Michael (archangel)

Saint Michael | |

|---|---|

Saint Michael in The Fall of the Rebel Angels by Luca Giordano | |

| Archangel, Prince of Heavenly Host | |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints Judaism Islam |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Archangel; Treading on a dragon; carrying a banner, scales, sword, and weighing souls |

| Patronage | Protector of the Jewish people,[1] Guardian of the Catholic Church,[2] Vatican City,[3][4][failed verification] sickness, police officers, military[5] |

Michael (Hebrew: [mixaˈʔel]; Hebrew: מִיכָאֵל, romanized: Mīḳā'ēl, lit. 'Who is like El?'; Greek: Μιχαήλ, romanized: Mikhaḗl; Latin: Michahel; Coptic: ⲙⲓⲭⲁⲏⲗ; Arabic: ميخائيل ، مِيكَالَ ، ميكائيل, romanized: Mīkā'īl, Mīkāl or Mīkhā'īl)[6] is an archangel in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran systems of faith, he is called Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint Michael. In the Oriental Orthodox faith he is called Saint Michael the Taxiarch.[7][8] In many Protestant denominations, he is referred to as Archangel Michael.

Michael is mentioned three times in the Book of Daniel. The idea that Michael was the advocate of the Jews became so prevalent that, in spite of the rabbinical prohibition against appealing to angels as intermediaries between God and his people, Michael came to occupy a certain place in the Jewish liturgy.

In the New Testament, Michael leads God's armies against Satan's forces in the Book of Revelation, where during the war in heaven he defeats Satan. In the Epistle of Jude, Michael is specifically referred to as "the archangel Michael". Sanctuaries to Michael were built by Christians in the 4th century, when he was first seen as a healing angel. Over time his role became one of a protector and the leader of the army of God against the forces of evil.

Scriptural references[]

Hebrew Bible[]

Michael is mentioned three times in the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament), all in the Book of Daniel. The prophet Daniel has a vision after having undergone a period of fasting. Daniel 10:13–21 describes Daniel's vision of an angel who identifies Michael as the protector of Israelites.[9] At Daniel 12:1, Daniel is informed that Michael will arise during the "time of the end".[10]

New Testament[]

The Book of Revelation (12:7–9) describes a war in heaven in which Michael, being stronger, defeats Satan.[11] After the conflict, Satan is thrown to Earth along with the fallen angels, where he ("that ancient serpent called the devil") still tries to "lead the whole world astray".[11]

In the Epistle of Jude 1:9, Michael is referred to as an "archangel" when he again confronts Satan.[12]

Quran[]

Michael (Arabic: مِيكَىٰل Mīkāʾl,[Quran 2:98][13] or مِيكَائِيل Mīkāʾīl), is one of the two archangels mentioned in the Quran, alongside Gabriel. However he is mentioned by name only once, in 2:98:

Whoever is an enemy to God, and His angels and His messengers, and Gabriel and Michael: [Know] then indeed [that] God is an enemy to the deniers [of faith].

According to Quranic exegesis, Michael was one of three angels who visited Abraham in order to inform him of the birth of Isaac in 51:24-30.[14]

Religious faiths[]

Judaism[]

According to rabbinic Jewish tradition, Michael acted as the advocate of Israel, and sometimes had to fight with the princes of the other nations (cf. 10:13) and particularly with the angel Samael, Israel's accuser. Michael's enmity against Samael dates from the time when the latter was thrown down from heaven. Samael took hold of the wings of Michael, whom he wished to bring down with him in his fall; but Michael was saved by God.[15][16] Michael said, "May The Lord rebuke you" to Satan for attempting to claim the body of Moses.[17]

The idea that Michael was the advocate of the Jews became so prevalent[where?] that in spite of the rabbinical prohibition against appealing to angels as intermediaries between God and his people, Michael came to occupy a certain place in the Jewish liturgy: "When a man is in need he must pray directly to God, and neither to Michael nor to Gabriel."[18] Two prayers were written beseeching him as the prince of mercy to intercede in favor of Israel: one composed by Byzantine Jew (c. 570 – c. 640), and the other by Judah ben Samuel he-Hasid (1150 – 22 February 1217), a leader of the Chassidei Ashkenaz in Bavaria. But appeal to Michael seems to have been more common in ancient times[where?][when?]. Jeremiah addresses a prayer to him.[19]

The rabbis declare that Michael entered upon his role of defender at the time of the biblical patriarchs. Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob said that Michael rescued Abraham from the furnace into which he had been thrown by Nimrod (Midrash Genesis Rabbah xliv. 16). It is claimed that it was Michael, the "one that had escaped" (Genesis 14:13), who told Abraham that Lot had been taken captive (Midrash Pirke R. El.), and who protected Sarah from being defiled by Abimelech.

It is also said that Michael prevented Isaac from being sacrificed by his father by substituting a ram in his place. He saved Jacob, while yet in his mother's womb, from being killed by Samael.[20] Later Michael prevented Laban from harming Jacob.(Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, xxxvi).

The midrash Exodus Rabbah holds that Michael exercised his function of advocate of Israel at the time of the Exodus also. Michael is also said to have destroyed the army of Sennacherib.[21]

Christianity[]

Early Christian views and devotions[]

Michael was venerated as a healer in Phrygia (modern-day Turkey).[22]

The earliest and most famous sanctuary to Michael in the ancient Near East was also associated with healing waters. It was the Michaelion built in the early 4th century by Emperor Constantine at Chalcedon, on the site of an earlier temple called Sosthenion.[23]

Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–320 – 403) referred in his Coptic-Arabic Hexaemeron to Michael as a replacement of Satan. Accordingly, after Satan fell, Michael was appointed to the function Satan served when he was still one of the noble angels.[24]

A painting of the Archangel slaying a serpent became a major art piece at the Michaelion after Constantine defeated Licinius near there in 324. This contributed to the standard iconography that developed of Archangel Michael as a warrior saint slaying a dragon.[23] The Michaelion was a magnificent church and in time became a model for hundreds of other churches in Eastern Christianity; these spread devotions to the Archangel.[25]

In the 4th century, Saint Basil the Great's homily (De Angelis) placed Saint Michael over all the angels. He was called "Archangel" because he heralds other angels, the title Ἀρχαγγέλος (archangelos) being used of him in Jude 1:9.[22] Into the 6th century, the view of Michael as a healer continued in Rome; after a plague, the sick slept at night in the church of Castel Sant'Angelo (dedicated to him for saving Rome), waiting for his manifestation.[26]

In the 6th century, the growth of devotions to Michael in the Western Church was expressed by the feasts dedicated to him, as recorded in the Leonine Sacramentary. The 7th-century Gelasian Sacramentary included the feast "S. Michaelis Archangeli", as did the 8th-century Gregorian Sacramentary. Some of these documents refer to a Basilica Archangeli (no longer extant) on via Salaria in Rome.[22]

The angelology of Pseudo-Dionysius, which was widely read as of the 6th century, gave Michael a rank in the celestial hierarchy. Later, in the 13th century, others such as Bonaventure believed that he is the prince of the Seraphim, the first of the nine angelic orders. According to Thomas Aquinas (Summa Ia. 113.3), he is the Prince of the last and lowest choir, the Angels.[22]

Catholicism[]

Catholics often refer to Michael as "Holy Michael, the Archangel"[27] or "Saint Michael", a title that does not indicate canonisation. He is generally referred to in Christian litanies as "Saint Michael", as in the Litany of the Saints. In the shortened version of this litany used in the Easter Vigil, he alone of the angels and archangels is mentioned by name, omitting saints Gabriel and Raphael.[28]

In Roman Catholic teachings, Saint Michael has four main roles or offices.[22] His first role is the leader of the Army of God and the leader of heaven's forces in their triumph over the powers of hell.[29] He is viewed as the angelic model for the virtues of the spiritual warrior, with the conflict against evil at times viewed as the battle within.[30]

The second and third roles of Michael in Catholic teachings deal with death. In his second role, Michael is the angel of death, carrying the souls of all the deceased to heaven. In this role Michael descends at the hour of death, and gives each soul the chance to redeem itself before passing; thus consternating the devil and his minions. Catholic prayers often refer to this role of Michael. In his third role, he weighs souls in his perfectly balanced scales. For this reason, Michael is often depicted holding scales.[31]

In his fourth role, Saint Michael, the special patron of the Chosen People in the Old Testament, is also the guardian of the Church. Saint Michael was revered by the military orders of knights during the Middle Ages. The names of villages around the Bay of Biscay express that history. This role also was why he was considered the patron saint of a number of cities and countries.[32][33]

Roman Catholicism includes traditions such as the Prayer to Saint Michael, which specifically asks for the faithful to be "defended" by the saint.[34][35][36] The Chaplet of Saint Michael consists of nine salutations, one for each choir of angels.[37][38]

Saint Michael the Archangel prayer[]

Blessed Michael, archangel,

defend us in the hour of conflict.

Be our safeguard against the wickedness and snares of the devil

(may God restrain him, we humbly pray):

and do thou, O Prince of the heavenly host,

by the power of God thrust Satan down to hell

and with him those other wicked spirits

who wander through the world for the ruin of souls.

Amen.[39]

Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy[]

The Eastern Orthodox accord Michael the title Archistrategos, or "Supreme Commander of the Heavenly Hosts".[40] The Eastern Orthodox pray to their guardian angels and above all to Michael and Gabriel.[41]

The Eastern Orthodox have always had strong devotions to angels. In contemporary times they are referred to by the term of "Bodiless Powers".[42] A number of feasts dedicated to Archangel Michael are celebrated by the Eastern Orthodox throughout the year.[42]

Archangel Michael is mentioned in a number of Eastern Orthodox hymns and prayer, and his icons are widely used within Eastern Orthodox churches.[43] In many Eastern Orthodox icons, Christ is accompanied by a number of angels, Michael being a predominant figure among them.[43]

In Russia, many monasteries, cathedrals, court and merchant churches are dedicated to the Chief Commander Michael; most Russian cities have a church or chapel dedicated to the Archangel Michael.[44][45]

While in the Serbian Orthodox Church Saint Sava has a special role as the establisher of its autocephaly and the largest Belgrade church is devoted to him, the capital Belgrade's Orthodox cathedral, the see church of the patriarch, is devoted to Archangel Michael (in Serbian: Арханђел Михаило / Arhanđel Mihailo).

The place of Michael in the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria is as a saintly intercessor. He is the one who presents to God the prayers of the just, who accompanies the souls of the dead to heaven, who defeats the devil. He is celebrated liturgically on the 12th of each Coptic month.[46] In Alexandria, a church was dedicated to him in the early fourth century on the 12th of the month of Paoni. The 12th of the month of Hathor is the celebration of Michael's appointment in heaven, where Michael became the chief of the angels.[47]

Protestant views[]

Some Protestant denominations recognize Michael as an archangel. Within Protestantism, the Anglican and Methodist tradition recognizes four angels as archangels: Michael, Raphael, Gabriel, and Uriel.[48][49] The American evangelist Billy Graham wrote that in Sacred Scripture, there is only one individual explicitly described as an archangel—Michael—in Jude 1:9.[50][51]

Citing Hengstenberg, John A. Lees, in International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, states: "The earlier Protestant scholars usually identified Michael with the pre-incarnate Christ, finding support for their view, not only in the juxtaposition of the 'child' and the archangel in Rev 12:1–17, but also in the attributes ascribed to him in Daniel."[52]

Such scholars include but are not limited to:

- Martin Luther[53][54]

- Hengstenberg with others[55][56][57]

- Dr. W. L. Alexander [in Kitto], Prof. Douglas [in Fairbairn][58]

- Jacobus Ode, Campegius Vitringa, Sr.[59][60][61]

- Philip Melanchthon, Broughton, Junius, Calvin, Hävernick[62]

- Polanus, Genevens, Oecolampadius & others,[63] Adam Clarke[64]

- Samuel Horsley[65][66]

- Cloppenburgh, Vogelsangius, Pierce and others (Horsely)[67]

- John (Jean) Calvin[68][69]

- Isaac Watts, John Bunyan, Brown's Dictionary, James Wood's Spiritual Dictionary[70]

- and many others[71]

- for even before them, the Jewish commentators, such as Wetstein, Surenhusius, etc.[72]

In the 19th Century, Charles Haddon Spurgeon[73][74] stated that Jesus is "the true Michael" [75][76] and “the only Archangel”,[77] and that he is God the Son, and co-equal to the Father.[73]

Within Anglicanism, the controversial bishop Robert Clayton (died 1758) proposed that Michael was the Logos and Gabriel the Holy Spirit.[78] Controversy over Clayton's views led the government to order his prosecution, but he died before his scheduled examination.[79][80]

Michael continues to be recognized[specify][vague][who?]among Protestants by key churches dedicated to him, e.g., St. Michaelis Church, Hamburg and St. Michael's Church, Hildesheim, each of which is of the Lutheran Church and has appeared in the Bundesländer series of €2 commemorative coins for 2008 and 2014 respectively.

In Bach's time, the annual feast of Michael and All the Angels on 29 September was regularly celebrated with a festive service, for which Bach composed several cantatas, for example the chorale cantata Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir, BWV 130 in 1724, Es erhub sich ein Streit, BWV 19, in 1726 and Man singet mit Freuden vom Sieg, BWV 149, in 1728 or 1729.

Seventh-day Adventists[]

Seventh-day Adventists believe that "Michael" is but one of the many titles applied to the Son of God, the second person of the Godhead. According to Adventists, such a view does not in any way conflict with the belief in his full deity and eternal preexistence, nor does it in the least disparage his person and work.[81] According to Adventist theology, Michael was considered the "eternal Word", and not a created being or created angel, and the one by whom all things were created. The Word was then born incarnate as Jesus.[82]

They believe that name "Michael" signifies "One Who Is Like God" and that as the "Archangel" or "chief or head of the angels" he led the angels and thus the statement in Revelation 12:7–9 identifies Jesus as Michael.[83]

In the Seventh-day Adventist view, the statement in some translations of 1 Thessalonians 4:13–18 and John 5:25–29 confirm that Jesus and Michael are the same.[84]

Jehovah's Witnesses[]

Jehovah's Witnesses believe Michael to be another name for Jesus in heaven, in his pre-human and post-resurrection existence.[85] They say the definite article at Jude 9—referring to "Michael the archangel"—identifies Michael as the only archangel. They consider Michael to be synonymous with Christ, described at 1 Thessalonians 4:16 as descending "with a cry of command, with the voice of an archangel, and with the sound of the trumpet".[86][87][88]

They believe the prominent roles assigned to Michael at Daniel 12:1, Revelation 12:7, Revelation 19:14, and Revelation 16 are identical to Jesus' roles, being the one chosen to lead God's people and as the only one who "stands up", identifying the two as the same spirit being. Because they identify Michael with Jesus, he is therefore considered the first and greatest of all God's heavenly sons, God's chief messenger, who takes the lead in vindicating God's sovereignty, sanctifying his name, fighting the wicked forces of Satan and protecting God's covenant people on earth.[89] Jehovah's Witnesses also identify Michael with the "Angel of the Lord" who led and protected the Israelites in the wilderness.[90]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints[]

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known informally as Latter-day Saints or Mormons) believe that Michael is Adam, the Ancient of Days (Dan. 7), a prince, and the patriarch of the human family. They also hold that Michael assisted Jehovah (the pre-mortal form of Jesus) in the creation of the world under the direction of God the Father (Elohim); under the direction of the Father, Michael also cast Satan out of heaven.[91][92][93][94]

Islam[]

In Islam, Michael, or Mīkāʾīl,[95] is the angel said to effectuate God’s providence as well as natural phenomena, such as rain.[96] He is one of the four archangels along with Jibrāʾīl (Gabriel, whom he is often paired with), ʾIsrāfīl (trumpeter angel) and ʿAzrāʾīl (angel of death).[97] He is mentioned in Quran 2:98 along with Gabriel, whom God supports against the Medinan Jews who, according to at-Tabari,[98] were critical of and antagonistic toward Gabriel and saw Mīkāʾīl as their advocate (Daniel 10:13–21).

Michael in Islam is tasked with providing nourishment for bodies and souls and is also responsible for universal or environmental events, and is often depicted as the archangel of mercy. He is said[by whom?] to be friendly, asking God for mercy toward humans and is, according to Muslim legends, one of the first to obey God's orders to bow before Adam.[99][96] He is also responsible for the rewards doled out to good persons in this life. From the tears of Michael, angels are created as his helpers.[100]

In a version of a hadith by an-Nasāʾi, Muhammad is quoted as saying that Gabriel and Michael came to him, and when Gabriel had sat down at his right and Michael at his left, Gabriel told him to recite the Qurʾān in one mode, and Michael told him to ask more, till he reached seven modes, each mode being sufficiently health-giving.[101] According to another hadith in Sahih Muslim, Michael, along with Gabriel both dressed in white, were reported to have accompanied Muhammad on the day of the Battle of Uhud.[102]

In Shia Islam, in Dua Umm Dawood, a supplication reportedly handed down by the 6th Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq, the reciter sends blessing upon Michael (with his name spelled as Mīkā'īl):[103][104]

O Allah! Bestow your blessing on Michael-angel of Your mercy and created for kindness and seeker of pardon for and supporter of the obedient people.

Michael appears in the creation narrative of Adam. Accordingly, he was sent to bring a handful of earth, but the Earth did not yield a piece of itself, some of which will burn. This is articulated by Al-Tha'labi, whose narrative states that God tells Earth that some will obey him and others will not.[105]

Baha'i Faith[]

The archangel Michael seems to have never been mentioned publicly by Baha'u'llah, 'Abdu'l-Baha, Shoghi Effendi, or even the Universal House of Justice. However, in Baha'i publishing about the interpretation of the Book of Revelation from the New Testament, Baha'is have claimed that Baha'u'llah was ""one of the chief princes" of Persia"[106][107] foretold as Michael who would win "final victory over the dragon". Or, Michael, "One like God", is thought to be Baha'u'llah, as archangel Michael is thought to be an emanation of Hod or "glory" in Jewish Mysticism[108] - because "Baha'u'llah" means splendor or glory of God.

Esoteric beliefs[]

The French occultist Eliphas Levi, the German philosopher Franz von Baader, and the Theosophist Louis Claude de St. Martin spoke of 1879 as the year in which Michael overcame the dragon. In 1917, Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy, similarly stated, "in 1879, in November, a momentous event took place, a battle of the Powers of Darkness against the Powers of Light, ending in the image of Michael overcoming the Dragon".[109]

Archangel Michael was also mentioned in the older Greek Magical Papyri (circa 2nd century BC–400 AD), only in these set of texts he goes under the title of a deity.[110] In Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's Three Books of Occult Philosophy and some other sources, Michael is always mentioned as ruling over the planet Mercury,[111] however, in other sources such as the Heptameron by pseudo-Pietro d'Abano, Michael rules over the Sun,[112] and the fourth of the seven Heavens in Judaism, which is named Machon or Machen.[113] Instead, the Archangel Raphael rules over Mercury (and the second Heaven, which is listed as Raquie).[114] The switch between solar and mercurial associations for Michael and Raphael happens all throughout the Solomonic grimoire tradition, changing practically from book to book depending on the influences and derivations of previous grimoires each is based on. Depending on the time and region of each manuscript, different correspondences may have been passed down, and neither association is ultimately more legitimate than the other.

Feasts[]

In the General Roman Calendar, the Anglican Calendar of Saints, and the Lutheran Calendar of Saints, the archangel's feast is celebrated on Michaelmas Day, 29 September. The day is also considered the feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, in the General Roman Calendar and the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels according to the Church of England.[115]

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Saint Michael's principal feast day is 8 November (those that use the Julian calendar celebrate it on what in the Gregorian calendar is now 21 November), honouring him along with the rest of the "Bodiless Powers of Heaven" (i.e. angels) as their Supreme Commander, and the Miracle at Chonae is commemorated on 6 September.[116][117]

In the calendar of the Church of England diocese of Truro, 8 May is the feast of St. Michael, Protector of Cornwall. The archangel Michael is one of the three patron saints of Cornwall.[118] The feast of the Appearing of S. Michael the Archangel is observed by Anglo-Catholics on 8 May.[119] From medieval times until 1960 it was also observed on that day in the Roman Catholic Church; the feast commemorates the archangel's apparition on Mount Gargano in Italy.[120]

In the Coptic Orthodox Church, the main feast day in 12 Hathor and 12 Paoni, and he is celebrated liturgically on the 12th of each Coptic month.

Patronages and orders[]

In late medieval Christianity, Michael, together with Saint George, became the patron saint of chivalry and is now also considered the patron saint of police officers, paramedics and the military.[33][121]

Since the victorious Battle of Lechfeld against the Hungarians in 955, Michael was the patron saint of the Holy Roman Empire and still is the patron saint of modern Germany and other German-speaking regions formerly covered by the realm.

In mid to late 15th century, France was one of only four courts in Western Christendom without an order of knighthood.[122] Later in the 15th century, Jean Molinet glorified the primordial feat of arms of the archangel as "the first deed of knighthood and chivalrous prowess that was ever achieved."[123] Thus Michael was the natural patron of the first chivalric order of France, the Order of Saint Michael of 1469.[122] In the British honours system, a chivalric order founded in 1818 is also named for these two saints, the Order of St Michael and St George.[124]

Prior to 1878, the Scapular of St. Michael the Archangel could be worn as part of a Roman Catholic Archconfraternity. Presently, enrollment is authorized as this holy scapular remains as one of the 18 approved by the Church.

Apart from his being a patron of warriors, the sick and the suffering also consider Archangel Michael their patron saint.[125] Based on the legend of his 8th-century apparition at Mont-Saint-Michel, France, the Archangel is the patron of mariners in this famous sanctuary.[22] After the evangelisation of Germany, where mountains were often dedicated to pagan gods, Christians placed many mountains under the patronage of the Archangel, and numerous mountain chapels of St. Michael appeared all over Germany.[22]

Similarly, the Sanctuary of St. Michel (San Migel Aralarkoa), the oldest Christian building in Navarre (Spain), lies at the top of a hill on the Aralar Range, and harbours Carolingian remains. St. Michel is an ancient devotion of Navarre and eastern Gipuzkoa, revered by the Basques, shrouded in legend, and held as a champion against paganism and heresy. It came to symbolize the defense of Catholicism, as well as Basque tradition and values during the early 20th century.[126]

He has been the patron saint of Brussels since the Middle Ages.[127] The city of Arkhangelsk in Russia is named for the Archangel. Ukraine and its capital Kyiv also consider Michael their patron saint and protector.[128] In Linlithgow, Scotland, St. Michael has been the patron saint of the town since the 13th century, with being originally constructed in 1134. Since the 14th century, Saint Michael has been the patron saint of Dumfries in Scotland, where a church dedicated to him was built at the southern end of the town, on a mound overlooking the River Nith.[129]

An Anglican sisterhood dedicated to Saint Michael under the title of the Community of St Michael and All Angels was founded in 1851.[130] The Congregation of Saint Michael the Archangel (CSMA), also known as the Michaelite Fathers, is a religious order of the Roman Catholic Church founded in 1897. The Canons Regular of the Order of St Michael the Archangel (OSM) are an Order of professed religious within the Anglican Church in North America, the North American component of the Anglican realignment movement.[131]

In the United States military Saint Michael is considered to be a patron of paratroopers and, in particular, the 82nd Airborne Division.[132] One of the first battles where the unit first was combat christened is the Battle of Saint-Mihiel during World War I.

The beret insignia of The 2nd Foreign Legion Parachute Regiment (French: 2 e Régiment étranger de parachutistes, 2 e REP) is a winged arm grasping a dagger, representing Saint Michael. [133]

Legends[]

Judaism[]

There is a legend which seems to be of Jewish origin, and which was adopted by the Copts, to the effect that Michael was first sent by God to bring Nebuchadnezzar (c. 600 BC) against Jerusalem, and that Michael was afterward very active in freeing his nation from Babylonian captivity.[134] According to midrash Genesis Rabbah, Michael saved Hananiah and his companions from the Fiery furnace though the verse states that the person in the fire was the Son of God (not an angel).[135] Michael was active in the time of Esther: "The more Haman accused Israel on earth, the more Michael defended Israel in heaven".[136] It was Michael who reminded Ahasuerus that he was Mordecai's debtor;[137] and there is a legend that Michael appeared to the high priest Hyrcanus, promising him assistance.[138]

According to Legends of the Jews, archangel Michael was the chief of a band of angels who questioned God's decision to create man on Earth; a deeper analysis about Archangel Michael's action here is that Archangel Michael could have also questioned God as to why he did not kill Satan and his rebel horde of djinns/demons the minute Adam and Eve were created, thus removing the parable of evil and the question of the Garden of Eden.[139] Regardless, the entire band of angels, except for Michael, was then consumed by fire.[139]

Christianity[]

The Orthodox Church celebrates the Miracle at Chonae on September 6.[140] The pious legend surrounding the event states that John the Apostle, when preaching nearby, foretold the appearance of Michael at Cheretopa near Lake Salda, where a healing spring appeared soon after the Apostle left; in gratitude for the healing of his daughter, one pilgrim built a church on the site.[141] Local pagans, who are described as jealous of the healing power of the spring and the church, attempt to drown the church by redirecting the river, but the Archangel, "in the likeness of a column of fire", split the bedrock to open up a new bed for the stream, directing the flow away from the church.[142] The legend is supposed to have predated the actual events, but the 5th – 7th-century texts that refer to the miracle at Chonae formed the basis of specific paradigms for "properly approaching" angelic intermediaries for more effective prayers within the Christian culture.[143]

There is a late-5th-century legend in Cornwall, UK that the Archangel appeared to fishermen on St Michael's Mount.[144] According to author Richard Freeman Johnson, this legend is likely a nationalistic twist to a myth.[144] Cornish legends also hold that the mount itself was constructed by giants[145] and that King Arthur battled a giant there.[146]

The legend of the apparition of the Archangel at around 490 AD at a secluded hilltop cave on Monte Gargano in Italy gained a following among the Lombards in the immediate period thereafter, and by the 8th century, pilgrims arrived from as far away as England.[147] The Tridentine Calendar included a feast of the apparition on 8 May, the date of the 663 victory over the Greek Neapolitans that the Lombards of Manfredonia attributed to Saint Michael.[22] The feast remained in the Roman liturgical calendar until removed in the revision of Pope John XXIII. The Sanctuary of Monte Sant'Angelo at Gargano is a major Catholic pilgrimage site.

According to Roman legends, Archangel Michael appeared with a sword over the mausoleum of Hadrian while a devastating plague persisted in Rome, in apparent answer to the prayers of Pope Gregory I the Great (c. 590–604) that the plague should cease. After the plague ended, in honor of the occasion, the pope called the mausoleum "Castel Sant'Angelo" (Castle of the Holy Angel), the name by which it is still known.[26]

According to Norman legend, Michael is said to have appeared to St Aubert, Bishop of Avranches, in 708, giving instruction to build a church on the rocky islet now known as Mont Saint-Michel.[148][149][150] In 960 the Duke of Normandy commissioned a Benedictine abbey on the mount, and it remains a major pilgrimage site.[150]

A Portuguese Carmelite nun, Antónia d'Astónaco, reported an apparition and private revelation of the Archangel Michael who had told to this devoted Servant of God, in 1751, that he would like to be honored, and God glorified, by the praying of nine special invocations. These nine invocations correspond to invocations to the nine choirs of angels and origins the famous Chaplet of Saint Michael. This private revelation and prayers were approved by Pope Pius IX in 1851.[151][152]

From 1961 to 1965, four young schoolgirls had reported several apparitions of Archangel Michael in the small village of Garabandal, Spain. At Garabandal, the apparitions of the Archangel Michael were mainly reported as announcing the arrivals of the Virgin Mary. The Catholic Church has neither approved nor condemned the Garabandal apparitions.[153]

Art and literature[]

In literature[]

In the English epic poem Paradise Lost by John Milton, Michael commands the army of angels loyal to God against the rebel forces of Satan. Armed with a sword from God's armory, he bests Satan in personal combat, wounding his side.[154]

In Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's translation of The Golden Legend, Michael is one of the angels of the seven planets. He is the angel of Mercury.[155]

Music[]

Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Praelium Michaelis Archangeli factum in coelo cum dracone, H.410, oratorio for soloists, double chorus, strings and continuo. (1683)

Artistic depictions[]

In Christian art, Archangel Michael may be depicted alone or with other angels such as Gabriel. Some depictions with Gabriel date back to the 8th century, e.g. the stone casket at Notre Dame de Mortain church in France.[156]

The widely reproduced image of Our Mother of Perpetual Help, an icon of the Cretan school, depicts Michael on the left carrying the lance and sponge of the crucifixion of Jesus, with Gabriel on the right side of Mary and Jesus.[157]

In many depictions, Michael is represented as an angelic warrior, fully armed with helmet, sword, and shield.[22] The shield may bear the Latin inscription Quis ut Deus or the Greek inscription Christos Dikaios Krites or its initials.[158] He may be standing over a serpent, a dragon, or the defeated figure of Satan, whom he sometimes pierces with a lance.[22] The iconography of Michael slaying a serpent goes back to the early 4th century, when Emperor Constantine defeated Licinius at the Battle of Adrianople in 324 AD, not far from the Michaelion, a church dedicated to Archangel Michael.[23]

Constantine felt that Licinius was an agent of Satan and associated him with the serpent described in the Book of Revelation (12:9).[159] After the victory, Constantine commissioned a depiction of himself and his sons slaying Licinius represented as a serpent – a symbolism borrowed from the Christian teachings on the Archangel to whom he attributed the victory. A similar painting, this time with the Archangel Michael himself slaying a serpent, then became a major art piece at the Michaelion and eventually lead to the standard iconography of Archangel Michael as a warrior saint.[23]

In other depictions, Michael may be holding a pair of scales in which he weighs the souls of the departed and may hold the book of life (as in the Book of Revelation), to show that he takes part in the judgment.[156] However, this form of depiction is less common than the slaying of the dragon.[156] Michelangelo depicted this scene on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel.[160]

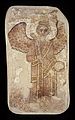

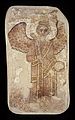

In Byzantine art, Michael was often shown as a princely court dignitary rather than a warrior who battled Satan or with scales for weighing souls on the Day of Judgement.[161]

Archangel Michael on a 9th-century Makurian mural

Andrei Rublev's standalone depiction c. 1408

Michael (left) with archangels Raphael and Gabriel, by Botticini, 1470

Weighing souls on Judgement Day by Hans Memling, 15th century

Michael defeating the fallen angels, by Luca Giordano c. 1660–65

Bronze statue of Archangel Michael, standing on top of the Castel Sant'Angelo, modelled in 1753 by Peter Anton von Verschaffelt (1710–1793).

Michael's icon on the northern deacons' door on the iconostasis of Hajdúdorog. The archangel is often depicted on iconostases' doors as a defender of the sanctuary.

Archangel Michael by Emily Young in the grounds of St Pancras New Church. Plaque inscription: "In memory of the victims of the 7th July 2005 bombings and all victims of violence. 'I will lift up my eyes unto the hills' Psalm 121"

St. Michael the Archangel and the Dragon. Queen of Archangels Roman Catholic Parish, Clarence, PA

St Michael's Victory over the Devil, a sculpture by Jacob Epstein.

Churches named after Michael[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Structured gallery of churches dedicated to Archangel Michael. |

- Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel (es), San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato Mexico World Heritage Site

- Sacra di San Michele (Saint Michael's Abbey), near Turin, Italy

- Pfarrei Brixen St. Michael with the White Tower, Brixen, Italy

- Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, in Brussels, Belgium

- Mont-Saint-Michel, Normandy, France – a World Heritage Site

- St. Michael's Cathedral Basilica (Toronto), Canada

- St. Michael's Cathedral (Izhevsk), Russia

- St. Michael's Cathedral, Qingdao, China

- Chudov Monastery in the Moscow Kremlin

- Cathedral of the Archangel in the Moscow Kremlin – a World Heritage Site

- Sanctuary of Monte Sant'Angelo, Gargano, Italy – a World Heritage Site

- St Michael's Mount, Cornwall, UK

- St. Michael's Basilica, Miramichi, Canada

- Skellig Michael, off the Irish west coast – a World Heritage Site

- St Michael's Cathedral, Coventry, UK

- St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, Kyiv, Ukraine

- Basilica of St Michael the Archangel, Pensacola, Florida, United States

- St. Michael's Church, Vienna in Vienna, Austria

- Tayabas Basilica, Tayabas, Quezon, Philippines

- , Pontevedra, Negros Occidental, Philippines

- St. Michael's Church, Berlin, Germany

- St. Michael's Jesuit church, Munich, Germany

- St. Michael's Cathedral, Belgrade in Belgrade, Serbia

- Cathedral of St. Michael the Archangel in Gamu, Isabela, Philippines

- Mission San Miguel Arcángel, Sann Miguel, California, United States, one of the California Missions

- St Michael at the North Gate, Oxford, UK

- St. Michael’s Church, Mumbai, India

- Church of St. Michael, Štip, Republic of Macedonia

- [The Church Of St Michael and All Angels, Colombo 03, Sri Lanka

See also[]

- Angelus

- Biblical cosmology

- Christian angelic hierarchy

- Guardian Angel of Portugal

- Hierarchy of angels

- List of angels in theology

- Metatron

- Saint Michael, patron saint archive

- Saint Michael in the Catholic Church

- Seraph

- Theophory in the Bible

- Uriel

References[]

- ^ "Bible gateway, Daniel 12:1". Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- ^ Alban Butler, The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and other Principal Saints. 12 vols. B. Dornin, 1821; p. 117

- ^ "Benedict XVI joins Pope Francis in consecrating Vatican to St Michael Archangel". news.va. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ^ Finley, Mitch (2011). The Patron Saints Handbook. The Word Among Us Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-59325403-2. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ "St. Michael, the Archangel – Saints & Angels". Catholic.org. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ "Surah Al-Baqarah [2:98]".

- ^ "List of books attesting the title of "Saint Michael the Taxiarch"" (in English and German).

- ^ B. Osswald (PhD) (2008). From Lieux de Pouvoir to Lieux de Mémoire: The Monuments of the Medieval Castle of Ioannina through the Centuries. Edizioni Plus-Pisa University Press. ISBN 978-88-8492-558-9. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018.

- ^ Who's who in the Jewish Bible by David Mandel 2007 ISBN 0-8276-0863-2 p. 270

- ^ Daniel: Wisdom to the Wise: Commentary on the Book of Daniel by Zdravko Stefanovic 2007 ISBN 0-8163-2212-0 p. 391

- ^ Jump up to: a b Revelation 12–22 by John MacArthur 2000 ISBN 0-8024-0774-9 pp. 13–14

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Angels, by Rosemary Guiley, 2004 ISBN 0-8160-5023-6, p. 49

- ^ Wensinck, A.J. (1960–2009). The encyclopaedia of Islam. - Mīkāl (New ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- ^ Abdul-Rahman, Muhammad Saed (29 October 2009). Tafsir Ibn Kathir Juz' 26 (Part 26): Al-Ahqaf 1 to AZ-Zariyat 30 2nd Edition (abridged ed.). MSA Publication Limited. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-86179-748-3. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Midrash Pirke R. El. xxvi

- ^ "Jewish Encyclopedia – Michael". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ Midrash Deut. Rabbah xi. 6

- ^ Yer. Ber. ix. 13a

- ^ Baruch Apoc. Ethiopic, ix. 5

- ^ Midrash Abkir, in Yalḳ., Gen. 110

- ^ Midrash Exodus Rabbah xviii. 5

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Michael the Archangel". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Richard Freeman Johnson (2005), Saint Michael the Archangel in Medieval English Legend ISBN 1-84383-128-7; pp. 33–34

- ^ Monferrer-Sala, J. P. (2014). "One More Time on the Arabized Nominal Form Iblīs", Studia Orientalia Electronica, 112, 55-70. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/store/article/view/9526

- ^ Anna Jameson (2004), Sacred and Legendary Art ISBN 0-7661-8144-8; p. 92

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alban Butler, The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and other Principal Saints. 12 vols. Dublin: James Duffy, 1866; p. 320

- ^ Online, Catholic. "Holy Michael, the Archangel, Defend Us in Battle - Prayers". Catholic Online.

- ^ Cadwallader, Alan H.; Michael Trainor (2011). Colossae in Space and Time. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 323. ISBN 978-3-525-53397-0. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ Donna-Marie O'Boyle, Catholic Saints Prayer Book OSV Publishing, 2008 ISBN 1-59276-285-9 p. 60

- ^ Starr, Mirabai. Saint Michael: The Archangel, Sounds True, 2007 ISBN 1-59179-627-X p. 2

- ^ Starr, p. 39.

- ^ Butler 1821, p. 117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Michael McGrath, Patrons and Protectors. Liturgy Training, 2001. ISBN 1-56854-109-0.

- ^ "Prayer to St Michael". EWTN.

- ^ Matthew Bunson, The Catholic Almanac's Guide to the Church, OSV Publishing, 2001 ISBN 0-87973-914-2 p. 315

- ^ Amy Welborn, The Words We Pray. Loyola Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8294-1956-X, p. 101.

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X p. 123

- ^ EWTN "The Chaplet of St. Michael the Archangel"

- ^ James Joyce (17 April 2008). Ulysses. OUP Oxford. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-19-162349-3.

- ^ Baun, Jane (2007). Tales from Another Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 391 et passim. ISBN 978-0-521-82395-1. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ Eastern Orthodox Theology: A Contemporary Reader by Daniel B. Clendenin (2003) ISBN 0801026512, p. 75

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, by John Anthony McGuckin (2011) ISBN 1405185392 p. 30

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life, by Ernst Benz (2008) ISBN 0202362981, p. 16

- ^ A Geography of Russia and Its Neighbors, by Mikhail S. Blinnikov (2010) ISBN, p. 203

- ^ Architectures of Russian Identity, 1500 to the Present, by James Cracraft (2003) ISBN 0801488281, p. 42

- ^ Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity, by Otto Friedrich August Meinardus (2010) ISBN 977-424-757-4 pp. 27, 117, 147

- ^ Money, Land and Trade: An Economic History of the Muslim Mediterranean, by Nelly Hanna (2002) ISBN 1-86064-699-9, p. 226

- ^ Armentrout, Don S. (1 January 2000). An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church. Church Publishing, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 9780898697018.

- ^ The Methodist New Connexion Magazine and Evangelical Repository, Volume XXXV, Third Series. London: William Cooke. 1867. p. 493.

- ^ Graham, Billy (1995). Angels. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 9780849938719. p. PT31.

- ^ Graham (1995) p. PT32

- ^ "John A. Lees, "Michael" in James Orr (editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia(Eerdmans 1939)". Internationalstandardbible.com. 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ "The Angels of Michael; Revelation 12:7–12," by Robert W. Bertram, published in Cresset 21, No. 9 (September, 1958): 1214, p. 2

- ^ "Spirituality is for Angels – The Angels of Michael", by Robert W. Bertram, in Ecumenism, The Spirit and Worship, 126–169. Edited by Leonard J. Swindler. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1967, p. 4

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia; James Orr, M.A., D.D., General Editor; John L. Nuelsen, D.D., LL.D.; Edgar Y. Mullins, D.D., LL.D. Assistant Editors; Morris O. Evans, D.D., Ph.D., Managing Editor; Volume III. Heresy-Naarah; Chicago, The Howard-Severance Company, 1915., PDF p. 693; Internally p. 2048

- ^ The Imperial Bible-Dictionary, by the Rev. Patrick Fairbairn, D.D (1866), p. 234

- ^ The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible; Volume 4; M–P, Revised, Full-Color Edition; Merrill C. Tenney, General Editor/Moises Silva, Revision Editor. 2010 – https://books.google.com/books?id=S4MZREX03u0C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ A Comprehensive Dictionary of the Bible (1868), by Sir William Smith, pp. 645–646

- ^ Prophecy viewed in respect to its distinctive nature, its special function, and proper interpretation. by Patrick Fairbairn, D.D. (1865), PDF p. 344; Internally p. 325

- ^ The Revelation of St. John, expounded for those who search the Scriptures. by E. W. Hengstenberg (1851), pp. 474–475; Internally pp. 466–467, with notations – https://archive.org/stream/revelationstjoh01fairgoog#page/n474/mode/1up https://archive.org/stream/revelationstjoh01fairgoog#page/n475/mode/1up

- ^ A Commentary Of The Holy Scriptures: Critical, Doctrinal And Homiletical, With Special Reference To Ministers And Students, By John Peter Lange, D.D. (1874), p. 248 – https://books.google.com/books?id=g5tBAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ The Preacher's Complete Homiletical Commentary on the Old Testament (1892), pp. 227, 274 – https://archive.org/stream/homileticalcomme27robi#page/227/mode/1up https://archive.org/stream/homileticalcomme27robi#page/274/mode/1up

- ^ Andrew Willet, Sixfold Commentary (Hexapla in Danielem) (1610), p. 384 – http://rarebooks.dts.edu/viewbook.aspx?bookid=1422

- ^ William Baxter Godbey's Commentary on the New Testament; Revelation 12, p. 62 – http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/ges/view.cgi?bk=65&ch=12 http://www.enterhisrest.org/history/wg-rev.pdf

- ^ The London Encyclopedia, or Universal Dictionary, Volume. XIV. Medicine to Mithridates; Edited by Thomas Curtis, of Grove House School, Islington. 1839., p. 483 – https://books.google.com/books?id=5eQqJ-AGK-YC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ The Monthly Review for January, 1806. By Ralph Griffiths., p. 333 – https://books.google.com/books?id=Ff7kAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Sacred Dissertations, on what is commonly called the Apostles' Creed. By Herman Witsius, D.D. Professor of Divinity in the Universities of Franeker, Utrecht, and Leyden. Translated from the Latin, and followed with Notes, Critical and Explanatory, by Donald Fraser, Minister of the Gospel, Kennoway. In Two Volumes. Volume II. 1823., p. 538 – https://books.google.com/books?id=DKQPAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Who is “The (Arch)angel of the Lord”?; Posted September 6, 2014 by Website Admin, by Francis Nigel Lee, p. 3, Web p. 2 – http://www.dr-fnlee.org/who-is-the-archangel-of-the-lord/2/

- ^ The Days of Vengeance, An Exposition of the Book of Revelation, by David Chilton, copyright 1987., p. 312 Notes, No. 27 – https://archive.org/stream/DaysOfVengeance-DavidChilton/Days of Vengeance David Chilton#page/n337/mode/1up

- ^ The Bible Doctrine of God, Jesus Christ, The Holy Spirit, Atonement, Faith, And Election; to which is prefixed some Thoughts of Natural Theology and the Truth of Revelation; by William Kinkade, pp. 152–154 – http://www.archive.org/stream/bibledoctrineofg00kink#page/152/mode/1up http://www.archive.org/stream/bibledoctrineofg00kink#page/153/mode/1up http://www.archive.org/stream/bibledoctrineofg00kink#page/154/mode/1up

- ^ "Ezekiel, Daniel" edited by Carl L. Beckwith, p. 405 – https://books.google.com/books?id=gSMDd60ohdkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ A Cyclopaedia of Biblical literature; Volume III, by John Kitto, D.D., F.S.A. Third Edition (1876), p. 158 – https://books.google.com/books?id=7DAHAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Baptist Confession of Faith (1689) – With slight revisions by C. H. Spurgeon Archived 2010-04-07 at the Wayback Machine – spurgeon.org – Phillip R. Johnson – 2001 – Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Morning and Evening – Charles Haddon Spurgeon – Devotionals by Spurgeon Sermons – Spurgeon Sermons with C.H. Spurgeon – Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Charles Spurgeon; Morning and Evening Daily Readings; Complete and Unabridged Classic KJV Edition; Morning Devotion; October 3 on Hebrews 1:14; 1991., p. 554 – https://books.google.com/books?id=w0pqbDq4F-AC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Charles Spurgeon; Morning by Morning; or, Daily Readings for the Family or the Closet; New York and Sheldon Company 498 and 500 Broadway. 1866, p. 227 – https://books.google.com/books?id=0SAeAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false http://www.heartlight.org/spurgeon/1003-am.html

- ^ The Angelic Life, Charles Haddon Spurgeon, Sermon No. 842.

- ^ Clayton, Robert (February 13, 1751). "An essay on spirit". London, printed: [etc.] – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography: Clayton, Robert

- ^ John Walsh, Colin Haydon & Stephen Taylor, eds. (1993) The Church of England c. 1689 – c. 1833: from Toleration to Tractarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-41732-5; p. 47

- ^ Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, D.C., 1957. Chapter 8 "Christ, and Michael the Archangel".

- ^ Seventh Day Adventists: What do they believe? by Val Waldeck Pilgrim Publications (April 5, 2005) p. 16

- ^ "The Remnant". Adventist World. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ Bible readings for the home by 7th Day Adventists. London. 1949. p. 266.

- ^ Reasoning from the Scriptures, 1985, Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, p. 218

- ^ Insight on the Scriptures. 2. Watch Tower Society. pp. 393–394. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ^ What Does the Bible Really Teach?. Watch Tower Society. pp. 218–219. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ^ "Angels—How They Affect Mankind". The Watchtower. Watch Tower Society: 21–25. March 15, 2007. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ^ What Does The Bible Really Teach?. Watch Tower Society. p. 87.

- ^ "Your Leader Is One, the Christ". The Watchtower: 21. September 15, 2010.

- ^ Millet, Robert L. (February 1998), "The Man Adam", Liahona

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 27:11

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 107:53–56

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 128:21

- ^ "King, Daniel "A Christian Qur'an? A Study in the Syriac Background of the Qur'an as Presented in the Work of Christoph Luxenberg," JLARC 3, 44–71 (2009)" (PDF). School of History, Archaeology and Religion. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mikal - Angel, Meaning, & Islam". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ Abdul-Rahman, Muhammad Saed (7 January 2013). Tafsir Ibn Kathir Juz' 1 (Part 1): Al-Fatihah 1 to Al-Baqarah 141 2nd Edition. MSA Publication Limited. p. cccxli. ISBN 978-1-86179-826-8. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ John L. Esposito Oxford Dictionary of Islam Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-195-12559-7 p. 200

- ^ MacDonald, John (1964). "The Creation of Man and Angels in the Eschatological Literature: [Translated Excerpts from an Unpublished Collection of Traditions]". Islamic Studies. 3 (3): 285–308. JSTOR 20832755.

- ^ At-Tabrizi, Khatib. Mishkat al-Masabih 2215 - The Excellent Qualities of the Qur'an - كتاب فضائل القرآن, Hadith 2215 - Sunnah.com. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Sahih Muslim, Book of Virtues (#43), Hadith 63 (reference: Sahih Muslim 2306a)

- ^ "Aamal e Umme Dawood".

- ^ "Dua of Umm Dawood" (PDF). www.wilayatmission.org. Retrieved 2021-02-13.

- ^ The Birth of the Prophet Muḥammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam – p. 21, Marion Holmes Katz – 2007

- ^ The Logic of The Revelation of St. John|Stephen Beebe|Baha'i Publishing Trust|2001|pgs. 103-104

- ^ Daniel 10:7-13

- ^ The Apocalypse Unsealed|Robert F. Riggs|Philosophical Library, Inc.|1982|pgs. 160,164

- ^ Steiner, Rudolf (1994) [1917]. Christopher Bamford (ed.). The Archangel Michael. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press. ISBN 0-88010-378-7.

- ^ Betz, Hans (1996). The Greek Magical Papyri In Translation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226044477. Entries: "Introduction to the Greek Magical Papyri" and "PGM III. 1–164".

- ^ Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius (2000) [1531]. Donald Tyson (ed.). Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Llewellyn Publications. pp. 274, 285, 289, 469. ISBN 0-87542-832-0.

- ^ "Peter of Abano: Heptameron, or Magical Elements". esotericarchives.com.

- ^ "Ch. xviii: Considerations of the Lord's Day". esotericarchives.com.

- ^ "Ch. xxi: Considerations of Wednesday". esotericarchives.com.

- ^ Saint Michael the Archangel in Medieval English Legend by Richard Freeman Johnson 2005 ISBN 1-84383-128-7 p. 105

- ^ Icons and saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church by Alfredo Tradigo 2006 ISBN 0-89236-845-4 p. 46

- ^ The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity 2010 by Ken Parry ISBN 1-4443-3361-5 p. 242

- ^ "BBC - Cornwall Uncovered - Story The Legend of St Piran". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ The English Missal for the laity; 3rd ed. London: W. Knott, 1958; pp. 625–627

- ^ Cross & Livingstone (eds.) ODCC; p. 613

- ^ Ball, p. 586.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Knights of the Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe 1325–1520 by D'Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton 2000 ISBN 0-85115-795-5 pp. 427–428

- ^ Noted by Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919, 1924:56.

- ^ Angels in the early modern world By Alexandra Walsham, Cambridge University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-521-84332-4 p. 2008

- ^ Patron Saints by Michael Freze 1992 ISBN 0-87973-464-7 p. 170

- ^ Dronda, Javier (2013). Con Cristo o contra Cristo: Religión y movilización antirrepublicana en Navarra (1931–1936). Tafalla: Txalaparta. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-84-15313-31-1.

- ^ Netherlandish sculpture 1450–1550 by Paul Williamson 2002 ISBN 0-8109-6602-6 p. 42

- ^ Eastern Orthodoxy through Western eyes by Donald Fairbairn 2002 ISBN 0-664-22497-0 p. 148

- ^ "History of Dumfries". loreburne.co.uk. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ All Saints Sisters of the Poor: An Anglican Sisterhood in the Nineteenth Century (Church of England Record Society) by Susan Mumm 200 ISBN 0-85115-728-9 p. 48

- ^ "甘肃快3_官方彩购买". www.orderofstmichaelanglican.com.

- ^ Chaplain's Corner: Saint Michael, patron saint of the airborne, military. Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson Alaska.

- ^ http://foreignlegion.info/history/2rep/

- ^ Amélineau, "Contes et Romans de l'Egypte Chrétienne", ii. 142 et seq

- ^ Midrash Genesis Rabbah xliv. 16

- ^ Midrash Esther Rabbah iii. 8

- ^ Targum to Esther, vi. 1

- ^ comp. Josephus, "Ant." xiii. 10, § 3

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ginzberg, Louis, The Legends of the Jews, Vol. I: The Angels and The Creation of Man Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, (Translated by Henrietta Szold), Johns Hopkins University Press: 1998, ISBN 0-8018-5890-9

- ^ Makarios of Simonos Petra, The Synaxarion: the Lives of the Saints of the Orthodox Church, trans. Christopher Hookway (Holy Convent of the Annunciation of Our Lady 1998 ISBN 960-85603-7-3), p. 47.

- ^ Synaxarion, p. 47.

- ^ Synaxarion, p. 48.

- ^ Peers, Glenn (2001). Subtle bodies: representing angels in Byzantium. University of California Press. p. 144. ISBN 0-520-22405-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Saint Michael the Archangel in medieval English legend by Richard Freeman Johnson 2005 ISBN 1-84383-128-7 p. 68

- ^ Popular Romances of the West of England by Robert Hunt 2009 ISBN 0-559-12999-8 p. 238

- ^ Myths and Legends of Britain and Ireland by Richard Jones 2006 ISBN 1-84537-594-7 p. 17

- ^ The Medieval state: essays presented to James Campbell by John Robert Maddicott, David Michael Palliser, James Campbell 2003 ISBN 1-85285-195-3 pp. 10–11

- ^ Mont-Saint-Michel: a monk talks about his abbey by Jean-Pierre Mouton, Olivier Mignon 1998 ISBN 2-7082-3351-3 pp. 55–56

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Mont-St-Michel". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1 by Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin Gitlitz 2002 ISBN 1-57607-004-2 p. 398

- ^ Ball, p. 123.

- ^ EWTN The Chaplet of Saint Michael the Archangel

- ^ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 0-87973-454-X p. 267

- ^ John Milton, Paradise Lost 1674 Book VI line 320

- ^ Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth (1851). The Golden Legend. Boston: Ticknor, Reed and Fields.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Saint Michael the Archangel in medieval English legend by Richard Freeman Johnson 2005 ISBN 1-84383-128-7 pp. 141–147

- ^ Icons and saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church by Alfredo Tradigo 2006 ISBN 0-89236-845-4 p. 188

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X p. 520

- ^ Constantine and the Christian empire by Charles Matson Odahl 2004 ISBN 0-415-17485-6 p. 315

- ^ "Vatican website: Sistine Chapel". Vaticanstate.va. Archived from the original on 2010-05-26. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- ^ Saints in art by Rosa Giorgi, Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 0-89236-717-2 pp. 274–276

Sources[]

- Ball, Ann. 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X

- Butler, Alban. The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and other Principal Saints. 12 vols. B. Dornin, 1821

- Starr, Mirabai. Saint Michael: The Archangel, Sounds True, 2007 ISBN 1-59179-627-X

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archangel Michael. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Michael (archangel) |

- Michael (archangel)

- Angels in the Book of Enoch

- Archangels in Christianity

- Archangels in Islam

- Archangel in Judaism

- Christian saints from the New Testament

- Christian saints from the Old Testament

- Individual angels

- Patron saints of France

- Quranic figures

- Angels of death

- Adam and Eve in Mormonism