Causes of World War I

The identification of the causes of World War I remains controversial. World War I began in the Balkans on July 28, 1914 and hostilities ended on November 11, 1918, leaving 17 million dead and 25 million wounded.

Scholars looking at the long term seek to explain why two rival sets of powers (the German Empire and Austria-Hungary against the Russian Empire, France, the British Empire and later the United States) came into conflict by 1914. They look at such factors as political, territorial and economic competition; militarism, a complex web of alliances and alignments; imperialism, the growth of nationalism; and the power vacuum created by the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Other important long-term or structural factors that are often studied include unresolved territorial disputes, the perceived breakdown of the European balance of power,[1][2] convoluted and fragmented governance, the arms races of the previous decades, and military planning.[3]

Scholars seeking short-term analysis focus on the summer of 1914 ask whether the conflict could have been stopped or deeper causes made it inevitable. The immediate causes lay in decisions made by statesmen and generals during the July Crisis, which was triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by the Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip, who had been supported by a nationalist organization in Serbia.[4] The crisis escalated as the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia was joined by their allies Russia, Germany, France, and ultimately Belgium and the United Kingdom. Other factors that came into play during the diplomatic crisis leading up to the war included misperceptions of intent (such as the German belief that Britain would remain neutral), fatalism that war was inevitable, and the speed of the crisis, which was exacerbated by delays and misunderstandings in diplomatic communications.

The crisis followed a series of diplomatic clashes among the Great Powers (Italy, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Austria-Hungary and Russia) over European and colonial issues in the decades before 1914 that had left tensions high. In turn, the public clashes can be traced to changes in the balance of power in Europe since 1867.[5]

Consensus on the origins of the war remains elusive since historians disagree on key factors and place differing emphasis on a variety of factors. That is compounded by historical arguments changing over time, particularly as classified historical archives become available, and as perspectives and ideologies of historians have changed. The deepest division among historians is between those who see Germany and Austria-Hungary driving events and those who focus on power dynamics among a wider group of actors and factors. Secondary fault lines exist between those who believe that Germany deliberately planned a European war, those who believe that the war was largely unplanned but was still caused principally by Germany and Austria-Hungary taking risks, and those who believe that some or all of the other powers (Russia, France, Serbia, United Kingdom) played a more significant role in causing the war than has been traditionally suggested.

Polarization of Europe, 1887–1914[]

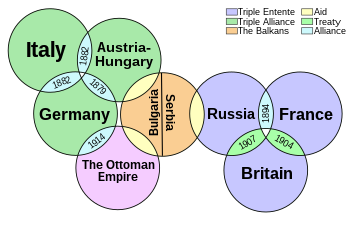

To understand the long-term origins of the war in 1914, it is essential to understand how the powers formed into two competing sets that shared common aims and enemies. Both sets became, by August 1914, Germany and Austria-Hungary on one side and Russia, France, and Britain on the other side.

German realignment to Austria-Hungary and Russian realignment to France, 1887–1892[]

1 2 3 4 | |||||||||||

Map of Bismarck's alliances

| |||||||||||

In 1887, German and Russian alignment was secured by means of a secret Reinsurance Treaty arranged by Otto von Bismarck. However, in 1890, Bismarck fell from power, and the treaty was allowed to lapse in favor of the Dual Alliance (1879) between Germany and Austria-Hungary. That development was attributed to Count Leo von Caprivi, the Prussian general who replaced Bismarck as chancellor. It is claimed that Caprivi recognized a personal inability to manage the European system as his predecessor had and so was counseled by contemporary figures such as Friedrich von Holstein to follow a more logical approach, as opposed to Bismarck's complex and even duplicitous strategy.[6] Thus, the treaty with Austria-Hungary was concluded despite the Russian willingness to amend the Reinsurance Treaty and to sacrifice a provision referred to as the "very secret additions"[6] that concerned the Turkish Straits.[7]

Caprivi's decision was also driven by the belief that the Reinsurance Treaty was no longer needed to ensure Russian neutrality if France attacked Germany, and the treaty would even preclude an offensive against France.[8] Lacking the capacity for Bismarck's strategic ambiguity, Caprivi pursued a policy that was oriented towards "getting Russia to accept Berlin's promises on good faith and to encourage St. Petersburg to engage in a direct understanding with Vienna, without a written accord."[8] By 1882, the Dual Alliance was expanded to include Italy.[9] In response, Russia secured in the same year the Franco-Russian Alliance, a strong military relationship that was to last until 1917. That move was prompted by Russia's need for an ally since it was experiencing a major famine and a rise in antigovernment revolutionary activities.[8] The alliance was gradually built throughout the years from when Bismarck refused the sale of Russian bonds in Berlin, which drove Russia to the Paris capital market.[10] That began the expansion of Russian and French financial ties, which eventually helped elevate the Franco-Russian entente to the diplomatic and military arenas.

Caprivi's strategy appeared to work when, during the outbreak of the Bosnian crisis of 1908, it successfully demanded for Russia to step back and demobilize.[11] When Germany asked Russia the same thing later, Russia refused, which finally helped precipitate the war.

French distrust of Germany[]

Some of the distant origins of World War I can be seen in the results and consequences of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–1871 and the concurrent unification of Germany. Germany had won decisively and established a powerful empire, but France fell into chaos and military decline for years. A legacy of animosity grew between France and Germany after the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. The annexation caused widespread resentment in France, giving rise to the desire for revenge that was known as revanchism. French sentiment was based on a desire to avenge military and territorial losses and the displacement of France as the pre-eminent continental military power.[12] Bismarck was wary of French desire for revenge and achieved peace by isolating France and by balancing the ambitions of Austria-Hungary and Russia in the Balkans. During his later years, he tried to placate the French by encouraging their overseas expansion. However, anti-German sentiment remained.[13]

France eventually recovered from its defeat, paid its war indemnity, and rebuilt its military strength. However, France was smaller than Germany in terms of population and industry and so many French felt insecure next to a more powerful neighbor.[14] By the 1890s, the desire for revenge over Alsace-Lorraine no longer was a major factor for the leaders of France but remained a force in public opinion. Jules Cambon, the French ambassador to Berlin (1907–1914), worked hard to secure a détente, but French leaders decided that Berlin was trying to weaken the Triple Entente and was not sincere in seeking peace. The French consensus was that war was inevitable.[15]

British alignment towards France and Russia, 1898–1907: The Triple Entente[]

After Bismarck's removal in 1890, French efforts to isolate Germany became successful. With the formation of the Triple Entente, Germany began to feel encircled.[16] French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé went to great pains to woo Russia and Britain. Key markers were the 1894 Franco-Russian Alliance, the 1904 Entente Cordiale with Britain, and the 1907 Anglo-Russian Entente, which became the Triple Entente. The informal alignment with Britain and formal alliance with Russia against Germany and Austria eventually led Russia and Britain to enter World War I as France's allies.[17][18]

Britain abandoned the splendid isolation in the 1900s after it had been isolated during the Second Boer War. Britain concluded agreements, limited to colonial affairs, with its two major colonial rivals: the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904 and the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907. Some historians see Britain's alignment as principally a reaction to an assertive German foreign policy and the buildup of its navy from 1898 that led to the Anglo-German naval arms race.[19][20]

Other scholars, most notably Niall Ferguson, argue that Britain chose France and Russia over Germany because Germany was too weak an ally to provide an effective counterbalance to the other powers and could not provide Britain with the imperial security that was achieved by the Entente agreements.[21] In the words of the British diplomat Arthur Nicolson, it was "far more disadvantageous to us to have an unfriendly France and Russia than an unfriendly Germany."[22] Ferguson argues that the British government rejected German alliance overtures "not because Germany began to pose a threat to Britain, but, on the contrary because they realized she did not pose a threat."[23] The impact of the Triple Entente was therefore twofold by improving British relations with France and its ally, Russia, and showing the importance to Britain of good relations with Germany. It was "not that antagonism toward Germany caused its isolation, but rather that the new system itself channeled and intensified hostility towards the German Empire."[24]

The Triple Entente between Britain, France, and Russia is often compared to the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria–Hungary and Italy, but historians caution against that comparison as simplistic. The Entente, in contrast to the Triple Alliance and the Franco-Russian Alliance, was not an alliance of mutual defence and so Britain felt free to make its own foreign policy decisions in 1914. As the British Foreign Office official Eyre Crowe minuted: "The fundamental fact of course is that the Entente is not an alliance. For purposes of ultimate emergencies it may be found to have no substance at all. For the Entente is nothing more than a frame of mind, a view of general policy which is shared by the governments of two countries, but which may be, or become, so vague as to lose all content."[25]

A series of diplomatic incidents between 1905 and 1914 heightened tensions between the Great Powers and reinforced the existing alignments, beginning with the First Moroccan Crisis.

First Moroccan Crisis, 1905–06: Strengthening the Entente[]

The First Moroccan Crisis was an international dispute between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. The crisis worsened German relations with both France and Britain, and helped ensure the success of the new Entente Cordiale. In the words of the historian Christopher Clark, "The Anglo-French Entente was strengthened rather than weakened by the German challenge to France in Morocco."[26]

Bosnian Crisis, 1908: Worsening relations of Russia and Serbia with Austria-Hungary[]

In 1908, Austria-Hungary announced its annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, provinces in the Balkans. Bosnia and Herzegovina had been nominally under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire but administered by Austria-Hungary since the Congress of Berlin in 1878. The announcement upset the fragile balance of power in the Balkans and enraged Serbia and pan-Slavic nationalists throughout Europe. The weakened Russia was forced to submit to its humiliation, but its foreign office still viewed Austria-Hungary's actions as overly aggressive and threatening. Russia's response was to encourage pro-Russian and anti-Austrian sentiment in Serbia and other Balkan provinces, provoking Austrian fears of Slavic expansionism in the region.[27]

Agadir crisis in Morocco, 1911[]

Imperial rivalries pushed France, Germany, and Britain to compete for control of Morocco, leading to a short-lived war scare in 1911. In the end, France established a protectorate over Morocco that increased European tensions. The Agadir Crisis resulted from the deployment of a substantial force of French troops into the interior of Morocco in April 1911. Germany reacted by sending the gunboat SMS Panther to the Moroccan port of Agadir on 1 July 1911. The main result was deeper suspicion between London and Berlin and closer military ties between London and Paris.[28][29]

British backing of France during the crisis reinforced the Entente between the two countries and with Russia, increased Anglo-German estrangement, and deepened the divisions that would erupt in 1914.[30] In terms of internal British jousting, the crisis was part of a five-year struggle inside the British cabinet between Radical isolationists and the Liberal Party's imperialist interventionists. The interventionists sought to use the Triple Entente to contain German expansion. The Radical isolationistss obtained an agreement for official cabinet approval of all initiatives that might lead to war. However, the interventionists were joined by the two leading Radicals, David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. Lloyd George's famous Mansion House speech of 21 July 1911 angered the Germans and encouraged the French.[31]

The crisis led British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey, a Liberal, and French leaders to make a secret naval agreement by which the Royal Navy would protect the northern coast of France from German attack, and France agreed to concentrate the French Navy in the western Mediterranean and to protect British interests there. France was thus able to guard its communications with its North African colonies, and Britain to concentrate more force in home waters to oppose the German High Seas Fleet. The British cabinet was not informed of the agreement until August 1914. Meanwhile, the episode strengthened the hand of German Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who was calling for a greatly-increased navy and obtained it in 1912.[32]

The American historian Raymond James Sontag argues that Agadir was a comedy of errors that became a tragic prelude to the World War I:

- The crisis seems comic--its obscure origin, the questions at stake, the conduct of the actors--had comic. The results were tragic. Tension between France and Germany and between Germany and England have been increased; the armaments race receive new impetus; the conviction that an early war was inevitable spread through the governing class of Europe.[33]

Italo-Turkish War: Isolation of the Ottomans, 1911–1912[]

In the Italo-Turkish War, Italy defeated the Ottoman Empire in North Africa in 1911–1912.[34] Italy easily captured the important coastal cities, but its army failed to advance far into the interior. Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet, a province whose most notable subprovinces, or sanjaks, were Fezzan, Cyrenaica, and Tripoli itself. The territories together formed what was later known as Italian Libya. The main significance for the World War I was that it was now clear that no Great Power still appeared to wish to support the Ottoman Empire, which paved the way for the Balkan Wars. Christopher Clark stated, "Italy launched a war of conquest on an African province of the Ottoman Empire, triggering a chain of opportunistic assaults on Ottoman territories across the Balkans. The system of geographical balances that had enabled local conflicts to be contained was swept away." [35]

Balkan Wars, 1912–13: Growth of Serbian and Russian power[]

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkan Peninsula in southeastern Europe in 1912 and 1913. Four Balkan states defeated the Ottoman Empire in the first war; one of them, Bulgaria, was defeated in the second war. The Ottoman Empire lost nearly all of its territory in Europe. Austria-Hungary, although not a combatant, was weakened, as a much-enlarged Serbia pushed for union of all South Slavs.

The Balkan Wars in 1912–1913 increased international tension between Russia and Austria-Hungary. It also led to a strengthening of Serbia and a weakening of the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, which might otherwise have kept Serbia under control, thus disrupting the balance of power in Europe toward Russia.

Russia initially agreed to avoid territorial changes, but later in 1912, it supported Serbia's demand for an Albanian port. The London Conference of 1912–13 agreed to create an independent Albania, but both Serbia and Montenegro refused to comply. After an Austrian and then an international naval demonstration in early 1912 and Russia's withdrawal of support, Serbia backed down. Montenegro was not as compliant, and on May 2, the Austrian council of ministers met and decided to give Montenegro a last chance to comply, or it would resort to military action. However, seeing the Austro-Hungarian military preparations, the Montenegrins requested for the ultimatum to be delayed, and they complied.[36]

The Serbian government, having failed to get Albania, now demanded for the other spoils of the First Balkan War to be reapportioned, and Russia failed to pressure Serbia to back down. Serbia and Greece allied against Bulgaria, which responded with a pre-emptive strike against their forces and so began the Second Balkan War.[37] The Bulgarian army crumbled quickly after the Ottoman Empire and Romania joined the war.

The Balkan Wars strained the German alliance with Austria-Hungary. The attitude of the German government to Austro-Hungarian requests of support against Serbia was initially divided and inconsistent. After the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912, it was clear that Germany was not ready to support Austria-Hungary in a war against Serbia and its likely allies.

In addition, German diplomacy before, during, and after the Second Balkan War was pro-Greek and pro-Romanian and against Austria-Hungary's increasing pro-Bulgarian sympathies. The result was tremendous damage to relations between both empires. Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold von Berchtold remarked to the German ambassador, Heinrich von Tschirschky in July 1913, "Austria-Hungary might as well belong 'to the other grouping' for all the good Berlin had been."[38]

In September 1913, it was learned that Serbia was moving into Albania, and Russia was doing nothing to restrain it, and the Serbian government would not guarantee to respect Albania's territorial integrity and suggested that some frontier modifications would occur. In October 1913, the council of ministers decided to send Serbia a warning followed by an ultimatum for Germany and Italy to be notified of some action and asked for support and for spies to be sent to report if there was an actual withdrawal. Serbia responded to the warning with defiance, and the ultimatum was dispatched on October 17 and received the following day. It demanded for Serbia to evacuate from Albania within eight days. After Serbia complied, the Kaiser made a congratulatory visit to Vienna to try to fix some of the damage done earlier in the year.[39]

By then, Russia had mostly recovered from its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, and the calculations of Germany and Austria were driven by a fear that Russia would eventually become too strong to be challenged. The conclusion was that any war with Russia had to occur within the next few years to have any chance of success.[40]

Franco-Russian Alliance changes to Balkan inception scenario, 1911–1913[]

The original Franco-Russian alliance was formed to protect both France and Russia from a German attack. In the event of such an attack, both states would mobilize in tandem, placing Germany under the threat of a two-front war. However, there were limits placed on the alliance so that it was essentially defensive in character.

Throughout the 1890s and the 1900s, the French and the Russians made clear the limits of the alliance did not extend to provocations caused by each other's adventurous foreign policy. For example, Russia warned France that the alliance would not operate if the French provoked the Germans in North Africa. Equally, the French insisted that the Russians should not use the alliance to provoke Austria-Hungary or Germany in the Balkans and that France did not recognise in the Balkans a vital strategic interest for France or Russia.

That changed in the last 18 to 24 months before the outbreak of the war. At the end of 1911, particularly during the Balkan Wars in 1912–1913, the French view changed to accept the importance of the Balkans to Russia. Moreover, France clearly stated that if, as a result of a conflict in the Balkans, war broke out between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, France would stand by Russia. Thus, the alliance changed in character and Serbia now became a security salient for Russia and France. A war of Balkan inception, regardless of who started such a war, would cause the alliance would respond by viewing the conflict as a casus foederis, a trigger for the alliance. Christopher Clark described that change as "a very important development in the pre-war system which made the events of 1914 possible."[41] Otte also agrees that France became significantly less keen on restraining Russia after the Austro-Serbian crisis of 1912, and sought to embolden Russia against Austria. The Russian ambassador conveyed Poincare's message as saying that "if Russia wages war, France also wages war."[42]

Liman von Sanders Affair: 1913-14[]

This was a crisis caused by the appointment of a German officer, Liman von Sanders, to command the Ottoman First Army Corps guarding Constantinople and the subsequent Russian objections. In November, 1913, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov complained to Berlin that the Sanders mission was an "openly hostile act." In addition to threatening Russia's foreign trade, half of which flowed through the Turkish Straits, the mission raised the possibility of a German-led Ottoman assault on Russia's Black Sea ports, and it imperiled Russian plans for expansion in eastern Anatolia. A compromise arrangement was agreed for Sanders to be appointed to the rather less senior and less influential position of Inspector General in January 1914.[43] When the war came Sanders provided only limited help to the Ottoman forces.[44]

Anglo-German détente, 1912–14[]

Historians have cautioned that taken together, the preceding crises should not be seen as an argument that a European war was inevitable in 1914.

Significantly, the Anglo-German naval arms race had been over by 1912. In April 1913, Britain and Germany signed an agreement over the African territories of the Portuguese Empire, which was expected to collapse imminently. Moreover, the Russians were threatening British interests in Persia and India to the extent that in 1914, there were signs that the British were cooling in their relations with Russia and that an understanding with Germany might be useful. The British were "deeply annoyed by St Petersburg's failure to observe the terms of the agreement struck in 1907 and began to feel an arrangement of some kind with Germany might serve as a useful corrective."[22] Despite the infamous 1908 interview in The Daily Telegraph, which implied that Kaiser Wilhelm wanted war, he came to be regarded as a guardian of peace. After the Moroccan Crisis, the Anglo-German press wars, previously an important feature of international politics during the first decade of the century, virtually ceased. In early 1913, H. H. Asquith stated, "Public opinion in both countries seems to point to an intimate and friendly understanding." The end of the naval arms race, the relaxation of colonial rivalries, and the increased diplomatic co-operation in the Balkans all resulted in an improvement in Germany's image in Britain by the eve of the war.[45]

The British diplomat Arthur Nicolson wrote in May 1914, "Since I have been at the Foreign Office I have not seen such calm waters."[46] The Anglophile German Ambassador Karl Max, Prince Lichnowsky, deplored that Germany had acted hastily without waiting for the British offer of mediation in July 1914 to be given a chance.

July Crisis: The chain of events[]

Full article: July Crisis

- June 28, 1914: Serbian irredentists assassinate Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

- June 30: Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Count Leopold Berchtold and Emperor Franz Josef agree that the "policy of patience" with Serbia had to end, and a firm line must be taken.

- July 5: The Austro-Hungarian diplomat Alexander, Count of Hoyos, visits Berlin to ascertain German attitudes.

- July 6: Germany provides unconditional support to Austria-Hungary, the so-called "blank cheque.".

- July 20–23: French President Raymond Poincaré, on a state visit to the Tsar at St. Petersburg, urges an intransigent opposition to any Austro-Hungarian measure against Serbia.

- July 23: Austria-Hungary, following its own secret enquiry, sends an ultimatum to Serbia containing their demands and giving only 48 hours to comply.

- July 24: Sir Edward Grey, speaking for the British government, asks that Germany, France, Italy and Britain, "who had no direct interests in Serbia, should act together for the sake of peace simultaneously."[47]

- July 24: Serbia seeks support from Russia, which advises Serbia not to accept the ultimatum.[48] Germany officially declares support for Austria-Hungary's position.

- July 24: The Russian Council of Ministers agrees to a secret partial mobilization of the Russian Army and Navy.[citation needed]

- July 25: The Russian Tsar approves the Council of Ministers decision, and Russia begins the partial mobilization of 1.1 million men against Austria-Hungary.[49]

- July 25: Serbia responds to the Austro-Hungarian démarche with less than full acceptance and asks for the Hague Tribunal to arbitrate. Austria-Hungary breaks diplomatic relations with Serbia, which mobilizes its army.

- July 26: Serbian reservists accidentally violate the Austro-Hungarian border at Temes-Kubin.[50]

- July 26: A meeting is organised to take place between ambassadors from Britain, Germany, Italy and France to discuss the crisis. Germany declines the invitation.

- July 28: Austria-Hungary, having failed to accept Serbia's response on the 25th, declares war on Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian mobilisation against Serbia begins.

- July 29: Sir Edward Grey appeals to Germany to intervene to maintain peace.

- July 29: The British ambassador in Berlin, Sir Edward Goschen, is informed by the German Chancellor that Germany is contemplating war with France and wishes to send its army through Belgium. He tries to secure Britain's neutrality in such an action.

- July 29: In the morning, the Russian general mobilisation against Austria-Hungary and Germany is ordered; in the evening,[51] the Tsar opts for partial mobilization after a flurry of telegrams with Kaiser Wilhelm.[52]

- July 30: The Russian general mobilization is reordered by the Tsar on the instigation of Sergei Sazonov.

- July 31: The Austro-Hungarian general mobilization is ordered.

- July 31: Germany enters a period preparatory to war and sends an ultimatum to Russia, demanding a halt to general mobilization within twelve hours, but Russia refuses.

- July 31: Both France and Germany are asked by Britain to declare their support for the ongoing neutrality of Belgium. France agrees, but Germany does not respond.

- July 31: Germany asks France if it would stay neutral in case of a war between Germany and Russia.

- August 1: The German general mobilization is ordered, and the Aufmarsch II West deployment is chosen.

- August 1: The French general mobilization is ordered, and Plan XVII chosen for deployment.

- August 1: Germany declares war against Russia.

- August 1: The Tsar responds to the Kaiser's telegram by stating, "I would gladly have accepted your proposals had not the German ambassador this afternoon presented a note to my Government declaring war."

- August 2: Germany and the Ottoman Empire sign a secret treaty[53] that entrenches the Ottoman–German Alliance.

- August 3: France declines (See Note[citation needed]) Germany's demand to remain neutral.[54]

- August 3: Germany declares war on France and states to Belgium that it would "treat her as an enemy" if it did not allow free passage of German troops across her lands.

- August 4: Germany implements an offensive operation inspired by Schlieffen Plan.

- August 4 (midnight): Having failed to receive notice from Germany assuring the neutrality of Belgium, Britain declares war on Germany.

- August 6: Austria-Hungary declares war on Russia.

- August 23: Japan, honoring the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, declares war on Germany.

- August 25: Japan declares war on Austria-Hungary.

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Serbian irredentists, 28 June 1914[]

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, are shot dead by two gun shots[56] in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, one of a group of six assassins (five Serbs and one Bosniak) co-ordinated by Danilo Ilić, a Bosnian Serb and a member of the Black Hand secret society.

The assassination is significant because it was perceived by Austria-Hungary as an existential challenge and so was viewed as providing a casus belli with Serbia. Emperor Franz Josef was 84 and so the assassination of his heir, so soon before he was likely to hand over the crown, was seen as a direct challenge to the empire. Many ministers in Austria, especially Berchtold, argue that the act must be avenged.[57] Moreover, the Archduke had been a decisive voice for peace in the previous years but was now removed from the discussions. The assassination triggered the July Crisis, which turned a local conflict into a European and later a world war.

Austria edges towards war with Serbia[]

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, sent deep shockwaves throughout the empire's elites and has been described as a "9/11 effect, a terrorist event charged with historic meaning, transforming the political chemistry in Vienna." It gave free rein to elements clamoring for war with Serbia, especially in the army.[58]

It quickly emerged that three leading members of the assassination squad had spent long periods of time in Belgrade, only recently crossed the border from Serbia, and carried weapons and bombs of Serbian manufacture. They were secretly sponsored by the Black Hand, whose objectives included the liberation of all Bosnian Slavs from imperial rule, and they had been masterminded by the Head of Serbian military intelligence, Dragutin Dimitrijević, also known as Apis.

Two days after the assassination, Foreign Minister Berchtold and the Emperor agreed that the "policy of patience" with Serbia had to end. Austria-Hungary feared that if it displayed weakness, its neighbours to the south and the east would be emboldened, but war with Serbia would put to an end the problems experienced with Serbia. Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf stated about Serbia, "If you have a poisonous adder at your heel, you stamp on its head, you don't wait for the bite."[58]

There was also a feeling that the moral effects of military action would breathe new life into the exhausted structures of the Habsburgs by restoring the vigour and virility of an imagined past and that Serbia must be dealt with before it became too powerful to defeat militarily.[59] The principal voices for peace in previous years had included Franz Ferdinand himself. His removal not only provided the casus belli but also removed one of the most prominent doves from policymaking.

Since taking on Serbia involved the risk of war with Russia, Vienna sought the views of Berlin. Germany provided unconditional support for war with Serbia in the so-called "blank cheque." Buoyed up by German support, Austria-Hungary began drawing up an ultimatum, giving the Serbs forty-eight hours to respond to ten demands. It was hoped that the ultimatum would be rejected to provide the pretext for war with a neighbor that was considered to be impossibly turbulent.

Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., has emphasized the role of Austria-Hungary in starting the war. Convinced that Serbian nationalism and Russian Balkan ambitions were disintegrating the empire, Austria-Hungary hoped for a limited war against Serbia and that strong German support would force Russia to keep out of the war and to weaken its prestige in the Balkans.[60]

Austria-Hungary remained fixated on Serbia but did not decide on its precise objectives other than eliminating the threat from Serbia. Worst of all, events soon revealed that Austria-Hungary's top military commander had failed to grasp Russia's military recovery since its defeat by Japan; its enhanced ability to mobilize relatively quickly; and not least, the resilience and strength of the Serbian Army.[58]

Nevertheless, having decided upon war with German support, Austria-Hungary was slow to act publicly and did not deliver the ultimatum until July 23, some three weeks after the assassinations on 28 June. Thus, it lost the reflex sympathies attendant to the Sarajevo murders and gave the further impression to the Entente powers of using the assassinations only as pretexts for aggression.[61]

"Blank cheque" of German support to Austria-Hungary, 6 July[]

On July 6, Germany provided its unconditional support to Austria-Hungary's quarrel with Serbia in the so-called "blank cheque." In response to a request for support, Vienna was told the Kaiser's position was that if Austria-Hungary "recognised the necessity of taking military measures against Serbia he would deplore our not taking advantage of the present moment which is so favourable to us... we might in this case, as in all others, rely upon German support."[62][63]

The thinking was that since Austria-Hungary was Germany's only ally, if the former's prestige was not restored, its position in the Balkans might be irreparably damaged and encourage further irredentism by Serbia and Romania.[64] A quick war against Serbia would not only eliminate it but also probably lead to further diplomatic gains in Bulgaria and Romania. A Serbian defeat would also be a defeat for Russia and reduce its influence in the Balkans.

The benefits were clear but there were risks that Russia would intervene and lead to a continental war. However, that was thought even more unlikely since Russia had not yet finished its French-funded rearmament programme, which was scheduled for completion in 1917. Moreover, it was not believed that Russia, as an absolute monarchy, would support regicides and, more broadly, "the mood across Europe was so anti-Serbian that even Russia would not intervene." Personal factors also weighed heavily since the German Kaiser was close to the murdered Franz Ferdinand and was so affected by his death that German counsels of restraint toward Serbia in 1913 changed to an aggressive stance.[65]

On the other hand, the military thought that if Russia intervened, St. Petersburg clearly desired war, and now would be a better time to fight since Germany had a guaranteed ally in Austria-Hungary, Russia was not ready and Europe was sympathetic. On balance, at that point, the Germans anticipated that their support would mean the war would be a localised affair between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, particularly if Austria moved quickly "while the other European powers were still disgusted over the assassinations and therefore likely to be sympathetic to any action Austria-Hungary took."[66]

France backs Russia, 20–23 July[]

French president Raymond Poincaré arrived in St. Petersburg for a prescheduled state visit on 20 July and departed on 23 July. The French and the Russians agreed their alliance extended to supporting Serbia against Austria, confirming the pre-established policy behind the Balkan inception scenario. As Christopher Clark noted, "Poincare had come to preach the gospel of firmness and his words had fallen on ready ears. Firmness in this context meant an intransigent opposition to any Austrian measure against Serbia. At no point do the sources suggest that Poincare or his Russian interlocutors gave any thought whatsoever to what measures Austria-Hungary might legitimately be entitled to take in the aftermath of the assassinations."[67]

On 21 July, the Russian Foreign Minister warned the German ambassador to Russia, "Russia would not be able to tolerate Austria-Hungary's using threatening language to Serbia or taking military measures." The leaders in Berlin discounted the threat of war. German Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow noted that "there is certain to be some blustering in St. Petersburg". German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg told his assistant that Britain and France did not realise that Germany would go to war if Russia mobilised. He thought that London saw a German "bluff" and was responding with a "counterbluff."[68] The political scientist James Fearon argued that the Germans believed Russia to be expressing greater verbal support for Serbia than it would actually provide to pressure Germany and Austria-Hungary to accept some of the Russian demands in negotiations. Meanwhile, Berlin downplayed its actual strong support for Vienna to avoid appearing the aggressor and thus alienate German socialists.[69]

Austria-Hungary presents ultimatum to Serbia, 23 July[]

On 23 July, Austria-Hungary, following its own enquiry into the assassinations, sent an ultimatum [1] to Serbia, containing their demands and giving 48 hours to comply.

Russia mobilises and crisis escalates, 24–25 July[]

On 24–25 July, the Russian Council of Ministers met at Yelagin Palace[70] and, in response to the crisis and despite the fact that Russia had no alliance with Serbia, it agreed to a secret partial mobilisation of over one million men of the Russian Army and the Baltic and Black Sea Fleets. It is worth stressing since it is a cause of some confusion in general narratives of the war that Russia acted before Serbia had rejected the ultimatum, Austria-Hungary had declared war on 28 July, or any military measures had been taken by Germany. The move had limited diplomatic value since the Russians did not make their mobilisation public until 28 July.

These arguments used to support the move in the Council of Ministers:

- The crisis was being used as a pretext by Germany to increase its power.

- Acceptance of the ultimatum would mean that Serbia would become a protectorate of Austria-Hungary.

- Russia had backed down in the past, such as in the Liman von Sanders affair and the Bosnian Crisis, but it had only encouraged the Germans.

- Russian arms had recovered sufficiently since the disaster in the Russo-Japanese War.

In addition, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov believed that war was inevitable and refused to acknowledge that Austria-Hungary had a right to counter measures in the face of Serbian irredentism. On the contrary, Sazonov had aligned himself with the irredentism and expected the collapse of Austria-Hungary. Crucially, the French had provided clear support for their Russian ally for a robust response in their recent state visit only days earlier. Also in the background was Russian anxiety of the future of the Turkish Straits, "where Russian control of the Balkans would place Saint Petersburg in a far better position to prevent unwanted intrusions on the Bosphorus."[71]

The policy was intended to be a mobilization against Austria-Hungary only. However, incompetence made the Russians realise by 29 July that partial mobilization was not militarily possible but would interfere with general mobilization. The Russians moved to full mobilization on 30 July as the only way to allow the entire operation to succeed.

Christopher Clark stated, "It would be difficult to overstate the historical importance of the meetings of 24 and 25 July."[72]

"In taking these steps, [Russian Foreign Minister] Sazonov and his colleagues escalated the crisis and greatly increased the likelihood of a general European war. For one thing, Russian premobilisation altered the political chemistry in Serbia, making it unthinkable that the Belgrade government, which had originally given serious consideration to accepting the ultimatum, would back down in the face of Austrian pressure. It heightened the domestic pressure on the Russian administration... it sounded alarm bells in Austria-Hungary. Most importantly of all, these measures drastically raised the pressure on Germany, which had so far abstained from military preparations and was still counting on the localisation of the Austro-Serbian conflict."[73]

Serbia rejects the ultimatum and Austria declares war on Serbia 25–28 July[]

Serbia initially considered accepting all the terms of the Austrian ultimatum before news from Russia of premobilisation measures stiffened its resolve.[74]

The Serbs drafted their reply to the ultimatum in such a way as to give the impression of making significant concessions. However, as Clark stated, "In reality, then, this was a highly perfumed rejection on most points."[75] In response to the rejection of the ultimatum, Austria-Hungary immediately broke off diplomatic relations on 25 July and declared war on 28 July.

Russian general mobilisation is ordered, 29–30 July[]

On July 29, 1914, the Tsar ordered full mobilisation but changed his mind after receiving a telegram from Kaiser Wilhelm and ordered partial mobilisation instead. The next day, Sazonov once more persuaded Nicholas of the need for general mobilization, and the order was issued on the same day.

Clark stated, "The Russian general mobilisation was one of the most momentous decisions of the[clarification needed] July crisis. This was the first of the general mobilisations. It came at the moment when the German government had not yet even declared the State of Impending War."[76]

Russia did so for several reasons:

- Austria-Hungary had declared war on 28 July.

- The previously-ordered partial mobilization was incompatible with a future general mobilization.

- Sazonov's conviction that Austrian intransigence was German policy and so there was no longer any point in mobilising against only Austria-Hungary.

- France reiterated its support for Russia, and there was significant cause to think that Britain would also support Russia.[77]

German mobilisation and war with Russia and France, 1–3 August[]

On 28 July, Germany learned through its spy network that Russia had implemented its "Period Preparatory to War."[citation needed] Germany assumed that Russia had finally decided upon war and that its mobilisation put Germany in danger,[citation needed] especially since German war plans, the so-called Schlieffen Plan, relied upon Germany to mobilise speedily enough to defeat France first by attacking largely through neutral Belgium before the Germans turned to defeat the slower-moving Russians.

Clark states, "German efforts at mediation – which suggested that Austria should 'Halt in Belgrade' and use the occupation of the Serbian capital to ensure its terms were met – were rendered futile by the speed of Russian preparations, which threatened to force the Germans to take counter–measures before mediation could begin to take effect."[78]

Thus, in response to Russian mobilisation,[citation needed] Germany ordered the state of Imminent Danger of War on 31 July, and when the Russians refused to rescind their mobilization order, Germany mobilized and declared war on Russia on 1 August. The Franco-Russian Alliance meant that countermeasures by France were correctly assumed to be inevitable by Germany, which declared war on France on 3 August 1914.

Britain declares war on Germany, 4 August 1914[]

After the German invasion of neutral Belgium, Britain issued an ultimatum to Germany on 2 August to withdraw or face war. The Germans did not comply and so Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914.

Britain's reasons for declaring war were complex. The ostensible reason given was that Britain was required to safeguard Belgium's neutrality under the Treaty of London (1839). According to Isabel V. Hull :

- Annika Mombauer correctly sums up the current historiography: "Few historians would still maintain that the 'rape of Belgium was the real motive for Britain's declaration of war on Germany." Instead, the role of Belgian neutrality is variously interpreted as an excuse to mobilize the public, to provide embarrassed radicals in the cabinet with the justification for abandoning the principal pacifism and thus were staying in office, or in the more conspiratorial versions to cover for naked imperial interests.[79]

The German invasion of Belgium legitimised and galvanised popular support for the war, especially among pacifistic Liberals. The strategic risk posed by German control of the Belgian and ultimately the French coast was unacceptable. Britain's relationship with its Entente partner France was critical. Edward Grey argued that the secret naval agreements with France, despite not having been approved by the Cabinet, created a moral obligation between Britain and France.[80] If Britain abandoned its Entente friends, whether Germany won the war or the Entente won without British support would leave Britain without any friends. That would leave both Britain and its empire vulnerable to attack.[80]

The British Foreign Office mandarin Eyre Crowe stated: "Should the war come, and England stand aside, one of two things must happen. (a) Either Germany and Austria win, crush France and humiliate Russia. What will be the position of a friendless England? (b) Or France and Russia win. What would be their attitude towards England? What about India and the Mediterranean?" [80]

Domestically, the Liberal Cabinet was split, and if war was not declared the government would fall, as the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, as well as Edward Grey and Winston Churchill, made it clear that they would resign. In that event, the existing Liberal Cabinet would fall since it was likely that the pro-war Conservatives would come to power, which would still lead to a British entry into the war, only slightly later. The wavering Cabinet ministers were also likely motivated by the desire to avoid senselessly splitting their party and sacrificing their jobs.[81]

On the diplomatic front, the European powers began to publish selected, and sometimes misleading, compendia of diplomatic correspondence, seeking to establish justification for their own entry into the war, and cast blame on other actors for the outbreak of war.[82] First of these color books to appear, was the German White Book[83] which appeared on the same day as Britain's war declaration.[84]

Domestic political factors[]

German domestic politics[]

Left-wing parties, especially the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), made large gains in the 1912 German election. The German government was still dominated by the Prussian Junkers, who feared the rise of left-wing parties. Fritz Fischer famously argued that they deliberately sought an external war to distract the population and to whip up patriotic support for the government.[85] Indeed, one German military leader, Moritz von Lynker, the chief of the military cabinet, wanted war in 1909 because it was "desirable in order to escape from difficulties at home and abroad."[86] The Conservative Party leader Ernst von Heydebrand und der Lasa suggested that "a war would strengthen patriarchal order."[87]

Other authors argue that German conservatives were ambivalent about a war for fear that losing a war would have disastrous consequences and believed that even a successful war might alienate the population if it was lengthy or difficult.[21] Scenes of mass "war euphoria" were often doctored for propaganda purposes, and even the scenes which were genuine would reflect the general population. Many German people complained of a need to conform to the euphoria around them, which allowed later Nazi propagandists to "foster an image of national fulfillment later destroyed by wartime betrayal and subversion culminating in the alleged Dolchstoss (stab in the back) of the army by socialists."[88]

Drivers of Austro-Hungarian policy[]

The argument that Austria-Hungary was a moribund political entity, whose disappearance was only a matter of time, was deployed by hostile contemporaries to suggest that its efforts to defend its integrity during the last years before the war were, in some sense, illegitimate.[89]

Clark states, "Evaluating the prospects of the Austro-Hungarian empire on the eve of the first world war confronts us in an acute way with the problem of temporal perspective.... The collapse of the empire amid war and defeat in 1918 impressed itself upon the retrospective view of the Habsburg lands, overshadowing the scene with auguries of imminent and ineluctable decline."[90]

It is true that Austro-Hungarian politics in the decades before the war were increasingly dominated by the struggle for national rights among the empire's eleven official nationalities: Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Poles, and Italians. However, before 1914, radical nationalists seeking full separation from the empire were still a small minority, and Austria-Hungary's political turbulence was more noisy than deep.[citation needed]

In fact, in the decade before the war, the Habsburg lands passed through a phase of strong widely-shared economic growth. Most inhabitants associated the Habsburgs with the benefits of orderly government, public education, welfare, sanitation, the rule of law, and the maintenance of a sophisticated infrastructure.

Christopher Clark states: "Prosperous and relatively well administered, the empire, like its elderly sovereign, exhibited a curious stability amid turmoil. Crises came and went without appearing to threaten the existence of the system as such. The situation was always, as the Viennese journalist Karl Kraus quipped, 'desperate but not serious'."[91]

Jack Levy and William Mulligan argue that the death of Franz Ferdinand itself was a significant factor in helping escalate the July Crisis into a war by killing a powerful proponent for peace and thus encouraged a more belligerent decision-making process.[92]

Drivers of Serbian policy[]

The principal aims of Serbian policy were to consolidate the Russian-backed expansion of Serbia in the Balkan Wars and to achieve dreams of a Greater Serbia, which included the unification of lands with large ethnic Serb populations in Austria-Hungary, including Bosnia [93]

Underlying that was a culture of extreme nationalism and a cult of assassination, which romanticized the slaying of the Ottoman sultan as the heroic epilogue to the otherwise-disastrous Battle of Kosovo on 28 June 1389. Clark states: "The Greater Serbian vision was not just a question of government policy, however, or even of propaganda. It was woven deeply into the culture and identity of the Serbs."[93]

Serbian policy was complicated by the fact that the main actors in 1914 were both the official Serb government, led by Nikola Pašić, and the "Black Hand" terrorists, led by the head of Serb military intelligence, known as Apis. The Black Hand believed that a Greater Serbia would be achieved by provoking a war with Austria-Hungary by an act of terror. The war would be won with Russian backing.

The official government position was to focus on consolidating the gains made during the exhausting Balkan War and to avoid further conflicts. That official policy was temporized by the political necessity of simultaneously and clandestinely supporting dreams of a Greater Serbian state in the long term.[94] The Serbian government found it impossible to put an end to the machinations of the Black Hand for fear it would itself be overthrown. Clark states: "Serbian authorities were partly unwilling and partly unable to suppress the irredentist activity that had given rise to the assassinations in the first place".[95]

Russia tended to support Serbia as a fellow Slavic state, considered Serbia its "client," and encouraged Serbia to focus its irredentism against Austria-Hungary because it would discourage conflict between Serbia and Bulgaria, another prospective Russian ally, in Macedonia.

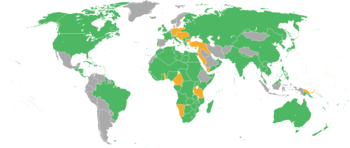

Imperialism[]

Impact of colonial rivalry and aggression on Europe in 1914[]

Imperial rivalry and the consequences of the search for imperial security or for imperial expansion had important consequences for the origins of World War I.

Imperial rivalries between France, Britain, Russia and Germany played an important part in the creation of the Triple Entente and the relative isolation of Germany. Imperial opportunism, in the form of the Italian attack on Ottoman Libyan provinces, also encouraged the Balkan wars of 1912-13, which changed the balance of power in the Balkans to the detriment of Austria-Hungary.

Some historians, such as Margaret MacMillan, believe that Germany created its own diplomatic isolation in Europe, in part by an aggressive and pointless imperial policy known as Weltpolitik. Others, such as Clark, believe that German isolation was the unintended consequence of a détente between Britain, France, and Russia. The détente was driven by Britain's desire for imperial security in relation to France in North Africa and to Russia in Persia and India.

Either way, the isolation was important because it left Germany few options but to ally itself more strongly with Austria-Hungary, leading ultimately to unconditional support for Austria-Hungary's punitive war on Serbia during the July Crisis.

German isolation: a consequence of Weltpolitik?[]

Bismarck disliked the idea of an overseas empire but supported France's colonization in Africa because it diverted the French government, attention, and resources away from Continental Europe and revanchism after 1870. Germany's "New Course" in foreign affairs, Weltpolitik ("world policy"), was adopted in the 1890s after Bismarck's dismissal.

Its aim was ostensibly to transform Germany into a global power through assertive diplomacy, the acquisition of overseas colonies, and the development of a large navy.

Some historians, notably MacMillan and Hew Strachan, believe that a consequence of the policy of Weltpolitik and Germany's associated assertiveness was to isolate it. Weltpolitik, particularly as expressed in Germany's objections to France's growing influence in Morocco in 1904 and 1907, also helped cement the Triple Entente. The Anglo-German naval race also isolated Germany by reinforcing Britain's preference for agreements with Germany's continental rivals: France and Russia.[96]

German isolation: a consequence of the Triple Entente?[]

Historians like Ferguson and Clark believe that Germany's isolation was the unintended consequences of the need for Britain to defend its empire against threats from France and Russia. They also downplay the impact of Weltpolitik and the Anglo-German naval race, which ended in 1911.

Britain and France signed a series of agreements in 1904, which became known as the Entente Cordiale. Most importantly, it granted freedom of action to Britain in Egypt and to France in Morocco. Equally, the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention greatly improved British–Russian relations by solidifying boundaries that identified respective control in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet.

The alignment between Britain, France, and Russia became known as the Triple Entente. However, the Triple Entente was not conceived as a counterweight to the Triple Alliance but as a formula to secure imperial security between the three powers.[97] The impact of the Triple Entente was twofold: improving British relations with France and its ally, Russia, and showing the importance to Britain of good relations with Germany. Clark states it was "not that antagonism toward Germany caused its isolation, but rather that the new system itself channeled and intensified hostility towards the German Empire."[98]

Imperial opportunism[]

The Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912 was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Italy in North Africa. The war made it clear that no great power still appeared to wish to support the Ottoman Empire, which paved the way for the Balkan Wars.

The status of Morocco had been guaranteed by international agreement, and when France attempted a great expansion of its influence there without the assent of all other signatories, Germany opposed and prompted the Moroccan Crises: the Tangier Crisis of 1905 and the Agadir Crisis of 1911. The intent of German policy was to drive a wedge between the British and French, but in both cases, it produced the opposite effect and Germany was isolated diplomatically, most notably by lacking the support of Italy despite it being in the Triple Alliance. The French protectorate over Morocco was established officially in 1912.

In 1914, however, the African scene was peaceful. The continent was almost fully divided up by the imperial powers, with only Liberia and Ethiopia still independent. There were no major disputes there pitting any two European powers against each other.[99]

Marxist interpretation[]

Marxists typically attributed the start of the war to imperialism. "Imperialism," argued Lenin, "is the monopoly stage of capitalism." He thought that monopoly capitalists went to war to control markets and raw materials. Richard Hamilton observed that the argument went that since industrialists and bankers were seeking raw materials, new markets and new investments overseas, if they were blocked by other powers, the "obvious" or "necessary" solution was war.[100]

Hamilton somewhat criticized the view that the war was launched to secure colonies but agreed that while imperialism may have been on the mind of key decision makers. He argued that it was not necessarily for logical, economic reasons. Firstly, the different powers of the war had different imperial holdings. Britain had the largest empire in the world and Russia had the second largest, but France had a modestly-sized empire. Conversely. Germany had a few unprofitable colonies, and Austria-Hungary had no overseas holdings or desire to secure any and so the divergent interests require any "imperialism argument" to be specific in any supposed "interests" or "needs" that decision makers would be trying to meet. None of Germany's colonies made more money than was required to maintain them, and they also were only 0.5% of Germany's overseas trade, and only a few thousand Germans migrated to the colonies. Thus, he argues that colonies were pursued mainly as a sign of German power and prestige, rather than for profit. While Russia eagerly pursued colonisation in East Asia by seizing control of Manchuria, it had little success; the Manchurian population was never sufficiently integrated into the Russian economy and efforts to make Manchuria, a captive trade market did not end Russia's negative trade deficit with China. Hamilton argued that the "imperialism argument" depended upon the view of national elites being informed, rational, and calculating, but it is equally possible to consider that decision-makers were uninformed or ignorant. Hamilton suggested that imperial ambitions may have been driven by groupthink because every other country was doing it. That made policymakers think that their country should do the same (Hamilton noted that Bismarck was famously not moved by such peer pressure and ended Germany's limited imperialist movement and regarded colonial ambitions as a waste of money but simultaneously recommended them to other nations.[101]

Hamilton was more critical of the view that capitalists and business leaders drove the war. He thought that businessmen, bankers, and financiers were generally against the war, as they viewed it as being perilous to economic prosperity. The decision of Austria-Hungary to go to war was made by the monarch, his ministers, and military leaders, with practically no representation from financial and business leaders even though Austria-Hungary was then developing rapidly. Furthermore, evidence can be found from the Austro-Hungarian stock market, which responded to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand with unease but no sense of alarm and only a small decrease in share value. However, when it became clear that war was a possibility, share values dropped sharply, which suggested that investors did not see war as serving their interests. One of the strongest sources of opposition to the war was from major banks, whose financial bourgeoisie regarded the army as the reserve of the aristocracy and utterly foreign to the banking universe. While the banks had ties to arms manufacturers, it was those companies that had links to the military, not the banks, which were pacifistic and profoundly hostile to the prospect of war. However, the banks were largely excluded from the nation's foreign affairs. Likewise, German business leaders had little influence. Hugo Stinnes, a leading German industrialist, advocated peaceful economic development and believed that Germany would be able to rule Europe by economic power and that war would be a disruptive force. Carl Duisberg, a chemical industrialist, hoped for peace and believed that the war would set German economic development back a decade, as Germany's extraordinary prewar growth had depended upon international trade and interdependence. While some bankers and industrialists tried to curb Wilhelm II away from war, their efforts ended in failure. There is no evidence they ever received a direct response from the Kaiser, chancellor, or foreign secretary or that their advice was discussed in depth by the Foreign Office or the General Staff. The German leadership measured power not in financial ledgers but land and military might.[102] In Britain, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lloyd George, had been informed by the Governor of the Bank of England that business and financial interests opposed British intervention in the war. Lord , a leading British banker, called the financial editor at The Times newspaper and insisted for the paper to denounce the war and to advocate for neutrality, but the lead members of the newspaper ultimately decided that the paper should support intervention. The Rothschilds would go on to suffer serious losses in the war that amounted to 23% of its capital. Generally speaking, the European business leaders were in favour of profits and peace allowed for stability and investment opportunities across national borders, but war brought the disruption trade, the confiscation of holdings, and the risk of increased taxation. Even arms manufacturers, the so-called "Merchants of Death," would not necessarily benefit since they could make money selling weapons at home, but they could lose access to foreign markets. Krupp, a major arms manufacturer, started the war with 48 million marks in profits but ended it 148 million marks in debt, and the first year of peace saw further losses of 36 million marks.[103][104]

William Mulligan argues that while economic and political factors were often interdependent, economic factors tended towards peace. Prewar trade wars and financial rivalries never threatened to escalate into conflict. Governments would mobilise bankers and financiers to serve their interests, rather than the reverse. The commercial and financial elite recognised peace as necessary for economic development and used its influence to resolve diplomatic crises. Economic rivalries existed but were framed largely by political concerns. Prior to the war, there were few signs that the international economy for war in the summer of 1914.[105]

Social Darwinism[]

Social Darwinism was a theory of human evolution loosely based on Darwinism that influenced most European intellectuals and strategic thinkers from 1870 to 1914. It emphasised that struggle between nations and "races" was natural and that only the fittest nations deserved to survive.[106] It gave an impetus to German assertiveness as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with France and Britain for world power. German colonial rule in Africa in 1884 to 1914 was an expression of nationalism and moral superiority, which was justified by constructing an image of the natives as "Other." The approach highlighted racist views of mankind. German colonization was characterized by the use of repressive violence in the name of "culture" and "civilisation." Germany's cultural-missionary project boasted that its colonial programmes were humanitarian and educational endeavours. Furthermore, the wide acceptance of Social Darwinism by intellectuals justified Germany's right to acquire colonial territories as a matter of the "survival of the fittest," according to the historian Michael Schubert.[107][108]

The model suggested an explanation of why some ethnic groups, then called "races," had been for so long antagonistic, such as Germans and Slavs. They were natural rivals, destined to clash. Senior German generals like Helmuth von Moltke the Younger talked in apocalyptic terms about the need for Germans to fight for their existence as a people and culture. MacMillan states: "Reflecting the Social Darwinist theories of the era, many Germans saw Slavs, especially Russia, as the natural opponent of the Teutonic races."[109] Also, the chief of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff declared: "A people that lays down its weapons seals its fate."[109] In July 1914, the Austrian press described Serbia and the South Slavs in terms that owed much to Social Darwinism.[109] In 1914, the German economist Johann Plenge described the war as a clash between the German "ideas of 1914" (duty, order, justice) and the French "ideas of 1789" (liberty, equality, fraternity).[110] William Mulligen argues that Anglo-German antagonism was also about a clash of two political cultures as well as more traditional geopolitical and military concerns. Britain admired Germany for its economic successes and social welfare provision but also regarded Germany as illiberal, militaristic, and technocratic.[111]

War was seen as a natural and viable or even useful instrument of policy. "War was compared to a tonic for a sick patient or a life-saving operation to cut out diseased flesh."[109] Since war was natural for some leaders, it was simply a question of timing and so it would be better to have a war when the circumstances were most propitious. "I consider a war inevitable," declared Moltke in 1912. "The sooner the better."[112] In German ruling circles, war was viewed as the only way to rejuvenate Germany. Russia was viewed as growing stronger every day, and it was believed that Germany had to strike while it still could before it was crushed by Russia.[113]

Nationalism made war a competition between peoples, nations or races, rather than kings and elites.[114] Social Darwinism carried a sense of inevitability to conflict and downplayed the use of diplomacy or international agreements to end warfare. It tended to glorify warfare, the taking of initiative, and the warrior male role.[115]

Social Darwinism played an important role across Europe, but J. Leslie has argued that it played a critical and immediate role in the strategic thinking of some important hawkish members of the Austro-Hungarian government.[116] Social Darwinism, therefore, normalized war as an instrument of policy and justified its use.

Web of alliances[]

Although general narratives of the war tend to emphasize the importance of alliances in binding the major powers to act in the event of a crisis such as the July Crisis, historians such as Margaret MacMillan warn against the argument that alliances forced the Great Powers to act as they did: "What we tend to think of as fixed alliances before the First World War were nothing of the sort. They were much more loose, much more porous, much more capable of change."[117]

The most important alliances in Europe required participants to agree to collective defence if they were attacked. Some represented formal alliances, but the Triple Entente represented only a frame of mind:

- (1879) or Dual Alliance

- The Franco-Russian Alliance (1894)

- The addition of Italy to the Germany and Austrian alliance in 1882, forming the Triple Alliance

- Treaty of London, 1839, guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium

There are three notable exceptions that demonstrate that alliances did not in themselves force the great powers to act:

- The Entente Cordiale between Britain and France in 1905 included a secret agreement that left the northern coast of France and the Channel to be defended by the British Navy, and the separate "entente" between Britain and Russia (1907) formed the so-called Triple Entente. However, the Triple Entente did not, in fact, force Britain to mobilise because it was not a military treaty.

- Moreover, general narratives of the war regularly misstate that Russia was allied to Serbia. Clive Ponting noted: "Russia had no treaty of alliance with Serbia and was under no obligation to support it diplomatically, let alone go to its defence."[118]

- Italy, despite being part of the Triple Alliance, did not enter the war to defend the Triple Alliance partners.

Arms race[]

By the 1870s or the 1880s, all the major powers were preparing for a large-scale war although none expected one.[119] Britain ignored its small army and focused on building up the Royal Navy, which was already stronger than the next two navies combined. Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Russia, and some smaller countries set up conscription systems in which young men would serve from one to three years in the army and then spend the next twenty years or so in the reserves with annual summer training. Men from higher social statuses became officers. Each country devised a mobilization system in which the reserves could be called up quickly and sent to key points by rail.

Every year, the plans were updated and expanded in terms of complexity. Each country stockpiled arms and supplies for an army that ran into the millions. Germany in 1874 had a regular professional army of 420,000 with an additional 1.3 million reserves. By 1897, the regular army was 545,000 strong and the reserves 3.4 million. The French in 1897 had 3.4 million reservists, Austria 2.6 million, and Russia 4.0 million. The various national war plans had been perfected by 1914 but with Russia and Austria trailing in effectiveness. Recent wars since 1865 had typically been short: a matter of months. All war plans called for a decisive opening and assumed victory would come after a short war. None planned for the food and munitions needs of the long stalemate that actually happened in 1914 to 1918.[120][121]

As David Stevenson put it, "A self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness... was an essential element in the conjuncture that led to disaster.... The armaments race... was a necessary precondition for the outbreak of hostilities." David Herrmann goes further by arguing that the fear that "windows of opportunity for victorious wars" were closing, "the arms race did precipitate the First World War." If Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated in 1904 or even in 1911, Herrmann speculates, there might have been no war. It was "the armaments race and the speculation about imminent or preventive wars" that made his death in 1914 the trigger for war.[122]

One of the aims of the First Hague Conference of 1899, held at the suggestion of Tsar Nicholas II, was to discuss disarmament. The Second Hague Conference was held in 1907. All signatories except for Germany supported disarmament. Germany also did not want to agree to binding arbitration and mediation. The Kaiser was concerned that the United States would propose disarmament measures, which he opposed. All parties tried to revise international law to their own advantage.[123]

[]

Historians have debated the role of the German naval buildup as the principal cause of deteriorating Anglo-German relations. In any case, Germany never came close to catching up with Britain.

Supported by Wilhelm II's enthusiasm for an expanded German navy, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz championed four Fleet Acts from 1898 to 1912. From 1902 to 1910, the Royal Navy embarked on its own massive expansion to keep ahead of the Germans. The competition came to focus on the revolutionary new ships based on the Dreadnought, which was launched in 1906 and gave Britain a battleship that far outclassed any other in Europe.[124][125]

| Naval strength of powers in 1914 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Personnel | Large Naval Vessels (Dreadnoughts) |

Tonnage |

| Russia | 54,000 | 4 | 328,000 |

| France | 68,000 | 10 | 731,000 |

| Britain | 209,000 | 29 | 2,205,000 |

| TOTAL | 331,000 | 43 | 3,264,000 |

| Germany | 79,000 | 17 | 1,019,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 16,000 | 4 | 249,000 |

| TOTAL | 95,000 | 21 | 1,268,000 |

| (Source: [126]) | |||

The overwhelming British response proved to Germany that its efforts were unlikely ever to equal the Royal Navy. In 1900, the British had a 3.7:1 tonnage advantage over Germany; in 1910, the ratio was 2.3:1 and in 1914, it was 2.1:1. Ferguson argues, "So decisive was the British victory in the naval arms race that it is hard to regard it as in any meaningful sense a cause of the First World War."[127] That ignored the fact that the Kaiserliche Marine had narrowed the gap by nearly half and that the Royal Navy had long intended to be stronger than any two potential opponents combined. The US Navy was in a period of growth, which made the German gains very ominous.

In Britain in 1913, there was intense internal debate about new ships because of the growing influence of John Fisher's ideas and increasing financial constraints. In 1914, Germany adopted a policy of building submarines, instead of new dreadnoughts and destroyers, effectively abandoning the race, but it kept the new policy secret to delay other powers from following suit.[128]

Russian interests in Balkans and Ottoman Empire[]

The main Russian goals included strengthening its role as the protector of Eastern Christians in the Balkans, such as in Serbia.[129] Although Russia enjoyed a booming economy, growing population, and large armed forces, its strategic position was threatened by an expanding Ottoman military trained by German experts that was using the latest technology. The start of the war renewed attention of old goals: expelling the Ottomans from Constantinople, extending Russian dominion into eastern Anatolia and Persian Azerbaijan, and annexing Galicia. The conquests would assure the Russian predominance in the Black Sea and access to the Mediterranean.[130]

Technical and military factors[]

Short-war illusion[]

Traditional narratives of the war suggested that when the war began, both sides believed that the war would end quickly. Rhetorically speaking, there was an expectation that the war would be "over by Christmas" in 1914. That is important for the origins of the conflict since it suggests that since it was expected that the war would be short, statesmen tended not to take gravity of military action as seriously as they might have done so otherwise. Modern historians suggest a nuanced approach. There is ample evidence to suggest that statesmen and military leaders thought the war would be lengthy and terrible and have profound political consequences.[citation needed]

While it is true all military leaders planned for a swift victory, many military and civilian[citation needed] leaders recognised that the war might be long and highly destructive. The principal German and French military leaders, including Moltke, Ludendorff, and Joffre, expected a long war.[131] British Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener expected a long war: "three years" or longer, he told an amazed colleague.

Moltke hoped that if a European war broke out, it would be resolved swiftly, but he also conceded that it might drag on for years, wreaking immeasurable ruin. Asquith wrote of the approach of "Armageddon" and French and Russian generals spoke of a "war of extermination" and the "end of civilization." British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey famously stated just hours before Britain declared war, "The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime."

Clark concluded, "In the minds of many statesmen, the hope for a short war and the fear of a long one seemed to have cancelled each other out, holding at bay a fuller appreciation of the risks."[132]

Primacy of offensive and war by timetable[]

Moltke, Joffre, Conrad, and other military commanders held that seizing the initiative was extremely important. That theory encouraged all belligerents to devise war plans to strike first to gain the advantage. The war plans all included complex plans for mobilization of the armed forces, either as a prelude to war or as a deterrent. The continental Great Powers' mobilization plans included arming and transporting millions of men and their equipment, typically by rail and to strict schedules, hence the metaphor "war by timetable."

The mobilization plans limited the scope of diplomacy, as military planners wanted to begin mobilisation as quickly as possible to avoid being caught on the defensive. They also put pressure on policymakers to begin their own mobilization once it was discovered that other nations had begun to mobilize.

In 1969, A. J. P. Taylor wrote that mobilization schedules were so rigid that once they were begun, they could not be canceled without massive disruption of the country and military disorganisation. Thus, diplomatic overtures conducted after the mobilizations had begun were ignored.[133]

Russia ordered a partial mobilization on 25 July against Austria-Hungary only. Their lack of prewar planning for the partial mobilization made the Russians realize by 29 July that it would be impossible and interfere with a general mobilization.

Only a general mobilization could be carried out successfully. The Russians were, therefore, faced with only two options: canceling the mobilization during a crisis or moving to full mobilization, the latter of which they did on 30 July. They, therefore, mobilized along both the Russian border with Austria-Hungary and the border with Germany.