Shuowen Jiezi

| Shuowen Jiezi | |||

|---|---|---|---|

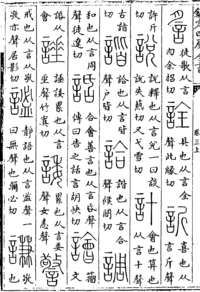

Cover of a modern reprint of a Song dynasty "veritable" edition (真本) of the Shuowen Jiezi | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 說文解字 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 说文解字 | ||

| Literal meaning | "Explaining Graphs and Analyzing Characters" | ||

| |||

Shuowen Jiezi (Chinese: 說文解字; lit. 'discussing writing and explaining characters') is an ancient Chinese dictionary from the Han dynasty. Although not the first comprehensive Chinese character dictionary (the Erya predates it), it was the first to analyze the structure of the characters and to give the rationale behind them, as well as the first to use the principle of organization by sections with shared components called radicals (bùshǒu 部首, lit. "section headers").

Circumstances of compilation[]

Xu Shen, a Han Dynasty scholar of the Five Classics, compiled the Shuowen Jiezi. He finished editing it in 100 CE, but due to an unfavorable imperial attitude towards scholarship, he waited until 121 CE before having his son Xǔ Chōng present it to Emperor An of Han along with a memorial.

In analyzing the structure of characters and defining the words represented by them, Xu Shen strove to disambiguate the meaning of the pre-Han Classics, so as to render their usage by government unquestioned and bring about order, and in the process also deeply imbued his organization and analyses with his philosophy on characters and the universe. According to Boltz (1993:430), Xu's compilation of the Shuowen "cannot be held to have arisen from a purely linguistic or lexicographical drive." His motives were more pragmatic and political. During the Han era, the prevalent theory of language was Confucianist Rectification of Names, the belief that using the correct names for things was essential for proper government. Xu's postface (xù 敘) to the Shuowen Jiezi (tr. O'Neill 2013: 436) explains: "Now, as for writing systems and their offspring characters, these are the root of the classics, the origin of kingly government, what former men used to hand down to posterity, and what later men use to remember antiquity." Compare how the postface describes the legendary invention of writing for governmental rather than for communicative purposes:

The Scribe of the Yellow Emperor, Cangjie, observing the traces of the footprints and tracks of birds and wild animals, understood that their linear structures could be distinguished from one another by the differences between them. When he first created writing by carving in wood, the hundred officials became regulated, and the myriad things became discriminated. (tr. O'Neill 2013: 430)

Pre-Shuowen Chinese dictionaries like the Erya and the Fangyan were limited lists of synonyms loosely organized by semantic categories, which made it difficult to look up characters. Xu Shen analytically organized characters in the comprehensive Shuowen Jiezi through their shared graphic components, which Boltz (1993:431) calls "a major conceptual innovation in the understanding of the Chinese writing system."

Structure[]

Xu wrote the Shuowen Jiezi to analyze seal script (specifically xiǎozhuàn 小篆 "small seal") characters that evolved slowly and organically throughout the mid-to-late Zhou dynasty in the state of Qin, and which were then standardized during the Qin dynasty and promulgated empire-wide. Thus, Needham et al. (1986: 217) describe the Shuowen jiezi as "a paleographic handbook as well as a dictionary".

The dictionary includes a preface and 15 chapters. The first 14 chapters are character entries; the 15th and final chapter is divided into two parts: a postface and an index of section headers. Xǔ Shèn states in his postface that the dictionary has 9,353 character entries, plus 1,163 graphic variants, with a total length of 133,441 characters. The transmitted texts vary slightly in content, owing to omissions and emendations by commentators (especially Xú Xuàn, see below), and modern editions have 9,831 characters and 1,279 variants.

Sections[]

Xu Shen categorized Chinese characters into 540 sections, under "section headers" (bùshǒu, now the standard linguistic and lexicographical term for character radicals): these may be entire characters or simplifications thereof, which also serve as components shared by all the characters in that section. The number of section headers, 540, numerologically equals 6 × 9 × 10, the product of the symbolic numbers of Yin and Yang and the number of the Heavenly Stems.[citation needed] The first section header was 一 (yī "one; first") and the last was 亥 (hài, the last character of the Earthly Branches).

Xu's choice of sections appears in large part to have been driven by the desire to create an unbroken, systematic sequence among the headers themselves, such that each had a natural, intuitive relationship (e.g., structural, semantic or phonetic) with the ones before and after, as well as by the desire to reflect cosmology. In the process, he included many section headers that are not considered ones today, such as 炎 (yán "flame") and 熊 (xióng "bear"), which modern dictionaries list under the 火 or 灬 (huǒ "fire") heading. He also included as section headers all the sexagenary cycle characters, that is, the ten Heavenly Stems and twelve Earthly Branches. As a result, unlike modern dictionaries which attempt to maximize the number of characters under each section header, 34 Shuowen headers have no characters under them, while 159 have only one each. From a modern lexicographical perspective, Xu's system of 540 headings can seem "enigmatic" and "illogical".[1] For instance, he included the singular section header 409 惢 (ruǐ "doubt"), with only one rare character (ruǐ 繠 "stamen"), instead of listing it under the common header 408 心 (xīn "heart; mind").

Character entries[]

The typical Shuowen format for a character entry consists of a seal graph, a short definition (usually a single synonym, occasionally in a punning way as in the Shiming), a pronunciation given by citing a homophone, and analysis of compound graphs into semantic and/or phonetic components. Individual entries can additionally include graphic variants, secondary definitions, information on regional usages, citations from pre-Han texts, and further phonetic information, typically in dúruò (讀若 "read like") notation.[3] In addition to the seal graph, Xu included two kinds of variant graphs when they differed from the standard seal, called ancient script (gǔwén 古文) and Zhòu script (Zhòuwén 籀文, not to be confused with the Zhou dynasty).

The Zhòu characters were taken from the no-longer extant Shizhoupian, an early copybook traditionally attributed to a Shĭ Zhòu, or Historian Zhou, in the court of King Xuan of Zhou (r. 827–782 BCE). Wang Guowei and Tang Lan argued that the structure and style of these characters suggested a later date, but some modern scholars such as Qiu Xigui argue for the original dating.[4]

The guwen characters were based on the characters used in pre-Qin copies of the classics recovered from the walls of houses where they had been hidden to escape the burning of books ordered by Qin Shihuang. Xu believed that these were the most ancient characters available, since Confucius would have used the oldest characters to best convey the meaning of the texts. However, Wang Guowei and other scholars have shown that they were regional variant forms in the eastern areas during the Warring States period, from only slightly earlier than the Qin seal script.[5]

Even as copyists transcribed the main text of the book in clerical script in the late Han, and then in modern standard script in the centuries to follow, the small seal characters continued to be copied in their own (seal) script to preserve their structure, as were the guwen and Zhouwen characters.

Character analysis[]

The title of the work draws a basic distinction between two types of characters, wén 文 and zì 字, the former being those composed of a single graphic element (such as shān 山 "mountain"), and the latter being those containing more than one such element (such as hǎo 好 "good" with 女 "woman" and 子 "child") which can be deconstructed into and analyzed in terms of their component elements. Note that the character 文 itself exemplifies the category wén 文, while 字 (which is composed of 宀 and 子) exemplifies zì 字. Thus, Shuōwén Jiězì means "commenting on" (shuō "speak; talk; comment; explain") the wén, which cannot be deconstructed, and "analyzing" (jiě "untie; separate; divide; analyze; explain; deconstruct") the zì.[6]

Although the "six principles" of Chinese character classification (liùshū 六書 "six graphs") had been mentioned by earlier authors, Xu Shen's postface was the first work to provide definitions and examples. He uses the first two terms, simple indicatives (zhǐshì 指事) and pictograms (xiàngxíng 象形) to explicitly label character entries in the dictionary, e.g., in the typical pattern of "(character) (definition) ...simple indicative" (A B 也...指事 (也)).[7] Logographs belonging to the third principle, phono-semantic compound characters (xíngshēng 形聲), are implicitly identified through the entry pattern A… from B, phonetically resembles C (A...從 B, C 聲), meaning that element B plays a semantic role in A, while C gives the sound.[8] The fourth type, compound indicatives (huìyì 會意), are sometimes identified by the pattern A...from X from Y (A...從 X 從 Y), meaning that the compound A is given meaning through the graphic combination and interaction of both constituent elements. The last two of the six principles, borrowed characters (aka phonetic loan, jiǎjiè 假借) and derived characters (zhuǎnzhù 轉注), are not identifiable in the character definitions.[9]

According to Imre Galambos, the function of the Shuowen was educational. Since Han studies of writing are attested to have begun by pupils of 8 years old, Xu Shen's categorization of characters was proposed to be understood as a mnemonic methodology for juvenile students.[10]

Textual history and scholarship[]

Although the original Han dynasty Shuōwén Jiězì text has been lost, it was transmitted through handwritten copies for centuries. The oldest extant trace of it is a six-page manuscript fragment from the Tang dynasty, amounting to about 2% of the entire text. The fragment, now in Japan, concerns the mù (木) section header. The earliest post-Han scholar known to have researched and emended this dictionary, albeit badly, was Lǐ Yángbīng (李陽冰, fl. 765–780), who "is usually regarded as something of a bête noire of [Shuowen] studies," writes Boltz, "owing to his idiosyncratic and somewhat capricious editing of the text."[11]

Shuowen scholarship improved greatly during the Southern Tang-Song dynasties and later during the Qing dynasty. The most important Northern Song scholars were the Xú brothers, Xú Xuàn (徐鉉, 916–991) and Xú Kǎi (徐鍇, 920–974). In 986, Emperor Taizong of Song ordered Xú Xuàn and other editors to publish an authoritative edition of the dictionary. This was published as the 説文解字繫傳 Shuowen Jiezi xichuan.

Xu Xuan's textual criticism has been especially vital for all subsequent scholarship, since his restoration of the damage done by Lǐ Yángbīng resulted in the closest version we have to the original, and the basis for all later editions. Xu Kai, in turn, focused on exegetical study, analyzing the meaning of Xu Shen's text, appending supplemental characters, and adding fǎnqiè pronunciation glosses for each entry. Among Qing Shuowen scholars, some like Zhū Jùnshēng (朱駿聲, 1788–1858), followed the textual criticism model of Xu Xuan, while others like Guì Fù (桂馥, 1736–1805) and Wáng Yún (王筠, 1784–1834) followed the analytical exegesis model of Xu Kai. One Qing scholar, Duan Yucai, stands above all the others due to the quality of his research in both areas. His annotated Shuowen edition (Shuowen Jiezi Zhu) is the one most commonly used by students today.

Although the Shuowen Jiezi has had incalculable value to scholars and was traditionally relied upon as the most important early source on the structure of Chinese characters, many of its analyses and definitions have been eclipsed as vague or inaccurate since the discovery of oracle bone inscriptions in the late 19th century.[citation needed] It therefore can no longer be relied upon as the single, authoritative source for definitions and graphic derivations. Xu Shen lacked access to oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang dynasty and bronzeware inscriptions from the Shang and Western Zhou dynasty, to which scholars now have access; they are often critical for understanding the structures and origins of logographs. For instance, he put lǜ (慮 "be concerned; consider") under the section heading 思 (sī "think") and noted it had a phonetic of hǔ (虍 "tiger"). However, the early bronze graphs for lǜ (慮) have the xīn (心 "heart") semantic component and a lǚ (呂 "a musical pitch") phonetic, also seen in early forms of lǔ (盧 "vessel; hut") and lǔ (虜 "captive").

Scholarship in the 20th century offered new understandings and accessibility. Ding Fubao collected all available Shuowen materials, clipped and arranged them in the original dictionary order, and photolithographically printed a colossal edition. Notable advances in Shuowen research have been made by Chinese and Western scholars like Mǎ Zōnghuò (馬宗霍), Mǎ Xùlún (馬敘倫), William G. Boltz, Weldon South Coblin, Thomas B.I. Creamer, Paul Serruys, Roy A. Miller, and K.L. Thern.

See also[]

- List of Kangxi radicals – a later way to classify Chinese characters

- Shuowen Jiezi (television program)

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Thern 1966, p. 4.

- ^ Qiu 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Coblin 1978.

- ^ Qiu 2000, pp. 72–77.

- ^ Qiu 2000, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Boltz 1993, p. 431.

- ^ Boltz 1993, p. 432.

- ^ Boltz 1993, pp. 432–433.

- ^ Boltz 1993, p. 433.

- ^ Galambos 2006, pp. 54–61.

- ^ Boltz 1993, p. 435.

Sources[]

- Atsuji Tetsuji (阿辻哲次). Kanjigaku: Setsumon kaiji no sekai 漢字学―説文解字の世界. Tôkyô: Tôkai daigaku shuppankai, 1985. ISBN 4-486-00841-3, ISBN 978-4-486-00841-5

- Boltz, William G. (1993), "Shuo wen chieh tzu 說文解字", in Loewe, Michael (ed.), Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide, Early China Special Monograph Series, 2, Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China, and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, pp. 429–442, ISBN 978-1-55729-043-4.

- Bottéro Françoise. (1996). «Sémantisme et classification dans l'écriture chinoise : Les systèmes de classement des caractères par clés du Shuowen Jiezi au Kangxi Zidian. Collège de France-IHEC. (Mémoires de l'Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises; 37). ISBN 2-85757-055-4

- Bottéro, Françoise; Harbsmeier, Christoph (2008), "The Shuowen Jiezi dictionary and the human sciences in China" (PDF), Asia Major, 21 (1): 249–271.

- Chén, Zhāoróng 陳昭容 (2003), 秦��文字研究:从漢字史的角度考察 [Research on the Qin Lineage of Writing: An Examination from the Perspective of the History of Chinese Writing], 中央研究院歷史語言研究所專刊 Academia Sinica Institute of History and Philology Monograph (in Chinese), ISBN 957-671-995-X.

- Coblin, W. South. (1978), "The initials of Xu Shen's language as reflected in the Shuowen duruo glosses", Journal of Chinese Linguistics (6): 27–75.

- Creamer, Thomas B.I. (1989) "Shuowen Jiezi and Textual Criticism in China," International Journal of Lexicography 2:3, pp. 176–187.

- Ding Fubao (丁福保). 1932. Shuowen Jiezi Gulin (說文解字詁林 "A Forest of Glosses on the Shuowen Jiezi"). 16 vols. Repr. Taipei: Commercial Press. 1959. 12 vols.

- Duan Yucai (1815). "說文解字注" (Shuōwén Jĭezì Zhù, commentary on the Shuōwén Jíezì), compiled 1776–1807. This classic edition of Shuowen is still reproduced in facsimile by various publishers, e.g., in Taipei by Li-ming Wen-hua Co Tiangong Books (1980, 1998), which edition conveniently highlights the main entry seal characters in red ink, and adds the modern kǎi 楷 standard script versions of them at the tops of the columns, with bopomofo phoneticization alongside.

- Galambos, Imre (2006), Orthography of early Chinese writing: evidence from newly excavated manuscripts, Budapest monographs in East Asian Studies, 1, Department of East Asian Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, ISBN 978-963-463-811-7.

- Qiu, Xigui (2000), Chinese writing, translated by Gilbert L. Mattos; Jerry Norman, Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China and The Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, ISBN 978-1-55729-071-7. (English translation of Wénzìxué Gàiyào 文字學概要, Shangwu, 1988.)

- Needham, Joseph, Lu Gwei-djen, and Huang Hsing-Tsung (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1 Botany. Cambridge University Press.

- O'Neill, Timothy (2013), "Xu Shen's Scholarly Agenda: A New Interpretation of the Postface of the Shuowen jiezi," Journal of the American Oriental Society 133.3: 413-440.

- Serruys, Paul L-M. (1984) "On the System of the Pu Shou 部首 in the Shuo-wen chieh-tzu 說文解字", Zhōngyāng Yánjiūyuàn Lìshǐ Yǔyán Yánjiùsuǒ Jíkān (中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊, Journal of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica), v.55:4, pp. 651–754.

- (in Chinese) Wang Guowei (1979). "史籀篇敘錄" [Commentary on the Shĭ Zhoù Piān] and "史籀篇疏證序" [Preface to a Study of the Shĭ Zhòu Piān], in 海寧王靜安先生遺書‧觀堂集林 [The Collected works of Mr. Wáng Jìng-Ān of Hǎiníng (Guan Tang Ji Lin)]. Taipei: 商務印書館 Commercial Press reprint, pp. 239–295.

- (in Chinese) Xu Zhongshu zh:徐中舒. "丁山說文闕義箋" [Commentary on the errors in Shuowen by Ding Shan]

External links[]

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Explicatives

- Cook, Richard (2001), The Extreme of Typographic Complexity: Character Set Issues Relating to Computerization of The Eastern Han Chinese Lexicon Shuowenjiezi (PDF), STEDT Project, Linguistic Department, University of California, Berkeley

- pages 28–29 : List of the 540 radicals in Xiaozhuan.

- Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 – Chinaknowledge (Archive)

- (in Japanese) 「説文解字」の540部首系統図 – がらんどう文字講座, Shuōwén Jiězì radical chart (Archive)

- Copies

- (in Chinese) 《說文解字》, comparative database of different editions – Beijing Normal University

- (in Chinese) 《說文解字》, electronic edition – Chinese Text Project

- (in Chinese) 《说文解字注》 全文检索 – 许慎撰 段玉裁注, facsimile edition

- Scanned editions at the Internet Archive:

- Various

- (in Chinese) 《說文解字》全文檢索測試版

- (in Chinese) 《說文解字》在线查询

- Chinese Etymology, online dictionary with Shuowen's definitions – Richard Sears

- (in Japanese and English) – 漢字データベースプロジェクト/Kanji Database Project

- Shuowen online text version with Duàn Yùcái "說文解字注", 釋名 Shiming, 爾雅 Erya, 方言 Fangyan, 廣韻 Guangyun définitions and glosses by Alain Lucas & Jean-Louis Schott and with "集韻 Jiyun" and "玉篇 Yupian" texts by Jean-Louis Schott.

- Han dynasty texts

- Chinese classic texts

- Chinese dictionaries

- Chinese characters

- History of linguistics

- 2nd-century books