Monkeys in Chinese culture

Monkeys, particularly macaques and monkey-like gibbons, have played significant roles in Chinese culture for over two thousand years. Some examples familiar to English speakers include the zodiacal Year of the Monkey, the Monkey King Sun Wukong in the novel Journey to the West, and Monkey Kung Fu.

Terminology[]

The Chinese language has numerous words meaning "simian; monkey; ape", some of which have diachronically changed meanings in reference to different simians. For instance, Chinese xingxing 猩猩 originally named "a mythical creature with a human face and pig body", and became the modern name for the "orangutan".

Within the classification of Chinese characters, almost all "monkey; ape" words – with the exceptions of nao 夒 and yu 禺 that were originally monkey pictographs – are written with radical-phonetic compound characters. These characters combine a radical or classifier that roughly indicates semantic field, usually the "dog/quadruped radical" 犭 for simians, and a phonetic element that suggests pronunciation. For instance, this animal classifier is a graphic component in hou 猴 (with a hou 侯 "marquis" phonetic) "macaque; monkey" and yuan 猿 (with yuan 袁 "long robe") "gibbon; monkey".

Note that the following discussion of "monkey; ape" terminology will cite three fundamental sources. The oldest extant Chinese dictionary, the (c. 3rd century BCE) Erya (Chapter 18, 釋獸 "Explaining Wild Animals") glosses seven names for monkeys and monkey-like creatures in the 寓屬 "Monkey/Wild Animal" taxonomy. The first Chinese character dictionary, the (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi defines many names of simians, primarily under the (犬部 "dog/quadruped" radical) in Chapter 11. The classic Chinese pharmacopoeia, Li Shizhen's (1597) Bencao Gangmu (獸之四 "Animals No. 4" chapter) lists medical uses for five Yu 寓 "monkeys" and three Kuai 怪 "supernatural beings". The latter are wangliang 魍魎 "a demon that eats the livers of corpses", penghou 彭侯 "a tree spirit that resembles a black tailless dog", and feng 封 "an edible monster that resembles a two-eyed lump of flesh".

Li Shizhen distinguishes 11 varieties of monkeys:

A small one with a short tail is called Hou ([猴] monkey). If it looks like a monkey but has a prominent moustache, then it is called Ju [狙]. If it looks like a monkey but is bigger, then it is Jue [貜]. A monkey that is big, with red eyes and a long tail, is called Yu [禺]. A monkey that is small but has a long tail and an upright nose is called You [狖]. A monkey that is similar to You but is bigger is called Guoran [果然]. A monkey that is similar to You but smaller is called Mengsong [蒙頌]. A monkey that is similar to You but jumps a lot is called Canhu [獑猢]. A monkey that has long arms is called Yuan ([猿] ape). A monkey that is similar to Yuan but has a golden tail is called Rong [狨]. A monkey that is similar to Yuan but bigger, and can eat apes and monkeys, is called Du [獨]. (s.v. Jue)[1]

Nao[]

Nao 夒 was the first "monkey" term recorded in the historical corpus of written Chinese, and frequently appeared in (14th–11th centuries BCE) Shang dynasty oracle bone inscriptions. This oracle pictograph of "a monkey" showed its head, arms, legs, and short tail; which were convergented as 目/頁 ("head"/"eye"), 又/爪 ("hand"/"claw") and later 止 ("foot", which was a corruption from 爪 in this character), 已/巳 ("finished"/"foetus", which was corrupt from the tail) not later than the end of (6th century BCE) Spring and Autumn Period bronze script. Compare the seal character for kui 夔 "a legendary demon with a human face and body of a monkey/dragon", which resembles the seal character for nao with the addition of what appears to be long hair on its head.

This graphically complex character nao 夒 "monkey" had an early variant nao 獿 (with the "quadruped" radical and nao phonetic), and a simpler replacement nao 猱 "monkey" (same radical and a rou 柔 phonetic), which is common in modern usage.

The etymology of nao < *nû 夒 or 猱 "monkey"[2] "is elusive", and may be connected with Proto-Mon–Khmer *knuuy "macaque; monkey" or Proto-Tibeto-Burman *mruk; compare *ŋoh 禺 next.

The first Chinese character dictionary, the (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi defines nao 夒 as "a greedy animal, generally said to be a muhou "monkey" resembling a person" (貪獸也一曰母猴似人); see muhou below.

The poet Li Bai alludes to nao (猱) populating the Taihang Mountains, in the north of China, near the capital city Chang'an, in the poem "白馬篇": it should be duly noted that this literary source contextually suggests a temporal location of the West Han era.[3]

Yu[]

Yu 禺 "monkey" appeared on (11th–3rd centuries BCE) Zhou dynasty Chinese ritual bronzes as a pictograph showing a head, arms, and a tail. Yu "forenoon, 9 to 11 AM" is the second of five daily divisions (更) in the traditional Chinese calendar. Banyu 番禺 was "a district in Guangzhou". In modern Chinese scientific usage, yu 禺 refers to the Central and South American "spider monkey".

The etymology of yu < *ŋoh 禺 "monkey"[4] links with Kukish *ŋa:w "ape" > Lushai ŋau "grey monkey"; compare *nû 夒 above.

The Shuowen Jiezi defines yu 禺 as "a kind of muhou "monkey" with a head resembling a gui "ghost"" (母猴屬頭似鬼). Compare the above definition of nao as a muhou "monkey" resembling a person.

Yu 禺 has a graphic variant yu 寓 (with the "roof radical") "reside; imply". The Erya (18) lists monkey definitions under a yushu 寓屬 "wild animal category". Guo Pu's commentary explains yu 寓 inclusively means all shou 獸 "wild animals", and van Gulik says it means "primates in general".[5]

The Shanhaijing uses yu 禺 to describe the xingxing, "There is an animal on the mountain which looks like a long-tailed ape, but it has white ears. It crouches as it moves along and it runs like a human. Its name is the live-lively. If you eat it, you'll be a good runner".[6]

The Shanhaijing records a mythical yugu 禺谷 "monkey valley", the place where the sun sets, which suggests that "the monkey is a kind of guardian of the approaches to the nether World".[5] Kuafu 禺谷 "Boast Father raced with the sun and ran with the setting sun", but died of thirst on the way.[7] Yugu is also written as yu 虞 "predict; deceive" or ou 偶 "human image; mate".

Hou and Muhou[]

Hou 猴 "monkey; macaque" is a common name for simians. For instance, houzi 猴子 means "monkey" or "clever/glib person". Muhou 母猴 "macaque; rhesus monkey" compounds mu "mother" and hou "monkey", and can also mean "female monkey" in modern usage. Van Gulik says that muhou is a phonetic rendering of a non-Chinese term" because mu- occurs in four variants: 母 and 沐 "wash one's hair" in Zhou texts, and 米 "rice" or 獼 in Han texts.[8] In modern Chinese usage, mihou 獼猴 means "macaque; rhesus monkey". The etymology of hou < Old Chinese *gô 猴 "monkey"[9] probably derives from Sino-Tibetan *ʔ-ko. The first syllable in muhou < *môʔ-gô 母猴 or muhou < *môk-gô 沐猴 "macaque" may perhaps be a "pre-initial" supported by the Lolo-Burmese mjo khœ < *mjok "monkey", which might have been the source of Proto-Tocharian *moko.

Lu Ji, who was from the southern state of Wu, noted muhou was a Chu word:[8] "The nao is the macaque [mihou], called by the people of Chu [muhou]. After a macaque has grown old, he becomes a que [貜]. Macaques with long arms are called gibbons (yuan). Gibbons with a white waist are called [chan 獑]." Van Gulik explains the legendary que with the grey whiskers of mature macaques, and associates the chan with the rhesus macaque, or huchan 胡獑, found in present day Yunnan.

The Lüshi Chunqiu mentions the muhou and notes its similarity to humans.[10]

The Shuowen jiezi defines hou as nao, and defines nao 夒, yu 禺, jue 玃, and wei 蜼 as muhou.

The Bencao gangmu lists mihou synonyms of: muhou 沐猴, weihou 為猴, husun 胡孫, wangsun 王孫, maliu 馬留, and ju 狙; and Li Shizhen explains the names.

The book Baihu Tongyi by Ban Gu: Hou means "wait" [hou 候, n.b., hou 猴 does not occur in the received text]. When it sees a man put some food in a trap, it will stay in a higher position and look at the food for a long time. It is an animal that is good at waiting. The macaque likes to wash its face by rubbing, so it is called Mu [沐 "washing"]. The character was later distorted to Mu ([母] meaning "mother"), which is even further from the original meaning. The book Shuowen Jiezi (Book of Philology by Xu Shen): The character Hou looks like Muhou (monkey), but it is not a female monkey. As macaque looks like a person from the Hu region (the north and west of China where non-Han ethnic groups lived in ancient times), it is called Husun [胡孫]. In the book Zhuang Zi, it is called Ju [狙]. People raise macaques in stables. In this way, horses will not be attacked by disease. So it is colloquially called Maliu ([馬留] meaning "maintaining the horses") in the Hu region (the north and west of China where non-Han ethnic groups lived in ancient times). In Sanskrit books it is called Mosizha [摩斯咤] (transliteration [of markaţa]).[11]

Bernard E. Read notes, "The menstrual discharge of the monkey [猴經] is said to give immunity to the horse against infectious disease", and suggests the Sanskrit name "is not so remote from the genus name Macacus".[12] Husun "macaque; monkey" is also written 猢猻, as punned in the surname of Sun Wukong 孫悟空 "descendent/monkey awakened to emptiness". Maliu 馬留 (lit. "horse keep") compares with the Cantonese maB2lɐuA1 "monkey" word.[13]

Yuan and naoyuan[]

Yuan 猿 "ape; monkey" is used in Chinese terms such as yuanren 猿人 "ape-man; Hominidae" and Beijing yuanren 北京猿人 "Peking Man".

The etymology of yuan < *wan 猿 "monkey"[14] could be linked with Proto-Tibeto-Burman *(b)woy or Proto-Mon–Khmer *swaaʔ "monkey".

Yuanhou 猿猴 "apes and monkeys", according to Van Gulik,[15] originally meant only "gibbons and macaques" but in the last few centuries, it has been widely used in Chinese literature as a comprehensive term for "monkeys". The Japanese language word enkō 猿猴 is likewise means "monkey" in general.

Naoyuan 猱蝯 compounds the nao 夒 variant 猱 with yuan 蝯 (combining the "insect radical" 虫 and yuan 爰 phonetic). Yuan has graphic variants of 猨 and 猿. The Erya defines "The naoyuan is good at climbing" (猱蝯善援), based upon a pun between yuan 蝯 "monkey" and yuan 援 "pull up; climb" (both characters written with the same phonetic element).

Nao 猱 occurs once in the Classic of Poetry, "Do not teach a monkey to climb trees" (毋教猱升木). Lu Ji's 3rd-century commentary says "The nao is the macaque [mihou], the people of Chu call it muhou (see above). In disagreement, Van Gulik gives reasons why nao 猱 means "gibbon" not "macaque".[16] First, the Erya stresses "climbing" as the simian's main characteristic. Second, Zhou dynasty texts record the nao as "a typical tree-ape". Third, numerous early literary sources use naoyuan or yuannao as a binomial compound.

Van Gulik distinguishes nao 猱 "gibbon" from the homonym nao 獶 "monkey" (with a you 憂 phonetic replacing the uncommon 夒 in nao 獿)

The term nao 獿 occurs in the Record of Music chapter of the Book of Rites criticizing vulgar pantomimes,[17] "Actors take part therein, and dwarfs who resemble nao, men and women mix, and the difference between parents and children is not observed"; "here nao clearly means a macaque, familiar through the popular monkey-shows."

Van Gulik suggests that Chinese yuan "gibbon" was a loanword from the language of Chu, the southernmost state of the Zhou realm.[15] Qu Yuan's (c. 3rd-century) Chuci uses the term yuanyou 猿狖 three times (in Nine Pieces); for instance,[18] "Amid the deep woods there, in the twilight gloom, are the haunts where monkeys live." This text also uses yuan 猿 once (Nine Songs), yuan 蝯 once (in Nine Laments), and houyuan 猴猿 once (in Nine Longings). If yuanyou was Qu Yuan's (or another Chuci author's) rendering of a Chu word for "gibbon", then naoyuan can be understood as a compound of the native Chinese word nao "monkey in general" and the sinified loanword yuan "gibbon"; and gradually, "nao 猱 came to mean "gibbon", whereas nao 獶 remained reserved for monkeys." You 狖 was a Zhou synonym for "gibbon".[19]

During the first centuries of our era, the binoms naoyuan or yuannao were superseded as words for "gibbon" by the single term yuan 猨, written with the classifier "quadruped" instead of that for "insect" 虫; and one prefers the phonetic 袁 to 爰 (rarely 員). This character yuan 猿 has remained the exclusive term for the Hylobatidae as long as the Chinese in general were familiar with the gibbon. However, when in the course of the centuries more and more mountainous regions were brought under cultivation, and as the deforestation increased accordingly, the habitat of the gibbon shrank to the less accessible mountain forests in the south and south-west, and the Chinese had few opportunities for seeing actual specimens. Until about the 14th century A.D. one may assume with confidence that when a Chinese writer employs the word yuan 猿, he means indeed a gibbon. Thereafter, however, the majority of Chinese writers knowing about the gibbon only by hearsay, they began to confuse him with the macaque or other Cynopithecoids – a confusion which has lasted till the present day.[15]

The Bencao gangmu[20] notes that, "the gibbon's meat may be taken as medicine against hemorrhoids, which may be cured also by always using a gibbon's skin as seat-cover. The fat used as ointment is said to be a wonderful cure for itching sores."

Rong[]

Rong 狨 was "a long-haired monkey with golden fur that was highly prized". Read[21] suggests it is the "lar gibbon, Hylobates entelloides", and Luo identifies it as the golden snub-nosed monkey Rhinopitheeus roxellana.[22] In addition to meaning "golden snub-nosed monkey", Van Gulik notes that in modern Chinese zoological terminology, rong denotes the Callitrichidae (or Hapalidae) family including marmosets and tamarins.[23]

The Bencao gangmu entry for the rong 狨 explains the synonym nao 猱 signifies this monkey's rou 柔 "soft; supple" hair.

The hair of the golden monkey is long and soft. So it is called Rong (meaning "fine hair"). Nao is a character meaning "soft." Another explanation says that the animal is found in the western Rong region [Sichuan], so it is thus named. There is a kind of long-hair dog that is also called Nao. ... The book Tan Yuan [談苑] by Yang Yi (楊億): The golden monkey is found in the deep mountains in Sichuan and Shaanxi. It looks like an ape. It has a long tail of golden color. So it is colloquially called Jinsirong [金絲狨] (meaning "golden thread monkey"). It is quick at climbing trees. It loves its tail dearly. When shot by a poisonous arrow, it will bite off its own tail when poisoned. During the Song dynasty (960–1279), only officials of the administration and military of the third rank and above were allowed to use seats and bedding made of golden monkey hide.[24]

This entry has two subheadings: the yuan 猨 or changbeihou 長臂猴 "gibbon, Hylobates agilis" and the du 獨 (below).

The ape is good at climbing trees. It is found in the deep mountains in the Chuan and Guang regions. It looks like a monkey, but has very long arms. It is an animal that can practice [Daoist] qi (Vital Energy), so it lives a long life. Some say it has one arm stretching from one side to the other. This is not correct. Its arm bone can be made into a flute that sounds very clear and resonant. Apes come in different colors: blue-green, white, black, yellow and crimson. It is a kind and quiet animal, and likes to eat fruits. It lives in forests and can jump over a distance of several dozen chi. But when it falls and drops onto the ground, it may suffer from excessive diarrhea and then die. Treatment is the drinking of juice of Fuzi/radix aconiti lateralis/daughter root of common monkshood. Apes live in groups. The male cries a lot. It makes three cries consecutively. The cry sounds miserable and is penetrating. The book Guihai Zhi [桂海志] by Fan Chengda: There are three varieties of apes: Yellow ones with golden thread; black ones with jade faces; and black ones with black faces. Some say the pure black one is the male, and the golden thread one is the female. A male one shouts and a female does not. The book Rixun Ji [日詢記] by Wang Ji: People in the Guang region say that when an ape is born, it is black and male, When it gets old, it turns yellow and its genitals become ulcerous, and then it turns into a female. Then it mates with the black one. After another several hundred years, the yellow ape will evolve into a white one.[25]

Jue and Juefu[]

Juefu 貜父 "a large monkey" compounds jue "an ape" and fu "father". The character jue 貜 combines the "cat/beast radical" 豸 and a jue 矍 "look startled" phonetic (with two 目 "eyes"); compare the graphic variants of 玃 and 蠼. Based upon this phonetic element, the Erya[26] glosses: "Juefu, good at looking." (貜父善顧). The juefu is also called jueyuan 玃猿, which is known as Kakuen in Japanese mythology.

The fulu 附錄 "appendix" to the Bencao gangmu entry for mihou "macaque" adds the jue 玃 "A species of large ape or hoolock, found in Western China, and said to be six feet high, it probably denotes the great gibbon, Hylobates", the "northern gray gibbon, Hylobates muelleri funereus" (viz., Müller's Bornean gibbon);[27] and the ju 豦 (graphically "tiger" and "pig") "wild boar; a yellow and black monkey" or jufu 舉父 "lift/raise father", the "lion-tailed macaque, Macaca/Inuus silenus".[28] The jue entry says:

It is a kind of old monkey. It lives in the mountains in western Sichuan. It looks like a monkey. But it is bigger and is gray and black. It can walk like a human. It robs things from humans, and looks around its surrounding from time to time. There are only male ones and no female ones, so it is also called Juefu (father monkey) or Jiajue. It may kidnap a girl and marry her to have children. The book Shenyi Jing: There is a kind of animal called Zhou in the west that is as big as a donkey but looks like a monkey. It can climb trees. There are only female ones and no males. They block the road in the mountains and kidnap men who happen to pass on the road. The men are then forced to mate with then. This is the way the animal gets offspring. It is also a kind of Jue, but a female one.[29]

This all-female zhou monkey is written with a non-Unicode character, combining the 豸 radical and zhou 周 phonetic.

Li Shizhen describes the ju(fu):

It is found in the mountains in Jianping. It is the size of a dog but looks like a monkey. It is black and yellow, and covered with a big beard and bristles. It may throw stones to strike humans. The book Xishan Jing: There is a kind of animal in Chongwu Mountain. It looks like Yu but has long arms. It is good at throwing stones. It is called Jufu.[30]

Ju[]

Ju 狙 originally meant "macaque; monkey" and came to mean "spy; watch for" (e.g., juji 狙擊 "attack from ambush). The Shuowen jiezi defines ju as "a kind of [jue] monkey, also said to mean a dog that briefly bites a person" (玃屬一曰狙犬也暫齧人者).

The (c. 4th–3rd centuries BCE) Zhuangzi was the oldest Chinese classic to use ju. For instance, it has two versions of a quote from Laozi (called Lao Dan 老聃, lit. "old helixless-ears") using the term yuanzu 猿狙 "gibbon and macaque; monkey" to exemplify someone who is not a Daoist sage.

"Compared to the sages," said Old Longears "he would be like a clerk at his labors or a craftsman tied to his work, toiling his body and vexing his mind. Furthermore, it is the patterned pelt of the tiger and the leopard that bring forth the hunter, it is the nimbleness of the gibbon and the monkey that bring forth the trainer with his leash. Can such as these be compared with enlightened kings?" (7)[31]

The Shanhaijing mentions two mythological animals named with ju. First, the xieju 猲狙 (with xie or he "short-muzzled dog"):

There is an animal on this mountain which looks like a wolf, but it has a scarlet head and rat eyes. It makes a noise like a piglet. Its name is the snubnose-dogwolf. It eats humans. (4)[32]

Second, the zhuru 狙如 (with ru "be like"):

There is an animal on this mountain which looks like a white-eared rat; it has white ears and white jaws. Its name is the monkey-like. Whenever it appears, that kingdom will have a great war. (5)[33]

Xingxing[]

Xingxing 猩猩 or shengsheng 狌狌"a monkey; orangutan" reduplicates xing, which graphically combines the "quadruped radical" with a xing 星 "star" phonetic, or with sheng 生 "life" in the variant xing or sheng 狌. The name is used for foreign simians in modern terminology, xingxing means "orangutan", heixingxing with hei- 黑 "black" means "chimpanzee", and daxingxing with da- 黑 "large" means "gorilla".

The Erya says, "The [xingxing] is small, and likes to cry." (猩猩小而好啼). Guo Pu's commentary notes,[34] "The Shanhaijing says: It has a human face and the body of a pig, and it is able to speak. At present it is found in [Jiaoji] and the [Fengxi] district (i.e. North Indo-China). The [xingxing] resembles a [huan 獾] (badger) or small pig. Its call resembles the crying of a small child." Fengxi 封谿 corresponds to modern Bắc Ninh Province in Vietnam.

The Huainanzi says, "The orangutan knows the past but does not know the future; the male goose knows the future but does not know the past."; Gao You's commentary says,[35] "The [xingxing] has a human face but the body of a beast, and its colour is yellow. It is fond of wine."[36]

The Bencao gangmu entry for the xingxing or shengsheng, which Read[37] identifies as the "orangutan, Simia satyrus", records,

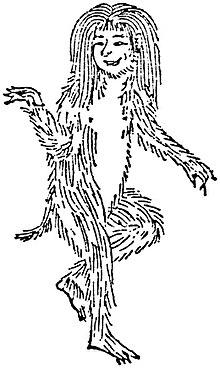

Li Shizhen: An orangutan can talk and knows about the future. Xingxing [猩猩] means [xingxing 惺惺] "intelligent". The orangutan was recorded in books like Er Ya and Yi Zhou Shu several dozen times. The following explanation is a summary: It is found in the mountain valleys in the Ailaoyi area and Fengxi County in Jiaozhi. It looks like a dog or a macaque. Its yellow hair resembles that of an ape, and its white ears resemble those of a pig. Its face looks human, and its legs are similar to those of a man. It has long hair and a good-looking face and head. It cries in the same way as a baby cries, or as a dog barks. They flock together and move covertly. Ruan Qian: Local people in Fengxi catch the animal in the following way: They place some wine and straw sandals on the roadside. Orangutans will come to the spot and call out the names of the ancestors of the people who placed the things. Then they leave temporarily and come back shortly afterwards. They drink the wine and try the sandals on. While the orangutans are enjoying themselves, people catch them and then keep them in cages. When one of them is to be killed, the fattest one will be chosen. It weeps sadly. People in the Xihu area use its blood to dye a kind of woolen fabric, which will maintain its bright color for a long time. After a puncture is made in the orangutan to let out blood, the person will flog the animal and ask it for the number of beatings. The flogging will stop after one dou of blood has been collected. The book Li Ji (Record of Rites) said that the orangutan could speak. The book Guang Zhi by Guo Yigong said that the orangutan could not speak. The book Shanhai Jing also said that the orangutan could speak. [Li Shizhen comments]: The orangutan is a kind of animal that looks like a human being. It looks like an ape or a monkey and can speak simple words like a parrot. It may not be the same as what Ruan Qian said. The book Er Ya Yi by Luo Yuan: In ancient books, the orangutan was described as similar to a pig, dog or monkey. But now it is recorded that the animal looks like a baboon. It looks like a naked bare-foot woman with long hair hanging from the head. They do not seem to have knees, and they travel in a group. When they encounter human beings, they cover their bodies with their hands. People say this is a kind of savage human. According to what Luo Yuan said, it seems such a creature is actually a Yenü (meaning "wild girl") or Yepo (meaning "wild woman"). Are they the same?[38]

The subentry for the yenü 野女 "wild women" or 野婆 "wild wife" says,

The book Bowu Zhi [博物志] by Tang Meng: In the Rinan area there is a kind of creature called the Yenü (meaning "wild girl") that travels in group. No male ones are to be found. They are white and crystal-like, wearing no clothes. The book Qidong Yeyu by Zhou Mi [周密]: Yepo (meaning "wild woman") is found in Nandanzhou. It has yellow hair shaped into coils. It is naked and wears no shoes. It looks like a very old woman. All of them are female and there are no male ones. They climb up and down the mountain as fast as golden monkeys. Under their waists are pieces of leather covering their bodies. When they encounter a man, they will carry him away and force him to mate. It is reported once that such a creature was killed by a strong man. It protected its waist even when it was being killed. After dissecting the animal, a piece of seal chip was found that was similar to a piece of gray jade with inscriptions on it. Li Shizhen: According to what Ruan Qian and Luo Yuan said above, it seems that this Yenü is actually an orangutan. As to the seal chip found in the animal, it is similar to the case that the testes of a male mouse are said to have seal characters [fuzhuan 符篆 "symbolic seal script"] on them, and the case that under the wing of a bird a seal of mirror has been found. Such things are still unclear to us.[39]

The bright scarlet dye known as xingxingxue 猩猩血 "gibbon's blood" was not used by the Chinese, but observed in imported Western textiles. Although the source for this tradition of the bloody dye remains untraced, Edward H. Schafer notes a Western analogue in "St. John's blood", a variety of the red dye kermes, which derives from the insect kermes.[40] The Tang dynasty chancellor Pei Yan wrote,

The hu ["barbarians"] of the Western countries take its blood for dyeing their woolen rugs; its color is clean and will not turn black. Some say that when you prick it for its blood, if you ask, "How much will you give me?" the [xingxing] will say, "Would two pints be truly enough?" In order to add to this amount, you thrash it with a whip before asking and it will go along with an increase, so that you can obtain up to a gallon. (Quan Tangwen 全唐文).[41]

Edward H. Schafer quotes a Tang story.

A number of the beasts were captured and put in a pen, to be cooked for the magistrate of a Tonkinese town. They picked the fattest of their number and thrust it weeping forth, to await the magistrate's pleasure in a covered cage: "The Commandant asked what thing this was, and the [xingxing] spoke from within the cage, and said, 'Only your servant and a jug of wine!' The Commandant laughed, and cherished it." Of course the clever, winebibbing animal became a treasured pet.[42]

The Chinese belief that gibbons enjoyed drinking wine has parallels in Classical antiquity, "monkeys were reputed to be overfond of wine, as Aristotle, Aelian, and Pliny observed, and their drunkenness made them easy to capture." Chinese stories about the xingxing liking wine appealed to the Japanese. In Japanese mythology, the Shōjō 猩猩 was a god of wine with a red face and long, red hair, who was always drunk and dancing merrily. Compare the drunken monkey hypothesis that the human attraction to ethanol may have a genetic basis.

Feifei[]

Feifei 狒狒 "monkey; baboon" reduplicates fei, written with the "dog/quadruped radical" 犭with a fu 弗 phonetic. Van Gulik says Chinese zoologists have adopted feifei as a convenient modern rendering of "baboon".[43]

The Erya glosses, "The feifei resembles a person; it has long hair hanging down on its back; it runs quickly and devours people." (狒狒如人被髮迅走食人). Guo Pu's commentary says,

This is the [xiaoyang 梟羊] "owl-goat". The [Shanhaijing] says: As to its shape it has a human face, with long lips; its body is black, with hair hanging down to its heels. When meeting with people it laughs. This animal occurs in N[orth] Indo-China, [Guangxi], and [Guangdong]. The large ones are over ten feet tall. Locally the animal is called [shandu 山都].[44]

Xiaoyang 梟羊 is a variant of the mythic xiaoyang 梟楊 "owl-poplar", which David Hawkes describes as "an anthropoid monster whose upper lip covers his face when he laughs. His laughter was sinister, it was said, being an indication that he was about to eat human flesh."[45]

The Shuowen Jiezi writes feifei