Mediterranean Lingua Franca

| Mediterranean Lingua Franca | |

|---|---|

| sabir | |

| Region | Mediterranean Basin (esp. Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Lebanon, Greece, Cyprus) |

| Extinct | 19th century |

Pidgin, Romance based

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | none |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pml |

| Glottolog | ling1242 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-c |

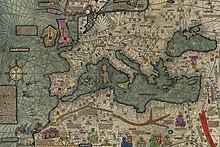

The Mediterranean Lingua Franca or Sabir was a pidgin language used as a lingua franca in the Mediterranean Basin from the 11th to the 19th centuries.[1]

History[]

Lingua franca means literally "language of the Franks" in Late Latin, and originally referred specifically to the language that was used around the Eastern Mediterranean Sea as the main language of commerce.[2] However, the term "Franks" was actually applied to all Western Europeans during the late Byzantine Period.[3][4] Later, the meaning of lingua franca expanded to mean any bridge language. Its other name in the Mediterranean area was Sabir, a term cognate of saber—“to know”, in most Iberian languages—and of Italian sapere and French savoir.

Based mostly on Northern Italian languages (mainly Venetian and Genoese) and secondarily from Occitano-Romance languages (Catalan and Occitan) in the western Mediterranean area at first,[5] it later came to have more Spanish and Portuguese elements, especially on the Barbary coast (today referred to as the Maghreb). Sabir also borrowed from Berber, Turkish, French, Greek and Arabic. This mixed language was used widely for commerce and diplomacy and was also current among slaves of the bagnio, Barbary pirates and European renegades in pre-colonial Algiers. Historically the first to use it were the Genoese and Venetian trading colonies in the eastern Mediterranean after the year 1000.

As the use of Lingua Franca spread in the Mediterranean, dialectal fragmentation emerged, the main difference being more use of Italian and Provençal vocabulary in the Middle East, while Ibero-Romance lexical material dominated in the Maghreb. After France became the dominant power in the latter area in the 19th century, Algerian Lingua Franca was heavily gallicised (to the extent that locals are reported having believed that they spoke French when conversing in Lingua Franca with the Frenchmen, who in turn thought they were speaking Arabic), and this version of the language was spoken into the nineteen hundreds .... Algerian French was indeed a dialect of French, although Lingua Franca certainly had had an influence on it. ... Lingua Franca also seems to have affected other languages. Eritrean Pidgin Italian, for instance, displayed some remarkable similarities with it, in particular the use of Italian participles as past or perfective markers. It seems reasonable to assume that these similarities have been transmitted through Italian stereotypes.[6]

Hugo Schuchardt (1842–1927) was the first scholar to investigate the Lingua Franca systematically. According to the monogenetic theory of the origin of pidgins he developed, Lingua Franca was known by Mediterranean sailors including the Portuguese. When Portuguese started exploring the seas of Africa, America, Asia and Oceania, they tried to communicate with the natives by mixing a Portuguese-influenced version of Lingua Franca with the local languages. When English or French ships came to compete with the Portuguese, the crews tried to learn this "broken Portuguese". Through a process of relexification, the Lingua Franca and Portuguese lexicon was substituted by the languages of the peoples in contact.

This theory is one way of explaining the similarities between most of the European-based pidgins and creole languages, such as Tok Pisin, Papiamento, Sranan Tongo, Krio, and Chinese Pidgin English. These languages use forms similar to sabir for 'to know' and piquenho for "children".

Lingua Franca left traces in present and Polari. There are traces even in geographical names, such as Cape Guardafui (that literally means "Cape Look and Escape" in Lingua Franca and ancient Italian).

Example of "Sabir"[]

An example of Sabir is found in Molière's comedy Le Bourgeois gentilhomme.[7] At the start of the "Turkish ceremony", the Mufti enters singing the following words:

Se ti sabir

Ti respondir

Se non sabir

Tazir, tazir

Mi star Mufti:

Ti qui star ti?

Non intendir:

Tazir, tazir.

A comparison of the Sabir version with the same text in each of similar languages, first a word-for-word substitution according to the rules of Sabir grammar and then a translation inflected according to the rules of the similar language's grammar, can be seen below:

| Sabir | Italian | Spanish | Catalan | Galician | Portuguese | Occitan (Provençal) | French | Latin | English | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Se ti sabir |

Se tu sapere |

Se sai |

Si tú saber |

Si sabes, |

Si tu saber |

Si ho saps |

Se ti saber |

Se sabes |

Se tu saber |

Se sabes |

Se tu saber |

Se sabes |

Si toi savoir |

Si tu sais |

Si tu scire |

Si scis |

If you know |

The Italian, Spanish, Catalan, Galician, Portuguese, Provençal, French, and Latin versions are not correct grammatically, as they use the infinitive rather than inflected verb forms, but the Sabir form is obviously derived from the infinitive in those languages. There are also differences in the particular Romance copula, with Sabir using a derivative of stare rather than of esse. The correct version for each language is given in italics.

See also[]

- African Romance

- Mozarabic language

- Lingua Franca Nova

Notes[]

- ^ Bruni, Francesco. "Storia della Lingua Italiana: Gli scambi linguistici nel Mediterraneo e la lingua franca" [History of the Italian Language: Linguistic exchanges in the Mediterranean and the lingua franca] (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ "lingua franca". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ Lexico Triantaphyllide online dictionary , Greek Language Center (Kentro Hellenikes Glossas), lemma Franc (Φράγκος Phrankos) , Lexico tes Neas Hellseenikes Glossas, G.Babiniotes, Kentro Lexikologias(Legicology Center) LTD Publications. Komvos.edu.gr. 2002. ISBN 960-86190-1-7. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

Franc and (prefix) franco- (Φράγκος Phrankos and φράγκο- phranko-

- ^ Weekley, Ernest (1921). "frank". An etymological dictionary of modern English. London. p. 595. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Castellanos, Carles (2007). "La lingua franca, una revolució lingüística mediterrània amb empremta catalana" (PDF) (in Catalan). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ (2005). (ed.). "Foreword to A Glossary of Lingua Franca" (5th ed.). Milwaukee, WI, United States. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ La Cérémonie turque with a translation in English Archived 2021-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography[]

- Dakhlia, Jocelyne, Lingua Franca – Histoire d'une langue métisse en Méditerranée, Actes Sud, 2008, ISBN 2-7427-8077-7

- John A. Holm, Pidgins and Creoles, Cambridge University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-521-35940-6, p. 607

- Henry Romanos Kahane, The Lingua Franca in the Levant: Turkish Nautical Terms of Italian and Greek Origin, University of Illinois, 1958

- Hugo Schuchardt, "The Lingua Franca". Pidgin and Creole languages: selected essays by Hugo Schuchardt (edited and translated by Glenn G. Gilbert), Cambridge University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-521-22789-5.

External links[]

- Dictionnaire de la Langue Franque ou Petit Mauresque, 1830. (In French)

- A Glossary of Lingua Franca, fifth edition, 2005, . It includes articles about the language from various authors and sample texts.

- Tales in Sabir from Algeria

- Lingua franca in the Mediterranean (Google book)

- Pidgins and creoles

- Languages of Algeria

- Languages of Tunisia

- Languages of Sicily

- Extinct languages of Africa

- Extinct languages of Europe

- Italian language

- Romance languages

- History of the Mediterranean

- Languages attested from the 11th century

- Languages extinct in the 19th century