Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Steffens | |

|---|---|

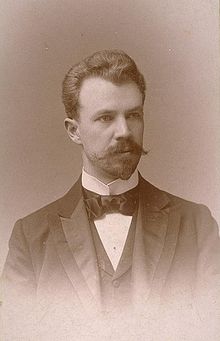

Steffens in 1895. Photo by Rockwood. | |

| Born | Joseph Lincoln Steffens April 6, 1866 San Francisco, California, US |

| Died | August 9, 1936 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of California |

| Occupation | Muckraking journalist |

| Employer |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Josephine Bontecou (m. 1881–1911), Ella Winter (m. 1924–1936) |

| Children | Pete Steffens |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Steffens and Elizabeth Louisa Symes |

Lincoln Austin Steffens (April 6, 1866 – August 9, 1936) was an American investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. He launched a series of articles in McClure's, called "Tweed Days in St. Louis",[1] that would later be published together in a book titled The Shame of the Cities. He is remembered for investigating corruption in municipal government in American cities and for his leftist values.

Early life[]

Steffens was born in San Francisco, California, the only son and eldest of four children of Elizabeth Louisa (Symes) Steffens and Joseph Steffens. He was raised largely in Sacramento, the state capital; the Steffens family mansion, a Victorian house on H Street bought from merchant Albert Gallatin in 1887, would become the California Governor's Mansion in 1903.[2]

Steffens attended the Saint Matthew's Episcopal Day School, where he frequently clashed with the school's founder and director, stern disciplinarian, .[3]

Career[]

Steffens began his journalism career at the New York Commercial Advertiser in the 1890s,[4] before moving to the New York Evening Post. He later became an editor of McClure's magazine, where he became part of a celebrated muckraking trio with Ida Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker.[5] He specialized in investigating government and political corruption, and two collections of his articles were published as The Shame of the Cities (1904) and The Struggle for Self-Government (1906). He also wrote The Traitor State (1905), which criticized New Jersey for patronizing incorporation. In 1906, he left McClure's, along with Tarbell and Baker, to form The American Magazine. In The Shame of the Cities, Steffens sought to bring about political reform in urban America by appealing to the emotions of Americans. He tried to provoke outrage with examples of corrupt governments throughout urban America.

From 1914 to 1915 he covered the Mexican Revolution and began to see revolution as preferable to reform. In March 1919, he accompanied William C. Bullitt, a low-level State Department official, on a three-week visit to Soviet Russia and witnessed the "confusing and difficult" process of a society in the process of revolutionary change. He wrote that "Soviet Russia was a revolutionary government with an evolutionary plan", enduring "a temporary condition of evil, which is made tolerable by hope and a plan."[6]

After his return, he promoted his view of the Soviet Revolution and in the course of campaigning for U.S. food aid for Russia made his famous remark about the new Soviet society: "I have seen the future, and it works", a phrase he often repeated with many variations.[7] The title page of his wife Ella Winter's Red Virtue: Human Relationships in the New Russia (Victor Gollancz, 1933) carries this quote.

His enthusiasm for communism soured by the time his memoirs appeared in 1931. The autobiography became a bestseller leading to a short return to prominence for the writer, but Steffens would not be able to capitalize on it as illness cut his lecture tour of America short by 1933. He was a member of the California Writers Project, a New Deal program.

He married the twenty-six-year-old socialist writer Leonore (Ella) Sophie Winter in 1924 and moved to Italy, where their son Peter was born in San Remo. Two years later they relocated to the largest art colony on the Pacific Coast, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. Ella and Lincoln soon became controversial figures in the leftist politics of the region.[8] When John O’Shea, one of the local artists and a friend of the couple, exhibited his study of "Mr. Steffens’ soul", an image which resembled a grotesque daemon, Lincoln took a certain cynical pride in the drawing and enjoyed the publicity it generated.[9][10]

In 1934, Steffens and Winters helped found the San Francisco Workers' School (later the California Labor School); Steffens also served there as an advisor.

Death[]

Steffens died of a heart condition[11] on August 9, 1936, in Carmel, California.[11]

In 2011 Kevin Baker of The New York Times lamented that "Lincoln Steffens isn’t much remembered today".[12]

Works[]

- Pittsburgh is Hell with the Lid Off (1903) (Painting Jules Guerin/Lincoln Steffens)

- The Shame of the Cities (1904), online at the Internet Archive

- The Traitor State (1905)

- The Struggle for Self-Government (1906), online at the Internet Archive

- Upbuilders (1909), online at the Internet Archive

- The least of these: a fact story (1910), online at the Internet Archive

- Into Mexico and --Out! (1916), online at the Internet Archive

- Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens (1931)

In popular culture[]

Lincoln Steffens is mentioned in the Danny Devito movie "Jack the Bear" (1993).

Lincoln Steffens is mentioned in the 1987 novel The Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe.[13]

Characters on the American crime drama series City on a Hill, which debuted in 2019, make numerous references to Lincoln Steffens.[14][15]

The "Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens" is the favorite book of one of the members of The Group in Mary McCarthy's 1963 novel.[16]

References[]

- ^ Newman, John; Schmalbach, John (2015). United States History (2015 ed.). Amsco. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-7891-8904-2.

- ^ Steffens, Lincoln (1931). The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens. ISBN 9781597140164.

- ^

"Matters Historical: Military-style academies on the march in 1800s". East Bay Times. 2016-08-03. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

On at least one occasion, after being caught drinking while encouraging younger cadets to engage in such “forbidden activities,” Steffens was locked into Brewer’s guardhouse, where he existed in solitary confinement on limited rations for 22 days.

- ^ "American Characters: Lincoln Steffens | AMERICAN HERITAGE". www.americanheritage.com. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- ^ "On the Making of Same McClure's Magazine". McClure's Magazine. XXIV (1). November 1904. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Hartshorn, 304-11

- ^ Hartshorn, 315

- ^ Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 231, 233, 524, 548, 554–556, 558, 627, 682–683. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-29. Retrieved 2016-06-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)).

- ^ The Carmelite: 8 September 1932, p. 4; 20 October 1932, p.4.

- ^ The Oakland Tribune, 19 February 1933, p. 2-A.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lincoln Steffens, First Muckraker Dies At 70". Associated Press. August 10, 1936. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ^ Baker, Kevin (2011-05-13). "Lincoln Steffens: Muckraker's Progress". The New York Times.

- ^ Wolfe, Tom (June 21, 2018). The Bonfire of the Vanities. Random House. ISBN 9781473563926 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Review: Cop drama 'City On A Hill' finds Ben Affleck and Matt Damon's Boston is no beacon". Los Angeles Times. 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ "The Sneaky Greatness of Showtime's City On A Hill". pastemagazine.com. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ McCarthy, Mary (1963). The Group. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 154. ISBN 0-15-137281-0.

Further reading[]

Primary[]

- Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens (NY: Harcourt, Brace, 1958)

- The Letters of Lincoln Steffens, edited by Ella Winter and Granville Hicks, 2 vols. (1938)

Secondary[]

- Christopher Lasch, The American Liberals and the Russian Revolution (NY: Columbia University Press, 1962)

- Justin Kaplan, Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (NY: Simon and Schuster, 1974)

- Stanley K. Schultz, "The Morality of Politics: The Muckrakers' Vision of Democracy," The Journal of American History, vol. 52, no. 3. (December 1965), 527–547, in JSTOR

- Peter Hartshorn, I Have Seen the Future: A Life of Lincoln Steffens (Counterpoint, 2011)

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism (Simon & Schuster, 2013)

- Stephanie Gorton, Citizen Reporters: S. S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine that Rewrote America. New York: Ecco/HarperCollins, 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lincoln Steffens. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lincoln Steffens |

- "Joseph Lincoln Steffens". Journalist, Muckraker. Find a Grave. January 1, 2001.

- Lincoln Steffens' collected journalism at The Archive of American Journalism

- 1866 births

- 1936 deaths

- American autobiographers

- American male journalists

- Journalists from California

- American political writers

- American male writers

- American investigative journalists

- Writers from Sacramento, California

- Progressive Era in the United States

- Reform in the United States

- University of California, Berkeley alumni

- Writers about the Soviet Union

- People from Carmel-by-the-Sea, California

- Activists from California

- Anti-corruption activists