Mixtec language

This article or section should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}} or {{transl}} (or {{IPA}} or similar for phonetic transcriptions), with an appropriate ISO 639 code. (July 2021) |

| Mixtec | |

|---|---|

| Mixteç | |

| Native to | Mexico |

| Region | Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero |

| Ethnicity | Mixtecs |

Native speakers | 530,000 in Mexico (2020 census)[1] |

Oto-Manguean

| |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Mexico |

| Regulated by | Academy of the Mixtec Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | (fifty-two individual codes) |

| Glottolog | mixt1427 |

Extent of the Mixtec languages: prior to contact (olive green) and current (red) | |

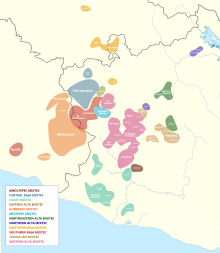

The distribution of various Mixtec languages and their classification per Glottolog | |

The Mixtec (/ˈmiːstɛk, ˈmiːʃtɛk/)[2] languages belong to the Mixtecan group of the Oto-Manguean language family. Mixtec is spoken in Mexico and is closely related to Trique and Cuicatec. The varieties of Mixtec are spoken by over half a million people.[3][4] Identifying how many Mixtec languages there are in this complex dialect continuum poses challenges at the level of linguistic theory. Depending on the criteria for distinguishing dialects from languages, there may be as few as a dozen[5] or as many as fifty-three Mixtec languages.[6]

Language name[]

The name "Mixteco" is a Nahuatl exonym, from mixtecatl, from mixtli [miʃ.t͡ɬi] ("cloud") + -catl [kat͡ɬ] ("inhabitant of place of").[7] Speakers of Mixtec use an expression (which varies by dialect) to refer to their own language, and this expression generally means "sound" or "word of the rain": dzaha dzavui in Classical Mixtec; or "word of the people of the rain", dzaha Ñudzahui (Dzaha Ñudzavui) in Classical Mixtec.

Denominations in various modern Mixtec languages include tu'un savi [tũʔũ saβi], tu'un isasi [tũʔũ isasi] or isavi [isaβi], tu'un va'a [tũʔũ βaʔa], tnu'u ñuu savi [tnũʔũ nũʔũ saβi], tno'on dawi [tnõʔõ sawi], sasau [sasau], sahan sau [sãʔã sau], sahin sau [saʔin sau], sahan ntavi [sãʔã ndavi], tu'un dau [tũʔũ dau], dahan davi [ðãʔã ðaβi], dañudavi [daɲudaβi], dehen dau [ðẽʔẽ ðau], and dedavi [dedavi].[8][which languages are these?]

Distribution[]

The traditional range of the Mixtec languages is the region known as La Mixteca, which is shared by the states of Oaxaca, Puebla and Guerrero. Because of migration from this region, mostly as a result of extreme poverty, the Mixtec languages have expanded to Mexico's main urban areas, particularly the State of México and the Federal District, to certain agricultural areas such as the San Quintín valley in Baja California and parts of Morelos and Sonora, and into the United States. In 2012, Natividad Medical Center of Salinas, California had trained medical interpreters bilingual in Mixtec as well as in Spanish;[9] in March 2014, Natividad Medical Foundation launched Indigenous Interpreting+, "a community and medical interpreting business specializing in indigenous languages from Mexico and Central and South America," including Mixtec, Trique, Zapotec, and Chatino.[10][11]

Internal classification[]

The Mixtec language is a complex set of regional dialects which were already in place at the time of the Spanish Conquest of the Mixteca region. The varieties of Mixtec are sometimes grouped by geographic area, using designations such as those of the Mixteca Alta, the Mixteca Baja, and the Mixteca de la Costa. However, the dialects do not actually follow the geographic areas, and the precise historical relationships between the different varieties have not been worked out.[12] The situation is far more complex than a simple dialect continuum because dialect boundaries are often abrupt and substantial, some likely due to population movements both before and after the Spanish conquest. The number of varieties of Mixtec depends in part on what the criteria are for grouping them, of course; at one extreme, government agencies once recognized no dialectal diversity. Mutual intelligibility surveys and local literacy programs have led SIL International to identify more than 50 varieties which have been assigned distinct ISO codes.[13] Attempts to carry out literacy programs in Mixtec which cross these dialect boundaries have not met with great success. The varieties of Mixtec have functioned as de facto separate languages for hundreds of years with virtually none of the characteristics of a single "language". As the differences are typically as great as between members of the Romance language family, and since unifying sociopolitical factors do not characterize the linguistic complex, they are often referred to as separate languages.

Phonology[]

This section describes the sound systems of Mixtec by each variety.

Chalcotongo Mixtec[]

The table below shows the phonemic inventory of a selected Mixtec language, Chalcotongo Mixtec.[14]

Phoneme[]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n, nᵈ | ɲ [j̃]1 | ||

| Stop | b | t | k, kʷ | ||

| Affricate | tʃ | ||||

| Fricative | s | ʃ, ʒ | x | ||

| Approximant | w | l | |||

| Tap | ɾ |

- 1Most commonly actually a nasalized palatal approximant.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ | u |

| Middle | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Not all varieties of Mixtec have the sibilant /s/. Some do not have the interdental fricative /ð/. Some do not have the velar fricative /x/. A few have the affricate /ts/. By some analyses, the sounds /m/ and /w/ ([β]) are allophones conditioned by nasalization (see below), as are /n/ and /nᵈ/, also /ɲ/ and /j/ ([ʒ]).

Tone[]

One of the most characteristic features of Mixtec is its use of tones, a characteristic it shares with all other Otomanguean languages. Despite its importance in the language, the tonal analyses of Mixtec have been many and quite different one from another. Some varieties of Mixtec display complex tone sandhi.[15] (Another Mixtecan language, Trique, has one of the most complex tonal systems in the world,[16] with one variety, Chicahuaxtla Trique, having at least ten tones and, according to some observers, as many as 16.)[17]

It is commonly claimed that Mixtec distinguishes three different tones: high, middle, and low. Tones may be used lexically; for example:

- Kuu [kùū] to be

- Kuu [kūù] to die

In some varieties of Mixtec, tone is also used grammatically since the vowels or whole syllables with which they were associated historically have been lost.

In the practical writing systems the representation of tone has been somewhat varied. It does not have a high functional load generally, although in some languages tone is all that indicates different aspects and distinguishes affirmative from negative verbs.

Nasalization[]

The nasalisation of vowels and consonants in Mixtec is an interesting phenomenon that has had various analyses. All of the analyses agree that nasalization is contrastive and that it is somewhat restricted. In most varieties, it is clear that nasalization is limited to the right edge of a morpheme (such as a noun or verb root), and spreads leftward until it is blocked by an obstruent (plosive, affricate or fricative in the list of Mixtec consonants). A somewhat more abstract analysis of the Mixtec facts claims that the spreading of nasalization is responsible for the surface "contrast" between two kinds of bilabials (/m/ and /β/, with and without the influence of nasalization, respectively), between two kinds of palatals (/ʒ/ and nasalized /j/—often less accurately (but more easily) transcribed as /ɲ/—with and without nasalization, respectively), and even two kinds of coronals (/n/ and /nᵈ/, with and without nasalization, respectively).[18] Nasalized vowels which are contiguous to the nasalized variants are less strongly nasalized than in other contexts. This situation is known to have been characteristic of Mixtec for at least the last 500 years since the earliest colonial documentation of the language shows the same distribution of consonants.

Glottalization[]

The glottalization of vowels (heard as a glottal stop after the vowel, and analyzed as such in early analyses) is a distinctive and interesting contrastive feature of Mixtec languages, as it is of other Otomanguean languages.[19]

Yoloxóchitl Mixtec[]

The sound system of Yoloxóchitl Mixtec (of Guerrero Mixtec) is described below.[20][21][22]

Sound inventory[]

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Labialised Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Stop & Affricate | p | t̪ | tʃ | k | kʷ | ||

| Pre-nasalised Stop | (ᵐb) | (ⁿd) | ᵑɡ | ||||

| Fricative | s̪ | ʃ | (x) | ||||

| Flap | (ɾ) | ||||||

| Approximant | β | l | j |

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i • ĩ | u • ũ | |

| Mid | e • ẽ | o • õ | |

| Open | a • ã |

Notes:

- The syllable structure is (C)V(V); no consonant cluster or consonant coda allowed.

- Oral and nasal vowels are contrastive.

Tone[]

Yoloxóchitl Mixtec has nine tones: /˥ ˦ ˨ ˩ ˥˧ ˥˩ ˧˩ ˨˦ ˩˧/.

Writing systems[]

The Mixtecs, like many other Mesoamerican peoples, developed their own writing system, and their codices that have survived are one of the best sources for knowledge about the pre-Hispanic culture of the Oaxacan region prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. With the defeat of the lordship of Tututepec in 1522, the Mixtecs were brought under Spanish colonial rule, and many of their relics were destroyed. However, some codices were saved from destruction, and are today mostly held by European collections, including the Codex Zouche-Nuttall and the Codex Vindobonensis; one exception is the Codex Colombino, kept by the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

The missionaries who brought the Roman Catholic religion to the Mixtecs set about learning their language and produced several grammars of the Mixtec language, similar in style to Antonio de Nebrija's Gramática Castellana. They also began work on transcribing the Mixtec languages into the Latin alphabet. In recent decades small changes in the alphabetic representation of Mixtec have been put into practice by the Academy of the Mixtec Language. Areas of particular interest include the following:

- The representation of the feature that distinguishes glottalized vowels (or glottal stop, as in some earlier analyses). Some earlier alphabets used h; more commonly today a special kind of apostrophe is used.

- The representation of the high central unrounded vowel. Some earlier alphabets used y; today a barred-i (ɨ) is used.

- The representation of the voiceless velar stop. Most earlier alphabets used c and qu, in line with earlier government policies; today k is more commonly used.

- The representation of tone. Most non-linguistic transcriptions of Mixtec do not fully record the tones. When tone is represented, acute accent over the vowel is typically used to indicate high tone. Mid tone is sometimes indicated with a macron over the vowel, but it may be left unmarked. Low tone is sometimes indicated with a grave accent over the vowel, but it might be left unmarked, or it might be indicated with an underscore to the vowel.

The alphabet adopted by the Academy of the Mixtec Language and later by the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP), contains the following letters (indicated below with their corresponding phonemes).

| Symbol | IPA | Example | Meaning | Approximate pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | a | andívi | sky | Similar to the English a in father |

| ch | tʃ | chitia | banana | Like English ch in chocolate |

| d | ð | de | he | Like English th in father |

| e | e | ve'e | home | Like Spanish e in este |

| g | ɡ | ga̱ | more | Like English g in go |

| i | i | ita̱ | flower | Like English i in machine |

| ɨ | ɨ | kɨni | pig | Like Russian ы or Romanian î |

| j | x | ji̱'in | shall drop | Like the j in Mexican Spanish |

| k | k | kúmi | four | Hard c, like English cool |

| l | l | luu | beautiful | Like Spanish l in letra |

| m | m | ña'ma̱ | shall confess | Like English m in mother |

| n | n | kuná'ín | shall cease | Like English n in no |

| nd | nᵈ | ita ndeyu̱ | orchid | Pronounced similar to an n followed by a slight non-nasal d-like transition to the oral vowel. |

| ng | ŋ | súngo̱o | to settle | Like English ng in eating |

| ñ | ɲ | ñuuyivi | world | Similar to Spanish ñ in caña, but typically without letting the tongue actually touch the hard palate. |

| o | o | chiso | sister-in-law | Similar to English o in toe |

| p | p | pi'lu | piece | Similar to English p in pin |

| r | ɾ | ru'u | I | Is sometimes trilled. |

| s | s | sá'a | cunningness | Like English s in sit |

| t | t | tájí | shall send | Like English t in tin |

| ts | ts | tsi'ina | puppy-dog | Like ț in Romanian or ц in Russian |

| u | u | Nuuyoo | Mexico | Like English u in tune |

| v | β | vilu | cat | Similar to Spanish v in lava |

| x | ʃ | yuxé'é | door | Like the initial sound in English shop |

| y | ʒ | yuchi | dust | Like English ge in beige |

| ' | ˀ | ndá'a | hand | When a vowel is glottalized it is pronounced as if it ends in a glottal stop. It is not uncommon for a glottalized vowel to have an identical but non-glottalized vowel after it. |

One of the main obstacles in establishing an alphabet for the Mixtec language is its status as a vernacular tongue. The social domain of the language is eminently domestic, since federal law requires that all dealings with the state be conducted in Spanish, even though the country's autochthonous languages enjoy the status of "national languages". Few printed materials in Mixtec exist and, up to a few years ago, written literature in the language was practically non-existent. There is little exposure of Mixtec in the media, other than on the CDI's indigenous radio system – XETLA and XEJAM in Oaxaca; XEZV-AM in Guerrero; and XEQIN-AM in Baja California – and a bilingual radio station based in the US in Los Angeles, California, where a significant Mixtec community can be found.

At the same time, the fragmentation of the Mixtec language and its varieties means that texts published in one variety may be utterly incomprehensible to speakers of another. In addition, most speakers are unaware of the official orthography adopted by the SEP and the Mixtec Academy, and some even doubt that their language can lend itself to a written form.

Grammar and syntax[]

Pronouns[]

Personal pronouns[]

Personal pronouns are richly represented in Mixtec.

| Person | Type | Independent | Dependent | Used for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person exclusive | Formal | sa̱ñá | ná | I (form.) |

| Informal | ru'u̱ | ri | I (inform.) | |

| 1st person inclusive | yó'ó | yó | we (incl.) | |

| 2nd person | Formal | ní'ín | ní | you (form.) |

| Informal | ró'ó | ró | you (inform.) | |

| 3rd person | de | he | ||

| ña | she | |||

| i | s/he (child) | |||

| ya̱ | s/he (god) | |||

| tɨ | it (animal) | |||

| te | it (water) |

First and second person pronouns[]

Many varieties (but not all) have distinct "formal" and "informal" pronouns for first person and second person (except in the first person plural inclusive). If addressing a person of his own age or older, the speaker uses the formal pronouns. If addressing a younger person, the speaker uses the informal pronouns. The first person exclusive pronouns may be interpreted as either singular or plural. The second person pronouns may also be interpreted as either singular or plural.

It is common to find a first person inclusive form that is interpreted as meaning to include the hearer as well as the speaker.

First and second person pronouns have both independent forms and dependent (enclitic) forms. The dependent forms are used when the pronoun follows a verb (as subject) and when it follows a noun (as possessor). The independent forms are used elsewhere (although there are some variations on this rule).

- Personal pronoun as direct object

Jiní

knows

de

3m

sa̱ñá

1.EX

"He knows me."

- Personal pronoun in preverbal position

Ró'ó

2

kí'i̱n

will.go

va̱'a

good

ga

more

"It will be better if you go."

- Personal pronoun in normal subject position

Va̱ni

well

nisá'a

did

ró

2

"You did well."

Third person pronouns[]

For the third person pronouns, Mixtec has several pronouns that indicate whether the referent is a man, a woman, an animal, a child or an inanimate object, a sacred or divine entity, or water. Some languages have respect forms for the man and woman pronouns. Some languages have other pronouns as well (such as for trees.) (These pronouns show some etymological affinity to nouns for 'man', 'woman', 'tree', etc., but they are distinct from those nouns.) These may be pluralized (in some varieties, if one wishes to be explicit) by using the common plural marker de in front of them, or by using explicit plural forms that have evolved.

Interrogative pronouns[]

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (January 2021) |

Mixtec has two interrogatives, which are na vé ([²na ³ve][what do the digits mean?] = "what/which"?) and nasaa ([²na.²saa]= "how much/many?"). The tone of these does not change according to the tense, person, or tone of the surrounding phrase.

Verbs[]

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (January 2021) |

Mixtec verb tenses[]

| Verb conjugation in Mixtec[what do the digits mean?] | ||||

| Future | Present | Past | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stéén [s.³teẽ] |

stéén [s.³teẽ] |

ni-steén [²ni s.²te³ẽ] |

to teach | |

| skáji [s.³ka.²xi] |

skáji [s.³ka.²xi] |

ni-skáji [²ni s.³ka.²xi] |

to feed | |

| skɨvɨ [s.³kɨ.²vɨ] |

skɨ́vɨ [s.³kɨ.²vɨ] |

ni-skɨ́vɨ [²ni s.³kɨ.²vɨ] |

to put | |

| stáan [s.³ta¹ã] |

stáan [s.³ta¹ã] |

ni-stáan [²ni s.³ta¹ã] |

to destroy | |

| ndukú [²ndu.³ku] |

ndúkú [³ndu.³ku] |

ni-ndukú [²ni ²ndu.³ku] |

to seek | |

| kunu [²ku.²nu] |

kúnu [³ku.²nu] |

ni-kunu [²ni ²ku.²nu] |

to sew | |

| kata [²ka.²ta] |

jíta [³ji.²ta] |

ni-jita [²ni ²ji.²ta] |

to sing | |

| kasɨ [²ka.²sɨ] |

jésɨ [³xe.²sɨ] |

ni-jésɨ [²ni ³xe.²sɨ] |

to close | |

| kua̱'a [²ku¹a'.²a] |

jé'e [²xe.²e] |

ni-je̱'e [²ni ¹xe'.²e] |

to give | |

| kusu̱ [²ku.¹su] |

kíxí [³ki.³ʃi] |

ni-kixi̱ [²ni ²ki.¹ʃi] |

to sleep | |

Mixtec verbs have no infinitive form. The basic form of the Mixtec verb is the future tense, and many conjugated future verb forms are also used for the present tense. To obtain the present of an irregular verb, the tone is modified in accordance with set of complicated prosodic rules. Another class of irregular verbs beginning with [k] mutate that sound to either [xe] or [xi] in the present tense. To form the preterite (past) tense, the particle ni- ([²ni]) is added. That particle causes a shift in the tone of the following verb and, while the particle itself may be omitted in informal speech, the tonal modification invariably takes place.

Mixtec lacks an imperfect, pluperfect, and all the compound tenses found in other languages. In addition, Mixtec verb conjugations do not have indicators of person or number (resembling, in this, English more than Spanish). A selection of Mixtec sentences exemplifying the three verbal tenses appears below:

- Future

Te

And

máá

same

ró

you

sanaa

perhaps

te

and

kusɨɨ ni

shall-be–happy

ro̱

you

te

and

kiji

shall-come

ró

you

ɨɨn

one

jínu

time

nájnu'un

as

domingu

Sunday

te

and

kinu'un

shall-return

ro̱.

you

"And perhaps you shall be happy, shall come on Sunday, and shall return home"

- Present

Tu

Not

jíní-yo̱

know-we

ndese

how

skánda-de

moves-he

te

and

jíka

advances

kamión

truck

"We don't know what he does to make the truck go"

- Preterite

Ni-steén-de

Past-taught-he

nuu̱

to

ná.

I

Steén-de

Taught-he

nuu̱

to

ná.

I

"He taught me"

Verb classes[]

- Causative verbs

Causative verbs are verb forms modified by a prefix indicating that the action is performed by the agent of the phrase. Mixtec causative verbs are indicated by the prefix s-. Like other Mixtec particles, the causative prefix leads to a shift in the orthography and pronunciation of the related verb. When the verb to which the prefix is added begins with [ⁿd], that phoneme is transformed into a [t]. Verbs beginning with [j] shift to [i]. There is no difference in future and present causative verbs, but the past tense is invariably indicated by adding the particle ni-.

| Regular causative | |

| Normal verb: tɨ̱vɨ́ shall-decompose It shall decompose, decomposes |

Causative verb: stɨ̱vɨ́ it–shall-decompose "He shall damage it, he damages it" |

| Irregular causative: nd → t shift | |

| Normal verb: ndo'o-ña shall-suffer–she She shall suffer, she suffer |

Causative verb: stó'o-ña shall-do–shall-suffer–she "She shall cause to suffer, she causes to suffer" |

| Irregular causative: y → i shift | |

| Normal verb: yu̱'ú-tɨ́ shall-fear–animal "The animal shall fear, the animal fears" |

Causative verb: siú'ú-tɨ́ shall-cause-fear–animal "The animal shall cause fear, the animal causes fear" |

- Repetitive verbs

The prefix na- indicates that the action of the related verb is being performed for a second occasion. This means that there is a repetition of the action, made by the subject of the sentence or another unidentified agent.

The pronunciation of some irregular verbs changes in the repetitive form. For example, certain verbs beginning with [k] take [ⁿd] o [n] the instead of na- particle. In addition, there are some verbs that never appear without this prefix: in other words, it is part of their structure.

| Regular repetitive verb | |

| Normal verb: Ki̱ku-ña shall-sew–she sa'ma clothes "She shall sew the clothes" |

Repetitive verb: Naki̱ku-ña again–shall-sew–she sa'ma clothes "She shall repair the clothes" |

| Regular repetitive verb: k → nd shift | |

| Normal verb: Kaa-de shall-ascend–he "He shall rise" |

Causative verb: Ndaa-de again–shall-ascend–he "He shall rise again" |

- Copulative verbs

Copulative verbs ("linking verbs") establish links between two nouns, a noun and an adjective, or a noun and a pronoun. Mixtec has four such verbs:

- kuu (to be)

- nduu (to be again; the repetitive form of kuu)

- koo (to exist)

- káá (to appear; present and preterite only)

Káá is only used with adjectives that describe a thing's appearance. The other three can be used with practically any adjective, albeit with slight semantic shifts.

| Copulative verbs | |

Maéstru Teacher kúu-te̱e is–man ún. a "The man is a teacher" |

Maestru Teacher kúu. is–man "He is a teacher" |

Ndíchí intelligent koo-ró shall-be–you "You will be intelligent" |

Va̱ni Good íyó is itu. crop "The crop is fine" |

Káa appears likuxi grey sɨkɨ̱ back tɨ̱. its-(animal's) The animal's back is grey" |

Kúká Rich ní-i̱yo-de. past–was-he "He was rich but is no longer" |

- Descriptive verbs

Descriptive verbs are a special class that can be used as either verbs or adjectives. One of these verbs followed by a pronoun is all that is needed to form a complete sentence in Mixtec. Descriptives are not conjugated: they always appear in the present tense. To give the same idea in the past or future tenses, a copulative verb must be used.

| Descriptive verbs | |

Kúká-de. shall-enrich-he "He is rich" |

Ve̱yɨ shall-weigh nuní. maize "The maize is heavy" |

| Descriptives with contracted copulas | |

Vijna now te and kúkúká-de. is-rich–he "Now he is rich" |

Ni-ndukuká-de. again–grew-rich–he "He became rich again" |

- Modal verbs

Modal verbs are a small group that may be followed by another verb. Only the relative pronoun jee̱ can occasionally appear between a modal and its associated verb, except in sentences involving kuu (can, to be able).

- Modal kuu ("can")

Kuu

can

ka'u-de

shall-read–he

tatu.

paper

"He will be able to read a book"

- Modal kánuú ("must")

Kánuú

must

je̱é

that

ki'ín-de.

shall-go–he

"He must go"

Verb moods[]

- Indicative mood

The indicative mood describes actions in real life that have occurred, are occurring, or will occur. The verb forms of the indicative mood are described above, in the section on verb tenses.

- Imperative mood

Imperatives are formed by adding the particle -ni to the future indicative form of the verb. In informal speech, the simple future indicative is frequently used, although the pronoun ró may be appended. There are three irregular verbs with imperative forms different from their future indicative. Negative imperatives are formed by adding the word má, the equivalent of "don't".

| Imperative mood | |||

| Formal | Informal | Negative | |

| Kaa̱n ní. "Speak!" |

Kaa̱n. "Speak!" |

Kaa̱n ro̱. "Speak!" |

Má kaa̱n ro̱. "Don't speak!" |

- Subjunctive mood

In Mixtec, the subjunctive mood serves as a mild command. It is formed by placing the particle na before the future form of the verb. When used in the first person, it gives the impression that the speaker closely reflects on the action before performing it.

| Third-person subjunctive | First-person subjunctive |

Na SJV kɨ́vɨ-de shall-enter–he ve'e. house "Let him enter the house" |

Na SJV kí'ín-na. shall-go–I "Then I shall go" |

- Counter-factual mood

The counter-factual mood indicates that the action was not performed or remained incomplete. To form the past counter-factual, ní is added and the tones of the verb change from preterite to present. A counter-factual statement not accompanied by a subordinate clause acquires the meaning "If only..." The particle núú can be added at the end of the main or subordinate clauses, should the speaker wish, with no change in meaning. Examples are shown below:

- Use of counter-factual verbs, formed by changing the tone of the past indicative.

Ní-jí'í-de

CNTF-PST-took–he

tajna̱

medicine

chi

and

je

already

ni-nduva̱'a-de.

past–cured–he

"If he had taken the medicine, he would be better by now"

- Use of a simple counter-factual sentence

Ní-jí'í-de

CNTF-PST–took–he

tajna̱.

medicine

"If only he had taken the medicine!"

- Use of a simple counter-factual sentence, with núú.

Ní-jí'í-de

CNTF-PST–took–he

tajna̱

medicine

núú.

CNTF

"If only he had taken the medicine!"

Núú

CNTF

ní-jí'í-de

CNTF-PST–took–he

tajna̱.

medicine

"If only he had taken the medicine!"

- Use of a simple counter-factual sentence, with núu (a conditional conjunction not to be confused with the mood particle described above)

Núu

if

ní-jí'í-de

CNTF-took–he

tajna̱.

medicine

CNTF

"If only he had taken the medicine!" Mismatch in the number of words between lines: 3 word(s) in line 1, 4 word(s) in line 2 (help);

- Use of a simple counter-factual with modal, in future tense

Kiji-de

CNTF-PST-shall-come

te

and

tu

not

ni-kúu.

past-can

"He was going to come, but was unable to"

Nouns[]

Nouns indicate persons, animals, inanimate objects or abstract ideas. Mixtec has few nouns for abstract ideas; when they do not exist, it uses verbal constructions instead. When a noun is followed by another in a sentence, the former serves as the nucleus of the phrase, with the latter acting as a modifier. In many such constructions, the modifier possesses the nucleus.

- Nouns as modifiers:

Ndu̱yu

stake

ka̱a

metal

"Nail"

- Modifiers possessing the nucleus of the phrase:

Ina

dog

te̱e

man

yúkuan

that

"That man's dog"

The base number of Mixtec nouns is singular. Pluralisation is effected by means of various grammatical and lexical tools. For example, a noun's number can be implicit if the phrase uses a plural pronoun (first person inclusive only) or if one of various verb affixes that modify the meaning are used: -koo and -ngoo (suffixes) and ka- (prefix). A third way to indicate a plural is the (untranslatable) particle jijná'an, which can be placed before or after verbs, pronouns, or nouns.

- Pluralisation indicated by the presence of the first-person-inclusive pronoun

Te

and

máá

same

yó-kúu

we-are

ñayuu

person

yúku

we-live

ndé

up-to

lugar

place

yá'a

this

"We are the ones who live in this place"

- Pluralisation with affixes: prefix ka- before the verb

Te

And

sukúan

so

kándo'o

PL-suffer

ñayuu

person

"In that way people suffer"

- Pluralisation with affixes: suffix -koo after the verb

Te

And

ni-kekoo

PST-arrived-PL

te̱e

man

ún

he

"The men arrived"

Demonstratives[]

Deictic adverbs are often used in a noun phrase as demonstrative adjectives.[24] Some Mixtec languages distinguish two such demonstratives, others three (proximal, medial, distal), and some four (including one that indicates something out of sight). The details vary from variety to variety, as do the actual forms. In some varieties one of these demonstratives is also used anaphorically (to refer to previously mentioned nominals in the discourse), and in some varieties a special anaphoric demonstrative (with no spatial use) is found. These demonstratives generally occur at the end of the noun phrase (sometimes followed by a "limiter"). The demonstratives are also used (in some varieties) following a pronominal head as a kind of complex pronoun.

Conjunctions[]

Conjunctions serve to join two words, two phrases, or two analogous sentences. Mixtec possesses twelve coordinating conjunctions and ten subordinating conjunctions.

- Coordinating conjunctions:

- te (and, but)

- te o (but)

- jíín (and)

- chi (because, and)

- chí (or)

- á... chí (either... or)

- ni... ni... (neither... nor)

- sa/sa su'va (but rather that)

- yu̱kúan na (then, so)

- yu̱kúan (so)

- je̱e yu̱kúan (for)

- suni (also)

- Subordinating conjunctions:

- náva̱'a (so that)

- je̱e (that)

- sɨkɨ je̱e (because)

- nájnu̱n (how)

- ve̱sú (although)

- núu (if)

- na/ níní na (when)

- ná/ níní (while)

- nde (until, since)

- kue̱chi (no more)

Word order in the clause[]

Mixtec is a verb–subject–object language. Variations in this word order, particularly the use of the preverbal position, are employed to highlight information.

Mixtec influence on Spanish[]

Perhaps the most significant contribution of the Mixtec language to Mexican Spanish is in the field of place names, particularly in the western regions of the state of Oaxaca, where several communities are still known by Mixtec names (joined with a saint's name): San Juan Ñumí, , Santa Cruz Itundujia, and many more. In Puebla and Guerrero, Mixtec place names have been displaced by Nahuatl and Spanish names. An example is (in Puebla), which is now known as Gabino Barreda.

Spanish words used in Mixtec languages are also those that were brought by the Spanish like some fruits and vegetables. An example is limun (in San Martin Duraznos Oaxaca), which is known as lemon (limón in Spanish), also referred to as tzikua Iya (sour orange).

Mixtec literature[]

Prior to the Spanish Conquest in the early 16th century, the native peoples of Mesoamerica maintained several literary genres. Their compositions were transmitted orally, through institutions at which members of the elite would acquire knowledge of literature and other areas of intellectual activity. Those institutions were mostly destroyed in the aftermath of the Conquest, as a result of which most of the indigenous oral tradition was lost forever. Most of the codices used to record historical events or mythical understanding of the world were destroyed, and the few that remain were taken away from the peoples that created them. Four Mixtec codices are known to survive, narrating the war exploits of the Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. Of these, three are held by European collections, with one still in Mexico. The key to deciphering these codices was rediscovered only in the mid-20th century, largely through the efforts of Alfonso Caso, as the Mixtec people had lost the understanding of their ancient rules of reading and writing.

However, the early Spanish missionaries undertook the task of teaching indigenous peoples (the nobility in particular) to read and write using the Latin alphabet. Through the efforts of the missionaries and, perhaps more so, of the Hispanicized natives, certain works of indigenous literature were able to survive to the modern day. Of the half-dozen varieties of Mixtec recognized in the 16th century, two in particular were preferred for writing, those of Teposcolula/Tilantongo and Achiutla/Tlaxiaco in Mixteca Alta.[25] Over the five centuries that followed the Conquest, Mixtec literature was restricted to the popular sphere. Through music or the way in which certain rituals are carried out, popular Mixtec literature has survived as it did for millennia: by means of oral transmission.

It was not until the 1990s that indigenous literature in Mexico took off again. At the vanguard were the Zapotecs of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, who had been recording their language in writing since at least the mid-19th century. Imitating the great cultural movement of the indigenous people of Juchitán de Zaragoza in the 1980s, many native cultures reclaimed their languages as literary vehicles. In 1993 the was created and, three years later, the . At the same time, the for indigenous language literature was created, in order to promote writing in Native American tongues.

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In the Mixteca region, the literary renaissance has been led by the peoples of the Mixteca Alta, including the cities of Tlaxiaco and Juxtlahuaca. The former has produced such notable writers as , who published works by several Mixtec poets in the book Asalto a la palabra, and , who in addition to collecting the region's lyrical compositions has also produced notable pieces of his own, such as Yunu Yukuninu ("Tree, Hill of Yucuninu"). That piece was later set to music by Lila Downs, one of the leading figures in contemporary Mixtec music; she has recorded several records containing compositions in Mixtec, a language spoken by her mother.

See also[]

- Classification of Mixtec languages

- Indigenous languages of the Americas

- Languages of Mexico

- Mixtec (indigenous peoples of Mexico)

- Oto-Manguean languages

- Technological University of the Mixteca

- Trique language

Notes[]

- ^ Lenguas indígenas y hablantes de 3 años y más, 2020 INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020.

- ^ "Mixtec". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ 2000 census; the numbers are based on the number of the total population for each group and the percentages of speakers given on the website of the Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, http://www.cdi.gob.mx/index.php?id_seccion=660, accessed 28 July 2008).

- ^ "Tabulados Interactivos-Genéricos". www.inegi.org.mx. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Campbell 1997:402)

- ^ INALI, 2008: Segunda sección 84-Tercera sección 3)

- ^ Melissa Flores (2012-01-23). "Salinas hospital to train indigenous-language interpreters". HealthyCal.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ "Natividad Medical Foundation Announces Indigenous Interpreting+ Community and Medical Interpreting Business". Market Wired. 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ Almanzan, Krista (2014-03-27). "Indigenous Interpreting Program Aims to be Far Reaching". 90.3 KAZU. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ See Josserand (1983) for one important attempt. Adaptations of Josserand's dialect maps are published in Macaulay 1996.

- ^ "Ethnologue name language index", Ethnologue web site, accessed 28 July 2008.

- ^ Macauley, Monica (1996). A grammar of Chalcatongo Mixtec. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 12.

- ^ McKendry (2001)

- ^ Hollenbach (1984)

- ^ Longacre (1957)

- ^ Marlett (1992), McKendry (2001)

- ^ Macaulay and Salmons (1995)

- ^ DiCanio, C. T., Zhang, C., Whalen, D. H., & García, R. C. (2019). Phonetic structure in Yoloxóchitl Mixtec consonants. Journal of the International Phonetic Association. doi:10.1017/S0025100318000294

- ^ DiCanio, C. T., Amith, J., & García, R. C. (2012). Phonetic Alignment in Yoloxóchitl Mixtec Tone. Presented at the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas (SSILA).

- ^ DiCanio, Christian & Ryan Bennett. (To appear). Prosody in Mesoamerican Languages (pre-publication version). In C. Gussenhoven & A. Chen (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Language Prosody.

- ^ Alexander (1980:57ff)

- ^ Bradley and Hollenbach (1988, 1990, 1991, 1992).

- ^ Terraciano (2004) The Mixtecs of Colonial Oaxaca: Ñudzahui History, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries

- "Estadística básica de la población hablante de lenguas indígenas nacionales 2015". site.inali.gob.mx. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

References[]

- Bradley, C. Henry & Barbara E. Hollenbach, eds. 1988, 1990, 1991, 1992. Studies in the syntax of Mixtecan languages, volumes 1–4. Dallas, Texas: Summer Institute of Linguistics; [Arlington, Texas:] University of Texas at Arlington.

- Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian languages: the historical linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (2008). Catálogo de Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales. Diario Oficial de la Nación, January 14.

- Jiménez Moreno, Wigberto. 1962. Estudios mixtecos. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional Indigenista (INI); Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). (Reprint of the introduction to the Vocabulario en lengua mixteca by Fray Francisco de Alvarado.)

- Josserand, Judy Kathryn. 1983. Mixtec Dialect History. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tulane University.

- Macaulay, Monica & Joe Salmons. 1995. The phonology of glottalization in Mixtec. International Journal of American Linguistics 61(1):38-61.

- Marlett, Stephen A. 1992. Nasalization in Mixtec languages. International Journal of American Linguistics 58(4):425-435.

- McKendry, Inga. 2001. Two studies of Mixtec languages. M.A. thesis. University of North Dakota.

External links[]

| Mixtec language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Technological University of the Mixteca

- Spanish–Mixtec dictionary AULEX (Mexico)

- Comparative Mixtec Swadesh vocabulary list (from Wiktionary)

- SEP textbook in Guerrero Mountain Mixtec

- Mixtec family (SIL-Mexico)

- Resources for certain varieties of Mixtec

- Digital edition of Josserand (1983) at AILLA (requires creation of free account)

- Mixtec language

- Guerrero

- Oaxaca

- Puebla

- Analytic languages

- Isolating languages