Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari

Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari | |

|---|---|

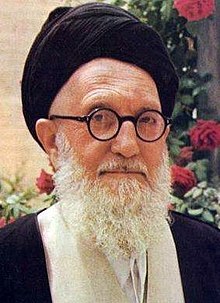

Shariatmadari, March 1982 | |

| Title | Grand Ayatollah |

| Personal | |

| Born | 5 January 1906 Tabriz, Persia |

| Died | 3 April 1986 (aged 80) |

| Religion | Islam |

| Ethnicity | Azeri |

| Era | Modern history |

| Creed | Usuli Twelver Shia Islam |

Sayyid Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari (Persian: محمد کاظم شریعتمداری), also spelled Shariat-Madari (5 January 1906 – 3 April 1986), was an Iranian Grand Ayatollah. He favoured the traditional Shiite practice of keeping clerics away from governmental positions and was a critic of Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini, denouncing the taking hostage of diplomats at the US embassy in Tehran.[1]

After coming to power in Iran, Khomeini intended to put to a referendum the draft constitution he had previously drafted, contrary to the promises he had made to the people in France, but Ayatollah Shariatmadari strongly opposed Khomeini's unjust and oppressive actions. He called for the draft constitution to be drafted in a democratic manner and in a parliament composed of representatives of the nation. Khomeini opposed the formation of the Constituent Assembly on the pretext of lack of time. But after the public protest of the people and members of the interim government and the prime minister, on the recommendation of Mahmoud Taleghani, he decided to form the Assembly of Experts. To review this draft within a month. And then put to a public referendum.Until Seyyed Mahmoud Taleghani died suspiciously on 19th of shahrivar And saved Khomeini, who was confused about how to raise the absolute authority of the jurist in the Assembly of Experts. On Shahrivar 21th, Khomeini tried to legally incorporate the principle of authority of jurisprudent into the constitution. And when the members of the Assembly of Experts refused to approve it, he declared to the deputies that those who are not jurists have no right to comment on this principle. But the groundwork for the passage of this disgraceful law, which gave the nation's rights to the Supreme Leader, was not hidden from Shariatmadari and was met with a backlash. He declared that Articles 105 and 110 of the Constitution should be changed. He considered Velayat-e-Faqih against the principle of the sovereignty of the nation and explicitly demanded the recognition of nationalities and the limitation of the powers of the Supreme Leader.In an interview with Swiss television, Shariatmadari said:"There is Velayat-e Faqih, but this Velayat has some limits, and in the meantime the power of the nation and the sovereignty of the people should not be forgotten, because in Iran the referendum that voted for the Islamic Republic means that the power belongs to the nation and the elections of the Assembly of Experts and its representatives It was the people's vote and it has become clear that they are now in the Assembly of Experts to speak on behalf of the nation. So, originality is with the nation, Even when the National Assembly and the presidency are to be elected by the people, it is another reason for the national government, so the principle of Velayat-e-Faqih should not be interpreted differently. Velayat-e-Faqih should never be interpreted as a dictatorship".

However, this disputed principle was added to the constitution with Khomeini's terrorization mean while the invalidation of the vote of the non-jurist representatives of the Assembly of Experts, and was put to a referendum on 11 and 12 Azar. But Shariatmadari issued a statement opposing the inclusion of this principle in the constitution and protesting against the questioning of national sovereignty in the constitution. Instead of broadcasting the proclamation of Shariatmadari , the Islamic Republic Radio and Television broadcast a declaration of Abdul Rasool Shariatmadari a lowly cleric who called for the people to take part in the constitutional referendum , while broadcasting a picture of Ayatollah Shariatmadari.

The deception and seduction of government officials sparked widespread protests in East and West Azerbaijan, especially in the cities of Tabriz, Urmia, and Qom, where Ayatollah Shariatmadari was based.

Following the provocations of the known elements, on the night of Thursday, Azar 14th, 1358, some people attacked armedly the house of Ayatollah Shariatmadari. They targeted and killed a guard named Ali Rezaei, who was guarding on the roof of the house of Ayatollah Shariatmadari.

After this incident, Khomeini opportunistically attributed the crime to foreign agents instead of apologizing!

This exacerbated the seizures. The protests continued until the next month . Finally, in Tabriz, government centers and "Radio and Television", the region and the air base were seized by angry people. Khomeini rushed to meet with Shariatmadari, and Shariatmadari, who had a peaceful spirit, issued a statement calling for peace to prevent bloodshed. He called on the Azerbaijani people to end the conflict and remain silent. Following the evacuation of the offices on the orders of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, government forces led by Mousavi Tabrizi attacked the offices of the Muslim People's Party, arrested many of its activists, and hanged some of them at the behest of Mousavi Tabrizi.

His followers also opposed Ruhollah Khomeini.

Biography[]

Early life and education[]

Born in Tabriz in 1906, According to the 15th of December 1284 AH, he was born in Amirkhiz neighborhood of Tabriz. His father, Ayatollah Seyyed Hassan Shariatmadari, was one of the scholars of Tabriz who died in 1292 AH.His grandfather, Haj Seyyed Mohammad Boroujerdi, was a noble Sadat. Who was transferred to Tabriz in 1270 AH and formed a family. It is said that the government of Boroujerd had a quarrel with him and ordered him to be arrested. The agents came but did not dare to arrest him, until that night the ruler died of a heart attack. Their noble lineage leads to Imam Zin al-Abedin (as). One of his ancestors is Abu al-Qasim Ja'far ibn Hussein ibn Ali ibn Hassan Makfuf ibn Hassan Aftas ibn Ali Asghar ibn Imam Zayn al-Abidin, who is known as the Imamzadeh Ja'far in Boroujerd and has a famous tomb.

Shariatmadari was among the most senior leading Twelver Shia clerics in Iran and Iraq and was known for his forward looking and liberal views.[2] After the death of Supreme and Grand Ayatollah Borujerdi (Marja' Mutlaq) in 1961 he became one of the leading marjas, with followers in Iran, Pakistan, India, Lebanon, Kuwait and the southern Persian Gulf states.[3]

In 1963, he prevented the Shah from executing Ayatollah Khomeini by recognizing him as a Grand Ayatollah, since according to the Iranian constitution a Marja' could not be executed. Khomeini was exiled instead. As the leading Mujtahid he was the head of Qom's seminary until Khomeini's arrival.[4] He was in favour of the traditional Shiite view of keeping clerics away from governmental positions and a vehement critic of Khomeini. He headed the Centre for Islamic Study and Publications and was the administrator of the Dar al-Tabligh and the Fatima Madrasa in Qom.

Following the demonstrations by religious dissidents in Qom in January 1978 the Shah's security forces opened fire and six people were killed.[1] Shariatmadari condemned the killings and called for the return of Ayatollah Khomeini.[1] He congratulated Khomeini's return, sending him a letter on 4 February 1979.[5]

Clash with Khomeini[]

Shariatmadari was at odds with Khomeini's interpretation of the concept of the "Leadership of Jurists" (Wilayat al-faqih), according to which clerics may assume political leadership if the current government is found to rule against the interests of the public. Contrary to Khomeini, Shariatmadari adhered to the traditional Twelver Shiite view, according to which the clergy ought to serve society and remain aloof from politics. Furthermore, Shariatmadari strongly believed that no system of government can be coerced upon a people, however morally correct it may be. Instead, people need to be able to freely elect a government. He believed a democratic government where the people administer their own affairs is perfectly compatible with the correct interpretation of the Leadership of the Jurists.[6] Before the revolution, Shariatmadari wanted a return to the system of constitutional monarchy that was enacted in the Iranian Constitution of 1906.[7] He encouraged peaceful demonstrations to avoid bloodshed.[8] According to such a system, the Shah's power was limited and the ruling of the country was mostly in the hands of the people through a parliamentary system. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the then Shah of Iran, and his allies, however, took the pacifism of clerics such as Shariatmadari as a sign of weakness. The Shah's government declared a ban on Muharram commemorations hoping to stop revolutionary protests. After a series of severe crack downs on the people and the clerics and the killing and arrest of many, Shariatmadari criticized the Shah's government and declared it non-Islamic, tacitly giving support to the revolution hoping that a democracy would be established in Iran.[9]

On 26 November 1979 Shariatmadari denounced the occupation of the US embassy in Tehran.[1] He also criticized Khomeini's system of government as not being compatible with Islam or representing the will of the Iranian people. He severely criticized the way that a referendum was conducted to establish Khomeini's system of government.[10] This led Khomeini to put him under house arrest, imprison his family members and torture his daughters-in-law. This led to mass protests in Tabriz which were quashed toward the end of January 1980, when under the orders of Khomeini tanks and the army moved into the city. Shariatmadari, not wanting an internal civil war or armed fighting and unnecessary killing of fellow Shiites, ordered a stop to the protests.

In April 1982, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh was arrested on charges of plotting with military officers and clerics to bomb Khomeini's home and to overthrow the state. Ghotbzadeh denied any intentions on Khomeini's life and claimed he had sought to change the government, not overthrow the Islamic Republic. He, under torture, also implicated Ayatollah Shariatmadari, who, he claimed, had been informed of the plan and had promised funds and his blessings if the scheme succeeded. However, the confession, extracted under torture, did not match with Shariatmadari's character and views as a pacifist. Shariatmadari's son-in-law, who was accused of serving as an intermediary between Ghotbzadeh and the Ayatollah, was sentenced to a prison term and a propaganda campaign was mounted to discredit Shariatmadari. Shariatmadari family members were arrested and tortured. According to a new book containing the memoirs of Mohammad Mohammadi Rayshahri, a leading player in the Iranian government and the head of the Hadith University in Iran, the Ayatollah himself was beaten by Rayshahri.[11] All this forced the aging Ayatollah to go on national television and read out a confession and ask forgiveness from the man he had saved from death two decades ago. Because of his position as a mujtahid, the government could not publicly execute him. His Centre for Islamic Study and Publications was closed and he remained under house arrest until his death in 1986. He is buried in a simple grave in a cemetery in Qom. Clerics were prevented from attending his funeral prayer, drawing criticisms from Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri, one of the lead players in the Iranian revolution.

Further reading[]

- Fischer, Michael M. J. (2003). Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Moojan Momen. bahaipedia.org. Yale University Press. 1986.

- Bakhash, Shaul (4 June 1990). Reign of the Ayatollahs. ISBN 0-465-06887-1.

- Keddie, Nikki (2003). Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution. Yale University Press.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nikazmerad, Nicholas M. (1980). "A Chronological Survey of the Iranian Revolution". Iranian Studies. 13 (1/4): 327–368. doi:10.1080/00210868008701575. JSTOR 4310346.

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. xxxiv-xxxv.

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 63, 88 (describing the system of education and main scholars of Qom just before the revolution).

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, p. 196

- ^ Sahimi, Mohammad (3 February 2010). "The Ten Days That Changed Iran". FRONTLINE. Los Angeles: PBS. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, p. 154

- ^ Kraft, Joseph (18 December 1978). "Letter from Iran". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 194–202

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 194–195

- ^ Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, pp. 221–222

- ^ Mohammad Mohammadi Raishahri, Khaterat (Memoire), vol.2

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari. |

- 1906 births

- 1986 deaths

- People from Tabriz

- Iranian Azerbaijani grand ayatollahs and clerics

- Muslim People's Republic Party politicians

- People of the Iranian Revolution

- Iranian revolutionaries

- People who have been placed under house arrest in Iran

- Deaths from kidney cancer

- Deaths from cancer in Iran

- Iranian grand ayatollahs

- Iranian dissidents