Magnus Stenbock

Magnus Stenbock | |

|---|---|

Magnus Stenbock, Georg Engelhard Schröder | |

| Born | 22 May 1665 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Died | 23 February 1717 (aged 51) Kastellet, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Buried | Uppsala Cathedral, Uppsala, Sweden |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Swedish Army |

| Years of service | 1685–1717 |

| Rank | Field Marshal (Fältmarskalk) |

| Commands held | Kalmar Regiment Dalarna Regiment |

| Battles/wars | Nine Years' War

Great Northern War |

| Spouse(s) | Eva Magdalena Oxenstierna |

Count Magnus Stenbock (22 May 1665 – 23 February 1717) was a Swedish field marshal (Fältmarskalk) and Royal Councillor. A renowned commander of the Carolean Army during the Great Northern War, he was a prominent member of the Stenbock family. He studied at Uppsala University and joined the Swedish Army during the Nine Years' War, where he participated in the Battle of Fleurus in 1690. After the battle, he was appointed lieutenant colonel, entered Holy Roman service as Adjutant General, and married Eva Magdalena Oxenstierna, daughter of statesman Bengt Gabrielsson Oxenstierna. Returning to Swedish service he received colonelcy of a regiment in Wismar, and later became colonel of the Kalmar and then Dalarna regiments.

During the Great Northern War, Stenbock served under King Charles XII in his military campaigns in the Baltic and Polish fronts. As director of the General War Commissariat, Stenbock collected substantial funds and supplies for the maintenance of the Swedish army, earning the admiration of Charles XII. In 1705 he was appointed general of the infantry and Governor General of Scania. As acting governor, Stenbock displayed his administrative skills and organized Scania's defense against an invading Danish army, which he defeated at the Battle of Helsingborg in 1710. In 1712, he conducted a campaign in northern Germany and defeated a Saxon-Danish army at the Battle of Gadebusch, which earned him his field marshal's baton. His career plummeted after his merciless destruction of the city of Altona in 1713. Surrounded by overwhelming allied troops, Stenbock was forced to surrender to King Frederick IV of Denmark during the siege of Tönning. During his captivity in Copenhagen, the Danes revealed Stenbock's secret escape attempt and imprisoned him in Kastellet. There he was the subject to a defamation campaign conducted by Frederick IV and died in 1717 after years of harsh treatment.

Besides his military and administrative professions, Stenbock was regarded as a skilled speaker, painter and craftsman. His military successes contributed to the creation of a heroic cult in Sweden. During the age of romantic nationalism he was consistently praised by Swedish historians and cultural personalities, such as Carl Snoilsky in his poem "Stenbock's courier". His name has inspired streets in several Swedish cities and in 1901 an equestrian statue of Stenbock was unveiled outside Helsingborg city hall.

Early life (1665–1680)[]

Origin[]

Magnus Stenbock was born on 22 May 1665 in the parish of Jakob, Stockholm. He was the sixth child of Gustaf Otto Stenbock (1614–1685), member of the Privy Council and Field Marshal, and Christina Catharina De la Gardie (1632–1704), daughter of the Lord High Constable Jacob De la Gardie and sister of the Lord High Chancellor Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie. Magnus Stenbock was born a count, since Gustaf Otto Stenbock and his brothers Fredrik and Erik were made counts by Queen Christina in 1651. The Stenbock family originates from the Middle Ages. The older branch of the family was extinguished following the death of Gustaf Olofsson Stenbock in the 1490s; his daughter Anna Gustafsdotter gave birth to Olof Arvidsson, who became the paternal ancestor of the younger branch of the family. De la Gardie descended from the French-born General Pontus De la Gardie, who became a Swedish nobleman and Baron during the 1570s.[1][2]

Childhood[]

Magnus Stenbock spent much of his childhood with his siblings in the pleasure palace Runsa in Uppland; in the winters they moved to Bååtska Palace on Blasieholmen in Stockholm. When he was 10 years old, his father Gustaf Otto was deposed as Lord High Admiral after being considered to have failed in his mission and was forced to pay the extended fleet reparation of up to 200,000 daler silver coins. Gustaf Otto appeased King Charles XI, who decided to halve his fine and appointed him Admiral and commander of Western Sweden during the Scanian War. After the war, Gustaf Otto suffered from additional financial bills as a result of Charles XI's reductions and his breakdown of the old authority of the Privy Council. Gustaf Otto and Christina Catharina managed to solve their financial hardships, but were forced to pay huge sums of money to the crown. They sold large parts of the family's properties and estates, retaining only Runsa, Torpa stenhus in Västergötland and Vapnö Castle in Halland. Gustaf Otto had thus disgraced the Stenbock name and injured the King's confidence towards the family. His family's disgrace impacted Magnus Stenbock's life on a personal level and motivated him to try to restore the Stenbock name.[3][4]

Education and military service (1680–1688)[]

Magnus Stenbock was tutored at home from 1671. Firstly Haquin Spegel taught him Christianity, and reading and writing in both Swedish and Latin.[5] After Spegel, Stenbock was lectured by theology expert Erik Frykman. Frykman was succeeded by Uppsala student Olof Hermelin, who taught Stenbock between 1680 and 1684, and had a great influence on his linguistic and intellectual development. From Hermelin, Stenbock received practical oratory exercises and was lectured on leading cultural languages such as German and French, ancient history, geography, political science, law, and physical exercises such as fencing, dancing and equitation. Stenbock developed a strong interest in geometry, especially in the field of fortification, and according to Hermelin, displayed great rhetorical and linguistic talent at an early stage.[6][4]

In the autumn of 1682 Stenbock entered Uppsala University, where he and Olof Hermelin attended lectures with Olof Gardman, professor of Roman law, and Olof Rudbeck, professor of medicine. To complete his master's degree, Stenbock conducted an extensive educational voyage in Western Europe. Stenbock traveled in the spring of 1684 with a small company, partly financed by Queen Ulrika Eleonora, with Hermelin serving as host. The first destination was Amsterdam, where Stenbock practiced his language skills and undertook classes in turning. Inspired by the Dutch painters, Stenbock used his spare time to learn how to paint chickens, geese and other birds in a realistic and detailed pattern. The next destination was Paris, where Stenbock took private lectures in mathematics from Jacques Ozanam. In 1685 Hermelin left Stenbock after Christina Catharina De la Gardie withdrew her financial support.[7][8]

In the spring of 1685, Stenbock returned to the Netherlands. With the help of his cousin, Countess Maria Aurora von Königsmarck, he attained an audience with Count Gustaf Carlsson, who was commander of a Dutch regiment, and applied for a commission as ensign in his regiment. The following year Stenbock obtained a Dutch commission from William of Orange, which marked the start of his military career and the end of his travels. In 1687 Stenbock served in Stade, in the Swedish province of Bremen-Verden, as captain of an enlisted German regiment under the command of Stade's commandant, Colonel Mauritz Vellingk.[9][10]

Nine Years' War (1689–1695)[]

In September 1688 Stenbock was appointed major in the Swedish auxiliary corps led by General Nils Bielke in the Nine Years' War against France. At that time Sweden was in an alliance with the Netherlands by virtue of the guarantee treaty of 1682. In January 1689 Stenbock and the Swedish auxiliary corps, under the command of lieutenant colonel Johan Gabriel Banér, were sent to the garrison of Nijmegen. Stenbock stayed in Nijmegen while large parts of the Swedish troops were sent back to the Swedish provinces in Germany, due to tensions between Denmark and the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp. The duchy lay south of Denmark, and was allied with Sweden. In early June Stenbock and his regiment were sent to the garrison of Maastricht. In September he was granted permission by Prince Georg Friedrich of Waldeck to join the allied army as a volunteer. He experienced no battles, and when the allied army established winter quarters Stenbock traveled home to Stockholm.[11][12]

Stenbock returned to Maastricht in April 1690, and was immediately commissioned to the front lines in Wallonia in the Spanish Netherlands, where the Swedish auxiliary corps united with the 38,000-strong allied army of Prince Waldeck. On 29 June of the same year Waldeck was briefed that a French army of 35,000 men under the Duke of Luxembourg was positioned at the town of Fleurus, which came as a huge surprise in the allied field camp. The next day Waldeck's army marched towards the Sambre river, and on 1 July the bloody battle of Fleurus took place. Stenbock stood with the Swedish auxiliary corps on the right wing of the allied army, and witnessed the sound defeat of Waldeck's army at the hands of Luxembourg. During the retreat Stenbock took over the command of a Swedish battalion. He managed to bring himself and the battalion to safety from the battlefield, and took some French prisoners of war and a French standard. Waldeck suffered heavy losses, estimated at 20,000 casualties, with the Swedish relief corps effectively destroyed.[13][14]

After the battle, King Charles XI appointed Stenbock lieutenant colonel in Mauritz Vellingk's regiment in Stade. There he worked on administrative and disciplinary tasks for the daily activities of the regiment. In the spring of 1692, a new Swedish auxiliary corps was sent to Heidelberg to support the German troops at the Rhine. Hundreds of men from Vellingk's regiment were assigned to the corps, including Stenbock. Stenbock was commissioned to apply for a transit permit from the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, Charles I. At the beginning of July 1692 the commander of the allied troops at the Rhine, Christian Ernst, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, decided to cross the river to face Field Marshal Guy Aldonce de Durfort de Lorges in open battle. The Margrave commissioned Stenbock to take command of a battalion of 300 men and two cannon, and bring a transport fleet via the river route from the town of Gersheim, twenty-five kilometers south of Mainz, to the allied headquarters at Ladenburg near the Neckar's inflow into the Rhine. The journey to Gersheim was carried out without hindrance, however, halfway on the way back Stenbock was bombarded by French artillery batteries positioned at Westhofen, Mannheim and Worms. With minor casualties and several damaged ships, Stenbock was able to return to the allied camp and his operation was hailed as a success.[15][16]

At the end of August the allied army crossed the Rhine to face the French troops at the fortified town of Speyer. After two days of heavy bombardment from French cannons, the allied troops were forced to retreat, and Stenbock ended up among the troops securing the retreat. In June 1693, Stenbock returned to Heidelberg and enlisted with Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden, with whom he participated in the relief of Heilbronn. Stenbock searched for commissions in Celle, Hanover and Hesse-Kassel, and was encouraged by Louis William to court Emperor Leopold I in Vienna, in order to obtain an imperial employment. In September Stenbock was appointed colonel of the imperial army, but without a regiment, and was forced to recruit by himself. On the other hand, Stenbock was also promised a position as adjutant general in Louis William's army, which was participating in numerous operations around the Electoral Palatinate. In the spring of 1695, Stenbock was sent by the Emperor to Stockholm to present the Emperor's demand for Swedish auxiliary troops to King Charles XI, but, due to the King's indignation regarding imperial military operations in his own duchy of Palatine Zweibrücken, Stenbock returned empty-handed. In September 1696 Stenbock parted ways with the Margrave and the imperial army.[17][18][19]

Marriage and family[]

During his stay in Stockholm in 1686, Stenbock courted Eva Magdalena Oxenstierna (1671–1722). Oxenstierna was daughter of Bengt Gabrielsson Oxenstierna, President of the Privy Council Chancellery, and Magdalena Stenbock, a politically active countess.[20] Magnus and Eva exchanged letters with each other during his garrison service in Stade and in the Netherlands. Their affections for each other were conveyed, on the behalf of Stenbock, by his mother, and on behalf of Eva Oxenstierna, by both her parents and her older brother Bengt. He sent her a written proposal of marriage on 11 January 1689. As part of the arrangement, Stenbock sent his first self-portrait to her on 29 March 1689.[21] Eva accepted his proposal for marriage during the latter part of spring, when Stenbock received the portrait of Eva from her brother Bengt. In November Stenbock traveled to Stockholm to meet his future wife. The wedding took place on 23 March 1690, with the members of the Privy Council and the royal family participating. Stenbock became a favorite of Charles XI, and particularly of Queen Ulrika Eleonora. Stenbock's parents-in-law would assist him in his future career, including his imperial employment and his appointments as colonel in several Swedish regiments. Bengt Oxenstierna also used him for diplomatic assignments, in order to secure his influence on Swedish foreign affairs.[22][23]

Magnus Stenbock and Eva Oxenstierna were married for twenty-seven years, but because of Stenbock's military service before and during the Great Northern War, the couple only lived together for seven of those years. Nevertheless, they maintained a regular correspondence and Eva visited Stenbock several times in various army camps. During the first ten years of their marriage they lived off Stenbock's poor officers' salary, but during the early 18th century, Stenbock was able to collect a fortune. He sent the money, along with expensive interior decors, to Eva, which she used to buy and decorate several estates. As a landowner in Sweden, she supervised the family's finances and the children's upbringing.[24]

Eleven children were born of the marriage, of which five sons and two daughters reached adulthood:

- Gösta Otto Stenbock (1691–1693)

- Ulrika Magdalena Stenbock (1692–1715)

- Bengt Ludvig Stenbock (1694–1737)

- Fredrik Magnus Stenbock (1696–1745)

- Johan Gabriel Stenbock (1698–1699)

- Carl Fredrik Stenbock (1700)

- Carl Magnusson Stenbock (1701–1746)

- Erik Magnusson Stenbock (1706)

- Johan Magnusson Stenbock (1709–1754)

- Eva Charlotta Stenbock (1710–1785)

- Gustaf Leonard Stenbock (1711–1758)

The oldest daughter, Ulrika Magdalena, married Admiral Carl Wachtmeister, while the youngest, Eva Charlotta lived the longest of the siblings; she married Christian Barnekow, the governor of Kristianstad County. Stenbock's four oldest sons pursued military careers, while the youngest, Gustaf Leonard, became a judge and vice governor of Kronoberg County. The older sons, Bengt Ludvig and Fredrik Magnus, made their joint peregrination from the Netherlands to Paris in 1712 and were presented to King Louis XIV by the Duke of Noailles and Erik Sparre. Bengt Ludvig left his military career when he inherited and moved to the Kolk estate in Estonia, where he became a noble councillor. After his death, the estate passed over to Fredrik Magnus, who also owned Vapnö Castle, but for economic reasons he sold the castle to Georg Bogislaus Staël von Holstein in 1741. Contemporary descendants of Magnus Stenbock originate from his sons Fredrik Magnus and Gustaf Leonard.[25]

Regimental commander (1695–1700)[]

During his military service, Stenbock suffered from growing economic problems. He was forced to support the daily needs of his family in Frankfurt by sending money exchanges. Stenbock visited Kassel, where he was invited to a princely masquerade ball and received several gifts from Landgrave Charles I and his son, Prince Frederick. The Landgrave offered Stenbock a commission as equerry and colonel for a Hessian infantry regiment, but Stenbock rejected the Landgrave's offer for fear of his position with Charles XI. In January 1697 Stenbock courted Elector Frederick III at his court in Berlin to collect an old debt sent by his father to Brandenburg-Prussia in 1655. After Stenbock's audience with the Elector half of the debt was repaid, and Stenbock received the remaining 6,000 riksdaler as a deposit for a later time. He sent most of his compensation to Berlin as a money exchange to his wife. He then returned to Stade to prepare for the family's arrival, but due to sickness and economic problems, the family was forced to remain in Frankfurt.[26]

Charles XI died in April 1697 after a long illness (pancreatic cancer) and was succeeded on the Swedish throne by his son, Charles XII. At the end of May 1697, the young king appointed Stenbock to succeed Jakob von Kemphen as regimental colonel and commandant in Wismar. After redeeming a wage claim of 3,000 riksdaler at the imperial court in Vienna, Stenbock could pay his family's debts to creditors in Frankfurt and in August the family moved into the commandant's residence in Wismar. As commandant, Stenbock was responsible for the repair of Wismar's defenses. His regiment in the city consisted of about 1,000 German infantry recruits. Stenbock also spent time writing a war manual called Den svenska knekteskolan (The Swedish Soldier's School), which described different infantry tactics, march techniques, the use of military barriers, and basic fortification. He never completed his writing for publication. On 2 January 1699 Stenbock was appointed colonel of the Kalmar Regiment. A few weeks later, Stenbock and his family moved to the colonel's residence of Kronobäck in Småland. On 16 February 1700, Stenbock was appointed colonel of the Dalarna Regiment by the King. This was made possible thanks to Count Carl Piper, after his wife Christina Piper's recommendation, when Magdalena Stenbock gave Christina a pair of precious earrings.[27] Before Stenbock was able to move into his new colonel's residence in Näs Kungsgård, close to the Dalälven, his regiment received orders to mobilize and march south to Scania, in conjunction with the start of the Great Northern War.[28][29]

Great Northern War (1700–1713)[]

Campaign in Denmark and the Baltics[]

The Great Northern War began on 12 February 1700, when the King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, August II, crossed the Daugava river with his Saxon troops and besieged the city of Riga in Swedish Livonia. Simultaneously, King Frederick IV of Denmark ordered his Danish troops to invade Holstein-Gottorp. Russia entered the war on August the same year, and on September, Russian troops under Tsar Peter I invaded Swedish Ingria and besieged the outpost of Narva in Estonia.[30]

Stenbock was ordered to immediately join his regiment that was marching towards Scania. He arranged field equipment in Stockholm and joined his regiment in Köping. Stenbock bid farewell to his family in Växjö, and his regiment arrived at Landskrona in July to await embarkation for further transport to Zealand. On 25 July Swedish troops led by the King landed at Humlebæk, where the Danish defenders were quickly routed, and the Swedes established a bridgehead on Zealand. Two weeks after the landing, Stenbock and the Dalarna Regiment arrived on Zealand, strengthening the Swedish force there to about 10,000 men. This forced Frederick IV to withdraw from the war on 8 August 1700 with the treaty of Traventhal. Stenbock and his regiment were shipped back to Scania in late August.[31][32]

In early October, Stenbock sailed with the Dalarna Regiment to Pernau, and joined Charles XII and the Swedish main army on the march towards Narva. On 20 November, the Swedish main army arrived at the outskirts of Narva. Through reconnaissance the Swedes learned that the Russians, who were about 30,000 strong including thousands of camp followers, had built a fortification system that stretched in a semicircle between the north and south sides of the city. Lieutenant general Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld took command of the army. He drafted a battle plan where two Swedish columns would attack and break through the fortification line, and each column would then move to the south and north along the line and roll up the Russian defense so that the Russian army would be trapped in two pockets against the Narva River. Rehnskiöld himself commanded the left column while General Otto Vellingk commanded the right column. Within Rehnskiöld's column, Stenbock was appointed to command an advance guard of 516 men, consisting of about fifty grenadiers, a battalion of dalcarlians (soldiers of the Dalarna Regiment) and a supporting battalion from a Finnish regiment. Stenbock and his troops spearheaded the first wave of Swedish attacks.[33][34][35]

The Battle of Narva took place on the afternoon of 20 November. The two Swedish columns, hidden by a heavy snowstorm that blew directly into the eyes of the Russians, violently breached the Russian fortifications. The two breakthroughs of the fortification system caused panic among the Russian troops, and after a wild rout the Russian army chose to surrender. After negotiations they were allowed to withdraw back to Russia. About 9,000 Russian soldiers died during the battle, and their entire command was captured, while the Swedish casualties were estimated to be around 1,900 men. Among Stenbock's troops, about 60 were killed and 149 were severely wounded; Stenbock himself was hit in the leg by a musket ball. The commander of the Russian army, Duke Charles Eugène de Croÿ, and several senior officers surrendered themselves to Stenbock, who personally brought them to the King's camp as prisoners of war.[36][37][38]

Stenbock was bedridden for two weeks after the battle. Just a few days later, Charles XII visited his sickbed, congratulated Stenbock for his bravery and promoted him to major general of infantry. During December, the main Swedish army overwintered outside the town of Dorpat and the dilapidated Laiuse Castle. On the way to the castle, Stenbock accompanied the state secretary Carl Piper in his wagon, which meant that Stenbock now stood in the King's innermost circle. On 25 December Charles XII ordered Stenbock to take 600 men and four cannons into Russian territory, with the aim of occupying the city of Gdov on the other side of Lake Peipus. On 29 December Stenbock started his march with 300 Finnish cavalry units and an equal number of infantry units, mostly dalcarlians travelling on sleds with five men each. After five days they encountered an advance guard of about 300 Russian dragoons. With the help of his field artillery, Stenbock repelled the Russian attacks and continued his march. During the night after the battle, Stenbock and his troops were hit by a blizzard. The combination of overwhelming Russian troops deployed around them and the persistent cold weather forced Stenbock to retreat to Estonian soil. He burned down villages in the area surrounding Gdov and, after several skirmishes with Russian troops, returned to the main Swedish army on 6 January 1701. Upon return to the royal camp, only 100 of his 600 men were combat effective.[39][40][41]

Throughout the winter and spring of 1701 Stenbock courted Charles XII and maintained his regiment. On 28 January the Swedish army command gathered in Stenbock's quarters at the Laisholm estate, where Stenbock and his regiment arranged a large feast and a theater performance, with songs celebrating Charles XII and his victory at Narva. At this time, Stenbock was nicknamed "Måns Bock" (Måns the buck), "Måns Lurifax" (Måns the sly dog) and "Bocken" (billy goat) by Charles XII.[42][43][44][45] On 8 March Stenbock arranged an advanced snowball fight where hundreds of soldiers fought against each other in a simulated siege, later concluding with Stenbock exercising his dalcarlians in front of the King. Stenbock's ventures were highly appreciated by the King, who awarded him with a magnificent horse and appointed him general drill instructor to every infantry regiment during the winter break. His drills, partly based on pages from his unfinished war manual, laid the foundation for a new infantry regulation issued during the spring of 1701. Stenbock was also praised by Bengt Oxenstierna, who in letters to Stenbock urged him to offer advice to the King, and to persuade him to commence peace talks with the hostile states to sustain the balance of power in Europe.[46][47]

Campaign in Poland[]

With reinforcements from the Swedish mainland, the Swedish main army broke camp in June and marched south towards Riga to confront King Augustus II's Saxon and Russian troops. By 7 July the army was outside Riga. Charles XII and Rehnskiöld planned to cross the Daugava river right next to the city and assault Augustus II troops on the opposite shore. In the Swedish battle plan, drafted by Rehnskiöld, Carl Magnus Stuart and Erik Dahlbergh, the troops were ordered to collect landing boats near Riga and construct floating batteries. The batteries would convey infantry units across the river to establish a bridgehead. During the operation on 9 July, Stenbock assisted in the construction of a floating bridge to allow the cavalry to cross the river. However, strong currents caused the floating bridge to be destroyed, and by the time it was repaired it was too late to influence the outcome of the battle. The crossing was still a success, but Stenbock's efforts were overshadowed. The main army occupied Courland and overwintered at the castle of Würgen outside of Libau.[48][49]

Since Charles XII failed to defeat Augustus II during the Daugava operation, he decided to carry out a military campaign on Polish territory to defeat Augustus' army, and secure his own back before attacking Russia. Stenbock received a memorandum regarding the war situation and Sweden's foreign policy from Bengt Oxenstierna, who shortly before his death, entrusted Stenbock to present it to Charles XII and persuade the King to end his campaign against Augustus II and instead direct his attention towards the Russian border. However, Charles XII went his own way and, by the end of January 1702, the Swedish main army had entered the Lithuanian part of Poland. Charles XII marched against Warsaw with the bulk of his army, while Stenbock and the Dalarna Regiment were sent to Vilnius in March along with major general Carl Mörner and the Östergötland Cavalry Regiment. Stenbock and Mörner was tasked with hunting down the troops of Grzegorz Antoni Ogiński and Michał Serwacy Wiśniowiecki, and with collecting contributions for the main army's maintenance. Vilnius was taken during late March, and the Swedish garrison was subsequently reinforced. During the Battle of Vilnius on 6 April the garrison was overwhelmed by Wiśniowiecki's troops. However, following vicious fighting inside the city, the attackers were repelled with the loss of 100 men, while the Swedish garrison lost 50 men.[50][51]

Mörner and Stenbock were ordered to bring their 4,000 troops from Vilnius to Warsaw. The march across central Poland was obstructed by skirmishes against Wiśniowiecki's troops and wide rivers. On several occasions Stenbock used his engineering skills to build bridges, and the Dalarna Regiment served as sappers both in Stenbock's and Charles XII's marches.[52] In July 1702 Charles XII and his main army caught up with Augustus II at the village of Kliszów, northeast of Kraków. Mörner and Stenbock reunited with the main army on the evening of 8 July. On the following morning Charles XII and the main army attacked Augustus II's Saxon and Polish troops. Stenbock was stationed with the infantry on the center of the first line of attack, under the command of lieutenant general Bernhard von Liewen. When Saxon and Polish cavalry attacked the Swedish left wing, Charles XII reinforced it with some cavalry squadrons and with Stenbock and the Dalarna Regiment. The cavalry attack was repulsed, and the Swedish main forces advanced into the Saxon camp, took control of the Saxon artillery, and threatened to encircle the Saxon center. Augustus II was forced to retreat, and lost about 4,000 men, while the Swedish losses were estimated at 1,100 men. Later, Stenbock recalled the battle as the most difficult he had ever experienced.[53][54][55]

After the battle of Kliszów, Charles XII spread his troops around Kraków to cut off Augustus II's line of retreat. But since Augustus II was already far away from the area, Charles XII decided to take Kraków. He sent Stenbock with a contingent of dalcarlians and cavalry units from the Småland Cavalry Regiment to scout the city, and ordered Stenbock to persuade its commandant, starost Franciszek Wielopolski, to open the city gates. During Stenbock's advance on 1 August, his troops were bombarded by cannon from the city walls, killing six of his cavalry. A squad managed to reach the city gate, and Stenbock negotiated with Wielopolski, who refused to give up Kraków. At the same time, Charles XII arrived with a contingent of Life Guards, whom he ordered to open the gate by force. After a short battle, Charles XII and Stenbock broke into the city, killing its sentries, and captured Wielopolski.[56][57][58][59]

As a token of appreciation for his services, Stenbock was appointed Commandant of Kraków. He was commissioned to collect a contribution of 60,000 riksdaler from its citizens. In two days Stenbock's patrols collected the entire amount, including large amounts of cattle and grain. Pleased with his effort, Charles XII donated 4,000 riksdaler from the contribution to Stenbock as a personal gift and assigned him the role of "le Diable de la Ville" (the Devil of the city). Stenbock was installed at the Wawel Castle and became the highest Swedish representative in Kraków. During his stay, Stenbock maintained a fitting banquet for the King, his generals and foreign envoys, and sent regular deliveries of spoils and gifts back to his wife in Stockholm.[60][61][58]

Director of the General War Commissariat[]

On 18 August 1702 Stenbock was appointed to succeed Anders Lagercrona as director of the newly established General War Commissariat, and became responsible for the main army's food supply. With the help of war commissary Jöran Adlersteen, Stenbock decentralized the maintenance of the Swedish troops by appointing a commissary to each regiment, in order to monitor and record the collection of supplies.[62] On 19 October Stenbock was ordered to personally command a contingent of 3,000 men to Galicia southeast of Kraków. His task was to collect substantial contributions, and to force the local magnate Hieronim Augustyn Lubomirski and other Polish nobles to renounce their allegiance to King Augustus. He sent war commissars with proclamations about his collection to the villages and cities around Galicia, but when several commissars returned empty handed, Stenbock took severe measures. On 28 October he set an example by burning down the city of Pilzno. Between November and December the villages of Dębica, Wysoka, Wesola and Dub were burned on Stenbock's orders, acknowledged by Charles XII in their letter correspondence. In December Stenbock executed an expedition south to Krosno, but he soon returned to Reschow and travelled on to Jarosław. In January 1703, he continued across Oleszyce and Uhniv to Belz, and in February he passed Tyszowce and arrived at the fortified city of Zamość. Since he lacked troops and siege artillery to attack the city, he continued to Chełm and rejoined the main army in Warsaw on 28 February. From Galicia, Stenbock collected over 300,000 riksdaler, including seventy wagons loaded with grain, slaughtered cattle and clothes. Stenbock filled his own coffers with church silver, which he sent with personal greetings to churches and friends in Sweden. Stenbock's expedition led to a strong anti-Swedish sentiment amongst the Galician nobility, a mood which over the years continued to grow throughout Poland.[63][64][65]

On 21 April 1703 Stenbock participated, along with Charles XII, in the Battle of Pułtusk against the Saxon Field Marshal Adam Heinrich von Steinau. On May of that year, Charles XII laid siege to Thorn on the Weichsel river. Since he lacked siege artillery, Charles XII ordered cannons and equipment from Riga and Stockholm, which had to pass through Danzig at the mouth of the Weichsel. Stenbock was sent incognito to Danzig to negotiate with the city's magistrate about a free passage for the Swedish transport vessels. At the end of July the transport fleet from Riga arrived at Danzig with 4,000 Swedish and Finnish recruits. Even though Stenbock was granted a contribution of 100,000 riksdaler, the city refused to open its harbor barriers for the Swedish vessels and Stenbock was forced to transport the siege artillery by land. He arrived at the Swedish field camp at Thorn with the artillery at the end of August. The city was bombarded during the autumn and, on 3 October, the city's garrison surrendered to Charles XII. In December a new conflict with Danzig was triggered by Stenbock attempting to recruit troops around the area, even though freedom from enlistment was one of Danzig's privileges. However, Charles XII demanded that recruitment must be allowed, and the city submitted to his demands in January 1704. Subsequently, however, the King further demanded a refund of 15,000 silver marks which the exiled Charles VIII of Sweden offered to the city nearly 250 years earlier in return for fishing revenue from Putzig. Members of the Gyllenstierna family had already presented the demands as heirs to Charles VIII the previous year, and Stenbock and the King returned to Danzig to press Gyllenstierna's demands. Eventually the city relented and paid 136,000 riksdaler in exchange for a letter of safe conduct from Charles XII.[66][67][68][69]

In 1704 Stenbock was commissioned to set up his own dragoon regiment. At first the regiment amounted to 600 men, which was expanded to 1,000 men in 1707. At the end of August 1704 Stenbock accompanied the King during the occupation and plundering of Lemberg in the southeast of Poland. During Charles XII's continued campaign against Augustus II, Stenbock commanded the King's vanguard, comprising the Dalarna Regiment and other regiments. He was also tasked with collecting contributions and establishing supply depots. On the way to Warsaw, the city of Krasnystaw was burned down by Stenbock. The main army overwintered around Rawicz near the border of Silesia, where Stenbock was responsible for accommodation and provisioning. On 4 November Stenbock was promoted to lieutenant general of infantry, which he regarded as an important acknowledgment. On 15 November Stenbock's mother Christina Catharina died and he inherited Vapnö Castle.[70]

During the winter months between 1705 and 1706, Stenbock accompanied Charles XII and the main army in the blockade of Grodno in Polish Livonia, which was occupied by a Russian army under the command of Georg Benedict von Ogilvy. In August 1706, Stenbock marched with Charles XII and the main army into Saxony for a final resolution with Augustus II. On 14 September the treaty of Altranstädt was signed. Augustus II was forced to break all ties with his allies, renounce his claims to the Polish crown, and accept Stanisław I Leszczyński as the new King. The Swedish army stayed in Saxony for a year, where Charles XII prepared and mobilized his army to go east and fight against Russia, though this time without Stenbock. Earlier in July Stenbock had been promoted to general of infantry and had succeeded Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld as Governor-General of Scania on 25 December 1705. In April 1707 he held his last audience with Charles XII; on his way home to Sweden he visited the health resort of Karlsbad in Bohemia to treat his kidney stone disease.[71][72]

Governor-General of Scania[]

On 4 June 1707, Stenbock arrived in Malmö and reunited with his family at Rånäs Manor, which his wife acquired in 1704. He entered the governor's post on 18 September. At that time, the province was severely crisis-ridden, partly because it was close to Denmark and was depleted of able-bodied men throughout the years of the war, and partly because of administrative mismanagement. Stenbock's predecessor, Rehnskiöld, had remained outside of the province since the outbreak of the war in 1700, and hence Scania's administration had passed over to the deputy-governor, Axel von Faltzburg. von Faltzburg was considered an invisible leader due to his weakness, corruption and disinterest, so administrative responsibilities were distributed between various bailiffs and officials, who spent their time in turf wars, despoilments and arbitrary exercises of power, which angered the Scanian peasantry.[73][74]

Stenbock's first act was to inspect the provincial office reports, where he discovered that the financial accounting was in disarray and that the urbaria had not been updated for over 20 years. He replaced von Faltzburg with his own family companion and accountant, Peter Malmberg. In October and November 1707 Stenbock undertook an extended inspection tour of the cities and villages across Scania, to obtain fresh recruits and form an opinion of the situation in the province. He was told that the peasants were pressured to pay unreasonably high taxes by the officials, whose ruthless conduct had caused over a thousand rural settlements to lay desolated. Stenbock reported on the situation to the Privy Council in Stockholm, suggesting that a state commission of inquiry should be assigned in Scania to investigate the number of officials being accused of corruption. The Privy Council approved his proposal in February 1708, which resulted in several corrupt bailiffs and officials being discharged and arrested. In addition to his work within the commission of inquiry, which occupied much of his time, Stenbock attended to other matters, including: combating shifting sand afflicting coastal farms, erecting milestones on the royal highways, planting trees to resolve the growing shortage of wood, and hiring land surveyors from Stockholm for the necessary provincial measurement.[75][76]

Stenbock spent his time with his wife and family in various properties and estates: in the governor's residence in Malmö which was used for representation; in the crown's property of Börringe in Scania; in Rånäs, where the couple controlled a huge farm and built a new mansion; and in Vapnö, where Stenbock spent his time with artistic activities and his wife took care of the daily operation of the estate and its stud farm, and established a wallpaper printing house where they produced wallpaper for sale. The couple congregated with Scanian landlords during dinners and hunting parties. Stenbock visited the spa in the village of Ramlösa, which was inaugurated as a health resort on 17 June 1707 by the provincial physician of Scania, Johan Jacob Döbelius. Since the source of the well, according to Döbelius, had a medicinal effect, Stenbock saw a personal incentive to support it, since he suffered from kidney stone disease. Stenbock supported ground clearance around the spa and its decoration with a wooden duckboard and some primitive wooden buildings.[77][78]

On the late summer of 1709, Stenbock received recurring reports from Envoy Anders Leijonkloo regarding a rapid increase of Danish military activity in Copenhagen, with Danish warships being loaded with troops and supplies. These signs suggested that the Danes were preparing for an invasion.[79]

War in Skåneland[]

News of the disastrous defeat of Charles XII at the hands of Peter I and his army at the battle of Poltava in Ukraine, on 28 June 1709, spread across the Swedish empire throughout that summer of 1709. Charles XII managed to escape across the border to the Ottoman Empire, accompanied by roughly 1,000 men, but the remnants of his army surrendered at the village of Perevolochna near the Dnieper river. The defeats at Poltava and Perevolochna resulted in the deaths of 7,000 Swedish soldiers and the capture of 23,000 soldiers and non-combatants. With the Swedish main army destroyed, Denmark and Saxony returned to the war, forming a new coalition against the Swedish empire. Saxon troops entered Poland to recapture the royal crown of Augustus II, whilst Danish-Norwegian troops under Frederick IV invaded Scania and Bohuslän.[79]

After receiving Leijonkloo's reports of Danish rearmament, Stenbock summoned a meeting with several dignitaries from Malmö. He urged that the city's defenses must be strengthened and food and reinforcements acquired in preparation for a siege, since Malmö formed a strategic key point for the dominion of Scania and the defense of the Swedish mainland. Landskrona was also in need of reinforcement, and Stenbock appealed that a provisional fortress should be built in Kristianstad to prevent the Danes from moving into Blekinge. However, the fortifications of Helsingborg were dilapidated to the extent that the city was deemed impossible to defend. The coastal guard was reinforced, and beacons were erected at Barsebäck, Råå and other exposed stretches along the Öresund coast, where Stenbock expected the Danes would land. Apart from the fortress garrisons, Stenbock had only a few regiments at his disposal, and most of their men were poorly equipped. On 22 August Stenbock reported the Danish threat to the Defense Commission. The commission agreed to send three cavalry regiments from Västergötland to Scania's defense, and in October, they reassembled both the Northern and Southern Scanian cavalry regiments, who previously been wiped out at Poltava. Stenbock himself mustered 3,000 fresh troops. In September he issued a general declaration calling the people of Scania to fidelity to the Swedish King, in order to prevent pro-Danish guerrilla organization and collaboration. On 27 September 1709, Stenbock made an inspired speech to the citizens of Malmö, dispelling their concerns about the loss at Poltava and reminding them of their duty to their King and fatherland. Addressing the people of Scania as brethren, he was prepared to die by their side.[80][81]

You all know how the great Kings of Sweden, Charles X Gustav and Charles XI, strived to [...] preserve this duchy and this fortress, as one of the foremost jewels within the royal Swedish crown. Still, they have never exempted themselves from wearing bloody shirts like their brave men, who let their blood flow on the sandy hills of Copenhagen, Halmstad, Lund and Landskrona. [...] Since we own a King, who with the same care watches over our well-being, why should we step away from the famous footsteps of our ancestors? I am a living witness to the good intent of His Royal Majesty, in which I for seven consecutive years have witnessed him, with peerless courage, march straight towards his enemies, in order to obtain a safe and lasting peace for his faithful subjects; thus leaving each and every one to judge, whether something would be more to our interests than to, with our faithfulness, reward His Majesty's untiring effort in his difficult campaign, and assert his immortal praise with valor. And since this duchy might be called the key to the Kingdom of the Swedes, including this fortress to the duchy, I will, as the governor of this domain, regard this as my greatest duty, that through the protection of this city, I will safeguard the welfare and property of each and every one of you, and I shall also have lives and blood unspared at all times, in my belief that you as well from now on, as honest men and faithful subjects, show your willingness in unadulterated fidelity. Thus, I am watchful of my most gracious King and fatherland, and I want to share the danger and pain with you through all ends, thereon, I bear witness to the living God.

— Magnus Stenbock[82]

Danish campaign in Scania and Blekinge[]

The Privy Council in Stockholm received the Danish declaration of war on 18 October. By then the fortifications along the Öresund coast had been made moderately defensible, especially in Malmö where the garrison had been expanded to 3,550 men. Three cavalry regiments were positioned along the Öresund coast under Colonel Göran Gyllenstierna's command, and both Malmö and Landskrona had enough ammunition and supplies to withstand a six-month siege. On 31 October more than 250 transport vessels sailed from Copenhagen, escorted by 12 warships led by Admiral Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve. The Danish invasion army consisted of 15,000 men with Christian Ditlev Reventlow as commanding general. Stenbock discovered the fleet from Malmö Castle on 1 November, and a signal shot from Landskrona reported that the Danish armada had anchored at Råå, south of Helsingborg. At the sound of the signal shot, the cavalry regiments marched towards the site and positioned themselves at the villages of Raus, Katslösa and Rya; Stenbock establishing his headquarters at the latter. Upon discovering elite Danish troops at Råå, covered by Danish warships, Stenbock decided to retreat to the southeast, destroying all the bridges along the way. By 5 November the invasion army was in full force, and took Helsingborg without resistance.[83][84]

In November the Danes occupied central Scania and established supply routes from Ängelholm to Ringsjön. At the end of November, Malmö was blockaded by a Danish contingent of 2,000 men, while Landskrona was encircled in early December. Since the Danes lacked siege artillery, their plan was to starve out the Swedish garrisons. Stenbock was ordered by the Defense Commission to leave Malmö on 9 December to take command of a newly organized Swedish field army, which would muster and march south towards the assembly point at Loshult. The defense of Malmö was handed over to major general Carl Gustaf Skytte and Stenbock left the city on 1 December escorted by a small company. On 7 December he established his headquarters in Kristianstad. Due to problems with supply chains, Stenbock wanted to carry out a rapid campaign to prevent the Danes from establishing a safe base of operations in southern Sweden, but he was ordered by the Defense Commission to hold his positions in northern Scania before the arrival of the Swedish field army. On 3 January 1710 Reventlow began his march towards Kristianstad with a contingent of 6,000 men and eight guns, under orders from Frederick IV to capture Karlskrona and burn the Swedish battle fleet. On Epiphany, Stenbock was briefed of this and ordered his troops from Kristianstad to transport army supplies to Karlshamn and to various villages in Småland. While he organized defenses in Karlshamn with General admiral Hans Wachtmeister and the governors of Blekinge and Kronoberg counties, he handed over the command of the troops to Göran Gyllenstierna, who positioned the troops at fords and strategic points along the Helge River. The position at Torsebro was attacked by Danish troops on 13 January. Gyllenstierna was forced to retreat, and his rearguard fought against Danish cavalry units at Fjälkinge. After the battle, about 60 Swedes were killed and an entire battalion from the Saxon infantry regiment was captured. Eastern Scania and several Swedish food stores ended up in Danish hands.[85][86][87]

Stenbock gathered his remaining troops and established his headquarters in Mörrum. There he received permission from the Defense Commission to organize levy recruits on 17 January, and received free rein to attack when the opportunity was favorable. The troops gathered in Ronneby on 18 January, whence the infantry was sent to Karlskrona's defense. Gyllenstierna was assigned a cavalry contingent and was ordered to destroy bridges and obstruct Danish movements in Blekinge. On 20 January Stenbock went to Växjö to assemble the field army, since Loshult was considered an insecure assembly point. On 19 January, Reventlow entered Blekinge and conquered Karlshamn, seizing army supplies and 12,000 riksdaler from its citizens. The Danes withdrew on 24 January and established winter quarters from Ängelholm to Sölvesborg. On 21 January, Stenbock arrived in Växjö, where he met with lieutenant general Jacob Burensköld, some companies from Östergötland Infantry Regiment, and 150 levies from Småland. Reinforcements arrived in stages during the next few days, consisting of the newly assembled Uppland, Kronoberg, Jönköping, Kalmar, and Östergötland and Södermanland infantry regiments, as well as Adelsfanan, Horse Life Regiment, Småland and Östergötland cavalry regiments. The army was well-equipped but was short of swords and several soldiers lacked basic uniforms. On 31 January, Stenbock broke camp and a few days later his army encamped at Osby. On 8 February, major general Christian Ludvig von Ascheberg joined the army along with the Älvsborg Regiment, Saxon Infantry Regiment and Queen Dowager of the Realm's Horse Life Regiment, as well as bringing field guns and several ammunition wagons. On 11 February, Gyllenstierna arrived with his three cavalry regiments from Blekinge. Stenbock was now in command of 19 regiments and about 16,000 men.[88][89][87]

Swedish counteroffensive and the Battle of Helsingborg[]

On 12 February, the army broke camp at Osby and marched south. The same day Swedish troops met with a Danish reconnaissance patrol of 200 cavalry units under lieutenant general Jørgen Rantzau in the forests of Hästveda. After a short and confused battle, the Danes withdrew with the loss of forty soldiers, while the Swedes lost between three and ten soldiers. When Reventlow was informed of the battle and the march of the Swedish troops, he decided to retreat with his troops to Vä and later to Skarhult. Stenbock's movements were a diversion, as he had divided his field army into two columns that marched towards Hästveda and Glimminge, in order to trick Reventlow by threatening his headquarters in Kristianstad and force him to retreat to Helsingborg. Reventlow, however, marched south to Barsebäck, where the Danes had a good retreat route across the strait and could at the same time continue their encirclement of Malmö and control the southern plains of Scania. During a night-time reconnaissance at Ringsjön, Reventlow caught a severe cold and high fever, and he appointed lieutenant general Rantzau as his deputy on 17 February.[90][91]

On 18 February, Stenbock crossed the River Rönne at Forestad and Hasslebro. At Trollenäs Castle, the Uppland cavalry regiment encountered 300 Danish dragoons, who withdrew after a short battle. The next day, Rantzau positioned his army at Roslöv north of Flyinge, and ordered the troops besieging Malmö to withdraw immediately. After an emergency meeting with his generals on 19 February, Rantzau ordered his troops to return to Helsingborg. When Stenbock was informed that the Danes had passed Stora Harrie, he decided to pursue them and divided his army into five columns. On 20 February, Stenbock's cavalry encountered the Danish rearguard at Asmundtorp, but Stenbock called them off and withdrew to Annelöv and Norrvidinge, since the cover of darkness and Danish shelling halted the Swedish advance. Stenbock himself galloped to Malmö to resupply, and on 24 February he returned to the army with food, reinforcements and 24 artillery pieces. He was informed that the Danes had made battle preparations at Helsingborg and, following a council of war with the high command, Stenbock decided to seek a confrontation with the Danes. His troops decamped from Norrvidinge on 26 February and made an evasive movement towards the heights north of Helsingborg, setting up camp at Fleninge Church the following day. Stenbock established his headquarters in Hjälmshults kungsgård a few kilometers west. The troops prepared to march at midnight and carried out an evasive movement south through Ödåkra and Pilshult.[92][93]

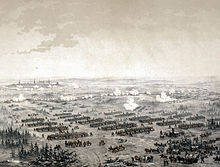

On the morning of 28 February Rantzau and the Danish army of 14,000 men and 32 guns were positioned on a front which stretched three kilometers in a north to south direction from Pålsjö forest and the Ringstorp Height to Husensjö. The troops were protected by impassable semi-frozen marshlands. Stenbock's army, which also consisted of 14,000 men and 36 guns, was formed in a line between Senderöd and Brohuset. In order to get past the marshlands, Stenbock made a very time-consuming maneuver that finally placed the Swedish left wing between Brohuset and Filborna. Stenbock's maneuver succeeded in causing the Danes to leave their favorable position to avoid risking encirclement. Rantzau ordered the Danish right wing to advance, which started a furious cavalry fight. The Danes had the upper hand and the Swedish cavalry suffered heavy casualties. But since the Danish right wing advanced too quickly, the Danish infantry and artillery fell behind. When they subsequently formed a new line of attack, confusion arose among the ranks, and Stenbock discovered a gap between the Danish right wing and center. He ordered an attack against the Danish center, and after heavy resistance the Danish line fell apart. During the battle's final stages, the Danes fled to Helsingborg's fortifications with Swedish cavalry units in pursuit. After three hours of battle, the Danish losses amounted to 1,500 dead, 3,500 wounded and 2,700 prisoners. Among Stenbock's troops, 900 were dead and 2,100 were wounded. Lieutenant general Burensköld was captured but was exchanged a few weeks later, and Stenbock injured his back when he accidentally fell from his horse in a swamp.[94][95][96][97]

The Danes entrenched themselves in Helsingborg and transported the wounded soldiers, together with the city's women and children, to Helsingør. Rantzau handed over command to major general Frantz Joachim von Dewitz. Stenbock refrained from storming the city and on 1 March he installed a battery at Pålsjö beach, which bombarded the Danish ship traffic. On 3 March, Stenbock began the bombardment of Helsingborg, destroying much of the city. Frederick IV ordered von Dewitz to evacuate the city immediately and transport the troops to Zealand, and the Danish evacuation began the following day under intense Swedish artillery fire. The Danes burned their carriages, threw away their food stores and slaughtered thousands of horses which they left in the streets, basements and wells of the city. On 5 March, von Dewitz was the last Dane to leave Scania on a boat. At the entrance of the reclaimed city, Stenbock was forced to command farmers to dispose of the horse carcasses, which were buried in mass graves or dumped in the sea. Stenbock left the city on 9 March and reunited with his family in Malmö.[98]

After Stenbock's victory at Helsingborg, a heroic cult began to grow around him in the Swedish empire. He received personal congratulations from the Queen Dowager Hedvig Eleonora, Princess Ulrika Eleonora, Duke Charles Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp, King Stanisław Leszczyński and the Duke of Marlborough. Throughout the Kingdom, Stenbock's victory was celebrated with tributes, writings and artistic works, and a general thanksgiving ceremony was held on 18 March, where Stenbock's name was praised. In April, Stenbock traveled to Stockholm to inform the Privy Council about the new strategic situation. On arrival, he was hailed by the citizens of Stockholm and he held several victory speeches before the clergy and peasant estates. The Riksdag of the Estates offered him the Bååtska palace, and on 21 May the Privy council appointed him field marshal, sending the letter of appointment to Charles XII in Bender for the King's signature.[99][100]

Plague outbreak[]

Stenbock's field army garrisoned in the Scanian cities and villages, in order to defend against Danish marines, who looted the coastal villages between Kullen and Barsebäck during the spring. In the summer of 1710 Sweden was hit by a bad harvest, and starving soldiers in Scania were forced to steal food from the peasants. Stenbock could not maintain their discipline and demanded food deliveries from other parts of the Kingdom. At the same time, he received news from Stockholm and Blekinge about strange deaths. On 10 September the Privy Council sent a message to all governors around the Kingdom that Stockholm was suffering from a severe infection that was killing people by the hundreds. Afterwards, the Collegium Medicum determined that the epidemic in Stockholm was the dreaded bubonic plague, that had ravaged the southern and eastern coasts of the Baltic Sea since autumn 1708. These signs forced Stenbock to isolate the entire Scanian region from the outside world to keep the epidemic at bay. On 28 October armed barricades were placed on the major highways to Scania from Halland, Småland and Blekinge, and sentries were posted at Margretetorp, Markaryd and Kivik. Smoking stations were erected at the barricades and travelers to Scania were forced to present a valid bill of health and to allow their clothes and luggage to be fumigated with cleansing herbs before they could enter the region. Letters from postal offices were also fumigated. Between 1710 and 1713, 100,000 people in Sweden succumbed to the plague, of which 20,000 were in Stockholm. Thousands of people died in Scania, mainly in Göinge and the northeastern parts of the region, while neighboring villages were free from plague-related deaths.[101]

Royal Councillor[]

In February 1711 Stenbock received a royal order from Charles XII, dated 30 August 1710, to resign from his governor post and install himself in Stockholm as Royal Councillor and member of the Privy Council. His letter of appointment as field marshal was omitted and Burensköld was appointed as the new governor. Stenbock regarded this as an insulting downgrade, partly because, due to the Kingdom's poor economic state, he would now receive an uncertain salary as royal councillor compared to his stable income and benefits as Scanian governor, and partly because, unlike his subordinate generals, he was not promoted after the victory at Helsingborg. However, Stenbock would still be responsible for Scania's border defense, and received a royal order to build fortifications outside Barsebäck, Höganäs and Mölle, as well as a two-kilometer-long mound at Råå. Between 1711 and 1712 Stenbock was appointed chancellor of Lund University.[102][103]

In Bender, Charles XII made revenge plans against Russia, and convinced the Ottoman government in the Sublime Porte to ally with Sweden. He gave orders to the Privy Council to send a field army to Pomerania, which would enter Poland from the west, while Charles XII would march from the south in command of an Ottoman army. The united armies would once again dethrone Augustus II, march against Moscow, and force Denmark to an unfavorable peace treaty. Council President Arvid Horn and Field Marshal Nils Gyllenstierna opposed the King's plans and, in spring 1710 ratified a declaration of neutrality with the Western powers of Europe in The Hague, favoring the Swedish dominions in Germany. Since Charles XII regarded Horn as unreliable, he entrusted Stenbock with putting together and overseeing a new field army. In his first council session in April 1711 Stenbock pleaded for the King's order, which was criticized by Horn and several other council members. Stenbock was supported in this matter by Hans Wachtmeister and Stanisław Leszczyński, who had sought protection in Swedish Pomerania, and was granted an annual appanage by the King, a decision which angered the council. When Denmark, Russia and Saxony learned of Charles XII's dismissive attitude towards the declaration of neutrality, a Danish army of 30,000 men entered Pomerania through Mecklenburg in August 1711, while Saxon troops marched from the south. Frederick IV and Augustus II converged outside of Stralsund, to which they later laid siege. For this reason, King Stanisław traveled to Sweden, met with Stenbock in Kristianstad, and went to the Privy Council to ask for reinforcements.[104][105]

The Privy Council agreed to send four infantry regiments of 4,000 men to Stralsund's defense. With the council's approval, Stenbock traveled to Karlskrona in October to assist Wachtmeister with the preparations and execution of the troop transport. The transport fleet sailed on 24 November and a few days later the troops were debarked at Perd on the island of Rügen. Stralsund's commandant, lieutenant general Carl Gustaf Dücker, regarded these reinforcements as less than he had hoped for, since he was informed that the Danes and the Saxons would carry out a major offensive the following year. Stenbock returned to Karlskrona in early December, and at Christmas received a royal order to guard the Swedish west coast, while lieutenant general Gustaf Adam Taube would lead Scania's defense in Stenbock's absence.[106][107]

Order of mobilization[]

In Gothenburg, on 19 May 1712, Stenbock received a new order from Charles XII, this time that he would immediately transport a field army to Pomerania. He was authorized to carry out the transport independently of the Privy Council. He would also submit to King Stanisław Leszczyński and consult with Mauritz Vellingk, who was now governor of Bremen-Verden and commanding general of the Swedish troops in Germany. Stenbock and King Stanisław were to organize the transport in consultation with Wachtmeister and the Admiralty in Karlskrona.[108][109][110]

In mid-June 1712 Stenbock spoke with King Stanisław and the council members Horn and Gyllenstierna in Vadstena, where he presented the financial requirements from Karlskrona for a contribution of 200,000 daler silver coins and 1,500 experienced sailors. Horn and Gyllenstierna were able to obtain only a quarter of the requested amount, citing the Kingdom's general distress and shortage of funds. Stenbock accompanied them to Stockholm and together with Gustaf Cronhielm, Stenbock spoke with the head of the Agency for Public Management to find out about the Kingdom's financial situation. Together they set up a financing proposal that would address the population with appeals for money loans, mainly from the wealthier subjects such as the tradesmen among Stockholm's burghers. Throughout July, Stenbock undertook his borrowing campaign by sending letters to the Swedish governors and magistrates, and holding speeches and banquets in Stockholm. He appealed to the bourgeoisie for money and cargo vessels in order to bring the King back home to Sweden, as well as to improve the badly damaged Swedish foreign trade. In a short time, Stenbock and his helpers collected 400,000 daler silver coins and a loan of nine double-decked bulk carriers. With this contribution, the Swedish high command was able to send decampment orders to the regiments, purchase grain, muster sailors and assemble a transport fleet in Karlskrona at the end of July, while the war fleet was made combat-ready.[111][112][110]

Stenbock left Stockholm and spent a week in Vapnö to say goodbye to his wife and children. In August, Wachtmeister sailed with a fleet of 27 warships from Karlskrona. Stenbock joined the transport fleet at anchor in Karlshamn on 23 August, and set sail for Rügen. The following day, Wachtmeister chased off a Danish fleet led by Admiral Gyldenløve, who retreated to Copenhagen, while Wachtmeister dropped anchor in Køge Bugt.[113][114]

Campaign in Northern Germany[]

On 25 August Stenbock landed at Wittow on the north coast of Rügen and toured for the next few days between Stralsund and various places on Rügen. On 14 September the rest of the transport fleet anchored at Wittow, and two days later, 9,500 men and twenty guns disembarked from the ships. Most of the troops were accommodated on Rügen, while a handful of companies were sent to Stralsund. On the night between 18 and 19 September, the transport fleet that was anchored at Langkenhoff suffered a surprise attack from Gyldenløve's fleet, who bypassed Wachtmeister's battle fleet. Over 50 Swedish transport ships were lost during the attack, half of which were captured by the Danes, and most of the winter storages were lost.[115][116][110]

The loss of the transport fleet was a major logistical loss for Stenbock and the Swedish troops in Germany. Stenbock sent a message to the Privy Council to send a new transport fleet with fresh winter supplies and 4,000 cavalry units that had not yet been transported from Sweden. Meanwhile, Stenbock was ordered by King Stanisław to begin secret negotiations with the Saxon Field Marshal Jacob Heinrich von Flemming to investigate the possibility of a separate peace with King Augustus II. The meeting took place on 11 October in Pütte, eight kilometers west of Stralsund, where Stenbock, together with major generals Georg Reinhold Patkul and Fredrik von Mevius, negotiated with Flemming and his companions, the Russian Master-General of the Ordnance Jacob Bruce and the Danish colonels Bendix Meyer and Poul Vendelbo Løvenørn. Because Flemming rejected King Stanisław's demands regarding Lithuania the negotiations turned out inconclusive. Stenbock held a council of war with his generals and colonels to decide by which route they should march. Since the road to Poland was devastated and blocked by Russian and Saxon troops of between 20,000 and 30,000 men, Stenbock decided to go west to Mecklenburg where the troops would be able to establish reliable supply lines.[117][118]

On 1 November, 16,000 men marched out of Stralsund under Stenbock's direct command. They moved parallel to the enemy lines, which were concentrated south of Stralsund. They crossed the Recknitz river at Damgarten on 4 November, and entered Rostock without a fight ten days later. Stenbock set up headquarters in Schwaan, south of Rostock, and established communications with Wismar. In Mecklenburg, the contribution collection commenced under the command of General War Commissar Peter Malmberg, and the Swedes confiscated significant quantities of food, wagons and horses. At the same time, Danish troops remained around Hamburg and Danish Holstein, while Saxon and Russian troops advanced from the east. On 5 November Stenbock and King Stanisław negotiated with Flemming. Stanisław announced his thoughts on giving up the Polish crown, which created opportunities for an armistice. On 24 November Stenbock was ordered by King Stanisław to discuss a three-month long armistice with the enemy alliance. The negotiations, between Stenbock and major general Carl Gustaf Mellin on one side and Flemming, the Russian commander Prince Alexander Menshikov and Colonels Meyer and Løvenørn on the other, took place a few days later in Lüssow. Stenbock was also given the opportunity to discuss directly with Augustus II, who was not a participant at the talks, but as a guest of the widowed duchess Magdalena Sibylla in Güstrow. The parties agreed upon a two-week ceasefire, starting on 1 December, which allowed the Swedes to collect food reserves undisturbed and gave them more time to assemble a new transport fleet. On 29 November, King Stanisław departed towards Bender to inform Charles XII about the negotiations. Meanwhile, Stenbock remained in Wismar for two weeks due to severe colic attacks. He was informed that a transport fleet under Admiral Gustaf Wattrang had assembled in Karlskrona and tried to sail to Wismar, but due to frequent storms, the fleet failed three times.[119][120][121]

Battle of Gadebusch[]

At the end of the truce, Stenbock was informed that a large Danish army had broken into Mecklenburg from the west and attacked Malmberg's supply troops. To prevent the Danes from joining the other allies, Stenbock decided to prepare his army to march. On 15 December, the Swedes destroyed the bridges across the Warnow river, securing the army's rear and flanks, and the army moved west the following morning. Two days later, they stopped at Karow, where Stenbock was informed that the Danes encamped at Gadebusch and that Saxon cavalry regiments were about to join them. 16,000 Danish troops had set up camp outside Gadebusch's walls under the command of lieutenant general Jobst von Scholten, while King Frederick IV established headquarters in the city's castle. On 18 December Stenbock marched against Gadebusch and divided his army into columns. He camped at the Lütken Brütz mansion, five kilometers east of Gadebusch, on 19 December, where his troops were discovered by Scholten's reconnaissance units after midnight. At daybreak the Danish and Swedish troops prepared for combat.[122][123]

On the morning of 20 December, the Danes took up defensive positions at Wakenstädt, three kilometers south of Gadebusch, in anticipation of a Swedish attack. In the meantime Flemming arrived with Saxon reinforcements. A total of 16,000 Danes and 3,500 Saxons stood before Stenbock's army, which numbered about 14,000. At the advice of the artillery commander Carl Cronstedt, Stenbock let his artillery play an important role in the battle. It was placed in front of the infantry under the protection of one infantry battalion. At 700 meters from the enemy ranks, the Swedish guns bombarded the Danish line; then they were pulled forward with horses and a new bombardment started. At the beginning of the battle, the Swedish cavalry on the right wing managed to surround the Danish cavalry on the left wing. The Danes began to flee backwards, but when they received Saxon reinforcements, the Swedish advance was stopped. The breakthrough left the Danish infantry on the left unprotected. The Swedish infantry advanced in columns and, only when in the immediate vicinity of the enemy, formed a line and opened fire. The Swedish infantry was successful, especially on the right where they penetrated the unprotected Danish cavalry. The Danish infantry sustained heavy losses, but through Saxon reinforcements, the Danish right wing managed to repel the Swedish attacks. The battle faded during dusk and the remaining Danish and Saxon troops withdrew from the battlefield and retreated to Holstein. The Swedish cavalry were too exhausted to pursue them. Danish losses amounted to 2,500 dead and injured, while the Saxon losses were between 700 and 900 killed and injured. In addition, 2,500 Danes and 100 Saxons were taken prisoners. Swedish losses came to 550 killed and 1,000 injured.[124][125][126]

The exhausted Swedish troops were quartered at various locations between Gadebusch and Wismar, while Stenbock went to Wismar with his prisoners and wounded soldiers. Stenbock's victory was celebrated across Sweden, and he received letters of congratulations from the Queen Dowager and Princess of Sweden, Duke Frederick William of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and King Frederick Wilhelm I of Prussia. In addition, King Louis XIV mentioned Stenbock in his New Year's speech before his court in Versailles, and Charles XII ratified Stenbock's appointment as Field Marshal. The letter of appointment was issued in January 1713 and arrived with Stenbock in July the same year.[127][128]

Burning of Altona[]

On 30 December, Stenbock marched across the Trave river into Holstein, in order to support his troops from there. From his headquarters in Schwartau, he sent proclamations regarding contributions to both the Danish and Ducal parts of Holstein, as well as to the Hanseatic City of Lübeck. He sent orders to Governor General Mauritz Vellingk requesting large quantities of clothing for his troops. Vellingk was posted in Hamburg since September 1712, following the occupation of Stade and Bremen-Verden by Danish troops. As Vellingk wanted to avenge the Danes for their destruction of Stade, he advised Stenbock to march into the Danish part of Holstein to destroy the Danish city of Altona on the Elbe river. On 7 January 1713 Stenbock established his headquarters in Pinneberg, north of Hamburg, while Colonels Ulrich Carl von Bassewitz and Johan Carl Strömfelt were sent to Altona with 200 cavalry and 800 dragoon units. On the following morning Stenbock arrived in Altona and arrested the city's provisional bourgeois commission, causing the citizens to negotiate a ransom of 36,000 riksdaler. When Stenbock discussed the matter with Vellingk in Hamburg later that day, the latter argued that Altona must be burned, since the city and its large quantities of food posed a strategic interest for the Allies. Stenbock, however, argued that the city's destruction would cause retaliatory action in Swedish Pomerania and Bremen, and that he had promised the people of Holstein that they could feel safe if they stayed calm and paid contributions. Vellingk warned Stenbock that unless the city was set on fire, he would threaten him with personal responsibility and unpleasant consequences. Stenbock returned to Altona that evening, threatening its citizens that he would burn the city to the ground if they could not give him 100,000 riksdaler before midnight. Even though Bassewitz persuaded Stenbock to reduce the ransom to 50,000 riksdaler, the citizens were unable to collect the sum in such a short time. They panicked and pleaded with Stenbock to spare their lives. Nevertheless, Stenbock left Altona and ordered Strömfelt to burn it down.[129][130][121]

On the night between 8 and 9 January the citizens of Altona were dragged out of their homes by Stromfelt's dragoons, who then ignited the houses. By the morning of 9 January Altona was transformed into a smoldering ghost town, and hundreds of the citizens died in the flames or froze to death. Only a few hundred of the city's 2,000 houses survived the fire. After the destruction, Stenbock sent a letter to government official Ditlev Vibe, stating that he found himself compelled by "justification and an inevitable necessity" to burn down Altona. The Allies sharply criticized Stenbock's action. He received a personal letter from Flemming and Scholten, expressing their disgust at the destruction, and that they could not understand his behavior. Stenbock's act of violence was difficult to defend since Altona's citizens were defenseless and of the same Lutheran-evangelical denomination as the Swedes. He now became a target of anti-Swedish propaganda and a notorious, bloodthirsty arsonist. His actions became widely known as "der Schwedenbrand" (the Swedish Bonfire) or "die Schwedische Einäscherung" (the Swedish Cremation).[131][132]

In mid-January Danish and Saxon troops approached Hamburg, and a Russian army under Tsar Peter I marched from Mecklenburg towards Holstein. On 18 January, Stenbock and his army crossed the Eider Canal, marched into Schleswig and set up camp in Husum. Cavalry divisions under Bassewitz and Strömfelt were sent to Flensburg and Aabenraa. From there, they reported that the northern roads, following heavy rainfalls, were turned into mud and that the villages and farms in the surrounding area were abandoned and emptied of food and valuables. On 22 January, Stenbock held a council of war, where they agreed to occupy the Eiderstedt peninsula and establish food stores under the protection of Holstein-Gottorp's main fortress, Tönning. Following the destruction of Altona Stenbock had entered negotiations with secret envoys from Holstein-Gottorp, which was ruled by Christian August, uncle to the young duke Charles Frederick who at the time stayed at the royal family in Sweden. When the duchy was threatened with destruction by Denmark and its allies, Christian August wanted to use Stenbock's army to defend it. A secret treaty, in which the Swedes were guaranteed Tönning's protection while they in return would ensure the protection of the Duchy during future peace negotiations with Denmark, was signed by Stenbock, Christian August and Geheimräte Henrik Reventlow, Johan Claesson Banér, and Georg Heinrich von Görtz.[133][134]

The allied troops crossed the Eider Canal on 23 January, and a few days later Stenbock's troops clashed with Russian troops at the bridge of Hollingstedt between Husum and the city of Schleswig. Afterwards Stenbock marched to Eiderstedt, spread his troops around the peninsula, and built small redoubts at strategic locations. At the beginning of February, Danish and Saxon troops commenced their attack from Husum while Russian troops advanced across Friedrichstadt and Koldenbüttel. Stenbock retreated towards Tönning and lost several cannons and food stores to the Allies. The Swedish vanguard entered Tönning on 14 February, and were followed by the rest of the infantry, about 2,000 sick soldiers, and the cavalry, who camped on the plains outside the fortress. Stenbock delegated command of the army to major general Georg Reinhold Patkul and Stackelberg, and, together with the cavalry, Stenbock tried to cross the Eider Canal with boats and obtain reinforcements from Sweden. The ship transport failed due to heavy winds, and Tsar Peter moved towards the Swedish bridgehead with 10,000 Russian troops. Stenbock sounded the retreat and half of his cavalry surrendered to the Russians, while the rest slaughtered their horses and escaped back to Tönning.[135][136]

Surrender at Tönning[]

Inside Tönning's walls, 12,000 Swedes were crowded with soldiers and citizens from Holstein, and the fortress suffered from a lack of firewood, food and drinkable water. The Privy Council rejected Stenbock's cries of distress, referring to the Kingdom's critical situation. From the sea, Tönning was blocked by Danish warships, and Stenbock could not expect any help from Charles XII in Bender, since he had been informed by Vellingk that the King had been transferred to Demotika following the skirmish at Bender. The Ottomans could no longer trust Swedish arms when Stenbock, instead of breaking into Poland, chose to negotiate with the enemy. Stenbock began to feel depressed and moody on account of his setbacks, often quarreling with the fortress Commandant Zacharias Wolf, and locked himself in his chamber. He wrote angry letters to the Privy Council and several defensive statements regarding his own actions in the campaign. Afterwards, Stenbock reluctantly held an audience with Baron von Görtz, who said that the fortress only had supplies for three months, that the allied troops had started their advance towards the fortress walls, and suggested that Stenbock consider "an honorable capitulation". When Stenbock's troops entered Tönning, the Danes considered the formerly neutral duchy to be a warring nation. Between 16 and 18 February Danish troops occupied the ducal parts of Schleswig, sent the duchy's troops to Rendsburg as prisoners of war, and replaced the ducal officials with Danish counterparts, while Christian August fled to Hamburg.[137][138]