List of most massive black holes

This is an ordered list of the most massive black holes so far discovered (and probable candidates), measured in units of solar masses (M☉), approximately 2×1030 kilograms.

Introduction

A supermassive black hole (SMBH) is an extremely large black hole, on the order of hundreds of thousands to billions of solar masses (M☉), and is theorized to exist in the center of almost all massive galaxies. In some galaxies, there are even binary systems of supermassive black holes, see the OJ 287 system. Unambiguous dynamical evidence for SMBHs exists only in a handful of galaxies;[1] these include the Milky Way, the Local Group galaxies M31 and M32, and a few galaxies beyond the Local Group, e.g. NGC 4395. In these galaxies, the mean square (or root mean square) velocities of the stars or gas rises as ~1/r near the center, indicating a central point mass. In all other galaxies observed to date, the rms velocities are flat, or even falling, toward the center, making it impossible to state with certainty that a supermassive black hole is present.[1] Nevertheless, it is commonly accepted that the center of nearly every galaxy contains a supermassive black hole.[2] The reason for this assumption is the M–sigma relation, a tight (low scatter) relation between the mass of the hole in the ~10 galaxies with secure detections, and the velocity dispersion of the stars in the bulges of those galaxies.[3] This correlation, although based on just a handful of galaxies, suggests to many astronomers a strong connection between the formation of the black hole and the galaxy itself.[2]

Although SMBHs are currently theorized to exist in almost all massive galaxies, more massive black holes are rare; with only fewer than several dozen having been discovered to date. There is extreme difficulty in determining the mass of a particular SMBH, and so they still remain in the field of open research. SMBHs with accurate masses are limited only to galaxies within the Laniakea Supercluster and to active galactic nuclei.

Another problem for this list is the method used in determining the mass. Such methods, such as broad emission-line reverberation mapping (BLRM), Doppler measurements, velocity dispersion, and the aforementioned M–sigma relation have not yet been well established. Most of the time, the masses derived from the given methods contradict each other's values.

This list contains supermassive black holes with known masses, determined at least to the order of magnitude. Some objects in this list have two citations, like 3C 273; one from Bradley M. Peterson et al. using the BLRM method,[4] and the other from Charles Nelson using [OIII]λ5007 value and velocity dispersion.[5] Note that this list is very far from complete, as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) alone detected 200000 quasars, which likely may be the homes of billion-solar-mass black holes. In addition, there are several hundred citations for black hole measurements not yet included on this list. Despite this, the majority of well-known black holes above 1 billion M☉ are shown. Messier galaxies with precisely known black holes are all included.

New discoveries suggest that many black holes, dubbed 'stupendously large', may exceed 100 billion or even 1 trillion solar masses.[6]

List

This list is incomplete; you can help by . (June 2017) |

Due to the very large numbers involved, listed black holes here have their mass values in scientific notation (numbers multiplied to powers of 10). Values with uncertainties are written in parentheses when possible. Note that different entries in this list have different methods and systematics in obtaining their mass values, and hence different levels of confidence in their masses. These methods are specified in their notes.

| Name | Solar mass (Sun = 1 × 100) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TON 618 | 6.6×1010[7] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. |

| Black hole of central elliptical galaxy of MS 0735.6+7421 | 5.13×1010[8][9] | Produced a colossal AGN outburst after accreting 600 million M☉ worth of material.

Estimated using the break radius of 0.5 kpc core of the central galaxy.[8][9] Previous indirect assumptions about the efficiencies of gas accretion and jet power yield a lower limit of 1 billion M☉.[10][11][12] |

| Holmberg 15A | (4.0±0.8)×1010[13] | Mass specified obtained through orbit-based, axisymmetric Schwarzschild models. Earlier estimates range from ~310 billion M☉ down to 3 billion M☉, all relying on empirical scaling relations and are thus obtained from extrapolation and not from kinematical measurements.[14] |

| IC 1101 | (4–10)×1010[15] | Estimated from properties of the host galaxy (Faber–Jackson relation); mass has not been measured directly. |

| S5 0014+81 | 4×1010[16][17][18] | A 2010 paper suggested that a funnel collimates the radiation around the jet axis, creating an optical illusion of very high brightness, and thus a possible overestimation of the black hole mass.[16] |

| SMSS J215728.21-360215.1 | (3.4±0.6)×1010[19] | Estimated using near-infrared spectroscopic measurements of the MgII emission line doublet. |

| SDSS J102325.31+514251.0 | (3.31±0.61)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. |

| H1821+643 | 3×1010[21] | Value obtained as an indirect estimate using a model of minimum Eddington luminosity required to account for the Compton cooling of the surrounding cluster.[21] |

| NGC 6166 | 3×1010[22] | Central galaxy of Abell 2199; notable for its hundred thousand light year long relativistic jet. |

| 2.7×1010[23] | Estimated using the full-width half maxima of the CIV emission line and monochromatic luminosity at 1350 Å wavelength. | |

| APM 08279+5255 | 2.3×1010[24] 1.0+0.17 −0.13×1010[25] |

Based on velocity width of CO line from orbiting molecular gas,[24] and reverberation mapping using SiIV and CIV emission lines.[25] |

| NGC 4889 | (2.1±1.6)×1010[26][27] | Best fit: the estimate ranges from 6 billion to 37 billion M☉.[26][27] |

| RBS 2043 | 2×1010[28] | Central galaxy of the Phoenix Cluster;[29] this black hole is continuously growing at the rate of ~60 M☉ per year. |

| (1.95±0.05)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

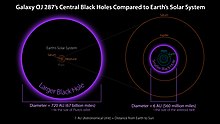

| OJ 287 primary | 1.8×1010[30] | A smaller 100 million M☉ black hole orbits this one in a 12-year period (see OJ 287 secondary below). But this measurement is in question due to the limited number and precision of observed companion orbits. |

| NGC 1600 | (1.7±0.15)×1010[31][32] | Unprecedentedly massive in relation of its location: an elliptical galaxy host in a sparse environment. |

| (1.51±0.31)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| (1.41±0.10)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| (1.38±0.03)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (1.35±0.22)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| Abell 1201 BCG | (1.3±0.6)×1010[33] | Estimated from the strong gravitational lensing of a background galaxy behind the BCG.[33] Beware of ambiguity between the BH mass determination and the galaxy cluster's dark matter profile.[34] |

| SDSS J0100+2802 | (1.24±0.19)×1010[35][36] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. This object grew early in cosmic history (redshift 6.30). |

| (1.20±0.06)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| NGC 1270 | 1.2×1010[37] | Elliptical galaxy located in the Perseus Cluster. Also is a low-luminosity AGN (LLAGN).[38] |

| (1.12±0.20)×1010[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line | |

| (1.1±0.2)×1010[39] | Estimated from accretion disk spectrum modelling.[39] | |

| PSO J334.2028+01.4075 | 1×1010[40] | There are actually two black holes, orbiting at each other in a close pair with a 542-day period. The largest one is quoted, while the smaller one's mass is not defined.[40] |

| Black hole of central elliptical galaxy of RX J1532.9+3021 | 1×1010[41] | |

| QSO B2126-158 | 1×1010[16] | |

| NGC 1281 | 1×1010[42] | Compact elliptical galaxy in the Perseus Cluster. Mass estimates range from 10 billion M☉ down to <5 billion M☉.[43] |

| (9.8±1.4)×109[20] | ||

| NGC 3842 | 9.7+3.0 −2.5×109[26][27] |

Brightest galaxy in the Leo Cluster |

| (9.12±0.88)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| 8×109[44] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| (7.8±3.9)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| 6.9+0.8 −1.2×109[45] |

Constitutes 10% of the total mass of its host galaxy. Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (6.46±0.45)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (6.31±1.16)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| Messier 87 | 7.22+0.34 −0.40×109[46] 6.3×109[47] |

Central galaxy of the Virgo Cluster; the first black hole directly imaged. |

| NGC 5419 | 7.2+2.7 −1.9×109[48] |

Estimated from the stellar velocity distribution. A secondary satellite SMBH may orbit around 70 parsecs.[48] |

| (5.25±0.73)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (5.13±0.71)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| QSO B0746+254 | 5×109[16] | |

| QSO B2149-306 | 5×109[16] | |

| (4.7±0.2)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| Messier 60 | (4.5±1.0)×109[49] | |

| (4.1±2.4)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| QSO B0222+185 | 4×109[16] | |

| Hercules A (3C 348) | 4×109 | Notable for its million light-year long relativistic jet. |

| Abell 1836-BCG | 3.61+0.41 −0.50×109[50] |

|

| (3.5±0.2)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (3.4±0.4)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| (3.1±0.6)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| NGC 1271 | 3.0+1.0 −1.1×109[51] |

Compact elliptical or lenticular galaxy in the Perseus Cluster.[52] |

| (3.0±0.4)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar MgII emission line correlation. | |

| QSO B0836+710 | 3×109[16] | |

| (2.63±1.21)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (2.4±0.50)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| (2.24±0.15)×109[20] | Estimated from quasar Hβ emission line correlation. | |

| 2.02×109[53] | ||

| ULAS J1120+0641 | 2×109[54][55] | |

| QSO 0537-286 | 2×109[16] | |

| NGC 3115 | 2×109[56] | |

| Q0906+6930 | 2×109[57] | Most distant blazar, at z = 5.47 |

| QSO B0805+614 | 1.5×109[16] | |

| Messier 84 | 1.5×109[58] | |

| J100758.264+211529.207 ("Pōniuāʻena") | (1.5±0.2)×109[59] | Second most-distant quasar known |

| 1.36×109[53] | ||

| Abell 3565-BCG | 1.34+0.21 −0.19×109[50] |

|

| 1.3+0.5 −0.4×109[27] |

||

| NGC 1277 | 1.2×109[60] | Once thought to harbor a black hole so large that it contradicted modern galaxy formation and evolutionary theories,[61] re-analysis of the data revised it downward to roughly a third of the original estimate.[62] and then one tenth.[60] |

| QSO B225155+2217 | 1×109[16] | |

| QSO B1210+330 | 1×109[16] | |

| Cygnus A | 1×109[63] | Brightest extrasolar radio source in the sky as seen at frequencies above 1 GHz |

| Sombrero Galaxy | 1×109[64] | Bolometrically most luminous galaxy in the local universe and also the nearest billion-solar-mass black hole to Earth. |

| Markarian 501 | 9×108–3.4×109[65] | Brightest object in the sky in very high energy gamma rays. |

| (1.298±0.385)×109[4] 467740000[5] |

||

| 3C 273 | (8.86±1.87)×108[4] 550000000[5] |

Brightest quasar in the sky |

| ULAS J1342+0928 | 8×108[66] | Most distant quasar[66] − currently on record as the most distant quasar at z=7.54[66] |

| Messier 49 | 5.6×108[67] | |

| ESO 444-46 | 5.01×108–7.76×1010[8][9] | Brightest cluster galaxy of Abell 3558 in the center of the Shapley Supercluster; estimated using spheroidal luminosity profile of the host galaxy. |

| NGC 1399 | 5×108[68] | Central galaxy of the Fornax Cluster |

| (6.93±0.83)×108[4] 190550000[5] |

||

| (5.94±1.38)×108[4] 275420000[5] |

||

| 7.81+1.82 −1.65×108[4] 60260000[5] |

||

| NGC 4261 | 4×108[69] | Notable for its 88000 light-year long relativistic jet.[70] |

| (4.4±1.23)×108[4] 281 840 000[5] |

||

| (3.5±0.8)×108[71][72] | Constitutes 1.4% of the mass of its host galaxy | |

| NGC 1275 | 3.4×108[73][74] | Central galaxy of the Perseus Cluster |

| 3C 390.3 | (2.87±0.64)×108[4] 338840000[5] |

|

| (4.57±0.55)×108[4] 144540000[5] |

||

| (3.69±0.76)×108[4] 218780000[5] |

||

| Messier 59 | 2.7×108[75] | This black hole has a retrograde rotation.[76] |

| (4.43±1.46)×108[4] 79430000[5] |

||

| (2.79±1.29)×108[4] 240000000[5] |

||

| Andromeda Galaxy | 2.3×108 | Nearest large galaxy to the Milky Way |

| (2.76±0.59)×108[4] 182000000[5] |

||

| (3.93±0.96)×108[4] 53700000[5] |

||

| (2.55±0.56)×108[4] 79430000[5] |

||

| NGC 7727 | 1.54+0.18 −0.15×108[77] |

with 6.3×106 companion and the closest confirmed BBH to Earth at about 89 million light years away |

| (1.5±0.19)×108[4] 182000000[5] |

||

| Messier 105 | 1.4×108–2×108[78] | |

| (1.43±0.12)×108[4] 57550000[5] |

||

| OJ 287 secondary | 1×108[30] | The smaller black hole orbiting OJ 287 primary (see above). |

| RX J124236.9-111935 | 1×108[79] | Observed by the Chandra X-ray Observatory to be tidally disrupting a star.[79][80] |

| Messier 85 | 1×108[81] | |

| NGC 5548 | (6.71±0.26)×107[4] 123000000[5] |

|

| (1.46±0.44)×108[4] 40740000[5] |

||

| Messier 88 | 8×107[82] | |

| Messier 81 (Bode's Galaxy) | 7×107[83] | |

| (7.32±3.52)×107[4] 7.586×107[5] |

||

| Messier 58 | 7×107[84] | |

| (9.24±3.81)×107[4] 2.138×107[5] |

||

| Centaurus A | 5.5×107[85] | Also notable for its million light-year long relativistic jet.[86] |

| (5.24±1.44)×107[4] 5.25×107[5] |

||

| Messier 96 | 48000000[87] | Estimates can be as low as 1.5 million solar masses |

| (4.94±0.77)×107[4] 4.365×107[5] |

||

| NGC 3227 | (4.22±2.14)×107[4] 3.89×107[5] |

|

| NGC 4151 primary | 4×107[88][89] | |

| 5.55+3.14 −2.25×107[4] 2.29×107[5] |

||

| (3.49±0.92)×107[4] 4.17×107[5] |

||

| (4.27±1.46)×107[4] 2.3×107[5] |

||

| (4.75±0.74)×107[4] 1.77×107[5] |

||

| Messier 82 (Cigar Galaxy) | 3×107[90] | Prototype starburst galaxy.[91] |

| Messier 108 | 2.4×107[92] | |

| M60-UCD1 | 2×107[93] | Constitutes 15% of the mass of its host galaxy. |

| NGC 3783 | (2.98±0.54)×107[4] 9300000[5] |

|

| (2.51±0.61)×107[4] 5620000[5] |

||

| Markarian 335 | (1.42±0.37)×107[4] 6310000[5] |

|

| NGC 4151 secondary | 10000000[89] | |

| NGC 7469 | (12.2±1.4)×106[4] 6460000[5] |

|

| A | 9.90+17.88 −11.88×106[4] 5010000[5] |

|

| 5.36+9.37 −6.95×106[4] 8130000[5] |

||

| Messier 61 | 5×106[94] | |

| Messier 32 | 1.5×106–5×106[95] | A dwarf satellite galaxy of the Andromeda Galaxy. |

| Sagittarius A* | 4.3×106[96] | The black hole at the center of the Milky Way. |

See also

- List of largest cosmic structures

- List of largest galaxies

- List of least massive black holes

- List of most massive exoplanets

- List of most massive neutron stars

- List of most massive stars

- List of the most distant astronomical objects

- Lists of astronomical objects

References

- ^ a b Merritt, David (2013). Dynamics and Evolution of Galactic Nuclei. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-691-15860-0.

- ^ a b King, Andrew (2003-09-15). "Black Holes, Galaxy Formation, and the MBH-σ Relation". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 596 (1): L27–L29. arXiv:astro-ph/0308342. Bibcode:2003ApJ...596L..27K. doi:10.1086/379143. S2CID 9507887.

- ^ Ferrarese, Laura; Merritt, David (2000-08-10). "A Fundamental Relation between Supermassive Black Holes and Their Host Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. The American Astronomical Society. 539 (1): L9–12. arXiv:astro-ph/0006053. Bibcode:2000ApJ...539L...9F. doi:10.1086/312838. S2CID 6508110.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Peterson, Bradley M. (2013). "Measuring the Masses of Supermassive Black Holes" (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 183 (1–4): 253. Bibcode:2014SSRv..183..253P. doi:10.1007/s11214-013-9987-4. S2CID 16464532.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Nelson, Charles H. (2000). "Black Hole Mass, Velocity Dispersion, and the Radio Source in Active Galactic Nuclei". The Astrophysical Journal. 544 (2): L91–L94. arXiv:astro-ph/0009188. Bibcode:2000ApJ...544L..91N. doi:10.1086/317314. S2CID 117449813.

- ^ September 2020, Paul Sutter 29 (29 September 2020). "Black holes so big we don't know how they form could be hiding in the universe". Space.com. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Shemmer, O.; Netzer, H.; Maiolino, R.; Oliva, E.; Croom, S.; Corbett, E.; di Fabrizio, L. (2004). "Near-infrared spectroscopy of high-redshift active galactic nuclei. I. A metallicity-accretion rate relationship". The Astrophysical Journal. 614 (2): 547–557. arXiv:astro-ph/0406559. Bibcode:2004ApJ...614..547S. doi:10.1086/423607. S2CID 119010341.

- ^ a b c Dullo, B.T. (22 November 2019). "The Most Massive Galaxies with Large Depleted Cores: Structural Parameter Relations and Black Hole Masses". The Astrophysical Journal. 886 (2): 80. arXiv:1910.10240. Bibcode:2019ApJ...886...80D. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab4d4f. S2CID 204838306.

- ^ a b c Dullo, B.T.; de Paz, A.G.; Knapen, J.H. (18 February 2021). "Ultramassive black holes in the most massive galaxies: MBH−σ versus MBH−Rb". The Astrophysical Journal. 908 (2): 134. arXiv:2012.04471. Bibcode:2021ApJ...908..134D. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/abceae. S2CID 227745078.

- ^ Most Powerful Eruption In The Universe Discovered NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (ScienceDaily) January 6, 2005

- ^ McNamara, B. R.; Nulsen, P. E. J.; Wise, M. W.; Rafferty, D. A.; Carilli, C.; Sarazin, C. L.; Blanton, E. L. (2005). "The heating of gas in a galaxy cluster by X-ray cavities and large-scale shock fronts". Nature. 433 (7021): 45–47. Bibcode:2005Natur.433...45M. doi:10.1038/nature03202. PMID 15635404. S2CID 4340763.

- ^ Rafferty, D. A.; McNamara, B. R.; Nulsen, P. E. J.; Wise, M. W. (2006). "The Feedback-regulated Growth of Black Holes and Bulges through Gas Accretion and Starbursts in Cluster Central Dominant Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 652 (1): 216–231. arXiv:astro-ph/0605323. Bibcode:2006ApJ...652..216R. doi:10.1086/507672. S2CID 9481371.

- ^ Mehrgan, K.; Thomas, J.; Saglia, R.; Massalay, X.; Erwin, P.; Bender, R.; Kluge, M.; Fabricius, M. (2019). "A 40-billion solar mass black hole in the extreme core of Holm 15A, the central galaxy of Abell 85". The Astrophysical Journal. 887 (2): 195. arXiv:1907.10608. Bibcode:2019ApJ...887..195M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab5856. S2CID 198899965.

- ^ López-Cruz, O.; Añorve, C.; Birkinshaw, M.; Worrall, D. M.; Ibarra-Medel, H. J.; Barkhouse, W. A.; Torres-Papaqui, J. P.; Motta, V. (2014). "The Brightest Cluster Galaxy in Abell 85: The Largest Core Known So Far". The Astrophysical Journal. 795 (2): L31. arXiv:1405.7758. Bibcode:2014ApJ...795L..31L. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/795/2/L31. S2CID 1140857.

- ^ Dullo, Bililign T.; Graham, Alister W.; Knapen, Johan H. (October 2017). "A remarkably large depleted core in the Abell 2029 BCG IC 1101". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 471 (2): 2321–2333. arXiv:1707.02277. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.471.2321D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx1635. S2CID 119000593.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ghisellini, G.; Ceca, R. Della; Volonteri, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; Tavecchio, F.; Foschini, L.; Tagliaferri, G.; Haardt, F.; Pareschi, G.; Grindlay, J. (2010). "Chasing the heaviest black holes in active galactic nuclei, the largest black hole". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 405 (1): 387. arXiv:0912.0001. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.405..387G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.16449.x. S2CID 40214759.

- ^ Ghisellini, G.; Foschini, L.; Volonteri, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; Haardt, F.; Burlon, D.; Tavecchio, F.; et al. (14 July 2009). "The blazar S5 0014+813: a real or apparent monster?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. v2. 399 (1): L24–L28. arXiv:0906.0575. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.399L..24G. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2009.00716.x. S2CID 14438667.

- ^ Gaensler, Bryan (2012-07-03). Extreme Cosmos: A Guided Tour of the Fastest, Brightest, Hottest, Heaviest, Oldest, and Most Amazing Aspects of Our Universe. ISBN 978-1-101-58701-0.

- ^ Christopher A Onken, Fuyan Bian, Xiaohui Fan, Feige Wang, Christian Wolf, Jinyi Yang (August 2020), "thirty-four billion solar mass black hole in SMSS J2157–3602, the most luminous known quasar", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 496 (2): 2309, arXiv:2005.06868, Bibcode:2020MNRAS.496.2309O, doi:10.1093/mnras/staa1635CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Zuo, Wenwen; Wu, Xue-Bing; Fan, Xiaohui; Green, Richard; Wang, Ran; Bian, Fuyan (2014). "Black Hole Mass Estimates and Rapid Growth of Supermassive Black Holes in Luminous $z \sim$ 3.5 Quasars". The Astrophysical Journal. 799 (2): 189. arXiv:1412.2438. Bibcode:2015ApJ...799..189Z. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/799/2/189. S2CID 73642040.

- ^ a b Walker, S. A.; Fabian, A. C.; Russell, H. R.; Sanders, J. S. (2014). "The effect of the quasar H1821+643 on the surrounding intracluster medium: Revealing the underlying cooling flow". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 442 (3): 2809. arXiv:1405.7522. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.442.2809W. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1067. S2CID 118724526.

- ^ Magorrian, J.; Tremaine, S.; Richstone, D.; Bender, R.; Bower, G.; Dressler, A.; Faber, S.~M.; Gebhardt, K.; Green, R.; Grillmair, C.; Kormendy, J.; Lauer, T. (June 1998). "The Demography of Massive Dark Objects in Galaxy Centers". The Astronomical Journal. 115 (6): 2285–2305. arXiv:astro-ph/9708072. Bibcode:1998AJ....115.2285M. doi:10.1086/300353. S2CID 17256372.

- ^ Jeram, Sarik; Gonzalez, Anthony; Eikenberry, Stephen; Stern, Daniel; Mendes De Oliveira, Claudia Lucia; Izuti Nakazono, Lilianne Mariko; Ackley, Kendall (2020). "An Extremely Bright QSO at z = 2.89". The Astrophysical Journal. 899 (1): 76. arXiv:2006.11915. Bibcode:2020ApJ...899...76J. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab9c95. S2CID 219966890.

- ^ a b Riechers, D. A.; Walter, F.; Carilli, C. L.; Lewis, G. F. (2009). "Imaging The Molecular Gas in a z = 3.9 Quasar Host Galaxy at 0farcs3 Resolution: A Central Sub-Kiloparsec Scale Star Formation Reservoir in APM 08279+5255". The Astrophysical Journal. 690 (1): 463–485. arXiv:0809.0754. Bibcode:2009ApJ...690..463R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/1/463. S2CID 13959993.

- ^ a b Saturni, F. G.; Trevese, D.; Vagnetti, F.; Perna, M.; Dadina, M. (2016). "A multi-epoch spectroscopic study of the BAL quasar APM 08279+5255. II. Emission- and absorption-line variability time lags". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 587: A43. arXiv:1512.03195. Bibcode:2016A&A...587A..43S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527152. S2CID 118548618.

- ^ a b c McConnell, Nicholas J.; Ma, Chung-Pei; Gebhardt, Karl; Wright, Shelley A.; Murphy, Jeremy D.; Lauer, Tod R.; Graham, James R.; Richstone, Douglas O. (2011). "Two ten-billion-solar-mass black holes at the centres of giant elliptical galaxies". Nature. 480 (7376): 215–8. arXiv:1112.1078. Bibcode:2011Natur.480..215M. doi:10.1038/nature10636. PMID 22158244. S2CID 4408896.

- ^ a b c d McConnell, N. J.; Ma, C.-P.; Murphy, J. D.; Gebhardt, K.; Lauer, T. R.; Graham, J. R.; Wright, S. A.; Richstone, D. O. (2012). "Dynamical Measurements of Black Hole Masses in Four Brightest Cluster Galaxies at 100 Mpc". The Astrophysical Journal. 756 (2): 179. arXiv:1203.1620. Bibcode:2012ApJ...756..179M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/756/2/179. S2CID 119114155.

- ^ McDonald, M.; Bayliss, M.; Benson, B. A.; Foley, R. J.; Ruel, J.; Sullivan, P.; Veilleux, S.; Aird, K. A.; Ashby, M. L. N.; Bautz, M.; Bazin, G.; Bleem, L. E.; Brodwin, M.; Carlstrom, J. E.; Chang, C. L.; Cho, H. M.; Clocchiatti, A.; Crawford, T. M.; Crites, A. T.; De Haan, T.; Desai, S.; Dobbs, M. A.; Dudley, J. P.; Egami, E.; Forman, W. R.; Garmire, G. P.; George, E. M.; Gladders, M. D.; Gonzalez, A. H.; et al. (2012). "A massive, cooling-flow-induced starburst in the core of a luminous cluster of galaxies". Nature. 488 (7411): 349–52. arXiv:1208.2962. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..349M. doi:10.1038/nature11379. PMID 22895340. S2CID 205230129.

- ^ "BAT AGN Spectroscopic Survey -- XIII. The nature of the most luminous obscured AGN in the low-redshift universe".

- ^ a b Valtonen, M. J.; Ciprini, S.; Lehto, H. J. (2012). "On the masses of OJ287 black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 427 (1): 77–83. arXiv:1208.0906. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.427...77V. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21861.x. S2CID 118483466.

- ^ Thomas, J.; Ma, C.-P.; McConnell, N. J.; Greene, J. E.; Blakeslee, J. P.; Janish, R. (2016). "A 17-billion-solar-mass black hole in a group galaxy with a diffuse core". Nature. 532 (7599): 340–342. arXiv:1604.01400. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..340T. doi:10.1038/nature17197. PMID 27049949. S2CID 4454301.

- ^ Morrow, Ashley (5 April 2016). "Behemoth Black Hole Found in an Unlikely Place".

- ^ a b Smith, R. J.; Lucey, J. R.; Edge, A. C. (2017). "A counterimage to the gravitational arc in Abell 1201: Evidence for IMF variations or a 1010 Msun black hole?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 467 (1): 836–848. arXiv:1701.02745. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.467..836S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx059. S2CID 59965783.

- ^ Smith, R. J.; Lucey, J. R.; Edge, A. C. (2017). "Stellar dynamics in the strong-lensing central galaxy of Abell 1201: A low stellar mass-to-light ratio a large central compact mass and a standard dark matter halo". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 1706 (1): 383–393. arXiv:1706.07055. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.471..383S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx1573. S2CID 54757451.

- ^ Wu, X.; Wang, F.; Fan, X.; Yi, Weimin; Zuo, Wenwen; Bian, Fuyan; Jiang, Linhua; McGreer, Ian D.; Wang, Ran; Yang, Jinyi; Yang, Qian; Thompson, David; Beletsky, Yuri (25 February 2015). "An ultraluminous quasar with a twelve-billion-solar-mass black hole at redshift 6.30". Nature. 518 (7540): 512–515. arXiv:1502.07418. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..512W. doi:10.1038/nature14241. PMID 25719667. S2CID 4455954.

- ^ "Astronomers Discover Record-Breaking Quasar". Sci-News.com. 2015-02-25. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- ^ Ferré-Mateu, Anna; Mezcua, Mar; Trujillo, Ignacio; Balcells, Marc; Bosch, Remco C. E. van den (2015-07-21). "Massive Relic Galaxies Challenge the Co-Evolution of Super-Massive Black Holes and Their Host Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 808 (1): 79. arXiv:1506.02663. Bibcode:2015ApJ...808...79F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/808/1/79. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 118777377.

- ^ Park, Songyoun; Yang, Jun; Oonk, J. B. Raymond; Paragi, Zsolt (2016-11-22). "Discovery of five low-luminosity active galactic nuclei at the centre of the Perseus cluster". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 465 (4): 3943–3948. arXiv:1611.05986. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.465.3943P. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw3012. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 53538944.

- ^ a b Ghisellini, G.; Tagliaferri, G.; Sbarrato, T.; Gehrels, N. (2015). "SDSS J013127.34-032100.1: A candidate blazar with a 11 billion solar mass black hole at $z$=5.18". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 450: L34–L38. arXiv:1501.07269. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.450L..34G. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slv042. S2CID 118449836.

- ^ a b Liu, Tingting; Gezari, Suvi; Heinis, Sebastien; Magnier, Eugene A.; Burgett, William S.; Chambers, Kenneth; Flewelling, Heather; Huber, Mark; Hodapp, Klaus W.; Kaiser, Nicholas; Kudritzki, Rolf-Peter; Tonry, John L.; Wainscoat, Richard J.; Waters, Christopher (2015). "A Periodically Varying Luminous Quasar at z=2 from the Pan-STARRS1 Medium Deep Survey: A Candidate Supermassive Black Hole Binary in the Gravitational Wave-Driven Regime". The Astrophysical Journal. 803 (2): L16. arXiv:1503.02083. Bibcode:2015ApJ...803L..16L. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/803/2/L16. S2CID 118580031.

- ^ Hlavacek-Larrondo, J.; Allen, S. W.; Taylor, G. B.; Fabian, A. C.; Canning, R. E. Ato.; Werner, N.; Sanders, J. S.; Grimes, C. K.; Ehlert, S.; von Der Linden, A. (2013). "Probing the extreme realm of AGN feedback in the massive galaxy cluster, RX J1532.9+3021". The Astrophysical Journal. 777 (2): 163. arXiv:1306.0907. Bibcode:2013ApJ...777..163H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/777/2/163. S2CID 118597740. Lay summary.

- ^ Yıldırım, Akın; Bosch, Van Den; E, Remco C.; van de Ven, Glenn; Dutton, Aaron; Läsker, Ronald; Husemann, Bernd; Walsh, Jonelle L.; Gebhardt, Karl (2016-02-11). "The massive dark halo of the compact early-type galaxy NGC 1281". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 456 (1): 538–553. arXiv:1511.03131. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.456..538Y. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2665. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 118483580.

- ^ Ferré-Mateu, Anna; Mezcua, Mar; Trujillo, Ignacio; Balcells, Marc; Bosch, Remco C. E. van den (2015-07-21). "Massive Relic Galaxies Challenge the Co-Evolution of Super-Massive Black Holes and Their Host Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 808 (1): 79. arXiv:1506.02663. Bibcode:2015ApJ...808...79F. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/808/1/79. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 118777377.

- ^ Guo, Hengxiao; J. Barth, Aaron (2021). "The Quasar SDSS J140821.67+025733.2 Does Not Contain a 196 Billion Solar Mass Black Hole". American Astronomical Society. 5 (1): 2. Bibcode:2021RNAAS...5....2G. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/abd7f9.

- ^ Trakhtenbrot, Benny; Megan Urry, C.; Civano, Francesca; Rosario, David J.; Elvis, Martin; Schawinski, Kevin; Suh, Hyewon; Bongiorno, Angela; Simmons, Brooke D. (2015). "An Over-Massive Black Hole in a Typical Star-Forming Galaxy, 2 Billion Years After the Big Bang". Science. 349 (168): 168–171. arXiv:1507.02290. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..168T. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4506. PMID 26160942. S2CID 22406584.

- ^ Oldham, L. J.; Auger, M. W. (2016). "Galaxy structure from multiple tracers – II. M87 from parsec to megaparsec scales". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 457 (1): 421–439. arXiv:1601.01323. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.457..421O. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2982. S2CID 119166670.

- ^ Walsh, Jonelle L.; Barth, Aaron J.; Ho, Luis C.; Sarzi, Marc (June 2013). "The M87 Black Hole Mass from Gas-dynamical Models of Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph Observations". The Astrophysical Journal. 770 (2): 86. arXiv:1304.7273. Bibcode:2013ApJ...770...86W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/770/2/86. S2CID 119193955.

- ^ a b Mazzalay, X.; Thomas, J.; Saglia, R. P.; Wegner, G. A.; Bender, R.; Erwin, P.; Fabricius, M. H.; Rusli, S. P. (2016). "The supermassive black hole and double nucleus of the core elliptical NGC 5419". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 462 (3): 2847–2860. arXiv:1607.06466. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.462.2847M. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1802. S2CID 119236364.

- ^ Juntai Shen; Karl Gebhardt (2010). "The Supermassive Black Hole and Dark Matter Halo of NGC 4649 (M60)". The Astrophysical Journal. 711 (1): 484–494. arXiv:0910.4168. Bibcode:2010ApJ...711..484S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/711/1/484. S2CID 119291328.

- ^ a b Dalla Bontà, E.; Ferrarese, L.; Corsini, E. M.; Miralda-Escudé, J.; Coccato, L.; Sarzi, M.; Pizzella, A.; Beifiori, A. (2009). "The High-Mass End of the Black Hole Mass Function: Mass Estimates in Brightest Cluster Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 690 (1): 537–559. arXiv:0809.0766. Bibcode:2009ApJ...690..537D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/1/537. S2CID 17074507.

- ^ Walsh, Jonelle L.; Bosch, Remco C. E. van den; Gebhardt, Karl; Yildirim, Akin; Gültekin, Kayhan; Husemann, Bernd; Richstone, Douglas O. (2015-08-03). "The Black Hole in the Compact, High-Dispersion Galaxy NGC 1271". The Astrophysical Journal. 808 (2): 183. arXiv:1506.05129. Bibcode:2015ApJ...808..183W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/808/2/183. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 41570998.

- ^ Graham, Alister W.; Ciambur, Bogdan C.; Savorgnan, Giulia A. D. (2016). "Disky Elliptical Galaxies and the Allegedly Over-massive Black Hole in the Compact "ES" Galaxy NGC 1271". The Astrophysical Journal. 831 (2): 132. arXiv:1608.00711. Bibcode:2016ApJ...831..132G. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/831/2/132. hdl:1959.3/432781. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 118435675.

- ^ a b Oshlack, A. Y. K. N.; Webster, R. L.; Whiting, M. T. (2002). "Black Hole Mass Estimates of Radio‐selected Quasars". The Astrophysical Journal. 576 (1): 81–88. arXiv:astro-ph/0205171. Bibcode:2002ApJ...576...81O. doi:10.1086/341729. S2CID 15343258.

- ^ Daniel J. Mortlock; Stephen J. Warren; Bram P. Venemans; Patel; Hewett; McMahon; Simpson; Theuns; Gonzáles-Solares; Adamson; Dye; Hambly; Hirst; Irwin; Kuiper; Lawrence; Röttgering; et al. (2011). "A luminous quasar at a redshift of z = 7.085". Nature. 474 (7353): 616–619. arXiv:1106.6088. Bibcode:2011Natur.474..616M. doi:10.1038/nature10159. PMID 21720366. S2CID 2144362.

- ^ John Matson (2011-06-29). "Brilliant, but Distant: Most Far-Flung Known Quasar Offers Glimpse into Early Universe". Scientific American. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ Kormendy, John; Richstone, Douglas (1992). "Evidence for a supermassive black hole in NGC 3115". The Astrophysical Journal. 393: 559–578. Bibcode:1992ApJ...393..559K. doi:10.1086/171528.

- ^ Romani, Roger W. (2006). "The Spectral Energy Distribution of the High-z Blazar Q0906+6930". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (5): 1959–1963. arXiv:astro-ph/0607581. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.1959R. doi:10.1086/508216. S2CID 119331684.

- ^ Bower, G.A.; et al. (1998). "Kinematics of the Nuclear Ionized Gas in the Radio Galaxy M84 (NGC 4374)". Astrophysical Journal. 492 (1): 111–114. arXiv:astro-ph/9710264. Bibcode:1998ApJ...492L.111B. doi:10.1086/311109. S2CID 119456112.

- ^ Jinyi Yang and Feige Wang and Xiaohui Fan and Joseph F. Hennawi and Frederick B. Davies and Minghao Yue and Eduardo Banados and Xue-Bing Wu and Bram Venemans and Aaron J. Barth and Fuyan Bian and Konstantina Boutsia and Roberto Decarli and Emanuele Paolo Farina and Richard Green and Linhua Jiang and Jiang-Tao Li and Chiara Mazzucchelli and Fabian Walter (2020). "Pōniuāʻena: A Luminous z=7.5 Quasar Hosting a 1.5 Billion Solar Mass Black Hole". arXiv:2006.13452. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab9c26. S2CID 220042206. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Graham, Alister W.; Durré, Mark; Savorgnan, Giulia A. D.; Medling, Anne M.; Batcheldor, Dan; Scott, Nicholas; Watson, Beverly; Marconi, Alessandro (1 March 2016). "A Normal Supermassive Black Hole in NGC 1277". The Astrophysical Journal. 819 (1): 43. arXiv:1601.05151. Bibcode:2016ApJ...819...43G. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/819/1/43. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 36974319.

- ^ van den Bosch, Remco C. E.; et al. (29 Nov 2012). "An over-massive black hole in the compact lenticular galaxy NGC 1277". Nature. 491 (7426): 729–731. arXiv:1211.6429. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..729V. doi:10.1038/nature11592. PMID 23192149. S2CID 205231230.

- ^ Emsellem, Eric (Aug 2013). "Is the black hole in NGC 1277 really overmassive?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 433 (3): 1862–1870. arXiv:1305.3630. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.433.1862E. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt840. S2CID 54011632.

- ^ "Black Holes: Gravity's Relentless Pull interactive: Encyclopedia". HubbleSite. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ J. Kormendy; R. Bender; E. A. Ajhar; A. Dressler; S. M. Faber; K. Gebhardt; C. Grillmair; T. R. Lauer; D. Richstone; S. Tremaine (1996). "Hubble Space Telescope Spectroscopic Evidence for a 1 X 10 9 Msun Black Hole in NGC 4594". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 473 (2): L91–L94. Bibcode:1996ApJ...473L..91K. doi:10.1086/310399.

- ^ Rieger, F. M.; Mannheim, K. (2003). "On the central black hole mass in Mkn 501". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 397: 121–126. arXiv:astro-ph/0210326. Bibcode:2003A&A...397..121R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021482. S2CID 14579804.

- ^ a b c Bañados, Eduardo; et al. (6 December 2017). "An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5". Nature. 553 (7689): 473–476. arXiv:1712.01860. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..473B. doi:10.1038/nature25180. PMID 29211709. S2CID 205263326.

- ^ Loewenstein, Michael; et al. (July 2001). "Chandra Limits on X-Ray Emission Associated with the Supermassive Black Holes in Three Giant Elliptical Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 555 (1): L21–L24. arXiv:astro-ph/0106326. Bibcode:2001ApJ...555L..21L. doi:10.1086/323157. S2CID 14873290.

- ^ GEBHARDT, K.; LAUER, T. R.; PINKNEY, J.; BENDER, R.; RICHSTONE, D.; ALLER, M.; BOWER, G.; DRESSLER, A. (December 2007). "The Black Hole Mass and Extreme Orbital Structure in NGC 1399". The Astrophysical Journal. 671 (2): 1321–1328. arXiv:0709.0585. Bibcode:2007ApJ...671.1321G. doi:10.1086/522938. S2CID 12042010.

- ^ "Massive Black Holes Dwell in Most Galaxies, According to Hubble Census". Hubblesite STScI-1997-01. 1997-01-13. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "The Giant Elliptical Galaxy NGC 4261". Astronomy 162 (Dept. Physics & Astronomy University of Tennessee). Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ van, Loon J. T.; Sansom, A. E. (2015). "An evolutionary missing link? A modest-mass early-type galaxy hosting an oversized nuclear black hole". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 453 (3): 2341–2348. arXiv:1508.00698. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.453.2341V. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1787. S2CID 56459588.

- ^ "Black hole is 30 times expected size". phys.org.

- ^ Wilman, R. J.; Edge, A. C.; Johnstone, R. M. (2005). "The nature of the molecular gas system in the core of NGC 1275". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 359 (2): 755–764. arXiv:astro-ph/0502537. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.359..755W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08956.x. S2CID 18190288.

- ^ Wilman, R. J.; Edge, A. C.; Johnstone, R. M. (2005). "The nature of the molecular gas system in the core of NGC 1275". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 359 (2): 755–764. arXiv:astro-ph/0502537. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.359..755W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08956.x. S2CID 18190288.

- ^ Wrobel, J. M.; Terashima, Y.; Ho, L. C. (2008). "Outflow-dominated Emission from the Quiescent Massive Black Holes in NGC 4621 and NGC 4697". The Astrophysical Journal. 675 (2): 1041–1047. arXiv:0712.1308. Bibcode:2008ApJ...675.1041W. doi:10.1086/527542. S2CID 119208491.

- ^ Wernli, F.; Emsellem, E.; Copin, Y. (2002). "A 60 pc counter-rotating core in NGC 4621". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 396: 73–81. arXiv:astro-ph/0209361. Bibcode:2002A&A...396...73W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021333. S2CID 18545003.

- ^ Voggel, K. T.; Seth, A. C.; Baumgardt, H.; Husemann, B.; Neumayer, N.; Hilker, M.; Pechetti, R.; Mieske, S.; Dumont, A.; Georgiev, I. (2021-11-30). "First direct dynamical detection of a dual super-massive black hole system at sub-kpc separation". Astronomy & Astrophysics. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202140827. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Thilker, David A.; Donovan, Jennifer; Schiminovich, David; Bianchi, Luciana; Boissier, Samuel; Gil de Paz; Armando; Madore, Barry F.; Martin, D. Christopher; Seibert, Mark (2009). "Massive star formation within the Leo 'primordial' ring". Nature. 457 (7232): 990–993. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..990T. doi:10.1038/nature07780. PMID 19225520. S2CID 4424307.

- ^ a b Komossa, S.; Halpern, J.; Schartel, N.; Hasinger, G.; Santos-Lleo, M.; Predehl, P. (May 2004). "A Huge Drop in the X-Ray Luminosity of the Nonactive Galaxy RX J1242.6-1119A, and the First Postflare Spectrum: Testing the Tidal Disruption Scenario". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 603 (1): L17–L20. arXiv:astro-ph/0402468. Bibcode:2004ApJ...603L..17K. doi:10.1086/382046. S2CID 53724998.

- ^ NASA: "Giant Black Hole Rips Apart Unlucky Star"

- ^ Kormendy, John; Bender, Ralf (2009). "Correlations between Supermassive Black Holes, Velocity Dispersions, and Mass Deficits in Elliptical Galaxies with Cores". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 691 (2): L142–L146. arXiv:0901.3778. Bibcode:2009ApJ...691L.142K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/691/2/L142. S2CID 18919128.

- ^ Merloni, Andrea; Heinz, Sebastian; di Matteo, Tiziana (2003). "A Fundamental Plane of black hole activity". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 345 (4): 1057–1076. arXiv:astro-ph/0305261. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.345.1057M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2966.2003.07017.x. S2CID 14310323.

- ^ N. Devereux; H. Ford; Z. Tsvetanov & J. Jocoby (2003). "STIS Spectroscopy of the Central 10 Parsecs of M81: Evidence for a Massive Black Hole". Astronomical Journal. 125 (3): 1226–1235. Bibcode:2003AJ....125.1226D. doi:10.1086/367595.

- ^ Merloni, Andrea; Heinz, Sebastian; di Matteo, Tiziana (2003). "A Fundamental Plane of black hole activity". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 345 (4): 1057–1076. arXiv:astro-ph/0305261. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.345.1057M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2966.2003.07017.x. S2CID 14310323.

- ^ "Radio Telescopes Capture Best-Ever Snapshot of Black Hole Jets". NASA. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (2011-04-13). "Centaurus Radio Jets Rising". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ^ Nowak, N.; et al. (April 2010). "Do black hole masses scale with classical bulge luminosities only? The case of the two composite pseudo-bulge galaxies NGC 3368 and NGC 3489". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 403 (2): 646–672. arXiv:0912.2511. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.403..646N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.16167.x. S2CID 59580555.

- ^ "NGC 4151: An active black hole in the "Eye of Sauron"". Astronomy magazine. 2011-03-11. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- ^ a b Bon; Jovanović; Marziani; Shapovalova; Bon; Borka Jovanović; Borka; Sulentic; Popović (2012). "The First Spectroscopically Resolved Sub-parsec Orbit of a Supermassive Binary Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal. 759 (2): 118–125. arXiv:1209.4524. Bibcode:2012ApJ...759..118B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/759/2/118. S2CID 119257514.

- ^ Gaffney, N. I.; Lester, D. F. & Telesco, C. M. (1993). "The stellar velocity dispersion in the nucleus of M82". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 407: L57–L60. Bibcode:1993ApJ...407L..57G. doi:10.1086/186805.

- ^ Barker, S.; de Grijs, R.; Cerviño, M. (2008). "Star cluster versus field star formation in the nucleus of the prototype starburst galaxy M 82". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 484 (3): 711–720. arXiv:0804.1913. Bibcode:2008A&A...484..711B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809653. S2CID 18885080.

- ^ Satyapal, S.; Vega, D.; Dudik, R. P.; Abel, N. P.; Heckman, T.; et al. (2008). "Spitzer Uncovers Active Galactic Nuclei Missed by Optical Surveys in Seven Late-Type Galaxies". Astrophysical Journal. 677 (2): 926–942. arXiv:0801.2759. Bibcode:2008ApJ...677..926S. doi:10.1086/529014. S2CID 16050838.

- ^ Strader, J.; et al. (2013). "The Densest Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal. 775 (1): L6. arXiv:1307.7707. Bibcode:2013ApJ...775L...6S. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/775/1/L6. S2CID 52207639.

- ^ Pastorini, G.; Marconi, A.; Capetti, A.; Axon, D. J.; Alonso-Herrero, A.; Atkinson, J.; Batcheldor, D.; Carollo, C. M.; Collett, J.; Dressel, L.; Hughes, M. A.; Macchetto, D.; Maciejewski, W.; Sparks, W.; van der Marel, R. (2007). "Supermassive black holes in the Sbc spiral galaxies NGC 3310, NGC 4303 and NGC 4258". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 469 (2): 405–423. arXiv:astro-ph/0703149. Bibcode:2007A&A...469..405P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066784. S2CID 849621.

- ^ Valluri, M.; Merritt, D.; Emsellem, E. (2004). "Difficulties with Recovering the Masses of Supermassive Black Holes from Stellar Kinematical Data". Astrophysical Journal. 602 (1): 66–92. arXiv:astro-ph/0210379. Bibcode:2004ApJ...602...66V. doi:10.1086/380896. S2CID 16899097.

- ^ Ghez, A. M.; Salim; Weinberg; Lu; Do; Dunn; Matthews; Morris; Yelda; Becklin; Kremenek; Milosavljevic; Naiman; et al. (2008). "Measuring Distance and Properties of the Milky Way's Central Supermassive Black Hole with Stellar Orbits". Astrophysical Journal. 689 (2): 1044–1062. arXiv:0808.2870. Bibcode:2008ApJ...689.1044G. doi:10.1086/592738. S2CID 18335611.

- Supermassive black holes

- Lists of astronomical objects

- Lists of superlatives in astronomy

- Lists of extreme points