Central Powers

Central Powers Mittelmächte (German) Központi hatalmak (Hungarian) İttifak Devletleri (Turkish) Централни сили (Bulgarian) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914–1918 | |||||||||||||||

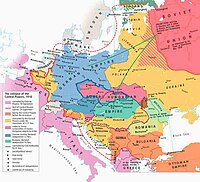

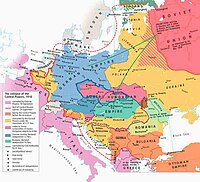

The Central Powers in orange as of 1 August 1914

| |||||||||||||||

| Status | Military alliance | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | World War I | ||||||||||||||

| 7 October 1879 | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 28 June 1914 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 August 1914 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| 11 November 1918 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

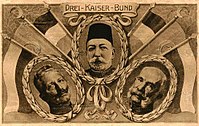

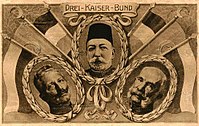

- Leaders of the Central Powers (left to right):

- Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany;

- Kaiser and King Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary;

- Sultan Mehmed V of the Ottoman Empire;

- Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,[1][notes 1] was one of the two main coalitions that fought World War I (1914–18). It consisted of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria; hence it is also known as the Quadruple Alliance.[2][notes 2] Colonies of these countries also fought on the Central Powers' side such as German New Guinea and German East Africa, until almost all of their colonies were occupied by the Allies.

The Central Powers faced and were defeated by the Allied Powers that had formed around the Triple Entente. The Central Powers' origin was the alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1879. Despite having nominally joined the Triple Alliance before, Italy did not take part in World War I on the side of the Central Powers. The Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria did not join until after World War I had begun, even though the Ottoman Empire had retained close relations with both Germany and Austria-Hungary since the beginning of the 20th century.

Member states[]

The Central Powers consisted of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the beginning of the war. The Ottoman Empire joined later in 1914, followed by the Kingdom of Bulgaria in 1915. The name "Central Powers" is derived from the location of these countries; all four (including the other groups that supported them except for Finland and Lithuania) were located between the Russian Empire in the east and France and the United Kingdom in the west. Finland, Azerbaijan, and Lithuania joined them in 1918 right before the war ended and after the Russian Empire collapsed.

- Allied and Central Powers during World War I

- Allied Powers

- Allied colonies, dominions, territories or occupations

- Central Powers

- Central Powers' colonies or occupations

- Neutral countries

The Central Powers were composed of the following nations:[3]

| Nation | Entered WWI |

|---|---|

| 28 July 1914 | |

| 1 August 1914 | |

| 2 August 1914 (secret) 29 October 1914 (public) | |

| 14 October 1915 |

| Population (millions) |

Land (million km2) |

GDP ($ billion) |

GDP per capita ($) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainland | 67.0 | 0.5 | 244.3 | 3,648 | |

| Colonies | 10.7 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 601 | |

| Total | 77.7 | 3.5 | 250.7 | 3,227 | |

| 50.6 | 0.6 | 100.5 | 1,986 | ||

| 23.0 | 1.8 | 25.3 | 1,100 | ||

| 4.8 | 0.1 | 7.4 | 1,527 | ||

| Total | 156.1 | 6.0 | 383.9 | 2,459 | |

| Mobilized | Killed in action | Wounded | Missing in action | Total casualties | Percentage casualties of total force mobilized | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13,250,000 | 1,808,546 (13.65%) | 4,247,143 | 1,152,800 | 7,208,489 | 66% | |

| 7,800,000 | 922,500 (11.82%) | 3,620,000 | 2,200,000 | 6,742,500 | 86% | |

| 2,998,321 | 325,000 (10.84%) | 400,000 | 250,000 | 975,000 | 34% | |

| 1,200,000 | 75,844 (6.32%) | 153,390 | 27,029 | 255,263 | 21% | |

| Total | 25,257,321 | 3,131,890 | 8,419,533 | 3,629,829 | 15,181,252 | 66% |

Combatants[]

Germany[]

War justifications[]

In early July 1914, in the aftermath of the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the immediate likelihood of war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Kaiser Wilhelm II and the German government informed the Austro-Hungarian government that Germany would uphold its alliance with Austria-Hungary and defend it from possible Russian intervention if a war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia took place.[6] When Russia enacted a general mobilization, Germany viewed the act as provocative.[7] The Russian government promised Germany that its general mobilization did not mean preparation for war with Germany but was a reaction to the events between Austria-Hungary and Serbia.[7] The German government regarded the Russian promise of no war with Germany to be nonsense in light of its general mobilization, and Germany, in turn, mobilized for war.[7] On 1 August, Germany sent an ultimatum to Russia stating that since both Germany and Russia were in a state of military mobilization, an effective state of war existed between the two countries.[8] Later that day, France, an ally of Russia, declared a state of general mobilization.[8]

In August 1914, Germany waged war on Russia, citing Russian aggression as demonstrated by the mobilization of the Russian army, which had resulted in Germany mobilizing in response.[9]

After Germany declared war on Russia, France, with its alliance with Russia, prepared a general mobilization in expectation of war. On 3 August 1914, Germany responded to this action by declaring war on France.[10] Germany, facing a two-front war, enacted what was known as the Schlieffen Plan, which involved German armed forces needing to move through Belgium and swing south into France and towards the French capital of Paris. This plan was hoped to quickly gain victory against the French and allow German forces to concentrate on the Eastern Front. Belgium was a neutral country and would not accept German forces crossing its territory. Germany disregarded Belgian neutrality and invaded the country to launch an offensive towards Paris. This caused Great Britain to declare war against the German Empire, as the action violated the Treaty of London that both nations signed in 1839 guaranteeing Belgian neutrality and defense of the kingdom if a nation reneged.

Subsequently, several states declared war on Germany in late August 1914, with Italy declaring war on Austria-Hungary in 1915 and Germany on 27 August 1916, the United States declaring war on Germany on 6 April 1917 and Greece declaring war on Germany in July 1917.

Colonies and dependencies[]

- Europe

Upon its founding in 1871, the German Empire controlled Alsace-Lorraine as an "imperial territory" incorporated from France after the Franco-Prussian War. It was held as part of Germany's sovereign territory.

- Africa

Germany held multiple African colonies at the time of World War I. All of Germany's African colonies were invaded and occupied by Allied forces during the war.

Kamerun, German East Africa, and German Southwest Africa were German colonies in Africa. Togoland was a German protectorate in Africa.

- Asia

The Kiautschou Bay concession was a German dependency in East Asia leased from China in 1898. Japanese forces occupied it following the Siege of Tsingtao.

- Pacific

German New Guinea was a German protectorate in the Pacific. It was occupied by Australian forces in 1914.

German Samoa was a German protectorate following the Tripartite Convention. It was occupied by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1914.

Austria-Hungary[]

War justifications[]

Austria-Hungary regarded the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as being orchestrated with the assistance of Serbia.[6] The country viewed the assassination as setting a dangerous precedent of encouraging the country's South Slav population to rebel and threaten to tear apart the multinational country.[7] Austria-Hungary formally sent an ultimatum to Serbia demanding a full-scale investigation of Serbian government complicity in the assassination and complete compliance by Serbia in agreeing to the terms demanded by Austria-Hungary.[6] Serbia submitted to accept most of the demands. However, Austria-Hungary viewed this as insufficient and used this lack of full compliance to justify military intervention.[11] These demands have been viewed as a diplomatic cover for what was going to be an inevitable Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia.[11]

Russia had warned Austria-Hungary that the Russian government would not tolerate Austria-Hungary invading Serbia.[11] However, with Germany supporting Austria-Hungary's actions, the Austro-Hungarian government hoped that Russia would not intervene and that the conflict with Serbia would remain a regional conflict.[6]

Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia resulted in Russia declaring war on the country, and Germany, in turn, declared war on Russia, setting off the beginning of the clash of alliances that resulted in the World War.

- Territory

Austria-Hungary was internally divided into two states with their own governments, joined in communion through the Habsburg throne. Austrian Cisleithania contained various duchies and principalities but also the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Kingdom of Dalmatia, the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. Hungarian Transleithania comprised the Kingdom of Hungary and the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, sovereign authority was shared by both Austria and Hungary.

Ottoman Empire[]

War justifications[]

The Ottoman Empire joined the war on the side of the Central Powers in November 1914. The Ottoman Empire had gained strong economic connections with Germany through the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway project that was still incomplete at the time.[12] The Ottoman Empire made a formal alliance with Germany signed on 2 August 1914.[13] The alliance treaty expected that the Ottoman Empire would become involved in the conflict in a short amount of time.[13] However, for the first several months of the war, the Ottoman Empire maintained neutrality though it allowed a German naval squadron to enter and stay near the strait of Bosphorus.[14] Ottoman officials informed the German government that the country needed time to prepare for conflict.[14] Germany provided financial aid and weapons shipments to the Ottoman Empire.[13]

After pressure escalated from the German government demanding that the Ottoman Empire fulfill its treaty obligations, or else Germany would expel the country from the alliance and terminate economic and military assistance, the Ottoman government entered the war with the recently acquired cruisers from Germany, the Yavuz Sultan Selim (formerly SMS Goeben) and the Midilli (formerly SMS Breslau) launching a naval raid on the Russian port of Odessa, thus engaging in military action in accordance with its alliance obligations with Germany. Russia and the Triple Entente declared war on the Ottoman Empire.[15]

Bulgaria[]

War justifications[]

Bulgaria was still resentful after its defeat in July 1913 at the hands of Serbia, Greece and Romania. It signed a treaty of defensive alliance with the Ottoman Empire on 19 August 1914. It was the last country to join the Central Powers, which Bulgaria did in October 1915 by declaring war on Serbia. It invaded Serbia in conjunction with German and Austro-Hungarian forces. Bulgaria held claims on the region of Vardar Macedonia then held by Serbia following the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 and the Treaty of Bucharest (1913).[16] As a condition of entering WW1 on the side of the Central Powers, Bulgaria was granted the right to reclaim that territory.[17][18]

Declarations of war[]

| Date | Declared by | Declared against |

|---|---|---|

| 1915 | ||

| 14 October | ||

| 15 October | ||

| 16 October | ||

| 19 October | ||

| 1916 | ||

| 1 September | ||

| 1917 | ||

| 2 July | ||

Co-belligerents[]

South African Republic[]

In opposition to offensive operations by Union of South Africa, which had joined the war, Boer army officers of what is now known as the Maritz Rebellion "refounded" the South African Republic in September 1914. Germany assisted the rebels, some rebels operating in and out of the German colony of German South-West Africa. The rebels were all defeated or captured by South African government forces by 4 February 1915.

Senussi Order[]

The Senussi Order was a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in Libya, previously under Ottoman control, which had been lost to Italy in 1912. In 1915, they were courted by the Ottoman Empire and Germany, and Grand Senussi Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi declared jihad and attacked the Italians in Libya and British controlled Egypt in the Senussi Campaign.

Sultanate of Darfur[]

In 1915 the Sultanate of Darfur renounced allegiance to the Sudan government and aligned with the Ottomans. The Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition preemptively in March 1916 to prevent an attack on Sudan and took control of the Sultanate by November 1916.

Client states[]

During 1917 and 1918, the Finns under Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim and Lithuanian nationalists fought Russia for a common cause. With the Bolshevik attack of late 1917, the General Secretariat of Ukraine sought military protection first from the Central Powers and later from the armed forces of the Entente.

The Ottoman Empire also had its own allies in Azerbaijan and the Northern Caucasus. The three nations fought alongside each other under the Army of Islam in the Battle of Baku.

German client states[]

- Poland (Kingdom of Poland)

The Kingdom of Poland was a client state of Germany proclaimed in 1916 and established on 14 January 1917.[19] This government was recognized by the emperors of Germany and Austria-Hungary in November 1916, and it adopted a constitution in 1917.[20] The decision to create a Polish State was taken by Germany in order to attempt to legitimize its military occupation amongst the Polish inhabitants, following upon German propaganda sent to Polish inhabitants in 1915 that German soldiers were arriving as liberators to free Poland from subjugation by Russia.[21] The German government utilized the state alongside punitive threats to induce Polish landowners living in the German-occupied Baltic territories to move to the state and sell their Baltic property to Germans in exchange for moving to Poland. Efforts were made to induce similar emigration of Poles from Prussia to the state.[22]

- Lithuania (Kingdom of Lithuania)

The Kingdom of Lithuania was a client state of Germany created on 16 February 1918.

- Belarus (Belarusian People's Republic)

The Belarusian People's Republic was a client state of Germany created on 9 March 1918.

- Ukraine (Ukrainian State)

The Ukrainian State was a client state of Germany led by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi from 29 April 1918, after the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic was overthrown.[23]

- Courland and Semigallia

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was a client state of Germany created on 8 March 1918.

- Baltic State

The Baltic State also known as the "United Baltic Duchy", was proclaimed on 22 September 1918 by the Baltic German ruling class. It was to encompass the former Estonian governorates and incorporate the recently established Courland and Semigallia into a unified state. An armed force in the form of the Baltische Landeswehr was created in November 1918, just before the surrender of Germany, which would participate in the Russian Civil War in the Baltics.

- Finland (Kingdom of Finland)

Finland had existed as an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia since 1809, and the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 gave it its independence. Following the end of the Finnish Civil War, in which Germany supported the "White" against the Soviet-backed labour movement, in May 1918, there were moves to create a Kingdom of Finland. A German prince was elected, but the Armistice intervened.

- Crimea (Crimean Regional Government)

The Crimean Regional Government was a client state of Germany created on 25 June 1918.

- Georgia (Democratic Republic of Georgia)

The Democratic Republic of Georgia declared independence in 1918 which then led to border conflicts between the newly formed republic and Ottoman Empire. Soon after Ottoman Empire invaded the republic and quickly reached Borjomi. This forced Georgia to ask for help from Germany, which they were granted. Germany forced the Ottomans to withdraw from Georgian territories and recognize Georgian sovereignty. Germany, Georgia and the Ottomans signed a peace treaty, the Treaty of Batum which ended the conflict with the last two. In return, Georgia become a German "ally". This time period of Georgian-German friendship was known as German Caucasus expedition.

Ottoman client states[]

- Jabal Shammar

Jabal Shammar was an Arab state in the Middle East that was closely associated with the Ottoman Empire.[24]

- Azerbaijan (Azerbaijan Democratic Republic)

In 1918, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, facing Bolshevik revolution and opposition from the Muslim Musavat Party, was then occupied by the Ottoman Empire, which expelled the Bolsheviks while supporting the Musavat Party.[25] The Ottoman Empire maintained a presence in Azerbaijan until the end of the war in November 1918.[25]

- Northern Caucasus (Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus)

The Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus was associated with the Central Powers.

Controversial cases[]

States listed in this section were not officially members of the Central Powers. Still, during the war, they cooperated with one or more Central Powers members on a level that makes their neutrality disputable.

Ethiopia[]

The Ethiopian Empire was officially neutral throughout World War I but widely suspected of sympathy for the Central Powers between 1915 and 1916. At the time, Ethiopia was one of the few independent states in Africa and a major power in the Horn of Africa. Its ruler, Lij Iyasu, was widely suspected of harbouring pro-Islamic sentiments and being sympathetic to the Ottoman Empire. The German Empire also attempted to reach out to Iyasu, dispatching several unsuccessful expeditions to the region to attempt to encourage it to collaborate in an Arab Revolt-style uprising in East Africa. One of the unsuccessful expeditions was led by Leo Frobenius, a celebrated ethnographer and personal friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Under Iyasu's directions, Ethiopia probably supplied weapons to the Muslim Dervish rebels during the Somaliland Campaign of 1915 to 1916, indirectly helping the Central Powers' cause.[26]

Fearing the rising influence of Iyasu and the Ottoman Empire, the Christian nobles of Ethiopia conspired against Iyasu over 1915. Iyasu was first excommunicated by the Ethiopian Orthodox Patriarch and eventually deposed in a coup d'état on 27 September 1916. A less pro-Ottoman regent, Ras Tafari Makonnen, was installed on the throne.[26]

Non-state combatants[]

Other movements supported the efforts of the Central Powers for their own reasons, such as the radical Irish Nationalists who launched the Easter Rising in Dublin in April 1916; they referred to their "gallant allies in Europe". However, most Irish Nationalists supported the British and allied war effort up until 1916, when the Irish political landscape was changing. In 1914, Józef Piłsudski was permitted by Germany and Austria-Hungary to form independent Polish legions. Piłsudski wanted his legions to help the Central Powers defeat Russia and then side with France and the UK and win the war with them.

- Kaocen revolt

- Zaian War

- Irish Citizen Army

- Irish Republican Brotherhood

- Irish Volunteers

- White Guard (Finland)

- Hindu–German Conspiracy

- Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition

- Senussi Campaign

- Polish Legions

- Volta-Bani War

- BMORK

- Ahl Haydara Mansur

Armistice and treaties[]

Bulgaria signed an armistice with the Allies on 29 September 1918, following a successful Allied advance in Macedonia. The Ottoman Empire followed suit on 30 October 1918 in the face of British and Arab gains in Palestine and Syria. Austria and Hungary concluded ceasefires separately during the first week of November following the disintegration of the Habsburg Empire and the Italian offensive at Vittorio Veneto; Germany signed the armistice ending the war on the morning of 11 November 1918 after the Hundred Days Offensive, and a succession of advances by New Zealand, Australian, Canadian, Belgian, British, French and US forces in north-eastern France and Belgium. There was no unified treaty ending the war; the Central Powers were dealt with in separate treaties.[27]

|

|

Military deaths of the Central Powers

A postcard depicting the flags of the Central Powers' countries

The collapse of the Central Powers in 1918

The leaders of the Central Powers in 1914

Leaders[]

See also[]

- Central Powers intervention in the Russian Civil War

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- Home front during World War I covering all major countries

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Axis powers

Footnotes[]

- ^ German: Mittelmächte; Hungarian: Központi hatalmak; Turkish: İttifak Devletleri / Bağlaşma Devletleri; Bulgarian: Централни сили, romanized: Tsentralni sili

- ^ German: Vierbund, Turkish: Dörtlü İttifak, Hungarian: Központi hatalmak, Bulgarian: Четворен съюз, romanized: Chetvoren sūyuz

- ^ All figures presented are for the year 1913.

References[]

- ^ e.g. in Britain and the Olympic Games, 1908–1920 by Luke J. Harris p. 185

- ^ Hindenburg, Paul von (1920). Out of my life. Internet Archive. London : Cassell. p. 113.

- ^ Meyer, G.J. (2007). A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918. Delta Trade Paperback. ISBN 978-0-553-38240-2.

- ^ S.N. Broadberry, Mark Harrison. The Economics of World War I. illustrated ed. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Spencer Tucker (1996). The European Powers in the First World War. p. 173. ISBN 9780815303992.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cashman, Greg; Robinson, Leonard C. An Introduction to the Causes of War: Patterns of Interstate Conflict from World War I to Iraq. Rowman & Littlefield. 2007. P57

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Meyer, G.J. A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918. Delta Book. 2006. P39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyer, G.J. A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918. Delta Book. 2006. P95.

- ^ Hagen, William W. German History in Modern Times: Four Lives of the Nation. P228.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. 2009. P1556.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cashman, Greg; Robinson, Leonard C. An Introduction to the Causes of War: Patterns of Interstate Conflict from World War I to Iraq. Rowman & Littlefield. 2007. P61

- ^ Hickey, Michael. The First World War: Volume 4 The Mediterranean Front 1914–1923. P31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Afflerbach, Holger; David Stevenson, David. An Improbable War: The Outbreak of World War 1 and European Political Culture. Berghan Books. 2012. P. 292.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kent, Mary. The Great Powers and the End of the Ottoman Empire. end ed. Frank Cass. 1998. P119

- ^ Afflerbach, Holger; David Stevenson, David. An Improbable War: The Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture. Berghan Books. 2012. P. 293.

- ^ Hall, Richard C. "Bulgaria in the First World War". Russia's Great War and Revolution. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1986). The establishment of the Balkan national states, 1804–1920 (1st pbk. ed.). Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 284–297. ISBN 978-0-295-96413-3.

- ^ Richard C. Hall, "Bulgaria in the First World War." Historian 73.2 (2011): 300-315.

- ^ The Regency Kingdom has been referred to as a puppet state by Norman Davies in Europe: A history (Google Print, p. 910); by Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki in A Concise History of Poland (Google Print, p. 218); by Piotr J. Wroblel in Chronology of Polish History and Nation and History (Google Print, p. 454); and by Raymond Leslie Buell in Poland: Key to Europe (Google Print, p. 68: "The Polish Kingdom... was merely a pawn [of Germany]").

- ^ J. M. Roberts. Europe 1880–1945. P. 232.

- ^ Aviel Roshwald. Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, the Middle East and Russia, 1914–23. Routledge, 2002. P. 117.

- ^ Annemarie Sammartino. The Impossible Border: Germany and the East, 1914–1922. Cornell University, 2010. P. 36-37.

- ^ Kataryna Wolczuk. The Moulding of Ukraine: The Constitutional Politics of State Formation. P37.

- ^ Hala Mundhir Fattah. The Politics of Regional Trade in Iraq, Arabia, and the Gulf, 1745–1900. P121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zvi Lerman, David Sedik. Rural Transition in Azerbaijan. P12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "How Ethiopian prince scuppered Germany's WW1 plans". BBC News. 25 September 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Davis, Robert T., ed. (2010). U.S. Foreign Policy and National Security: Chronology and Index for the 20th Century. 1. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger Security International. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-38385-4.

Further reading[]

- Akin, Yigit. When the War Came Home: The Ottomans' Great War and the Devastation of an Empire (2018)

- Aksakal, Mustafa. The Ottoman Road to War in 1914: The Ottoman Empire and the First World War (2010).

- Brandenburg, Erich. (1927) From Bismarck to the World War: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914 (1927) online.

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013)

- Craig, Gordon A. "The World War I alliance of the Central Powers in retrospect: The military cohesion of the alliance." Journal of Modern History 37.3 (1965): 336–344. online

- Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo(1966), comprehensive history of the assassination with detailed material on the Austrian Empire and Serbia.

- Fay, Sidney B. The Origins of the World War (2 vols in one. 2nd ed. 1930). online, passim

- Gooch, G. P. Before The War Vol II (1939) pp 373–447 on Berchtold online free

- Hall, Richard C. "Bulgaria in the First World War." Historian 73.2 (2011): 300–315. online

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. Decisions for War, 1914–1917 (2004), scholarly essays on Serbia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France, Britain, Japan, Ottoman Empire, Italy, the United States, Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece.

- Herweg, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914–1918 (2009).

- Herweg, Holger H., and Neil Heyman. Biographical Dictionary of World War I (1982).

- Hubatsch, Walther. Germany and the Central Powers in the World War, 1914– 1918 (1963) online

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo. “Revising German History: Bethmann-Hollweg Revisited.” Central European History 21#3 (1988): 224–243, historiography in JSTOR

- Pribram, A. F. Austrian Foreign Policy, 1908–18 (1923) pp 68–128.

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Schmitt, Bernadotte E. The coming of the war, 1914 (2 vol 1930) comprehensive history online vol 1; online vol 2, esp vol 2 ch 20 pp 334–382

- Strachan, Hew. The First World War: Volume I: To Arms (2003).

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1996) 816pp

- Watson, Alexander. Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (2014)

- Wawro, Geoffrey. A Mad Catastrophe: The Outbreak of World War I and the Collapse of the Habsburg Empire (2014)

- Williamson, Samuel R. Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War (1991)

- Zametica, John. Folly and malice: the Habsburg empire, the Balkans and the start of World War One (London: Shepheard–Walwyn, 2017). 416pp.

- World War I

- 1914 establishments in Bulgaria

- 1914 establishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 1918 disestablishments in Austria-Hungary

- 1918 disestablishments in Bulgaria

- 1918 disestablishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 20th century in international relations

- 20th-century military alliances

- Austria-Hungary in World War I

- Bulgaria in World War I

- German Empire in World War I

- Germany–Ottoman Empire relations

- Military alliances involving Austria-Hungary

- Military alliances involving Bulgaria

- Military alliances involving the German Empire

- Military alliances involving the Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Empire in World War I