Monastic community of Mount Athos

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

| |

| Common languages | Languages:[1] Greek (main language) English ("quite widely spoken") Bulgarian (in Zograf) Romanian (in Lakkoskiti and Prodromos) Russian (in St. Panteleimon) Serbian (in Hilandar) |

|---|---|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Autonomous theocratic society led by an ecclesiastical council |

• Ecumenical Patriarch | Bartholomew I |

• Protepistate | Elder Symeon of Dionysiou[2] |

| Athanasios Martinos[3] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 336 km2 (130 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2011[4] estimate | 2,416 |

| Currency | Euro |

Website http://mountathosinfos.gr/ | |

| Today part of | Greece |

The monastic community of Mount Athos is an Eastern Orthodox community of monks living on the Mount Athos peninsula in Northern Greece.

The community includes 20 monasteries and the settlements that depend on them. The monasteries house around 2,000 Eastern Orthodox Greek, Bulgarian, Romanian, Russian, Serbian and other monks.

Women and most female animals are banned from the Mount Athos by religious tradition of the community which lives there.[5]

Political structure[]

A territory of Greece, the monastic community enjoys autonomous self-government. The Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs manages relations between the monastic community and the Government of Greece.

The territory of the monastic community is contiguous with Stagira-Akanthos, separated by a fence about 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) in length. Karyes is the administrative center and the seat of the synod and of the Civil Administrator of Mount Athos with his staff of lay people in the service of the monastic community.

The monasteries of the monastic community are stauropegic; they are exempt from the authority of the local bishop and only report to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

Administration and organization[]

According to the constitution of Greece, the territory of the monastic community which is "[t]he Athos peninsula extending beyond Megali Vigla and constituting the region of Aghion Oros" is, "following ancient privilege", "a self-governed part of the Greek State, whose sovereignty thereon shall remain intact". The constitution also states that "[a]ll persons leading a monastic life thereon acquire Greek citizenship without further formalities, upon admission as novices or monks." The constitution states "[h]eterodox or schismatic persons" are forbidden to stay on the territory. The community consists of 20 main monasteries which constitute the Holy Community.[6] Karyes is home to a civil administrator as the representative of the Greek state. The governor is an executive appointee.

The monastic community is under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew I.

Administration[]

The monastic community is governed by the "Sacred Community" (Ιερά Κοινότητα – Iera Koinotēta). It consists of representatives from the monasteries. There is a four-man executive committee, the "Sacred Administration" (Ιερά Επιστασία – Iera Epistasia), with the protos (Πρώτος) being its head.

Civil authorities are represented by the civil administrator, appointed by the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He supervises the function of the institutions and the public order.

Each of the 20 monasteries is administered by an archimandrite elected by the monks for life. The Convention of the brotherhood (Γεροντία) is the legislative body. Each of the other establishments (sketes, cells, huts, retreats, and hermitages) is a dependency of one of the 20 monasteries and is assigned to the monks by a document called omologon (ομόλογον).

Monks[]

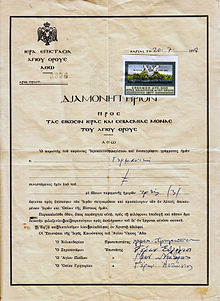

All persons leading a monastic life in the monastic community receive Greek citizenship upon admission as novices or monks. Laymen can visit the monastic community, but they need a special permit known as a diamonētērion (διαμονητήριον)

In 17 of the monasteries, the monks are predominantly ethnic Greek. The Helandariou Monastery is Serbian, the Zografou Monastery is Bulgarian and the Agiou Panteleimonos monastery is Russian.

Most of the sketes are also predominantly ethnic Greek; however, two sketes are Romanian. They are the coenobitic "Skētē Timiou Prodromou" (under Megistis Lavras Monastery) and the idiorrhythmic "Skētē Agiou Dēmētriou tou Lakkou", also called "Lakkoskētē" (under to the Agiou Pavlou monastery). A third skete is Russian, "Skētē Bogoroditsa" (under the Agiou Panteleimonos monastery).

The Greek language is commonly used in all the Greek monasteries, but in some monasteries there are other languages in use: in Agiou Panteleimonos, Russian (67 monks in 2011); in Helandariou Monastery, Serbian (58); in Zographou Monastery and Skiti Bogoroditsa, Bulgarian (32); and in Timiou Prodromou and Lakkoskiti, Romanian (64). Today, many of the Greek monks also speak foreign languages. Since there are monks from many nations in Athos, they naturally also speak their own native languages.

History[]

World War II[]

During the 1941 German invasion of Greece, Time magazine described a bombing attack near the monastic community, "The Stukas swooped across the Aegean skies like dark, dreadful birds, but they dropped no bombs on the monks of Mount Athos".[7]

During the German occupation of Greece, the Epistassia formally asked Adolf Hitler to place the monastic community under his personal protection. Hitler agreed and received the title "High Protector of the Holy Mountain" (German: Hoher Protektor des heiligen Berges) from the monks. The monastic community was able to avoid significant damage during the war.[8][better source needed]

Post-war[]

After the war, a Special Double Assembly passed the constitutional charter of the monastic community, which was then ratified by the Greek Parliament.

In 2018, the monastic community became an issue in Greece-Russia relations when the Greek government denied entry to Russian clerics headed for the monastic community. The media reported allegations that the Russian Federation was using the monastic community as a base for intelligence operations in Greece.[9]

Relations with Russia worsened in October 2018 after the Russian Orthodox Church banned its adherents from visiting sites controlled by Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople, including the monastic community.[10]

Monastic life[]

The monasteries of Mount Athos have a history of opposing ecumenism, or movements towards reconciliation between the Orthodox Church of Constantinople and the Catholic Church. The Esphigmenou monastery is particularly outspoken in this respect, having raised black flags to protest against the meeting of Patriarch Athenagoras I of Constantinople and Pope Paul VI in 1972. Esphigmenou was subsequently expelled from the representative bodies of the Athonite Community. The conflict escalated in 2002 with Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople declaring the monks of Esphigmenou an illegal brotherhood and ordering their eviction; the monks refused to be evicted, and the Patriarch ordered a new brotherhood to replace them.

The monasteries also have opposed ecumenism between the Orthodox Church of Constantinople and Oriental Orthodox Churches. Following the First[11] and Second[12] Agreed Statements published by the in 1989 and 1990 respectively, and the subsequent Proposals for Lifting Anathemas[13] in 1993, a committee formed by the monasteries published a responding memorandum expressing their condemnation of what they perceived to be an imminent false union with "the Non-Chalcedonians".[14]

After reaching a low point of just 1,145 mainly elderly monks in 1971, the monasteries have been undergoing a steady and sustained renewal. By the year 2000, the monastic population had reached 1,610, with all 20 monasteries and their associated sketes receiving an infusion of mainly young, well-educated monks. In 2009, the population stood at nearly 2,000.[15] Many younger monks possess university education and advanced skills that allow them to work on the cataloging and restoration of the Mountain's vast repository of manuscripts, vestments, icons, liturgical objects and other works of art, most of which remain unknown to the public because of their sheer volume. Projected to take several decades to complete, this restorative and archival work is funded by UNESCO and the EU, and aided by many academic institutions. The history of the modern revival of monastic life on Mount Athos and its entry into the technological world of the twenty-first century has been chronicled in Graham Speake's book, now in its second edition, Mount Athos. Renewal in Paradise.[16]

Monasteries[]

A pilgrim/visitor to a monastery who is accommodated in the guest-house (αρχονταρίκι) can have a taste of the monastic life in it by following its daily schedule: praying (services in church or in private), common dining, working (according to the duties of each monk) and rest. During religious celebrations, long vigils are typically held and the daily program is dramatically altered. The gate of the monastery closes by sunset and opens again by sunrise.

Cells[]

A cell is a house with a small church where 1–3 monks live under the supervision of a monastery. Usually, each cell possesses a piece of land for agricultural or other use. Each cell has to organize some activities for income.

Sketes[]

Small communities of neighbouring cells have developed since the beginning of monastic life in the monastic community, some of which using the word "skete" (σκήτη) meaning "monastic settlement" or "lavra" (λαύρα) meaning "monastic congregation". The word "skete" is of Coptic origin and in its original form is a placename of a location in the Egyptian desert.[17]

List of religious institutions[]

Twenty monasteries[]

The sovereign monasteries, in the order of their place in the Athonite hierarchy:

| Great Lavra monastery | Vatopedi monastery | Iviron monastery | Helandariou monastery | Dionysiou monastery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Μεγίστη Λαύρα | Βατοπέδι | Ιβήρων ივერთა მონასტერი (Georgian) |

Χιλανδαρίου Хиландар (Serbian) |

Διονυσίου |

|

|

|

|

|

| Koutloumousiou monastery | Pantokratoros monastery | Xeropotamou monastery | Zografou monastery | Docheiariou monastery |

| Κουτλουμούσι | Παντοκράτορος | Ξηροποτάμου | Ζωγράφου Зограф (Bulgarian) |

Δοχειαρίου |

|

|

|

|

|

| Karakalou monastery | Filotheou monastery | Simonos Petras monastery | Agiou Pavlou monastery Mănăstirea Sfântul Pavel (Romanian) |

Stavronikita monastery |

| Καρακάλλου | Φιλοθέου | Σίμωνος Πέτρα | Αγίου Παύλου | Σταυρονικήτα |

|

|

|

|

|

| Xenophontos monastery | Osiou Grigoriou monastery | Esphigmenou monastery | Agiou Panteleimonos monastery

Пантелеймонов (Russian) |

Konstamonitou monastery |

| Ξενοφώντος | Οσίου Γρηγορίου | Εσφιγμένου | Αγίου Παντελεήμονος | Κωνσταμονίτου |

|

|

|

|

|

Twelve sketes[]

A skete is a community of Christian hermits following a monastic rule, allowing them to worship in comparative solitude, while also affording them a level of mutual practical support and security. There are two kinds of sketes in Mount Athos. A coenobitic skete follows the style of monasteries. An idiorrhythmic skete follows the style of a small village: it has a common area of worship (a church), with individual hermitages or small houses around it, each one for a small number of occupants. There are twelve official sketes on Mount Athos.

| Skete | Type | Monastery | Alternative names / notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agias Annas

Αγίας Άννας |

Idiorrhythmic | Megistis Lavras | (= Saint Anne)

Agiánna |

| Agias Triados or

Αγίας Τριάδος ή Καυσοκαλυβίων |

Idiorrhythmic | Megistis Lavras | (= Holy Trinity)

Kafsokalývia (="burned huts") |

| Timiou Prodromou

Τιμίου Προδρόμου |

Coenobitic | Megistis Lavras | (= Holy Fore-runner, i.e. St John the Baptist)

Prodromu, Sfântul Ioan Botezătorul – Romanian |

| Agiou Andrea

Αγίου Ανδρέα |

Coenobitic | Vatopediou | (= Saint Andrew)

Also known as Saray (Σαράι) |

|

Αγίου Δημητρίου |

Idiorrhythmic | Vatopediou | (= Saint Demetrius)

Vatopediní |

|

Τιμίου Προδρόμου Ιβήρων |

Idiorrhythmic | Iviron | (= Holy Forerunner, i.e. St John the Baptist)

Ivirítiki |

| Agiou Panteleimonos

Αγίου Παντελεήμονος |

Idiorrhythmic | Koutloumousiou | (= Saint Panteleimon/Pantaleon)

Koutloumousianí |

| Profiti Ilia

Προφήτη Ηλία |

Coenobitic | Pantokratoros | (= Prophet Elijah) |

| Theotokou or Nea Skiti

Θεοτόκου ή Νέα Σκήτη |

Idiorrhythmic | Agiou Pavlou | (=Of God-Bearer or New Skete) |

| Agiou Dimitriou tou Lakkou or Lakkoskiti

Αγίου Δημητρίου του Λάκκου ή Λακκοσκήτη |

Idiorrhythmic | Agiou Pavlou | (= Saint Demetrius of the Ravine or Ravine-Skete)

Lacu, Sfântul Dumitru – Romanian |

| Evangelismou tis Theotokou

Ευαγγελισμού της Θεοτόκου |

Idiorrhythmic | Xenophontos | (= Annunciation of Theotokos)

Xenofontiní |

| Bogoroditsa

Βογορόδιτσα |

Coenobitic | Agiou Panteleimonos |

Main settlements[]

- Karyes

- Dafni

Culture[]

Prohibition on entry of women[]

The monastic community bans women and female animals from entry in what is called an avaton (Άβατον). This intended to make living in celibacy easier for men who have chosen to do so.[18]

The ban was officially proclaimed by several emperors, including Constantine Monomachos, in a chrysobull of 1046.[19]

In the 14th century, Serbian Emperor Dušan the Mighty brought his wife, Helena of Bulgaria, to the monastic community to protect her from the plague. She avoided breaking the ban by not touching the ground for her entire visit, being constantly carried in a hand carriage.[20]

Maryse Choisy entered the monastic community in the 1920s disguised as a sailor. She later wrote about her escapade in Un mois chez les hommes ("A Month with Men").[21]

In the 1930s, Aliki Diplarakou dressed as a man and snuck into the monastic community. Her stunt was discussed in a 13 July 1953 Time magazine article entitled "The Climax of Sin".[22]

In 1953, Cora Miller, an American Fulbright Program teacher, landed briefly along with two other women, stirring up a controversy among the local monks.[23]

A 2003 resolution of the European Parliament requested the lifting of the ban for violating "the universally recognised principle of gender equality".[24]

On 26 May 2008, five Moldovans illegally entered Greece by way of Turkey, ending up in the monastic community. Four of these migrants were women. The monks forgave them for trespassing and informed them that the area was forbidden to females.[25]

Female domestic animals such as cows or sheep are also barred, except for female cats.[26]

Status in the European Union[]

As part of an EU member state, Mount Athos is part of the European Union and, for the most part, subject to EU law. While outside the EU's Value Added Tax area, Mount Athos is within the Schengen Area. A declaration attached to Greece's accession treaty to the Schengen Agreement states that Mount Athos's "special status" should be taken into account in the application of the Schengen rules.[27] The monks strongly objected to Greece joining the Schengen Area based on fears that the EU would be able to end the centuries-old prohibition on the admittance of women. The prohibition is unchanged and a special permit is required to enter the peninsula. The monks were also concerned that the agreement could affect their traditional right to offer sanctuary to people from Orthodox countries such as Russia.[28] Such monks do nowadays need a Greek visa and permission to stay, even if that is given generously by the Greek ministry, based on requests from Athos.[29]

Friends of Mount Athos[]

The Friends of Mount Athos (FoMA) is a society formed in 1990 by people who shared a common interest for the monasteries of Mount Athos, and a registered charity in the U.K. (Registered Charity No. 1047287). Timothy Ware, Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia, is the President of the society. Among its members are the late Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh and Charles, Prince of Wales, Heir Apparent to the British throne, who is the royal patron of the society.[30]

As a service to the monasteries and to pilgrims, the society clears and maintains the ancient footpaths of Mount Athos, with many of the stone-paved (Kalderimi) paths dating back to the Byzantine era. It also provides on its website detailed footpath descriptions with GPS tracks, and a regularly updated report on the condition of the paths. FoMA member and cartographer, Peter Howorth of Christchurch, New Zealand, working with the society's footpath team, has recently published a new Pilgrim Map.[31]

Among the society's publications are its annual bulletin (Friends of Mount Athos Annual Report) offering articles, book reviews and other features related to Mount Athos. Past issues are available from the society's web site. It also publishes A Pilgrim's Guide to Mount Athos in both printed and continuously updated digital forms.[31]

See also[]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ "Languages". Pilgrims Guide. Friends of Mount Athos (FoMA). Retrieved 2021-05-08.

- ^ "Η αλλαγή Ιεράς Επιστασίας στο Άγιο Όρος- Η Αγιορείτικη τελετή που έχει παλαιές ρίζες- Πλούσιο Φωτογραφικό υλικό". June 14, 2019.

- ^ "The new Civil Governor of Mount Athos at the Ecumenical Patriarch". September 5, 2019.

- ^ 2011 Greek census: "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός". Hellenic Statistical Authority. (in Greek)

- ^ Manson, Megan (11 Oct 2017). "UNESCO: Putting religious privilege above gender equality". secularism.co.uk. National Secular Society. Retrieved 11 Apr 2021.

- ^ Article 105 of the Constitution of Greece Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine – The regime of Mount Athos.

- ^ "MOUNT ATHOS: Failing Light". Time. 28 April 1941. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "The Hitler icon: How Mount Athos honored the Führer – Alan Nothnagle". Open Salon. 27 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Smith, Helena (11 August 2018). "Greece accuses Russia of bribery and meddling in its affairs". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (20 October 2018). "Mount Athos, a Male-Only Holy Retreat, Is Ruffled by Tourists and Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Joint Commission Of The Theological Dialogue Between The Orthodox Church And The Oriental Orthodox Churches. (1989). First Agreed Statement. Wadi-El-Natroun, Egypt: Anba Bishoy Monastery.

- ^ Joint Commission Of The Theological Dialogue Between The Orthodox Church And The Oriental Orthodox Churches. (1990). Second Agreed Statement. Chambesy, Geneva, Switzerland:Orthodox Center of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

- ^ Joint Commission Of The Theological Dialogue Between The Orthodox Church And The Oriental Orthodox Churches. (1993). Second Agreed Statement. Chambesy Geneva, Switzerland: Orthodox Center of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

- ^ Committee from the Sacred Community of the Holy Mountain Athos. (1994). Concerning the Dialogue of the Orthodox with the Non-Chalcedonians. Mount Athos, Greece: The Sacred Community of Mount Athos.

- ^ Robert Draper, "Mount Athos" Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, National Geographic magazine, December 2009

- ^ Graham Speake (2014). Mount Athos. Renewal in Paradise. Denise Harvey. ISBN 978-960-7120-34-2..

- ^ Variant names: Skiathis – Sketis – Skithis – Skitis – Skete – Oros Nitrias (Nitria) – Wadi el-Natrun – sites including Deir el-Surian (Deir el-Syriani), the monastery of Maria Deipara, Kellia, the monastery Deir Abu Maqar, Qaret el-Dahr, Quçur el-Rubaiyat according to the on-line dictionary "Trismegistos" <http://www.trismegistos.org/geo/detail.php?tm=3375 Archived 26 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ Mount Athos Archived 28 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, an IFPA (Independent Film Production Associates Limited) – Cinevideo co-production in association with Channel 4 Television, London. 1985.

- ^ Schwimmer, Walter. "Human Rights Aspects of Current Problems of Mount Athos". Report to international conference: "The Holy Mount Athos – the unique spiritual and cultural heritage of modern world" (Weimar, Germany) 23–26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ C 2006, ABC Design & Communication (12 November 1935). "VAGABOND – the first and only monthly magazine in English". Vagabond-bg.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Sack, John (1959). Report from Practically Nowhere. New York: Curtis Publishing Company. pp. 148–149.

- ^ The Climax of Sin Archived 14 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Time Magazine, 1953

- ^ "Women Invade Athos Despite 1,000-Year Ban". The New York Times. 26 April 1953. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ "European Parliament resolution on the situation concerning basic rights in the European Union". European Parliament. 15 January 2003. pp. Equality between men and women § 98. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ^ "Women breach all-male Greek site". BBC. 27 May 2008.

- ^ Why, Who, What (27 May 2016). "Why are women banned from Mount Athos?". BBC.

- ^ Joint Declaration No. 5 attached to the Final Act of the accession treaty.

- ^ "Monks see Schengen as Satan's work". BBC News. 16 June 1998.

- ^ Greece Archived 18 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Center for International Economic Cooperation)

- ^ "Prince visits 'monastic republic'". BBC. 12 May 2004.

- ^ a b "The Mount Athos Pilgrim Map". The Friends of Mount Athos. 2016. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Announcement of the Pilgrim Map, with link to the cartographer's website.

External links[]

- Subdivisions of Greece

- Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

- Theocracies

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Greece

- Mount Athos

- Men's religious organizations

- Autonomous regions

- Special territories of the European Union