 killings of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. She was convicted and sentenced to death. However, the California Supreme Court decision on People v. Anderson then ruled in 1972 that the death penalty was unconstitutional, resulting in her sentence being commuted to life in prison. Her conviction was then overturned in a 1976 appellate court decision which granted her a retrial. Her second trial ended with a deadlocked jury and a mistrial. At her third trial in 1978, she was convicted of two counts of murder and one count of conspiracy and sentenced to seven years to life in prison.[3] In relation to her case, high courts, parole boards and the state governor have said that an inexplicable or racial motive for murder could merit exemplary punishment and outweigh any evidence of subsequent reform.[citation needed]

Early life[]

Van Houten was born on August 23, 1949 in the Los Angeles suburb of Altadena to Paul Van Houten and Jane (née Edwards). She is of Irish, English, Scottish, Dutch, and German descent. She grew up in a middle-class churchgoing family along with an older brother and two adopted siblings, a brother and a sister, who were Korean. Her mother and father divorced when she was 14. She began taking LSD, Benzedrine and smoking hashish around age 15, running away for a time, but returning to complete high school. At 17, she became pregnant and was forced by her mother to undergo an abortion. Van Houten's mother informed her sometime later that the procedure could not be referred to as an abortion as the fetus was too mature. She instructed the girl to bury the late term aborted baby in their backyard.[4] Van Houten stated that after this event, she felt very removed from her mother and harbored intense anger toward her. She had a period of interest in yoga and took a year-long secretarial course, but became a hippie, living at a commune.[5][6][7][8]

Manson Family[]

After a few months in a commune in Northern California, Van Houten met Catherine Share and Bobby Beausoleil and moved in with them and another woman during the summer of 1968. The four broke up after jealous arguments, and Share left to join Charles Manson's commune. Van Houten, then aged 19, followed Share. At this time, she phoned her mother to say she was dropping out and would not be making contact again.[5] Manson decided when they would eat, sleep, and have sex, and with whom they would have sex. He also controlled the taking of LSD, giving followers larger doses than he himself took. According to Manson, "When you take LSD enough times, you reach a state of nothing, of no thought".[9] According to Van Houten, she became "saturated in acid" and could not grasp the existence of those living a non-psychedelic reality.[10][11][12]

From August 1968, Manson and his followers were based at the Spahn Ranch. Manson ostensibly ran his Family based on hippie-style principles of acceptance and free love. At the remote ranch, where they were isolated from any other influences, Manson's was the only opinion heard. At every meal he would lecture repetitively. Van Houten said Manson's attitude was that she "belonged to Bobby".[13][14][15][16] According to Van Houten she and other Manson followers looked to 14-year-old Family member Dianne Lake as the "empty vessel", the epitome of what women were supposed to be in the Manson system of values.[7] When Barbara Hoyt spoke at Van Houten's parole hearing in 2013, she said that Van Houten was considered a "leader" in the Manson Family.[6][17]

Murders[]

Motive[]

Manson, who denied responsibility, never explained a motive for the murders. Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi suggested Manson was attempting to start a racial civil war.[18] The racial nature of the motive for the murders Van Houten was convicted of was later adduced by a judge, increasing the gravity of her offense.[6][15][16]

Murders of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca[]

On August 9, 1969, Van Houten, Tex Watson, Patricia Krenwinkel, Linda Kasabian, Susan Atkins, Clem Grogan and Manson went to the house of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca.[10][19][20][21][22] Manson entered the house with Watson, then left with Atkins, Grogan and Kasabian. Krenwinkel, Van Houten, and Watson murdered the couple.[6][16][23] He allegedly sent the others to kill an actor, but Kasabian claims she led Atkins and Grogan to an incorrect address.[24]

Trial[]

Tex Watson, who had shot or stabbed all of the victims at the Tate and LaBianca murders and who inflicted most of the fatal or non-survivable injuries, was not arraigned with the others at the main 'Manson' trial, which covered both the Tate and LaBianca murders. Manson was accused of orchestrating both attacks, but the only defendants at the trial whose murder charges were for actually inflicting injuries on the LaBiancas were Van Houten and Krenwinkel.[8] Unlike the others, Van Houten was not accused of the murders of Tate and her friends.[25]

Manson opposed his three female co-defendants running a defense that he had asked them to commit killings. Van Houten did not appear to take the court seriously (she later claimed to have been supplied with LSD during the trial) and giggled during testimony about the victims. She took the stand and admitted committing the murders with which she was charged and denied that Manson had been involved.[26] An often-cited example of how he seemed to exert control over Van Houten and the others was when Manson carved an X on his forehead and she and the other two women defendants copied him. In the latter stages of the trial they stopped mimicking him, Bugliosi suggested, because they realized it was making the extent of his influence over them apparent.[27]

Van Houten dismissed three defense lawyers in succession for claiming her actions were attributable to Manson's control over her.[28][page needed] When her lawyer was asking an expert witness about the effect of LSD on judgment, Van Houten shouted that, "This is all such a big lie, I was influenced by the war in Vietnam and TV".[29]

On March 29, 1971, she was convicted of murder along with the other defendants. During the sentencing phase of the trial, in an apparent attempt to exonerate Manson, Van Houten testified that she had committed a killing in which she was not, in fact, involved. She told a psychiatrist of beating her adopted sister, leading him to characterize her as "a spoiled little princess" and a "psychologically loaded gun", and was adamant that Manson had no influence over her thought processes or behavior. Van Houten also told the psychiatrist that she would have gone to jail for manslaughter or assault with a deadly weapon without ever meeting Manson. When her lawyer, attempting to show she felt remorse, asked if she felt sorrow or shame for the death of Rosemary LaBianca, Van Houten replied "sorry is only a five-letter word" and "you can't undo something that is done". In cross-examination, Van Houten aggressively implicated herself in inflicting wounds while the victim was living, and severely wounding the victim, severing her spine, which might have been fatal by itself. She vehemently denied acting on instructions from Manson, and said a court-appointed attorney who "had a lot of different ideas on how to get me off" had told her to claim Manson ordered the killings.[30]

Van Houten was sentenced to be executed; she was the youngest woman ever condemned to death in California. No death row for female prisoners existed, and a special unit was built. The death sentences were automatically commuted to life in prison after the California Supreme Court's People v. Anderson decision resulted in the invalidation of all death sentences imposed in California prior to 1972.[6][8] With murder (or manslaughter) convictions she was eligible for parole once she had served seven years.[31] In order to be released after seven years, her first parole hearing would have had to have granted her parole and the governor not veto the decision. In his bestselling book Helter Skelter, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi said that "his guess" was that all three women would be released after 15–20 years.[32]

Re-trial[]

Van Houten was granted a retrial in 1977 due to the failure to declare a mistrial when her lawyer died. Her defense argued that Van Houten's capacity for rational thought had been diminished due to LSD use and Manson's influence. The jury could not agree on a verdict. According to what the jury foreman later told reporters, they thought it was difficult on the basis of the evidence to determine whether Van Houten's judgment had been unimpaired enough for a verdict of first degree murder rather than manslaughter.[33]

It was reported in the news media that because of time already served, Van Houten could go free that year if she was convicted of manslaughter.[33][34] By law, prosecutors are not allowed to mention the possibility of the defendant being released on parole when arguing for a murder rather than manslaughter conviction because it is considered highly prejudicial to the defendant.[35]

Second re-trial[]

The prosecution in 1970–71 had emphasized that the motive had nothing to do with robbery and the killers ignored valuable pieces of property. At Van Houten's second re-trial, the prosecution, who were now being aided by a specialist in diminished responsibility, altered the charges by using the theft of food, clothing and a small sum of money taken from the house to add a charge of robbery, whereby the felony murder rule tended to undermine a defense of reduced capacity. She was on bond for six months before being found guilty of first degree murder. Van Houten was given a life sentence that entailed eligibility for parole, for which the prosecutor said she would one day be suitable.[6][8]

Post-trial events[]

After the first trial, Van Houten and her female co-conspirators Susan Atkins and Patricia Krenwinkel were housed in a special housing unit built at the California Institution for Women. They were initially kept separate from the prison population, because they were viewed as a threat to the other inmates.

In the early 1970s, Van Houten, Atkins and Krenwinkel worked with a social worker, Karlene Faith, who sought to help them re-establish their identities separate from the Manson Family.[36] Faith later wrote a book about her work with the women, The Long Prison Journey of Leslie Van Houten. In the book, Faith tells how two of the women believed that they would "grow wings and become fairies" after the expected race war had occurred. The women told Faith that they obtained this belief from Manson. Faith viewed all three of the Manson women as victims, and lobbied for their early release from prison.[37] Faith's work with the Manson women was later portrayed in the feature film, Charlie Says.

Van Houten was also befriended by film director John Waters. Moreover, he campaigned for her early release from prison.[38]

In 1975, the Manson women were moved to the general population at the California Institute of Women.

Parole requests[]

Under California law, some life sentences are eligible for parole, and a parole board rejection of an application does not preclude a different decision in the future.[39] Susan Atkins and Patricia Krenwinkel (who were originally convicted along with Van Houten and Manson at the main trial) had both been found guilty of the most notorious crime, the murder of five people at 10050 Cielo Drive. In addition, Krenwinkel was also convicted of the murders of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, while Atkins was also convicted of murdering Gary Hinman.

Only one member of the Manson Family has been convicted of murder and later released: Steve "Clem" Grogan.[6] Grogan, convicted and given a death sentence by the jury for the torture-murder of Donald Shea with Manson, was freed in 1985.[40] Bruce M. Davis, also an accomplice of Manson in the killing of Shea, and with a second conviction for the Gary Hinman killing, was given a parole board recommendation for release in 2010 although very few inmates with even a single conviction on a charge of murder had been able to obtain parole in California before 2011.[6][41][42][43] In each case, the sitting governor ordered a review or reversed the decision.[44] "Tex" Watson was denied parole for the 15th time on October 27, 2016.[45]

After receiving her 13th rejection, in which the hearing concluded she posed "an unreasonable risk of danger to society", Van Houten took legal action. Judge Bob Krug ordered the board to re-hear the application because their reasoning turned solely on the unalterable gravity of her offense and effectively gave her life without parole, "a sentence unauthorized by law". The judgment was overturned by a higher court, which said although parole hearings must consider evidence for an inmate being rehabilitated, a hearing had discretion to deny parole based solely on a review of the circumstances of the crime, if "some evidence" supported their decision.[15][31]

In 2013, Van Houten was denied parole for the 20th time at a hearing. In announcing a decision to deny parole, the commissioner of the hearing board said that she had failed to explain how someone of her good background and intelligence could have committed such "cruel and atrocious" murders.[7]

On April 14, 2016, a two-person panel of the California Parole Board recommended granting Van Houten's parole request, but California Governor Jerry Brown vetoed the release on the grounds that: "Both her role in these extraordinarily brutal crimes and her inability to explain her willing participation in such horrific violence cannot be overlooked and lead me to believe she remains an unacceptable risk to society if released."[46]

On September 29, 2016, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge William C. Ryan issued an 18-page ruling upholding the governor's reversal earlier in the year of a parole board's decision to release Van Houten. Ryan wrote that there was "some evidence" that Van Houten presents an unreasonable threat to society.[47] On December 21, the California Supreme Court denied Van Houten's petition to hear the case.[48]

Van Houten has long since renounced Manson, who died in prison in November 2017. She has expressed remorse for her crimes, and at her 2013 parole hearing, her attorney argued that her value system was completely different from what it was in 1972. She let it be known that she "takes offense to the fact that Manson doesn't own up" to his role in the murders. She told Vincent Bugliosi, the man who sent her to prison, "I take responsibility for my part, and part of my responsibility was helping to create him." She has written several short stories, once edited the prison newspaper and did some secretarial work at the prison.[49]

Van Houten was again recommended for parole at her 21st parole hearing on September 6, 2017. The two-member panel found that Van Houten had radically changed her life in the more than 40 years she had been incarcerated.[50] Governor Jerry Brown again denied her parole on January 19, 2018. Her legal team stated they would fight the decision.[51] On June 29, 2018, Van Houten's parole was once again vetoed. The judge was again William C. Ryan, who said: "Unless the inmate can demonstrate that there is no evidence to support the governor's conclusion that the inmate is a current danger to public safety, the petition fails to state a prima facie case for relief and may be summarily denied."[52]

On January 30, 2019, during her 22nd parole hearing, Van Houten was recommended for parole for the third time. But on June 4, 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom overruled the parole board's recommendation, claiming the then 69-year-old Van Houten was still a "danger to society" and that she had "potential for future violence".[53] She appealed the governor's decision, but on September 21, 2019, the appeals court panel ruled 2–1 against reversing it.[54]

Van Houten was recommended for parole for the fourth time at a 23rd parole hearing on July 23, 2020, and a 120-day legal review period began. On November 28, Governor Newsom again rejected the board's recommendation and vetoed Van Houten's parole. Among his reasons for denial, Newsom stated the then 71-year-old Van Houten "currently poses an unreasonable danger to society if released from prison".[55][56] Again, her lawyer, Rich Pfeiffer, said they would appeal the governor's latest decision.[57]

In the media[]

Van Houten's parole hearings have appeared on Court TV and attracted nationwide media attention. They have featured comments from former prosecutors, relatives of her victims, and relatives of the victims of other killers.[58][59][60] Filmmaker John Waters has actively advocated for Van Houten's parole, although he acknowledges that the horror in which Manson's female accomplices are still held means public support for her release may be futile.[11][8][61][62]

Dramatic portrayals[]

Leslie Van Houten was first portrayed by actress in the 1976 made-for-TV film Helter Skelter. San Francisco-based actress Connie Champagne portrayed Van Houten in 's long-running 1989 stage play The Charlie Manson Story, first at and then , a black comedy directed by . The production was the first to de-glamorourize the Manson-myth and to question Manson's belief in the so-called "Helter Skelter." The 2009 film Leslie, My Name Is Evil (released in some countries under the titles Manson Girl and Manson, My Name Is Evil) is partially based on Van Houten's early life and stars actress Kristen Hager as Van Houten. In Helter Skelter (2004 remake of the 1976 film) Van Houten was portrayed by actress . A year earlier, in 2003, Amy Yates portrayed Leslie Van Houten in the film The Manson Family. In the 2015 NBC fictional series Aquarius, which centers on the Los Angeles Police Department and the Manson murders, Emma Dumont portrays a character named "Emma", who is loosely based on Van Houten. Tania Raymonde portrayed Van Houten in Susanna Lo's 2016 film . Later in 2016, Greer Grammer portrayed Van Houten in Leslie Libman's film , which starred MacKenzie Mauzy as Kasabian. In 2018 she was portrayed by in the made-for-TV documentary . Also in 2018, English actress Hannah Murray played Van Houten in the feature movie Charlie Says. And in 2019, Van Houten was played by Victoria Pedretti (credited as "Lulu") in Quentin Tarantino's film Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.[63]

See also[]

- Ronald W. Hughes, her first attorney

References[]

- ^ Sanders, Ed; The Family, p. 74

- ^ Jump up to: a b Transcript of Subsequent Parole Consideration Hearing. State of California. Hearing 6 September 2017. Transcribed 16 September 2017. Accessed 10 October 2017. Acquired through California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Request for Parole Suitability Hearing Transcript

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Manson follower Leslie Van Houten granted parole in notorious murders". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ "Leslie Van Houten, Ex-Manson Follower, Approved for Parole". NBC News. New York: NBCUniversal. AP. September 7, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. New York City: Arrow Books. pp. 565–566. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Walker, Tim (June 6, 2013). "Leslie Van Houten, youngest member of Charles Manson's 'Family', has parole denied for 20th time". The Independent. London.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c CieloDrive.com, retrieved December 17, 2014, "State of California Board of Parole Hearings: In the matter of the Life Term Parole Consideration Hearing of: Leslie Van Houten"

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Linder, Douglas O. (2014). "The Charles Manson (Tate–LaBianca Murder) Trial: The Defendants". Famous Trials. University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law.

- ^ Winn, Denise. The Manipulated Mind: Brainwashing, Conditioning, and Indoctrination. p. 168.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lorentzen, Christian (November 7, 2013). "The Way Out of a Room Is Not Through the Door". London Review of Books. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leslie Van Houten: A Friendship, Part 5 of 5 retrieved 16/12/14

- ^ Meares, Hadley Hall (October 22, 2014). "The Story of the Abandoned Movie Ranch Where the Manson Family Launched Helter Skelter". Curbed. Los Angeles. Retrieved December 18, 2014 – via CultEducation.com.

- ^ Guinn, Jeff. Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. p. 126.

- ^ The Press on Trial: Crimes and Trials as Media Events edited by Lloyd Chiasso p 161

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "High Court Spurns Leslie Van Houten's Bid for Release". Metropolitan News-Enterprise. June 24, 2004. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Encore Presentation: Interview with Leslie Van Houten". CNN. Larry King Weekend. June 29, 2002. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ^ Fox News, June 6, 2013, Parole denial for Leslie Van Houten suggests stigma too great for release. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1994) [1974]. Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders (25th anniversary ed.). W.W. Norton. pp. 311–312. ISBN 0-393-08700-X.

- ^ "Rock and Roll's Most Infamous Tour Manager". VICE.

- ^ "cc | Grand Theft Parsons : Phil Kaufman [ Interview ] »". www.counterculture.co.uk.

- ^ "Road Mangler Deluxe" – via Amazon.

- ^ "True story of Sharon Tate's death". Goodhousekeeping. July 30, 2019.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (2014). "The Influence of the Beatles on Charles Manson". Famous Trials. University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (2014). "Testimony of Linda Kasabian in the Charles Manson Trial". Famous Trials. University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (2014). "Closing Argument, The State of California v. Charles Manson et al. Delivered by Vincent Bugliosi". Famous Trials. University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. Arrow Books. p. 609. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. Arrow Books. p. 594. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Linder, Douglas (2008). The Trial of Charles Manson.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. Arrow Books. p. 595. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. Arrow Books. pp. 184–199. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Deutsch, Linda (May 24, 2002). "Hearing held for Manson follower". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. Arrow Books. p. 664. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lodi News-Sentinel-California, Aug 8, 1977, (UPI) Houten May Be Set Free.

- ^ "Judge orders new parole hearing for Charles Manson follower Leslie Van Houten". Lodi News–Sentinel. Associated Press. June 5, 2002. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2008 – via Highbeam Research.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter. Arrow Books. p. 607. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- ^ Jeffrey Melnick, "Keeping Faith With the Manson Women," The New Yorker, August 1, 2018.

- ^ Karlene Faith, The Long Prison Journey of Leslie Van Houten: Life Beyond the Cult (Northeastern University Press, 2001) [1]

- ^ Walters, Ben (November 8, 2018). "John Waters: Why the auteur of outrage won't joke about the Manson murders". The Guardian.

- ^ Cult Education Institute retrieved 18/12/214 Van Houten parole hearings

- ^ For it being a torture murder, see: DiBiase, Thomas A. (2014). No-Body Homicide Cases: A Practical Guide to Investigating, Prosecuting, and Winning Cases When the Victim Is Missing. p. 189.

- ^ "Manson follower Leslie Van Houten denied parole". New York Daily News.

- ^ "Bruce Davis Parole Denied: Schwarzenegger Rejects Parole for Manson Follower". Huffington Post. August 28, 2010.

- ^ "In California, Victims' Families Fight for the Dead". The New York Times. August 19, 2011.

- ^ Fortin, Jacey (June 24, 2017). "Bruce Davis, a Charles Manson Follower, Has Parole Blocked for Fifth Time". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Hamilton, Matt (October 28, 2016). "Parole denied for convicted Manson follower Charles 'Tex' Watson". MSN.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ "California Governor Denies Parole for Ex-Manson Follower". NBC News. Associated Press. July 23, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Judge deals blow to former Manson family member's latest bid to win freedom". Los Angeles Times. October 6, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ O'Brien, Brendan (December 22, 2016). "California Supreme Court denies Manson follower's petition". Reuters. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1994) [1974]. Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders (25th anniversary ed.). W. W. Norton. p. 659. ISBN 9780393087000.

- ^ Hamilton, Matt. "Manson follower Leslie Van Houten granted parole in notorious murders; Brown will make final decision". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ "Manson follower Leslie Van Houten denied parole by governor". CNBC. January 20, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "Judge denies parole to former Charles Manson follower Leslie Van Houten". Los Angeles Times. June 29, 2018.

- ^ "California governor again rejects parole for Manson follower Van Houten". UPI. June 4, 2019.

- ^ "Manson follower Van Houten loses appeal for parole". UPI. September 21, 2019.

- ^ Mossburg, Cheri; Kim, Allen (July 24, 2020). "Manson follower recommended for parole for the fourth time, but California governor has final say". CNN. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Governor nixes parole for Manson follower Leslie Van Houten". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Vigdor, Neil (November 29, 2020). "California Governor Blocks Release of Manson Follower Leslie Van Houten Gov. Gavin Newsom reversed a decision by the state parole board granting her release after about 50 years in prison". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "Former Manson disciple denied parole". The Age. September 8, 2006. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ^ "Former Manson disciple Leslie Van Houten denied parole". The San Diego Union–Tribune. Associated Press. September 6, 2006. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ "Manson follower denied parole for the 18th time". Charleston Daily Mail. Associated Press. August 31, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2008 – via Highbeam Research.[dead link]

- ^ "John Waters: Manson Family Member Should Be Free". NPR.org. National Public Radio. August 5, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ Waters, John (August 3, 2009). "Leslie Van Houten: A Friendship". Huffington Post. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Kopalo, Jon (25 July 2019). "How the Cast of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Compares to the Real-life Players". E! Online. NBCUniversal. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- 1949 births

- 20th-century American criminals

- American female murderers

- American murderers

- American people convicted of murder

- American people of Dutch descent

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Living people

- Manson Family

- People convicted of murder by California

- People from Altadena, California

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by California