Montenegrin–Ottoman War (1876–1878)

| Montenegrin–Ottoman War of 1876–1878 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Great Eastern Crisis | |||||||||

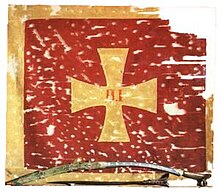

Montenegrin krstaš-barjak from the Battle of Vučji Do, damaged by bullets from the Ottoman forces, one of the symbols of the war and Montenegrin resistance. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Prince Nicholas I Marko Miljanov Popović Simo Baćović |

Ahmed Muhtar Pasha Osman Pasha | ||||||||

The Montenegrin–Ottoman War (Serbian Cyrillic: Црногорско-турски рат, romanized: Crnogorsko-turski rat, "Montenegrin-Turkish War"), also known in Montenegro as the Great War (Вељи рат, Velji rat), was fought between the Principality of Montenegro and the Ottoman Empire between 1876 and 1878. The war ended with Montenegrin victory. Six major and 27 smaller battles were fought, among which was the crucial Battle of Vučji Do.

A rebellion in nearby Herzegovina sparked a series of rebellions and uprisings against the Ottomans in Europe. Montenegro and Serbia agreed to declare a war on the Ottomans on 18 June 1876. The Montenegrins allied themselves with Herzegovians. One battle that was crucial to Montenegro's victory in the war was the Battle of Vučji Do. In 1877, Montenegrins fought heavy battles along the borders of Herzegovina and Albania. Prince Nicholas took the initiative and counterattacked the Ottoman forces that were coming from the north, south and west. He conquered Nikšić (24 September 1877), Bar (10 January 1878), Ulcinj (20 January 1878), Grmožur (26 January 1878) and Vranjina and Lesendro (30 January 1878).

The war ended when the Ottomans signed a truce with the Montenegrins at Edirne on 13 January 1878. The advancement of Russian forces toward the Ottomans forced the Ottomans to sign a peace treaty on 3 March 1878, recognising the independence of Montenegro, as well as Romania and Serbia, and also increased Montenegro's territory from 4,405 km² to 9,475 km². Montenegro also gained the towns of Nikšić, Kolašin, Spuž, Podgorica, Žabljak, Bar, as well as access to the sea.

Background[]

In October 1874, an influential Ottoman statesman, Jusuf-beg Mučin Krnjić, was murdered in Podgorica, which at the time was an Ottoman town near the border with Montenegro. It is believed that he had been killed by a close relative of vojvoda Marko Miljanov, a Montenegrin general who also, most likely, instigated the assassination. As a consequence, the Ottomans launched an action of retaliation against the local population and Montenegrin citizens present at the farmers' market in Podgorica, modern-day capital of Montenegro. It is estimated that 17 unarmed Montenegrins had been killed. This event is known as the "Podgorica's slaughter" (Podgorički pokolj). It resulted in bad relations between Montenegro and the Ottoman Empire, which further deteriorated with the outbreak of the uprising in Herzegovina (1875). Montenegro conducted the uprising, providing the rebels with military and financial aid and representing their interests to the Porte. Montenegro requested that part of Herzegovina be handed over to the Montenegrins, but the Porte declined. Because of this, Montenegro declared war on 18 June 1876, immediately followed by its foremost ally, the Principality of Serbia.

War[]

In the beginning of the war, when Miljanov arrived at Kuči, at the Ottoman frontier, the Kuči revolted and attacked the Ottomans.[1] The Pasha filled Medun and other small forts, Fundina, Koći, Zatrijebač and Orahovo with soldiers.[1]

The Piperi and Kuči tribes together attacked Koći, killing a small part, while they found Ottomans in tower houses whom they wanted to destroy with wooden cannons.[2] An epic poem about the war tells how Abdi Pasha the Cherkessian with 20,000 soldiers of the sanjak of Scutari was sent by the sultan to attack the Kuči and Piperi.[3] The poem tells how part of the army advanced on Koći and then fought in Zatrijebač and Fundina.[3]

In the Montenegrin-Ottoman war, the Montenegrin army managed to capture certain areas and settlements along the border, while encountering strong resistance from Albanians in Ulcinj, and a combined Albanian-Ottoman force in the Podgorica-Spuž and Gusinje-Plav regions.[4][5] As such, Montenegro’s territorial gains were much smaller. Some Muslims and the Albanian population who lived near the then southern border were expelled from the towns of Podgorica and Spuž.[5] These populations resettled in Shkodër city and its environs.[6][7]

Notable battles[]

- Battle of Vučji Do (18 July 1876)

- Battle of Fundina (2 August 1876)

See also[]

- Montenegrin–Ottoman War (1852–53)

- Herzegovina Uprising (1875–77)

- Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78)

- Expulsion of the Albanians 1877–1878

- Battles for Plav and Gusinje (1879–1880)

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marko Miljanov; Jovan Čađenović; Ljubomir Zuković (1990). Primjeri čojstva i junaštva: Život i običaji Arbanasa ; Fragmenti ; Pisma ; Bibliografija. Crnogorska akademija nauka i umjetnosti.

У почетак рата, ја сам доша у Куче, у турску границу, те су се поб- унили Кучи и обрнули пушку на Турке. Паша турски је потпу- нио с војском Медун и фортице, Фундину, Коће, Затријебач и Ора'ово. У Ора'ово је метнуо Арбанасе, ...

- ^ Марко Миљанов (1904). Племе Кучи у народној причи и пјесми. p. 221.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mirko Petrović; Nićifor Dučić (1864). Junački spomenik, pjesne o najnovijim Tursko-Crnogorskim bojevima, spjevane od velikoga vojvode Mirka Petrović-Njegos̐a. U khjažeskoj štampariji. pp. 141–142.

- ^ Roberts, Elizabeth (2005). Realm of the Black Mountain: a history of Montenegro. London: Cornell University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780801446016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blumi, Isa (2003). "Contesting the edges of the Ottoman Empire: Rethinking ethnic and sectarian boundaries in the Malësore, 1878–1912". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 35 (2): 237–256. doi:10.1017/S0020743803000102. JSTOR 3879619. "What one sees over the course of the first ten years after Berlin was a gradual process of Montenegrin (Slav) expansion into areas that were still exclusively populated by Albanian-speakers. In many ways, some of these affected communities represented extensions of those in the Malisorë as they traded with one another throughout the year and even inter-married. Cetinje, eager to sustain some sense of territorial and cultural continuity, began to monitor these territories more closely, impose customs officials in the villages, and garrison troops along the frontiers. This was possible because, by the late 1880s, Cetinje had received large numbers of migrant Slavs from Austrian-occupied Herzegovina, helping to shift the balance of local power in Cetinje's favor. As more migrants arrived, what had been a quiet boundary region for the first few years, became the center of colonization and forced expulsion." ; p.254. footnote 38. "It must be noted that, throughout the second half of 1878 and the first two months of 1879, the majority of Albanian-speaking residents of Shpuza and Podgoritza, also ceded to Montenegro by Berlin, were resisting en masse. The result of the transfer of Podgoritza (and Antivari on the coast) was a flood of refugees. See, for instance, AQSH E143.D.1054.f.1 for a letter (dated 12 May 1879) to Dervish Pasha, military commander in Işkodra, detailing the flight of Muslims and Catholics from Podgoritza."

- ^ Gruber, Siegfried (2008). "Household structures in urban Albania in 1918". The History of the Family. 13 (2): 138–151. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2008.05.002.

- ^ Tošić, Jelena (2015). "City of the 'calm': Vernacular mobility and genealogies of urbanity in a southeast European borderland". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 15 (3): 391–408. doi:10.1080/14683857.2015.1091182.

Sources[]

- Владимир Ћоровић. "Пут на Берлински Конгрес". Историја Срба.

- Спиридон Гопчевић, „Црногорско-турски рат 1876. до 1878. године". Београд 1963

- William James Stillman (1997). Hercegovački ustanak i Crnogorsko-turski rat: 1876-1878. Službeni list SRJ. ISBN 978-86-355-0370-7.

- Montenegrin–Ottoman War (1876–1878)

- Conflicts in 1876

- Conflicts in 1877

- Conflicts in 1878

- Wars involving the Ottoman Empire

- Wars involving Montenegro

- 1870s in Montenegro

- 1870s in the Ottoman Empire

- 1876 in Europe

- 1877 in Europe

- 1878 in Europe

- Great Eastern Crisis