Turkish–Armenian War

Some of this article's listed sources may not be reliable. (May 2013) |

| Turkish–Armenian war | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Turkish War of Independence, the Aftermath of World War I, and Armenian–Turkish Conflict | |||||||||

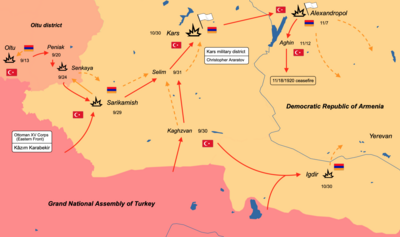

Map of Turkish-Armenian War (1920) and Turkish advance into territory controlled by Armenia | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

–60,000[7][8] |

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| unknown | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

The Turkish–Armenian war (Armenian: հայ-թուրքական պատերազմ), known in Turkey as the Eastern Front (Turkish: Doğu Cephesi) of the Turkish War of Independence, was a conflict in late 1920 between the First Republic of Armenia and the Turkish National Movement following the collapse of the Treaty of Sèvres. After the provisional government of Ahmet Tevfik Pasha failed to win support for ratification of the treaty, remnants of the Ottoman Army’s XV Corps under the command of Kâzım Karabekir attacked Armenian forces controlling the area surrounding Kars, eventually recapturing all territory previously ceded to the Ottoman Empire by Soviet Russia as part of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The Turkish military victory was followed by the Soviet Union's occupation and Sovietization of Armenia. The Treaty of Moscow (March 1921) between Soviet Russia and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and the related Treaty of Kars (October 1921) confirmed the territorial gains made by Karabekir and established the modern Turkish–Armenian border.

Background[]

The dissolution of the Russian Empire in the wake of the February Revolution saw the Armenians of the South Caucasus declaring their independence and formally establishing the First Republic of Armenia.[13] In its two years of existence, the tiny republic, with its capital in Yerevan, was beset with a number of debilitating problems, ranging from fierce territorial disputes with its neighbors and an appalling refugee crisis.[14]

Armenia's most crippling problem was its dispute with its neighbor to the west, the Ottoman Empire. Approximately 1.5 million Armenians had perished during the Armenian genocide. Although the armies of the Ottoman Empire eventually occupied the South Caucasus in the summer of 1918 and stood poised to crush the republic, Armenia resisted until the end of October, when the Ottoman Empire capitulated to the Allied powers. Though the Ottoman Empire was partially occupied by the Allies, and while being invaded by Franco-Armenian forces of the Cilicia Campaign, the Turks did not withdraw their forces to the pre-war Russo-Turkish boundary until February 1919 and maintained many troops mobilized along this frontier.[15]

Bolshevik and Turkish nationalist movements[]

During the First World War and in the ensuing peace negotiations in Paris, the Allies had vowed to punish the Turks and reward some, if not all, the eastern provinces of the empire to the nascent Armenian republic.[16] But the Allies were more concerned with concluding the peace treaties with Germany and the other European members of the Central Powers. In matters related to the Near East, the principal powers, Great Britain, France, Italy and the United States, had conflicting interests over the spheres of influence they were to assume. While there were crippling internal disputes between the Allies, and the United States was reluctant to accept a mandate over Armenia, disaffected elements in the Ottoman Empire in 1920 began to disavow the decisions made by the Ottoman government in Constantinople, coalesced and formed the Turkish National Movement, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha.[17] The Turkish Nationalists considered any partition of formerly Ottoman lands (and subsequent distribution to non-Turkish authorities) to be unacceptable. Their avowed goal was to "guarantee the safety and unity of the country."[18] The Bolsheviks sympathized with the Turkish Movement due to their mutual opposition to "Western Imperialism," as the Bolsheviks referred to it.[19]

In his message to Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks, dated 26 April 1920, Kemal promised to coordinate his military operations with the Bolsheviks' "fight against imperialist governments" and requested five million lira in gold as well as armaments "as first aid" to his forces.[20] In 1920, the Lenin government supplied the Kemalists with 6,000 rifles, more than five million rifle cartridges, and 17,600 projectiles, as well as 200.6 kg of gold bullion; in the following two years the amount of aid increased.[21] In the negotiations of the Treaty of Moscow (1921), the Bolsheviks demanded that the Turks cede Batum and Nakhichevan; they also asked for more rights in the future status of the Straits.[22] Despite the concessions made by the Turks, the financial and military supplies were slow in coming.[22] Only after the decisive Battle of Sakarya (August–September 1921), the aid started to flow in faster.[22] After much delays, the Armenians received from the Allies in July 1920 about 40,000 uniforms and 25,000 rifles with a great amount of ammunition.[23]

It was not until August 1920 that the Allies drafted the peace settlement of the Near East, in the form of the Treaty of Sèvres. The United States had refused to assume the Armenian mandate in May of that year, but the Allies delegated the US to draw the western boundaries of the republic. The US allotted four of the six eastern provinces to the Ottoman Empire, including an outlet to the Black Sea.[24] The Treaty of Sèvres served to confirm Kemal's suspicions about Allied plans to partition the empire. According to the historian Richard G. Hovannisian, his decision to order the invasion of Armenia was intended to show the Allies that "the treaty would not be accepted and that there would be no peace until the West was ready to offer new terms in keeping with the principles of the Turkish National Pact."[25]

Active stage[]

Early phases[]

According to Turkish and Soviet sources, Turkish plans to take back formerly Ottoman-controlled lands in the east were already in place as early as June 1920.[26] Using Turkish sources, Bilâl Şimşir has identified mid-June as to when exactly the Ankara government began to prepare for a campaign in the east.[27] Hostilities were first began by Kemalist forces.[28] Kâzım Karabekir was assigned command of the newly formed Eastern Front on June 9, 1920[29] and was given the authority of a field army over all civil and military officials in the Eastern Front on June 13 or 14.[30] Skirmishes between Turkish and Armenian forces in the area surrounding Kars were frequent during that summer, although full-scale hostilities did not break out until September. Convinced that the Allies would not come to the defense of Armenia and aware that the ADR's leaders had failed to gain recognition of its independence by Soviet Russia, Kemal gave the order to commanding general Kâzım Karabekir to advance into Armenian-held territory.[31] At 2:30 in the morning of September 13, five battalions from the Turkish XV Army Corps attacked Armenian positions, surprising the thinly spread and unprepared Armenian forces at Oltu and Penek. By dawn, Karabekir's forces had occupied Penek and the Armenians had suffered at least 200 casualties and been forced to retreat east towards Sarıkamış.[32] As neither the Allied powers nor Soviet Russia reacted to Turkish operations, on September 20 Kemal authorized Karabekir to push onwards and take Kars and Kağızman.

By this time, Karabekir's XV Corps had grown to the size of four divisions. At 3:00 in the morning of September 28, the four divisions of the XV Army Corps advanced towards Sarıkamış, creating such panic that Armenian residents had abandoned the town by the time the Turks entered the next day.[33] The armed forces started toward Kars but were delayed by Armenian resistance. In early October, the Armenian government pleaded that the Allies intervene and put a halt to the Turkish advance, to no avail. Most of Britain's available forces in the Near East were concentrated on crushing the tribal uprisings in Iraq, while France and Italy were also fighting the Turkish revolutionaries near Syria and Italian controlled Antalya.[34] Neighboring Georgia declared neutrality during the conflict.

On October 11, Soviet plenipotentiary Boris Legran arrived in Yerevan with a text to negotiate a new Soviet-Armenian agreement.[35] The agreement signed at October 24 secured Soviet support.[35] The most important part of this agreement dealt with Kars, which Armenia agreed to secure.[35] The Turkish national movement was not happy with possible agreement between the Soviets and Armenia. Karabekir was informed by the Government of the Grand National Assembly regarding the Boris Legran agreement and ordered to resolve the Kars issue. The same day the agreement between Armenia and Soviet Russia was signed, Karabekir moved his forces toward Kars.

Capture of Kars and Alexandropol[]

On October 24, Karabekir's forces launched a new, massive campaign against Kars.[34] The Armenians abandoned the city, which by October 30 came under full Turkish occupation.[36] Turkish forces continued to advance, and a week after the capture of Kars, they took control of Alexandropol (present-day Gyumri, Armenia.)[1] On November 12, the Turks also captured the strategic village of Aghin, northeast of the ruins of the former Armenian capital of Ani, and planned to move toward Yerevan. On November 13, Georgia broke its neutrality. It had concluded an agreement with Armenia to invade the disputed region of Lori, which was established as a Neutral Zone (the Shulavera Condominium) between the two nations in early 1919.[37]

Treaty of Alexandropol[]

The Turks, headquartered in Alexandropol, presented the Armenians with an ultimatum which they were forced to accept. They followed it with a more radical demand which threatened the existence of Armenia as a viable entity. The Armenians at first rejected this demand, but when Karabekir's forces continued to advance, they had little choice but to capitulate.[34] On November 18, 1920, they concluded a cease-fire agreement.[1] During the invasion the Turkish Army carried out mass atrocities against Armenian civilians in Kars and Alexandropol. These included rapes and massacres where tens of thousands of civilians were executed.[10][11][12]

As the terms of defeat were being negotiated between Karabekir and Armenian Foreign Minister Alexander Khatisyan, Joseph Stalin, on the command of Vladimir Lenin, ordered Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze to enter Armenia from Azerbaijan in order to establish a new pro-Bolshevik government in the country. On November 29, the Soviet Eleventh Army invaded Armenia at Karavansarai (present-day Ijevan).[34]

After the capture of Yerevan and Echmiadzin by Bolshevik forces on 2 December 1920, the Armenian government signed the Treaty of Alexandropol on 3 December 1920, though it no longer existed as a legal entity.[1] The treaty required Armenia to disarm most of its military forces, and cede all Ottoman territory that had been granted to Armenia by the Treaty of Sèvres. The Armenian Parliament never ratified the treaty, as the Soviet invasion took place at the same time and the communists took over the country.

Aftermath[]

In late November 1920, there was a Soviet-backed communist uprising in Armenia. On November 28, 1920, blaming Armenia for the invasions of Şərur (20 November) and Karabakh (21 November), the 11th Red Army under the command of Anatoli Gekker crossed the demarcation line between Armenia and Soviet Azerbaijan. The second Soviet-Armenian war lasted a week. Exhausted by the six years of wars and conflicts, the Armenian army and population were incapable of active resistance.

When the Red Army entered Yerevan on December 4, 1920, the government of Armenian Republic effectively surrendered. On December 5, the Armenian Revolutionary Committee (Revkom, consisting mostly of Armenians from Azerbaijan) also entered the city. Finally, on December 6, the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky's secret police, entered Yerevan. The Soviets took control and Armenia ceased to exist as an independent state.[34] Soon afterward, the bolsheviks declared the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Settlement[]

The warfare in Transcaucasia was settled in a friendship treaty between the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (GNAT) (which proclaimed the Turkish Republic in 1923), and Soviet Russia (RSFSR). The "Treaty on Friendship and Brotherhood," called the Treaty of Moscow, was signed on March 16, 1921. The succeeding Treaty of Kars, signed by the representatives of Azerbaijan SSR, Armenian SSR, Georgian SSR, and the GNAT, ceded Adjara to Soviet Georgia in exchange for the Kars territory (today the Turkish provinces of Kars, Iğdır, and Ardahan). Under the treaties, an autonomous Nakhichevan oblast was established under Azerbaijan's protectorate.

See also[]

- Armenia–Turkey border

- Armenian–Azerbaijani War

- Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

- Caucasus Campaign

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Andrew Andersen". www.conflicts.rem33.com. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ Andrew Andersen, Turkish-Armenian war: Sep.24 – Dec.2, 1920

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. Armenia: A Historical Atlas, p. 237. ISBN 0-226-33228-4

- ^ (In Russian) Turso Armenian Conflict

- ^ Kadishev, A.B. (1960), Интервенция и гражданская война в Закавказье [Intervention and civil war in the South Caucasus], Moscow, p. 324

- ^ Andersen, Andrew. "TURKEY AFTER WORLD WAR I: LOSSES AND GAINS". Centre for Military and Strategic Studies.

- ^ Guaita, Giovanni (2001), 1700 Years of Faithfulness: History of Armenia and its Churches, Moscow: FAM, ISBN 5-89831-013-4

- ^ Asenbauer, Haig E. (December 19, 1996). "On the right of self-determination of the Armenian people of Nagorno-Karabakh". Armenian Prelacy. Retrieved December 19, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ (in French) Ter Minassian, Anahide (1989). La république d'Arménie. 1918–1920 La mémoire du siècle. Brussels: éditions complexe, p. 220. ISBN 2-87027-280-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c These are according to the figures provided by Alexander Miasnikyan, the President of the Council of People's Commissars of Soviet Armenia, in a telegram he sent to the Soviet Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin in 1921. Miasnikyan's figures were broken down as follows: of the approximately 60,000 Armenians who were killed by the Turkish armies, 30,000 were men, 15,000 women, 5,000 children, and 10,000 young girls. Of the 38,000 who were wounded, 20,000 were men, 10,000 women, 5,000 young girls, and 3,000 children. Instances of mass rape, murder and violence were also reported against the Armenian populace of Kars and Alexandropol: see Vahakn N. Dadrian. (2003). The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 360–361. ISBN 1-57181-666-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Armenia: The Survival of a Nation, Christopher Walker, 1980.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Akçam, Taner (2007). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. pp. 327. - Profile at Google Books

- ^ For the period leading up to independence see Richard G. Hovannisian (1967). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00574-0.

- ^ The full history of the Armenian republic is covered by Richard G. Hovannisian, Republic of Armenia. 4 Vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971–1996.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918–1919, Vol. I. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 416ff. ISBN 0-520-01984-9.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. "The Allies and Armenia, 1915–18." Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 3, No. 1 (Jan., 1968), pp. 145–168.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia, Vol. II: From Versailles to London, 1919–1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 20–39, 316–364, 404–530. ISBN 0-520-04186-0.

- ^ "Turkish War of Independence - All About Turkey". www.allaboutturkey.com. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. "Armenia and the Caucasus in the Genesis of the Soviet-Turkish Entente." International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2 (April, 1973), pp. 129–147.

- ^ (in Russian) Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn, 1963, № 11, pp. 147–148. The first publication of Kemal's letter to Lenin, in excerpts, in Russian.

- ^ (in Russian) Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn, 1963, № 11, p. 148.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Erik J. Zürcher: Turkey: A Modern History, I.B.Tauris, 2004, ISBN 1860649580, p. 153.

- ^ (French) Ter Minassian, Anahide (1989). La république d'Arménie. 1918–1920 La mémoire du siècle, Brussels: Éditions complexe, ISBN 2-87027-280-4, p. 196.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, p. 180.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, p. 194, note 27.

- ^ (in Turkish) Şimşir, Bilâl N. Ermeni Meselesi, 1774–2005 (The Armenian Question, 1774–2005). Bilgi Yayınevi, 2005, p. 182.

- ^ Sarkisi︠a︡n, Ervand Kazarovich; Sargsyan, Ervand Ghazari; Sahakian, Ruben G. (December 19, 1965). "Vital issues in modern Armenian history: a documented exposé of misrepresentations in Turkish historiography". Armenian Studies. Retrieved December 19, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ (in Turkish) T.C. Genelkurmay Harp Tarihi Başkanlığı Yayınları, Türk İstiklâl Harbine Katılan Tümen ve Daha Üst Kademelerdeki Komutanların Biyografileri, Genkurmay Başkanlığı Basımevi, Ankara, 1972.

- ^ "Kâzım Karabekir Paşa, Doğu Cephesi'nde bulunan bütün sivil ve askeri makamlar üzerinde seferdeki ordu komutanlığı yetkisine haizdir": (in Turkish) Kemal Atatürk, Atatürk'ün bütün Eserleri: 23 Nisan-7/8 Temmuz 1920 (The Complete Works of Atatürk: 23 April-7/8 July). Kaynak Yayınları, 2002, p. 314. ISBN 978-975-343-349-5.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, pp. 184–190.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, pp. 191–197.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 237. ISBN 0-226-33228-4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, p. 259.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, pp. 253–261.

- ^ Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV, pp. 222–226.

- Turkish–Armenian War

- Conflicts in 1920

- 1920 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1920 in Armenia

- Wars involving Turkey

- Wars involving Armenia