Mission San Fernando Rey de España

Mission San Fernando Rey de España, c. 1885 | |

Location in the San Fernando Valley | |

| Location | 15151 San Fernando Mission Blvd. Los Angeles, California 91345 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°16′23″N 118°27′40″W / 34.2731°N 118.4612°WCoordinates: 34°16′23″N 118°27′40″W / 34.2731°N 118.4612°W |

| Name as founded | La Misión del Señor Fernando, Rey de España[1] |

| English translation | The Mission of Saint Ferdinand, King of Spain |

| Patron | Ferdinand III of Castile[2] |

| Nickname(s) | "Mission of the Valley"[3] |

| Founding date | September 8, 1797[4] |

| Founding priest(s) | Father Fermín Lasuén[5] |

| Founding Order | Seventeenth[2] |

| Military district | Second[6] |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) | Tataviam, Tongva Fernandeño, Gabrieleño |

| Native place name(s) | 'Achooykomenga, Pasheeknga[7] |

| Baptisms | 2,784[8] |

| Marriages | 827[8] |

| Burials | 1,983[8] |

| Secularized | 1834 (Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando)[2] |

| Returned to the Church | 1861[2] |

| Governing body | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles |

| Current use | Chapel-of-ease/Museum |

| Designated | 1971 |

| Delisted | 1974 |

| Reference no. | 71001076 |

| Designated | October 27, 1988 |

| Reference no. | 88002147 |

| Reference no. | #157 |

| Reference no. | 23[9] |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Mission San Fernando Rey de España is a Spanish mission in the Mission Hills community of Los Angeles, California. The mission was founded on September 8, 1797, and was the seventeenth of the twenty-one Spanish missions established in Alta California. Named for Saint Ferdinand, the mission is the namesake of the nearby city of San Fernando and the San Fernando Valley.

The mission was secularized in 1834 and returned to the Catholic Church in 1861; it became a working church in 1920. Today the mission grounds function as a museum; the church is a chapel of ease of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

History[]

In 1769, the Spanish Portolà expedition – the first Europeans to see inland areas of California – traveled north through the San Fernando Valley. On August 7 they camped at a watering place near where the mission would later be established. Fray Juan Crespí, a Franciscan missionary travelling with the expedition, noted in his diary that the camp was "at the foot of the mountains".[10]

Founding[]

The Rancho of Francisco Reyes (then the Alcalde of the Pueblo de Los Ángeles) was approved by the padres as a suitable site for the Mission. After brief negotiations with the Alcalde, the land was acquired (Mission records list Reyes as godfather to the first infant baptized at San Fernando).[11]

The mission was founded on September 8, 1797 by Father Fermín Lasuén who, with the assistance of and in the presence of troops and natives, performed the ceremonies and dedicated the mission to San Fernando Rey de España, making it the fourth mission site he had established; ten children were baptized on the first day. Fray Francisco Dumetz and his associate Fray Francisco Javier Uría labored in the mission until after 1800.[12]

Early in October 1797, 13 adults were baptized and the first marriage took place on October 8. At the end of the year, there were 55 neophytes. By 1800, there were 310 neophytes, 352 baptisms, and 70 deaths.[12]

1800s[]

Fray Dumetz left the mission in April 1802, then returned in 1804 and finally left the following year at the same time as Fray Francisco Javier Uría, who left the country. In 1805, Fray Nicolás Lázaro and Fray José María Zalvidea arrived at the mission; the latter was transferred to San Gabriel in 1806 and the former died at San Diego in August 1807. An adobe church with a tile roof was blessed in December 1806. Padres José Antonio Uría and Pedro Muños arrived in 1807; the former retired in November 1808 and was succeeded by Fray Martín de Landaeta while Fray José Antonio Urresti arrived in 1809 and became the associate of Fray Muñoz. Fray Landaeta died in 1816.[12]

During the first decade of the century, the neophyte population increased from 310 to 955, there had been 797 deaths, and 1468 baptisms. The largest number of baptisms in any one year was 361 in 1803.[13]

In 1804 there was a land controversy where the padres successfully protested against the granting of the Rancho Camulos to Francisco Ávila.[14]

1810s[]

Fray Urresti died in 1812 and was succeeded by Fray Joaquín Pascual Nuez in 1812 to 1814, Fray Vincente Pascual Oliva was stationed in the mission from 1814 to 1815. Fray Pedro Muñoz left California in 1817, and his place was taken by Fray Marcos Antonio de Vitoria from 1818 to 1820. Fray Ramón Ulibarri arrived in January and Fray Francisco González de Ibarra in October 1820. On December 21, 1812, an earthquake hit the area which caused enough damage to necessitate the introduction of 20 new beams to support the church wall. Before 1818, a new chapel was completed. During the period of 1810 to 1820 the population increased slightly, reaching its highest figure, 1,080, in 1819, after which its decline began.[14]

1820s[]

After Fray Ulibarri died in 1821, Fray Francisco González de Ibarra was stationed alone in the mission.[15]

Beginning of the Mexican era[]

After the Mexican Empire gained independence from Spain on September 27, 1821, the Province of Alta California became the Mexican Territory of Alta California. The missions continued under the rule of Mexico.

Fray Ibarra began to complain that the soldiers of his guard were causing problems by selling liquor and lending horses to the natives and in 1825, he declared that "the presidio was a curse rather than a help to the mission, that the soldiers should go to work and raise grain, and not live on the toil of the Indians, whom they robbed and deceived with talk of liberty while in reality they treated them as slaves." This led to a sharp reply from Captain Guerra, who advised the Padre to modify his tone. The amount of supplies furnished by the mission to the presidio from 1822 to April 1827 amounted to $21,203.[15]

1830s[]

Fray Ibarra continued his labors alone until the middle of 1835 when he retired to Mexico. His successor was Fray Pedro Cabot from San Antonio who was stationed until his death in October 1836.[16] After Fray Cabot's death, there is no mention of a missionary at San Fernando until August 1838 when Fray Blas Ordaz remained there during the rest of the decade. Down to 1834, the neophyte population decreased by less than 100 and the mission remained productive.[17]

Secularization[]

In October 1834, Comisionado Antonio del Valle took charge of the mission estates by inventory from Fray Ibarra. From then, the mission was to be a parish of the second class with a $1000 salary.[17]

Later history[]

In 1842, six years before the California Gold Rush, a brother of the mission mayordomo (foreman) made the first Alta California gold discovery in the foothills near the mission. In memory of that discovery, the place was given the name Placerita Canyon, but only small quantities of gold were found.[5][18]

In 1845, Governor Pío Pico declared the Mission buildings for sale under the Mexican secularization act of 1833 and, in 1846, made Mission San Fernando Rey de España de velicata his headquarters as Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando. The Mission was utilized in a number of ways during the late 19th century: north of the mission was the site of Lopez Station for the Butterfield Stage Lines; it served as a warehouse for the Porter Land and Water Company; and in 1896, the quadrangle was used as a hog farm.[19] In 1861, the Mission buildings and 75 acres of land were returned to the church after Charles Fletcher Lummis acted for preservation. The buildings were disintegrating as beams, tiles and nails were taken from the church by settlers.[20] San Fernando's church became a working church again in 1923 when the Oblate priests arrived. Many attempts were made to restore the old Mission from the early 20th century, but it was not until the Hearst Foundation gave a large gift of money in the 1940s, that the Mission was finally restored. The museum became the repository for heirlooms of the Mexican church evacuated during the Cristero revolt, and also holds part of the Doheny library.[21] The church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, but was extensively damaged by the 1971 San Fernando earthquake, and was completely rebuilt. Repairs were completed in 1974. It continues to be very well cared for and is still used as a chapel-of-ease. The Convento Building was separately listed on the Register in 1988. In 2003, comedian Bob Hope, a late-life convert to Catholicism, was interred in the Bob Hope Memorial Gardens; followed by his widow Dolores Hope in 2011.

Mission industries[]

The goals of the missions were, first, to spread the message of Christianity and, second, to establish a Spanish colony. Because of the difficulty of delivering supplies by sea, the missions had to become self-sufficient in relatively short order. Toward that end, neophytes were taught European-style farming, animal husbandry, mechanical arts and domestic crafts like tallow candle making.

Mission bells[]

Bells were vitally important to daily life at any mission. The bells were rung at mealtimes, to call the Mission residents to work and to religious services, during births and funerals, to signal the approach of a ship or returning missionary, and at other times; novices were instructed in the intricate rituals associated with the ringing the mission bell. The residents as referred to above were called neophytes (Indigenous persons) after baptism. There were five bells at the mission from 1769 to 1931.

A hundred-pound bell was unearthed in an orange grove near the Mission in 1920. It carried the following inscription (translated from Russian): "In the Year 1796, in the month of January, this bell was cast on the Island of Kodiak by the blessing of Archimandrite Joaseph, during the sojourn of Alexsandr Baranov." It is not known how this Russian Orthodox artifact from Kodiak, Alaska made its way to a Catholic mission in Southern California.

Gallery[]

A view looking down an exterior corridor at Mission San Fernando Rey de España, a common architectural feature of the Spanish Missions

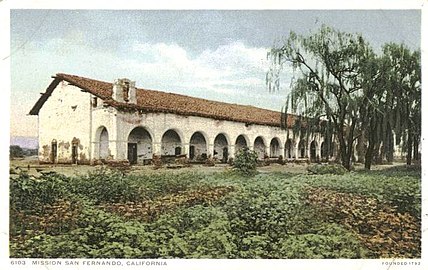

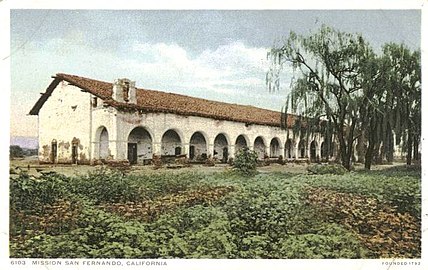

A view of the same colonnade as at left, circa 1900

The fountain opposite San Fernando Mission Boulevard

The present-day Mission façade

San Fernando Mission Church interior

A statue of Saint Father Junípero Serra and a native child at Mission San Fernando

Mission San Fernando Postcard, circa 1900

Lopez Station in the 1860s

See also[]

- Convento Building (Mission San Fernando)

- List of Spanish missions in California

- List of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments in the San Fernando Valley

- Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando

- San Fernando Mission Cemetery

- Spanish missions in California

- USNS Mission San Fernando (AO-122) – a Mission Buenaventura (AO‑111) Class fleet oiler built during World War I

- Casa De San Pedro served mission in past

- Chatsworth Calera owned by mission in past

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 49

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Krell, p. 263

- ^ Ruscin, p. 137

- ^ Yenne, p. 148

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ruscin, p. 196

- ^ Forbes, p. 202

- ^ Ruscin, p. 195

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Krell, p. 315: as of December 31, 1832; information adapted from Engelhardt's Missions and Missionaries of California.

- ^ Los Angeles Department of City Planning (September 7, 2007). "Historic – Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing: City Declared Monuments" (PDF). City of Los Angeles.

- ^ Bolton, Herbert E. (1927). Fray Juan Crespi: Missionary Explorer on the Pacific Coast, 1769–1774. HathiTrust Digital Library. p. 152.

- ^ Young, p. 39

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Engelhardt, Zephyrin (1897). The Franciscans in California. Harbor Springs, Mich., Holy childhood Indian school. pp. 411–412.

- ^ Englehardt 1897, p. 238

- ^ Jump up to: a b Englehardt 1897, p. 414

- ^ Jump up to: a b Englehardt 1897, p. 415

- ^ Bancroft, III, 645-646

- ^ Jump up to: a b Englehardt 1897, p. 416

- ^ Leon Worden. "California's REAL First Gold". www.scvhistory.com.

- ^ "Water and Power Associates". waterandpower.org.

- ^ "Mission San Fernando Rey de España". www.athanasius.com.

- ^ Davis, Mike City of Quartz London Vintage 1990 p.329 ISBN 0099998203

More information[]

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin, O.F.M. (1922). San Juan Capistrano Mission. Standard Printing Co., Los Angeles, CA.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Forbes, Alexander (1839). California: A History of Upper and Lower California. Smith, Elder and Co., Cornhill, London – via Internet Archive.

- Fedorova, Svetlana G., trans. & ed. by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly (1973). The Russian Population in Alaska and California: Late 18th Century – 1867. Limestone Press, Kingston, Ontario. ISBN 0-919642-53-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jones, Terry L. and Kathryn A. Klar (eds.) (2007). California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. Altimira Press, Landham, MD. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Krell, Dorothy (ed.) (1979). The California Missions: A Pictorial History. Sunset Publishing Corporation, Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 0-376-05172-8.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Paddison, Joshua (ed.) (1999). A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA. ISBN 1-890771-13-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Pauley, Kenneth E; Pauley, Carol M (2005). San Fernando, Rey de España: an illustrated history. Spokane: Arthur H. Clark Co. ISBN 978-0-87062-338-7.

- Ruscin, Terry (1999). Mission Memoirs. Sunbelt Publications, San Diego, CA. ISBN 0-932653-30-8.

- Wright, R. (1950). California's Missions. Hubert A. and Martha H. Lowman, Arroyo Grande, CA.

- Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. Thunder Bay Press, San Diego, CA. ISBN 1-59223-319-8.

- Young, S. & Levick, M. (1988). The Missions of California. Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco, CA. ISBN 0-8118-3694-0.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mission San Fernando Rey de España. |

- Official website

- Early photographs, sketches, land surveys of Mission San Fernando Rey de España, via Calisphere, California Digital Library

- Listing, photographs, and drawings of church at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Listing and photographs of fountains at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Listing, photographs, and drawings of monastery at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Howser, Huell (December 8, 2000). "California Missions (102)". California Missions. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive.

- Spanish missions in California

- 1797 in Alta California

- Roman Catholic churches in Los Angeles

- Museums in Los Angeles

- History museums in California

- Religious museums in California

- History of the San Fernando Valley

- Roman Catholic churches completed in 1797

- 18th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in the United States

- 1797 establishments in Alta California

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles

- California Historical Landmarks

- Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments

- National Historic Landmarks in California

- Churches on the National Register of Historic Places in California

- History of Los Angeles

- History of Los Angeles County, California

- Roman Catholic churches in California

- Buildings and structures in the San Fernando Valley

- Arcades (architecture)

- El Camino Viejo

- Butterfield Overland Mail in California

- Mission Hills, Los Angeles

- National Register of Historic Places in Los Angeles