Macedonian Struggle

| Macedonian Struggle | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

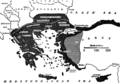

The geographical region of Macedonia which boundaries were defined in the second half of the 19th century. | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

|

SMAC BSRB |

|

|

[not verified in body] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

The Macedonian Struggle (Bulgarian: Македонска борба; Greek: Μακεδονικός Αγώνας; Macedonian: Борба за Македонија; Serbian: Борба за Македонију; Turkish: Makedonya Mücadelesi) was a series of social, political, cultural and military conflicts that were mainly fought between Greek and Bulgarian subjects who lived in Ottoman Macedonia between 1893 and 1908. The conflict was part of a wider rebel war in which revolutionary organizations of Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs all fought over Macedonia. Gradually the Greek and Bulgarian bands gained the upper hand, but the conflict was ended by the Young Turk Revolution in 1908.

Background[]

Initially the conflict was waged through educational and religious means, with a fierce rivalry developing between supporters of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (Greek speaking or Slavic speaking who generally identified as Greek), and supporters of the Bulgarian Exarchate, which had been established by the Ottomans in 1870.[2]

As Ottoman rule in the Balkans crumbled in the late 19th century, competition arose between Greeks and Bulgarians (and to a lesser extent also other ethnic groups such as Serbs, Aromanians and Albanians) over the multi-ethnic region of Macedonia.[2][need quotation to verify] The defeat of Greece in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 was a loss that appalled Greeks.[3] The Ethniki Eteria was dissolved by Prime Minister Theotokis. The region became at the times a constant battleground among various armed groups, while the Ottoman forces perpetuated atrocities against the Christian population. The fact that the Christian population of Macedonia, whatever they be Greek, Serb, Bulgarian or Aromanian, were engaged in more or less constant rebellion against the Ottoman Empire together with the revolutionary activities of Armenian nationalists in Anatolia, led many Ottoman officers to believe that the entire Christian population of the empire was disloyal and treasonous.[4]

Greco–Bulgarian relations in Ottoman Macedonia[]

In 1894, a Bulgarian organization known as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) had been founded and self-identified as being representative of all nations in Macedonia, along with anti-Ottoman revolutionaries in Thessaloniki, with the aim of liberating Macedonia and Thrace from Ottoman rule, potentially to join Bulgaria. IMRO was declared as a Macedonian organization open to all ethnic groups in Macedonia and, earlier on, IMRO claimed that it was fighting for the autonomy of Macedonia and not for annexation to Bulgaria. However, according to some authors and historians, it later became an agent serving Bulgarian interests in Balkan politics with the aim of eventually uniting the entirety of Macedonia with Bulgaria, first in struggles against the Ottoman Empire and later against the Serbian-led Yugoslav successor state controlling the territory of Vardar Macedonia and the Greek state which controlled the southern portion of the region.[5] One major event representing the culmination of these actions is the assassination of the Serbian King of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes during the inter-war period by an IMRO sniper, likely working for Bulgarian interests. In practice, most of the followers of the IMRO were local Macedonian Bulgarians, though they also had some pro-Bulgarian Aromanian supporters,[6][7][8] like Pitu Guli, Mitre The Vlach, Ioryi Mucitano and Alexandar Coshca.[9] Many of the members of the organization saw Macedonian autonomy as an intermediate step to unification with Bulgaria,[10][11] but others saw as their aim the creation of a Balkan federal state, with Macedonia as an equal member.[12]

Already from 1895 the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committees were formed in Sofia in order to reinforce the Bulgarian actions in Ottoman Empire. One of Komitadjis first activities was the capture of the predominantly Greek town of Meleniko (today Melnik, Bulgaria), but they couldn't hold it for more than a few hours.[13][14] Bulgarian bands destroyed the Pomak village of Dospat where they massacred local inhabitants.[14] This kind of activity alerted Greeks and Serbians, who made a farce of the slogan "Macedonia to Macedonians", being against the constitution of Macedonia as separate state.[15]

The situation in Macedonia became heated and started to affect European public opinion. In April 1903, a group called Gemidzhii with some assistance from the IMRO blew up the French ship Guadalquivir and the Ottoman Bank in the harbour of Thessaloniki. In August 1903, IMRO managed to organise an uprising (the Ilinden Uprising) in Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet. After the forming of the short-lived Kruševo Republic, the insurrection was suppressed by the Ottomans with the subsequent destruction of many villages and the devastation of large areas in Western Macedonia and around Kırk Kilise near Adrianople. The failure of the 1903 insurrection resulted in the eventual split of the IMRO into a left-wing (federalist) faction and a right-wing faction (centralists) which weakened the organization additionally.

Hellenic Macedonian Committee[]

In order to strengthen Greek efforts for Macedonia, the Hellenic Macedonian Committee was founded in 1903 by Stefanos Dragoumis and functioned under the leadership of wealthy publisher Dimitrios Kalapothakis. Its members included many Greek notables in addition to the fighters. Among its members were Ion Dragoumis and Pavlos Melas.[16] Its fighters were known as Makedonomachoi ("Macedonian fighters").[17]

Under these conditions, in 1904 a vicious guerrilla war broke as response of IMRO activities between Bulgarian and Greek bands within Ottoman Macedonia. The Bishop of Kastoria, Germanos Karavangelis, who was sent to Macedonia by Nikolaos Mavrokordatos, the ambassador of Greece, and Ion Dragoumis, the consul of Greece in Monastir, realised that it was time to act in a more efficient way and began to organise the intensification of the Greek opposition.

While Dragoumis concerned himself with the financial organisation of the efforts, the central figure in the military struggle was the very capable Cretan officer Georgios Katechakis.[18] Bishop Germanos Karavangelis travelled to raise morale and encourage the Greek population to take action against the IMRO. Many committees were also formed to promote the Greek national interests.

Katechakis and Karavangelis succeeded in the recruitment and organization of guerrilla groups that were later reinforced with volunteers from Greece. Volunteers often came from Crete and the Mani area of the Peloponnese. They even recruited former IMRO members, taking advantage of their political and/or personal disputes within the organisation. Additionally, officers of the Hellenic Army were encouraged to join the struggle to provide experienced leadership as many had served in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. Many of which would ultimately join and provided a logistical advantage to the Makedonomachoi. The Macedonian Greeks, however, would form the core of the fighting force and proved to be the most important fighters due to their knowledge of the region's geography and some possessing knowledge of the Bulgarian language. Many Macedonian Greeks, such as Periklis Drakos, were also involved in the smuggling and stashing of weapons and ammunition around the region.

Greek activity[]

The Greek state became concerned, not only because of Bulgarian penetration in Macedonia but also due to Serbian interests, which were concentrated mainly in Skopje and Bitola area. The rioting in Macedonia and especially the death of Pavlos Melas in 1904 (he was the first Greek officer to enter Macedonia with guerrillas and was killed in battle with the Ottoman army) caused intense nationalistic feelings in Greece. This led to the decision to send more guerrilla troops in order to thwart Bulgarian efforts to bring all of the Slavic-speaking population of Macedonia on their side.

The Greek General Consulate in Thessaloniki, under Lambros Koromilas, became the centre of the struggle, coordinating the guerrilla troops, distributing military material and nursing the wounded. Fierce conflicts between the Greeks and Bulgarians started in the area of Kastoria, in the Giannitsa Lake area, and elsewhere. During 1905, guerilla activity increased and the Makedonomachoi gained significant advantage within 10 months, extending their control towards the areas of Mariovo and East Macedonia, Kastanohoria (near Kastoria), the plains north and south of Florina and the routes around Monastir.[19] However, from early 1906 the situation became critical and the forces of the Makedonomachoi were forced to withdraw from various areas. Their manpower during that period was reduced from 1,000 to ca. 200, perhaps a little more than the Komitadjis, but nevertheless the groups of Tellos Agras and Ioannis Demestichas had some success in the marsh of Giannitsa.[19] There were great advances of the Serb forces, joined by Muslim Slavs, in summer of 1906 in the northern areas of the Sanjak of Skopje.[20]

While the guerrilla groups confronted the Ottoman Army, the Ottoman administration often ignored the activity of the Greek guerrillas,[21] and according to Dakin assisted them against the Bulgarians outright.[15] However, once the subversive potential of the Bulgarian side had been neutralised, Ottoman policy ended the favourable neutrality to the Greek side and embarked upon "relentless persecutions" against the andartes, though even then their main interest was to "suppress the Bulgarian gangs"[22]

Crimes[]

War crimes were committed by both sides during the Macedonian struggle. According to a 1900 British report compiled by Alfred Biliotti, who is considered to have heavily relied on Greek intelligence agents,[23] starting from 1897, the members of the Exarchist committees had embarked upon a systematic and extensive campaign of executions of the leading members of the Greek side.[24] Moreover, Bulgarian Komitadjis, pursued a campaign of extermination of Greek and Serbian teachers and clergy.[25] On the other hand, there were attacks by Greek Andartes on many Macedonian Bulgarian villages, with the aim of forcing their inhabitants to switch their allegiance from the Exarchate back to the Patriarchate and accept Greek priest and teachers,[26] but they also carried out massacres against the civilian population,[27] especially in the central parts of Macedonia in 1905[28] and in 1906.[29] One of the notable cases was the massacre[30] at the village Zagorichani (today Vasiliada, Greece), which was an Bulgarian Exarchist stronghold[15] near Kastoria on 25 March 1905, where between 60 and 78 villagers were killed by Greek bands.[29][31]

According to British reports on political crimes (including the above-mentioned Biliotti report), during the period from 1897 to 1912 over 4000 political murders were committed (66 before 1901, 200 between 1901 and 1903, 3300 between 1903 and 1908 and 600 between 1908 and 1912), excluding those killed during the Ilinden uprising and the members of the Bulgarian and Greek bands. Of those who were killed, 53% were Bulgarians, 33.5% were Greeks, Serbs and Aromanians together 3.5% and 10% were of unknown nationality.[32]

These conflicts ended after the revolution of Young Turks in July 1908, as they promised to respect all ethnicities and religions, and to provide a constitution.

Consequences[]

The success of Greek efforts in Macedonia was an experience that gave confidence to the country. It helped develop an intention to annex Greek-speaking areas, and bolster Greek presence in the still Ottoman-ruled Macedonia.

The events in Macedonia, specifically the consequences of the conflicts between Greek and Bulgarian national activists, including Greek massacres against the Bulgarian population in 1905 and 1906, gave rise to pogroms against the ca. 70,000-80,000 strong Greek communities that lived in Bulgaria, who were considered to share responsibility (including the support given to the guerrillas by some Bulgarian Greeks) for the actions of the Greek guerrilla groups.[31][33]

Nevertheless, the Young Turk movement resulted in a few instances of collaboration between Greek and Bulgarian bands, while this time the official policy in both countries continue to support the penetration of armed fighters into Ottoman Macedonia, but without having fully ensured that there would be no attacks on each other.[34]

Legacy[]

The Greek fighters were portrayed by Greek writer Penelope Delta in her novel Τά μυστικά τοῦ Βάλτου (Ta Mystiká tou Váltou – The Secrets of the Swamp), as well as in the book of memoirs Ὁ Μακεδονικός Ἀγών (The Macedonian Struggle) by Germanos Karavangelis, while on the other side, the IMRO and their activities are depicted in the book Confessions of a Macedonian Bandit: A Californian in the Balkan Wars, written by Albert Sonnichsen, an American volunteer in the IMRO during the Macedonian Struggle.

See also[]

- Macedonian Question

- Macedonian Revolution (disambiguation)

- History of Modern Greece

Notes[]

- ^ Sfetas, Spyridon (2001). "Το ιστορικό πλαίσιο των ελληνο-ρουμανικών πολιτικών σχέσεων (1866-1913)" [The Historical Context of Greco-Romanian political relations (1866–1913)]. Makedonika (in Greek). Society for Macedonian Studies. 33 (1): 23–48. doi:10.12681/makedonika.278. ISSN 0076-289X. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clogg, Richard. A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press, 1992. 257 pp. p.81.

- ^ Clogg, Richard. A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press, 1992. p. 71.

- ^ Akmeşe 2005, pp. 50–53.

- ^ Encyclopedia of terrorism, Cindy C. Combs, Martin W. Slann, Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 1438110197, p. 135.

- ^ Andrew Rossos, Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History, Hoover Press, 2013, ISBN 081794883X,p. 105.

- ^ Philip Jowett, Armies of the Balkan Wars 1912–13: The priming charge for the Great War, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012, ISBN 184908419X, p. 21.

- ^ Raymond Detrez, 2014, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 1442241802, p. 520.

- ^ "The Aromanians and IMRO (Nikola Minov) - Republic of Macedonia - Balkans". Scribd.

- ^ Идеята за автономия като тактика в програмите на национално-освободителното движение в Македония и Одринско (1893-1941), Димитър Гоцев, 1983, Изд. на Българска Академия на Науките, София, 1983, c. 34.; in English: The idea for autonomy as a tactics in the programs of the National Liberation movements in Macedonia and Adrianople regions 1893-1941", Sofia, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Dimitar Gotsev, 1983, p 34. Among others, there are used the memoirs of the IMRO revolutionary Kosta Tsipushev, where he cited Delchev, that the autonomy then was only tactics, aiming future unification with Bulgaria. (55. ЦПА, ф. 226); срв. К. Ципушев. 19 години в сръбските затвори, СУ Св. Климент Охридски, 2004, ISBN 954-91083-5-X стр. 31-32. in English: Kosta Tsipushev, 19 years in Serbian prisons, Sofia University publishing house, 2004, ISBN 954-91083-5-X, p. 31-32.

- ^ Таjните на Македонија. Се издава за прв пат, Скопје 1999. in Macedonian – Ете како ја објаснува целта на борбата Гоце Делчев во 1901 година: "...Треба да се бориме за автономноста на Македанија и Одринско, за да ги зачуваме во нивната целост, како еден етап за идното им присоединување кон општата Болгарска Татковина". In English – How Gotse Delchev explained the aim of the struggle against the Ottomans in 1901: "...We have to fight for autonomy of Macedonia and Adrianople regions as a stage for their future unification with our common fatherland, Bulgaria."

- ^ The last interview with the leader of IMRO, Ivan Michailov in 1989 - newspaper 'Democratsia', Sofia, 8 January 2001, pp. 10-11. Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sherman, Laura Beth (1980). Fires on the mountain: the Macedonian revolutionary movement and the kidnapping of Ellen Stone. New York: Columbia U.P. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-914710-55-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Le meurtre du prêtre comme violence inaugurale (Bulgarie 1872, Macédoine 1900)". http://balkanologie. IX (1–2). December 2005. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dakin, Douglas (1966). The Greek struggle in Macedonia, 1897-1913. Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 48, 224 and p.337.

- ^ Konstantinos Vakalopoulos, Historia tou voreiou hellenismou, vol 2, 1990, pp. 429-430

- ^ Keith S. Brown; Yannis Hamilakis (2003). The Usable Past: Greek Metahistories. Lexington Books. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7391-0384-5.

- ^ Bulgarian Historical Review, vol 31, 1-4, 2003, p 117 "Only a few days later -on November 1- Katehakis arrived in Macedonia as Melas' successor"

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gounaris, Basil C. "National Claims, Conflicts and Developments in Macedonia, 1870-1912" (PDF). macedonian-heritage.gr. p. 194. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Vemund Aarbakke (2003). Ethnic rivalry and the quest for Macedonia, 1870-1913. East European Monographs. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-88033-527-0.

- ^ M. Şükrü Hanioğlu (8 March 2010). A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4008-2968-2.

- ^ Gounaris, Basil C. "National Claims, Conflicts and Developments in Macedonia, 1870-1912" (PDF). macedonian-heritage.gr. p. 196. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ David Barchard, The Fearless and Self-Reliant Servant: The Life and Career of Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833-1895), p.50

- ^ Gounaris, Basil C. "National Claims, Conflicts and Developments in Macedonia, 1870-1912" (PDF). macedonian-heritage.gr. p. 189. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Jezernik, Božidar (2004). Wild Europe: the Balkans in the gaze of Western travellers. London: Saqi [u.a.] p. 183. ISBN 978-0-86356-574-8.

- ^ Hazell's Annual. Hazell, Watson and Viney. 1908. p. 574.; Edmund Burke (1907). The Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year. 148. Longmans, Green. p. 334.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge. 27. Encyclopedia Americana Corporation. 1920. p. 194.

- ^ Henry Noël Brailsford (1906). Macedonia; its races and their future. Metheun. pp. 215–216.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Theodora Dragostinova (17 March 2011). Between Two Motherlands: Nationality and Emigration among the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900–1949. Cornell University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-8014-6116-3.

- ^ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1906). Parliamentary Papers, House of Commons and Command. 137. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Macedonian question, 1893-1908, from Western sources; Nadine Lange-Akhund; 1998 p.279

- ^ Basil C. Gounaris; Preachers of God and martyrs of the Nation: The politics of murder in Ottoman Macedonia in the early 20th century; Balkanologie, Vol. IX, December 2005

- ^ Theodora Dragostinova (2011). Between Two Motherlands: Nationality and Emigration Among the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900-1949. Cornell University Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-0-8014-6116-3.

New Greek massacres of Bulgarians in Macedonia in 1906 led to a repetition of anti-Greek violence in the Principality of Bulgaria

- ^ Gounaris, Basil C. "National Claims, Conflicts and Developments in Macedonia, 1870-1912" (PDF). macedonian-heritage.gr. p. 201. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

References[]

- Christopoulos, Georgios; Bastias, Ioannis (1977). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Εθνους: Νεώτερος Ελληνισμός απο το 1881 ως 1913 [History of the Greek Nation: Modern Greece from 1881 until 1913] (in Greek). XIV. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon.

- Koliopoulos, Ioannis: History of Greece from 1800, Nation, State and Society, Thessaloniki, 2000 ISBN 960-288-072-4

- Dakin, Douglas: "The Greek Struggle in Macedonia 1897–1913", 1993 ISBN 9607387007

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos: "History of the Greek Nation 1204–1985" (in Greek language)

- Karavangelis, Germanos: "The Macedonian Struggle" (Memoirs)

- Sonnichsen, Albert: Confessions of a Macedonian Bandit: A Californian in the Balkan Wars, The Narrative Press, ISBN 1-58976-237-1 (the Macedonian struggle from a perspective of an American volunteer in IMRO)

- Rappoport, Alfred: Au pays des martyrs. Notes et souvenirs d'un ancien consul-général d'Autriche-Hongrie en Macédoine (1904–1909). Librarie Universitaire J. Gamber, Paris, 1927. Memoirs of the General Consul of Austro-Hungary in Macedonia. Cat. No. 7029530203814.

- Richards, Louise Parker (November 1903). "What the Macedonian Trouble Is". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. VII: 4066–4073. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Akmeşe, Handan Nezir (2005). The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to World War I. London: IB Tauris.

External links[]

- Macedonian Struggle

- Macedonia under the Ottoman Empire

- Kosovo Vilayet

- Manastir Vilayet

- Salonica Vilayet

- Wars involving the Ottoman Empire

- Wars involving Bulgaria

- Wars involving Serbia

- Wars involving Greece

- Conflicts in 1901

- Conflicts in 1902

- Conflicts in 1903

- Conflicts in 1904

- Conflicts in 1905

- Conflicts in 1906

- Conflicts in 1907

- Conflicts in 1908

- 1893 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1904 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1905 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1906 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1907 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1908 in the Ottoman Empire

- Greece–Ottoman Empire relations

- Bulgaria–Greece relations

- Ion Dragoumis

- Mass murder in 1901

- Mass murder in 1903

- Mass murder in 1904

- Mass murder in 1905

- Mass murder in 1906