Lynching

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

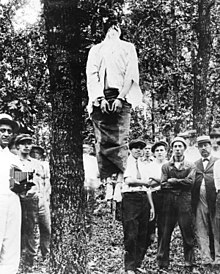

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle (often in the form of hanging) for maximum intimidation.[1] Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in every society.[2][3][4]

In the United States, where the word for "lynching" likely originated, lynchings of African Americans became frequent in the South during the period after the Reconstruction era, especially during the nadir of American race relations.[5]

Etymology[]

The origins of the word lynch are obscure, but it likely originated during the American Revolution. The verb comes from the phrase Lynch Law, a term for a punishment without trial. Two Americans during this era are generally credited for coining the phrase: Charles Lynch (1736–1796) and William Lynch (1742–1820), both of whom lived in Virginia in the 1780s. Charles Lynch is more likely to have coined the phrase, as he was known to have used the term in 1782, while William Lynch is not known to have used the term until much later. There is no evidence that death was imposed as a punishment by either of the two men.[6] In 1782, Charles Lynch wrote that his assistant had administered Lynch's law to Tories "for Dealing with the negroes &c".[7]

Charles Lynch was a Virginia Quaker,[8]:23ff planter, and Patriot who headed a county court in Virginia which imprisoned Loyalists during the war, occasionally imprisoning them for up to a year. Although he lacked proper jurisdiction for detaining these persons, he claimed this right by arguing wartime necessity. Subsequently, Lynch prevailed upon his friends in the Congress of the Confederation to pass a law that exonerated him and his associates from wrongdoing. Lynch was concerned that he might face legal action from one or more of those he had imprisoned, notwithstanding that the Patriots had won the war. This action by the Congress provoked controversy, and it was in connection with this that the term Lynch law, meaning the assumption of extrajudicial authority, came into common parlance in the United States. Lynch was not accused of racist bias. He acquitted Black people accused of murder on three occasions.[9][10] He was accused, however, of ethnic prejudice in his abuse of Welsh miners.[7]

William Lynch from Virginia claimed that the phrase was first used in a 1780 compact signed by him and his neighbors in Pittsylvania County. While Edgar Allan Poe claimed that he found this document, it was probably a hoax.[citation needed]

A 17th-century legend of James Lynch fitz Stephen, who was Mayor of Galway in Ireland in 1493, says that when his son was convicted of murder, the mayor hanged him from his own house.[11] The story was proposed by 1904 as the origin of the word "lynch".[12] It is dismissed by etymologists, both because of the distance in time and place from the alleged event to the word's later emergence, and because the incident did not constitute a lynching in the modern sense.[12][6]

The archaic verb linch, to beat severely with a pliable instrument, to chastise or to maltreat, has been proposed as the etymological source; but there is no evidence that the word has survived into modern times, so this claim is also considered implausible.[8]:16

History[]

Every society has had forms of extrajudicial punishments, including murder. The legal and cultural antecedents of American lynching were carried across the Atlantic by migrants from the British Isles to colonial North America.[13] Collective violence was a familiar aspect of the early American legal landscape, with group violence in colonial America being usually nonlethal in intention and result. In the seventeenth century, in the context of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and unsettled social and political conditions in the American colonies, lynchings became a frequent form of "mob justice" when the authorities were perceived as untrustworthy.[13] In the United States, during the decades after the Civil War, African Americans were the main victims of racial lynching, but in the American Southwest, Mexican Americans were also the targets of lynching as well.[14]

Lynching attacks on African Americans, especially in the South, increased dramatically in the aftermath of Reconstruction, after slavery had been abolished and freed Blacks gained the right to vote. The peak of lynchings occurred in 1892, after White Southern Democrats had regained control of state legislatures. Many incidents were related to economic troubles and competition. At the turn of the 20th century, southern states passed new constitutions or legislation which effectively disenfranchised most Blacks and many Poor Whites, established segregation of public facilities by race, and separated Blacks from common public life and facilities through Jim Crow laws. Nearly 4,800 Americans, including 3,446 African Americans, were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968 in what has been termed by historian as a form of "colonial violence".[15][16]

United States[]

Lynchings took place in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, most commonly in Southern states and Western frontier settlements and most frequently in the late 19th century. They were often performed without due process of law by self-appointed commissions, mobs, or vigilantes as a form of punishment for presumed criminal offences.[17] At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of over 1,000 people.[18]

In the South in the antebellum era, members of the abolitionist movement or other people who opposed slavery were sometimes victims of mob violence. The largest lynching during the war and perhaps the largest lynching in all of U.S. history, was the lynching of 41 men in the Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas in October 1862. Most of the victims were hanged after an extrajudicial "trial" but at least fourteen of them did not receive that formality.[19] The men had been accused of insurrection or treason. Five more men were hanged in Decatur, Texas as part of the same sweep.[20]

After the war, southern Whites struggled to maintain their social dominance. Secret vigilante and insurgent groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings in order to keep Whites in power and discourage freedmen from voting, working and getting educated. They also sometimes attacked Northerners, teachers, and agents of the Freedmen's Bureau. A study of the period from 1868 to 1871[citation needed] estimates that the KKK was involved in more than 400 lynchings. The aftermath of the war was a period of upheaval and social turmoil, in which most White men had been war veterans. Mobs usually alleged crimes for which they lynched Black people. In the late 19th century, however, journalist Ida B. Wells showed that many presumed crimes were either exaggerated or had not even occurred.[21]

From the 1890s onwards, the majority of those lynched were Black,[24] including at least 159 women.[25] Between 1882 and 1968, the Tuskegee Institute recorded 1,297 lynchings of Whites and 3,446 lynchings of Black people.[15][26] However, lynchings of Mexicans were under-counted in the Tuskegee Institute's records,[27] and some of the largest mass lynchings in American history were the Chinese massacre of 1871 and the lynching of eleven Italian immigrants in 1891 in New Orleans.[28]

Mob violence arose as a means of enforcing White supremacy and it frequently verged on systematic political terrorism. "The Ku Klux Klan, paramilitary groups, and other Whites united by frustration and anger ruthlessly defended the interests of White supremacy. The magnitude of the extralegal violence which occurred during election campaigns reached epidemic proportions, leading the historian William Gillette to label it guerrilla warfare."[29][30][31][32][33]

During Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan and others used lynching as a means to control Black people, forcing them to work for planters and preventing them from exercising their right to vote.[29][30][31][32][33] Federal troops and courts enforcing the Civil Rights Act of 1871 largely broke up the Reconstruction-era Klan.

By the end of Reconstruction in 1877, with fraud, intimidation and violence at the polls, White Democrats regained nearly total control of the state legislatures across the South. They passed laws to make voter registration more complicated, reducing Black voters on the rolls. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, from 1890 to 1908, ten of eleven Southern legislatures ratified new constitutions and amendments to effectively disenfranchise most African American people and many poor Whites through devices such as poll taxes, property and residency requirements, and literacy tests. Although required of all voters, some provisions were selectively applied against African Americans. In addition, many states passed grandfather clauses to exempt White illiterates from literacy tests for a limited period. The result was that Black voters were stripped from registration rolls and without political recourse. Since they could not vote, they could not serve on juries. They were without official political voice.

The ideology behind lynching, directly connected with the denial of political and social equality, was stated forthrightly in 1900 by United States Senator Benjamin Tillman, who was previously governor of South Carolina:

We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.[34][35]

Lynchings declined briefly after the takeover[clarification needed] in the 1870s. By the end of the 19th century, with struggles over labor and disenfranchisement, and continuing agricultural depression, lynchings rose again. The number of lynchings peaked at the end of the 19th century, but these kinds of murders continued into the 20th century. Tuskegee Institute records of lynchings between the years 1880 and 1951 show 3,437 African-American victims, as well as 1,293 White victims. Lynchings were concentrated in the Cotton Belt (Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, Texas and Louisiana).[38]

Due to the high rate of lynching, racism, and lack of political and economic opportunities in the South, many Black southerners fled the South to escape these conditions. From 1910 to 1940, 1.5 million southern Black people migrated to urban and industrial Northern cities such as New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Cincinnati, Boston, and Pittsburgh during the Great Migration. The rapid influx of southern Black people into the North changed the ethnic composition of the population in Northern cities, exacerbating hostility between both Black and White Northerners. Many Whites defended their space with violence, intimidation, or legal tactics toward Blacks, while many other Whites migrated to more racially homogeneous regions, a process known as White flight.[39] Overall, Black people in Northern cities experienced systemic discrimination in a plethora of aspects of life.[40] Throughout this period, racial tensions exploded, most violently in Chicago, and lynchings—mob-directed hangings—increased dramatically in the 1920s.[40]

African Americans resisted through protests, marches, lobbying Congress, writing of articles, rebuttals of so-called justifications of lynching, organizing women's groups against lynching, and getting integrated groups against lynching. African-American playwrights produced 14 anti-lynching plays between 1916 and 1935, ten of them by women.

After the release of the movie The Birth of a Nation (1915), which glorified lynching and the Reconstruction-era Klan, the Klan re-formed. Unlike its earlier form, it was heavily represented among urban populations, especially in the Midwest. In response to a large number of mainly Catholic and Jewish immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, the Klan espoused an anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish stance, in addition to exercising the oppression of Black people.

Members of mobs that participated in lynchings often took photographs of what they had done to their victims in order to spread awareness and fear of their power. Souvenir taking, such as pieces of rope, clothing, branches and sometimes body parts was not uncommon. Some of those photographs were published and sold as postcards. In 2000, James Allen published a collection of 145 lynching photos in book form as well as online,[41] with written words and video to accompany the images.

Dyer Bill[]

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was first introduced to the United States Congress in 1918 by Republican Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis, Missouri. The bill was passed by the United States House of Representatives in 1922, and in the same year it was given a favorable report by the United States Senate Committee. Its passage was blocked by White Democratic senators from the Solid South, the only representatives elected since the southern states had disenfranchised African Americans around the start of the 20th century.[43] The Dyer Bill influenced later anti-lynching legislation, including the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which was also defeated in the US Senate.[44]

As passed by the House, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill stated:

"To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching.... Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the phrase 'mob or riotous assemblage,' when used in this act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more persons acting in concert for the purpose of depriving any person of his life without authority of law as a punishment for or to prevent the commission of some actual or supposed public offense."[45]

Decline and Civil Rights Movement[]

While the frequency of lynching dropped in the 1930s, there was a spike in 1930 during the Great Depression. For example, in North Texas and southern Oklahoma alone, four people were lynched in separate incidents in less than a month. In his book Russia Today: What Can We Learn from It? (1934), Sherwood Eddy wrote: "In the most remote villages of Russia today Americans are frequently asked what they are going to do to the Scottsboro Negro boys and why they lynch Negroes."[46] A spike in lynchings occurred after World War II, as tensions arose after veterans returned home. Whites tried to re-impose White supremacy over returning Black veterans. The last documented mass lynching occurred in Walton County, Georgia, in 1946, when two war veterans and their wives were killed by local White landowners.

By the 1950s, the Civil rights movement was gaining new momentum. It was spurred by the lynching of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old youth from Chicago who was killed while visiting an uncle in Mississippi. His mother insisted on having an open-casket funeral so that people could see how badly her son had been beaten. The Black community throughout the U.S. became mobilized.[47] Vann R. Newkirk wrote "the trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of white supremacy".[47] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were acquitted by an all-White jury.[48]

David Jackson writes that it was the photograph of the "child’s ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism."[49] Soviet media frequently covered racial discrimination in the U.S.[50] Deeming American criticism of Soviet Union human rights abuses at this time as hypocrisy, the Russians responded with "And you are lynching Negroes".[51] In Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (2001), the historian Mary L. Dudziak wrote that Soviet Communist criticism of racial discrimination and violence in the United States influenced the federal government to support civil rights legislation.[52]

Most, but not all, lynchings ceased by the 1960s.[15][26] The murder of James Craig Anderson in Mississippi in 2011 was the last recorded fatal lynching in the United States.

Civil rights law[]

Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241, is the civil rights conspiracy statute, which makes it unlawful for two or more persons to conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person of any state, territory, or district in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him/her by the Constitution or the laws of the United States (or because of his/her having exercised the same) and further makes it unlawful for two or more persons to go in disguise on the highway or premises of another person with intent to prevent or hinder their free exercise or enjoyment of such rights. Depending upon the circumstances of the crime, and any resulting injury, the offense is punishable by a range of fines and/or imprisonment for any term of years up to life, or the death penalty.[53]

Felony lynching[]

The term "felony lynching" was formerly used in California law to describe the act of taking someone out of the custody of a police officer by "means of riot". The California law did not specify that the person taken out of custody would be murdered, and in some cases this statute was used to charge individuals who tried to free a person from police custody. There have been several notable cases in the twenty-first century, some controversial, when a Black person has attempted to free another Black person from police custody.[54][55] In 2015, Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation introduced by Senator Holly Mitchell removing the word "lynching" from the state's criminal code, after it received unanimous approval in a vote by state lawmakers. Mitchell stated, "It's been said that strong words should be reserved for strong concepts, and 'lynching' has such a painful history for African Americans that the law should only use it for what it is – murder by mob." The law was otherwise unchanged.[56]

Effects[]

A 2017 study found that exposure to lynchings in the post-Reconstruction South "reduced local black voter turnout by roughly 2.5 percentage points."[57] There was other violence directed at Blacks, particularly in campaign season. Most significantly for voting, from 1890 to 1908, southern states passed new constitutions and laws that disenfranchised most Blacks due to barriers to voter registration. These actions had major effects, soon reducing Black voter turnout in most of the South to insignificant amounts.

Another 2017 study found supportive evidence of Stewart Tolnay and E. M. Beck's claim that lynchings were "due to economic competition between African American and white cotton workers".[58] The study found that lynchings were associated with greater Black out-migration from 1920 to 1930, and higher state-level wages.[58]

After the lynching of Leo Frank, around half of Georgia's 3,000 Jews left the state.[59] According to author Steve Oney, "What it did to Southern Jews can't be discounted ... It drove them into a state of denial about their Judaism. They became even more assimilated, anti-Israel, Episcopalian. The Temple did away with chupahs at weddings – anything that would draw attention."[60]

In 2018, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice was opened in Montgomery, Alabama, a memorial that commemorates the victims of lynchings in the United States.

Europe[]

In Liverpool, a series of race riots broke out in 1919 after the end of the First World War between White and Black sailors, many of whom were demobilized. After a Black sailor had been stabbed by two White sailors in a pub for refusing to give them a cigarette, his friends attacked them the next day in revenge, wounding a policeman in the process. The police responded by launching raids on lodging houses in primarily Black neighborhoods, with casualties on both sides. A White lynch mob gathered outside the houses during the raids and chased a Black sailor, Charles Wootton into the Mersey River where he drowned.[61] The Charles Wootton College in Liverpool has been named in his memory.[62]

In 1944, Wolfgang Rosterg, a German prisoner of war known to be unsympathetic to the Nazi regime, was lynched by other German prisoners of war in Cultybraggan Camp, a prisoner-of-war camp in Comrie, Scotland. At the end of the Second World War, five of the perpetrators were hanged at Pentonville Prison – the largest multiple execution in 20th-century Britain.[63][better source needed]

The situation is less clear with regards to reported "lynchings" in Germany. Nazi propaganda sometimes tried to depict state-sponsored violence as spontaneous lynchings. The most notorious instance of this was "Kristallnacht", which the government portrayed as the result of "popular wrath" against Jews, but it was carried out in an organised and planned manner, mainly by SS men. Similarly, the approximately 150 confirmed murders of surviving crew members of crashed Allied aircraft in revenge for what Nazi propaganda called "Anglo-American bombing terror" were chiefly conducted by German officials and members of the police or the Gestapo, although civilians sometimes took part in them. The execution of enemy aircrew without trial in some cases had been ordered by Hitler personally in May 1944. Publicly it was announced that enemy pilots would no longer be protected from "public wrath". There were secret orders issued that prohibited policemen and soldiers from interfering in favor of the enemy in conflicts between civilians and Allied forces, or prosecuting civilians who engaged in such acts.[64][65] In summary,

- "the assaults on crashed allied aviators were not typically acts of revenge for the bombing raids which immediately preceded them. [...] The perpetrators of these assaults were usually National Socialist officials, who did not hesitate to get their own hands dirty. The lynching murder in the sense of self-mobilizing communities or urban quarters was the exception."[66]

Lynching of members of the Turkish Armed Forces occurred in the aftermath of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt.[67]

Latin America[]

Mexico[]

Lynchings are a persistent form of extralegal violence in post-Revolutionary Mexico.[68]

On September 14, 1968, five employees from the Autonomous University of Puebla were lynched in the village of San Miguel Canoa, in the state of Puebla, after Enrique Meza Pérez, the local priest, incited the villagers to murder the employees, who he believed were communists. The five victims intended to enjoy their holiday climbing La Malinche, a nearby mountain, but they had to stay in the village due to adverse weather conditions. Two of the employees, and the owner of the house where they were staying for the night, were killed; the three survivors sustained serious injuries, including finger amputations.[69] The alleged main instigators were not prosecuted. The few arrested were released after no evidence was found against them.[70]

On November 23, 2004, in the Tlahuac lynching,[71] three Mexican undercover federal agents investigating a narcotics-related crime were lynched in the town of San Juan Ixtayopan (Mexico City) by an angry crowd who saw them taking photographs and suspected that they were trying to abduct children from a primary school. The agents immediately identified themselves but they were held and beaten for several hours before two of them were killed and set on fire. The incident was covered by the media almost from the beginning, including their pleas for help and their murder.

By the time police rescue units arrived, two of the agents were reduced to charred corpses and the third was seriously injured. Authorities suspect that the lynching was provoked by the persons who were being investigated. Both local and federal authorities had abandoned the agents, saying that the town was too far away for them to try to intervene. Some officials said they would provoke a massacre if the authorities tried to rescue the men from the mob.

Brazil[]

According to The Wall Street Journal, "Over the past 60 years, as many as 1.5 million Brazilians have taken part in lynchings...In Brazil, mobs now kill—or try to kill—more than one suspected lawbreaker a day, according to University of São Paulo sociologist José de Souza Martins, Brazil’s leading expert on lynchings."[72]

Bolivia[]

On July 21, 1946, a rioting mob of striking students, teachers, and miners in the Bolivian capital of La Paz lynched various government officials including President Gualberto Villarroel himself. After storming the government palace, members of the mob shot the president and threw his body out of a window. In the Plaza Murillo outside the government palace, Villarroel's body was lynched, his clothes torn, and his almost naked corpse hung on a lamp post. Other victims of the lynching included Director General of Transit Max Toledo, Captain Waldo Ballivián, Luis Uría de la Oliva, the president's secretary, and the journalist Roberto Hinojosa.[73]

Guatemala[]

In May 2015, a sixteen-year-old girl was lynched in Rio Bravo by a vigilante mob after being accused of involvement in the killing of a taxi driver earlier in the month.[74]

Dominican Republic[]

Extrajudicial punishment, including lynching, of alleged criminals who committed various crimes, ranging from theft to murder, has some endorsement in Dominican society. According to a 2014 Latinobarómetro survey, the Dominican Republic had the highest rate of acceptance in Latin America of such unlawful measures.[75] These issues are particularly evident in the Northern Region.[76]

Haiti[]

After the 2010 earthquake the slow distribution of relief supplies and the large number of affected people created concerns about civil unrest, marked by looting and mob justice against suspected looters.[77][78][79][80][81] In a 2010 news story, CNN reported, "At least 45 people, most of them Vodou priests, have been lynched in Haiti since the beginning of the cholera epidemic by angry mobs blaming them for the spread of the disease, officials said.[82]

South Africa[]

The practice of whipping and necklacing offenders and political opponents evolved in the 1980s during the apartheid era in South Africa. Residents of Black townships formed "people's courts" and used whip lashings and deaths by necklacing in order to terrorize fellow Blacks who were seen as collaborators with the government. Necklacing is the torture and execution of a victim by igniting a kerosene-filled rubber tire that has been forced around the victim's chest and arms. Necklacing was used to punish victims who were alleged to be traitors to the Black liberation movement along with their relatives and associates. Sometimes the "people's courts" made mistakes, or they used the system to punish those whom the anti-Apartheid movement's leaders opposed.[83] A tremendous controversy arose when the practice was endorsed by Winnie Mandela, then the wife of the then-imprisoned Nelson Mandela and a senior member of the African National Congress.[84]

More recently, drug dealers and other gang members have been lynched by People Against Gangsterism and Drugs, a vigilante organization.

Nigeria[]

The practice of extrajudicial punishments, including lynching, is referred to as 'jungle justice' in Nigeria.[85] The practice is widespread and "an established part of Nigerian society", predating the existence of the police.[85] Exacted punishments vary between a "muddy treatment", that is, being made to roll in the mud for hours[86] and severe beatings followed by necklacing.[87] The case of the Aluu four sparked national outrage. The absence of a functioning judicial system and law enforcement, coupled with corruption are blamed for the continuing existence of the practice.[88][89]

Palestine and Israel[]

Palestinian lynch mobs have murdered Palestinians suspected of collaborating with Israel.[90][91][92] According to a Human Rights Watch report from 2001:

During the First Intifada, before the PA was established, hundreds of alleged collaborators were lynched, tortured or killed, at times with the implied support of the PLO. Street killings of alleged collaborators continue into the current intifada ... but at much fewer numbers.[93]

On October 12, 2000, the Ramallah lynching took place. This happened at the el-Bireh police station, where a Palestinian crowd killed and mutilated the bodies of two Israel Defense Forces reservists, Vadim Norzhich (Nurzhitz) and Yosef "Yossi" Avrahami,[a] who had accidentally[94] entered the Palestinian Authority-controlled city of Ramallah in the West Bank and were taken into custody by Palestinian Authority policemen. The Israeli reservists were beaten and stabbed. At this point, a Palestinian (later identified as Aziz Salha), appeared at the window, displaying his blood-soaked hands to the crowd, which erupted into cheers. The crowd clapped and cheered as one of the soldier's bodies was then thrown out the window and stamped and beaten by the frenzied crowd. One of the two was shot, set on fire, and his head beaten to a pulp.[95] Soon after, the crowd dragged the two mutilated bodies to Al-Manara Square in the city center and began an impromptu victory celebration.[96][97][98][99] Police officers proceeded to try and confiscate footage from reporters.[96]

In July 2014, three Israeli men kidnapped Mohammed Abu Khdeir, a 16-year-old Palestinian, while he was waiting for dawn Ramadan prayers outside of his house in Eastern Jerusalem. They forced him into their car and beat him while driving to the deserted forest area near Jerusalem, then poured gasoline on him and set him on fire after he was tortured and beaten many times.[100] On November 30, 2015, the two minors involved were found guilty of Khdeirs' murder, and were respectively sentenced to life and 21 years imprisonment on February 4. On May 3, 2016, Ben David was sentenced to life in prison and an additional 20 years.[101]

On October 18, 2015, an Eritrean asylum seeker, Haftom Zarhum, was lynched by a mob of vengeful Israeli soldiers in Be'er Sheva's central bus station. Israeli security forces misidentified Haftom as the person who shot Israeli police bus and shot him. Moments after, other security forces joined shooting Haftom when he was bleeding on the ground. Then, a soldier hit him with a bench nearby when two other soldiers approached the victim then forcefully kicked his head and upper body. Another soldier threw a bench over him to prevent his movement. At that moment a bystander pushed the bench away but the security forces put back the chair and kicked the victim again and pushed the stopper away. Israeli medical forces did not evacuate the victim until eighteen minutes after the first shooting although the victim received 8 shots.[102] In January 2016 four security forces were charged in connection with the lynching.[103] The Israeli civilian who was involved in lynching the Eritrean civilian was sentenced to 100 days community service and 2,000 shekels.[104]

In August 2012, seven Israeli youths were arrested in Jerusalem for what several witnesses described as an attempted lynching of several Palestinian teenagers. The Palestinians received medical treatment and judicial support from Israeli facilities.[105]

Afghanistan[]

On March 19, 2015 in Kabul, Afghanistan a large crowd beat a young woman, Farkhunda, after she was accused by a local mullah of burning a copy of the Quran, Islam's holy book. Shortly afterwards, a crowd attacked her and beat her to death. They set the young woman's body on fire on the shore of the Kabul River. Although it was unclear whether the woman had burned the Quran, police officials and the clerics in the city defended the lynching, saying that the crowd had a right to defend their faith at all costs. They warned the government against taking action against those who had participated in the lynching.[106] The event was filmed and shared on social media.[107] The day after the incident six men were arrested on accusations of lynching, and Afghanistan's government promised to continue the investigation.[108] On March 22, 2015, Farkhunda's burial was attended by a large crowd of Kabul residents; many demanded that she receive justice. A group of Afghan women carried her coffin, chanted slogans and demanded justice.[109]

India[]

In India, lynchings may reflect internal tensions between ethnic communities. Communities sometimes lynch individuals who are accused or suspected of committing crimes. An example is the 2006 Kherlanji massacre, where four members of a Dalit family were slaughtered by Kunbi caste members in Khairlanji, a village in the Bhandara district of Maharashtra. Though this incident was reported as an example of "upper" caste violence against members of a "lower" caste, it was found to be an example of communal violence. It was retaliation against a family who had opposed the Eminent Domain seizure of its fields so a road could be built that would have benefitted the group who murdered them.[110] The women of the family were paraded naked in public, before being mutilated and murdered. Sociologists and social scientists reject attributing racial discrimination to the caste system and attributed this and similar events to intra-racial ethno-cultural conflicts.[111][112]

There have been numerous lynchings in relation to cow vigilante violence in India since 2014,[113] mainly involving Hindu mobs lynching Indian Muslims[114][115] and Dalits.[116][117] Some notable examples of such attacks include the 2015 Dadri mob lynching,[118] the 2016 Jharkhand mob lynching,[119][120][121] 2017 Alwar mob lynching.[122][123] and the 2019 Jharkhand mob lynching. Mob lynching was reported for the third time in Alwar in July 2018, when a group of cow vigilantes killed a 31 year old Muslim man named Rakbar Khan.[124]

In the 2015 Dimapur mob lynching, a mob in Dimapur, Nagaland, broke into a jail and lynched an accused rapist on March 5, 2015 while he was awaiting trial.[125]

Since May 2017, when seven people were lynched in Jharkhand, India has experienced another spate of mob-related violence and killings known as the Indian WhatsApp lynchings following the spread of fake news, primarily relating to child-abduction and organ harvesting, via the Whatsapp message service.[126]

In 2018 Junior civil aviation minister of India had garlanded and honoured eight men who had been convicted in the lynching of trader Alimuddin Ansari in Ramgarh in June 2017 in a case of alleged cow vigilantism.[127]

In June 2019, the Jharkhand mob lynching triggered widespread protests. The victim was a Muslim man and was allegedly forced to chant Hindu slogans, including "Jai Shri Ram".[128][129]

In July 2019, three men were beaten to death and lynched by mobs in Chhapra district of Bihar, on a minor case of theft of cattle.[130]

Four civilians have been lynched by villagers in Jharkhand on witchcraft suspicion, after panchayat decided that they are practicing black magic.[131]

In popular culture[]

"Strange Fruit"[]

"Strange Fruit", a 1937 song composed by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from New York inspired by the photograph of a lynching in Marion, Indiana. Meeropol said that the photograph "haunted me for days".[132] It was published as a poem in the New York Teacher and later in the magazine New Masses, in both cases under the pseudonym Lewis Allan. The poem was set to music, also by Meeropol, and the song was performed and popularized by Billie Holiday.[133] The song reached 16th place on the charts in July 1939.[citation needed] The song has been performed by many other singers, including Nina Simone.

The Hateful Eight[]

The 2015 film The Hateful Eight, set in post Civil War America, depicts a detailed and closely focused lynching of a White woman in the finale, prompting some debate about whether it is a political commentary on racism and hate in America or if it was simply created for entertainment value.[134][135]

Michiel de Ruyter[]

Michiel de Ruyter, English version Admiral. A Dutch biographical film depicting the 1672 assassination of Dutch politicians Johan de Witt and Cornelis de Witt by a carefully organised lynch mob in the Netherlands. [136][137]

See also[]

- Frontier justice

- Hate crime

- Lynching of Jesse Washington

- John J. Hoover lynching

- Kneecapping

- List of lynching victims in the United States

- Mary Turner

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Mobbing

- Noose

- Opera House Lynching

- Pogrom

- Posse

- Struggle session

- Summary execution

- Tarring and feathering

- Vigilantism

- Warning out of town

- Whitecapping

- Witch hunt

- Honor killing

Notes[]

- ^ Wood, Amy Louise (2009). Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874–1947. North Carolina University Press. ISBN 9780807878118. OCLC 701719807.

- ^ Berg, Manfred; Wendt, Simon (2011). Globalizing Lynching History: Vigilantism and Extralegal Punishment from an International Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-11588-0.

- ^ Huggins, Martha Knisely (1991). Vigilantism and the state in modern Latin America : essays on extralegal violence. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0275934764. OCLC 22984858.

- ^ Thurston, Robert W. (2011). Lynching : American mob murder in global perspective. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 9781409409083. OCLC 657223792.

- ^ Hill, Karlos K. (February 28, 2016). "21st Century Lynchings?". Cambridge Blog. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Michael Quinion (December 20, 2008). "Lynch". World Wide Words. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Waldrep, Christopher (2006). "Lynching and Mob Violence". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American History 1619–1895. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780195167771.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cutler, James Elbert (1905). Lynch-law: An Investigation Into the History of Lynching in the United States. Longmans Green and Co.

- ^ "The Atlantic Monthly Volume 0088 Issue 530 (Dec 1901)". Digital.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ University of Chicago, Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary (1913 + 1828) Archived May 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mitchell, James (1966–1971). "Mayor Lynch of Galway: A Review of the Tradition". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. 32: 5–72. JSTOR 25535428.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matthews, Albert (October 1904). "The Term Lynch Law". Modern Philology. 2 (2): 173–195 : 183–184. doi:10.1086/386635. JSTOR 432538. S2CID 159492304.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pfeifer, Michael J. (2011). The Roots of Rough Justice : Origins of American Lynching. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252093098. OCLC 724308353.

- ^ Carrigan, William D.; Clive Webb (2013). Forgotten Dead : Mob Violence against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195320350. OCLC 815043342.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Lynchings: By State and Race, 1882–1968". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on June 29, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

- ^ Smith, Thomas E. (Fall 2007). "The Discourse of Violence: Transatlantic Narratives of Lynching during High Imperialism". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. Johns Hopkins University Press. 8 (2). doi:10.1353/cch.2007.0040. S2CID 162330208.

- ^ The Guardian, 'Jim Crow lynchings more widespread than previously thought', Lauren Gambino, February 10, 2015

- ^ William Hyde and Howard L. Conrad (eds.), Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis: A Compendium of History and Biography for Ready Reference: Volume 4. New York: Southern History Company, 1899; pg. 1913.

- ^ McCaslin, Richard B. Tainted Breeze: The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas 1862, Louisiana State University Press, 1994, p. 81

- ^ McCaslin, p. 95

- ^ "Lynching". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on October 28, 2009.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff George H. Loney". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Shaped by Site: Three Communities' Dialogues on the Legacies of Lynching Archived December 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." National Park Service. Accessed October 29, 2008.

- ^ Robert A. Gibson. "The Negro Holocaust: Lynching and Race Riots in the United States, 1880–1950". Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ DeLongoria, Maria (December 2006). "Stranger Fruit": The Lynching of Black Women the Cases of Rosa Richardson and Marie Scott (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Missouri–Columbia. pp. 1, 77, 142. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lynchings: By Year and Race". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

- ^ Carrigan, William D. (Winter 2003). "The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928". Journal of Social History. 37 (2): 411–438. doi:10.1353/jsh.2003.0169. S2CID 143851795.

For instance, the files at Tuskegee Institute contain the most comprehensive count of lynching victims in the United States, but they only refer to the lynching of fifty Mexicans in the states of Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas. Our own research has revealed a total of 216 victims during the same time period.

- ^ "When Italian immigrants were 'the other'". CNN. July 10, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brundage, W. Fitzhugh (1993). Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06345-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crouch, Barry A. (1984). "A Spirit of Lawlessness: White violence, Texas Blacks, 1865–1868". Journal of Social History. 18 (2): 217–226. doi:10.1353/jsh/18.2.217. JSTOR 3787285.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 119–123. ISBN 0-06-015851-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stagg, J. C. A. (1974). "The Problem of Klan Violence: The South Carolina Upcountry, 1868–1871". Journal of American Studies. 8 (3): 303–318. doi:10.1017/S0021875800015905.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trelease, Allen W. (1979). White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-313-21168-X.

- ^ Herbert, Bob (January 22, 2008). "The Blight That Is Still With Us". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ "'Their Own Hotheadedness': Senator Benjamin R. 'Pitchfork Ben' Tillman Justifies Violence Against Southern Blacks". History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web. George Mason University. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Black Woman Reformer: Ida B. Wells, Lynching, & Transatlantic Activism. University of Georgia Press. 2015. p. 1.

- ^ Moyers, Bill. "Legacy of Lynching". PBS. Retrieved July 28, 2016

- ^ Glanton, Dahleen (May 5, 2002). "South revisits ghastly part of past". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019.

- ^ Seligman, Amanda (2005). Block by block : neighborhoods and public policy on Chicago's West Side. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 213–14. ISBN 978-0-226-74663-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Michael O. Emerson, Christian Smith (2001). "Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America". p. 42. Oxford University Press

- ^ Allen, James. "Musarium: Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America". Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ "The lynching of Leo Frank". leofranklynchers.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000. Accessed March 10, 2008.

- ^ Zangrando, NAACP Crusade, pp. 43–44, 54.

- ^ ""Anti-Lynching Bill," 1918". Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600–2000. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Eddy, Sherwood (1934), Russia Today: What Can We Learn from It?, New York: Farrar & Rinehar, pp. 73, 151, OCLC 1617454

- ^ Jump up to: a b II, Vann R. Newkirk. "How 'The Blood of Emmett Till' Still Stains America Today". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Whitfield, Stephen (1991). A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till. pp 41–42. JHU Press.

- ^ "How The Horrific Photograph Of Emmett Till Helped Energize The Civil Rights Movement". 100photos.time.com. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Quinn, Allison (November 27, 2014), "Soviet Propaganda Back in Play With Ferguson Coverage", The Moscow Times, retrieved December 17, 2016

- ^ Volodzko, David (May 12, 2015), "The History Behind China's Response to the Baltimore Riots", The Diplomat, archived from the original on April 28, 2016, retrieved December 17, 2016,

Soon Americans who criticized the Soviet Union for its human rights violations were answered with the famous tu quoque argument: 'A u vas negrov linchuyut' (and you are lynching Negroes).

- ^ Dudziak, M.L.: Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (2001)

- ^ "Miami". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007.

- ^ Barragan, James (September 4, 2014). "Murrieta immigration protesters charged with obstructing officers". Latimes.com. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Kenney, Tanasia (June 3, 2016). "Pasadena Black Lives Matter Activist Convicted of 'Felony Lynching', Could Spend Four Years Behind Bars". Atlantablackstar.com. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "California legislation removing "lynching" from law signed by Governor Jerry Brown". CBSNews.com. July 3, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Daniel B.; Troesken, Werner; Walsh, Randall (August 4, 2017). "Political participation in a violent society: The impact of lynching on voter turnout in the post-Reconstruction South". Journal of Development Economics. 129: 29–46. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.08.001.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christian, Cornelius (2017). "Lynchings, Labour, and Cotton in the US South: A Reappraisal of Tolnay and Beck". Explorations in Economic History. 66: 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2017.08.005.

- ^ Theoharis and Cox p. 45.

- ^ Yarrow, Allison (May 13, 2009). "The People Revisit Leo Frank". Forward.

- ^ "The roots of racism in city of many cultures". Liverpool Echo. August 3, 2005. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Jacqueline Nassy (2005). Dropping Anchor, Setting Sail: Geographies of Race in Black Liverpool. Princeton University Press, pp. 21, 23, 144.

- ^ "Execution at Camp 21". Caledonia.tv. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007.

- ^ "Hamm 1944". polizeihistorischesammlung-paul.de.

- ^ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg (November 19, 2001). "KRIEGSVERBRECHEN: Systematischer Mord - DER SPIEGEL 47/2001". Spiegel Online. 47. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Grimm, Barbara: "Lynchmorde an alliierten Fliegern im Zweiten Weltkrieg". In: Dietmar Süß (Hrsg.): Deutschland im Luftkrieg. Geschichte und Erinnerung. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-486-58084-1, pp. 71–84. p. 83. "Die Übergriffe auf abgestürzte alliierte Flieger waren im Regelfall keine Racheakte für unmittelbar vorangegangene Bombenangriffe. [...] Täter waren in der Regel nationalsozialistische Funktionsträger, die keine Scheu davor hatten, selbst Hand anzulegen. Der Lynchmord im Sinne sich selbstmobilisierender Kommunen und Stadtviertel war dagegen die Ausnahme."

- ^ "Europe's Flashpoints". Close Up — The Current Affairs Documentary. Episode 2. 2018. Event occurs at 2:12. Deutsche Welle TV. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018.

Public anger erupted. Soldiers were lynched in the streets including young recruits proven to have been deceived by their generals about the true intentions of the attack.

Alt URL - ^ Kloppe-Santamaría, Gema (2020). In the vortex of violence: lynching, extralegal justice, and the state in post-revolutionary Mexico. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-97532-3. OCLC 1145910776.

- ^ Pierre, Beaucage (June 1, 2010). "Representaciones y conductas. Un repertorio de las violencias entre los nahuas de la Sierra Norte de Puebla". Trace. Travaux et recherches dans les Amériques du Centre (in Spanish) (57). ISSN 0185-6286. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Daniel Hernández. "A 45 años del linchamiento en Canoa, nunca se hizo justicia" (in Spanish).

- ^ Niels A. Uildriks (2009), Policing Insecurity: Police Reform, Security, and Human Rights in Latin America Policing Insecurity: Police Reform, Security, and Human Rights in Latin America]. Rowman & Littlefield, p. 201.

- ^ "In Latin America, Awash in Crime, Citizens Impose Their Own Brutal Justice". The Wall Street Journal. December 6, 2018.

- ^ capuchainformativa_ecmn0t (July 22, 2020). "Bolivia │ Así cayó Villarroel: Miradas de la revuelta del 21 de julio de 1946". Capucha Informativa (in Spanish). Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ Annie Rose Ramos; Catherine E. Shoichet; Richard Beltran. "Video of mob burning teen in Guatemala spurs outrage". Cnn.com. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Amnesty International | Working to Protect Human Rights Archived August 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Santana, Antonio (June 9, 2012). "Linchamientos en el norte de la República Dominicana alarman a las autoridades". Lainformacion.com (in Spanish). Santiago. EFE. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ "Mob justice in Haiti". thestar.com. January 17, 2010.

- ^ Romero, Simon; Lacey, Marc (January 17, 2010). "Looting Flares Where Authority Breaks Down". Nytimes.com. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Login". Timesonline.co.uk.

- ^ Rory Carroll (January 16, 2010). "Looters roam Port-au-Prince as earthquake death toll estimate climbs". The Guardian.

- ^ Sherwell, Philip; Colin Freeman (January 16, 2010). "Haiti earthquake: UN says worst disaster ever dealt with". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Valme, Jean M. (December 24, 2010). "Officials: 45 people lynched in Haiti amid cholera fears". CNN. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ "4. Background: The Black Struggle For Political Power: Major Forces in the Conflict". The Killings in South Africa: The Role of the Security Forces and the Response of the State. Human Rights Watch. January 8, 1991. ISBN 0-929692-76-4. Retrieved November 6, 2006.

- ^ Beresford, David (January 27, 1989). "Row over 'mother of the nation' Winnie Mandela". The Guardian. Guardian Newspapers Limited. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BBC NEWS - World - Africa - Nigeria's vigilante 'jungle justice'". News.bbc.co.uk. April 28, 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Dachen, Isaac (October 25, 2016). "Jungle Justice: Cable thief given muddy treatment in Anambra (Graphic Photos)". Pulse.ng. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Burning 7-year-old boy to death an embarrassment to Nigeria - Annie Idibia, Mercy Johnson". Dailypost.ng. November 18, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Jungle Justice: A Vicious Violation Of Human Rights In Africa". Answersafrica.com. July 24, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Luke, Nneka (July 26, 2016). "When the mob rules: jungle justice in Africa". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Be'er, Yizhar & 'Abdel-Jawad, Saleh (January 1994), "Collaborators in the Occupied Territories: Human Rights Abuses and Violations" Archived July 15, 2004, at the Wayback Machine (Microsoft Word document), B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories. Retrieved September 14, 2009. Also .

- ^ Huggler, Justin & Ghazali, Sa'id (October 24, 2003), "Palestinian collaborators executed", The Independent, reproduced on fromoccupiedpalestine.org. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne (March 15, 2002), "'Spies' lynched as Zinni flies in", The Guardian. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ "Balancing Security and Human Rights During the Intifada", Justice Undermined: Balancing Security and Human Rights in the Palestinian Justice System, Human Rights Watch, November 2001, Vol. 13, No. 4 (E).

- ^ "2000 Ramallah lynch terrorist released from prison". Ynetnews.com. March 30, 2017.

- ^ "'I'll have nightmares for the rest of my life,' photographer says". Chicago Sun-Tribune. October 22, 2000. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

I got out of the car to see what was happening and saw that they were dragging something behind them. Within moments they were in front of me and, to my horror, I saw that it was a body, a man they were dragging by the feet. The lower part of his body was on fire and the upper part had been shot at, and the head beaten so badly that it was a pulp, like red jelly.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Philps, Alan (October 13, 2000). "A day of rage, revenge and bloodshed". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ "Coverage of Oct 12 Lynch in Ramallah by Italian TV Station RAI". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. October 17, 2000. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ "Lynch mob's brutal attack". BBC News. October 13, 2000. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- ^ Whitaker, Raymond (October 14, 2000). "A strange voice said: I just killed your husband". The Independent. London. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Orlando Crowcroft (July 14, 2014). "Three Jewish Israelis admit kidnapping and killing Palestinian boy". The Guardian.

- ^ Hasson, Nir (May 3, 2016). "Abu Khdeir Murderer Sentenced to Life Imprisonment Plus 20 Years". Haaretz.

- ^ "Slain Eritrean Asylum Seeker Was Also Shot by Border Policeman, Police Say". Haaretz.com. October 26, 2015.

- ^ Tim Hume; Michael Schwartz. "Israel: 4 charged over 'lynching' of Eritrean migrant". Cnn.com.

- ^ "Israeli Man Involved in Lynching of Asylum Seeker Sentenced to 100 Days Community Service". Haaretz.com. July 4, 2018.

- ^ "Young Israelis Held in Attack on Arabs". The New York Times. August 20, 2012.

- ^ Shalizi, Hamid; Donati, Jessica (March 20, 2015). "Afghan cleric and others defend lynching of woman in Kabul". Reuters. Kabul. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "در کابل دختر 27 ساله به جرم توهین به قران به طرز وحشتناکی سنگسار و سوزانده شد!+فیلم". dailykhabariran.ir. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "بازداشت ۶ تن به اتهام کشتن و سوزاندن یک زن در کابل". BBC Persian (in Persian). BBC. March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "زنان کابل پیکر فرخنده را به خاک سپردند". BBC Persian (in Persian). BBC. March 2, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Age old rivalry behind Khairlanji violence Video". Ndtv.com. November 21, 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Béteille, Andre. "Race and caste". World Conference Against Racism.

treating caste as a form of racism is politically mischievous and worse, scientifically nonsense since there is no discernible difference in the racial characteristics between Brahmins and Scheduled Castes

- ^ Silverberg, James (November 1969). "Social Mobility in the Caste System in India: An Interdisciplinary Symposium". The American Journal of Sociology. 75 (3): 443–444. JSTOR 2775721.

The perception of the caste system as a static and textual stratification has given way to the perception of the caste system as a more processual, empirical and contextual stratification.

- ^ "Cowboys and Indians; Protecting India's cows". The Economist. August 16, 2016.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik (July 10, 2017). "Why stopping India's vigilante killings will not be easy". BBC News.

Last month Prime Minister Narendra Modi said murder in the name of cow protection is "not acceptable." ... The recent spate of lynchings in India have disturbed many. Muslim men have been murdered by Hindu mobs, ... for allegedly storing beef.

- ^ Kumar, Nikhil (June 29, 2017). "India's Modi Speaks Out Against Cow Vigilantes After 'Beef Lynchings' Spark Nationwide Protests". Time.

- ^ "India: 'Cow Protection' Spurs Vigilante Violence". Human Rights Watch. April 27, 2017.

- ^ Chatterji, Saubhadra (May 30, 2017). "In the name of cow: Lynching, thrashing, condemnation in three years of BJP rule". Hindustan Times. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ "Indian mob kills man over beef eating rumour". Al Jazeera. October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ^ "Muslim Cattle Traders Beaten To Death In Ranchi, Bodies Found Hanging From A Tree". Huffington Post India.

- ^ "Another Dadri-like incident? Two Muslims herding cattle killed in Jharkhand; five held". Zee News. March 19, 2016.

- ^ "5 held in Jharkhand killings, section 144 imposed in the area". News18. March 19, 2016.

- ^ Raj, Suhasini (April 5, 2017). "Hindu Cow Vigilantes in Rajasthan, India, Beat Muslim to Death". The New York Times.

- ^ "Beaten to death for being a dairy farmer". BBC News. April 8, 2017.

- ^ "Cow vigilantes strike in Alwar again, kill youth - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ "Rape accused dragged out of jail, lynched in Nagaland". The Times of India. March 5, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Who can stop India WhatsApp lynchings?". BBC. July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Union minister garlands lynchers, says 'honouring the due process of law', "The Times of India"

- ^ Raj, Suhasini; Nordland, Rod (June 25, 2019). "Forced to Chant Hindu Slogans, Muslim Man Is Beaten to Death in India". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ "The Hindu chant that became a murder cry". BBC News. July 10, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Bihar three men lynched, The Wire, July 20, 2019

- ^ 4 killed on witchcraft suspicion, India Today, July 21, 2019

- ^ Cone, James H. (2011). The Cross and the Lynching Tree. Maryknoll, New York: Oribis Books. pp. 134.

- ^ "Strange Fruit". Pbs.org. PBS Independent Lens credits the music as well as the words to Meeropol, though Billie Holiday's autobiography and the Spartacus article credit her with co-authoring the song.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (December 24, 2015). "Review: Quentin Tarantino's 'The Hateful Eight' Blends Verbiage and Violence". NYTimes.com. p. C1. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Plante, Chris (December 31, 2015). "The Hateful Eight is a play, and a miserable one at that". The Verge. Vox Media, Inc. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Goldfarb, Kara (May 21, 2018). "The Brutal End Of Dutchman Johan de Witt, Who Was Torn Apart And Eaten By His Own People". All That’s Interesting. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Abele, Robert (March 10, 2016). "'Admiral' makes Netherlands' military history a Hollywood-style spectacle". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Vadim Nurzhitz, Russian: Вадим Нуржиц, Hebrew: ואדים נורז'יץ, Yossi Avrahami, Hebrew: יוסי אברהמי

References[]

- Auslander, Mark, "Holding on to Those Who Can't be Held": Reenacting a Lynching at Moore's Ford, Georgia", Southern Spaces, November 8, 2010.

- "The Real Judge Lynch" (December 1901), The Atlantic Monthly

- Quinones, Sam, True Tales From Another Mexico: the Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino and the Bronx (University of New Mexico Press): recounts a lynching in a small Mexican town in 1998.

- Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America by James Allen, Hilton Als, United States Rep. John Lewis and historian Leon F. Litwack (Twin Palm Publishers: 2000). ISBN 978-0-944092-69-9.

- Etymology OnLine

- Fleming, Walter Lynwood (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 169.

- Gonzales-Day, Ken, Lynching in the West: 1850–1935. Duke University Press, 2006.

- Markovitz, Jonathan, Legacies of Lynching: Racial Violence and Memory. University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

- Before the Needles, Executions (and Lynchings) in America Before Lethal Injection. Details of thousands of lynchings

- Houghton Mifflin: The Reader's Companion to American History – Lynching

- Lynching in Georgia, New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Lynchings in the State of Iowa

- Lynchings in America

- Lyrics to "Strange Fruit" a protest song about lynching, written by Abel Meeropol and recorded by Billie Holiday

- The Lynching of Big Steve Long

- Ida B. Wells, Lynch Law, 1893

- NAACP, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918. New York City: Arno Press, 1919.

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture entry: Lynching in Arkansas

- Smith, Tom. The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans 'Mafia' Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob, crescentcitylynchings.com

Further reading[]

- Allen, James (ed.), Hilton Als, John Lewis, and Leon F. Litwack, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Twin Palms Pub: 2000), ISBN 0-944092-69-1 accompanied by an online photographic survey of the history of lynchings in the United States

- Arellano, Lisa, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community and Nation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012.

- Bailey, Amy Kate and Stewart E. Tolnay. Lynched: The Victims of Southern Mob Violence. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

- Bancroft, H. H., Popular Tribunals (2 vols, San Francisco, 1887).

- Beck, Elwood M. and Stewart E. Tolnay. "The killing fields of the deep south: the market for cotton and the lynching of blacks, 1882–1930." American Sociological Review (1990): 526–539. online

- Berg, Manfred, Popular Justice: A History of Lynching in America. Ivan R. Dee, Chicago 2011, ISBN 978-1-56663-802-9.

- Bernstein, Patricia, The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press (March 2005), hardcover, ISBN 1-58544-416-2

- Brundage, W. Fitzhugh, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press (1993), ISBN 0-252-06345-7

- Caballero, Raymond (2015). Lynching Pascual Orozco, Mexican Revolutionary Hero and Paradox. Create Space. ISBN 978-1514382509.

- Crouch, Barry A. "A Spirit of Lawlessness: White violence, Texas Blacks, 1865–1868", Journal of Social History 18 (Winter 1984): 217–26.

- Collins, Winfield, The Truth about Lynching and the Negro in the South. New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1918.

- Cutler, James E., Lynch-Law: An Investigation Into the History of Lynching in the United States (New York, 1905)

- Dray, Philip, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, New York: Random House, 2002).

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. 119–23.

- Finley, Keith M., Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965 (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2008).

- Ginzburg, Ralph, 100 Years Of Lynchings, Black Classic Press (1962, 1988) softcover, ISBN 0-933121-18-0

- Hill, Karlos K. Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Hill, Karlos K. "Black Vigilantism: The Rise and Decline of African American Lynch Mob Activity in the Mississippi and Arkansas Deltas, 1883–1923," Journal of African American History, 95 no. 1 (Winter 2010): 26–43.

- Ifill, Sherrilyn A., On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the 21st Century. Boston: Beacon Press (2007).

- Jung, D., & Cohen, D. (2020). Lynching and Local Justice: Legitimacy and Accountability in Weak States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nevels, Cynthia Skove, Lynching to Belong: claiming Whiteness though racial violence, Texas A&M Press, 2007.

- Pfeifer, Michael J. (ed.), Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

- Rushdy, Ashraf H. A., The End of American Lynching. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

- Page, Thomas Nelson, "The Lynching of Negroes – Its Cause and Its Prevention," in The Negro: The Southerner's Problem. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1904, pp. 86–119.

- Seguin, Charles; Rigby, David, 2019, "National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941". Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. 5: 1–9. doi:10.1177/2378023119841780

- Stagg, J. C. A., "The Problem of Klan Violence: The South Carolina Upcountry, 1868–1871," Journal of American Studies 8 (December 1974): 303–18.

- Tolnay, Stewart E. and E. M. Beck, A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882–1930, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press (1995), ISBN 0-252-06413-5

- Trelease, Allen W., White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction, Harper & Row, 1979.

- Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1900, Mob Rule in New Orleans Robert Charles and His Fight to Death, the Story of His Life, Burning Human Beings Alive, Other Lynching Statistics Gutenberg eBook

- Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1895, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases Gutenberg eBook

- Wood, Amy Louise, "They Never Witnessed Such a Melodrama", Southern Spaces, April 27, 2009.

- Wood, Joe, Ugly Water, St. Louis: Lulu, 2006.

- Zangrando, Robert L. The NAACP crusade against lynching, 1909–1950 (1980).

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lynchings. |

| Look up lynching in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Taking History Personnally, a text on the Marion lynching by Cynthia Carr

- Richardson, Dixie Kline. "1891 Lynching Remains a Mystery", Spencer Evening World, Spencer, Indiana, August 4, 2014

- McKee, Robert Guy. 2013. Lynchings in modern Kenya and inequitable access to basic resources: A major human rights scandal and one contributing cause. Web access

- Cotter, Holland, "‘The Legacy of Lynching,’ at the Brooklyn Museum, Documents Violent Racism", New York Times, July 26

- Mob lynching kya hai..In Hindi

- An article Concerning the lynching of numerous African-Americans in W.W. I France: New York Times, December 21, 1921

- Lynching

- Vigilantism

- Corporal punishments

- Crowd psychology

- Extrajudicial killings by type

- Attacks by method

- Terrorism tactics

- Western (genre) staples and terminology