List of German inventions and discoveries

"What the world is today, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage, … for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favored."

American writer Mark Twain (1835−1910)[1]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Germany |

|---|

|

| Festivals |

|

German inventions and discoveries are ideas, objects, processes or techniques invented, innovated or discovered, partially or entirely, in Germany or abroad by a person from Germany (that is, someone born in Germany – including to non-German parents – or born abroad with at least one German parent and who had the majority of their education or career in Germany). Often, things discovered for the first time are also called inventions and in many cases, there is no clear line between the two.

Germany has been the home of many famous inventors, discoverers and engineers, including Carl von Linde, who developed the modern refrigerator;[2] Paul Nipkow, who laid the foundation of the television with his Nipkow disk;[3] Hans Geiger, the creator of the Geiger counter; and Konrad Zuse, who built the first fully automatic digital computer (Z3) and the first commercial digital computer (Z4).[4][5] Such German inventors, engineers and industrialists as Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin,[6] Otto Lilienthal, Gottlieb Daimler, Rudolf Diesel, Hugo Junkers and Karl Benz helped shape modern automotive and air transportation technology. Aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun developed the first space rocket at Peenemünde and later on was a prominent member of NASA and developed the Saturn V Moon rocket. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz's work in the domain of electromagnetic radiation was pivotal to the development of modern telecommunication.[7]

Albert Einstein introduced the special relativity and general relativity theories for light and gravity in 1905 and 1915 respectively. Along with Max Planck, he was instrumental in the introduction of quantum mechanics, in which Werner Heisenberg and Max Born later made major contributions.[8] Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays.[9] Otto Hahn was a pioneer in the fields of radiochemistry and discovered nuclear fission, while Ferdinand Cohn and Robert Koch were founders of microbiology.

The movable-type printing press was invented by German blacksmith Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. In 1997, Time Life magazine picked Gutenberg's invention as the most important of the second millennium.[10] In 1998, the A&E Network ranked Gutenberg as the most influential person of the second millennium on their "Biographies of the Millennium" countdown.[10]

The following is a list of inventions, innovations or discoveries known or generally recognised to be German.

Anatomy

- 17th century: First description of duct of Wirsung by Johann Georg Wirsung[11]

- 1720: Discovery of the ampulla of Vater by Abraham Vater[12]

- 1745: First description of crypts of Lieberkühn by Johann Nathanael Lieberkühn[13]

- 19th century: First description of Auerbach's plexus by Leopold Auerbach[14]

- 19th century: First description of Meissner's plexus by Georg Meissner[15]

- 19th century: Discovery of Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system by Theodor Schwann[16]

- 1836: Discovery and study of pepsin by Theodor Schwann[17]

- 1840: First medical report on poliomyelitis (Heine-Medin disease), and the first to recognize the illness as a clinical entity, by Jakob Heine[18]

- 1852: First description of tactile corpuscle by Georg Meissner and Rudolf Wagner[19]

- 1868: Discovery of Langerhans cell by Paul Langerhans[20]

- 1869: Discovery of islets of Langerhans by Paul Langerhans[21]

- 1875: First description of Merkel cell by Friedrich Sigmund Merkel[22]

- 1882: First successful cholecystectomy by Carl Langenbuch in Berlin[23]

- 1906: Discovery of the Alzheimer's disease by Alois Alzheimer[24]

- 1909: First description of Brodmann's areas by Korbinian Brodmann[25]

- 1977: Plastination by Gunther von Hagens[26]

Animals

- 1907: Modern zoo (Tierpark Hagenbeck) by Carl Hagenbeck in Hamburg[27]

- 1916: Guide dog; the world's first training school, established by Dr. Gerhard Stalling in Oldenburg[28]

Archaeology

- 1825: Rhamphorhynchus by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring[29]

- 1834: Plateosaurus by Johann Friedrich Engelhardt near Nuremberg, described in 1837 by Hermann von Meyer[30]

- 1856: Neanderthal 1 near Düsseldorf[31]

- 1856–1857: First description of the Neanderthal by Johann Carl Fuhlrott and Hermann Schaaffhausen[32]

- 1860: Teratosaurus by Sixt Friedrich Jakob von Kapff near Stuttgart, described in 1861 by Hermann von Meyer[33]

- 1861: Archaeopteryx by Hermann von Meyer near Solnhofen[34]

- 1868–1879: Troy by Heinrich Schliemann[35]

- c. 1900: Gordium by Alfred and Gustav Körte[36]

- 1906–1913: Hattusa by Hugo Winckler[37]

- 1908: Homo heidelbergensis by Daniel Hartmann and Otto Schoetensack near Heidelberg[38]

- 1912: The Nefertiti Bust by Ludwig Borchardt[39]

- 1915: Description of Spinosaurus, the largest known theropod, by Ernst Stromer[40]

- 1925: Stomatosuchus by Ernst Stromer[41]

- 1931: Description of Carcharodontosaurus by Ernst Stromer[42]

- 1932: Aegyptosaurus by Ernst Stromer[43]

- 1934: Bahariasaurus by Ernst Stromer[44]

- 1991: Ötzi by Helmut and Erika Simon from Nuremberg[45]

Arts

- 15th century: Drypoint by the Housebook Master, a south German artist[46]

- 1525: Ray tracing by Albrecht Dürer[47]

- 1642: Mezzotint by Ludwig von Siegen[48]

- 1708: Meissen porcelain, the first European hard-paste porcelain, by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus in Meissen[49]

- 1810: Theory of Colours by Johann Wolfgang Goethe[50]

- Early 1900s: The modernist movement Expressionism[51]

- 1919: Bauhaus by Walter Gropius[52]

Astronomy

- 1609–1619: Kepler's laws of planetary motion by Johannes Kepler[53]

- 1781: Discovery of Uranus, with two of its major moons (Titania and Oberon), by German-born William Herschel[54]

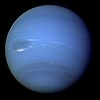

- 1846: Discovery of Neptune by Johann Galle[55]

- 1902: Discovery of the stratosphere by Richard Assmann[56]

- 1909: Discovery of cosmic ray by Theodor Wulf[57]

- 1916: Schwarzschild metric[58] and Schwarzschild radius[59] by Karl Schwarzschild

Biology, genetics and memory

- 1759: Description of mesonephros by Caspar Friedrich Wolff[60]

- 1790s: Recapitulation theory by Johann Friedrich Meckel and Carl Friedrich Kielmeyer[61]

- Late 1790s/early 1800s: Humboldtian science by Alexander von Humboldt[62]

- 1834: Humboldt penguin by Franz Meyen, after its initial discovery by Alexander von Humboldt[63]

- 1835: Cell division by Hugo von Mohl[64]

- 1835: Discovery and description of mitosis by Hugo von Mohl[65]

- 1839: Cell theory by Theodor Schwann and Matthias Jakob Schleiden (with contributions from Rudolf Virchow)[66]

- 1840: Discovery of hemoglobin by Friedrich Ludwig Hünefeld[67]

- 1845: Odic force by Carl Reichenbach[68]

- 1851: Discovery of alternation of generations as a general principle in plant life by Wilhelm Hofmeister[69]

- 1876: Discovery and description of meiosis by Oscar Hertwig[70]

- 1877: Description of dyslexia by Adolf Kussmaul[71]

- 1880s: Bacteriology by Robert Koch[72]

- Late 19th century: Isolated the non-protein component of "nuclein", determining the chemical composition of nucleic acids, and later isolated its five primary nucleobases by Albrecht Kossel[73]

- 1885: Forgetting curve and learning curve by Hermann Ebbinghaus[74]

- 1888: Description and naming of the centrosome by Theodor Boveri[75]

- 1890: Description of mitochondrion by Richard Altmann[76]

- 1892: Weismann barrier and germ plasm by August Weismann[77]

- 1908: Hardy–Weinberg principle by Wilhelm Weinberg[78]

- 1928: First reliable pregnancy test by Selmar Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek[79]

- 1928: Artificial cloning of organisms by Hans Spemann and Hilde Mangold[80]

- 1932: Urea cycle by Kurt Henseleit and Hans Adolf Krebs[81]

- 1937: Citric acid cycle by Hans Adolf Krebs[82]

- 1974: First genetically modified animal (a mouse) by Rudolf Jaenisch[83]

Chemistry

- 1625: Glauber's salt by German-born Johann Rudolf Glauber[84]

- 1669: Discovery of phosphorus by Hennig Brand in Hamburg[85]

- 1706: Prussian blue by Heinrich Diesbach in Berlin[86]

- 1724: Temperature scale Fahrenheit by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit[87]

- 1746: Basic theory of isolating zinc by Andreas Marggraf[88]

- c. 1770 – c. 1785: Identification of molybdenum, tungsten, barium and chlorine by Carl Wilhelm Scheele[89]

- 1773 or earlier: discovery of oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first) by Carl Wilhelm Scheele[90]

- 1789: Discovery of the elements uranium[91] and zirconium[92] by Martin Heinrich Klaproth

- 1799: Production of sugar from sugar beets, the beginning of the modern sugar industry,[93] by Franz Karl Achard, after foundations were laid by Andreas Marggraf[94]

- 19th century: Eupione by Carl Reichenbach[95]

- 1817: Discovery of cadmium by Karl Samuel Leberecht Hermann and Friedrich Stromeyer[96]

- 1820s: Oechsle scale by Ferdinand Oechsle[97]

- 1823: Döbereiner's lamp, often hailed as the first lighter,[98][99] by Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner

- 1828: Discovery of creosote by Carl Reichenbach[100]

- 1828, 1893: Isolation (1828) of nicotine by Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and Karl Ludwig Reimann.[101] The structure (1893) of nicotine was later discovered by Adolf Pinner and Richard Wolffenstein[102]

- 1828: Synthesis of urea by Friedrich Wöhler (Wöhler synthesis)[103]

- 1830: Creation of paraffin wax by Carl Reichenbach[104]

- 1832: Discovery of pittacal by Carl Reichenbach[105]

- 1834: Melamine by Justus von Liebig[106]

- 1834: Discovery of phenol by Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge[107]

- 1836 (or 1837): Discovery of diatomaceous earth (Kieselgur in German) by Peter Kasten on the northern slopes of the Haußelberg hill, in the Lüneburg Heath in North Germany[108]

- 1838: Fuel cell by Christian Friedrich Schönbein[109]

- 1839: Discovery of ozone by Christian Friedrich Schönbein[110]

- 1839, 1930: Discovery of polystyrene by Eduard Simon, was made a commercial product by IG Farben in 1930[111]

- c. 1840: Nitrogen-based fertiliser by Justus von Liebig,[112][113] important innovations were later made by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch (Haber process) in the 1900s[114]

- 1846: Discovery of guncotton by Christian Friedrich Schönbein[115]

- 1850s: Siemens-Martin process by Carl Wilhelm Siemens[116]

- c. 1855: Bunsen burner by Robert Bunsen and Peter Desaga[117]

- 1855: Chromatography by Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge[118]

- 1857: Siemens cycle by Carl Wilhelm Siemens[119]

- 1859: Pinacol coupling reaction by Wilhelm Rudolph Fittig[120]

- 1860–61: Discovery of caesium and rubidium by Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff[121]

- 1860: Erlenmeyer flask by Emil Erlenmeyer[122]

- 1863–64: Discovery of indium by Ferdinand Reich and Hieronymous Theodor Richter[123][124][125]

- 1863: First synthesis of trinitrotoluene (TNT) by Julius Wilbrand[126]

- 1864: First synthesis of barbiturate by Adolf von Baeyer, first marketed by Bayer under the name "Veronal" in 1903[127]

- 1865: Synthetic indigo dye by Adolf von Baeyer, first marketed by BASF in 1897[128]

- c. 1870: Brix unit by Adolf Brix[129]

- 1872: Synthesis of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) by Eugen Baumann[130]

- 1877: Poly(methyl methacrylate) by Wilhelm Rudolph Fittig, was made a commercial product (Plexiglas) by Otto Röhm in 1933[131]

- 1882: Tollens' reagent by Bernhard Tollens[132]

- 1883: Claus process by Carl Friedrich Claus[133]

- 1884: Paal–Knorr synthesis by Carl Paal and Ludwig Knorr[134]

- 1885–1886: Discovery of germanium by Clemens Winkler[135]

- 1887: Petri dish by Julius Richard Petri[136]

- 1888: Büchner flask and Büchner funnel by Ernst Büchner[137]

- 1895: Hampson–Linde cycle by Carl von Linde[119]

- 1897: Galalith by Wilhelm Krische[138]

- 1898: Polycarbonate by Alfred Einhorn, was made an commercial product by Hermann Schnell at Bayer in 1953 in Uerdingen[139]

- 1898: Synthesis of polyethylene, the most common plastic, by Hans von Pechmann[140]

- 1898: First synthesis of purine by Emil Fischer. He had also coined the word in 1884.[141]

- Early 20th century: Schlenk flask by Wilhelm Schlenk[142]

- 1900s: Haber process by Carl Bosch and Fritz Haber[114]

- 1902: Ostwald process by Wilhelm Ostwald[143]

- 1903: First commercially successful decaffeination process by Ludwig Roselius (later of Café HAG), after foundations were laid by Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge in 1820[144]

- 1907: Thiele tube by Johannes Thiele[145]

- 1913: Coal liquefaction (Bergius process) by Friedrich Bergius[146][147]

- 1913: Identification of protactinium by Oswald Helmuth Göhring[148]

- 1925: Discovery of rhenium by Otto Berg, Ida Noddack and Walter Noddack[149]

- 1928: Diels–Alder reaction by Kurt Alder and Otto Diels[150]

- 1929: Discovery of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by Karl Lohmann[151]

- 1929: Creation of styrene-butadiene (synthetic rubber) by Walter Bock[152]

- 1935: Karl Fischer titration by Karl Fischer[153]

- 1937: Creation of polyurethane by Otto Bayer at IG Farben in Leverkusen[154]

- 1953: Ziegler–Natta catalyst by Karl Ziegler[155]

- 1954: Wittig reaction by Georg Wittig[156]

- 1981–1996: Discovery and creation of bohrium by Peter Armbruster and Gottfried Münzenberg at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt[157]

- 1982: Discovery and creation of meitnerium at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research[158]

- 1984: Discovery and creation of hassium at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research[157]

- 1994: Discovery and creation of darmstadtium at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research[159]

- 1994: Discovery and creation of roentgenium at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research[160]

- 1996: Discovery and creation of copernicium at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research[161]

Clothing, cosmetics and fashion

- 13th century: Functional buttons with buttonholes for fastening or closing clothes[162]

- 18th century or earlier: Dirndl, Lederhosen and Tracht[163]

- 1709: Eau de Cologne by Johann Maria Farina (Giovanni Maria Farina) in Cologne[164]

- 1871–1873: Jeans by German-born Levi Strauss (together with Russian-American Jacob Davis)[165]

- 1905: Permanent wave that was suitable for use on people, by German-born Karl Nessler[166]

- 1911: Nivea, the first modern cream,[167] by Beiersdorf AG[168]

- 1960s: BB cream by Christine Schrammek[169]

Computing

- Late 17th century: Modern binary numeral system by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz[170]

- 1918–1923: Enigma machine by Arthur Scherbius[171]

- 1920s: Hellschreiber (precursor of the impact dot matrix printers and faxes) by Rudolf Hell[172][173]

- 1941: First programmable, fully automatic digital computer (Z3) by Konrad Zuse[174]

- 1942–1945: Programming language Plankalkül, the first high-level programming language to be designed for a computer,[175] by Konrad Zuse

- 1945: The world's first commercial digital computer (Z4) by Konrad Zuse[5]

- 1957: Stack (abstract data type) by Klaus Samelson and Friedrich L. Bauer of Technical University Munich[176]

- 1960s: Smart card by Jürgen Dethloff and Helmut Gröttrup[177]

Construction, architecture and shops

- 1831–1834: Wire rope by Wilhelm Albert[178][179][180]

- 1858: Hoffmann kiln by Friedrich Hoffmann[181][182]

- 1880: The world's first electric elevator by Werner von Siemens[183]

- 1895: Electrically driven hand drill by Carl and Wilhelm Fein in Stuttgart[184]

- 1895: Exothermic welding process by Hans Goldschmidt[185]

- 1926–1927: Portable electric (by Andreas Stihl in 1926 in Cannstatt) and the first petrol chainsaw (by Emil Lerp in 1927).[186] A precursor of chainsaws was made around 1830 by Bernhard Heine (osteotome)[187]

- 1927: Concrete pump by Max Giese and Fritz Hull[188]

- 1930s: Particle board by Max Himmelheber[189]

- 1954: Angle grinder by Ackermann + Schmitt (FLEX-Elektrowerkzeuge GmbH) in Steinheim an der Murr[190][191]

- 1958: Modern (plastic) wall plug (Fischer Wall Plug) by Artur Fischer[192][193][194]

- 1962: The world's first sex shop by Beate Uhse AG in Flensburg[195]

- 1963–1967: First hydraulic breaker by Krupp in Essen[196]

- 1988–1990: The concept of the Passivhaus (Passive house) standard by Wolfgang Feist in Darmstadt[197]

Cuisine

- Altbier

- Angostura bitters by Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert in Venezuela, 1824[198]

- First automat restaurant (Quisisana) in Berlin, 1895[199]

- Baumkuchen

- Modern beer – Reinheitsgebot[200][201] and "developing the beverage [beer] to its highest perfection"[202]

- Berliner (doughnut)

- Bethmännchen

- Berliner Weisse

- Bienenstich

- Black Forest cake

- Bock

- Bratwurst

- Braunschweiger

- Currywurst by Herta Heuwer[203]

- Dominostein by Herbert Wendler[204]

- Donauwelle

- Modern doner kebab sandwich in Berlin, 1972[205]

- Dortmunder Export

- Fanta

- Frankfurter Kranz

- Frankfurter Würstchen

- Gummy bear

- Hamburger (the "founder" is unknown, but it has German origins)[206][207]

- Hamburg steak

- Hedgehog slice (Kalter Hund)

- Helles

- Hot Dog[208][209]

- Jägermeister

- Kölsch

- Lager[210]

- Lebkuchen

- Marmite by Justus von Liebig[211][212]

- Märzen

- Meat extract by Justus von Liebig[213]

- Obatzda

- Parboiled rice (Huzenlaub Process) by Erich Gustav Huzenlaub[214]

- Pilsener by Josef Groll[215][216]

- Pinkel

- Potato salad (Kartoffelsalat)[217][218]

- Pretzel (the origin is disputed, but the earliest recorded evidence of pretzels appeared in Germany)[219]

- Prinzregententorte

- Pumpernickel

- Radler

- Riesling wine[220]

- Rye beer

- Saumagen

- Schwarzbier

- Sprite[221]

- Strammer Max

- Stollen

- Streuselkuchen

- Teewurst

- Thuringian sausage

- Toast Hawaii

- Welf pudding

- Wheat beer

- Zwieback

- Zwiebelkuchen

Education, language and printing

- 12th century: Lingua Ignota, the first entirely artificial language, by St. Hildegard of Bingen, OSB[222]

- c. 1440: Printing press with movable type by Johannes Gutenberg[10]

- 1605: First newspaper (Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien) by Johann Carolus in Strasbourg (then part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation)[223]

- 1774: The process of deinking by Justus Claproth[224]

- 1796: Lithography by Alois Senefelder[225]

- Early 19th century: Humboldtian model of higher education by Wilhelm von Humboldt,[226] which led to the creation of the first modern university (Universität zu Berlin) in 1810,[227] although the University of Halle is also regarded as "the first truly modern university"[228]

- 1812–1858: Grimms' Fairy Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm[229]

- 1830s: Kindergarten concept by Friedrich Fröbel[230]

- 1844: Wood pulp process for use in papermaking by Friedrich Gottlob Keller[231]

- 1879–80: The constructed language Volapük by Johann Martin Schleyer[232]

- 1884–1886: Linotype machine by Ottmar Mergenthaler[233]

- 1905: The Morse code distress signal SOS ( ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ )[234][235]

- 1919: Waldorf education by Emil Molt and Rudolf Steiner in Stuttgart[236]

- 1937–1951: Interlingua by German-born Alexander Gode[237]

Entertainment, electronics and media

- c. 1151: The earliest known morality play (Ordo Virtutum) by St. Hildegard of Bingen, OSB[238]

- 1505: The world's first (pocket) watch (Watch 1505) by Peter Henlein[239][240]

- 1663: First magazine (Erbauliche Monaths Unterredungen)[241]

- 1885: Nipkow disk (fundamental component in the earliest televisions) by Paul Gottlieb Nipkow[3]

- 1895: First moving picture show to a paying audience, and thereby creating the first cinema, by Emil and Max Skladanowsky in the Berlin Wintergarten theatre[242]

- 1897: Cathode-ray tube (CRT) and the oscilloscope by Ferdinand Braun[243]

- 1903: Printed circuit board by Albert Hanson of Berlin[244]

- 1907: Earplug by Max Negwer (Ohropax)[245]

- 1907: Pigeon photography by Julius Neubronner[246]

- 1920s: Small format camera (35mm format) by Oskar Barnack[247]

- 1928: Magnetic tape in Dresden, later developed and commercialized by AEG[248]

- 1930s: (Modern) tape recorder by BASF (then part of the chemical giant IG Farben) and AEG in cooperation with the state radio RRG[249][250]

- 1934: Fernsehsender Paul Nipkow (TV Station Paul Nipkow) in Berlin, first public television station in the world[251][252]

- 1949: Integrated circuit by Werner Jacobi (Siemens AG)[253][254]

- 1961: Phase Alternating Line (PAL), a colour encoding system for analogue television, by Walter Bruch of Telefunken in Hanover[255]

- 1970: Twisted nematic field effect by Wolfgang Helfrich (with Swiss physicist Martin Schadt)[256]

- 1983: Controller Area Network (CAN bus) by Robert Bosch GmbH[257]

- 1984: Short Message Service (SMS) concept by Friedhelm Hillebrand[258]

- Late 1980s and early 1990s: MP3 compression algorithm (fundamental for MP3 players) by i.a. Karlheinz Brandenburg (Fraunhofer Society)[259]

- 1990: First radio-controlled wristwatch (MEGA 1) by Junghans[260]

- 1991: SIM card by Giesecke & Devrient in Munich[261][262]

- 2005: YouTube by German-born Jawed Karim (together with Steve Chen and Chad Hurley)[263]

Geography, geology and mining

- 1812: Mohs scale of mineral hardness by Friedrich Mohs[264]

- 1855: Stauroscope by Wolfgang Franz von Kobell[265]

- 1884: Köppen climate classification by Wladimir Köppen.[266] Changes were later made by Rudolf Geiger (it is thus sometimes hailed as the "Köppen–Geiger climate classification system").[267]

- 1912: Theory of continental drift and postulation of the existence of Pangaea by Alfred Wegener[268]

- 1933: Central place theory by Walter Christaller[269]

- 1935: Richter magnitude scale by German-born Beno Gutenberg (together with Charles Francis Richter)[270]

Household and office appliance

- 19th century: Meat grinder by Karl Drais[271]

- 1835: Modern (silvered-glass) mirror by Justus von Liebig[272][273][274]

- 1864: Ingrain wallpaper by Hugo Erfurt[275]

- 1870–1895: Modern refrigerator and modern refrigeration by Carl von Linde.[2][276][277][278]

- 1871: Modern mattress (the innerspring mattress) by Heinrich Westphal in Berlin[279][280]

- 1886: Hole punch and ring binder by Friedrich Soennecken in Bonn[281]

- 1886: Folding ruler by Anton Ullrich in Maikammer[282]

- 1901: Adhesive tape by company Beiersdorf AG[283]

- 1907: (Modern) Laundry detergent (Persil) by Henkel[284]

- 1908: Paper coffee filter by Melitta Bentz[285]

- 1909: Egg slicer by Willy Abel in Berlin[286]

- 1929, 1949: First machine-produced tea bag (1929) and the modern tea bag (1949) by Adolf Rambold and Teekanne[287][288]

- 1930s: Ink eraser by Pelikan[289]

- 1941: Chemex Coffeemaker by German-born Peter Schlumbohm[290]

- 1954: Wigomat, the first electrical drip coffee maker[291]

- 1969: Glue stick by Henkel[292]

Mathematics

- 1611: Kepler conjecture by Johannes Kepler[293]

- 1623: Mechanical calculator by Wilhelm Schickard[294][295]

- Late 17th century: Calculus[296] and Leibniz's notation[297] by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

- 1673–1676: Leibniz formula for π by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz[298]

- 1675: Integral symbol by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz[299]

- 1795: Least squares by Carl Friedrich Gauss[300]

- c. 1810: Gaussian elimination by Carl Friedrich Gauss[301]

- 1824: Generalization of the Bessel function by Friedrich Bessel[302]

- 1827: Gauss map[303] and Gaussian curvature[304] by Carl Friedrich Gauss

- 1837: Analytic number theory by Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet[305]

- c. 1850: Riemann geometry by Bernhard Riemann[306]

- 1859: Riemann hypothesis by Bernhard Riemann[307]

- 1874: Cantor's first uncountability proof and set theory by Georg Cantor[308]

- 1882: Klein bottle by Felix Klein[309]

- 1891: Cantor's diagonal argument and Cantor's theorem by Georg Cantor[310]

- 1897: Cantor–Bernstein–Schroeder theorem by Felix Bernstein and Ernst Schröder[311]

- c. 1900: Runge–Kutta methods by Wilhelm Kutta and Carl Runge[312][313]

- 1900s: Hilbert space by David Hilbert[314]

- Early 20th century: Weyl tensor by Hermann Weyl[315]

Medicine and drugs

- 1796: Homeopathy by Samuel Hahnemann[316]

- 1803–1827: First isolation of morphine by Friedrich Sertürner in Paderborn; first marketed to the general public by Sertürner and Company in 1817 as a pain medication; and the first commercial production began in 1827 in Darmstadt by Merck.[317]

- 1832: First synthesis of chloral hydrate, the first hypnotic drug,[318] by Justus von Liebig at the University of Giessen;[319] Oscar Liebreich introduced the drug into medicine in 1869 and discovered its hypnotic and sedative qualities.[320]

- 1840: Discovery and description of Graves-Basedow disease by Karl Adolph von Basedow[321]

- 1847: Kymograph by Carl Ludwig[322]

- 1850s: Microscopic pathology by Rudolf Virchow[323]

- 1850–51: Ophthalmoscope by Hermann von Helmholtz[324][325]

- 1852: First complete blood count by Karl von Vierordt[326]

- 1854: Sphygmograph by Karl von Vierordt[327]

- 1855: First synthesis of the cocaine alkaloid by Friedrich Gaedcke;[328] development of an improved purification process by Albert Niemann in 1859–1860, who also coined the name "cocaine".[329] First commercial production of cocaine began in 1862 in Darmstadt by Merck.[330]

- 1882: Adhesive bandage (Guttaperchapflastermulle) by Paul Carl Beiersdorf[331]

- 1882: Discovery of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) bacteria which causes tuberculosis, by Robert Koch[332]

- 1884: Discovery of the pathogenic bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae which causes diphtheria, by Edwin Klebs and Friedrich Löffler[333]

- 1884: Koch's postulates by Robert Koch and Friedrich Loeffler, based on earlier concepts described by Jakob Henle[334]

- 1884: Discovery of the vibrio cholerae bacteria which causes cholera, by Robert Koch[335]

- 1887: Amphetamine by Romanian-born Lazăr Edeleanu in Berlin[336]

- 1887: Löffler's medium by Friedrich Loeffler[337]

- 1888: First successful afocal scleral glass contact lenses by Adolf Gaston Eugen Fick[338]

- 1890: Diphtheria antitoxin by Emil von Behring[339]

- 1897–1899: Aspirin by Felix Hoffmann or Arthur Eichengrün at Bayer in Elberfeld[340]

- 1897: Heroin by Felix Hoffmann at Bayer in Elberfeld[341]

- 1897: Protargol by Arthur Eichengrün.[342]

- 1897: Discovery of the cause of foot-and-mouth disease (Aphthovirus) by Friedrich Loeffler[343]

- 1907–1910: First synthesis of arsphenamine, the first antibiotic,[344] by Paul Ehrlich and Alfred Bertheim.[345] In 1910 marketed by Hoechst under the name Salvarsan.[346]

- 1908–1911: Creation of dihydrocodeine[347]

- 1909, 1929: First intrauterine device (IUD) by Richard Richter (of Waldenburg, then part of Germany; in 1909), and the first ring (Gräfenberg's ring, 1929) used by a significant number of women by Ernst Gräfenberg.[348]

- 1909: Labello by Dr. Oscar Troplowitz[349]

- 1912–1916: Modern condom by Julius Fromm in Berlin[350]

- 1912: MDMA by Merck chemist Anton Köllisch[351][352]

- 1914: Development and creation of oxymorphone[353]

- 1916: Creation of oxycodone by Martin Freund and Edmund Speyer at the University of Frankfurt[354]

- 1920–1924: First synthesis of hydrocodone by Carl Mannich and Helene Löwenheim in 1920,[355] first marketed by former German drug development company Knoll as Dicodid in 1924.[356]

- 1922: Discovery and creation of desomorphine by Knoll[357]

- 1923: Creation of hydromorphone (Dilaudid) by Knoll[358]

- 1924: First human electroencephalography (EEG) recording by Hans Berger. He also invented the electroencephalogram and discovered alpha waves.[359]

- 1929: Cardiac catheterization by Werner Forssmann[360]

- 1932: Prontosil by Josef Klarer and Fritz Mietzsch at Bayer[361]

- 1937–1939: Creation of methadone by Max Bockmühl and Gustav Ehrhart of IG Farben[362]

- 1939: Intramedullary rod by Gerhard Küntscher[363]

- 1943: Luria–Delbrück experiment by Max Delbrück[364]

- 1953: Echocardiography by Carl Hellmuth Hertz (with Swedish physician Inge Edler)[365]

- 1961: Combined oral contraceptive pill by Schering AG[366][367]

- 1969: Articaine (Ultracain), a dental local anesthetic first synthesized by pharmacologist and chemist (former Hoechst AG)[368][369]

- 1997: C-Leg by Ottobock[370]

- 2007: Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) by Walter Sekundo and Marcus Blum[371]

- 2020: mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) based on research by Turkey-born Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci[372][373]

Military and (chemical) weapons

- 1498: Barrel rifling in Augsburg[374]

- 1836: Dreyse needle gun by Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse[375]

- 1842: Pickelhaube by King Frederick William IV of Prussia[376]

- 1901: Modern flamethrower by Richard Fiedler[377]

- 1916: First anti-tank grenade[378]

- 1916: Stahlhelm by Dr. Friedrich Schwerd[379]

- 1918: First anti-tank rifle (Mauser 1918 T-Gewehr) by Mauser[380]

- 1918: First practical submachine gun (MP 18) by Theodor Bergmann[381]

- 1920s: Creation of Zyklon B by Walter Heerdt and Bruno Tesch at Degesch[382]

- 1935: Flecktarn by Johann Georg Otto Schick[383]

- 1935–37: Jerrycan by Müller & Co in Schwelm[384]

- 1936: The first ever nerve agent, tabun, by Gerhard Schrader (IG Farben) in Leverkusen[385][386]

- 1938: The nerve agent sarin by IG Farben in Wuppertal-Elberfeld[387]

- 1939: Warfare method of blitzkrieg by i.a. Heinz Guderian[388][389]

- 1941: The only rocket-powered fighter aircraft ever to have been operational and the first piloted aircraft of any type to exceed 1000 km/h (621 mph) in level flight, the Messerschmitt Me 163, by Alexander Lippisch.[390]

- 1942: First modern assault rifle (StG 44) by Hugo Schmeisser[391]

- 1943: First aviation unit (Kampfgeschwader 100) to use precision-guided munition[392]

- c. 1944: First anti-tank missile (the X-7)[393]

- 1944: First operational cruise missile (V-1 flying bomb) by Robert Lusser at Fieseler[394]

- 1944: A modern pioneer and the world's first long-range guided ballistic missile (V-2 rocket) under the direction of Wernher von Braun[395][396]

- 1944: The nerve agent soman by Konrad Henkel in Heidelberg[397]

Musical instruments

- c. 1700: Clarinet by Johann Christoph Denner in Nuremberg[398][399]

- 1805: Panharmonicon by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel[400]

- 1814–1816: Metronome by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel and Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel[401]

- 1818: (Modern) French horn by Heinrich Stölzel and Friedrich Blühmel[402]

- 1821: Harmonica by Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann[403]

- 1828: Flugelhorn by Heinrich Stölzel in Berlin[404]

- 1830 or earlier: Accordion in Nuremberg[405]

- 1835: Tuba by Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht and Johann Gottfried Moritz in Berlin[406]

- 1850s: Wagner tuba by Richard Wagner[407]

- 1854: Bandoneon by Heinrich Band[408]

- 1877: Microphone by Emile Berliner[409][410]

- 1887: Gramophone record by Emile Berliner[410][411]

- 1914: Hornbostel–Sachs, the most used system in musical instrument classification, by Curt Sachs (together with Erich Moritz von Hornbostel)[412]

Physics and scientific instruments

- 1512, 1576: Theodolite by Gregorius Reisch and Martin Waldseemüller (1512),[413] although the first "true" version was created by Erasmus Habermehl (1576)[414]

- 1608: Telescope by German-born Hans Lippershey[415]

- 1650: First vacuum pump by Otto von Guericke[416]

- 1654: Magdeburg hemispheres by Otto von Guericke[417]

- 1663: First electrostatic generator by Otto von Guericke[418]

- 1745: Leyden jar (Kleistian jar) by Ewald Georg von Kleist[419]

- 1777: Discovery of Lichtenberg figures by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg[420]

- 1801: Discovery of ultraviolet by Johann Wilhelm Ritter[421]

- 1813: Gauss's law by Carl Friedrich Gauss[422]

- 1814: Discovery of Fraunhofer lines by Joseph von Fraunhofer[423]

- 1817: Ackermann steering geometry by Georg Lankensperger in Munich[424][425]

- 1817 or earlier: Gyroscope by Johann Gottlieb Friedrich von Bohnenberger in Tübingen[426]

- 1820: Galvanometer by Johann Schweigger in Halle[427]

- 1827: Ohm's law by Georg Ohm[428]

- 1833: Magnetometer by Carl Friedrich Gauss[429]

- 1845: Kirchhoff's circuit laws by Gustav Kirchhoff[430]

- 1850: Formulation of the first and second law of thermodynamics by Rudolf Clausius[431][432]

- 1852: First experimental investigation of the Magnus effect by Heinrich Gustav Magnus[433]

- 1857: Geissler tube by Heinrich Geißler[434]

- 1959: Helmholtz resonance by Hermann von Helmholtz[435]

- 1859: Spectrometer by Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff[436]

- 1861: First telephone transmitter by Johann Philipp Reis;[437][438] he also coined the term "telephone"[438]

- 1864–1875: Centrifuge by brothers Alexander and Antonin Prandtl from Munich[439]

- 1865: Concept of entropy by Rudolf Clausius[440]

- 1869: First observation of cathode rays by Johann Wilhelm Hittorf and Julius Plücker[441]

- 1870: Virial theorem by Rudolf Clausius[442]

- 1874: Refractometer by Ernst Abbe[443][444]

- 1883: First accurate electricity meter (Pendelzähler) by Hermann Aron[445]

- 1886: Discovery of anode rays by Eugen Goldstein[446]

- 1887: Discoveries of electromagnetic radiation, photoelectric effect and radio waves by Heinrich Hertz[447]

- 1887: First parabolic antenna by Heinrich Hertz[448]

- 1893–1896: Wien approximation (1896)[449] and Wien's displacement law (1893)[450] by Wilhelm Wien

- 1895: Discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in Würzburg[451]

- 1897: Nernst lamp by Walther Nernst in Göttingen[452]

- 1900: Drude model by Paul Drude[453]

- 1900: Planck constant and Planck's law by Max Planck[454]

- 1900–1930: Quantum mechanics by i.a. Max Planck and Werner Heisenberg[455]

- 1901: Modern pyrometer by Ludwig Holborn and Ferdinand Kurlbaum[456]

- 1904: Boundary layer theory by Ludwig Prandtl[457]

- 1904: First radar system by Christian Hülsmeyer (Telemobiloscope)[458]

- 1905: Mass–energy equivalence (E = mc2)[459] and special relativity[460] by Albert Einstein

- 1905: Rubens' tube by Heinrich Rubens[461]

- 1906–1912: Third law of thermodynamics (Nernst's theorem) by Walther Nernst[462]

- 1913: Echo sounding by Alexander Behm[463][464]

- 1913: Discovery of the Stark effect by Johannes Stark[465]

- 1915: Noether's theorem by Emmy Noether[466]

- 1916: General relativity by Albert Einstein[467]

- 1917: Laser's theoretical foundation by Albert Einstein[468]

- 1919: Discovery of the Barkhausen effect by Heinrich Barkhausen[469]

- 1919: Betz's law by Albert Betz[470]

- 1920s: (Modern) hand-held metal detector by German-born Gerhard Fischer[471]

- 1921: Discovery of nuclear isomerism by Otto Hahn[472]

- 1921–22: Stern–Gerlach experiment by Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach[473]

- 1924: Description of coincidence method by Walther Bothe[474]

- 1924–25: Bose–Einstein statistics, Bose–Einstein condensate and Boson by Albert Einstein[475]

- 1927: Free electron model by Arnold Sommerfeld[476]

- 1927: Uncertainty principle by Werner Heisenberg[477]

- 1928: Geiger–Müller counter by Hans Geiger and Walther Müller[478]

- 1931: Electron microscope by Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll[479]

- 1933: Discovery of the Meissner effect by Walther Meissner and Robert Ochsenfeld[480]

- 1937–39: CNO cycle (Bethe–Weizsäcker process) by Carl von Weizsäcker and German-born Hans Bethe[481]

- 1937: Scanning electron microscope (SEM) by Manfred von Ardenne[482]

- 1938: Discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann in Berlin[483][484]

- 1949: Development of the nuclear shell model by Maria Goeppert-Mayer and J. Hans D. Jensen[485]

- 1950s: Quadrupole ion trap by Wolfgang Paul[486]

- 1958: Discovery of the Mössbauer effect by Rudolf Mössbauer[487]

- 1959: Penning trap by Hans Georg Dehmelt[488]

- 1961: Bark scale by Eberhard Zwicker[489]

- 1963: Proposition of heterojunction by Herbert Kroemer[490]

- 1980: Quantum Hall effect by Klaus von Klitzing[491]

- 1980s: Atomic force microscope and the scanning tunneling microscope by Gerd Binnig[492][493]

- 1988: Discovery of giant magnetoresistance by Peter Grünberg[494]

- 1994: STED microscopy by Stefan Hell and Jan Wichmann[495]

- 1998: Frequency comb by Theodor W. Hänsch[496]

Sociology, philosophy and politics

- Late 18th century: German idealism by Immanuel Kant[497]

- 19th century: Marxism, the foundation of communism and socialism,[498][499] by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels[500]

- 1852: Credit union by Franz Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch in Saxony, later further developed by Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen[501]

- Late 19th century: Verstehen by Max Weber[502]

- 1879: Psychology by Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig[503][504]

- 1880s: The German Empire (1871–1918) became the first modern welfare state in the world under statesman Otto von Bismarck,[505] when he e.g. innovatively implemented the following:

- 1897: Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, first LGBT rights organization in history,[507][508] founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin

- 1916: The German Empire became the first country in the world to implement daylight saving time (DST)[509]

- 1930s: Critical theory by the Frankfurt School[510]

- 1966: Private copying levy (also known as blank media tax or levy)[511]

- 1978: Blue Angel (Der Blaue Engel) certification, the world's first ecolabel[512]

Religion, ethics and festivities

- 1434: The world's first genuine Christmas market (Striezelmarkt) in Dresden[513]

- 1517: Protestantism and Lutheranism by Martin Luther[514]

- 16th century: Modern Christmas tree[515][516]

- 17th century: Easter Bunny[517]

- c. 1610: Tinsel in Nuremberg[518]

- 1776: Illuminati by Adam Weishaupt[519]

- 1810: Oktoberfest, the world's largest Volksfest,[520] in Munich

- 1839: Advent wreath by Johann Hinrich Wichern[521]

- c. 1850: Advent calendar by German Lutherans;[522] the modern version was created by Gerhard Lang (1881–1974) from Munich[523]

Sport

- c. 1790: Balance beam by Johann Christoph Friedrich GutsMuths[524]

- c. 1810: Horizontal bar, parallel bars, rings and the vault apparatus by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who is often hailed as the "father of modern gymnastics"[525][526][527]

- 1901: Modern bodybuilding by Eugen Sandow[528]

- 1906: Schutzhund, a dog sport that tests a dog's tracking[529]

- c. 1910: Loop jump in figure skating by Werner Rittberger[530]

- 1917–1919: Handball by Max Heiser, Karl Schelenz, and Erich Konigh in Berlin[531][532]

- 1920: Gliding by Oskar Ursinus[533]

- 1925: Wheel gymnastics by Otto Feick in Schönau an der Brend[534]

- 1936: The tradition of the Olympic torch relay by Carl Diem and Alfred Schiff in Berlin[535]

- 1946: Goalball by Sepp Reindle[536]

- 1948: Paralympic Games by German-born Ludwig Guttmann[537][538]

- 1954: Modern football boots with screw-in studs by Adolf (Adidas) or Rudolf Dassler (Puma)[539]

- 1961: Underwater rugby by Ludwig von Bersuda in Cologne[540]

- 1963: Grass skiing by Josef Kaiser[541][542]

- 1970: Penalty shoot-out in football by Karl Wald[543]

- 1989: International Paralympic Committee in Düsseldorf[544]

- 1993: Jugger in Heidelberg[545]

- 2000: Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters (DTM)[546]

- 2001: Speed badminton by Bill Brandes in Berlin[547]

Tourism and recreation

- 1882: Strandkorb by Wilhelm Bartelmann in Rostock[548][549]

- 1891: First purpose-built cruise ship (Prinzessin Victoria Luise) by Albert Ballin[550]

- Early 20th century: Pilates by Joseph Pilates[551]

- 1911: Carabiner for climbing by Otto "Rambo" Herzog[552]

- 1915 or earlier: Modern parachute (the first collapsible parachute) by Katharina Paulus[553][554]

- 1920s: Autogenic training by Johannes Heinrich Schultz[555]

Toys and games

- c. 1780: Schafkopf card game[556]

- c. 1810: Skat card game in Altenburg[557]

- 1890: Plastilin by Franz Kolb[558]

- 1892: Chinese checkers by Ravensburger[559]

- 1902: Teddy bear (55 PB) by Richard Steiff[560]

- 1907–08: Mensch ärgere Dich nicht board game by Josef Friedrich Schmidt[561]

- 1964: fischertechnik by Artur Fischer[562]

- 1972: First home video console (Magnavox Odyssey) by German-born Ralph H. Baer[563][564]

- 1974: Playmobil by Hans Beck[565]

- 1995: The Settlers of Catan by Klaus Teuber[566]

Transportation

- 1655: First self-propelled wheelchair by Stephan Farffler[567]

- 1817: The first bicycle (dandy horse, or Laufmaschine in German) by Baron Karl von Drais[568][569]

- 1817: Tachometer by Diedrich Uhlhorn[570][571]

- 1834: First practical rotary electric motor by Moritz von Jacobi[572]

- 1838: First electric boat by Moritz von Jacobi[573]

- 1876: Otto engine, the first modern internal combustion engine,[574] by Nicolaus Otto

- 1879–1881: First electric locomotive[575] and electric tramway (Gross-Lichterfelde Tramway) by Siemens & Halske[576][577]

- 1882: Trolleybus (Electromote) by Werner von Siemens[578]

- 1885: First automobile (Benz Patent-Motorwagen) by Karl Benz in Mannheim[579][580]

- 1885, 1894: First motorcycle (Daimler Reitwagen) by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach.[581] The motorcycle of Hildebrand & Wolfmüller from 1894 (created by Heinrich and Wilhelm Hildebrand, and Alois Wolfmüller) was the first machine to be called a "motorcycle" and the world's first production motorcycle.[582]

- 1886: First automobile on four wheels, by Gottlieb Daimler[583]

- 1886: Motorboat by Lürssen, in commission of Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, in Bremen[584]

- 1888: Driver's license by Karl Benz[585]

- 1888: The world's first filling station was the city pharmacy in Wiesloch[586]

- 1888: Flocken Elektrowagen, regarded by some as the first real electric car,[587] by Andreas Flocken in Coburg

- 1889: V engine by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach[588]

- 1891: Taximeter by Friedrich Wilhelm Gustav Bruhn[589]

- 1893: Diesel engine, diesel fuel and biodiesel by Rudolf Diesel in Augsburg[590]

- 1893: Lilienthal Normalsegelapparat, the first aeroplane to be serially produced,[591][592] by Otto Lilienthal

- 1893: Zeppelin, the first rigid airship,[593] by Ferdinand von Zeppelin[594]

- 1895: Internal combustion engine bus by Daimler[595]

- 1896: First truck (Daimler Motor-Lastwagen) by Gottlieb Daimler[596]

- 1897: Flat engine by Karl Benz[597]

- 1897: Internal combustion engine taxicab by Gottlieb Daimler[598]

- 1901: Mercedes 35 hp, regarded by some as the first real modern automobile,[599] by Paul Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach. The car also had the world's first drum brakes.[600]

- 1902, 1934: Concept of maglev by Alfred Zehden (1902) and Hermann Kemper (1934).[601]

- 1902: First high voltage spark plug by Gottlob Honold[602]

- 1902: First practical speedometer by Otto Schultze[603][604]

- 1906: Gyrocompass by Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe[605]

- 1909, 1912: The world's first passenger airline; DELAG in Frankfurt (1909).[606] The company also employed the first flight attendant, Heinrich Kubis (1912).[607]

- 1912: The world's first diesel locomotive by Gesellschaft für Thermo-Lokomotiven Diesel-Klose-Sulzer GmbH from Munich[608] and Borsig from Berlin[609]

- 1915: The world's first all-metal aircraft (Junkers J 1) by Junkers & Co[610]

- 1916: Gasoline direct injection (GDI) by Junkers & Co[611]

- 1928: First rocket-powered aircraft (Lippisch Ente) by Alexander Lippisch[612]

- 1935: Swept wing by Adolf Busemann[613]

- 1936: The first operational and practical helicopter (Focke-Wulf Fw 61), by Focke-Achgelis[614]

- 1939: First aircraft with a turbojet (Heinkel He 178), and the first practical jet aircraft, by Hans von Ohain[615]

- 1943: Krueger flap by Werner Krüger[616]

- 1951: Airbag by Walter Linderer[617]

- 1957: Wankel engine by Felix Wankel[618]

- 1960s: Defogger by Heinz Kunert[619]

- Late 1960s: Oxygen sensor by Robert Bosch GmbH[620]

- 1973: Spoiler on road cars by Porsche[621]

- 1995: Electronic stability control (ESC) by Robert Bosch GmbH and Mercedes-Benz[622][623]

See also

- German inventors and discoverers

- List of German chemists

- List of German mathematicians

- List of German physicists

- List of German scientists

- Science and technology in Germany

References

- ^ Childress, Diana (2008). Johannes Gutenberg and the Printing Press. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7613-4024-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carl von Linde". Science History Institute. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bellis, Mary (6 April 2017). "Television History - Paul Nipkow". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Bianchi, Luigi. "The Great Electromechanical Computers". York University. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kaisler, Stephen H. (2016). Birthing the Computer: From Relays to Vacuum Tubes. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 9781443896313.

- ^ "The Zeppelin". U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Historical figures in telecommunications". International Telecommunication Union. 14 January 2004. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Roberts, J. M. (2002). The New Penguin History of the World. Allen Lane. p. 1014. ISBN 978-0-7139-9611-1.

- ^ "The First Nobel Prize". Deutsche Welle. 8 September 2010. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Die Gutenbergstadt Mainz". Gutenberg.de. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Johann Georg Wirsung". www.whonamedit.com. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Dissertatio anatomica quo novum bilis dicetilicum circa orifucum ductus choledochi ut et valvulosam colli vesicæ felleæ constructionem ad disceptandum proponit, 1720

- ^ "Johann Nathanael Lieberkühn". www.whonamedit.com. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Leopold Auerbach". www.whonamedit.com. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Meissner, G. (1857). "Über die Nerven der Darmwand". Zeitschrift für rationelle Medizin. 8: 364–366.

- ^ Karenberg, Axel (26 October 2000). "Chapter 7. The Schwann cell". In Koehler, Peter J.; Bruyn, George W.; Pearce, John M. S. (eds.). Neurological eponyms. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–50. ISBN 9780195133660. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1980). A short history of biology. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780313225833.

- ^ "History of polio". BBC News. 25 September 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Meissner, G.; Wagner, R. (February 1852). "Ueber das Vorhandensein bisher unbekannter eigenthümlicher Tastkörperchen (Corpuscula tactus) in den Gefühlswärzchen der mensclichen Haut und über die Endausbreitung sensitiver Nerven". Nachrichten von der Georg-Augusts-Universität und der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. 2: 17–30.

- ^ Langerhans, P. (1868). "Ueber die Nerven der menschlichen Haut". Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin. 44 (2–3): 325–337. doi:10.1007/BF01959006. S2CID 6282875.

- ^ Sakula, A. (July 1988). "Paul Langerhans (1847–1888): a centenary tribute". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 81 (7): 414–5. doi:10.1177/014107688808100718. PMC 1291675. PMID 3045317.

- ^ Merkel, F. S. (1875). "Tastzellen und Tastkörperchen bei den Hausthieren und beim Menschen". Archiv für mikroskopische Anatomie. 11: 636–652. doi:10.1007/BF02933819. S2CID 83793552.

- ^ Jarnagin, William R; Belghiti, J; Blumgart, LH (2012). Blumgart's surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas (5th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4557-4606-4.

- ^ Berchtold, N. C.; Cotman, C. W. (1998). "Evolution in the conceptualization of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: Greco-Roman period to the 1960s". Neurobiology of Aging. 19 (3): 173–89. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(98)00052-9. PMID 9661992. S2CID 24808582.

- ^ Brodmann K. Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrinde. Leipzig : Johann Ambrosius Bart, 1909

- ^ "The Developments of Plastination". Body Worlds. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Rothfels, Nigel (2008). Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo (Animals, History, Culture). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801889752.

- ^ "International Guide Dog Federation - History". www.igdf.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Witton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. p. 123. ISBN 9781400847655.

- ^ von Meyer, C. E. H. (1837). "Mitteilung an Prof. Bronn (Plateosaurus engelhardti)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. 1837: 316.

- ^ King, W. (1864). "The Reputed Fossil Man of the Neanderthal" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Science. 1: 88–97.

- ^ Drell, J. R. R. (2002). "Neanderthals: a history of interpretation". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 19: 1–24. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00096.

- ^ von Meyer, C. E. H. (1861). "Reptilien aus dem Stubensandstein des oberen Keupers". Palaeontographica. 7: 253–346.

- ^ Meyer, Hermann von (15 August 1861). "Vogel-Federn und Palpipes priscus von Solenhofen" [Bird feathers and Palpipes priscus [a crustacean] from Solenhofen]. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde (in German): 561. "Aus dem lithographischen Schiefer der Brüche von Solenhofen in Bayern ist mir in den beiden Gegenplatten eine auf der Ablösungs- oder Spaltungs-Fläche des Gesteins liegende Versteinerung mitgetheilt worden, die mit grosser Deutlichkeit eine Feder erkennen lässt, welche von den Vogel-Federn nicht zu unterscheiden ist." (From the lithographic slates of the faults of Solenhofen in Bavaria, there has been reported to me a fossil lying on the stone's surface of detachment or cleavage, in both opposing slabs, which can be recognized with great clarity [to be] a feather, which is indistinguishable from a bird's feather.)

- ^ Schuchhardt, Carl (1891). Schliemann's Ausgrabungen in Troja, Tiryns, Mykenae, Orchomenos, Ithaka im Lichte der heutigen Wissenschaft. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus.

- ^ Körte, A.; Körte, G. (1904). Gordion: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabung im Jahre 1900. Berlin: Verlag Georg Reimer.

- ^ Elborough, Travis (2019). Atlas of Vanishing Places: The lost worlds as they were and as they are today. White Lion Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 9781781318959.

- ^ Schoetensack, Otto (1908). Der Unterkiefer des Homo heidelbergensis aus den Sanden von Mauer bei Heidelberg. Ein Beitrag zur Paläontologie des Menschen. Leipzig: Verlag Wilhelm Engelmann.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (6 December 2012). "The Bust of Nefertiti: Remembering Ancient Egypt's Famous Queen". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Stromer, E. (1915). "Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharije-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). 3. Das Original des Theropoden Spinosaurus aegyptiacus nov. gen., nov. spec". Abhandlungen der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-physikalische Klasse. 28: 1–32.

- ^ Stromer, E. (1925). "Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharije-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). 7. Stomatosuchus inermis Stromer, ein schwach bezahnter Krokodilier und 8. Ein Skelettrest des Pristiden Onchopristis numidus Haug sp". Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung. 30: 1–22.

- ^ Stromer, E. (1931). "Wirbeltiere-Reste der Baharijestufe (unterestes Canoman). Ein Skelett-Rest von Carcharodontosaurus nov. gen". Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung. 9: 1–23.

- ^ Stromer, E. (1932). "Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltierreste der Baharîje-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). 11. Sauropoda". Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung. Neue Folge. 10: 1–21.

- ^ Stromer, E. (1934). "Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltier-Reste der Baharije-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman)." 13. Dinosauria". Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung n.f. 22: 1–79.

- ^ Squires, Nick (29 September 2008). "Oetzi The Iceman's discoverers finally compensated". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Explaining the Drypoint Etching". Widewalls. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Hofmann, Georg Rainer (May 1990). "Who invented ray tracing?". The Visual Computer. 6 (3): 120–124. doi:10.1007/BF01911003. S2CID 26348610.

- ^ "Ludwig van Siegen Invents Mezzotint". www.historyofinformation.com. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ The Discovery of European Porcelain Technology by C.M. Queiroz & S. Agathopoulos, 2005.

- ^ Goethe's Theory of Colours: Translated from the German; with Notes by Charles Lock Eastlake, R.A., F.R.S. London: John Murray. 1840. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Expressionism Movement Overview". The Art Story. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 319.

- ^ Holton, Gerald James; Brush, Stephen G. (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure: From Copernicus to Einstein and Beyond (3rd paperback ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-8135-2908-0. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ "Herschel Program - Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel". www.astroleague.org. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Hamilton, Calvin J. (4 August 2001). "Neptune". Views of the Solar System. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Steinhagen, Hans (2005). Der Wettermann - Leben und Werk Richard Aßmanns. Neuenhagen: Findling. ISBN 978-3-933603-33-3.

- ^ Hörandel, J. R. (4 December 2012). "Early Cosmic-Ray Work Published in German". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1516: 52–60. arXiv:1212.0706. doi:10.1063/1.4792540. S2CID 73534390.

- ^ Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 7: 189–196. Bibcode:1916SPAW.......189S.

- ^ Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Über das Gravitationsfeld einer Kugel aus inkompressibler Flussigkeit nach der Einsteinschen Theorie". Sitzungsberichte der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Klasse für Mathematik, Physik, und Technik: 424. Bibcode:1916skpa.conf..424S.

- ^ Fritz, Marc A.; Speroff, Leon (2005). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 325. ISBN 9780781747950.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (1994). "Recapitulation Reinterpreted: The Somatic Program". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 69 (2): 223–232. doi:10.1086/418541. S2CID 84670449.

- ^ Böhme, H. (1999). "Ästhetische Wissenschaft". Matices: 37–41.

- ^ McCarthy, Eugene M. "Humboldt Penguin - Online Biology Dictionary". www.macroevolution.net. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Rogers, Kara (2011). The Cell. Britannica Educational Pub. p. 172. ISBN 978-1615303144.

- ^ von Mohl, Hugo (1835). Ueber die Vermehrung der Pflanzenzellen durch Theilung. Tübingen: Fues.

- ^ Sharp, L. W. (1921). Introduction To Cytology. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company Inc.

- ^ Hünefeld F.L. (1840). "Die Chemismus in der thierischen Organization". Leipzig.

- ^ Levitt, Theresa (2009). The Shadow of Enlightenment: Optical and Political Transparency in France, 1789-1848. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-19-954470-7.

- ^ Svedelius, N. (1927). "Alternation of Generations in Relation to Reduction Division". Botanical Gazette. 83 (4): 362–384. doi:10.1086/333745. S2CID 84406292.

- ^ Ruvinsky, Anatoly (2009). Genetics and Randomness. CRC Press. p. 93. ISBN 9781420078879.

- ^ Beaton, Alan (2004). Dyslexia, Reading and the Brain: A Sourcebook of Psychological and Biological Research. Psychology Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781135422752.

- ^ "Robert Koch (1843-1910)". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ "SEEKS LIFE'S SECRET IN STUDY OF CELLS; Prof. Albrecht Kossel of Heidelberg Comes to Lecture at Johns Hopkins University". The New York Times. 27 August 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Ebbinghaus, Hermann (1885). Über das Gedächtnis. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

- ^ Boveri, Theodor (1888). Zellen-Studien II: Die Befruchtung und Teilung des Eies von Ascaris megalocephala. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag.

- ^ Altmann, Richard (1890). Die Elementarorganismen und ihre Beziehungen zu den Zellen. Leipzig: Veit.

- ^ Weismann, August (1892). Das Keimplasma: eine Theorie der Vererbung. Jena: Fischer.

- ^ Stern, Curt (1962). "Wilhelm Weinberg". Genetics. 47: 1–5.

- ^ Speert, Harold (1973). Iconographia Gyniatrica. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. ISBN 978-0-8036-8070-8.

- ^ De Robertis, EM (April 2006). "Spemann's organizer and self-regulation in amphibian embryos". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 7 (4): 296–302. doi:10.1038/nrm1855. PMC 2464568. PMID 16482093.

- ^ Bailey, L. E.; Ong, S. D. (1978). "Krebs–Henseleit solution as a physiological buffer in perfused and superfused preparations". Journal of Pharmacological Methods. 1 (2): 171–175. doi:10.1016/0160-5402(78)90022-0.

- ^ Krebs, H. A.; Johnson, W. A. (April 1937). "Metabolism of ketonic acids in animal tissues". The Biochemical Journal. 31 (4): 645–660. doi:10.1042/bj0310645. PMC 1266984. PMID 16746382.

- ^ Jaenisch, R.; Mintz, B. (April 1974). "Simian Virus 40 DNA Sequences in DNA of Healthy Adult Mice Derived from Preimplantation Blastocysts Injected with Viral DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (4): 1250–1254. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.1250J. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.4.1250. PMC 388203. PMID 4364530.

- ^ Szydlo, Zbigniew (1994). Water which does not wet hands: The Alchemy of Michael Sendivogius. London–Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-8386062454.

- ^ Beatty, Richard (2000). Phosphorus. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 7. ISBN 0-7614-0946-7.

- ^ Jens Bartoll. "The early use of prussian blue in paintings" (PDF). 9th International Conference on NDT of Art, Jerusalem Israel, 25–30 May 2008. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Balmer, Robert T. (2010). Modern Engineering Thermodynamics. Academic Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-12-374996-3.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1933). The Discovery of the Elements. Easton, Pennsylvania: Journal of Chemical Education. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7661-3872-8.

- ^ Lepora, Nathan (2007). Molybdenum. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 11. ISBN 9780761422013.

- ^ "Oxygen". www.rsc.org. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks: An A to Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 476–482. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ^ Krebs, Robert E. (1998). The History and Use of our Earth's Chemical Elements. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 978-0-313-30123-0.

- ^ Kent, James A. (2007). Kent and Riegel's Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology. Springer. p. 1658. ISBN 978-0387278421.

- ^ Sack, Harald (28 April 2016). "Franz Achard and the Sugar Beet Revolution". SciHi Blog. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Dunglison, Robley (1838). Dunglison's American medical library. A. Waldie. p. 192.

- ^ Hermann, C. S. (1818). "Noch ein schreiben über das neue Metall". Annalen der Physik. 59 (5): 113–116. Bibcode:1818AnP....59..113H. doi:10.1002/andp.18180590511.

- ^ "Oechsle, Christian Ferdinand (1774-1852) (in German)". Gesellschaft für Geschichte des Weines e.V. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Hoffmann, Roald (August 1998). "Döbereiner's Feuerzeug". American Scientist. 86. doi:10.1511/1998.4.326.

- ^ "Döbereiner's Lamp - History of the First Lighter". www.historyofmatches.com. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Schorlemmer, C. (1885). "The history of creosote, cedriret, and pittacal". Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry. 4: 152–157.

- ^ Henningfield, J. E.; Zeller, M. (March 2006). "Nicotine psychopharmacology research contributions to United States and global tobacco regulation: a look back and a look forward". Psychopharmacology. 184 (3–4): 286–291. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0308-4. PMID 16463054. S2CID 38290573.

- ^ Pinner, A. (1893). "Ueber Nicotin. Die Constitution des Alkaloïds". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 26: 292–305. doi:10.1002/cber.18930260165.

- ^ Wöhler, F. (1828). "Ueber künstliche Bildung des Harnstoffs". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 88 (2): 253–256. Bibcode:1828AnP....88..253W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280880206 – via Gallica.

- ^ Britannica (1911)

- ^ Graham, Thomas (2015). Elements of Chemistry: Including the Applications of the Science in the Arts. Palala Press. ISBN 978-1341237980.

- ^ Handbook on Textile Auxiliaries, Dyes and Dye Intermediates Technology. National Institute of Industrial Research. 2009. p. 82. ISBN 978-8178331225.

- ^ F. F. Runge (1834) "Ueber einige Produkte der Steinkohlendestillation" (On some products of coal distillation), Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 31 : 65-78. On page 69 of volume 31, Runge names phenol "Karbolsäure" (coal-oil-acid, carbolic acid). Runge characterizes phenol in: F. F. Runge (1834) "Ueber einige Produkte der Steinkohlendestillation," Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 32 : 308-328.

- ^ Klebs, Florian (December 17, 2001). "Deutschland - Wiege des Nobelpreis: Tourismus-Industrie und Forschung auf den Spuren Alfred Nobels" (in German). Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Archived from the original on November 17, 2002. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ Bührke, Thomas; Wengenmayr, Roland (2013). Renewable Energy: Sustainable Energy Concepts for the Energy Change. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9783527671366.

- ^ Rubin, Mordecai B. (2001). "The History of Ozone: The Schönbein Period, 1839–1868" (PDF). Bull. Hist. Chem. 26 (1): 40–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2019-12-22.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (24 January 2019). "The Long History of Polystyrene and Styrofoam". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Justus von Liebig: Feeding billions of people - Halfapage.com". Halfapage.com. 2015-08-23. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ^ Horn, Jeff (2016). The Industrial Revolution: History, Documents, and Key Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 978-1610698849.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harford, Tim (2 January 2017). "How fertiliser helped feed the world". BBC. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Bown, Stephen R. (2005). A Most Damnable Invention: Dynamite, Nitrates, and the Making of the Modern World. Macmillan. ISBN 9781466817050.

- ^ Siemens, C. W. (June 1862). "On a regenerative gas furnace, as applied to glasshouses, puddling, heating, etc". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 13: 21–26. doi:10.1243/PIME_PROC_1862_013_007_02.

- ^ Jensen, W. B. (2005). "The Origin of the Bunsen Burner". Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (4): 518. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82..518J. doi:10.1021/ed082p518.

- ^ Runge, F. F. (1855). Der Bildungstrieb der Stoffe, veranschaulicht in selbstständig gewachsenen Bilder. Oranienburg, Germany: self-published.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Technical Information". Kryolab. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Fittig, R. (1859). "Ueber einige Metamorphosen des Acetons der Essigsäure". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 110: 23–45. doi:10.1002/jlac.18591100104.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1861). "Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen" (PDF). Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 189 (7): 337–381. Bibcode:1861AnP...189..337K. doi:10.1002/andp.18611890702.

- ^ Erlenmeyer, E. (January 1860). "Zur chemischen und pharmazeutischen Technik". Zeitschrift für Chemie und Pharmacie. 3: 21–22.

- ^ Venetskii, S. (1971). "Indium". Metallurgist. 15 (2): 148–150. doi:10.1007/BF01088126.

- ^ Reich, F.; Richter, T. (1864). "Ueber das Indium". Journal für Praktische Chemie (in German). 92 (1): 480–485. doi:10.1002/prac.18640920180.

- ^ Schwarz-Schampera, Ulrich; Herzig, Peter M. (2002). Indium: Geology, Mineralogy, and Economics. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-43135-0.

- ^ Wilbrand, J. (1863). "Notiz über Trinitrotoluol". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 128 (2): 178–179. doi:10.1002/jlac.18631280206.

- ^ "Barbiturates". Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ "Cooperative Research - Formula for Success". BASF. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Figoni, Paula I. (2010). How Baking Works: Exploring the Fundamentals of Baking Science. John Wiley & Sons. p. 174. ISBN 9780470392676.

- ^ Baumann, E. (1872). "Ueber einige Vinylverbindungen". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 163 (3): 308–322. doi:10.1002/jlac.18721630303. hdl:2027/wu.89101101970.

- ^ "This is how PLEXIGLAS® came to be". World of Plexiglas. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Tollens, B. (1882). "Ueber ammon-alkalische Silberlösung als Reagens auf Aldehyd" [On an ammonical alkaline silver solution as a reagent for aldehydes]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 15 (2): 1635–1639. doi:10.1002/cber.18820150243.

- ^ Steudel, R.; West, L. (December 2015). "Carl Friedrich Claus (1827-1900) - inventor of the Claus Process for sulfur production from hydrogen sulfide". ResearchGate. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1712.2644.

- ^ Katritzky, Alan R. (2013). Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780124202092.

- ^ Winkler, Clemens (1887). "Germanium, Ge, a New Nonmetal Element" (English translation). Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 19 (1): 210–211. doi:10.1002/cber.18860190156.

- ^ Yahoo Education:Petri dish Archived 2013-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jensen, William B. (September 2006). "The Origins of the Hirsch and Büchner Vacuum Filtration Funnels" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 83 (9): 1283. Bibcode:2006JChEd..83.1283J. doi:10.1021/ed083p1283.

- ^ Trimborn, Christel. "Galalith - Jewelry Milk Stone". Ganoksin. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Hermann Schnell". Plastics Hall of Fame. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ von Pechmann, H. (1898). "Ueber Diazomethan und Nitrosoacylamine". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin. 31: 2640–2646.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1902". The Nobel Prize. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Royal Society of Chemistry :Classic Kit: Schlenk apparatus

- ^ GB 190208300, Ostwald, Wilhelm, "Improvements in and relating to the Manufacture of Nitric Acid and Oxides of Nitrogen", published December 18, 1902, issued February 26, 1903

- ^ "Decaffeination 101: Four Ways to Decaffeinate Coffee". Coffee Confidential. 6 July 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Thiele, J. (February 1907). "Ein neuer Apparat zur Schmelzpunktsbestimmung". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 40: 996–997. doi:10.1002/cber.190704001148.

- ^ Bergius, Friedrich (May 21, 1932). "Chemical reactions under high pressure" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ D. Valentin: Kohleverflüssigung - Chancen und Grenzen, Praxis der Naturwissenschaften, 1/58 (2009), S. 17-19.

- ^ Scerri, Eric (2013). A tale of seven elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 67–74. ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2.

- ^ Noddack, W.; Tacke, I.; Berg, O. (1925). "Die Ekamangane". Naturwissenschaften. 13 (26): 567–574. Bibcode:1925NW.....13..567.. doi:10.1007/BF01558746. S2CID 32974087.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1950". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Lohmann, K. (August 1929). "Über die Pyrophosphatfraktion im Muskel". Naturwissenschaften. 17 (31): 624–625. Bibcode:1929NW.....17..624.. doi:10.1007/BF01506215. S2CID 20328411.

- ^ "The Difference between Styrene-Butadiene Rubber and Styrene-Butadiene Latex". Mallard Creek Polymers. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Fischer, K. (1935). "Neues Verfahren zur maßanalytischen Bestimmung des Wassergehaltes von Flüssigkeiten und festen Körpern". Angew. Chem. 48 (26): 394–396. doi:10.1002/ange.19350482605.

- ^ DE 728981, IG Farben, published 1937

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1963". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Hoffmann, R. W. (2001). "Wittig and His Accomplishments: Still Relevant Beyond His 100th Birthday". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (8): 1411–1416. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1411::AID-ANIE1411>3.0.CO;2-U.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barber, R. C.; Greenwood, N. N.; Hrynkiewicz, A. Z.; Jeannin, Y. P.; Lefort, M.; Sakai, M.; Ulehla, I.; Wapstra, A. P.; Wilkinson, D. H. (1993). "Discovery of the transfermium elements. Part II: Introduction to discovery profiles. Part III: Discovery profiles of the transfermium elements". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (8): 1757. doi:10.1351/pac199365081757. S2CID 195819585.

- ^ Münzenberg, G.; Armbruster, P.; Heßberger, F. P.; Hofmann, S.; Poppensieker, K.; Reisdorf, W.; Schneider, J. H. R.; Schneider, W. F. W.; et al. (1982). "Observation of one correlated α-decay in the reaction 58Fe on 209Bi→267109". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 309 (1): 89. Bibcode:1982ZPhyA.309...89M. doi:10.1007/BF01420157. S2CID 120062541.

- ^ Karol, P. J.; Nakahara, H.; Petley, B. W.; Vogt, E. (2001). "On the discovery of the elements 110-112 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 73 (6): 959. doi:10.1351/pac200173060959. S2CID 97615948.

- ^ Hofmann, S.; Ninov, V.; Heßberger, F. P.; Armbruster, P.; Folger, H.; Münzenberg, G.; Schött, H. J.; Popeko, A. G.; et al. (1995). "The new element 111". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 350 (4): 281. Bibcode:1995ZPhyA.350..281H. doi:10.1007/BF01291182. S2CID 18804192.

- ^ Hofmann, S.; et al. (1996). "The new element 112". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 354 (3): 229–230. doi:10.1007/BF02769517. S2CID 119975957.

- ^ Lynn White: "The Act of Invention: Causes, Contexts, Continuities and Consequences", Technology and Culture, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Autumn, 1962), pp. 486–500 (497f. & 500)

- ^ "How German Traditions Work". HowStuffWorks. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Möderler, Catrin (13 July 2009). "Original eau de Cologne celebrates 300 years". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Who Made America? | Innovators | Levi Strauss". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ A Revolutionist Dies. LIFE Magazine. Vol. 30 no. 6. Time Inc. Feb 5, 1951. p. 37. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ Rähse, Wilfried (2019). Cosmetic Creams: Development, Manufacture and Marketing of Effective Skin Care Products. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9783527812431.

- ^ "Milestones". Beiersdorf. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Chang, Katie (29 March 2012). "Vain Glorious | BB Creams Are Here!". T Magazine. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Leibniz G., Explication de l'Arithmétique Binaire, Die Mathematische Schriften, ed. C. Gerhardt, Berlin 1879, vol.7, p.223; Engl. transl.[1]

- ^ Singh, Simon (2011). The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-78784-2.

- ^ "Rudolf Hell". The Independent. 2002-04-08. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ "HELL". www.cryptomuseum.com. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ "75 Years of the Z3, World's First Modern Computer". Inverse. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ Giloi, W. K. (1997). "Konrad Zuse's Plankalkül: The First High-Level "non von Neumann" Programming Language" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 19: 17–24. doi:10.1109/85.586068. S2CID 8657307. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-01-30.

- ^ "Friedrich L. Bauer, inventor of the stack and of the term software engineering". people.idsia.ch. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Chen, Zhiqun (2000). Java Card Technology for Smart Cards: Architecture and Programmer's Guide. Addison-Wesley Professional. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780201703290.

- ^ "Wilhelm Albert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Koetsier,Teun; Ceccarelli, Marc (2012). Explorations in the History of Machines and Mechanisms. Springer Publishing. p. 388. ISBN 9789400741324. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Donald Sayenga. "Modern History of Wire Rope". History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy (atlantic-cable.com). Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Heeney, Gwen (2003). Brickworks. A & C Black Publishers Ltd. p. 35. ISBN 9780812237825.

- ^ "Rings of fire: Hoffmann kilns". LOW-TECH MAGAZINE. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (11 August 2019). "The History of Elevators From Top to Bottom". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Bar-Cohen, Yoseph; Zacny, Kris (2009). Drilling in Extreme Environments: Penetration and Sampling on Earth and other Planets. John Wiley & Sons. p. 5. ISBN 9783527626632.

- ^ H. Goldschmidt, "Verfahren zur Herstellung von Metallen oder Metalloiden oder Legierungen derselben" (Process for the production of metals or metalloids or alloys of the same), Deutsche Reichs Patent no. 96317 (13 March 1895).

- ^ Thöny, Philip (12 December 2007). "The History of the Chainsaw". Waldwissen. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "History of the Chainsaw - Celebrating 60 Years". Husqvarna. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Cramer, Dietmar; Hesse, Daniela (2013). "Die Geschichte des Transportbetons (in German)". Unternehmensgeschichte und Unternehmenskultur. 9: 13.

- ^ "Die Spanplatte des Herrn Himmelheber | SWR Fernsehen". swr.online (in German). 9 June 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "History". Flex. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Schwarzmann, Thomas (2015). "Von der Flex zur Giraffe Erfinder des Winkelschleifers bringen neuen Langhalsschleifer heraus". Bauhandwerk (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Artur Fischer's plastic wall plug transforms construction industry". Financial Times. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ Office, European Patent. "Artur Fischer (Germany)". www.epo.org. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ "Uitvinder en pluggenkoning Arthur Fischer overleden". Historiek (in Dutch). 2016-01-29. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ Strebe, Amy Goodpaster; Beckman, Trish (2007). Flying for her country: the American and Soviet women military pilots of World War II. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-275-99434-1.

- ^ Sleight, Chris (1 October 2013). "Hydraulic breakers turn 50". KHL. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "The first Passive House: Interview with Dr. Wolfgang Feist". iPHA Blog. 19 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Hayes, Annie (5 October 2016). "Angostura: a brand history". The Spirits Business. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Smith, Andrew F. (2015). Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover's Companion to New York City. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0199397020.

- ^ Unger, Richard W. (1992). "Technical Change in the Brewing Industry in Germany, the Low Countries and England in the Late Middle Ages". www.jeeh.it. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ Kasko, Cyndie. "History German Beer | Reinheitsgebot | Oktoberfest Beer". www.oldworld.ws. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ Hart, James A. (1995). U.S. Business and Today's Germany: A Guide for Corporate Executives and Attorneys. Abc-Clio. p. 220. ISBN 9780899308395.

- ^ Paterson, Tony (15 August 2009). "Spicy sausage that is worthy of a shrine in Berlin". The Independent. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Dresdner Dominosteine". 2012-11-19. Archived from the original on 2012-11-19. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ "Doner kebab 'inventor' dies at 80". BBC. 26 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Where Did Hamburgers Originate?". Community Table. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ "How the Hamburger Became an American Favorite". Time. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ "frankfurter | Origin and meaning of frankfurter by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ "History of the Hot Dog: Such a Fantastic German Invention!". The Sausage Man. 2016-11-08. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ Watson, Mike (30 September 2012). "The History of Lager". Beer Expert. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "Ten things you'll love/hate to know about Marmite". BBC. 25 May 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2019.