Margarete Buber-Neumann

Margarete Buber-Neumann | |

|---|---|

| Born | Margarete Thüring 21 October 1901 |

| Died | 6 November 1989 (aged 88) Frankfurt am Main, West Germany |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Writer |

| Years active | 1921–1978 |

| Known for | Witness to concentration camps in Nazi Germany and Stalinist USSR during WWII |

Notable work | Under Two Dictators (1949) |

| Political party | Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD) |

| Spouse(s) | Rafael Buber, Helmuth Faust |

| Partner(s) | Heinz Neumann |

| Parent(s) | Heinrich Thüring, Else Merten |

| Relatives | siblings (Lisette, Gertrud, two brothers), children (Barbara, Judith) |

| Awards | Bundesverdienstkreuz (1980) |

Margarete Buber-Neumann (21 October 1901 – 6 November 1989), a German communist, wrote the memoir Under Two Dictators about her imprisonment within a Soviet prison, and later a Nazi concentration camp during World War II. She was also known for having testified in the so-called "trial of the century" about the Kravchenko Affair in France.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Background[]

Margarete Thüring was born on 21 October 1901, in Potsdam, Germany. Her father, Heinrich Thüring (1866–1942), was a master brewer; her mother was Else Merten (1871–1960). She had four siblings: Lisette (known as "Babette"), Gertrud ("Trude"), and two brothers, Heinrich and Hans.[2][3][4][5][6][8][9][10][11]

Career[]

In 1919, Buber-Neumann enrolled at Pestalozzi-Fröbel Haus in Berlin to learn to teach kindergarten. In 1921, she attended a memorial for Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. That same year, she joined the Socialist Youth League. In 1926, she joined the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD) (the Communist Party of Germany). She obtained a job as an editor for the International Press Correspondence ("Inprecor" or "Inprekorr" in German).[9][10][11]

In 1929, she met her second husband, Heinz Neumann, Comintern representative to Germany. In 1931–32, they visited the Soviet Union twice and then Spain.[10] In November 1933, Neumann received a recall from Moscow but instead left for Switzerland.[10][11] In December 1934, Neumann was arrested and expelled from Switzerland.[11] After Neumann's release in 1935, the couple moved to Paris, where they worked with Willi Münzenberg (who married Buber-Neumann's sister, Babette).[6][9][11] In May 1935, the Comintern ordered them back to Moscow to serve as translators at the Foreign Workers Publishing House.[1][2][3][4][6][8][9][10][11][12]

Internment[]

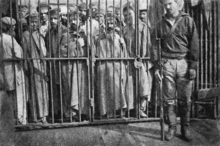

On 27 April 1937, while living at Moscow's Hotel Lux, Heinz Neumann was arrested as part of Joseph Stalin's Great Purge and later executed.[1][3][4][10] Buber-Neumann never learned her husband's exact fate (later known as executed on 26 November 1937).[11] On 19 June 1938, she herself was arrested, held at the Lubianka prison, then Butyrka, and then sent to labour camps, first in Karaganda, then in Birma, Kazakhstan.[1][3][4][5][6][8][10][11][13] as a "wife of an enemy of the people."[14]

In February 1940, the Soviets included her in a prisoner exchange with the Nazis,[2][3][10][11] which was part of the NKVD-Gestapo cooperation[15] initiated by Ribbentropp-Molotov pact. She was sent to Germany along with some other Soviet political prisoners, including Betty Olberg, a wife of another German communist (who was executed in 1936).[16]

She was then detained with other "political prisoners" in Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she became friends with Orli Wald[17] and Milena Jesenská.[1][3][5][10][11] She survived five years in the camp.

She later wrote:

The SS had no fabric for the production of new prison clothing. Instead they drove truckloads of coats, dresses, underwear and shoes that had once belonged to those gassed in the east, to Ravensbrück... The clothes of the people were sorted, and at first crosses were cut out, and fabric of another color sewn underneath. The prisoners walked around like sheep marked for slaughter. The crosses would impede escape. Later they spared themselves this cumbersome procedure and painted with oil paint broad, white crosses on the coats.

(NOTE: Translated from the Swedish edition Fånge hos Hitler och Stalin (1949)

Buber-Neumann worked in a clerical capacity in the Siemens plant attached to the camp and later as secretary to a camp official, SS-Oberaufseherin Johanna Langefeld.[1] She was freed on 21 April 1945, and stayed with her mother in Bavaria.[1][2][5][8][10][11][12]

Under Two Dictators[]

After World War II, Buber-Neumann accepted an invitation to live in Sweden, where she lived and worked for three years.[2][8][10] In 1948, she published Als Gefangene bei Stalin und Hitler (published in German and Swedish, then the following year in French and English as Under Two Dictators: Prisoner of Stalin and Hitler) in 1949. At the urging of her friend Arthur Koestler, in this book she gave an account of her years in both Soviet prison and Nazi concentration camps.[10][18] The book aroused the bitter hostility of the Soviet and German communists.[1][9][10][11][12]

Kravchenko Affair[]

On 23 February 1949, Buber-Neumann testified in Paris in support of Victor Kravchenko, who was suing a French magazine connected with the French Communist Party for libel after it accused him of fabricating his account of Soviet labor camps. Buber-Neumann corroborated Kravchenko's account in great detail, contributing to his victory in the case.[7][9][11][12][19][20]

Anti-communism[]

In 1950, Buber-Neumann returned to Germany and settled in Frankfurt-am-Main as a staunch anti-communist. She continued to write for the next three decades. The same year, she joined the anti-communist Congress for Cultural Freedom with Arthur Koestler, Bertrand Russell, Karl Jaspers, Jacques Maritain, Raymond Aron, A. J. Ayer, Ignazio Silone, Nicola Chiaromonte, and Sidney Hook.[21]

In 1951, she became editor of the political journal Die Aktion. In 1957, she published Von Potsdam nach Moskau: Stationen eines Irrweges ("From Potsdam to Moscow: Stations of an Erring Way").[11] In 1959, Arthur Koestler asked her to join him at his home in Alpbach to meet Whittaker Chambers and his wife Esther Shemitz while they were visiting Europe. On 24 June 1959, Chambers wrote in a letter:

Then K had the idea to wire Greta Buber-Neumann: "Komme schleunigst. Gute Weine. Außerdem, Whittaker C."...There we sat and talked, not merely about the experiences of our life... We realized that, of our particular breed, the old activitists, we are almost the only survivors – the old activists who were articulate, consequent revolutionists, and not merely agents.[22]

In 1963, she published a biography of her Ravensbrück friend Milena Jesenská Kafkas Freundin Milena. In 1976, she published Die erloschene Flamme: Schicksale meiner Zeit (The Extinct Flame: Fates of My Time), in which she argued that Nazism and Communism were in practice the same.[11] Regarding Communism and Nazism, Buber-Neumann wrote:

Between the misdeeds of Hitler and those of Stalin, in my opinion, there exists only a quantitative difference... I don't know if the Communist idea, if its theory, already contained a basic fault or if only the Soviet practice under Stalin betrayed the original idea and established in the Soviet Union a kind of Fascism. (Under Two Dictators, 2008 edition, page 300)

By this time, she had become a political conservative, joining the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in 1975.

Personal life[]

In 1920, Buber-Neumann's sister, , had married Fritz Gross of Vienna, who moved to Germany after World War I and became a member of the KPD. They had a son in 1923, then separated. Babette retained her married name of "Babette Gross" for the rest of her life. (Fritz Gross moved to England in the 1930s, helped refugees during World War II, and died in 1946 with a considerable corpus of mostly unpublished work.)[23] Gross then became the spouse of Willi Münzenberg, under whom Otto Katz and Arthur Koestler worked in Paris. In Münzenberg's office, Koestler met both sisters.[18] Koestler would remain a friend after both he and Buber-Neumann left the party. (As "Babette Gross", Buber-Neuman's sister later wrote a biography of Münzenberg.[24])

In 1921 or 1922 Margarete Thüring married , communist son of the philosopher Martin Buber. Following her divorce in 1929, she lived in unmarried union[25] with Heinz Neumann.[2][3][8][9] She married Helmuth Faust after she went to live in Frankfurt-am-Main; they divorced.[10][11]

Death[]

Buber-Neumann died age 88 on November 6, 1989, in Frankfurt am Main–three days before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Her daughters are Barbara (1921–2013) and Judith (1926–2018) by her marriage to Rafael Buber. In 1928, the grandparents (Martin Buber and wife Paula Winkler) won custody of her daughters; in 1938 they all moved to Mandatory Palestine.[2][8][3][11][26][27]

Legacy[]

Poet Adeline Baldacchino wrote:

Margarete Buber-Neumann traverse le XXe siècle avec un bien triste privilège : elle est la seule à avoir publiquement témoigné par écrit de sa double expérience des camps soviétiques et nazis. La jeune et fervente communiste, accusée de « déviationnisme » par le pouvoir stalinien, survit à trois ans de Goulag sibérien pour se retrouver déportée à Ravensbrück après le pacte germano-soviétique, pendant cinq ans. Elle survivra pour raconter, inlassablement, sans amertume et sans illusions, ce que le pouvoir fait de ceux qui le détiennent et à ceux qu’il détient.

Margarete Buber-Neumann had the sad privilege to span the 20th century as the only person to have testified publicly in writing about the experience of both Soviet and Nazi camps. The young and fervent communist, accused of "deviationism" by Stalinist powers, survived three years of the Siberian Gulag only to be deported to Ravensbrück after the German-Soviet pact for five years. She would survive to tell, tirelessly, without bitterness and without illusions, what power does to those who hold it and to those whom it holds.[12]

Historian Tony Judt held her among one of "the most important political writers, social commentators, or public moralists of the age" in a list that includes Émile Zola, Václav Havel, Karl Kraus, Alva Myrdal, and Sidney Hook.[7] Judt wrote that she had written one of the best accounts by an ex-communist and listed her among Albert Camus, Ignazio Silone, Manès Sperber, Arthur Koestler, Jorge Semprún, Wolfgang Leonhard, and Claude Roy.[7]

Writer chose Buber-Neumann as with Ruth Klüger, Marguerite Duras, and Charlotte Delbo as "main witnesses" to "reflect on the relationship between history and literature, or between the materiality of pain (the experience of body) and its representation in text."[28]

Awards[]

In 1980, Buber-Neumann received the Great Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Works[]

- Fånge hos Hitler och Stalin (1948)[29]

- Von Potsdam nach Moskau: Stationen eines Irrweges (1957)

- Kafkas Freundin Milena (1963) – Mistress to Kafka: the life and death of Milena; introduction by Arthur Koestler (1966)

- Milena, translated by Ralph Manheim[33]

- Kommunistische Untergrund. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der kommunistischen Geheimarbeit (1970)

- Dokumentation einer Manipulation (1972)

- Freiheit, du bist wieder mein ..." : d. Kraft zu überleben (1978)

- Plädoyer für Freiheit und Menschlichkeit: Vorträge aus 35 Jahren – Janine Platten und Judith Buber Agassi (2000)

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1949). Under Two Dictators: Prisoner of Stalin and Hitler. Gollancz. pp. xi (1935), 4 (husband's arrest), 112 (Karaganda), 260–261 (Siemens), 277–286 (Milena), 300–314 (1945). Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Margarete Buber-Neumann". Frauen.Biographieforshung. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Margarete Buber-Neumann". Penguin UK. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Days and Lives: Prisoners: Margarete Buber-Neumann". Gulag History. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Margarete Buber-Neumann". Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNB). Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1901–1989)". Universalis. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Judt, Tony (17 April 2008). Reappraisals: Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century. Penguin. ISBN 9781440634550. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Margarete Buber-Neumann". Random House Australia. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Gutiérrez-Álvarez, Pepe (18 October 2005). "The Story of Margarete Buber-Neumann: The German communist that Stalin delivered to Hitler". Viento Sur. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Brauer, Stefanie (23 October 2001). "Zum 100. Geburtstag von Margarete Buber-Neumann: Ein aufrechter Gang". Die Gazette. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1901–1989)". Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. 2002. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Baldacchino, Adeline (19 March 2018). "Margarete Buber-Neumann — survivre au siècle des barbelés". RevueBallast. Retrieved 13 May 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Books: One Who Survived, Time, 15 January 1951; retrieved 13 November 2011. (subscription required)

- ^ Hermann Weber, Hotel Lux – Die deutsche kommunistische Emigration in Moskau (PDF) Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung No. 443 (October 2006), p. 60; retrieved 12 November 2011. (in German)

- ^ "Auslieferung 1939/41". www.nkwd-und-gestapo.de. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ "Figure of the week: 80". EU vs DISINFORMATION. 2020-02-25. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Manfred Menzel, Brochure about Orli Wald (PDF) Hannover Municipal Archive; retrieved 14 July 2011. (in German)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scammell, Michael (2010). Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic. New York: Random House. pp. 105, 351. ISBN 9781588369017. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Beevor, Antony; Cooper, Artemis (1994). Paris After the Liberation: 1944–1949. Hamish Hamilton. p. 412. ISBN 9780241134375. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Vogt, Sebastian (2015). "Über die Bedeutung des Kravčenko-Prozesses 1949 in Paris für die politische Entwicklung Margarete Buber-Neumanns". Kommunismus Geschichte - Jahrbuch für Historische Kommunismusforschung. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Judt, Tony (5 September 2006). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. Penguin. p. 222. ISBN 9781440624766. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1969). William F. Buckley Jr. (ed.). Odyssey of a Friend. New York: Putnam. pp. 249–51. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Gross, Fritz: unpublished writings". Archives in London and the M25 area. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Gross, Babette (1974). Willi Münzenberg: A Political Biography. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press.

- ^ Arthur Koestler, The Invisible Writing. London: Hutchinson of London, 1979, p. 255

- ^ "Prof. Judith Buber Agassi". Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Tirzah Agassi – Obituary". Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Loew, Camila (2011). The Memory of Pain: Women's Testimonies of the Holocaust. Rodopi. p. xvii. ISBN 978-9401207065. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1948). Fånge hos Hitler och Stalin: Als Gefangene bei Stalin und Hitler. Natur och kultur. LCCN 50027706.

- ^ Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1948). Als Gefangene bei Stalin und Hitler. Verlag der Zwölf. LCCN 49029725.

- ^ Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1949). Déportée en Sibérie. Baconnière. LCCN 50015683.

- ^ Buber-Neumann, Margarete (1949). Under Two Dictators. Gollancz (UK), Dodd, Mead & Company (US). LCCN 49006527.

- ^ Buber-Neumann, Margarete. Milena: The Tragic Story of Kafka's Great Love. Arcade. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

32. Green, John, Willi Münzenberg – Fighter against Fascism and Stalinism, Routledge 2019

External links[]

- Margarete Buber-Neumann at IMDb

- Corbis photo

- Fundación Andreu Nin (Spanish)

- 1901 births

- 1989 deaths

- German communists

- Ravensbrück concentration camp survivors

- Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union

- Foreign Gulag detainees

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Burials at Frankfurt Main Cemetery

- German anti-communists

- 20th-century German women writers