Ancient history

This article possibly contains original research. (March 2021) |

| Ancient history |

|---|

| Preceded by prehistory |

| Near East |

| Sumer · Kish · Egypt · Elam · Ebla · Akkad · Canaan · Assyria · Babylonia · Qatna · Yamhad · Mitanni · Hittites · Sea Peoples · Anatolia · Israel and Judah · Arabia · Berbers · Phoenicia · Persia |

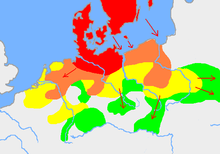

| Europe |

| Minoans · Greece · Illyrians · Argaric · Nuragic · Tartessos · Iberia · Celts · Germanics · Etruscans · Rome · Slavs · Daco-Thracians |

| Horn of Africa |

| Land of Punt · Opone · Macrobia · Kingdom of Dʿmt · Axumite Empire · Mosylon · Sarapion |

| Eurasian Steppe |

| Proto-Indo-Europeans · Afanasievo · Indo-Iranians · Scythia · Tocharians · Huns · Xionites · Turks |

| East Asia |

| China · Japan · Korea · Mongolia |

| South Asia |

| Indus Valley Civilisation · Vedic period · Mahajanapadas · Nanda Empire · Maurya Empire · Satavahana dynasty · Sangam period · Middle Kingdoms |

| Mississippi and Oasisamerica |

| Adena · Hopewell · Mississippian · Puebloans |

| Mesoamerica |

| Olmecs · Epi-Olmec · Zapotec · Mixtec · Maya · Teotihuacan · Toltec Empire |

| Andes |

| Norte Chico · Sechin · Chavín · Paracas · Nazca · Moche · Lima · Tiwanaku · Wari |

| West Africa |

| Dhar Tichitt · Oualata · Nok · Senegambia · Djenné-Djenno · Bantu · Ghana Empire |

| Southeast Asia and Oceania |

| Vietnam · Austronesians · Australia · Polynesia · Funan · Tarumanagara |

| See also |

|

Human history · Ancient maritime history

|

| Followed by Post-classical history |

| Part of a series on | |||

| Human history Human Era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Pleistocene epoch) | |||

| Holocene | |||

|

|||

| Ancient | |||

|

|||

| Postclassical | |||

|

|||

| Modern | |||

|

|||

| ↓ Future | |||

Ancient history is the aggregate of past events[1] from the beginning of writing and recorded human history and extending as far as post-classical history. The phrase may be used either to refer to the period of time or the academic discipline.

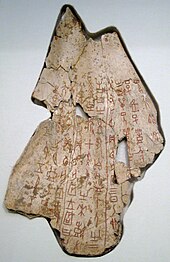

The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script, with the oldest coherent texts from about 2600 BC.[2] Ancient history covers all continents inhabited by humans in the period 3000 BC – AD 500.

The broad term "ancient history" is not to be confused with "classical antiquity". The term classical antiquity is often used to refer to Western history in the Ancient Mediterranean from the beginning of recorded Greek history in 776 BC (first Olympiad). This roughly coincides with the traditional date of the founding of Rome in 753 BC, the beginning of the history of ancient Rome, and the beginning of the Archaic period in Ancient Greece.

The academic term "history" is not to be confused with colloquial references to times past. History is fundamentally the study of the past, and can be either scientific (archaeology, with the examination of physical evidence) or humanistic (the study of history through texts, poetry, and linguistics).

Although the ending date of ancient history is disputed, some Western scholars use the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD (the most used),[3][4] the closure of the Platonic Academy in 529 AD,[5] the death of the emperor Justinian I in 565 AD,[6] the coming of Islam,[7] or the rise of Charlemagne[8] as the end of ancient and Classical European history. Outside of Europe, there have been difficulties with the 450–500 time frame for the transition from ancient to post-classical times.

During the time period of ancient history (starting roughly from 3000 BC), the world population was already exponentially increasing due to the Neolithic Revolution, which was in full progress. According to HYDE estimates from the Netherlands, world population increased exponentially in this period. In 10,000 BC in prehistory, the world population had stood at 2 million, rising to 45 million by 3,000 BC. By the rise of the Iron Age in 1,000 BC, the population had risen to 72 million. By the end of the period in 500 AD, the world population is thought to have stood at 209 million. In 3,500 years, the world population increased by 100 times.[9]

Study[]

Historians have two major ways of understanding the ancient world: archaeology and the study of source texts. Primary sources are those sources closest to the origin of the information or idea under study.[10][11] Primary sources have been distinguished from secondary sources, which often cite, comment on, or build upon primary sources.[12]

Archaeology[]

Archaeology is the excavation and study of artifacts in an effort to interpret and reconstruct past human behavior.[13][14][15][16] Archaeologists excavate the ruins of ancient cities looking for clues as to how the people of the time period lived. Some important discoveries by archaeologists studying ancient history include:

- The Egyptian pyramids:[17] giant tombs built by the ancient Egyptians beginning about 2600 BC as the final resting places of their royalty.

- The study of the ancient cities of Harappa (Pakistan),[18] Mohenjo-daro (Pakistan), and Lothal[19] in India (South Asia).

- The city of Pompeii (Italy):[20] an ancient Roman city preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Its state of preservation is so great that it is a valuable window into Roman culture and provided insight into the cultures of the Etruscans and the Samnites.[21]

- The Terracotta Army:[22] the mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor in ancient China.

- The discovery of Knossos by Minos Kalokairinos and Sir Arthur Evans.

- The discovery of Troy by Heinrich Schliemann.

Source text[]

Most of what is known of the ancient world comes from the accounts of antiquity's own historians. Although it is important to take into account the bias of each ancient author, their accounts are the basis for our understanding of the ancient past. Some of the more notable ancient writers include Herodotus, Thucydides, Arrian, Plutarch, Polybius, Sima Qian, Sallust, Livy, Josephus, Suetonius, and Tacitus.

A fundamental difficulty of studying ancient history is that recorded histories cannot document the entirety of human events, and only a fraction of those documents have survived into the present day.[23] Furthermore, the reliability of the information obtained from these surviving records must be considered.[23][24] Few people were capable of writing histories, as literacy was not widespread in almost any culture until long after the end of ancient history.[25]

The earliest known systematic historical thought emerged in ancient Greece, beginning with Herodotus of Halicarnassus (484–c. 425 BC). Thucydides largely eliminated divine causality in his account of the war between Athens and Sparta,[26] establishing a rationalistic element which set a precedent for subsequent Western historical writings. He was also the first to distinguish between cause and immediate origins of an event.[26]

The Roman Empire was an ancient culture with a relatively high literacy rate,[27] but many works by its most widely read historians are lost. For example, Livy, a Roman historian who lived in the 1st century BC, wrote a history of Rome called Ab Urbe Condita (From the Founding of the City) in 144 volumes; only 35 volumes still exist, although short summaries of most of the rest do exist. Indeed, no more than a minority of the work of any major Roman historian has survived.

Timeline of ancient history[]

(Common Era years in astronomical year numbering)

|

|

This gives a listed timeline, ranging from 3300 BC to 600 AD, that provides an overview of ancient history.

Chronology[]

Prehistory[]

Prehistory is the period before written history. The early human migrations[28] in the Lower Paleolithic saw Homo erectus spread across Eurasia 1.8 million years ago. The controlled use of fire first occurred 800,000 years ago in the Middle Paleolithic. 250,000 years ago, Homo sapiens (modern humans) emerged in Africa. 60–70,000 years ago, some Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa along a coastal route to South and Southeast Asia and reached Australia. 50,000 years ago, modern humans spread from Asia to the Near East. Europe was first reached by modern humans 40,000 years ago. Humans migrated to the Americas about 15,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic.

The 10th millennium BC is the earliest given date for the invention of agriculture and the beginning of the ancient era. Göbekli Tepe was erected by hunter-gatherers in the 10th millennium BC (c. 11,500 years ago), before the advent of sedentism. Together with Nevalı Çori, it has revolutionized understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic. In the 7th millennium BC, Jiahu culture began in China. By the 5th millennium BC, the late Neolithic civilizations saw the invention of the wheel and the spread of proto-writing. In the 4th millennium BC, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the Ukraine-Moldova-Romania region develops. By 3400 BC, "proto-literate" cuneiform is spread in the Middle East.[29] The 30th century BC, referred to as the Early Bronze Age II, saw the beginning of the literate period in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. Around the 27th century BC, the Old Kingdom of Egypt and the First Dynasty of Uruk are founded, according to the earliest reliable regnal eras.

Middle to Late Bronze Age[]

| hideOriginal Civilizations |

|---|

|

The Bronze Age forms part of the three-age system. It follows the Neolithic Age in some areas of the world. In most areas of civilization bronze smelting became a foundation for more advanced societies. There was some contrast with New World societies, who often still preferred stone to metal for utilitarian purposes. Modern historians have identified five original civilizations which emerged in the time period.[30]

- Sumer in the Fertile Crescent

- Indus Valley in Ancient South Asia

- Erlitou in the North China Plain

- Norte Chico in the Andes

- Olmec in Mesoamerica

The first civilization emerged in Sumer in the southern region of Mesopotamia, now part of modern-day Iraq. By 3000 BC, Sumerian city states had collectively formed civilization, with government, religion, division of labor and writing.[31][32] Among the city states Ur was among the most significant.

In the 24th century BC, the Akkadian Empire[33][34] was founded in Mesopotamia. From Sumer, civilization and bronze smelting spread westward to Egypt, the Minoans and the Hittites.

The First Intermediate Period of Egypt of the 22nd century BC was followed by the Middle Kingdom of Egypt between the 21st to 17th centuries BC. The Sumerian Renaissance also developed c. the 21st century BC in Ur. Around the 18th century BC, the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt began. Egypt was a superpower at the time. By 1600 BC, Mycenaean Greece developed and invaded the remains of Minoan civilization. The beginning of Hittite dominance of the Eastern Mediterranean region is also seen in the 1600s BC. The time from the 16th to the 11th centuries BC around the Nile is called the New Kingdom of Egypt. Between 1550 BC and 1292 BC, the Amarna Period developed in Egypt.

East of the Iranian world, was the Indus River Valley civilization which organized cities neatly on grid patterns.[35] However the Indus River Valley civilization diminished after 1900 BC and was later replaced with Indo-Aryan peoples who established Vedic culture.

The beginning of the Shang dynasty emerged in China in this period, and there was evidence of a fully developed Chinese writing system. The Shang Dynasty is the first Chinese regime recognized by western scholars though Chinese historians insist that the Xia dynasty preceded it. The Shang dynasty practiced forced labor to complete public projects. There is evidence of massive ritual burial.

Across the ocean, the earliest known civilization of the Americas appeared in the river valleys of the desert coast of central modern day Peru. The Norte Chico civilization's first city flourished around 3100 BC. The Olmecs are supposed to appear later in Mesoamerica between the 14th and 13th centuries.

Early Iron Age[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

The Iron Age is the last principal period in the three-age system, preceded by the Bronze Age. Its date and context vary depending on the country or geographical region. The Iron Age over all was characterized by the prevalent smelting of iron with ferrous metallurgy and the use of carbon steel. Smelted iron proved more durable than earlier metals such as copper or bronze and allowed for more productive societies. The Iron Age took place at different times in different parts of the world, and comes to an end when a society began to maintain historical records.

During the 13th to 12th centuries BC, the Ramesside Period occurred in Egypt. Around 1200 BC, the Trojan War was thought to have taken place.[36] By around 1180 BC, the disintegration of the Hittite Empire was under way. The collapse of the Hitties was part of the larger scale Bronze Age Collapse which took place in the ancient Near East around 1200 BC. In Greece the Mycenae and Minona both disintegrated. A wave of Sea Peoples attacked many countries, only Egypt survived intact. Afterwards some entirely new successor civilizations arose in the Eastern Mediterranean.

In 1046 BC, the Zhou force, led by King Wu of Zhou, overthrew the last king of the Shang dynasty. The Zhou dynasty was established in China shortly thereafter. During this Zhou era China embraced a feudal society of decentralized power. Iron Age China then dissolved into the warring states period where possibly millions of soldiers fought each other over feudal struggles.

Pirak is an early iron-age site in Balochistan, Pakistan, going back to about 1200 BC. This period is believed to be the beginning of the Iron Age in India and the subcontinent.[37] Around the same time came the Vedas, the oldest sacred texts for the Hindu religion.

In 1000 BC, the Mannaean Kingdom began in Western Asia. Around the 10th to 7th centuries BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire developed in Mesopotamia.[38] In 800 BC, the rise of Greek city-states began. In 776 BC, the first recorded Olympic Games were held.[39] In contrast to neighboring cultures the Greek City states did not become a single militaristic empire but competed with each other as separate polis.

Axial Age[]

The preceding Iron Age is often thought to have ended in the Middle East around 550 BC due to the rise of historiography (the historical record). The Axial Age is used to describe history between 800 and 200 BC of Eurasia, including ancient Greece, Iran, India and China. Widespread trade and communication between distinct regions in this period, including the rise of the Silk Road. This period saw the rise of philosophy and proselytizing religions.

Philosophy, religion and science were diverse in the Hundred Schools of Thought producing thinkers such as Confucius, Lao Tzu and Mozi during the 6th century BC. Similar trends emerged throughout Eurasia in India with the rise of Buddhism, in the Near East with Zoroastrianism and Judaism and in the west with ancient Greek philosophy. In these developments religious and philosophical figures were all searching for human meaning.[40]

The Axial Age and its aftermath saw large wars and the formation of large empires that stretched beyond the limits of earlier Iron Age Societies. Significant for the time was the Persian Achaemenid Empire.[41] The empire's vast territory extended from modern day Egypt to Xinjiang. The empire's legacy include the rise of commerce over land routes through Eurasia as well as the spreading of Persian culture through the middle east. The Royal Road allowed for efficient trade and taxation. Though Macedonian Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire in its entirety, the unity of Alexander's conquests did not survive past his lifetime. Greek culture, and technology spread through West and South Asia often synthesizing with local cultures.

Formation of empires and fragmentation[]

Separate Greek kingdoms Egypt and Asia encouraged trade and communication like earlier Persian administrations.[42] Combined with the expansion of the Han dynasty westward the Silk Road as a series of routes made possible the exchange of goods between the Mediterranean Basin, South Asia and East Asia. In South Asia, the Mauryan empire briefly annexed much of the Indian Subcontinent though short lived, its reign had the legacies of spreading Buddhism and providing an inspiration to later Indian states.

Supplanting the warring Greek kingdoms in the western world came the growing Roman Republic and the Iranian Parthian Empire. As a result of empires, urbanization and literacy spread to locations which had previously been at the periphery of civilization as known by the large empires. Upon the turn of the millennium the independence of tribal peoples and smaller kingdoms were threatened by more advanced states. Empires were not just remarkable for their territorial size but for their administration and the dissemination of culture and trade, in this way the influence of empires often extended far beyond their national boundaries. Trade routes expanded by land and sea and allowed for flow of goods between distant regions even in the absence of communication. Distant nations such as Imperial Rome and the Chinese Han Dynasty rarely communicated but trade of goods did occur as evidenced by archaeological discoveries such as Roman coins in Vietnam. At this time most of the world's population inhabited only a small part of the earth's surface. Outside of civilization large geographic areas such as Siberia, Sub Saharan Africa and Australia remained sparsely populated. The New World hosted a variety of separate civilizations but its own trade networks were smaller due to the lack of draft animals and the wheel.

Empires with their immense military strength remained fragile to civil wars, economic decline and a changing political environment internationally. In 220 AD Han China collapsed into warring states while the European Roman Empire began to suffer from turmoil in the 3rd-century crisis. In Persia regime change took place from Parthian Empire to the more centralized Sassanian Empire. The land based Silk Road continued to deliver profits in trade but came under continual assault by nomads all on the northern frontiers of Eurasian nations. Safer sea routes began to gain preference in the early centuries AD

Proselytizing religions began to replace polytheism and folk religions in many areas. Christianity gained a wide following in the Roman Empire, Zoroastrianism became the state enforced religion of Iran and Buddhism spread to East Asia from South Asia. Social change, political transformation as well as ecological events all contributed to the end of ancient times and the beginning of the Post Classical era in Eurasia roughly around the year 500.

Developments[]

Religion and philosophy[]

The rise of civilization corresponded with the institutional sponsorship of belief in gods, supernatural forces and the afterlife. During the Bronze Age, many civilizations adopted their own form of Polytheism. Usually, polytheistic Gods manifested human personalities, strengths and failings. Early religion was often based on location, with cities or entire countries selecting a deity, that would grant them preferences and advantages over their competitors. Worship involved the construction of representation of deities, and the granting of sacrifices. Sacrifices could be material goods, food, or in extreme cases human sacrifice to please a deity. New philosophies and religions arose in both east and west, particularly about the 6th century BC. Over time, a great variety of religions developed around the world, with some of the earliest major ones being Hinduism (around 2000 BC), Buddhism (5th century BC), and Jainism (6th century BC) in India, and Zoroastrianism in Persia. The Abrahamic religions trace their origin to Judaism, around 1700 BC.

The ancient Indian philosophy is a fusion of two ancient traditions: Sramana tradition and Vedic tradition. Indian philosophy begins with the Vedas where questions related to laws of nature, the origin of the universe and the place of man in it are asked. Jainism and Buddhism are continuation of the Sramana school of thought. The Sramanas cultivated a pessimistic world view of the samsara as full of suffering and advocated renunciation and austerities. They laid stress on philosophical concepts like Ahimsa, Karma, Jnana, Samsara and Moksa. While there are ancient relations between the Indian Vedas and the Iranian Avesta, the two main families of the Indo-Iranian philosophical traditions were characterized by fundamental differences in their implications for the human being's position in society and their view on the role of man in the universe.

In the east, three schools of thought were to dominate Chinese thinking until the modern day. These were Taoism, Legalism and Confucianism. The Confucian tradition, which would attain dominance, looked for political morality not to the force of law but to the power and example of tradition. Confucianism would later spread into the Korean peninsula and Goguryeo[43] and toward Japan.

In the west, the Greek philosophical tradition, represented by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, was diffused throughout Europe and the Middle East in the 4th century BC by the conquests of Alexander III of Macedon, more commonly known as Alexander the Great. After the Bronze and Iron Age religions formed, the rise and spread of Christianity through the Roman world marked the end of Hellenistic philosophy and ushered in the beginnings of Medieval philosophy.

Science and technology[]

|

|

In the history of technology and ancient science during the growth of the ancient civilizations, ancient technological advances were produced in engineering. These advances stimulated other societies to adopt new ways of living and governance. Sometimes, technological development was sponsored by the state.[44]

The characteristics of Ancient Egyptian technology are indicated by a set of artifacts and customs that lasted for thousands of years. The Egyptians invented and used many basic machines, such as the ramp and the lever, to aid construction processes. The Egyptians also played an important role in developing Mediterranean maritime technology including ships[45] and lighthouses.[46]

Water managing Qanats which likely emerged on the Iranian plateau and possibly also in the Arabian peninsula sometime in the early 1st millennium BC spread from there slowly west- and eastward.[47]

The history of science and technology in India dates back to ancient times. The Indus Valley civilization yields evidence of hydrography, and sewage collection and disposal being practiced by its inhabitants. Among the fields of science and technology pursued in India were metallurgy, astronomy, mathematics and Ayurveda. Some ancient inventions include plastic surgery, cataract surgery, Hindu-Arabic numeral system and Wootz steel. The history of science and technology in China show significant advances in science, technology, mathematics, and astronomy. The first recorded observations of comets and supernovae were made in China. Traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture and herbal medicine were also practiced.[citation needed]

Ancient Greek technology developed at an unprecedented speed during the 5th century BC, continuing up to and including the Roman period, and beyond. Inventions that are credited to the ancient Greeks such as the gear, screw, bronze casting techniques, water clock, water organ, torsion catapult and the use of steam to operate some experimental machines and toys. Many of these inventions occurred late in the Greek period, often inspired by the need to improve weapons and tactics in war. Roman technology is the engineering practice which supported Roman civilization and made the expansion of Roman commerce and Roman military possible over nearly a thousand years. The Roman Empire had the most advanced set of technology of their time, some of which may have been lost during the turbulent eras of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Roman technological feats of many different areas, like civil engineering, construction materials, transport technology, and some inventions such as the mechanical reaper went unmatched until the 19th century.[citation needed]

Maritime activity[]

The history of ancient navigation began in earnest when men took to the sea in planked boats and ships propelled by sails hung on masts, like the Ancient Egyptian Khufu ship from the mid-3rd millennium BC. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Necho II sent out an expedition of Phoenicians, which in three years sailed from the Red Sea around Africa to the mouth of the Nile.[48] Many current historians tend to believe Herodotus on this point, even though Herodotus himself was in disbelief that the Phoenicians had accomplished the act.

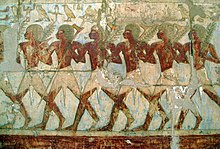

Hannu was an ancient Egyptian explorer (around 2750 BC) and the first explorer of whom there is any knowledge. He made the first recorded exploring expedition, writing his account of his exploration in stone. Hannu travelled along the Red Sea to Punt, and sailed to what is now part of eastern Ethiopia and Somalia. He returned to Egypt with great treasures, including precious myrrh, metal and wood.

Warfare[]

Ancient warfare is war as conducted from the beginnings of recorded history to the end of the ancient period. In Europe, the end of antiquity is often equated with the fall of Rome in 476. In China, it can also be seen as ending in the 5th century, with the growing role of mounted warriors needed to counter the ever-growing threat from the north.

The difference between prehistoric warfare and ancient warfare is less one of technology than of organization. The development of the first city-states, and then empires, allowed warfare to change dramatically. Beginning in Mesopotamia, states produced sufficient agricultural surplus that full-time ruling elites and military commanders could emerge. While the bulk of military forces were still farmers, the society could support having them campaigning rather than working the land for a portion of each year. Thus, organized armies developed for the first time.

These new armies could help states grow in size and became increasingly centralized, and the first empire, that of the Sumerians, formed in Mesopotamia. Early ancient armies continued to primarily use bows and spears, the same weapons that had been developed in prehistoric times for hunting. Early armies in Egypt and China followed a similar pattern of using massed infantry armed with bows and spears.

Artwork and music[]

| Ancient art history |

|---|

| Middle East |

|

| Asia |

|

| European prehistory |

| Classical art |

|

Ancient music is music that developed in literate cultures, replacing prehistoric music. Ancient music refers to the various musical systems that were developed across various geographical regions such as Persia, India, China, Greece, Rome, Egypt and Mesopotamia (see music of Mesopotamia, music of ancient Greece, music of ancient Rome, music of Iran). Ancient music is designated by the characterization of the basic audible tones and scales. It may have been transmitted through oral or written systems. Arts of the ancient world refers to the many types of art that were in the cultures of ancient societies, such as those of ancient China, Egypt, Greece, India, Persia, Mesopotamia and Rome.

Timelines[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2018) |

Comparative timeline[]

Comparison table[]

| Name | Period | Area | Occupations | Writing | Religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesopotamia | 3300–750 BC | Sumer, Babylonia, Assyric Highlands | Dairy farming, metal working, potter's wheel, sexagesimal system, textiles | Cuneiform | Polytheistic |

| Andean civilizations | 3200–1700 BC Norte Chico, 900–200 BC Chavin, 100–800 AD Nazca culture | Peru, Ecuador, Colombia | Maritime origins, Nazca Lines, quipu, unique system of government | None | Polytheistic |

| Ancient India | 3300–500 BC | South Asia | Agriculture, astrology, astronomy, city planning, dams, literature, martial arts, mathematics, medicine, potter's wheel, temple builders | Pictographic, Brahmi script | Hinduism |

| Egyptian | 3000–30 BC | North Eastern Africa along River Nile | Decimal system, Egyptian pyramids, mummification, solar calendar | Hieroglyphic | Ancient Egyptian religion |

| Nubian | 3000–350 BC | North Eastern Africa along the Nile | , Nubian pyramids, pottery, solar calendar | Hieroglyphic | Ancient Egyptian religion |

| Greek | 2700–1500 BC (Cycladic and Minoan civilization), 1600–1100 BC (Mycenaean Greece), 800–100 BC (Ancient Greece) | Greece (Peloponnese, Epirus, Central Greece, Macedon), later Alexandria | Agriculture, architecture, astronomy, chemistry, drama, history, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, physics, poetry, political science, rhetoric, warfare, winemaking | Greek | Ancient Greek religion |

| Chinese | 1600–221 BC Ancient China; 221 BC – 581 AD Early Imperial China | China | Chinaware, Great Wall of China, metals, paper, pottery, silk | Chinese | Chinese folk religion, Confucianism |

| Mesoamerica | 1500–400 BC – Olmecs, 250–900 AD Maya | Southern Mexico, Guatemala | Agriculture, Bloodletting, Mesoamerican calendars, Olmec colossal heads, popcorn, textiles | Cascajal Block, Maya | Mesoamerican religion |

| Iranian | 730 BC – 640 AD | Greater Iran | Agriculture, architecture, landscaping, postal service | Cuneiform, Pahlavi | Zoroastrianism |

| Roman | 600 BC – 600 AD | Italy, spread across Europe and North Africa | Agriculture, Roman calendar, concrete | Latin | Religion in ancient Rome |

Historical ages[]

History by region[]

Southwest Asia (Near East)[]

The ancient Near East is considered the cradle of civilization. It was the first to practice intensive year-round agriculture; created the first coherent writing system, invented the potter's wheel and then the vehicular- and mill wheel, created the first centralized governments, law codes and empires, as well as introducing social stratification, slavery and organized warfare, and it laid the foundation for the fields of astronomy and mathematics.

Mesopotamia[]

Mesopotamia is the site of some of the earliest known civilizations in the world. Early settlement of the alluvial plain lasted from the Ubaid period (late 6th millennium BC) through the Uruk period (4th millennium BC) and the Dynastic periods (3rd millennium BC) until the rise of Babylon in the early 2nd millennium BC. The surplus of storable foodstuffs created by this economy allowed the population to settle in one place instead of migrating after crops and herds. It also allowed for a much greater population density, and in turn required an extensive labor force and division of labor. This organization led to the necessity of record keeping and the development of writing (c. 3500 BC).

Babylonia was an Amorite state in lower Mesopotamia (modern southern Iraq), with Babylon as its capital. Babylonia emerged when Hammurabi (fl. c. 1728–1686 BC, according to the short chronology) created an empire out of the territories of the former kingdoms of Sumer and Akkad. The Amorites being ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, Babylonia adopted the written Akkadian language for official use; they retained the Sumerian language for religious use, which by that time was no longer a spoken language. The Akkadian and Sumerian cultures played a major role in later Babylonian culture, and the region would remain an important cultural center, even under outside rule. The earliest mention of the city of Babylon can be found in a tablet from the reign of Sargon of Akkad, dating back to the 23rd century BC.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire, or Chaldea, was Babylonia under the rule of the 11th ("Chaldean") dynasty, from the revolt of Nabopolassar in 626 BC until the invasion of Cyrus the Great in 539 BC. Notably, it included the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, who conquered the Kingdom of Judah and Jerusalem.

Akkad was a city and its surrounding region in central Mesopotamia. Akkad also became the capital of the Akkadian Empire.[49] The city was probably situated on the west bank of the Euphrates, between Sippar and Kish (in present-day Iraq, about 50 km (31 mi) southwest of the center of Baghdad). Despite an extensive search, the precise site has never been found. Akkad reached the height of its power between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC, following the conquests of King Sargon of Akkad. Because of the policies of the Akkadian Empire toward linguistic assimilation, Akkad also gave its name to the predominant Semitic dialect: the Akkadian language, reflecting use of akkadû ("in the language of Akkad") in the Old Babylonian period to denote the Semitic version of a Sumerian text.

Assyria was originally (in the Middle Bronze Age) a region on the Upper Tigris, named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur. Later, as a nation and empire that came to control all of the Fertile Crescent, Egypt and much of Anatolia, the term "Assyria proper" referred to roughly the northern half of Mesopotamia (the southern half being Babylonia), with Nineveh as its capital. The Assyrian kings controlled a large kingdom at three different times in history. These are called the Old (20th to 15th centuries BC), Middle (15th to 10th centuries BC), and Neo-Assyrian (911–612 BC) kingdoms, or periods, of which the last is the most well known and best documented. Assyrians invented excavation to undermine city walls, battering rams to knock down gates, as well as the concept of a corps of engineers, who bridged rivers with pontoons or provided soldiers with inflatable skins for swimming.[50]

Mitanni was an Indo-Iranian[51] empire in northern Mesopotamia from c. 1500 BC. At the height of Mitanni power, during the 14th century BC, it encompassed what is today southeastern Turkey, northern Syria and northern Iraq, centered around its capital, Washukanni, whose precise location has not been determined by archaeologists.

Iranian people[]

Elam is the name of an ancient civilization located in what is now southwest Iran. Archaeological evidence associated with Elam has been dated to before 5000 BC.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58] According to available written records, it is known to have existed from around 3200 BC – making it among the world's oldest historical civilizations – and to have endured up until 539 BC. Its culture played a crucial role in the Gutian Empire, especially during the Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded it, when the Elamite language remained among those in official use. The Elamite period is considered a starting point for the history of Iran.

The Medes were an ancient Iranian people. They had established their own empire by the 6th century BC, having defeated the Neo-Assyrian Empire with the Chaldeans. They overthrew Urartu later on as well. The Medes are credited with the foundation of the first Iranian empire, the largest of its day until Cyrus the Great established a unified Iranian empire of the Medes and Persian, often referred to as the Achaemenid Empire, by defeating his grandfather and overlord, Astyages the king of Media.

The Achaemenid Empire was the largest and most significant of the Persian Empires, and followed the Median Empire as the second great empire of the Iranians. It is noted in western history as the foe of the Greek city states in the Greco-Persian Wars, for freeing the Israelites from their Babylonian captivity, for its successful model of a centralized bureaucratic administration, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus (one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World), and for instituting Aramaic as the empire's official language. Because of the Empire's vast extent and long endurance, Persian influence upon the language, religion, architecture, philosophy, law and government of nations around the world lasts to this day. At the height of its power, the Achaemenid dynasty encompassed approximately 8.0 million square kilometers, held the greatest percentage of world population to date, stretched three continents (Europe, Asia and Africa) and was territorially the largest empire of classical antiquity.

Parthia was an Iranian civilization situated in the northeastern part of modern Iran. Their power was based on a combination of the guerrilla warfare of a mounted nomadic tribe, with organizational skills to build and administer a vast empire – even though it never matched in power and extent the Persian empires that preceded and followed it. The Parthian Empire was led by the Arsacid dynasty, which reunited and ruled over significant portions of the Near East and beyond, after defeating and disposing the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, beginning in the late 3rd century BC. It was the third native dynasty of ancient Iran (after the Median and the Achaemenid dynasties). Parthia had many wars with the Roman Republic (and subsequently the Roman Empire), which marked the start of what would be over 700 years of frequent Roman-Persian Wars.

The Sassanid Empire, lasting the length of the Late Antiquity period, is considered to be one of Iran's most important and influential historical periods. In many ways the Sassanid period witnessed the highest achievements of Persian civilization and constituted the last great Iranian Empire before the Muslim conquest and the adoption of Islam.[59] During Sassanid times, Persia influenced Roman civilization considerably,[60] and the Romans reserved for the Sassanid Persians alone the status of equals. Sassanid cultural influence extended far beyond the empire's territorial borders, reaching as far as Western Europe,[61] China, and India, playing a role, for example, in the formation of both European and Asiatic medieval art.[62]

Armenia[]

The early history of the Hittite empire is known through tablets that may first have been written in the 17th century BC but survived only as copies made in the 14th and 13th centuries BC. These tablets, known collectively as the Anitta text,[63] begin by telling how Pithana the king of Kussara or Kussar (a small city-state yet to be identified by archaeologists) conquered the neighbouring city of Neša (Kanesh). However, the real subject of these tablets is Pithana's son Anitta, who conquered several neighbouring cities, including Hattusa and Zalpuwa (Zalpa).

Assyrian inscriptions of Shalmaneser I (c. 1270 BC) first mention Uruartri as one of the states of Nairi – a loose confederation of small kingdoms and tribal states in the Armenian Highland from the 13th to 11th centuries BC. Uruartri itself was in the region around Lake Van. The Nairi states were repeatedly subjected to attacks by the Assyrians, especially under Tukulti-Ninurta I (c. 1240 BC), Tiglath-Pileser I (c. 1100 BC), Ashur-bel-kala (c. 1070 BC), Adad-nirari II (c. 900), Tukulti-Ninurta II (c. 890), and Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC).

The Kingdom of Armenia was an independent kingdom from 321 BC to 428 AD, and a client state of the Roman and Persian empires until 428. Between 95 and 55 BC under the rule of King Tigranes the Great, the Kingdom of Armenia became a large and powerful empire stretching from the Caspian to the Mediterranean Seas. During this short time it was considered to be the most powerful state in the Roman East.[64][65]

Israel[]

Israel and Judah were related Iron Age kingdoms of the ancient Levant and had existed during the Iron Ages and the Neo-Babylonian, Persian and Hellenistic periods. The name Israel first appears in the stele of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah c. 1209 BC, "Israel is laid waste and his seed is no more."[66] This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity of the central highlands, well enough established to be perceived by the Egyptians as a possible challenge to their hegemony, but an ethnic group rather than an organised state;[67] Archaeologist Paula McNutt says: "It is probably ... during Iron Age I [that] a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'," differentiating itself from its neighbours via prohibitions on intermarriage, an emphasis on family history and genealogy, and religion.[68]

Israel had emerged by the middle of the 9th century BC, when the Assyrian King Shalmaneser III names "Ahab the Israelite" among his enemies at the battle of Qarqar (853). Judah emerged somewhat later than Israel, probably during the 9th century BC, but the subject is one of considerable controversy.[69] Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding neo-Assyrian empire, which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722). A series of campaigns by the Neo-Babylonian Empire between 597 and 582 led to the destruction of Judah.

Followed by the fall of Babylon to the Persian empire, Jews were allowed, by Cyrus the Great, to return to Judea. The Hasmonean Kingdom (followed by the Maccabean revolt) had existed during the Hellenistic period and then the Herodian kingdom during the Roman period.

Others[]

The history of Pre-Islamic Arabia before the rise of Islam in the 630s is not known in great detail. Archaeological exploration in the Arabian peninsula has been sparse; indigenous written sources are limited to the many inscriptions and coins from southern Arabia. Existing material consists primarily of written sources from other traditions (such as Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, Romans, etc.) and oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Many small kingdoms prospered from Red sea and Indian Ocean trade. Major kingdoms included the Sabaeans, Awsan, Lahkimid Himyar and the Nabateans. Arab kingdoms are occasionally mentioned in the Hebrew Old Testament under the name of Edom. Though the Ugaritic site is thought to have been inhabited earlier, Neolithic Ugarit was already important enough to be fortified with a wall early on. The first written evidence mentioning the city comes from the nearby city of Ebla, c. 1800 BC. Ugarit passed into the sphere of influence of Egypt, which deeply influenced its art. On the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Israel, Palestine and Lebanon, Canaanite peoples became wealth through trade inspiring Phoenicians.

Phoenicia was an ancient civilization centered in the north of ancient Canaan, with its heartland along the coastal regions of modern-day Lebanon, Syria and Israel. Phoenician civilization was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean between the period of 1550 to 300 BC. One Phoenician colony, Carthage, became a powerful nation in its own right.

Afro-Asiatic Africa[]

Carthage[]

Carthage was founded in 814 BC by Phoenician settlers from the city of Tyre, bringing with them the city-god Melqart.[70] Ancient Carthage was an informal hegemony of Phoenician city-states throughout North Africa and modern Spain from 575 BC until 146 BC. It was more or less under the control of the city-state of Carthage after the fall of Tyre to Babylonian forces. At the height of the city's influence, its empire included most of the western Mediterranean. The empire was in a constant state of struggle with the Roman Republic, which led to a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars. After the third and final Punic War, Carthage was destroyed then occupied by Roman forces. Nearly all of the territory held by Carthage fell into Roman hands.

Egypt[]

Ancient Egypt was a long-lived civilization geographically located in north-eastern Africa. It was concentrated along the middle to lower reaches of the Nile River reaching its greatest extension during the 2nd millennium BC, which is referred to as the New Kingdom period. It reached broadly from the Nile Delta in the north, as far south as Jebel Barkal at the Fourth Cataract of the Nile. Extensions to the geographical range of ancient Egyptian civilization included, at different times, areas of the southern Levant, the Eastern Desert and the Red Sea coastline, the Sinai Peninsula and the Western Desert (focused on the several oases).

Ancient Egypt developed over at least three and a half millennia. It began with the incipient unification of Nile Valley polities around 3500 BC and is conventionally thought to have ended in 30 BC when the early Roman Empire conquered and absorbed Ptolemaic Egypt as a province. (Though this last did not represent the first period of foreign domination, the Roman period was to witness a marked, if gradual transformation in the political and religious life of the Nile Valley, effectively marking the termination of independent civilisational development).

The civilization of ancient Egypt was based on a finely balanced control of natural and human resources, characterised primarily by controlled irrigation of the fertile Nile Valley; the mineral exploitation of the valley and surrounding desert regions; the early development of an independent writing system and literature; the organisation of collective projects; trade with surrounding regions in east / central Africa and the eastern Mediterranean; finally, military ventures that exhibited strong characteristics of imperial hegemony and territorial domination of neighbouring cultures at different periods. Motivating and organizing these activities were a socio-political and economic elite that achieved social consensus by means of an elaborate system of religious belief under the figure of a (semi)-divine ruler (usually male) from a succession of ruling dynasties and which related to the larger world by means of polytheistic beliefs.

Nubia[]

The Kushite civilization, which is also known as Nubia, was formed before a period of Egyptian incursion into the area. The first cultures arose in what is now Sudan before the time of a unified Egypt, and the most widespread culture is known as the Kerma civilization. Egyptians referred to Nubia as "Ta-Seti," or "The Land of the Bow," since the Nubians were known to be expert archers. The two civilization shared an abundance of peaceful cultural interchange and cooperation, including mixed marriages and even the same gods. In the New Kingdom, Nubians became indistinguishable in the archaeological record from Egyptians. The Kingdom of Kush survived longer than that of Egypt and at its greatest extent Nubia ruled over Egypt (under the leadership of King Piye), and controlled Egypt during the 8th century BC as the 25th Dynasty.[71]

It is also referred to as Ethiopia in ancient Greek and Roman records. According to Josephus and other classical writers, the Kushite Empire covered all of Africa, and some parts of Asia and Europe at one time or another. In contrast to the Egyptians the Nubians had an unusually high number of ruling queens also known as Kandake, especially during the golden age of the Meroitic Kingdom. Unlike the rest of the world at the time, women in Nubia exercised significant control in society.[72] The Kushites are also famous for having buried their monarchs along with all their courtiers in mass graves. The Kushites also built burial mounds and pyramids, and shared some of the same gods worshipped in Egypt, especially Amon and Isis.

Land of Punt[]

The Land of Punt, also called Pwenet or Pwene[73] by the ancient Egyptians, was a trading partner known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, African blackwood, ebony, ivory, slaves and wild animals.[73] Information about Punt has been found in ancient Egyptian records of trade missions to this region. The exact location of Punt remains a mystery. The mainstream view is that Punt was located to the south-east of Egypt, most likely on the coast of the Horn of Africa. Archaeologist Richard Pankhurst (academic) states;

"[Punt] has been identified with territory on both the Arabian and the Horn of Africa coasts. Consideration of the articles that the Egyptians obtained from Punt, notably gold and ivory, suggests, however, that these were primarily of African origin. ... This leads us to suppose that the term Punt probably applied more to African than Arabian territory."[73][74][75][76]

The earliest recorded Egyptian expedition to Punt was organized by Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty (25th century BC) although gold from Punt is recorded as having been in Egypt in the time of King Khufu of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt.[77] Subsequently, there were more expeditions to Punt in the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Eleventh dynasty of Egypt, the Twelfth dynasty of Egypt and the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt. In the Twelfth dynasty of Egypt, trade with Punt was celebrated in popular literature in "Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor".

Axum and Ancient Ethiopia[]

The Axumite Empire was an important trading nation in northeastern Africa centered in present-day Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, it existed from approximately 100–940 AD, growing from the Iron Age proto-Aksumite period c. 4th century BC to achieve prominence by the 1st century AD.[78] According to the Book of Aksum, Aksum's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush.[79] The capital was later moved to Axum in northern Ethiopia. The kingdom used the name "Ethiopia" as early as the 4th century.[80][81]

The Empire of Aksum at its height at its climax by the early 6th century extended through much of modern Ethiopia and across the Red Sea to Arabia. The capital city of the empire was Aksum, now in northern Ethiopia.

Its ancient capital is found in northern Ethiopia, the kingdom used the name "Ethiopia" as early as the 4th century.[80][82] Aksum is mentioned in the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as an important market place for ivory, which was exported throughout the ancient world, and states that the ruler of Aksum in the 1st century AD was Zoscales, who, besides ruling in Aksum also controlled two harbours on the Red Sea: Adulis (near Massawa) and Avalites (Assab). He is also said to have been familiar with Greek literature.[83] It is also an alleged resting place of the Ark of the Covenant and home of the Queen of Sheba. Aksum was also one of the first major empires to convert to Christianity.

Macrobia and the Barbaroi City States[]

Macrobia was an ancient kingdom situated in the Horn of Africa (present day Somalia) it is mentioned in the 5th century BC. According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor Cambyses II upon his conquest of Egypt (525 BC) sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based at least in part on stature, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to string it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire .[84][85][86]

The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.[87]

After the collapse of Macrobia, several wealthy ancient city-states, such as Opone, Essina, Sarapion, Nikon, Malao, Damo and Mosylon near Cape Guardafui would emerge from the 1st millennium BC–500 AD to compete with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman trade and flourished along the Somali coast. They developed a lucrative trading network under a region collectively known in the Peripilus of the Erythraean Sea as Barbaria[88]

Niger-Congo Africa[]

Nok culture[]

The Nok culture appeared in Nigeria around 1000 BC and mysteriously vanished around 200 AD. The civilization's social system is thought to have been highly advanced. The Nok civilization was considered to be the earliest sub-Saharan producer of life-sized Terracotta which have been discovered by archaeologists. The Nok also used iron smelting that may have been independently developed.[89] A Nok sculpture resident at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, portrays a sitting dignitary wearing a "Shepherds Crook" on the right arm, and a "hinged flail" on the left. These are symbols of authority associated with ancient Egyptian pharaohs, and the god Osiris, which suggests that an ancient Egyptian style of social structure, and perhaps religion, existed in the area of modern Nigeria during the late Pharonic period.[90] (Informational excerpt copied from Nigeria and Nok culture articles)

The Sahel[]

Djenné-Djenno[]

The civilization of Djenné-Djenno was located in the Niger River Valley in the country of Mali and is considered to be among the oldest urbanized centers and the best-known archaeology site in Sub-Saharan Africa. This archaeological site is located about 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) away from the modern town and is believed to have been involved in long-distance trade and possibly the domestication of African rice. The site is believed to exceed 33 hectares (82 acres); however, this is yet to be confirmed with extensive survey work. With the help of archaeological excavations mainly by Susan and Roderick McIntosh, the site is known to have been occupied from 250 BC to 900 AD The city is believed to have been abandoned and moved where the current city is located due to the spread of Islam and the building of the Great Mosque of Djenné. Previously, it was assumed that advanced trade networks and complex societies did not exist in the region until the arrival of traders from Southwest Asia. However, sites such as Djenné-Djenno disprove this, as these traditions in West Africa flourished long before. Towns similar to that at Djenne-Jeno also developed at the site of Dia, also in Mali along the Niger River, from around 900 BC.

Dhar Tichitt& Oulata[]

Dhar Tichitt and Oualata were prominent among the early urban centres, dated to 2000 BC, in present-day Mauritania. About 500 stone settlements littered the region in the former savannah of the Sahara. Its inhabitants fished and grew millet. It has been found that the Soninke of the Mandé peoples were responsible for constructing such settlements. Around 300 BC, the region became more desiccated and the settlements began to decline, most likely relocating to Koumbi Saleh. From the type of architecture and pottery, it is believed that Tichit was related to the subsequent Ghana Empire. Old Jenne (Djenne) began to be settled around 300 BC, producing iron and with sizeable population, evidenced in crowded cemeteries. The inhabitants and creators of these settlements during these periods thought to have been ancestors of the Soninke people.

South Asia[]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

One of the earliest Neolithic sites in the Indian subcontinent is Bhirrana along the ancient Ghaggar-Hakra (Saraswati) riverine system in the present day state of Haryana in India, dating to around 7600 BC.[91] Other early sites include Lahuradewa in the Middle Ganges region and Jhusi near the confluence of Ganges and Yamuna rivers, both dating to around 7000 BC.[92][93] The aceramic Neolithic at Mehrgarh lasts from 7000 to 5500 BC, with the ceramic Neolithic at Mehrgarh lasting up to 3300 BC; blending into the Early Bronze Age. Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in the Indian subcontinent.[94][95] Early Mehrgarh residents lived in mud brick houses, stored their grain in granaries, fashioned tools with local copper ore, and lined their large basket containers with bitumen. They cultivated six-row barley, einkorn and emmer wheat, jujubes and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. Residents of the later period (5500 BC to 2600 BC) put much effort into crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metal working. The site was occupied continuously until about 2600 BC.

The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1700 BC, flourished 2600–1900 BC), abbreviated IVC, was an ancient civilization that flourished in the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra river valleys have been found in eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan and western India. Minor scattered sites have been found as far away as Turkmenistan. Another name for this civilization is the Harappan Civilization, after the first of its cities to be excavated, Harappa in the Pakistani province of Punjab. The IVC were known to the Sumerians as the Meluhha, and other trade contacts may have included Egypt, Africa, however, the modern world discovered it only in the 1920s as a result of archaeological excavations and rail-road building. The births of Mahavira and Buddha in the 6th century BC mark the beginning of well-recorded history in the region. Around the 5th century BC, the ancient region of Afghanistan and Pakistan was invaded by the Achaemenid Empire under Darius in 522 BC[96] forming the easternmost satraps of the Persian Empire. The provinces of Sindh and Panjab were said to be the richest satraps of the Persian Empire and contributed many soldiers to various Persian expeditions. It is known that an Indian contingent fought in Xerxes' army on his expedition to Greece. Herodotus mentions that the Indus satrapy supplied cavalry and chariots to the Persian army.[97] He also mentions that the Indus people were clad in armaments made of cotton, carried bows and arrows of cane covered with iron.[98] Herodotus states that in 517 BC Darius sent an expedition under Scylax to explore the Indus.[99] Under Persian rule, much irrigation and commerce flourished within the vast territory of the empire. The Persian empire was followed by the invasion of the Greeks under Alexander's army. Since Alexander was determined to reach the easternmost limits of the Persian Empire he could not resist the temptation to conquer India (i.e. the Punjab region), which at this time was parcelled out into small chieftain-ships, who were feudatories of the Persian Empire. Alexander amalgamated the region into the expanding Hellenic empire.[citation needed] The Rigveda, in Sanskrit, goes back to about 1500 BC. The Indian literary tradition has an oral history reaching down into the Vedic period of the later 2nd millennium BC.

Ancient India is usually taken to refer to the "golden age" of classical Indian culture, as reflected in Sanskrit literature, beginning around 500 BC with the sixteen monarchies and 'republics' known as the Mahajanapadas, stretched across the Indo-Gangetic plains from modern-day Afghanistan to Bangladesh. The largest of these nations were Magadha, Kosala, Kuru and Gandhara. Notably, the great epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata are rooted in this classical period.

Amongst the sixteen Mahajanapadas, the Kingdom of Magadha rose to prominence under a number of dynasties that peaked in power under the reign of Ashoka Maurya one of India's most legendary and famous emperors. During the reign of Ashoka, the four dynasties of Chola, Chera, and Pandya were ruling in the South, while the King Devanampiya Tissa was controlling the Anuradhapura Kingdom (now Sri Lanka). These kingdoms, while not part of Ashoka's empire, were in friendly terms with the Maurya Empire. There was a strong alliance existed between Devanampiya Tissa (250–210 BC) and Ashoka of India,[100] who sent Arahat Mahinda, four monks, and a novice being sent to Sri Lanka.[101]

They encountered Devanampiya Tissa at Mihintale. After this meeting, Devanampiya Tissa embraced Buddhism the order of monks was established in the country.[102] Devanampiya Tissa, guided by Arahat Mahinda, took steps to firmly establish Buddhism in the country.

The period between AD 320–550 is known as the Classical Age, when most of North India was reunited under the Gupta Empire (c. AD 320–550). This was a period of relative peace, law and order, and extensive achievements in religion, education, mathematics, arts, Sanskrit literature and drama. Grammar, composition, logic, metaphysics, mathematics, medicine, and astronomy became increasingly specialized and reached an advanced level. The Gupta Empire was weakened and ultimately ruined by the raids of Hunas (a branch of the Hephthalites emanating from Central Asia). Under Harsha (r. 606–47), North India was reunited briefly.

The educated speech at that time was Sanskrit, while the dialects of the general population of northern India were referred to as Prakrits. The South Indian Malabar Coast and the Tamil people of the Sangam age traded with the Graeco-Roman world. They were in contact with the Phoenicians, Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Syrians, Jews, and the Chinese.[103]

The regions of South Asia, primarily present-day India and Pakistan, were estimated to have had the largest economy of the world between the 1st and 15th centuries AD, controlling between one third and one quarter of the world's wealth up to the time of the Mughals, from whence it rapidly declined during British rule.[104]

East Asia[]

China[]

Chinese Civilization that emerged within the Yellow River Valley is one of five original civilizations in the world. Prior to the formation of civilization neolithic cultures such as the Longshan and Yangshao dating to 5,000 BC lived in wall cities and likely had social organizations of complex chiefdoms. The practice of rice cultivation was vital to settled life in China.

Chinese history records such as the Records of the Grand Historian claim of the existence of the Xia Dynasty. However, as the Xia left behind no written record themselves, the time and location of their civilization has been in doubt. Some historians believe that the neolithic Erlitou culture (1900–1600 BC) is the Xia Dynasty but whether archaeological discoveries in the area Xia Dynasty or a different culture remains in doubt. [105][106] The early part of the Shang dynasty described in traditional histories (c. 1600–1300 BC) is commonly identified with archaeological finds at Erligang, Zhengzhou and Yanshi, south of the Yellow River in modern-day Henan province. The last capital of the Shang (c. 1300–1046 BC) at Anyang (also in Henan) has been directly confirmed by the discovery there of the earliest Chinese texts, inscriptions of divination records on the bones or shells of animals – the so-called "oracle bones".

Towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Shang were overrun by the Zhou dynasty from the Wei River valley to the west. The death of King Wu of Zhou soon after the conquest triggered a succession crisis and civil war that was suppressed by Wu's brother, the Duke of Zhou, acting as regent. The Zhou rulers at this time invoked the concept of the Mandate of Heaven to legitimize their rule, a concept that would be influential for almost every successive dynasty. The Zhou initially established their capital in the west near modern Xi'an, near the Yellow River, but they would preside over a series of expansions into the Yangtze River valley. This would be the first of many population migrations from north to south in Chinese history.

In the 8th century BC, power became decentralized during the Spring and Autumn period, named after the influential Spring and Autumn Annals. In this period, local military leaders used by the Zhou began to assert their power and vie for hegemony. The situation was aggravated by the invasion of other peoples from the northwest, such as the Quanrong, forcing the Zhou to move their capital east to Luoyang. This marks the second large phase of the Zhou dynasty: the Eastern Zhou. In each of the hundreds of states that eventually arose, local strongmen held most of the political power and continued their subservience to the Zhou kings in name only. Local leaders for instance started using royal titles for themselves. The Hundred Schools of Thought of Chinese philosophy blossomed during this period, and such influential intellectual movements as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism and Mohism were founded, partly in response to the changing political world. The Spring and Autumn period is marked by a falling apart of the central Zhou power. China now consisted of hundreds of states, some only as large as a village with a fort.

After further political consolidation, seven prominent states remained by the end of the 5th century BC, and the years in which these few states battled each other is known as the Warring States period. Though there remained a nominal Zhou king until 256 BC, he was largely a figurehead and held little power. As neighboring territories of these warring states, including areas of modern Sichuan and Liaoning, were annexed, they were governed under the new local administrative system of commandery and prefecture. This system had been in use since the Spring and Autumn period and parts can still be seen in the modern system of Sheng and Xian (province and county). The final expansion in this period began during the reign of Ying Zheng, the king of Qin. His unification of the other six powers, and further annexations in the modern regions of Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong and Guangxi in 214 BC enabled him to proclaim himself the First Emperor (Qin Shi Huangdi).

Qin Shi Huangdi ruled the unified China directly with absolute power. In contrast to the decentralized and feudal rule of earlier dynasties the Qin set up a number of 'commandries' around the country which answered directly to the emperor. Nationwide the philosophy of legalism was enforced and publications promoting rival ideas such as Confucianism were prohibited. In his reign unified China created the first continuous Great Wall with the use of forced labor. Invasions were launched southward to annex Vietnam. After the emperor's death rebels rose against the Qin's brutal reign in new civil wars. Ultimately the Han Dynasty arose and ruled China for over four centuries in what accounted for a long period in prosperity, with a brief interruption by the Xin Dynasty. The Han Dynasty played a great role in developing the Silk Road which would transfer wealth and ideas for millennia, and also invented paper. Though the Han enjoyed great military and economic success it was strained by the rise of aristocrats who disobeyed the central government. Public frustration provoked the Yellow Turban Rebellion – though a failure it nonetheless accelerated the empire's downfall. After 208 AD the Han Dynasty broke up into rival kingdoms. China would remain divided until 581 under the Sui Dynasty, during the era of division Buddhism would be introduced to China for the first time.

Neighbors of China[]

The East Asian nations adjacent to China were all profoundly influenced by their interactions with Chinese civilization. Mongolia, Korea and Vietnam often were at war with, paid tribute to, or annexed by Imperial Chinese states. Yayoi Japan, though not occupied, had interactions with Imperial China that shaped its cultural development.

Mongolia in ancient times was nomadic. The ethnicities, cultures and languages in modern Mongolian territory were fluid and changed frequently. The use of horses to herd and migrate started during the Iron Age. These were Tengriist horse-riding pastoral kingdoms that had close contact with the sedentary agrarian Chinese. To appease the aggressive nomads, local Chinese rulers often gave important hostages and arranged marriages. In 208 BC the Xiongnu emperor Modu Chanyu, in his first major military campaign, defeated the Donghu, who split into the new tribes Xianbei and Wuhuan. The Xiongnu were the largest nomadic enemies of the Han Dynasty fighting wars for over three centuries with the Han Dynasty before dissolving. Afterwards the Xianbei returned to rule the Steppe north of the Great Wall. The titles of Khangan and Khan come from the Xianbei.

According to the Records of the Grand Historian by the Chinese historian Sima Qian, Wiman Joseon of Korea was founded by General Wiman from China who originally served but usurped the throne of Gojoseon (the name of ancient Korea) in 194 BC.[109] In 108 BC, the Han dynasty of China destroyed Wiman Joseon and established four commanderies on the northern Korean peninsula. Three of the commanderies were shortly lost but the Lelang commandery remained on the northwestern Korean peninsula for about 400 years. The Three Kingdoms of Korea of Baekje, Goguryeo and Silla emerged after the fall of Gojoseon and eventually expelled the Chinese. The Three Kingdoms competed with each other both economically and militarily; Goguryeo and Baekje were the main players for much of the Three Kingdoms era and controlled most of the Korean peninsula. At times more powerful than neighboring Chinese dynasties, Goguryeo (where the name "Korea" comes from) was a regional power that defeated massive invasions by the Sui dynasty multiple times.[110] Goguryeo and Baekje were eventually destroyed by a Tang dynasty and Silla alliance. Silla then drove out the Tang dynasty in 676 to control most of the Korean peninsula undisputed.

In Vietnam, archaeologists have pointed to the Phùng Nguyên culture as the beginning of the Vietnamese identity from around 2000 BC which engaged in early bronze smelting. Eight hundred years later the Đông Sơn culture arose a prehistoric Bronze Age culture that was centered at the Red River Valley of northern Vietnam. Large scale rice cultivation began around 1200 BC, onward. Pottery and Bamboo working became common in this time period as well as widespread trade and navigation on inland rivers. During this time Vietnam was allegedly ruled by the semi-mythical Hong Bang Dynasty, the last Hong king was deposed by a Chinese Qin Invasion, in turn however a Chinese General declared independence and founded the Nanyue combining Chinese and Vietnamese traditions.

Nan Yue, after a century of political maneuvers the country was annexed by the Han Dynasty in 111 B.C Originally the Han were lenient governors and attempted to integrate the Vietnamese upper class into Chinese Patriarchy. However Chinese abuse of certain vassals led to the famous but futile revolt of the Trung Sisters. Afterwards Chinese authorities ruled Vietnam directly and attempted to push Chinese culture upon the populace though peasants continued to speak Vietnamese. Vietnam would be under Chinese domination for a millennium.[111] Meanwhile, South Vietnam held a completely different identity, populated mainly by Cham People. While Northern Vietnam came under Chinese Domination, the Champa kingdom became closer to Indian kingdoms through trade and embraced Hinduism.

Japan first appeared in written records in AD 57 with the following mention in China's Book of the Later Han:[112] "Across the ocean from Luoyang are the people of Wa. Formed from more than one hundred tribes, they come and pay tribute frequently. The Book of Wei, written in the 3rd century, noted the country was the unification of some 30 small tribes or states and ruled by a shaman queen named Himiko of Yamataikoku. During the Han dynasty and Wei dynasty, Chinese travelers to Kyūshū recorded its inhabitants and claimed that they were the descendants of the Grand Count (Tàibó) of the Wu. The inhabitants also show traits of the pre-sinicized Wu people with tattooing, teeth-pulling and baby-carrying. The Book of Wei records the physical descriptions which are similar to ones on Haniwa statues, such men with braided hair, tattooing and women wearing large, single-piece clothing. Power was often decentralized until the creation of its first constitution in AD 600.

The Americas[]

In pre-Columbian times, several large, centralized ancient civilizations developed in the Western Hemisphere,[113] both in Mesoamerica and western South America. Beyond these areas, the use of agriculture expanded East of the Andes Mountains in South America particularly with the Marajoara culture, and in the continental United States with the Hopewell culture.

Andean civilizations[]

The Central Andes in South America was one of the original areas of civilization, spanning 4,500 years from the Norte chico otherwise known as Caral-Supe in 3500 BC to the final the Inca Empire after which the entire continent was transformed by the 16th century Columbian Exchange. Until the late 20th century, details about Norte Chico were unclear and often confused with later cultures such as the Chavin.

Ancient Andean Civilization began with the rise or organized fishing communities from 3,500 BC onwards. Along with a sophisticated maritime society came the construction of large monuments, which likely existed as community centers.[114] The large ceremonial structures predated the Measoamerican Olmecs by 2,000 years making Norte Chico the first civilization in the western hemisphere.

Mesoamerica[]

Mesoamerican ancient civilizations included the Olmecs and Mayans. Between 2000 and 300 BC, complex cultures began to form and many matured into advanced Mesoamerican civilizations such as the: Olmec, Izapa, Teotihuacan, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, Which flourished for nearly 4,000 years before the first contact with Europeans. These civilizations' progress included pyramid-temples, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and theology.

The Zapotec emerged around 1500 years BC. They left behind the great city Monte Albán. Their writing system had been thought to have influenced the Olmecs but, with recent evidence, the Olmec may have been the first civilization in the area to develop a true writing system independently. At the present time, there is some debate as to whether or not Olmec symbols, dated to 650 BC, are actually a form of writing preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 BC.[115]

Olmec symbols found in 2002 and 2006 date to 650 BC[116] and 900 BC[117] respectively, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing.[118][119] The Olmec symbols found in 2006, dating to 900 BC, are known as the Cascajal Block. The earliest Mayan inscriptions found which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century BC in San Bartolo, Guatemala. The Mayan invention of writing makes Mesoamerica one of only three regions in the world that developed writing completely independently.[120]

Northern America[]

Organized societies, in the ancient United States or Canada, were often mound builder civilizations. One of the most significant of these was the Poverty Point Culture that existed in the U.S state of Louisiana, and was responsible for the creation of over 100 mound sites. The Mississippi River was a core area in the development of long-distance trade and culture. Following Poverty Point, successive complex cultures such as the Hopewell emerged in the Southeastern United States in the Early Woodland period. Before 500 AD many mound builder societies, retained a hunter gatherer form of subsistence.

Europe[]

Etruria, Greece and Rome[]

The history of the Etruscans can be traced relatively accurately, based on the examination of burial sites, artifacts, and writing. Etruscans culture that is identifiably and certainly Etruscan developed in Italy in earnest by 900 BC approximately with the Iron Age Villanovan culture, regarded as the oldest phase of Etruscan civilization.[123][124][125][126][127] The latter gave way in the 7th century to an increasingly orientalizing culture that was influenced by Greek traders and Greek neighbors in Magna Graecia, the Hellenic civilization of southern Italy, evidenced by around 13,000 inscriptions in an alphabet similar to that of Euboean Greek, in the Pre-Indo-European Etruscan language. The burial tombs, some of which had been fabulously decorated, promotes the idea of an aristocratic city-state, with centralized power structures maintaining order and constructing public works, such as irrigation networks, roads, and town defenses.

Ancient Greece is the period in Greek history lasting for close to a millennium, until the rise of Christianity. It is considered by most historians to be the foundational culture of Western Civilization. Greek culture was a powerful influence in the Roman Empire, which carried a version of it to many parts of Europe.

The earliest known human settlements in Greece were on the island of Crete, more than 9,000 years ago, though there is evidence of tool use on the island going back over 100,000 years.[128] The earliest evidence of a civilisation in ancient Greece is that of the Minoans on Crete, dating as far back as 3600 BC. On the mainland, the Mycenaean civilisation rose to prominence around 1600 BC, superseded the Minoan civilisation on Crete, and lasted until about 1100 BC, leading to a period known as the Greek Dark Ages.

The Archaic Period in Greece is generally considered to have lasted from around the 8th century BC to the invasion by Xerxes in 480 BC. This period saw the expansion of the Greek world around the Mediterranean, with the founding of Greek city-states as far afield as Sicily in the West and the Black sea in the East.[129] Politically, the Archaic period in Greece saw the collapse of the power of the old aristocracies,[130] with democratic reforms in Athens and the development of Sparta's unique constitution. The end of the Archaic period also saw the rise of Athens, which would come to be a dominant power in the Classical period, after the reforms of Solon and the tyranny of Pisistratus.[130]

The Classical Greek world was dominated throughout the 5th century BC by the major powers of Athens and Sparta. Through the Delian League, Athens was able to convert Pan-hellenist sentiment and fear of the Persian threat into a powerful empire, and this, along with the conflict between Sparta and Athens culminating in the Peloponnesian war, was the major political development of the first part of the Classical period.[131]

The period in Greek history from the death of Alexander the Great until the rise of the Roman empire and its conquest of Egypt in 30 BC is known as the Hellenistic period. The name derives from the Greek word Hellenistes ("the Greek speaking ones"), and describes the spread of Greek culture into the non-Greek world following the conquests of Alexander and the rise of his successors.

Following the Battle of Corinth in 146 BC, Greece came under Roman rule, ruled from the province of Macedonia. In 27 BC, Augustus organised the Greek peninsula into the province of Achaea. Greece remained under Roman control until the break up of the Roman empire, in which it remained part of the Eastern Empire. Much of Greece remained under Byzantine control until the end of the Byzantine empire in 1453 AD.