Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

| Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Turkish War of Independence | |||||||||

Greek infantry charge near the River Gediz | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by:

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

Armenian Legion[7] | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Organization 1922[11]

|

Organization 1922[11]

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

* 20,826 Greek prisoners were taken. Of those about 740 officers and 13,000 soldiers arrived in Greece during the prisoner exchange in 1923. The rest presumably died in captivity and are listed among the "missing".[23]

| |||||||||

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922[c] was fought between Greece and the Turkish National Movement during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I, between May 1919 and October 1922.

The Greek campaign was launched primarily because the western Allies, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, recently defeated in World War I, as Anatolia had been part of Ancient Greece and the Byzantine Empire before the Ottomans captured the area. The armed conflict started when the Greek forces landed in Smyrna (now İzmir), on 15 May 1919. They advanced inland and took control of the western and northwestern part of Anatolia, including the cities of Manisa, Balıkesir, Aydın, Kütahya, Bursa and Eskişehir. Their advance was checked by Turkish forces at the Battle of Sakarya in 1921. The Greek front collapsed with the Turkish counter-attack in August 1922, and the war effectively ended with the recapture of Smyrna by Turkish forces and the great fire of Smyrna.

As a result, the Greek government accepted the demands of the Turkish National Movement and returned to its pre-war borders, thus leaving East Thrace and Western Anatolia to Turkey. The Allies abandoned the Treaty of Sèvres to negotiate a new treaty at Lausanne with the Turkish National Movement. The Treaty of Lausanne recognized the independence of the Republic of Turkey and its sovereignty over Anatolia, Istanbul, and Eastern Thrace. The Greek and Turkish governments agreed to engage in a population exchange.

Background[]

Geopolitical context[]

The geopolitical context of this conflict is linked to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire which was a direct consequence of World War I and involvement of the Ottomans in the Middle Eastern theatre. The Greeks received an order to land in Smyrna by the Triple Entente as part of the partition. During this war, the Ottoman government collapsed completely and the Ottoman Empire was divided amongst the victorious Entente powers with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres on August 10, 1920.

There were a number of secret agreements regarding the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. The Triple Entente had made contradictory promises about post-war arrangements concerning Greek hopes in Asia Minor.[27]

The western Allies, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire if Greece entered the war on the Allied side.[28] These included Eastern Thrace, the islands of Imbros (İmroz, since 29 July 1979 Gökçeada) and Tenedos (Bozcaada), and parts of western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna, which contained sizable ethnic Greek populations.

The Italian and Anglo-French repudiation of the Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne signed on April 26, 1917, which settled the "Middle Eastern interest" of Italy, was overridden with the Greek occupation, as Smyrna (İzmir) was part of the territory promised to Italy. Before the occupation the Italian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, angry about the possibility of the Greek occupation of Western Anatolia, left the conference and did not return to Paris until May 5. The absence of the Italian delegation from the Conference ended up facilitating Lloyd George's efforts to persuade France and the United States to support Greece and prevent Italian operations in Western Anatolia.

According to some historians, it was the Greek occupation of Smyrna that created the Turkish National movement. Arnold J. Toynbee argues: "The war between Turkey and Greece which burst out at this time was a defensive war for safeguarding of the Turkish homelands in Anatolia. It was a result of the Allied policy of imperialism operating in a foreign state, the military resources and powers of which were seriously under-estimated; it was provoked by the unwarranted invasion of a Greek army of occupation."[29] According to others, the landing of the Greek troops in Smyrna was part of Eleftherios Venizelos's plan, inspired by the Megali Idea, to liberate the large Greek populations in the Asia Minor.[30] Prior to the Great Fire of Smyrna, Smyrna had a bigger Greek population than the Greek capital, Athens. Athens, before the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey, had a population of 473,000,[31] while Smyrna, according to Ottoman sources, in 1910, had a Greek population exceeding 629,000.[32]

The Greek community in Anatolia[]

| Distribution of Nationalities in Ottoman Empire (Anatolia),[33] Ottoman Official Statistics, 1910 | |||||||

| Provinces | Turks | Greeks | Armenians | Jews | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| İstanbul (Asiatic shore) | 135,681 | 70,906 | 30,465 | 5,120 | 16,812 | 258,984 | |

| İzmit | 184,960 | 78,564 | 50,935 | 2,180 | 1,435 | 318,074 | |

| Aydın (Izmir) | 974,225 | 629,002 | 17,247 | 24,361 | 58,076 | 1,702,911 | |

| Bursa | 1,346,387 | 274,530 | 87,932 | 2,788 | 6,125 | 1,717,762 | |

| Konya | 1,143,335 | 85,320 | 9,426 | 720 | 15,356 | 1,254,157 | |

| Ankara | 991,666 | 54,280 | 101,388 | 901 | 12,329 | 1,160,564 | |

| Trabzon | 1,047,889 | 351,104 | 45,094 | – | – | 1,444,087 | |

| Sivas | 933,572 | 98,270 | 165,741 | – | – | 1,197,583 | |

| Kastamonu | 1,086,420 | 18,160 | 3,061 | – | 1,980 | 1,109,621 | |

| Adana | 212,454 | 88,010 | 81,250 | – | 107,240 | 488,954 | |

| Biga | 136,000 | 29,000 | 2,000 | 3,300 | 98 | 170,398 | |

| Total % |

8,192,589 75.7% |

1,777,146 16.42% |

594,539 5.5% |

39,370 0.36% |

219,451 2.03% |

10,823,095 | |

| Ecumenical Patriarchate Statistics, 1912 | |||||||

| Total % |

7,048,662 72.7% |

1,788,582 18.45% |

608,707 6.28% |

37,523 0.39% |

218,102 2.25% |

9,695,506 | |

One of the reasons proposed by the Greek government for launching the Asia Minor expedition was that there was a sizeable Greek-speaking Orthodox Christian population inhabiting Anatolia that needed protection. Greeks had lived in Asia Minor since antiquity, and before the outbreak of World War I, up to 2.5 million Greeks lived in the Ottoman Empire.[34] The suggestion that the Greeks constituted the majority of the population in the lands claimed by Greece has been contested by a number of historians. Cedric James Lowe and Michael L. Dockrill also argued that Greek claims about Smyrna were at best debatable, since Greeks constituted perhaps a bare majority, more likely a large minority in the Smyrna Vilayet, "which lay in an overwhelmingly Turkish Anatolia."[35] Precise demographics are further obscured by the Ottoman policy of dividing the population according to religion rather than descent, language, or self-identification. On the other hand, contemporaneous British and American statistics (1919) support the point that the Greek element was the most numerous in the region of Smyrna, counting 375,000, while Muslims were 325,000.[36][37]

Greek Prime Minister Venizelos stated to a British newspaper that "Greece is not making war against Islam, but against the anachronistic Ottoman Government, and its corrupt, ignominious, and bloody administration, with a view to expelling it from those territories where the majority of the population consists of Greeks."[38]

To an extent, the above danger may have been overstated by Venizelos as a negotiating card on the table of Sèvres, in order to gain the support of the Allied governments. For example, the Young Turks were not in power at the time of the war, which makes such a justification less straightforward. Most of the leaders of that regime had fled the country at the end of World War I and the Ottoman government in Constantinople was already under British control. Furthermore, Venizelos had already revealed his desires for annexation of territories from the Ottoman Empire in the early stages of World War I, before these massacres had taken place. In a letter sent to Greek King Constantine in January 1915, he wrote that: "I have the impression that the concessions to Greece in Asia Minor ... would be so extensive that another equally large and not less rich Greece will be added to the doubled Greece which emerged from the victorious Balkan wars."[39]

Through its failure, the Greek invasion may have instead exacerbated the atrocities that it was supposed to prevent. Arnold J. Toynbee blamed the policies pursued by Great Britain and Greece, and the decisions of the Paris Peace conference as factors leading to the atrocities committed by both sides during and after the war: "The Greeks of 'Pontus' and the Turks of the Greek occupied territories, were in some degree victims of Mr. Venizelos's and Mr. Lloyd George's original miscalculations at Paris."[40]

Greek irredentism[]

One of the main motivations for initiating the war was to realize the Megali (Great) Idea, a core concept of Greek nationalism. The Megali Idea was an irredentist vision of a restoration of a Greater Greece on both sides of the Aegean that would incorporate territories with Greek populations outside the borders of the Kingdom of Greece, which was initially very small — roughly half the size of the present-day Greek Republic. From the time of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, the Megali Idea had played a major role in Greek politics. Greek politicians, since the independence of the Greek state, had made several speeches on the issue of the "historic inevitability of the expansion of the Greek Kingdom."[41] For instance, Greek politician Ioannis Kolettis voiced this conviction in the assembly in 1844: "There are two great centres of Hellenism. Athens is the capital of the Kingdom. Constantinople is the great capital, the City, the dream and hope of all Greeks."[citation needed]

The Great Idea was not merely the product of 19th century nationalism. It was, in one of its aspects, deeply rooted in many Greeks' religious consciousnesses. This aspect was the recovery of Constantinople for Christendom and the reestablishment of the Christian Byzantine Empire which had fallen in 1453. "Ever since this time the recovery of St. Sophia and the City had been handed down from generation to generation as the destiny and aspiration of the Greek Orthodox."[41] The Megali Idea, besides Constantinople, included most traditional lands of the Greeks including Crete, Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, Thrace, the Aegean Islands, Cyprus, the coastlands of Asia Minor and Pontus on the Black Sea. Asia Minor was an essential part of the Greek world and an area of enduring Greek cultural dominance. In antiquity, from late Bronze Age up to the Roman conquest, Greek city-states had even exercised political control of most of the region, except the period ca. 550–470 BC when it was part of the Achaimenid Persian Empire. Later, during Middle Ages, the region had belonged to the Byzantine Empire until the 12th century, when the first Seljuk Turk raids reached it.

The National Schism in Greece[]

This section does not cite any sources. (August 2017) |

The National Schism in Greece was the deep split of Greek politics and society between two factions, the one led by Eleftherios Venizelos and the other by King Constantine, that predated World War I but escalated significantly over the decision on which side Greece should support during the war.

The United Kingdom had hoped that strategic considerations might persuade Constantine to join the cause of the Allies, but the King and his supporters insisted on strict neutrality, especially whilst the outcome of the conflict was hard to predict. In addition, family ties and emotional attachments made it difficult for Constantine to decide which side to support during World War I. The King's dilemma was further increased when the Ottomans and the Bulgarians, both having grievances and aspirations against the Greek Kingdom, joined the Central Powers.

Though Constantine did remain decidedly neutral, Prime Minister of Greece Eleftherios Venizelos had from an early point decided that Greece's interests would be best served by joining the Entente and started diplomatic efforts with the Allies to prepare the ground for concessions following an eventual victory. The disagreement and the subsequent dismissal of Venizelos by the King resulted in a deep personal rift between the two, which spilled over into their followers and the wider Greek society. Greece became divided into two radically opposed political camps, as Venizelos set up a separate state in Northern Greece, and eventually, with Allied support, forced the King to abdicate. In May 1917, after the exile of Constantine, Venizélos returned to Athens and allied with the Entente. Greek military forces (though divided between supporters of the monarchy and supporters of "Venizelism") began to take part in military operations against the Bulgarian Army on the border.

The act of entering the war and the preceding events resulted in a deep political and social division in post–World War I Greece. The country's foremost political formations, the Venizelist Liberals and the Royalists, already involved in a long and bitter rivalry over pre-war politics, reached a state of outright hatred towards each other. Both parties viewed the other's actions during the First World War as politically illegitimate and treasonous. This enmity inevitably spread throughout Greek society, creating a deep rift that contributed decisively to the failed Asia Minor campaign and resulted in much social unrest in the inter war years.

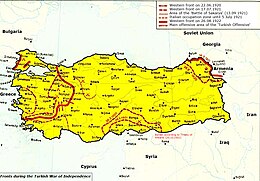

Greek expansion[]

The military aspect of the war began with the Armistice of Mudros. The military operations of the Greco-Turkish war can be roughly divided into three main phases: the first phase, spanning the period from May 1919 to October 1920, encompassed the Greek Landings in Asia Minor and their consolidation along the Aegean Coast. The second phase lasted from October 1920 to August 1921, and was characterised by Greek offensive operations. The third and final phase lasted until August 1922, when the strategic initiative was held by the Turkish Army.[citation needed]

Landing at Smyrna (May 1919)[]

On May 15, 1919, twenty thousand[42] Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna and took control of the city and its surroundings under cover of the Greek, French, and British navies. Legal justifications for the landings was found in the article 7 of the Armistice of Mudros, which allowed the Allies "to occupy any strategic points in the event of any situation arising which threatens the security of Allies."[43] The Greeks had already brought their forces into Eastern Thrace (apart from Constantinople and its region).

The Christian population of Smyrna (mainly Greeks and Armenians), according to different sources, either formed a minority[35][44] or a majority[45] compared to Muslim Turkish population of the city. The Greek army also consisted of 2,500 Armenian volunteers.[46] The majority of the Greek population residing in the city greeted the Greek troops as liberators.[47]

Greek summer offensives (Summer 1920)[]

During the summer of 1920, the Greek army launched a series of successful offensives in the directions of the Büyük Menderes River (Meander) Valley, Bursa (Prusa) and Alaşehir (Philadelphia). The overall strategic objective of these operations, which were met by increasingly stiff Turkish resistance, was to provide strategic depth to the defence of Izmir (Smyrna). To that end, the Greek zone of occupation was extended over all of Western and most of North-Western Anatolia.

Treaty of Sèvres (August 1920)[]

In return for the contribution of the Greek army on the side of the Allies, the Allies supported the assignment of eastern Thrace and the millet of Smyrna to Greece. This treaty ended the First World War in Asia Minor and, at the same time, sealed the fate of the Ottoman Empire. Henceforth, the Ottoman Empire would no longer be a European power.

On August 10, 1920, the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres ceding to Greece Thrace, up to the Chatalja lines. More importantly, Turkey renounced to Greece all rights over Imbros and Tenedos, retaining the small territories of Constantinople, the islands of Marmara, and "a tiny strip of European territory". The Straits of Bosporus were placed under an International Commission, as they were now open to all.

Turkey was furthermore forced to transfer to Greece "the exercise of her rights of sovereignty" over Smyrna in addition to "a considerable Hinterland, merely retaining a 'flag over an outer fort'." Though Greece administered the Smyrna enclave, its sovereignty remained, nominally, with the Sultan. According to the provisions of the Treaty, Smyrna was to maintain a local parliament and, if within five years time she asked to be incorporated within the Kingdom of Greece, the provision was made that the League of Nations would hold a plebiscite to decide on such matters.

The treaty was never ratified by the Ottoman Empire[48][49] nor Greece.[50][better source needed]

Greek advance (October 1920)[]

In October 1920, the Greek army advanced further east into Anatolia, with the encouragement of Lloyd George, who intended to increase pressure on the Turkish and Ottoman governments to sign the Treaty of Sèvres. This advance began under the Liberal government of Eleftherios Venizelos, but soon after the offensive began, Venizelos fell from power and was replaced by Dimitrios Gounaris. The strategic objective of these operations was to defeat the Turkish Nationalists and force Mustafa Kemal into peace negotiations. The advancing Greeks, still holding superiority in numbers and modern equipment at this point, had hoped for an early battle in which they were confident of breaking up ill-equipped Turkish forces. Yet they met with little resistance, as the Turks managed to retreat in an orderly fashion and avoid encirclement. Churchill said: "The Greek columns trailed along the country roads passing safely through many ugly defiles, and at their approach the Turks, under strong and sagacious leadership, vanished into the recesses of Anatolia."[51]

Change in Greek government (November 1920)[]

During October 1920, King Alexander, who had been installed on the Greek throne on 11 June 1917 when his father Constantine was pushed into exile by the Venizelists, was bitten by a monkey kept at the Royal Gardens and died within days from sepsis.[52] After King Alexander died without heirs, the legislative elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1920, suddenly became the focus of a new conflict between the supporters of Venizelos and the Royalists. The anti-Venizelist faction campaigned on the basis of accusations of internal mismanagement and authoritarian attitudes of the government, which, due to the war, had stayed in power without elections since 1915. At the same time they promoted the idea of disengagement in Asia Minor, without though presenting a clear plan as to how this would happen. On the contrary, Venizelos was identified with the continuation of a war that did not seem to go anywhere. The majority of the Greek people were both war-weary and tired of the almost dictatorial regime of the Venizelists, so opted for change. To the surprise of many, Venizelos won only 118 out of the total 369 seats. The crushing defeat obliged Venizelos and a number of his closest supporters to leave the country. To this day his rationale to call elections at that time is questioned.

The new government under Dimitrios Gounaris prepared for a plebiscite on the return of King Constantine. Noting the King's hostile stance during World War I, the Allies warned the Greek government that if he should be returned to the throne they would cut off all financial and military aid to Greece .[citation needed]

A month later a plebiscite called for the return of King Constantine. Soon after his return, the King replaced many of the World War I Venizelist officers and appointed inexperienced monarchist officers to senior positions. The leadership of the campaign was given to Anastasios Papoulas, while King Constantine himself assumed nominally the overall command. The High Commissioner in Smyrna, Aristeidis Stergiadis, however was not removed. In addition, many of the remaining Venizelist officers resigned, appalled by the regime change.[citation needed]

A group of officers, headed by Georgios Kondylis, formed in Constantinople a "National Defence" organization, which reinforced with Venizelist deserters, soon started to criticize the royalist government of Athens.

The Greek Army which had secured Smyrna and the Asia Minor coast was purged of most of Venizelos's supporters, while it marched on Ankara. However, tension inside the Army between the two factions remained.

Battles of İnönü (December 1920 – March 1921)[]

By December 1920, the Greeks had advanced on two fronts, approaching Eskişehir from the North West and from Smyrna, and had consolidated their occupation zone. In early 1921 they resumed their advance with small scale reconnaissance incursions that met stiff resistance from entrenched Turkish Nationalists, who were increasingly better prepared and equipped as a regular army.

The Greek advance was halted for the first time at the First Battle of İnönü on January 11, 1921. Even though this was a minor confrontation involving only one Greek division, it held political significance for the fledgling Turkish revolutionaries. This development led to Allied proposals to amend the Treaty of Sèvres at a conference in London where both the Turkish Revolutionary and Ottoman governments were represented.

Although some agreements were reached with Italy, France and Britain, the decisions were not agreed to by the Greek government, who believed that they still retained the strategic advantage and could yet negotiate from a stronger position. The Greeks initiated another attack on March 27, the Second Battle of İnönü, where the Turkish troops fiercely resisted and finally halted the Greeks on March 30. The British favoured a Greek territorial expansion but refused to offer any military assistance in order to avoid provoking the French.[citation needed] The Turkish forces received arms assistance from Soviet Russia.[53]

Shift of support towards Turkish Revolutionaries[]

By this time all other fronts had been settled in favour of the Turks,[citation needed] freeing more resources for the main threat of the Greek Army. France and Italy concluded private agreements with the Turkish revolutionaries in recognition of their mounting strength.[54] They viewed Greece as a British client, and sold military equipment to the Turks. The new Bolshevik government of Russia became friendly to the Turkish revolutionaries, as shown in the Treaty of Moscow (1921). The Bolsheviks supported Mustafa Kemal and his forces with money and ammunition.[55][56] In 1920 alone, Bolshevik Russia supplied the Kemalists with 6,000 rifles, over 5 million rifle cartridges, and 17,600 shells as well as 200.6 kg (442.2 lb) of gold bullion. In the subsequent two years the amount of aid increased.[57]

Battle of Afyonkarahisar-Eskişehir (July 1921)[]

Between 27 June and 20 July 1921, a reinforced Greek army of nine divisions launched a major offensive, the greatest thus far, against the Turkish troops commanded by Ismet Inönü on the line of Afyonkarahisar-Kütahya-Eskişehir. The plan of the Greeks was to cut Anatolia in two, as the above towns were on the main rail-lines connecting the hinterland with the coast. Eventually, after breaking the stiff Turkish defences, they occupied these strategically important centres. Instead of pursuing and decisively crippling the nationalists' military capacity, the Greek Army halted. In consequence, and despite their defeat, the Turks managed to avoid encirclement and made a strategic retreat on the east of the Sakarya River, where they organised their last line of defence.

This was the major decision that sealed the fate of the Greek campaign in Anatolia. The state and Army leadership, including King Constantine, Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, and General Anastasios Papoulas, met at Kütahya where they debated the future of the campaign. The Greeks, with their faltering morale rejuvenated, failed to appraise the strategic situation that favoured the defending side; instead, pressed for a 'final solution', the leadership was polarised into the risky decision to pursue the Turks and attack their last line of defence close to Ankara. The military leadership was cautious and asked for more reinforcements and time to prepare, but did not go against the politicians. Only a few voices supported a defensive stance, including Ioannis Metaxas. Constantine by this time had little actual power and did not argue either way. After a delay of almost a month that gave time to the Turks to organise their defence, seven of the Greek divisions crossed east of the Sakarya River.

Battle of Sakarya (August and September 1921)[]

Following the retreat of the Turkish troops under Ismet Inönü in the battle of Kütahya-Eskişehir the Greek Army advanced afresh to the Sakarya River (Sangarios in Greek), less than 100 kilometres (62 mi) west of Ankara. Constantine's battle cry was "to Angira" and the British officers were invited, in anticipation, to a victory dinner in the city of Kemal.[58] It was envisaged that the Turkish Revolutionaries, who had consistently avoided encirclement would be drawn into battle in defence of their capital and destroyed in a battle of attrition.

Despite the Soviet help, supplies were short as the Turkish army prepared to meet the Greeks. Owners of private rifles, guns and ammunition had to surrender them to the army and every household was required to provide a pair of underclothing and sandals.[59] Meanwhile, the Turkish parliament, not happy with the performance of Ismet Inönü as the Commander of the Western Front, wanted Mustafa Kemal and Chief of General Staff Fevzi Çakmak to take control.

Greek forces marched 200 kilometres (120 mi) for a week through the desert to reach attack positions, so the Turks could see them coming. Food supplies were 40 tons of bread and salt, sugar and tea, the rest to be found on the way.[60]

The advance of the Greek Army faced fierce resistance which culminated in the 21-day Battle of Sakarya (August 23 – September 13, 1921). The Turkish defense positions were centred on series of heights, and the Greeks had to storm and occupy them. The Turks held certain hilltops and lost others, while some were lost and recaptured several times over. Yet the Turks had to conserve men, for the Greeks held the numerical advantage.[61] The crucial moment came when the Greek army tried to take Haymana, 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of Ankara, but the Turks held out. Greek advances into Anatolia had lengthened their lines of supply and communication and they were running out of ammunition. The ferocity of the battle exhausted both sides but the Greeks were the first to withdraw to their previous lines. The thunder of cannon was plainly heard in Ankara throughout the battle.

That was the furthest in Anatolia the Greeks would advance, and within a few weeks they withdrew in an orderly manner back to the lines that they had held in June. The Turkish Parliament awarded both Mustafa Kemal and Fevzi Çakmak with the title of Field Marshal for their service in this battle. To this day no other person has received this five-star general title from the Turkish Republic.

Stalemate (September 1921 – August 1922)[]

Having failed to reach a military solution, Greece appealed to the Allies for help, but early in 1922 Britain, France and Italy decided that the Treaty of Sèvres could not be enforced and had to be revised. In accordance with this decision, under successive treaties, the Italian and French troops evacuated their positions, leaving the Greeks exposed.

In March 1922, the Allies proposed an armistice. Feeling that he now held the strategic advantage, Mustafa Kemal declined any settlement while the Greeks remained in Anatolia and intensified his efforts to re-organise the Turkish military for the final offensive against the Greeks. At the same time, the Greeks strengthened their defensive positions, but were increasingly demoralised by the inactivity of remaining on the defensive and the prolongation of the war. The Greek government was desperate to get some military support by the British or at least secure a loan, so it developed an ill-thought plan to force the British diplomatically, by threatening their positions in Constantinople, but this never materialised. The occupation of Constantinople would have been an easy task at this time because the Allied troops garrisoned there were much fewer than the Greek forces in Thrace (two divisions). The end result though was instead to weaken the Greek defences in Smyrna by withdrawing troops. The Turkish forces, on the other hand, were recipients of significant assistance from Soviet Russia. On 29 April, the Soviet authorities supplied the Turkish consul critical quantities of arms and ammunition, sufficient for three Turkish divisions. On 3 May, the Soviet government handed over 33,500,000 gold rubles to Turkey—the balance of the credit of 10,000,000 gold rubles.[62]

Voices in Greece increasingly called for withdrawal, and demoralizing propaganda spread among the troops. Some of the removed Venizelist officers organised a movement of "National Defense" and planned a coup to secede from Athens, but never gained Venizelos's endorsement and all their actions remained fruitless.

Historian Malcolm Yapp wrote that:[63]

After the failure of the March negotiations the obvious course of action for the Greeks was to withdraw to defensible lines around Izmir but at this point fantasy began to direct Greek policy, the Greeks stayed in their positions and planned a seizure of Constantinople, although this latter project was abandoned in July in the face of Allied opposition.

Turkish counter-attack[]

Dumlupınar[]

The Turks finally launched a counter-attack on August 26, what has come to be known to the Turks as the "Great Offensive" (Büyük Taarruz). The major Greek defense positions were overrun on August 26, and Afyon fell next day. On August 30, the Greek army was defeated decisively at the Battle of Dumlupınar, with many of its soldiers captured or slain and a large part of its equipment lost.[64] This date is celebrated as Victory Day, a national holiday in Turkey and salvage day of Kütahya. During the battle, the Greek generals Nikolaos Trikoupis and Kimon Digenis were captured by the Turkish forces.[65] General Trikoupis learned only after his capture that he had been recently appointed Commander-in-Chief in General Hatzianestis' place. According to the Greek Army General Staff, major generals Nikolaos Trikoupis and Kimon Digenis surrendered on 30 August 1922 by the village of Karaja Hissar due to lack of ammunitions, food and supplies[66] On September 1, Mustafa Kemal issued his famous order to the Turkish army: "Armies, your first goal is the Mediterranean, Forward!"[64]

Turkish advance on Smyrna[]

On September 2, Eskişehir was captured and the Greek government asked Britain to arrange a truce that would at least preserve its rule in Smyrna. However Kemal Mustafa Atatürk had categorically refused to acknowledge even a temporary Greek occupation of Smyrna, calling it a foreign occupation, and pursued an aggressive military policy instead.[67] Balıkesir and Bilecik were taken on September 6, and Aydın the next day. Manisa was taken on September 8. The government in Athens resigned. Turkish cavalry entered Smyrna on September 9. Gemlik and Mudanya fell on September 11, with an entire Greek division surrendering. The expulsion of the Greek Army from Anatolia was completed on September 18. As historian George Lenczowski has put it: "Once started, the offensive was a dazzling success. Within two weeks the Turks drove the Greek army back to the Mediterranean Sea."[68]

Entry of the Turkish army commanded by Mustafa Kemal Pasha to Smyrna (Izmir) on September 9, 1922

Hanging of the Turkish flag at the seat of the Governor of Izmir on September 9, 1922

Commander-in-chief Mushir Mustafa Kemal Pasha arrives in Izmir with Mushir Fevzi Pasha and Aide-de-camp Major Salih Bey on September 10, 1922.

Mirliva Fahrettin Pasha on his first visit to Izmir

The vanguards of Turkish cavalry entered the outskirts of Smyrna on September 8. On the same day, the Greek headquarters had evacuated the town. The Turkish cavalry rode into the town around eleven o'clock on the Saturday morning of September 9.[69][70] On September 10, with the possibility of social disorder, Mustafa Kemal was quick to issue a proclamation, sentencing to death any Turkish soldier who harmed non-combatants.[71] A few days before the Turkish capture of the city, Mustafa Kemal's messengers distributed leaflets with this order written in Greek. Mustafa Kemal said that the Ankara government would not be held responsible for any occurrence of a massacre.[72]

Atrocities were committed against Greek and Armenian populaces, and their properties were pillaged. Most of the eye-witness reports identified troops from the Turkish army having set the fire in the city.[73][74] The Greek and Armenian quarters of the city were burned, the Turkish as well as Jewish quarters stood.[75]

Chanak Crisis[]

After re-capturing Smyrna, Turkish forces headed north for the Bosporus, the sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles where the Allied garrisons were reinforced by British, French and Italian troops from Constantinople.[67] In an interview published in the Daily Mail, September 15, Mustafa Kemal stated that: "Our demands remain the same after our recent victory as they were before. We ask for Asia Minor, Thrace up to the river Maritsa and Constantinople... We must have our capital and I should in that case be obliged to march on Constantinople with my army, which will be an affair of only a few days. I must prefer to obtain possession by negotiation though, naturally I cannot wait indefinitely."[76]

Around this time, several Turkish officers were sent to infiltrate secretly into Constantinople to help organize Turkish population living in the city in the event of a war. For instance, Ernest Hemingway, who was at the time a war correspondent for the newspaper Toronto Star, reported that:[77]

"Another night a [British] destroyer... stopped a boatload of Turkish women who were crossing from Asia Minor...On being searched for arms it turned out all the women were men. They were all armed and later proved to be Kemalist officers sent over to organize the Turkish population in the suburbs in case of an attack on Constantinople"

The British cabinet initially decided to resist the Turks if necessary at the Dardanelles and to ask for French and Italian help to enable the Greeks to remain in eastern Thrace.[78] The British government also issued a request for military support from its colonies. The response from the colonies was negative (with the exception of New Zealand). Furthermore, Italian and French forces abandoned their positions at the straits and left the British alone to face the Turks. On September 24, Mustafa Kemal's troops moved into the straits zones and refused British requests to leave. The British cabinet was divided on the matter but eventually any possible armed conflict was prevented. British General Charles Harington, allied commander in Constantinople, kept his men from firing on Turks and warned the British cabinet against any rash adventure. The Greek fleet left Constantinople upon his request. The British finally decided to force the Greeks to withdraw behind the Maritsa in Thrace. This convinced Mustafa Kemal to accept the opening of armistice talks.

Resolution[]

The Armistice of Mudanya was concluded on October 11, 1922. The Allies (Britain, France and Italy) retained control of eastern Thrace and the Bosporus. The Greeks were to evacuate these areas. The agreement came into force starting October 15, 1922, one day after the Greek side agreed to sign it.

The Armistice of Mudanya was followed by the Treaty of Lausanne. Separate from this treaty, Turkey and Greece came to an agreement covering an exchange of populations. Over one million Greek Orthodox Christians were displaced; most of them were resettled in Attica and the newly incorporated Greek territories of Macedonia and Thrace and were exchanged with about 500,000 Muslims displaced from Greek territories.

Factors contributing to the outcome[]

The Greeks estimated, despite warnings from the French and British not to underestimate the enemy, that they would need only three months to defeat the already weakened Turks on their own.[79] Exhausted from four years of bloodshed, no Allied power had the will to engage in a new war and relied on Greece. During the Conference of London in February 1921, the Greek prime minister Kalogeropoulos revealed that the morale of the Greek army was excellent and their courage was undoubted, he added that in his eyes the Kemalists were "not regular soldiers; they merely constituted a rabble worthy of little or no consideration".[80] Still, the Allies had doubts about Greek military capacity to advance in Anatolia, facing vast territories, long lines of communication, financial shortcomings of the Greek treasury and above all the toughness of the Turkish peasant/soldier.[81][82] After the Greek failure to rout and defeat the new established Turkish army in the First and Second Battle of İnönü the Italians began to evacuate their occupation zone in southwestern Anatolia in July 1921. Furthermore, the Italians also claimed that Greece had violated the limits of the Greek occupation laid down by the Council of Four.[82] France, on the other hand, had its own front in Cilicia with the Turkish nationalists. The French, like the other Allied powers, had changed their support to the Turks in order to build a strong buffer state against the Bolsheviks and were looking to leave.[83] After the Greeks had failed again to knock out the Turks in the decisive Battle of Sakarya, the French finally signed the Treaty of Ankara (1921) with the Turks in late October 1921. In addition, the Allies did not fully allow the Greek Navy to effect a blockade of the Black Sea coast, which could have restricted Turkish imports of food and material. Still, the Greek Navy bombarded some larger ports (June and July 1921 Inebolu; July 1921 Trabzon, Sinop; August 1921 Rize, Trabzon; September 1921 Araklı, Terme, Trabzon; October 1921 Izmit; June 1922 Samsun).[84] The Greek Navy was able to blockade the Black Sea coast especially before and during the First and Second İnönü, Kütahya–Eskişehir and Sakarya battles, preventing weapon and ammunition shipments.[85]

Having adequate supplies was a constant problem for the Greek Army. Although it was not lacking in men, courage or enthusiasm, it was soon lacking in nearly everything else. Due to her poor economy, Greece could not sustain long-term mobilisation. According to a British report from May 1922, 60,000 Anatolian native Greeks, Armenians and Circassians served under arms in the Greek occupation (of this number, 6,000–10,000 were Circassians).[86] In comparison, the Turks had also difficulties to find enough fit men, as a result of 1.5 million military casualties during World War I.[87] Very soon, the Greek Army exceeded the limits of its logistical structure and had no way of retaining such a large territory under constant attack by initially irregular and later regular Turkish troops. The idea that such large force could sustain offensive by mainly "living off the land" proved wrong. Although the Greek Army had to retain a large territory after September 1921, the Greek Army was more motorized than the Turkish Army.[88] The Greek Army had in addition to 63,000 animals for transportation, 4,036 trucks and 1,776 automobiles/ambulances,[88](according to the Greek Army History Directorate total number of trucks, including ambulances, was 2500). Only 840 of them have been used for the advance to Angora, also 1.600 camels and a great number of ox and horse carts,[89] whereas the Turkish Army relied on transportation with animals. They had 67,000 animals (of whom were used as: 3,141 horse carts, 1,970 ox carts, 2,318 tumbrels and 71 phaetons), but only 198 trucks and 33 automobiles/ambulances.[88]

As the supply situation worsened for the Greeks, things improved for the Turks.[citation needed] After the Armistice of Mudros, the Allies had dissolved the Ottoman army, confiscated all Ottoman weapons and ammunition,[90] hence the Turkish National Movement which was in the progress of establishing a new army, was in desperate need of weapons. In addition to the weapons not yet confiscated by the Allies,[91] they enjoyed Soviet support from abroad, in return for giving Batum to the Soviet Union. The Soviets also provided monetary aid to the Turkish National Movement, not to the extent that they promised but almost in sufficient amount to make up the large deficiencies in the promised supply of arms.[1] One of the main reasons for Soviet support was that Allied forces were fighting on Russian soil against the Bolshevik regime, therefore the Turkish opposition was much favored by Moscow.[1] The Italians were embittered from their loss of the Smyrna mandate to the Greeks, and they used their base in Antalya to arm and train Turkish troops to assist the Kemalists against the Greeks.[92][page needed]

A British military attaché, who inspected the Greek Army in June 1921, was quoted as saying, "more efficient fighting machine than I have ever seen it."[93] Later he wrote: "The Greek Army of Asia Minor, which now stood ready and eager to advance, was the most formidable force the nation had ever put into field. Its morale was high. Judged by Balkan standards, its staff was capable, its discipline and organization good."[94] Turkish troops had a determined and competent strategic and tactical command, manned by World War I veterans. The Turkish army enjoyed the advantage of being in defence, executed in the new form of 'area defence'.

Mustafa Kemal presented himself as revolutionary to the communists, protector of tradition and order to the conservatives, patriot soldier to the nationalists, and a Muslim leader for the religious, so he was able to recruit all Turkish elements and motivate them to fight. The Turkish National Movement attracted sympathizers especially from the Muslims of the far east countries.[95] The Khilafet Committee in Bombay started a fund to help the Turkish National struggle and sent both financial aid and constant letters of encouragement. Not all of the money arrived, and Mustafa Kemal decided not use the money that was sent by the Khilafet Committee. The money was restored in the Ottoman Bank. After the war, it was later used for the founding of the Türkiye İş Bankası.[96]

Atrocities and ethnic cleansing by both sides[]

Turkish genocides of Greeks and Armenians[]

Rudolph J. Rummel estimated that from 1900 to 1923, various Turkish regimes killed from 3,500,000 to over 4,300,000 Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians.[97][98] Rummel estimates that 440,000 Armenian civilians and 264,000 Greek civilians were killed by Turkish forces during the Turkish War of Independence between 1919 and 1922.[99] However, he also gives the figures in his study of between 1.428 to 4.388 million dead of whom 2.781 millions were Armenian, Greek, Nestorians, Turks, Circassians and others, in line 488. British historian and journalist Arnold J. Toynbee stated that when he toured the region[where?] he saw numerous Greek villages that had been burned to the ground. Toynbee also stated that the Turkish troops had clearly, individually and deliberately, burned down each house in these villages, pouring petrol on them and taking care to ensure that they were totally destroyed.[100] There were massacres throughout 1920–23, the period of the Turkish War of Independence, especially of Armenians in the East and the South, and against the Greeks in the Black Sea Region.[101]

Sivas province governor Ebubekir Hâzım Tepeyran said in 1919 that the massacres were so horrible that he could not bear to report them. He referred to the atrocities committed against Greeks in the Black Sea region, and according to the official tally 11,181 Greeks were murdered in 1921 by the Central Army under the command of Nurettin Pasha (who is infamous for the killing of Archbishop Chrysostomos). Some parliamentary deputies demanded that Nurettin Pasha be sentenced to death and it was decided to put him on trial, although the trial was later revoked by the intervention of Mustafa Kemal. Taner Akçam wrote that according to one newspaper, Nurettin Pasha had proposed the killing of all the remaining Greek and Armenian populations in Anatolia, a suggestion rejected by Mustafa Kemal.[102] These sentiments mainly arose from the desire for vengeance following the ethnic cleansings committed by Greek Army systematically throughout the failed campaign.[citation needed]

There were also several contemporary Western newspaper articles reporting the atrocities committed by Turkish forces against Christian populations living in Anatolia, mainly Greek and Armenian civilians.[103][104][105][106][107][108] For instance, according to the London Times, "The Turkish authorities frankly state it is their deliberate intention to let all the Greeks die, and their actions support their statement."[103] An Irish paper, the Belfast News Letter wrote, "The appalling tale of barbarity and cruelty now being practiced by the Angora Turks is part of a systematic policy of extermination of Christian minorities in Asia Minor."[108] According to the Christian Science Monitor, the Turks felt that they needed to murder their Christian minorities due to Christian superiority in terms of industriousness and the consequent Turkish feelings of jealousy and inferiority. The paper wrote: "The result has been to breed feelings of alarm and jealousy in the minds of the Turks, which in later years have driven them to depression. They believe that they cannot compete with their Christian subjects in the arts of peace and that the Christians and Greeks especially are too industrious and too well educated as rivals. Therefore, from time to time they have striven to try and redress the balance by expulsion and massacre. That has been the position generations past in Turkey again if the Great powers are callous and unwise enough to attempt to perpetuate Turkish misrule over Christians."[109] According to the newspaper the Scotsman, on August 18 of 1920, in the Feival district of Karamusal, South-East of Ismid in Asia Minor, the Turks massacred 5,000 Christians.[104] There were also massacres during this period against Armenians, continuing the policies of the 1915 Armenian Genocide according to some Western newspapers.[110] On February 25, 1922, 24 Greek villages in the Pontus region were burnt to the ground. An American newspaper, the Atlanta Observer wrote: "The smell of the burning bodies of women and children in Pontus" said the message "comes as a warning of what is awaiting the Christian in Asia Minor after the withdrawal of the Hellenic army."[105] In the first few months of 1922, 10,000 Greeks were killed by advancing Kemalist forces, according to Belfast News Letter.[103][108] According to the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin the Turks continued the practice of slavery, seizing women and children for their harems and raping numerous women.[103][108][111] The Christian Science Monitor wrote that Turkish authorities also prevented missionaries and humanitarian aid groups from assisting Greek civilians who had their homes burned, the Turkish authorities leaving these people to die despite abundant aid. The Christian Science Monitor wrote: "the Turks are trying to exterminate the Greek population with more vigor than they exercised towards the Armenians in 1915."[106]

Atrocities against Pontic Greeks living in the Pontus region is recognized in Greece and Cyprus[112] as the Pontian Genocide. According to a proclamation made in 2002 by the then-governor of New York (where a sizeable population of Greek Americans resides), George Pataki, the Greeks of Asia Minor endured immeasurable cruelty during a Turkish government-sanctioned systematic campaign to displace them; destroying Greek towns and villages and slaughtering additional hundreds of thousands of civilians in areas where Greeks composed a majority, as on the Black Sea coast, Pontus, and areas around Smyrna; those who survived were exiled from Turkey and today they and their descendants live throughout the Greek diaspora.[113]

By 9 September 1922, the Turkish army had entered Smyrna, with the Greek authorities having left two days before. Large scale disorder followed, with the Christian population suffering under attacks from soldiers and Turkish inhabitants. The Greek archbishop Chrysostomos had been lynched by a mob which included Turkish soldiers, and on September 13, a fire from the Armenian quarter of the city had engulfed the Christian waterfront of the city, leaving the city devastated. The responsibility for the fire is a controversial issue; some sources blame Turks, and some sources blame Greeks or Armenians. Some 50,000[114] to 100,000[115] Greeks and Armenians were killed in the fire and accompanying massacres.

Greek massacres of Turks[]

British historian Arnold J. Toynbee wrote that there were organized atrocities following the Greek landing at Smyrna on 15 May 1919. He also stated that he and his wife were witnesses to the atrocities perpetrated by Greeks in the Yalova, Gemlik, and Izmit areas and they not only obtained abundant material evidence in the shape of "burnt and plundered houses, recent corpses, and terror stricken survivors" but also witnessed robbery by Greek civilians and arson by Greek soldiers in uniform as they were being perpetrated.[116] Toynbee wrote that as soon as the Greek Army landed, they started committing atrocities against Turkish civilians, as they "laid waste the fertile Maeander (Meander) Valley", and forced thousands of Turks to take refuge outside the borders of the areas controlled by the Greeks.[117] Secretary of State for the Colonies and later Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill comparing the specific activities with the genocide policies perpetrated by the Turkish side noted that the Greek atrocities were on "a minor scale" compared to the "appalling deportations of Greeks from the Trebizond and Samsun district."[118]

During the Battle of Bergama, the Greek army committed a massacre against Turkish civilians in Menemen killing 200 and injuring 200 people.[119] Some Turkish sources claim that the death count of the Menemen massacre was 1000.[120][119] On 24 June 1921, a massacre occurred in İzmit killing more than 300 Turkish civilians according to Arnold J. Toynbee.[121]

Harold Armstrong, a British officer who was a member of the Inter-Allied Commission, reported that as the Greeks pushed out from Smyrna, they massacred and raped civilians, and burned and pillaged as they went.[122] Johannes Kolmodin was a Swedish orientalist in Smyrna. He wrote in his letters that the Greek army had burned 250 Turkish villages.[123] In one village the Greek army demanded 500 gold liras to spare the town; however, after payment, the village was still sacked.[124]

The Inter-Allied commission, consisting of British, French, American and Italian officers,[d] and the representative of the Geneva International Red Cross, M. Gehri, prepared two separate collaborative reports on their investigations of the Gemlik-Yalova Peninsula Massacres. These reports found that Greek forces committed systematic atrocities against the Turkish inhabitants.[125] And the commissioners mentioned the "burning and looting of Turkish villages", the "explosion of violence of Greeks and Armenians against the Turks", and "a systematic plan of destruction and extinction of the Moslem population".[126] In their report of the 23rd May 1921, the Inter-Allied commission stated also that "This plan is being carried out by Greek and Armenian bands, which appear to operate under Greek instructions and sometimes even with the assistance of detachments of regular troops".[127] The Inter-Allied commission also stated that the destruction of villages and the disappearance of the Muslim population might have as its objective to create in this region a political situation favourable to the Greek Government.[127] The Allied investigation also pointed that the specific events were reprisals for the general Turkish oppression of the past years and especially for the Turkish atrocities committed in the Marmara region one year before when several Greek villages had been burned and thousands of Greeks massacred.[128]

Arnold J. Toynbee wrote that they obtained convincing evidence that similar atrocities had been started in wide areas all over the remainder of the Greek-occupied territories since June 1921.[116] He argued that "the situation of the Turks in Smyrna City had become what could be called without exaggeration a 'reign of terror', it was to be inferred that their treatment in the country districts had grown worse in proportion."[129] However, Toynbee omits to notice that the Allied report concluded that the Ismid peninsula atrocities committed by the Turks "have been considerable and more ferocious than those on the part of the Greeks".[118] In general, as reported by a British intelligence report: "the [Turkish] inhabitants of the occupied zone have in most cases accepted the advent of Greek rule without demur and in some cases undoubtedly prefer it to the [Turkish] Nationalist regime which seems to have been founded on terrorism". British military personnel observed that the Greek army near Uşak was warmly welcomed by the Muslim population for "being freed from the license and oppression of the [Turkish] Nationalist troops"; there were "occasional cases of misconduct" by the Greek troops against the Muslim population, and the perpetrators were prosecuted by the Greek authorities, while the "worst miscreants" were "a handful of Armenians recruited by the Greek army", who were then sent back to Constantinople.[130] Justin McCarthy reports that during the negotiations for the Treaty of Lausanne, the chief negotiator of the Turkish delegation, Ismet Pasha (İnönü), gave an estimate of 1.5 million Anatolian Turks that had been exiled or died in the area of Greek occupation. Of these, McCarthy estimates that 860,000 refuged and 640,000 died; with many, if not most of those who died, being refugees as well. The comparison of census figures shows that 1,246,068 Anatolian Muslims had become refugees or had died.[131][132] However, McCarthy's work has faced harsh criticism by scholars who have characterized McCarthy's views as indefensibly biased towards Turkey and the Turkish official position[133] as well as engaging in genocide denial.[134][135][136] As part of the Lausanne Treaty, Greece recognized the obligation to make reparations for damages caused in Anatolia, though Turkey agreed to renounce all such claims due to Greece's difficult financial situation.[137]

Greek scorched-earth policy[]

According to a number of sources, the retreating Greek army carried out a scorched-earth policy while fleeing from Anatolia during the final phase of the war.[139] Historian of the Middle East, Sydney Nettleton Fisher wrote that: "The Greek army in retreat pursued a burned-earth policy and committed every known outrage against defenceless Turkish villagers in its path."[139] Norman M. Naimark noted that "the Greek retreat was even more devastating for the local population than the occupation".[140]

James Loder Park, the U.S. Vice-Consul in Constantinople at the time, toured much of the devastated area immediately after the Greek evacuation, and reported the situation in the surrounding cities and towns of İzmir he has seen, such as the Fire of Manisa.[141]

Kinross wrote, "Already most of the towns in its path were in ruins. One third of Ushak no longer existed. Alashehir was no more than a dark scorched cavity, defacing the hillside. Village after village had been reduced to an ash-heap. Out of the eighteen thousand buildings in the historic holy city of Manisa, only five hundred remained."[142]

In one of the examples of the Greek atrocities during the retreat, on 14 February 1922, in the Turkish village of Karatepe in Aydın Vilayeti, after being surrounded by the Greeks, all the inhabitants were put into the mosque, then the mosque was burned. The few who escaped fire were shot.[143] The Italian consul, M. Miazzi, reported that he had just visited a Turkish village, where Greeks had slaughtered some sixty women and children. This report was then corroborated by Captain Kocher, the French consul.[144]

Population Exchange[]

According to the population exchange treaty signed by both the Turkish and Greek governments, Greek orthodox citizens of Turkey and Turkish and Greek Muslim citizens residing in Greece were subjected to the population exchange between these two countries. Approximately 1,500,000 Orthodox Christians, being ethnic Greeks and ethnic Turks from Turkey and about 500,000 Turks and Greek Muslims from Greece were uprooted from their homelands.[145] M. Norman Naimark claimed that this treaty was the last part of an ethnic cleansing campaign to create an ethnically pure homeland for the Turks[146] Historian Dinah Shelton similarly wrote that "the Lausanne Treaty completed the forcible transfer of the country's Greeks."[147]

A large part of the Greek population was forced to leave their ancestral homelands of Ionia, Pontus and Eastern Thrace between 1914–22. These refugees, as well as Greek Americans with origins in Anatolia, were not allowed to return to their homelands after the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne.

See also[]

- List of massacres during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22)

- Chronology of the Turkish War of Independence

- Occupation of Smyrna

- Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

- Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor

- Asia Minor Defense Organization

Notes[]

- ^ The Turks fought only with irregular units (Kuva-yi Milliye) in the years 1919 and 1920. The Turks established their regular army towards the end of 1920. The First Battle of İnönü was the first battle where regular army units fought against the Greek army.

- ^ One Greek division had at least 25% more men than a Turkish division. In 1922, Turkish divisions had 7,000–8,000 men averagely, whereas Greek divisions had well over 10,000 men per division.

- ^ It is known as the Western Front (Known as Turkish: Batı Cephesi, Ottoman Turkish: گرب جابهاسی, romanized: Garb Cebhesi)[25] in Turkey, and Asia Minor Campaign (Greek: Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία, romanized: Mikrasiatikí Ekstrateía) or the Asia Minor Catastrophe (Greek: Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή, romanized: Mikrasiatikí Katastrofí) in Greece. Also referred to as Greek invasion of Anatolia[26]

- ^ General Hare, the British Delegate; General Bunoust, the French Delegate; General Dall'Olio, the Italian Delegate; Admiral Bristol, the American Delegate

References[]

- ^ a b c Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth century. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-27459-3.

- ^ "Why revolutionary Russia backed Turkish nationalists over communists". The Conversation. 28 November 2017.

- ^ The Place of the Turkish Independence War in the American Press (1918-1923) by Bülent Bilmez: "... the occupation of western Turkey by the Greek armies under the control of the Allied Powers, the discord among them was evident and publicly known. As the Italians were against this occupation from the beginning, and started 'secretly' helping the Kemalists, this conflict among the Allied Powers, and the Italian support for the Kemalists were reported regularly by the American press."

- ^ According to John R. Ferris, "Decisive Turkish victory in Anatolia ... produced Britain's gravest strategic crisis between the 1918 Armistice and Munich, plus a seismic shift in British politics ..." Erik Goldstein and Brian McKerche, Power and Stability: British Foreign Policy, 1865–1965, 2004 p. 139

- ^ A. Strahan claimed that: "The internationalisation of Constantinople and the Straits under the aegis of the League of Nations, feasible in 1919, was out of the question after the complete and decisive Turkish victory over the Greeks". A. Strahan, Contemporary Review, 1922.

- ^ N. B. Criss, Istanbul Under Allied Occupation, 1918–1923, 1999, p. 143. "In 1922, after the decisive Turkish victory over the Greeks, 40,000 troops moved towards Gallipoli."

- ^ It was composed (as of 1922) of around 2,500 ethnic Armenian volunteers. See Ramazian, Samvel (2010). Ιστορία των αρμενο-ελληνικών στρατιωτικών σχέσεων και συνεργασίας / Հայ-հունական ռազմական առնչությունների եւ համագործակցության պատմություն [History of Armenian-Greek military relations and cooperation] (in Greek and Armenian). Athens: Stamoulis Publications. pp. 200–1, 208–9. ISBN 9789609952002. Cited in Vardanyan, Gevorg. Հայ-հունական համագործակցության փորձերը Հայոց ցեղասպանության տարիներին (1915–1923 թթ.) [The attempts of the Greek-Armenian Co-operation during the Armenian Genocide (1915–1923)]]. akunq.net (in Armenian). Research Center on Western Armenian Studies. Archived from the original on 25 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Ergün Aybars, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti tarihi I, Ege Üniversitesi Basımevi, 1984, pg 319-334 (in Turkish)

- ^ Turkish General Staff, Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi, Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225

- ^ a b c d e Görgülü, İsmet (1992), Büyük Taarruz: 70 nci yıl armağanı (in Turkish), Genelkurmay basımevi, pp. 1, 4, 10, 360.

- ^ a b Erikan, Celâl (1917). 100 [i.e. Yüz] soruda Kurtuluş Savaşımızın tarihi. Gerçek Yayınevi.

- ^ a b Tuğlacı, Pars (1987), Çağdaş Türkiye (in Turkish), Cem Yayınevi, p. 169.

- ^ Eleftheria, Daleziou (2002). "Britain and the Greek-Turkish War and Settlement of 1919-1923: the Pursuit of Security by "Proxy" in Western Asia Minor". University of Glasgow. p. 108. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi [The Western Front in the Turkish War of Independence] (in Turkish), 2 (II ed.), Ankara: Turkish General Staff, 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Asian Review. East & West. 1934.

- ^ Sandler, Stanley (2002). Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-344-5.

- ^ History of the Campaign of Minor Asia, General Staff of Army, Athens: Directorate of Army History, 1967, p. 140,

on June 11 (OC) 6,159 officers, 193,994 soldiers (=200,153 men)

. - ^ Eleftheria, Daleziou (2002). "Britain and the Greek-Turkish War and Settlement of 1919-1923: the Pursuit of Security by "Proxy" in Western Asia Minor". University of Glasgow. p. 243. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Giritli, İsmet (November 1986), Samsun'da Başlayan ve İzmir'de Biten Yolculuk (1919–1922) (III ed.), Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi [Atatürk Research Center], archived from the original on 2013-04-05

- ^ a b c Sabahattin Selek: Millî mücadele - Cilt I (engl.: National Struggle - Edition I), Burçak yayınevi, 1963, page 109 (in Turkish)

- ^ Taşkıran, Cemalettin (2005). "Kanlı mürekkeple yazın çektiklerimizi ... !": Milli Mücadelede Türk ve Yunan esirleri, 1919–1923. p. 26. ISBN 978-975-8163-67-0.

- ^ Επίτομος Ιστορία Εκστρατείας Μικράς Ασίας 1919–1922 [Abridged History of the Campaign of Minor Asia] (in Greek), Athens: Directorate of Army History, 1967, Table 2.

- ^ a b Στρατιωτική Ιστορία journal, Issue 203, December 2013, page 67

- ^ Ahmet Özdemir, Savaş esirlerinin Milli mücadeledeki yeri, Ankara University, Türk İnkılap Tarihi Enstitüsü Atatürk Yolu Dergisi, Edition 2, Number 6, 1990, pp. 328–332

- ^ [1] Harp Mecmuası

- ^ Kate Fleet, I. Metin Kunt, Reşat Kasaba, Suraiya Faroqhi (2008). The Cambridge History of Turkey. p. 226.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Sowards, Steven W (2004-05-07). "Greek nationalism, the 'Megale Idea' and Venizelism to 1923". Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History (The Balkans in the Age of Nationalism). MSU. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ^ Woodhouse, C.M. The Story of Modern Greece, Faber and Faber, London, 1968, p. 204

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold J; Kirkwood, Kenneth P (1926), Turkey, London: Ernest Benn, p. 94.

- ^ Giles Milton, Paradise Lost, 2008, Sceptre, ISBN 978-0-340-83786-3

- ^ Tung, Anthony (2001). "The City the Gods Besieged". Preserving the World's Great Cities: The Destruction and Renewal of the Historic Metropolis. New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-609-80815-X, the same source depicts a table with Athens having a population of 123,000 in 1896

- ^ Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and Its Impact on Greece. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6

- ^ Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and Its Impact on Greece. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6.

- ^ Roberts, Thomas Duval. Area Handbook for the Republic of Turkey. p. 79

- ^ a b Lowe & Dockrill 2002, p. 367.

- ^ Zamir, Meir (1981). "Population Statistics of the Ottoman Empire in 1914 and 1919". Middle Eastern Studies. 7 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1080/00263208108700459. JSTOR 4282818.

- ^ Montgomery, AE (1972). "The Making of the Treaty of Sèvres of 10 August 1920". The Historical Journal. 15 (4): 775. doi:10.1017/S0018246X0000354X.

- ^ "Not War Against Islam – Statement by Greek Prime Minister", The Scotsman, p. 5, June 29, 1920.

- ^ Smith 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Toynbee 1922, pp. 312–13.

- ^ a b Smith 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Kinross 1960, p. 154.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 342.

- ^ Ansiklopedisi 1982, pp. 4273–74.

- ^ K. E. Fleming (2010). Greece--a Jewish History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14612-6.

- ^ Ραμαζιάν Σ., Ιστορία τών Άρμενο – Έλληνικών στρατιωτικών σχεσεων καί συνεργασίας, Αθήνα, 2010. Ռամազյան Ս., Հայ-հունական ռազմական առնչությունների և համագործակցության պատմություն, Աթենք, 2010, pp. 200–201, 208-209; see The attempts of the Greek-Armenian Co-operation during the Armenian Genocide (1915–1923) by Gevorg Vardanyan

- ^ The Ruined City of Smyrna: Giles Milton's 'Paradise Lost', NY Sun,

... on May 15, 1919, Greek troops disembarked in the city's harbor to take possession of their prize. It was a scene of rejoicing and revenge, dramatically evoked by Mr. Milton. The local Greeks, who had long nurtured a grievance against the Ottoman state and had been severely persecuted during the war, welcomed the Greek army as liberators.

- ^ Sunga, Lyal S. (1992-01-01). Individual Responsibility in International Law for Serious Human Rights Violations. Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-0-7923-1453-0.

- ^ Bernhardsson, Magnus (2005-12-20). Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology and Nation Building in Modern Iraq. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70947-8.

- ^ Treaty of Lausanne, GR: MFA, 24 July 1923, archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

- ^ Kinross 1960, p. 233.

- ^ "Venizelos and the Asia Minor Catastrophe". A history of Greece. Retrieved 2008-09-03.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Stone, David R., "Soviet Arms Exports in the 1920s," 'Journal of Contemporary History,' 2013, Vol.48(1), pp.57-77

- ^ Dobkin 1998, pp. 60–1, 88–94.

- ^ Kapur, H, Soviet Russia and Asia, 1917–1927.

- ^ Шеремет, В (1995), Босфор (in Russian), Moscow, p. 241.

- ^ Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn. Moscow, 1963, No. 11, p. 148.

- ^ Kinross 1960, p. 275.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 360.

- ^ Greek Army General Staff, The Minor Asia Campagne, volume 5th, The Angora Campagne, Athens, 1986

- ^ Kinross 1960, p. 277.

- ^ Kapur, H. Soviet Russia and Asia, 1917–1927, p. 114.

- ^ Yapp, Malcolm E. The Making of the Modern Near East, 1792–1923, London; New York: Longman, 1987, p. 319, ISBN 978-0-582-49380-3

- ^ a b Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 362.

- ^ Kinross 1960, p. 315.

- ^ Greek Army History Directorate: The Minor Asia Campaign, volume 7,retreat of I and II Army Korps, page 259

- ^ a b Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 363.

- ^ Lenczowski, George. The Middle East in World Affairs, Cornell University Press, New York, 1962, p. 107.

- ^ Papoutsy, Christos (2008), Ships of Mercy: the True Story of the Rescue of the Greeks, Smyrna, September 1922, Peter E Randall, p. 16, ISBN 978-1-931807-66-1.

- ^ Murat, John (1999), The Great Extirpation of Hellenism and Christianity in Asia Minor: The Historic and Systematic Deception of World Opinion Concerning the Hideous Christianity's Uprooting of 1922, p. 132, ISBN 978-0-9600356-7-0.

- ^ Glenny, Misha (2000), The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804–1999 (hardcover) (May 1, 2000 ed.), Viking, ISBN 978-0-670-85338-0[page needed]

- ^ James, Edwin L. "Kemal Won't Insure Against Massacres," New York Times, September 11, 1922.

- ^ Horton, George. "The Blight of Asia". Bobbs-Merril Co. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ Dobkin 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Stewart, Matthew (2003-01-01). "It Was All a Pleasant Business: The Historical Context of "On the Quai at Smyrna"". The Hemingway Review. 23 (1): 58–71. doi:10.1353/hem.2004.0014. S2CID 153449331.

- ^ ELEFTHERIA DALEZIOU, BRITAIN AND THE GREEK-TURKISH WAR AND SETTLEMENT OF 1919-1923: THE PURSUIT OF SECURITY BY 'PROXY' IN WESTERN ASIA MINOR

- ^ Ernest Hemingway, Hemingway on War, p 278 Simon and Schuster, 2012 ISBN 1476716048,

- ^ Walder, David (1969). The Chanak Affair, London, p. 281.

- ^ Friedman 2012, pp. 238, 248.

- ^ Friedman 2012, p. 238.

- ^ Friedman 2012, p. 251.

- ^ a b Smith 1999, p. 108.

- ^ Payaslian, Simon (2007), The History of Armenia, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 163, ISBN 978-1-4039-7467-9

- ^ Şemsettin Bargut; Turkey. Deniz Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı (2000). 1. Dünya Harbi'nde ve Kurtuluş Savaş'ında Türk deniz harekatı. Dz.K.K. Merkez Daire Başkanlığı Basımevi. ISBN 978-975-409-165-6.

- ^ Doğanay, Rahmi (2001). Millı̂ Mücadele'de Karadeniz, 1919–1922. Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi. ISBN 978-975-16-1524-4.

- ^ Gingeras, Ryan (2009), Sorrowful Shores:Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1912–1923, Oxford University Press, p. 225, ISBN 978-0-19-160979-4.

- ^ Erickson, Edward J, Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War, p. 211.

- ^ a b c "Turkish Great Offensive", NTV Tarih [NTV History Journal], NTV Yayınları (31): 45–55, August 2011.

- ^ Greek Army History Directorate, The Minor Asia Campaign Logistic and Transportation, Athens, 1965, page 63

- ^ Turan, Şerafettin (1991), Türk devrim tarihi. 2. kitap: ulusal direnisten, Türkiye, cumhuriyeti'ne (in Turkish), Bilgi Yayinevi, p. 157, ISBN 975-494-278-1.

- ^ Türkmen, Zekeriya (2001), Mütareke döneminde ordunun durumu ve yeniden yapılanması, 1918–1920, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Smith 1999.

- ^ Smith 1999, p. 207.

- ^ Smith 1999, p. 207.

- ^ Kinross 1960, p. 298.

- ^ Müderrisoğlu, Alptekin (1990), Kurtuluş Savaşının Mali Kaynakları (in Turkish), p. 52, ISBN 975-16-0269-6.

- ^ Turkey's Dead (1900–1023) (GIF) (table).

- ^ Rummel, Rudolph J. "Statistics Of Turkey's Democide Estimates, Calculations, And Sources", Statistics of Democide, 1997.

- ^ Rumel, Rudolph, Turkish Democide, Power Kills, Lines 363 & 382. University of Hawai'i.

- ^ Toynbee 1922, p. 152.

- ^ Akçam 2006, p. 322.

- ^ Akçam 2006, p. 323.

- ^ a b c d "Turk's Insane Savagery: 10,000 Greeks Dead." The Times. Friday, May 5, 1922.

- ^ a b "5,000 Christians Massacred, Turkish Nationalist Conspiracy", The Scotsman, August 24, 1920.

- ^ a b "24 Greek Villages are Given to the Fire." Atlanta Constitution. March 30, 1922

- ^ a b "Near East Relief Prevented from Helping Greeks", Christian Science Monitor, July 13, 1922.

- ^ "Turks will be Turks," The New York Times, Sep. 16, 1922

- ^ a b c d "More Turkish Atrocities", Belfast News Letter, May 16, 1922.

- ^ "Turkish Rule over Christian Peoples", Christian Science Monitor, Feb 1, 1919.

- ^ "Allies to Act at Once on Armenian Outrages," The New York Times, Feb. 29, 1920.

- ^ "Girls died to escape Turks" (PDF), The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, University of Michigan, 1919, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-03, retrieved 2013-04-01

- ^ , New York City: Cyprus Press Office Missing or empty

|title=(help). - ^ Pataki, George E (October 6, 2002), Governor Proclaims October 6th, 2002 as the 80th Anniversary of the Persecution of Greeks of Asia Minor (Resolution of the State), New York.

- ^ Freely, John (2004). The Western Shores of Turkey: Discovering the Aegean and Mediterranean Coasts. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-85043-618-8.

- ^ Horowitz, Irving Louis; Rummel, Rudolph J (1994). "Turkey's Genocidal Purges". Death by Government. Transaction Publishers. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-56000-927-6.

- ^ a b Toynbee 1922, p. 260.

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee and Kenneth P. Kirkwood, Turkey, 1926, London: Ernest Benn, p. 92.

- ^ a b Shenk, Robert (2017). America's Black Sea Fleet: The U.S. Navy Amidst War and Revolution, 1919 1923. Naval Institute Press. p. 36. ISBN 9781612513027.

- ^ a b Erhan, Çağrı, 1972- (2002). Greek occupation of Izmir and adjoining territories : report of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry (May - September 1919). OCLC 499949038.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Yalazan, Talat (1994). Türkiye'de vahset ve soy kırımı girisimi: (15 Mayıs 1919 - 9 Eylül 1922). 15 Mayıs 1919 - 13 Eylül 1921 (in Turkish). Genelkurmay Basımevi. ISBN 9789754090079.

- ^ Toynbee 1922.

- ^ Steven Béla Várdy; T. Hunt Tooley; Ágnes Huszár Várdy (2003). Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Social Science Monographs. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-88033-995-7.

- ^ Özdalga, Elizabeth. The Last Dragoman: the Swedish Orientalist Johannes Kolmodin as Scholar, Activist and Diplomat (2006), Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, p. 63

- ^ McCarthy, Justin (1995). Death and exile: the ethnic cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821–1922. Darwin Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-87850-094-9.

- ^ Toynbee 1922, p. 285: M. Gehri stated in his report that "... The Greek army of occupation have been employed in the extermination of the Muslim population of the Yalova-Gemlik peninsula."

- ^ Naimark 2002, p. 45.

- ^ a b Toynbee 1922, p. 284.

- ^ Shenk, Robert (2017). America's Black Sea Fleet: The U.S. Navy Amidst War and Revolution, 1919 1923. Naval Institute Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9781612513027.

- ^ Toynbee 1922, p. 318.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. p. 401. ISBN 9780674916456.

- ^ Travlos, Konstantinos (2021). "Appendix A: Casualties by Professor Konstantinos". The Turkish War of Independence a Military History, 1919-1923 by Edward J. Erickson. p. 352-353. ISBN 9781440878428.

When it comes to Muslims population loss, the best estimates are those of McCarthy, who argues for an estimated population loss of 1,246,068 Muslims between 1914 and 1922 in Anatolia, and arbitrarily ascribes 640,000 of those as occurring in the Greek and British zones of operation in 1919–1922.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin (1996). Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922. Darwin Press Incorporated. pp. 295–297, 303–304. ISBN 0-87850-094-4.

Of all the estimates of the number of Muslim refugees, the figures offered by İsmet Pașa (İnönü) at the Lausanne Peace Conference seem most accurate. He estimated that 1.5 million Anatolian Turks had been exiled or had died in the area of Greek occupation. This estimate may appear high, but it fits well with estimates made by contemporary European observers. Moreover, İsmet Pașa's figures on refugees were presented to the Conference accompanied by detailed statistics of destruction in the occupied region, and these statistics make the estimate seem probable. İsmet Pașa, quoting from a census made after the war, demonstrated that 160,739 buildings had been destroyed in the occupied region. The destroyed homes alone would account for many hundreds of thousands of refugees, and not all the homes of refugees were destroyed. European accounts of refugee numbers were necessarily fragmented, but when compiled they support İsmet Pașa's estimate. The British agent at Aydin, Blair Fish, reported 177,000 Turkish refugees in Aydin Vilâyeti by 30 September 1919, only four months after the Greek landing. The Italian High Commissioner at Istanbul accepted an Ottoman estimate that there were 457,000 refugees by September of 1920, and this figure did not include the new refugees in the fall and winter of 1920 to 1921. Dr. Nansen stated that 75,000 Turks had come to the Istanbul area alone since November of 1920. Such figures make İsmet Pașa's estimate all the more credible. Since approximately 640,000 Muslims died in the region of occupation during the war, one can estimate that approximately 860,000 were refugees who survived the war. Of course many, if not most, of those who died were refugees, as well. If one estimates that half the Muslims who died were refugees, it would be roughly accurate to say that 1.2 million Anatolian Muslim refugees fled from the Greeks, and about one-third died.

- ^ Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2015). World War I and the end of the Ottomans : from the Balkan wars to the Armenian genocide. Kerem Öktem, Maurus Reinkowski. London. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-85772-744-2. OCLC 944309903.