Mihrimah Sultan (daughter of Suleiman I)

| Mihrimah Sultan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

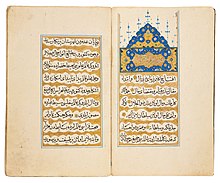

Portrait by Cristofano dell'Altissimo titled Cameria Solimani, 16th century | |||||

| Born | c. 1522 Old Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire (present day Istanbul, Turkey) | ||||

| Died | 25 January 1578 (aged 55–56) Old Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire (present day Istanbul, Turkey) | ||||

| Burial | Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Ayşe Sultan | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Suleiman the Magnificent | ||||

| Mother | Hurrem Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Mihrimah Sultan (Ottoman Turkish: مهر ماه سلطان, Turkish pronunciation: [mihɾiˈmah suɫˈtan]; c. 1522 – 25 January 1578) was an Ottoman princess, the daughter of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife, Hurrem Sultan. She was the most powerful imperial princess in Ottoman history and one of the prominent figures during the Sultanate of Women.

Names[]

Mihrimah or Mihrümah[1][2] means "Sun and Moon",[3][4] or "Moon of the Suns"[5] in Persian.[4] To Westerners, she was known as Cameria,[6] which is a variant of "Qamariah", an Arabic version of her name meaning "of the moon". Her portrait by Cristofano dell'Altissimo entitled as Cameria Solimani.[7] She was also known as Hanım Sultan, which means "Madam Princess".[8]

Early life[]

Mihrimah was born in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1522[9][10][11] during the reign of her father, Suleiman the Magnificent. Her mother was Hurrem Sultan,[9][10][11] an Orthodox priest's daughter,[12] who was the current Sultan's concubine at the time. In 1533 or 1534, her mother, Hurrem, was freed and became Suleiman's legal wife.[13] She had five brothers, Şehzade Mehmed, Şehzade Abdullah, who died at the age of three years, Şehzade Selim (future Selim II), Şehzade Bayezid, and Şehzade Cihangir.[9][10] She was well-educated and disciplined. She was also sophisticated, eloquent and wellread.[4]

Marriage[]

In 1539, Suleiman decided that Mihrimah be married to Rüstem,[14] a devshirme from Croatia who rose to become Governor of Diyarbakır and later, Suleiman's Grand Vizier.[15] However, Hurrem believed that she should be married to more handsome governor of Cairo.[14] According to a rumor circulated by Rüstem's enemies, he had leprosy. The doctor dispatched to Diyarbakır to examine him found proof that he was not leprous. There was a flea in his clothing, despite the fact that the fastidious Rüstem changed his garments daily.[16]

The marriage took place on 26 November 1539[17][18][19][20] in the Old Palace,[21] when Mihrimah was seventeen.[22] Her wedding ceremony and the celebration for her younger brothers Bayezid and Cihangir's circumcision occurred on the same day,[23][20][24] the collective festivities lasting fifteen days.[25] Five years later in 1544, her husband was selected by Suleiman to become Grand Vizier.[26] He held the post until his death in 1561, except for a two-year interval when he was dismissed to assuage popular outrage following the execution of the Şehzade Mustafa in 1553.[27][28]

Shortly after her wedding she developed a rheumatoid-like condition and spent most of her life dealing with the illness.[4] In 1544 she traveled to Bursa together with her mother and husband and a large military escort.[29] Although Mihrimah and her mother made efforts to promote Rüstem as an intimate of the sultan, He was, however, kept at a distance from the royal presence.[16] Mihrimah and Rüstem had one daughter,[30] Ayşe Sultan,[31] born on 25 August 1547.[30]

In 1554, Mihrimah suffered a life-threatening miscarriage from which she managed to recover. The couple lived in Pera, as recorded by an anonymous hand, though it is far more likely that they settled in Mihrimah's palace in Üsküdar.[32] In March 1558, Shaykh Qutb al-Din al-Nahrawali, a Meccan religious figure visited Istanbul.[33] In April, he met Mihrimah, and presented her gifts,[34] which were taken apart from her mother's gifts on the suggestion of Shaykh Badr-al Din al-Qaysuni, the sultan's head physician.[35] He met her again in June just before he left Istanbul for Cairo.[36]

After Rüstem's death in 1561,[37] she offered Semiz Ali Pasha, who had succeeded Rüstem as the grand vizier, to marry her. However, the pasha declined the offer. She then chose not to marry again,[38] returning instead to the royal palace.[39]

Political affairs[]

Although there is no proof of Hurrem or Mihrimah's direct involvement in her half-brother Şehzade Mustafa's downfall, Ottoman sources and foreign accounts indicate that it was widely believed that Hurrem, Rüstem and Mihrimah worked first to eliminate Mustafa so as ensure the throne to Hurrem's son and Mihrimah's full-brother, Bayezid.[40][41][42] The rivalry ended in a loss for Mustafa when he was executed by his own father's command in 1553 during the campaign against Safavid Persia because of fear of rebellion. Although this stories were not based on first-hand sources,[43] this fear of Mustafa was not unreasonable. Had Mustafa ascended to the throne, all Mihrimah's full-brothers (Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir) would have likely been executed, according to the fratricide custom of the Ottoman dynasty, which required all brothers of the new sultan be executed to avoid feuds among imperial siblings.[26][40] The three of them were also blamed for the execution in 1555 of the Grand Vizier Kara Ahmed Pasha, whose elimination cleared the way for Rüstem's return as the Grand Vizier.[44]

Her mother sent letters to Sigismund II, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and the contents of her letters were mirrored in letters written by Mihrimah, and sent by the same courier, who also carried letters from the sultan and her husband Rüstem Pasha the Grand Vizier.[45] Mihrimah also became Suleiman's advisor, his confidant and his closest relative.[46] After Hurrem's death, Mihrimah took her mother's place as her father's counselor,[20] urging him to undertake the conquest of Malta in 1565,[47] and sending him news and forwarding letters for him when he was absent from capital.[46] She enlisted the help of the Grand Vizier Semiz Ali Pasha, and promising to outfit four hundred ships at her own expense. However, Suleiman and his son Selim prevented the campaign from going forward so thar the admiral, Piyale Pasha, might remain in Istanbul with his new wife, Gevherhan Sultan, Selim's daughter.[48] She also most likely fuelled Suleiman's decision to launch a campaign against Hungary in 1566, where he met his death in Szigetvár.[47]

Due mainly to temporary closures of the western and/or eastern grain markets, shortages and poor harvests, the sixteenth century saw several crises. The Ragusans managed to bridge them thanks to the supplies of Ottoman grain, in which Mihrimah played an essential role.[49] The reason underlying such Ragusan approach to Mihrimah may be sought in the tensions between the Republic and the Ottomans, notably with kapudan pasha, Piyale Pasha. Namely, during the Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565, several Ragusan ships sailed in the Christian fleet. Piyale Pasha reported on this to the Porte. To Ragusan horror, his ships sailed into Ragusan waters and raided the island of Mljet. However, true problems emerged in the spring and summer of 1566, that is, after Ragusan ambassadors had petitioned with Mihrimah to act as their protector.[47]

In later years Mihrimah retired to the Old Palace.[50] When Selim ascended the throne in 1566, he made his way to the harem at the earliest opportunity after arriving in the capital, and sought Mihrimah, as their mother had died eight years earlier.[51] She continued to act as advisor to Selim.[4] Her influence, due mainly to financial power, did not decline. As soon as he came to power, Selim turned to her for help as he needed money, after which she lend him fifty thousand gold coins.[38] In 1571, the Ragusans asked her to speak with the sultan when the time allowed her, and to recommend them and "spare a couple of kind words for their love's sake".[52]

In 1575, during the reign of her nephew Sultan Murad III, her daily stipend consisted of 600 aspers.[53] The French refused to return two Turkish women who had been captured at sea by Henry III's brother-in-law and made members of Catherine de' Medici's court. Interceding on behalf of the Turkish women were Mihrimah and her niece, Ismihan Sultan.[54] Cığalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha, married her granddaughter in October 1576. Mihrimah, possessor of enormous heritage, not only provided Sinan with a huge dowry including gold and valuable clothes, but also showed her support for him against his rivals inside the court such as Safiye Sultan, Ferhad Pasha, Damat Ibrahim or Halil Pashas who would be glad to see him disfavored.[55]

Charities[]

Mihrimah also sponsored a number of major architectural projects. Her most famous foundations are the two Istanbul-area mosque complexes that bear her name, both designed by her father's chief architect, Mimar Sinan. Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (Turkish: Mihrimah Sultan Camii), also known as İskele Mosque (Turkish: Iskele Camii), which is one of Üsküdar's most prominent landmarks and was built between 1543 or 1544[56] and 1548.[57] The second mosque is also named as Mihrimah Sultan Mosque at the Edirne Gate, at the western wall of the old city of Istanbul. Its building took place from 1562 to 1565.[58]

The twin minaret mosque complex in Üsküdar, a prominent landmark, consisted of a mosque, a madrasah, a soup kitchen to feed the poor, a clinic and a primary school. With the exception of the mosque, the primary school, library and madrasah are currently used to serve as an outpatient clinic. The mosque in Edirnekapı consists of a fountain, madrasah and hammam. Unlike its namesake, it features a single minaret.[4][37][59]

She also commissioned the repair of 'Ayn Zubaydah, the spring in Mecca, and the established a foundation to supply wrought iron to the navy.[4]

Mimar Sinan[]

Mimar Sinan, a sixteenth century architect was allegedly in love with Mihrimah.[4] According to a story, he had first seen her while she was accompanying her father during the sultan's Moldova Campaign.[4] To impress her, Sinan built a bridge spanning the Prut River in just thirteen days. He asked for her hand in marriage only to have his proposal rejected by her father. He in turn poured his heart into his architecture. He built the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Üsküdar to resemble the silhouette of a woman with her skirt sweeping the ground.[4]

Death[]

Mihrimah died in Istanbul on 25 January 1578[60][61][62] outliving all of her siblings. She is the only one of Suleiman's children[63] to be buried in his tomb, the Süleymaniye Mosque complex.[4][64][37][62]

In popular culture[]

- In the 2011–2014 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, she is portrayed by Pelin Karahan.[65]

- In The Architect's Apprentice, a 2014 novel by Elif Shafak, she is a central character.[66][67]

References[]

- ^ Necdet Sakaoğlu (2007). Famous Ottoman Women. Avea. p. 105. ISBN 978-975-7104-77-3.

- ^ Fen Fakültesi İstanbul Üniversitesi (1967). Lectures Delivered on the 511th Anniversary of the Conquest of İstanbul. Fen Fakültesi Döner Sermaye Basımevi. p. 13.

- ^ Isom-Verhaaren 2016, p. 158.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k "Notable life of Mihrimah Sultan". DailySabah. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Arthur Stratton (1971). Sinan: The Biography of One of the World's Greatest Architects and a Portrait of the Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire. Scribner. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-684-12582-4.

- ^ Giorgio Vasari; Francesco Priscianese; Pietro Aretino; Sperone Speroni; Lodovico Dolce (23 April 2019). Lives of Titian. Getty Publications. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-60606-587-7.

- ^ David Geoffrey Alexander (2003). From the Medicis to the Savoias: Ottoman Splendour in Florentine Collections. Sabanci University, Sakip Sabanci Müzesi. p. 94. ISBN 978-975-8362-37-0.

- ^ Nahrawālī & Blackburn 2005, p. 201 and n. 547.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Peirce 1993, p. 60.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yermolenko 2005, p. 233.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Uluçay 1992, p. 65.

- ^ Yermolenko 2005, p. 234.

- ^ Yermolenko 2005, p. 235.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Isom-Verhaaren 2016, p. 154.

- ^ Vovchenko, Denis (18 July 2016). Containing Balkan Nationalism: Imperial Russia and Ottoman Christians, 1856-1914. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-061291-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peirce 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Tolga Uslubaş; Yılmaz Keskin (2007). Alfabetik Osmanlı tarihi ansiklopedisi. Karma Kitaplar. p. 393. ISBN 978-9944-321-50-1.

- ^ Pars Tuğlacı (1985). Türkiyeʼde kadın. Cem Yayınevi. p. 316.

- ^ Metin And (2009). 16. yüzyılda İstanbul: kent, saray, günlük yaşam. Yapı Kredi Yayınları. p. 145. ISBN 978-975-08-1832-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Uluçay 1992, p. 66.

- ^ Dünden bugüne İstanbul ansiklopedisi. Kültür Bakanlığı. 1994. p. 453. ISBN 978-975-7306-05-4.

- ^ Miović 2018, p. 98.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 68, 76, 123.

- ^ Miović 2018, p. 97.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 68.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Isom-Verhaaren 2016, p. 155.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 72.

- ^ Nahrawālī & Blackburn 2005, p. 82 n. 208.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 61.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Atçıl 2020, p. 14.

- ^ Hans Georg Majer; Sabine Prätor; Christoph K. Neumann (2002). Arts, women and, scholars. Simurg. p. 105. ISBN 978-975-7172-64-2.

Ayşe Sultan duhter-i hazret-i Mihrümāh Sulțān el-mezbūre zevce-i Ahmed Paşa

- ^ Miović 2018, p. 100-101.

- ^ Nahrawālī & Blackburn 2005, p. 158.

- ^ Nahrawālī & Blackburn 2005, p. 176.

- ^ Nahrawālī & Blackburn 2005, p. 162-63.

- ^ Nahrawālī & Blackburn 2005, p. 207.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Uluçay 1992, p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Atçıl 2020, p. 21.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peirce 1993, p. 79.

- ^ Isom-Verhaaren 2016, p. 156.

- ^ Uluçay 1992, p. 66-67.

- ^ Yermolenko 2005, p. 236.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 84.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 221.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peirce 1993, p. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Miović 2018, p. 106.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 68-69.

- ^ Miović 2018, p. 102.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 261.

- ^ Miović 2018, p. 107.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 127-28.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 227.

- ^ Biçer, Merve (2014). Cigalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha: A 16th Century Ottoman Comvert in the Mediterranean World (Master Thesis). Department of History İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University, Ankara. p. 48.

- ^ Isom-Verhaaren 2016, p. 157.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 201.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 23, 201.

- ^ "MİHRİMAH SULTAN KÜLLİYESİ Üsküdar'da İskele Meydanı'nın kuzeyinde Paşalimanı caddesi başında inşa edilmiş XVI. yüzyıla ait külliye". İslam Ansiklopedisi. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı (1988). İslâm ansiklopedisi: Mısra - Muhammediyye. Türkiye Diyanet Vakf ıİslâm Ansiklopedisi Genel Müdürlüğü. p. 40. ISBN 978-975-389-402-9.

- ^ Osman Gazi'den Sultan Vahidüddin Han'a Osmanlı tarihi. Çamlıca Basım Yayın. 2014. p. 120. ISBN 978-9944-905-39-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miović 2018, p. 108.

- ^ Isom-Verhaaren 2016, p. 164.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 190.

- ^ "Muhteşem Yüzyıl'ın Mihrimah Sultan'ı Pelin Karahan 10 dakikada boşandı - Son Dakika Magazin Haberleri | STAR". Star.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Atamian, Christopher (8 June 2015). "'The Architect's Apprentice,' by Elif Shafak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "The Architect's Apprentice by Elif Shafak, book review: The domes of". The Independent. 30 October 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

Bibliography[]

- Leslie Peirce (1993). Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508677-5.

- Yermolenko, Galina (April 2005). "Roxolana: "The Greatest Empresse of the East". DeSales University, Center Valley, Pennsylvania. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Isom-Verhaaren, Christine (11 April 2016). "Mihrimah Sultan: A Princess Constructs Ottoman Dynastic Identity". In Christine Isom-Verhaaren; Kent F. Schull (eds.). Living in the Ottoman Realm: Empire and Identity, 13th to 20th Centuries. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253019486.

- Uluçay, Mustafa Çağatay (1992). Padışahların kadınları ve kızları. Türk Tarihi Kurumu Yayınları.

- Miović, Vesna (2 May 2018). "Per favore della Soltana: moćne osmanske žene i dubrovački diplomati". Anali Zavoda za povijesne znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti u Dubrovniku (in Croatian) (56/1): 147–197. doi:10.21857/mwo1vczp2y. ISSN 1330-0598.

- Atçıl, Zahit (2020). "Osmanlı Hanedanının Evlilik Politikaları ve Mihrimah Sultan'ın Evliliği". Güneydoğu Avrupa Araştırmaları Dergis (34): 1–26.

- Nahrawālī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad; Blackburn, Richard (2005). Journey to the Sublime Porte: the Arabic memoir of a Sharifian agent's diplomatic mission to the Ottoman Imperial Court in the era of Suleyman the Magnificent; the relevant text from Quṭb al-Dīn al-Nahrawālī's al-Fawāʼid al-sanīyah fī al-riḥlah al-Madanīyah wa al-Rūmīyah. Orient-Institut. ISBN 978-3-899-13441-4.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mihrimah Sultan. |

- 1520s births

- 1578 deaths

- People of the Ottoman Empire of Ukrainian descent

- Daughters of Ottoman sultans

- 16th-century Ottoman royalty

- 16th-century women of the Ottoman Empire