Medieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from c. 950 to c. 1250.[2] It was likely[3] related to temperature increases elsewhere,[4][5][6] but other regions meanwhile got colder, such as the tropical Pacific. Average global mean temperatures have been calculated to be similar to the early-mid-20th-century warming. Possible causes of the Medieval Warm Period include increased solar activity, decreased volcanic activity, and changes in ocean circulation.[7]

The Medieval Warm Period was followed by a cooler period in the North Atlantic and elsewhere, which is termed the Little Ice Age. Some refer to the event as the Medieval Climatic Anomaly to emphasize that climatic effects other than temperature were also important.[8][9]

It is thought that between c. 950 and c. 1100 was the Northern Hemisphere's warmest period since the Roman Warm Period. It was only in the 20th and the 21st centuries that the Northern Hemisphere has experienced higher temperatures.[citation needed] Climate proxy records show peak warmth occurred at different times for different regions, which indicate that the Medieval Warm Period was not a globally-uniform event.[10]

Initial research[]

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP) is generally thought to have occurred from c. 950–c. 1250, during the European Middle Ages.[2] In 1965, Hubert Lamb, one of the first paleoclimatologists, published research based on data from botany, historical document research, and meteorology, combined with records indicating prevailing temperature and rainfall in England around c. 1200 and around c. 1600. He proposed, "Evidence has been accumulating in many fields of investigation pointing to a notably warm climate in many parts of the world, that lasted a few centuries around c. 1000–c. 1200 AD, and was followed by a decline of temperature levels till between c. 1500 and c. 1700 the coldest phase since the last ice age occurred."[11]

The warm period became known as the Medieval Warm Period, and the cold period was called the Little Ice Age (LIA). However, that view was questioned by other researchers. The IPCC First Assessment Report of 1990 discussed the "Medieval Warm Period around 1000 AD (which may not have been global) and the Little Ice Age which ended only in the middle to late nineteenth century." It stated that temperatures in the "late tenth to early thirteenth centuries (about AD 950-1250) appear to have been exceptionally warm in western Europe, Iceland and Greenland."[12] The IPCC Third Assessment Report from 2001 summarized newer research: "evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this time frame, and the conventional terms of 'Little Ice Age' and 'Medieval Warm Period' are chiefly documented in describing northern hemisphere trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries."[13]

Global temperature records taken from ice cores, tree rings, and lake deposits have shown that the Earth may have been slightly cooler globally (by 0.03 °C) than in the early and the mid-20th century.[14][15]

Palaeoclimatologists developing region-specific climate reconstructions of past centuries conventionally label their coldest interval as "LIA" and their warmest interval as the "MWP."[14][16] Others follow the convention, and when a significant climate event is found in the "LIA" or "MWP" timeframes, they associate their events to the period. Some "MWP" events are thus wet events or cold events, rather than strictly warm events, particularly in central Antarctica, where climate patterns that are opposite to those of the North Atlantic have been noticed.

Globally[]

A 2009 study by Michael E. Mann et al., examining spatial patterns of surface temperatures shown in multi-proxy reconstructions, found that evidence on the Medieval Warm Period shows "warmth that matches or exceeds that of the past decade in some regions, but which falls well below recent levels globally."[2] Their reconstruction of the pattern is characterised by warmth over a large part of the North Atlantic Ocean, southern Greenland, the Eurasian Arctic, and parts of North America that appears to be substantially higher than that of the late 20th century (1961–1990) baseline and to be comparable or to exceed that of the past decade or two in some regions. On the other hand, certain regions, such as central Eurasia, northwestern North America, and (with less confidence) parts of the South Atlantic, exhibit anomalous coolness.

In 2013, a study by the Pages-2k consortium suggests the warming was not globally synchronous: "Our regional temperature reconstructions also show little evidence for globally synchronized multi-decadal shifts that would mark well-defined worldwide MWP and LIA intervals. Instead, the specific timing of peak warm and cold intervals varies regionally, with multi-decadal variability resulting in regionally specific temperature departures from an underlying global cooling trend."[17] In direct contrast to those findings, a 2013 study recreated a "temperature record of western equatorial Pacific subsurface and intermediate water masses over the past 10,000 years that shows that heat content varied in step with both Northern and Southern high-latitude oceans. The findings support the view that the Holocene Thermal Maximum, the Medieval Warm Period, and the Little Ice Age were global events, and they provide a long-term perspective for evaluating the role of ocean heat content in various warming scenarios for the future."[18]

In 2019, by using an extended proxy data set,[19] the Pages-2k consortium confirmed that the Medieval Climate Anomaly was not a globally-synchronous event. The warmest 51-year period within the Medieval Warm Period did not occur at the same time in different regions. They argue for a regional instead of global framing of climate variability in the preindustrial Common Era to aid in understanding.[20]

In August 2021, the 6th IPCC report indicated that global temperature was 4°C– 10°C warmer during the MCO than 1850-1900.[21]

North Atlantic[]

Lloyd D. Keigwin's 1996 study of radiocarbon-dated box core data from marine sediments in the Sargasso Sea found that its sea surface temperature was approximately 1 °C (1.8 °F) cooler approximately 400 years ago, during the Little Ice Age, and 1700 years ago and was approximately 1 °C warmer 1000 years ago, during the Medieval Warm Period.[22]

Using sediment samples from Puerto Rico, the Gulf Coast, and the Atlantic Coast from Florida to New England, Mann et al. (2009) found consistent evidence of a peak in North Atlantic tropical cyclone activity during the Medieval Warm Period, which was followed by a subsequent lull in activity.[23]

By retrieval and isotope analysis of marine cores and from examination of mollusc growth patterns from Iceland, Patterson et al. reconstructed a mollusk growth record at a decadal resolution from the Roman Warm Period to the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.[24]

North America[]

The 2009 Mann et al. study found warmth exceeding 1961–1990 levels in southern Greenland and parts of North America during the Medieval Climate Anomaly, which the study defines as from 950 to 1250, with warmth in some regions exceeding temperatures of the 1990–2010 period. Much of the Northern Hemisphere showed a significant cooling during the Little Ice Age, which the study defines as from 1400 to 1700, but Labrador and isolated parts of the United States appeared to be approximately as warm as during the 1961–1990 period.[2]

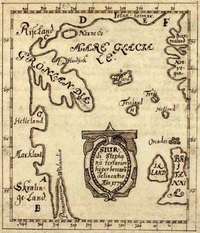

The Norse colonization of the Americas has been associated with warmer periods. The common theory is that Norsemen took advantage of ice-free seas to colonize areas in Greenland and other outlying lands of the far north.[25] However, a study from Columbia University suggests that Greenland was not colonized in warmer weather, but the warming effect in fact lasted for only very briefly.[26] c. 1000AD, the climate was sufficiently warm for the Vikings to journey to Newfoundland and to establish a short-lived outpost there.[27]

In around 985, Vikings founded the Eastern Settlement and Western Settlement, both near the southern tip of Greenland. In the colony's early stages, they kept cattle, sheep, and goats, with around a quarter of their diet from seafood. After the climate became colder and stormier around 1250, their diet steadily shifted towards ocean sources. By around 1300, seal hunting provided over three quarters of their food.

By 1350, there was reduced demand for their exports, and trade with Europe fell away. The last document from the settlements dates from 1412, and over the following decades, the remaining Europeans left in what seems to have been a gradual withdrawal, which was caused mainly by economic factors such as increased availability of farms in Scandinavian countries.[28]

In Chesapeake Bay (now in Maryland and Virginia, United States), researchers found large temperature excursions (changes from the mean temperature of that time) during the Medieval Warm Period (about 950–1250) and the Little Ice Age (about 1400–1700, with cold periods persisting into the early 20th century), which are possibly related to changes in the strength of North Atlantic thermohaline circulation.[29] Sediments in of the lower Hudson Valley show a dry Medieval Warm Period from 800 to 1300.[30]

Prolonged droughts affected many parts of the Western United States and especially eastern California and the west of Great Basin.[14][31] Alaska experienced three intervals of comparable warmth: 1–300, 850–1200, and since 1800.[32] Knowledge of the Medieval Warm Period in North America has been useful in dating occupancy periods of certain Native American habitation sites, especially in arid parts of the Western United States.[33][34] Droughts in the Medieval Warm Period may have impacted Native American settlements also in the Eastern United States, such as at Cahokia.[35][36] Review of more recent archaeological research shows that as the search for signs of unusual cultural changes has broadened, some of the early patterns (such as violence and health problems) have been found to be more complicated and regionally varied than had been previously thought. Other patterns, such as settlement disruption, deterioration of long-distance trade, and population movements, have been further corroborated.[37]

Africa[]

The climate in equatorial eastern Africa has alternated between being drier than today and relatively wet. The climate was drier during the Medieval Warm Period (1000–1270).[38]

Antarctica[]

A sediment core from the eastern Bransfield Basin, in the Antarctic Peninsula, preserves climatic events from both the Little Ice Age and the Medieval Warm Period. The authors noted, "The late Holocene records clearly identify Neoglacial events of the Little Ice Age (LIA) and Medieval Warm Period (MWP)."[39] Some Antarctic regions were atypically cold, but others were atypically warm between 1000 and 1200.[40]

Pacific Ocean[]

Corals in the tropical Pacific Ocean suggest that relatively cool and dry conditions may have persisted early in the millennium, which is consistent with a La Niña-like configuration of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation patterns.[41]

In 2013, a study from three US universities was published in Science magazine and showed that the water temperature in the Pacific Ocean was 0.9 degrees warmer during the Medieval Warmth Period than during the Little Ice Age and 0.65 degrees warmer than the decades before the study.[42]

South America[]

The Medieval Warm Period has been noted in Chile in a 1500-year lake bed sediment core,[43] as well as in the Eastern Cordillera of Ecuador.[44]

A reconstruction, based on ice cores, found that the Medieval Warm Period could be distinguished in tropical South America from about 1050 to 1300 and was followed in the 15th century by the Little Ice Age. Peak temperatures did not rise as to the level of the late 20th century, which were unprecedented in the area during the study period of 1600 years.[45]

Asia[]

Adhikari and Kumon (2001), investigating sediments in Lake Nakatsuna, in central Japan, found a warm period from 900 to 1200 that corresponded to the Medieval Warm Period and three cool phases, two of which could be related to the Little Ice Age.[46] Other research in northeastern Japan showed that there was one warm and humid interval, from 750 to 1200, and two cold and dry intervals, from 1 to 750 and from 1200 to now.[47] Ge et al. studied temperatures in China for the past 2000 years and found high uncertainty prior to the 16th century but good consistency over the last 500 years highlighted by the two cold periods, 1620s–1710s and 1800s–1860s, and the 20th-century warming. They also found that the warming from the 10th to the 14th centuries in some regions might be comparable in magnitude to the warming of the last few decades of the 20th century, which was unprecedented within the past 500 years.[48]

Oceania[]

There is an extreme scarcity of data from Australia for both the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. However, evidence from wave-built shingle terraces for a permanently-full Lake Eyre[49] during the 9th and the 10th centuries is consistent with a La Niña-like configuration, but the data are insufficient to show how lake levels varied from year to year or what climatic conditions elsewhere in Australia were like.

A 1979 study from the University of Waikato found, "Temperatures derived from an 18O/16O profile through a stalagmite found in a New Zealand cave (40.67°S, 172.43°E) suggested the Medieval Warm Period to have occurred between AD c. 1050 and c. 1400 and to have been 0.75 °C warmer than the Current Warm Period."[50] More evidence in New Zealand is from an 1100-year tree-ring record.[51]

See also[]

- Classic Maya collapse – concurrent with the Medieval Warm Period and marked by decades long droughts

- Cretaceous Thermal Maximum – Period of climatic warming that reached its peak approximately 90 million years ago

- Description of the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age in IPCC reports

- Historical climatology

- Holocene climatic optimum – Global warm period around 9,000–5,000 years ago

- Hockey stick graph – Graph in climate science

- Late Antique Little Ice Age

- Paleoclimatology – Study of changes in ancient climate

References[]

- ^ Hawkins, Ed (January 30, 2020). "2019 years". climate-lab-book.ac.uk. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. ("The data show that the modern period is very different to what occurred in the past. The often quoted Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age are real phenomena, but small compared to the recent changes.")

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mann, M. E.; Zhang, Z.; Rutherford, S.; et al. (2009). "Global Signatures and Dynamical Origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly" (PDF). Science. 326 (5957): 1256–60. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1256M. doi:10.1126/science.1177303. PMID 19965474. S2CID 18655276.

- ^ Rosenthal, Y.; Linsley, B. K.; Oppo, D. W. (2013). "Pacific Ocean Heat Content During the Past 10,000 Years". Science. 342 (6158): 617–621. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..617R. doi:10.1126/science.1240837. PMID 24179224. S2CID 140727975.

- ^ Grove, Jean M.; Switsur, Roy (1994). "Glacial geological evidence for the medieval warm period" (PDF). Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 143. Bibcode:1994ClCh...26..143G. doi:10.1007/BF01092411. S2CID 189878617.

- ^ Diaz, Henry F.; Hughes, M. (1994). The Medieval warm period. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7923-2842-1.

6.2 Evidence for a Medieval Warm Epoch

- ^ Li, H.; Ku, T. (2002). "Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Periods in Eastern China as Read from the Speleothem Records". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 71: 71C–09. Bibcode:2002AGUFMPP71C..09L.

- ^ "How does the Medieval Warm Period compare to current global temperatures?". SkepticalScience. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ Bradley, Raymond S. (2003). "Climate of the Last Millennium" (PDF). Climate System Research Center.

- ^ Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy (1971). Times of Feast, Times of Famine: a History of Climate Since the Year 1000. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-52122-6.[page needed]

- ^ Solomon, Susan Snell; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). "6.6 The Last 2,000 Years". Climate change 2007: the physical science basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. ISBN 978-0-521-70596-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Box 6.4

- ^ Lamb, H.H. (1965). "The early medieval warm epoch and its sequel". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 1: 13–37. Bibcode:1965PPP.....1...13L. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(65)90004-0.

- ^ IPCC First Assessment Report Working Group 1 report, Chapter 7, Executive Summary p. 199, Climate Of The Past 5,000,000 Years p.202.

- ^ Folland, C.K.; Karl, T.R.; Christy, J.R.; et al. (2001). "2.3.3 Was there a "Little Ice Age" and a "Medieval Warm Period"?"". In Houghton, J.T.; Ding, Y.; Griggs, D.J.; Noguer, M.; van der Linden; Dai; Maskell; Johnson (eds.). Working Group I: The Scientific Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Climate Change 2001. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 881. ISBN 978-0-521-80767-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bradley, R. S.; Hughes, MK; Diaz, HF (2003). "CLIMATE CHANGE: Climate in Medieval Time". Science. 302 (5644): 404–5. doi:10.1126/science.1090372. PMID 14563996. S2CID 130306134.

- ^ Crowley, Thomas J.; Lowery, Thomas S. (2000). "How Warm Was the Medieval Warm Period?". AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 29: 51–54. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-29.1.51. S2CID 86527510.

- ^ Jones, P. D.; Mann, M. E. (2004). "Climate over past millennia". Reviews of Geophysics. 42 (2): 2002. Bibcode:2004RvGeo..42.2002J. doi:10.1029/2003RG000143.

- ^ https://www.blogs.uni-mainz.de/fb09climatology/files/2012/03/Pages_2013_NatureGeo.pdf

- ^ Rosenthal, Y.; Linsley, B. K.; Oppo, D. W. (2013). "Pacific Ocean Heat Content During the Past 10,000 Years". Science. 342 (6158): 617–621. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..617R. doi:10.1126/science.1240837. PMID 24179224. S2CID 140727975.

- ^ Emile-Geay, Julien; McKay, Nicholas P.; Kaufman, Darrell S.; von Gunten, Lucien; Wang, Jianghao; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Abram, Nerilie J.; Addison, Jason A.; Curran, Mark A.J.; Evans, Michael N.; Henley, Benjamin J. (2017-07-11). "A global multiproxy database for temperature reconstructions of the Common Era". Scientific Data. 4 (1): 170088. Bibcode:2017NatSD...470088E. doi:10.1038/sdata.2017.88. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 5505119. PMID 28696409.

- ^ Neukom, Raphael; Steiger, Nathan; Gómez-Navarro, Juan José; Wang, Jianghao; Werner, Johannes P. (2019). "No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era". Nature. 571 (7766): 550–554. Bibcode:2019Natur.571..550N. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1401-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31341300. S2CID 198494930.

- ^ "AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis — IPCC".

- ^ Keigwin, L. D. (1996). "The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period in the Sargasso Sea". Science. 274 (5292): 1504–1508. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1504K. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1504. PMID 8929406. S2CID 27928974.

- ^ Mann, Michael E.; Woodruff, Jonathan D.; Donnelly, Jeffrey P.; Zhang, Zhihua (2009). "Atlantic hurricanes and climate over the past 1,500 years". Nature. 460 (7257): 880–3. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..880M. doi:10.1038/nature08219. hdl:1912/3165. PMID 19675650. S2CID 233167.

- ^ Patterson, W. P.; Dietrich, K. A.; Holmden, C.; Andrews, J. T. (2010). "Two millennia of North Atlantic seasonality and implications for Norse colonies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (12): 5306–10. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5306P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902522107. PMC 2851789. PMID 20212157.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303655-5.[page needed]

- ^ "Study Undercuts Idea That 'Medieval Warm Period' Was Global - The Earth Institute - Columbia University". www.earth.columbia.edu. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Ingstad, Anne Stine (2001). "The Excavation of a Norse Settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland". In Helge Ingstad; Anne Stine Ingstad (eds.). The Viking Discovery of America. New York: Checkmark. pp. 141–169. ISBN 978-0-8160-4716-1. OCLC 46683692.

- ^ Stockinger, Günther (10 January 2012). "Archaeologists Uncover Clues to Why Vikings Abandoned Greenland". Der Spiegel Online. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age and 20th Century Temperature Variability from Chesapeake Bay". USGS. Archived from the original on 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ "Marshes Tell Story Of Medieval Drought, Little Ice Age, And European Settlers Near New York City". Earth Observatory News. May 19, 2005. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Stine, Scott (1994). "Extreme and persistent drought in California and Patagonia during mediaeval time". Nature. 369 (6481): 546–549. Bibcode:1994Natur.369..546S. doi:10.1038/369546a0. S2CID 4315201.

- ^ Hu, F. S. (2001). "Pronounced climatic variations in Alaska during the last two millennia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (19): 10552–10556. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810552H. doi:10.1073/pnas.181333798. PMC 58503. PMID 11517320.

- ^ Dean, Jeffrey S. (1994). "The medieval warm period on the southern Colorado Plateau". Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 225–241. Bibcode:1994ClCh...26..225D. doi:10.1007/BF01092416. S2CID 189877071.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Los Osos Back Bay, Megalithic Portal, editor A. Burnham.

- ^ Benson, Larry V.; Pauketat, Timothy R.; Cook, Edward R. (2009). "Cahokia's Boom and Bust in the Context of Climate Change". American Antiquity. 74 (3): 467–483. doi:10.1017/S000273160004871X. ISSN 0002-7316. S2CID 160679096.

- ^ White, A. J.; Stevens, Lora R.; Lorenzi, Varenka; Munoz, Samuel E.; Schroeder, Sissel; Cao, Angelica; Bogdanovich, Taylor (2019-03-19). "Fecal stanols show simultaneous flooding and seasonal precipitation change correlate with Cahokia's population decline". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (12): 5461–5466. doi:10.1073/pnas.1809400116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6431169. PMID 30804191.

- ^ Jones, Terry L.; Schwitalla, Al (2008). "Archaeological perspectives on the effects of medieval drought in prehistoric California". Quaternary International. 188 (1): 41–58. Bibcode:2008QuInt.188...41J. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.07.007.

- ^ "Drought In West Linked To Warmer Temperatures". Earth Observatory News. 2004-10-07. Archived from the original on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Khim, B.; Yoon, Ho Il; Kang, Cheon Yun; Bahk, Jang Jun (2002). "Unstable Climate Oscillations during the Late Holocene in the Eastern Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula". Quaternary Research. 58 (3): 234. Bibcode:2002QuRes..58..234K. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2371. S2CID 129384061.

- ^ Lüning, Sebastian; Gałka, Mariusz; Vahrenholt, Fritz (2019-10-15). "The Medieval Climate Anomaly in Antarctica". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 532: 109251. Bibcode:2019PPP...532j9251L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109251. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Cobb, Kim M.; Chris Charles; Hai Cheng; R. Lawrence Edwards (July 8, 2003). "The Medieval Cool Period And The Little Warm Age In The Central Tropical Pacific? Fossil Coral Climate Records Of The Last Millennium". The Climate of the Holocene (ICCI) 2003. Archived from the original on August 25, 2004. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Rosenthal, Yair; Linsley, Braddock K.; Oppo, Delia W. (2013-11-01). "Pacific Ocean Heat Content During the Past 10,000 Years". Science. 342 (6158): 617–621. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..617R. doi:10.1126/science.1240837. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24179224. S2CID 140727975.

- ^ Fletcher, M-S.; Moreno, P.I. (16 July 2012). "Vegetation, climate and fire regime changes in the Andean region of southern Chile (38°S) covaried with centennial-scale climate anomalies in the tropical Pacific over the last 1500 years". Quaternary Science Reviews. 46: 46–56. Bibcode:2012QSRv...46...46F. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.04.016. hdl:10533/131338.

- ^ Ledru, M.-P.; Jomelli, V.; Samaniego, P.; Vuille, M.; Hidalgo, S.; Herrera, M.; Ceron, C. (2013). "The Medieval Climate Anomaly and the Little Ice Age in the eastern Ecuadorian Andes". Climate of the Past. 9 (1): 307–321. Bibcode:2013CliPa...9..307L. doi:10.5194/cp-9-307-2013.

- ^ Kellerhals, T.; Brütsch, S.; Sigl, M.; Knüsel, S.; Gäggeler, H. W.; Schwikowski, M. (2010). "Ammonium concentration in ice cores: A new proxy for regional temperature reconstruction?". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (D16): D16123. Bibcode:2010JGRD..11516123K. doi:10.1029/2009JD012603.

- ^ Adhikari, D. P.; Kumon, F. (2001). "Climatic changes during the past 1300 years as deduced from the sediments of Lake Nakatsuna, central Japan". Limnology. 2 (3): 157. doi:10.1007/s10201-001-8031-7. S2CID 20937188.

- ^ Yamada, Kazuyoshi; Kamite, Masaki; Saito-Kato, Megumi; Okuno, Mitsuru; Shinozuka, Yoshitsugu; Yasuda, Yoshinori (2010). "Late Holocene monsoonal-climate change inferred from Lakes Ni-no-Megata and San-no-Megata, northeastern Japan". Quaternary International. 220 (1–2): 122–132. Bibcode:2010QuInt.220..122Y. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.09.006.

- ^ Ge, Q.-S.; Zheng, J.-Y.; Hao, Z.-X.; Shao, X.-M.; Wang, Wei-Chyung; Luterbacher, Juerg (2010). "Temperature variation through 2000 years in China: An uncertainty analysis of reconstruction and regional difference". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (3): 03703. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..37.3703G. doi:10.1029/2009GL041281. S2CID 129457163.

- ^ Allen, Robert J. (1985). The Australasian Summer Monsoon, Teleconnections, and Flooding in the Lake Eyre Basin. Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, S.A. Branch. ISBN 978-0-909112-09-7.[page needed]

- ^ Wilson, A. T.; Hendy, C. H.; Reynolds, C. P. (1979). "Short-term climate change and New Zealand temperatures during the last millennium". Nature. 279 (5711): 315. Bibcode:1979Natur.279..315W. doi:10.1038/279315a0. S2CID 4302802.

- ^ Cook, Edward R.; Palmer, Jonathan G.; d'Arrigo, Rosanne D. (2002). "Evidence for a 'Medieval Warm Period' in a 1,100 year tree-ring reconstruction of past austral summer temperatures in New Zealand". Geophysical Research Letters. 29 (14): 12. Bibcode:2002GeoRL..29.1667C. doi:10.1029/2001GL014580. S2CID 34033855.

Further reading[]

- Hughes, Malcolm K.; Diaz, Henry F. (1994). "Was there a 'medieval warm period', and if so, where and when?" (PDF). Climatic Change. 26 (2–3): 109–42. Bibcode:1994ClCh...26..109H. doi:10.1007/BF01092410. S2CID 128680153.

- Fagan, Brian (2000). The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History, 1300–1850. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02272-4.

- Fagan, Brian (2009). The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781596913929.

- Lamb, Hubert (1995). Climate, History, and the Modern World: Second Edition. Routledge.

- Vinther, B.M.; Jones, P.D.; Briffa, K.R.; Clausen, H.B.; Andersen, K.K.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Johnsen, S.J. (2010). "Climatic signals in multiple highly resolved stable isotope records from Greenland". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (3–4): 522–38. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29..522V. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.11.002.

- Staff members at NOAA Paleoclimatology (19 May 2000). The "Medieval Warm Period". A Paleo Perspective...on Global Warming. NOAA Paleoclimatology.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medieval Warm Period. |

- HistoricalClimatology.com, further links, resources, and relevant news, updated 2016

- Climate History Network

- The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period at American Geophysical Union

- 950 establishments

- 1250 disestablishments

- History of climate variability and change

- 10th century

- 11th century

- 12th century

- 13th century

- Holocene