1959 Mosul uprising

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2014) |

| 1959 Mosul uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Cold War and Aftermath of the 14 July Revolution | |||||||

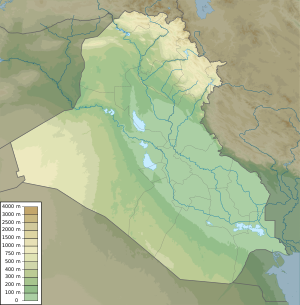

Mosul | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

(Leader of parading Communists) |

(Commander of Iraqi Army Mosul Garrison) (Leader of the Shammar Tribe) (President of the United Arab Republic) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,426[4] | |||||||

The 1959 Mosul Uprising was an attempted coup by Arab nationalists in Mosul who wished to depose the then Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim, and install an Arab nationalist government which would then join the Republic of Iraq with the United Arab Republic. Following the failure of the coup, law and order broke down in Mosul, which witnessed several days of violent street battles between various groups attempting to use the chaos to settle political and personal scores.

Background[]

During Qasim's term, there was much debate over whether Iraq should join the United Arab Republic, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan had dissolved the Arab Federation after Qasim had the entire royal family in Iraq put to death, along with Prime Minister Nuri al-Said.

Qasim's growing ties with the Iraqi Communist Party provoked a rebellion in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul which was led by Arab nationalists in charge of military units. In an attempt to intimidate any individuals plotting a potential coup, Qasim had encouraged a Communist backed Peace Partisans rally in Mosul that was held on 6 March 1959. Some 250,000 Peace Partisans and Communists thronged Mosul's streets on 6 March, and although the rally passed peacefully, by 7 March, skirmishes had broken out between the Communists and the nationalists. This degenerated into a local civil war over the following days.

Attempted coup[]

Qasim's attempt to stop dissent was successful to some extent, as Colonel Abdel Wahab Shawaf, the stocky 40-year-old Arab nationalist Commander of the Iraqi Army's Mosul Garrison, was discomforted by the Communists' show of force. Following clashes between the Communist Party's Popular Resistance Militia and local Nasserites which culminated in the burning down of a Nasserite restaurant, Shawaf phoned Baghdad to ask for permission to use the soldiers under his command to keep order.[5]

Shawaf was given an ambiguous response by Baghdad. So Shawaf decided to try and carry out a coup d'état on 7 March. Shawaf was supported in this endeavour by other disgruntled Free Officers, who were primarily from prominent Arab Sunni families and who opposed Qasim's growing relationship with the Iraqi Communist Party.[6] Shawaf ordered the fifth brigade, which was under his command, to round up 300 members of the Communist Peace Partisans, including their leader, , a well known Baghdad lawyer and politician, who was executed.[5]

Shawaf sent word to other northern Iraqi Army commanders in an effort to convince them to join his attempted coup. He kidnapped a British technician and portable radio transmitter from the Iraq Petroleum Company and took over Radio Mosul, which he attempted to use to encourage Iraqis to rise up against Qasim.[5] Shawaf also sent word to sympathetic local tribesmen, including the Shammar, of whom thousands then travelled to Mosul to show their support.[5]

On the morning of 8 March, Shawaf sent two Furies to Baghdad on an aerial bombing raid. The crew of the aircraft had been ordered to bomb the headquarters of Radio Baghdad. The raid was a failure, with the planes doing little damage. In response, Qasim sent four Iraqi Air Force planes to attack Shawaf's headquarters, situated on a bluff above Mosul. The attack on the headquarters killed six or seven officers, and wounded Shawaf. Whilst Shawaf was bandaging himself, he was killed by one of his sergeants who believed the coup had failed.[5]

Ensuing violence[]

Although Shawaf was dead, the violence was not yet over. Mosul soon became a scene of score settling between rebel and loyalist soldiers, alongside Communists and Arab nationalists. Bedouin tribesmen who had been called on by Shawaf prior to his death to support the coup also engaged in pillaging, and the violence within Mosul was also used as a cover by some to settle private scores. Shawaf's body was beaten and dragged through the streets of Mosul before being thrown in a car and taken to Baghdad.[5]

Three pro-government Kurdish tribes moved into Mosul and fought the Arab Shammar tribesmen, their long time opponents who had rallied around Shawaf. Sheik Ahmed Ajil, the chief of the Shammars was spotted by Kurdish militiamen in his car and was killed, along with his driver, and both were later hung naked from a bridge over the Tigris.[5]

By the fourth day government troops had begun to impose order and began clearing the roads as well as removing naked and mutilated bodies which had been strung up from lamp posts. The total dead was estimated at approximately 500.[5]

Aftermath[]

Although the rebellion was crushed by the military, it had a number of adverse effects that was to affect Qasim's position. First, it increased the power of the communists. Second, it encouraged the ideas of the Ba’ath Party's (which had been steadily growing since the 14 July coup). The Ba’ath Party believed that the only way of halting the engulfing tide of communism was to assassinate Qasim.

Of the 16 members of Qasim's cabinet, 12 of them were Ba'ath Party members. However, the party turned against Qasim due to his refusal to join Gamel Abdel Nasser's United Arab Republic.[7] To strengthen his own position within the government, Qasim created an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party, which was opposed to any notion of pan-Arabism.[8] By later that year, the Ba'ath Party leadership was planning to assassinate Qasim. Saddam Hussein was a leading member of the operation. At the time, the Ba'ath Party was more of an ideological experiment then a strong anti-government fighting machine. The majority of its members were either educated professionals or students, and Saddam fitted in well.[9] The choice of Saddam was, according to historian Con Coughlin, "hardly surprising". The idea of assassinating Qasim may have been Nasser's, and there is speculation that some of those who participated in the operation received training in Damascus, which was then part of the UAR. However, "no evidence has ever been produced to implicate Nasser directly in the plot."[10]

The assassins planned to ambush Qasim at Al-Rashid Street on 7 October 1959: one man was to kill those sitting at the back of the car, the rest killing those in front. During the ambush it is claimed that Saddam began shooting prematurely, which disorganised the whole operation. Qasim's chauffeur was killed, and Qasim was hit in the arm and shoulder. The assassins believed they had killed him and quickly retreated to their headquarters, but Qasim survived.[11]

The growing influence of communism was felt throughout 1959. A communist-sponsored purge of the armed forces was carried out in the wake of the Mosul revolt. The Iraqi cabinet began to shift towards the radical-left as several communist sympathisers gained posts in the cabinet. Iraq's foreign policy began to reflect this communist influence, as Qasim removed Iraq from the Baghdad Pact on 24 March, and later fostered closer ties with the USSR, including extensive economic agreements.[12] However communist successes encouraged attempts to expand on their position. The communists attempted to replicate their success at Mosul in similar fashion at Kirkuk. A rally was called for 14 July. This was intended to intimidate conservative elements. Instead, it resulted in widespread bloodshed.[13] Qasim consequently cooled relations with the communists signalling a reduction (although by no means a cessation) of their influence in the Iraqi government.[citation needed]

Qasim and his supporters accused the UAR of having supported the rebels,[5] and the uprising resulted in an intensification of the ongoing Iraq-UAR propaganda war,[14] with the UAR press accusing Qasim of having sold out the ideas of Arab nationalism. The disagreements between Qasim and Cairo also highlighted the fact that the UAR had failed to become the single voice of Arab nationalism, and the UAR had to recognize that many Iraqis were unwilling to recognise Cairo's leadership, thereby revealing the limits of Nasser's power to other Arab governments.[15]

Extent of UAR involvement[]

Although the attempted coup may have been driven in part by Arab nationalist sentiment and a desire to join the United Arab Republic, the exact extent of UAR involvement in the coup has largely been unclear. Shawaf kept in close contact with the UAR during the development of the attempted coup, with some claiming that the UAR ambassador in Baghdad acted as an intermediary between the UAR and the rebels. There is also evidence that suggests that Radio Mosul may have been transmitting from the Syrian side of the border.[16]

References[]

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Wolf-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2011). The End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 1958-1972. Stanford University. p. 36.

- ^ Davies, Eric (2005). Memories of State: Politics, History, and Collective Identity in Modern Iraq. University of California Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780520235465.

- ^ Podeh, Elie (1999). The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arab Republic. Sussex Academic Press. p. 85. ISBN 1-902210-20-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "IRAQ: The Revolt That Failed". Time. 23 March 1959. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Iraqi Revolution and Coups

- ^ Coughlin, Con (2005). Saddam: His Rise and Fall. Harper Perennial. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-06-050543-5.

- ^ Coughlin, Con (2005). Saddam: His Rise and Fall. Harper Perennial. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-06-050543-5.

- ^ Coughlin, Con (2005). Saddam: His Rise and Fall. Harper Perennial. p. 26. ISBN 0-06-050543-5.

- ^ Coughlin, Con (2005). Saddam: His Rise and Fall. Harper Perennial. p. 27. ISBN 0-06-050543-5.

- ^ Coughlin, Con (2005). Saddam: His Rise and Fall. Harper Perennial. p. 30. ISBN 0-06-050543-5.

- ^ Marr, Phebe; “The Modern History of Iraq”, page 164

- ^ Batatu, Hanna (2004). The Old Social Classes & The Revolutionary Movement In Iraq (PDF). Saqi Books. pp. 912–921. ISBN 978-0863565205. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Podeh, Elie (1999). The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arab Republic. Sussex Academic Press. p. 87. ISBN 1-902210-20-4.

- ^ Podeh, Elie (1999). The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arab Republic. Sussex Academic Press. p. 88. ISBN 1-902210-20-4.

- ^ Podeh, Elie (1999). The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arab Republic. Sussex Academic Press. p. 86. ISBN 1-902210-20-4.

- Arab nationalism in Iraq

- Arab nationalist rebellions

- Arab rebellions in Iraq

- 1950s coups d'état and coup attempts

- 1959 in Iraq

- 20th century in Iraq

- Communism in Iraq

- Conflicts in 1959

- Egypt–Iraq relations

- Military coups in Iraq

- Rebellions in Iraq

- Attempted coups d'état

- History of the Ba'ath Party