Nikola Pašić

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

His Excellency Nikola Pašić Никола Пашић | |

|---|---|

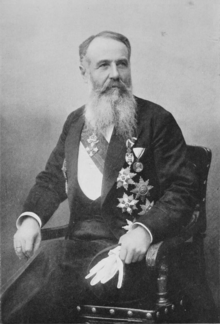

Pašić c. 1914 | |

| 4th Prime Minister of Yugoslavia | |

| In office 6 November 1924 – 8 April 1926 | |

| Monarch | Alexander I |

| Preceded by | Ljubomir Davidović |

| Succeeded by | Nikola Uzunović |

| In office 1 January 1921 – 28 July 1924 | |

| Monarch | Peter I Alexander I |

| Preceded by | Milenko Vesnić |

| Succeeded by | Ljubomir Davidović |

| In office 1 December 1918 – 22 December 1918 Acting | |

| Monarch | Peter I |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Stojan Protić |

| Prime Minister of Serbia | |

| In office 12 September 1912 – 1 December 1918 | |

| Monarch | Peter I |

| Preceded by | Marko Trifković |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| In office 24 October 1909 – 4 July 1911 | |

| Monarch | Peter I |

| Preceded by | Stojan Novaković |

| Succeeded by | Milovan Milovanović |

| In office 29 April 1906 – 20 July 1908 | |

| Monarch | Peter I |

| Preceded by | Sava Grujić |

| Succeeded by | Petar Velimirović |

| In office 10 December 1904 – 28 May 1905 | |

| Monarch | Peter I |

| Preceded by | Sava Grujić |

| Succeeded by | Ljubomir Stojanović |

| In office 23 February 1891 – 22 August 1892 | |

| Monarch | Alexander I |

| Preceded by | Sava Grujić |

| Succeeded by | Jovan Avakumović |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 December 1845 Zaječar, Serbia |

| Died | 10 December 1926 (aged 80) Belgrade, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes |

| Resting place | New Cemetery |

| Political party | People's Radical Party |

| Spouse(s) | Đurđina Duković |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Belgrade Higher School Federal Polytechnic School |

| Signature | |

Nikola Pašić (Serbian Cyrillic: Никола Пашић, pronounced [nǐkola pǎʃitɕ]; 18 December 1845 – 10 December 1926) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and diplomat who was a leading political figure for almost 40 years. He was the leader of the People's Radical Party and, among other posts, was twice a mayor of Belgrade (1890–91 and 1897), several times Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Serbia (1891–92, 1904–05, 1906–08, 1909–11, 1912–18) and Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918, 1921–24, 1924–26).

He was an important politician in the Balkans, who, together with his counterparts, like Eleftherios Venizelos in Greece, managed to strengthen their emergent national states against foreign influence and interference, most notably those of Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire.

Early life[]

Pašić was born in Zaječar, Principality of Serbia. According to Slovenian ethnologist , Pašić's ancestors migrated from the Tetovo region in the 16th century and founded the village of Zvezdan near Zaječar.[1] Pašić himself said that his ancestors settled from the area of the Lešok Monastery in Tetovo.[1] Jovan Dučić concluded that Pašić hailed from Veliki Izvor near Zaječar, and that Pašić's ancestry in Tetovo had been long lost.[2] Bulgarian ethnologist Stilian Chilingirov stated that Pashić's roots were from the village of Veliki Izvor, founded during the 18th century by refugees from the Ottoman Bulgarian village of Golyam Izvor in Teteven area in today Bulgaria.[3] Ljubomir Miletić also claimed that Pašić's grandfather settled in Veliki Izvor from Teteven area, which was refuted by Serbian authors.[1] claiming his parents were both born in Zaječar.[4] However, the village of Veliki Izvor, was really founded by refugees from the village of Golyam Izvor, Teteven area.[5] Carlo Sforza mentioned that Pašić "was lucky in another respect, he belonged to the Shopi community".[6]

Pašić completed elementary school in Zaječar, and finished his gymnasium work in Negotin and Kragujevac.[7][8] In the fall of 1865, he enrolled in the Belgrade Higher School and in 1867 received a state scholarship to study railroad engineering at the Polytechnical School in Zürich.[8] Historian Gale Stokes wrote that Pašić was a "serious student" who "went beyond the required subjects of his specialization".[9] According to Stokes, Pašić's early socialist ideals were shaped by German experiences rather than Marxist or Russian populist, as his studies were focused on German history and contemporary events which were taught by Germanophile professors.[9] He graduated as an engineer but, apart from his brief participation in the construction of the Vienna-Budapest railroad, he never worked in this field.[10]

Radical Party[]

Origins[]

While a student in Zürich, Pašić lived near other Serbian students and became politically involved, initially as an organizer.[11] Some of these students would later become the core of the Socialist and Radical movement in Serbia. One of them was Svetozar Marković, who would become a major socialist ideologue in Serbia.[12] Along with Marković, Pera Velimirović, Jovan Žujović, and others, Pašić became an early member of the "Radical Party".[13]

After returning to Serbia, Pašić went to Bosnia to support the anti-Ottoman uprising of Nevesinjska puška.[14] The Socialists started publishing Samouprava which later became the official bulletin of the Radical Party.[15] After Marković's death in 1875, Pašić became the leader of the movement and in 1878 was elected to the National Assembly of Serbia, even before the party was formed. In 1880, he made an unprecedented move in the Serbian political scene by forming an opposition deputies' club in the assembly. Finally, a party program was completed in January 1881 and the Radical Party, the first systematically organized Serbian party, was officially established, with Pašić elected its first president.[16]

Timok Rebellion[]

The party and Pašić quickly gained popularity; the Radicals received 54 percent of the vote in the September 1883 elections, while the Progressive Party, favored by King Milan Obrenović IV only got 30 percent.[17] Despite the Radicals' clear victory, the pro-Austrian king, who disliked the pro-Russian Pašić and the Radical party, nominated old non-partisan hardliner Nikola Hristić to form a government.[18][19] The assembly refused to cooperate and the session was suspended.[20]

The atmosphere was made worse when Hristić attempted to take away peasants' guns, in order to establish a regular army.[20] As a result, clashes began in eastern Serbia, in the Timok valley. King Milan blamed the unrest on the Radicals and sent troops to crush the rebellion. Pašić was sentenced to death in absentia and he narrowly avoided arrest by fleeing to Hungary.[20] Twenty-one others were sentenced to death and executed,[20] and 734 more were imprisoned.

Exile in Bulgaria[]

For the next six years, Pašić lived with relatives in Bulgaria, supported by the Bulgarian government. He lived in Sofia, where he worked as building contractor, and worked for a short time in the Ministry of Interior According to Bulgarian sources, he spoke quite fluent Bulgarian, but mixed it with a large number of Serbian words and phrases, and it is claimed that he asked Petko Karavelov's friends who hailed from Stara Planina about the characteristics of that region in Bulgaria, explaining that his ancestors had migrated from there to Serbia some generations before.[21]

Bulgarian testimonies completely differ in one important respect, whether Pašić worked actively in politics during his exile in Sofia.[22] The official Bulgarian support became one of several reasons for Milan's decision to start the Serbo-Bulgarian War in 1885.[citation needed] After suffering a decisive defeat, Milan granted an amnesty for those sentenced for the Timok rebellion, but not for Pašić, who remained in Bulgarian exile until Milan's abdication in 1889.[citation needed] A few days later the newly formed Radical cabinet of Sava Grujić pardoned Pašić.[23]

High politics 1890–1903[]

President of assembly and mayor[]

On 13 October 1889, Pašić was elected president of the National Assembly, a duty he would perform (de jure though, not de facto) until 9 January 1892. He was also elected mayor of Belgrade from 11 January 1890 to 26 January 1891. His presiding over the assembly saw the largest number of laws being voted in the history of Serbian parliamentarism, while as the mayor of Belgrade he was responsible for cobbling the muddy city streets. He was reelected twice as president of the National Assembly from 13 June 1893 to April 1895 (though from September 1893 only in name; his deputy Dimitrije Katić acted for him) and 12 July 1897 to 29 June 1898 and once more mayor of Belgrade 22 January 1897 to 25 November 1897.[24]

After wisely not accepting to head the government immediately after his return from exile, Nikola Pašić became prime minister for the first time on 23 February 1891. However, ex-king Milan returned to Serbia in May 1890 and again began campaigning against Pašić and the Radicals. On 16 June 1892, Kosta Protić, one of three regents during the minority of Alexander Obrenović V, died. Under the constitution, the National Assembly was to elect a new regent, but as the assembly was on a several months vacation, Pašić had to call for an emergency session. Jovan Ristić, the most powerful regent, fearing Pašić might be elected co-regent and thus undermine his position, refused to allow the extra session, and Pašić resigned as prime minister on 22 August 1892. During his tenure, he was also foreign minister from 2 April 1892 and acting finance minister from 3 November 1891.[24]

Alexander's coup d'état[]

After King Alexander declared himself of age ahead of time and dismissed the regency, he offered a moderate Radical Lazar Dokić to form a government. Though he received approval from some members of the Radical party to participate in the government, Pašić refused. In order to exclude him from the political scene in Serbia, Alexander sent Pašić as his extraordinary envoy to Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1893–1894. In 1896, the king managed to force Pašić to back off from pushing for constitutional reforms. However, since 1897 both kings, Milan and Alexander, ruled almost jointly; as both disliked Pašić, in 1898 they had him imprisoned for 9 months because Samouprava published a statement about his previous opposition to King Milan. Pašić claimed he was misquoted, with no effect.[25]

Ivandan's assassination attempt[]

Former fireman, Đura Knežević, who was sentenced to death, tried to assassinate ex-king Milan in June 1899 (Serbian: Ивандањски атентат). The same evening, Milan declared that the Radical Party tried to kill him and all heads of the Radical Party were arrested, including Pašić who had just been released from prison from his previous sentence.[26] The accusations that the Radicals or Pašić were linked to the assassination attempt were unfounded. Still, Milan insisted that Nikola Pašić and Kosta Taušanović be sentenced to death.[27] Austria-Hungary feared that the execution of the pro-Russian Pašić would force Russia to intervene, abandoning an 1897 agreement to leave Serbia in status-quo. A special envoy was sent from Vienna to Milan to warn him that Austria would boycott the Obrenović dynasty if Pašić was executed. Noted Serbian historian Slobodan Jovanović later claimed that the entire assassination was staged so that Milan could get rid of the Radical Party.

Imprisoned and unaware of Austria-Hungary's interference,[28] Pašić confessed that the Radical Party had been disloyal to the dynasty, which probably saved many people from prison.[29] As part of the deal reached with the interior minister Đorđe Genčić, the government officially left its own role out of the statement, so that it appeared that Pašić behaved cowardly and succumbed to the pressure. Pašić was sentenced to five years but released immediately. This caused future conflict within the Radical Party as younger members considered Pašić a coward and traitor, and split from the party. For the remainder of Alexander's rule, Pašić retired from politics. Although the young monarch disliked Pašić, he was often summoned for consultations but would refrain from giving advice and insist that he is no longer involved with politics.

Golden age of democracy 1903–1914[]

Royal assassination[]

Nikola Pašić was not among the conspirators who plotted to assassinate King Alexander. The assassination occurred on the night of 10-11 June [O.S. 28-29 May] 1903, and both the King and Queen Draga Mašin were killed, as well as Prime Minister Dimitrije Cincar-Marković and Defence Minister . The Radical Party did not form the first cabinet after the coup d'état, but after winning the elections on 4 October 1903, they remained in almost uninterrupted power for the next 15 years.

In the beginning, the Radicals opposed the appointment of a new king, Peter I Karađorđević, calling his appointment illegal. But Pašić later changed his mind after seeing how people willingly accepted the new monarch as well as king Peter I, educated in Western Europe, was a democratic, mild ruler, unlike the last two despotic and erratic Obrenović sovereigns. As it will be shown in the next two decades, the major clash between the king and the prime minister will be Pašić's refusal to raise to royal appanage.[citation needed]

Nikola Pašić became foreign minister on 8 February 1904 in Sava Grujić's cabinet and headed a government under his own presidency 10 December 1904 to 28 May 1905, continuing as foreign minister as well. During the following decade, under the leadership of Pašić and the Radical Party, Serbia grew so prosperous that many historians call this period the modern golden age of Serbia. The country evolved into a European democracy and with financial and economic growth, political influence also grew which caused constant problems with Serbia's largest neighbour, Austria-Hungary, which even developed plans to turn Serbia into one of its provinces (already in 1879 German chancellor Otto von Bismarck said that Serbia is the stumbling-block in Austria's development).[citation needed]

Austro-Hungarian customs war[]

As Austro-Hungarian latent provocations of Serbia concerning Serbs living in Bosnia and Herzegovina, officially still part of the Ottoman Empire but occupied by Austria-Hungary since 1878 and causing problems to Serbian export which mainly went through Austria (as Serbia is landlocked) didn't bring results, Austria-Hungary began open customs war in 1906. Pašić formed another cabinet from 30 April 1906 to 20 July 1908. Pressured by the Austrian government which asked from Serbia to buy everything from Austrian companies, from salt to cannons, he replied to Austrian government that he personally would do that, but that the assembly is against it and in democratic countries that's what counts.[citation needed]

Austria closed the borders which did cause a severe blow to the Serbian economy initially, but later it will bounce back even more developed than it was, thanks to the Pašić swift change towards the Western European countries. He forced conspirators of the 1903 coup into retirement which was a condition for reestablishing diplomatic connections with the United Kingdom, he bought cannons from France, etc. In the midst of the customs war, Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 which caused mass protests in Serbia and political instability, but Pašić managed to calm the situation down. In this period, Pašić's major ally, Imperial Russia, was not much of a help being defeated by Japan in Russo-Japanese War and under series of revolutions.[citation needed]

Balkan Wars[]

Pašić formed two more cabinets (24 October 1909 to 4 July 1911 and from 12 September 1912). He was one of the major players in the formation of the Balkan League which later resulted in the First Balkan War (1912–13) and the Second Balkan War (1913) which almost doubled the size of Serbia with the territories of what was at the time considered Old Serbia (Kosovo, Metohija and Vardar Macedonia), retaken from the Ottomans after five centuries.[citation needed] He clashed with some military structures about the handling of the newly acquired territories. Pašić believed the area should be included into the Serbian political and administrative system through the democratic elections, while the army sought to keep the areas under the military occupation. After one year of tensions Pašić dismissed the military administrator of Old Serbia and scheduled new elections for 1914 but the outbreak of World War I prevented it.[citation needed]

Outbreak of the Great War[]

After the Assassination in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 when members of the Serbian revolutionary organization Young Bosnia assassinated the Austro-Hungarian heir-apparent Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Austro-Hungarian government immediately accused the Serbian government of being behind the assassination.[citation needed] The general consensus today is that government did not organize it, but how much Pašić knew about it is still a controversial issue and it appears that every historian has his or her own opinion on the subject: Pašić knew nothing (Ćorović); Pašić knew something is about to happen and told Russia that Austria would attack Serbia before the assassination (Dragnić); Pašić knew but as the assassins were connected to the powerful members of the Serbian intelligence, was afraid to do anything about it personally so he warned Vienna (Balfour).[citation needed]

Austria presented him the July Ultimatum, written together with the envoys of the German ambassadors in such a vein that it would be unlikely for the Serbian government. After extensive consultations in the country itself and formidable pressure from outside to accept it, Pašić told the Austrian ambassador (who had already packed his bags) that Serbia accepts all the ultimatum demands except that Austrian police can independently travel throughout Serbia and conduct its own investigation.[citation needed] Austria-Hungary answered by formally declaring war on Serbia on 28 July 1914.

World War I and Yugoslavia[]

Glory, defeat and the South Slav state[]

Serbian defeat was considered to be imminent, at least by external onlookers, compared to the strength of the Austria-Hungary. Serbia had obviously prepared well, however, and after a series of battles in 1914–1915 (Battle of Cer, Battle of Kolubara), the loss and recapture of Belgrade, and a Serbian counter-offensive with occupation of some Austrian territories (in Syrmia and eastern Bosnia), the Austrian army backed off. On 5 July 1914, things changed as old King Peter I relinquished his duties to the heir apparent Alexander, making him his regent.[citation needed]

On 17 September 1914, Pašić and Albanian leader Essad Pasha Toptani signed in Niš the secret Treaty of Serbian-Albanian Alliance.[30] The treaty had 15 points which focused on setting up joint Serbian-Albanian political and military institutions and military alliance of Albania and Kingdom of Serbia. The treaty also envisaged building of the rail-road to Durres, financial and military support of the Kingdom of Serbia to Essad Pasha's position of Albanian ruler and drawing of the demarcation by special Serbo-Albanian commission.[31] In October 1914, Essad Pasha returned to Albania. With Italian and Serbian financial backing, he established armed forces in Dibër and captured the interior of Albania and Dures. Pašić ordered that his followers be aided with money and arms.[32]

Unlike Peter, Alexander was not a democratic spirit, rather a dictatorial one and personally disliked Pašić and talk of democracy. Open strife began very soon, when Serbia was proposed the London Pact by which it was supposed to expand into most of the ethnic Serbian territories to the west, including a section of the Adriatic coast and some ethnic Albanian territories in northern Albania. In return, Serbia was supposed to relinquish part of Vardar Macedonia to Bulgaria so that the latter would enter the war on the Entente side.[citation needed] Both Pašić and regent Alexander were against this as they considered it to be the betrayal of the Croatians, Slovenians and Serbian sacrifices in the Balkan Wars, as negotiations for the future South Slav state already began. However, Pašić and king Peter were not personally much for the Yugoslav idea unlike the regent who pushed the issue for creating as large a state as possible. Serbia refused the pact and was attacked by Austria-Hungary, Germany and Bulgaria. The Government and the army retreated to the south in the direction of Greece, but were cut off by Bulgarian forces and had to go through Albania and to the Greek island of Corfu where the Corfu Declaration was signed in 1917 preparing the ground for the future South Slav state of Yugoslavia.[citation needed]

Creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes[]

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (SHS) was officially proclaimed on 1 December 1918, and, being the Prime Minister of Serbia at that time, Pašić was generally considered the de facto Prime Minister of the new South Slav state, as well.[citation needed] The political agreement was reached that Pašić would continue on as Prime Minister when the first government of the new state was to be formed, but as a result of his longtime dislike of Pašić, regent Alexander nominated Stojan Protić to form the government. Consequently, Pašić stepped down on 20 December 1918.[citation needed]

Despite being removed from the government, as the most experienced of politicians, Nikola Pašić was the main negotiator for the new state at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. In an effort to secure the maximalist[further explanation needed] agenda of the regent, he did not push on the question of the Czech Corridor, Timișoara, and Szeged, managed to secure borders with Albania and Bulgaria, but failed to annex Fiume (which became an independent state) and most of Carinthia (which remained part of Austria). At the time when Benito Mussolini was willing to modify the Treaty of Rapallo, which cut off a quarter of Slovene ethnic territory from the remaining three-quarters of Slovenes living in the Kingdom of SHS, in order to annex the independent state of Rijeka to Italy, Pašić's attempts to correct the borders at Postojna and Idrija were undermined by regent Alexander preferring "good relations" with Italy.[33]

Elections held on 28 November 1920 showed that the Radical Party was the second strongest in the country, having just one seat less than the Yugoslav Democratic Party (91 to 92, respectively, out of 419 seats). However, Pašić managed to form a coalition and became prime minister again on 1 January 1921.[citation needed]

Pašić became a very large landowner in the country due to expropriation of Albanian land in Kosovo and other areas.[34]

Vidovdan Constitution[]

As soon as talks about the constitution of the new state began, two diametrically opposite sides, Serbian and Croatian, were established. Both Pašić and regent Alexander wanted a unitary state but for different reasons. Pašić considered that the Serbs could be outvoted in such a state and that an unconsolidated and heterogeneous entity would fall apart if it was a federal one, while the regent simply didn't like to share power with others, which was shown 8 years later when he conducted a coup d'état.[citation needed]

Stjepan Radić, a leading Croatian politician for a joint Serbian-Croatian state would be a temporary solution on the way to Croatian independence,[citation needed] asked for a federal republic. As Pašić had majority in the assembly, a new constitution was proclaimed on Vidovdan (St. Vitus day), 28 June 1921, organizing the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as a parliamentary (albeit highly unitary) monarchy, abolishing even the remaining shreds of autonomy which had Slovenia, Croatia, Dalmatia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Vojvodina (provincial governments). In the early 1920s, the Yugoslav government of Prime Minister Pašić used police pressure over voters and ethnic minorities, confiscation of opposition pamphlets[35] and other measures of election rigging to keep the opposition, mainly the autonomy-minded Croats, in minority in the Yugoslav parliament.[36][37]

Pašić remained Prime Minister until 8 April 1926, with a short break 27 July 1924 to 6 November 1924, when the government was headed by Ljuba Davidović. After relinquishing temporarily the post to his party colleague Nikola Uzunović, now a king, Alexander refused to reappoint Pašić using as a pretext the scandals of Pašić's son Rade. The following day, on 10 December 1926, Nikola Pašić suffered a heart attack and died in Belgrade, about a week before his 81st birthday. He was interred in Belgrade's New Cemetery. Milenko Vesnić is interred to the right of Pašić's grave and Janko Vukotić is interred to the left of the grave.[38]

Political views[]

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (September 2020) |

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2020) |

Anticommunist[]

Pašić was widely criticized by the Communists as he prevented them from participating in the political life after the 1920 elections and the series of terrorist attacks by the Communists on government officials, and banned the Communist party officially proclaiming it a criminal organization on 21 August 1921. In the early 1920s, he was accused of using police pressure over voters and ethnic minorities, confiscation of opposition pamphlets and other measures of election rigging to keep the opposition, mainly the separatist Stjepan Radić, in minority in Yugoslav parliament.[36][dead link]

After 1945, he was condemned by the new Communist authorities and was labeled a leader of the "great Serbian hegemony", with his accomplishments in building modern Serbia being completely pushed aside.[citation needed]

Proposed Serbian dominance[]

He has been assailed because of the unitary composition of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and his opinion that Serbs, being the plurality, should always have the leading role.[citation needed]

Opposing the joint South Slavic state from the beginning, he was accused of pushing the Greater Serbian agenda, national concept of concentrated power in the hands of Belgrade.[37][dead link] The Croatian Communist theoretician Otokar Keršovani coined a phrase about Pašić: "His name will remain in history more because it is connected to historical events, rather than the historical events being connected to his name".[citation needed]

Private life[]

Nikola Pašić married Đurđina Duković, daughter of a wealthy Serbian grains trader from Trieste. They were married in the Russian church in Florence to avoid the gathering of the numerous Serbian colony in Trieste and had three children: son Radomir-Rade and daughters Dara and Pava. Radomir-Rade had two sons: Vladislav, an architect (died 1978) and (1918–2015), an Oxford University law graduate who resided in Toronto, Canada, where he founded a Serbian National Academy.[39]

Legacy[]

A central square in Belgrade is named after him, Square of Nikola Pašić (Serbian: Трг Николе Пашића/Trg Nikole Pašića). During Communist regime, the square was named after Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The 4.2 meter tall bronze statue of Pašić is erected on the square, overlooking the building of the assembly. He is included in The 100 most prominent Serbs. Pašić was awarded the Russian Order of the White Eagle with brilliants, the Order of Carol I of Romania and Order of Karađorđe's Star.[40]

Media portrayals[]

- In 1995 TV miniseries The End of Obrenović Dynasty, Nikola Pašić was portrayed by actor Petar Kralj.[41]

- The Last Audience, a television miniseries based on the biography of Nikola Pašić and directed by George Kadijevich, was produced in 2008 by the Serbian broadcasting service RTS.[42]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zbornik Matice srpske za književnost i jezik. Matica srpska. 1974. p. 359.

Милетић је претпостављао да је Никола Пашић пореклом из Тетевена, одакле му је дошао отац или дед. Ја ��ам га упозорио да словеначки етнолог Нико Жупанич констатује да је Н. Пашић пореклом из трговачке породице која се под крај XVI века доселила од Тетова и основала село Звездан код Зајечара (Станојевићева Енциклопедија III, 309) а и сам Пашић у више ма- хова казивао је да су му се стари доселили из околине тетовскога манастира Леш[о]ка. Ово је између осталога казао мом оцу Петру, с којим је зајед- но суђен због ивањданскога атентата, а говорио је тако у Бури Илкићу, школ- ском другу свога сина и домаћем пријатељу породице, који је још жив, као и другима кад би се распитивали

- ^ Jovan Dučić (1969). Sabrana djela. 6. p. 197.

Пашић је пореклом из Извора у близини За- јечара. Тамо се налази неко људско насеље где су сви људи мање него осредњи, плавих јасних очију, који мало говоре, а воле брзе коње. Пашић је сам за своју породицу говорио да је из Тето- ва у Маћедонији, макар што се онамо затро сва- ки спомен на његове претке; а Бугари су то об- ртали говорећи да је Пашић из Тетувена у Бу- гарској

- ^ Чилингиров, Стилиян. Какво е дал българинът на другите народи. 1938, 1939, 1941, 1991, 2006. с. 90-91.

- ^ Dimitrijević 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Представители от тетевенското село Голям извор гостуваха на с. Велики извор, община Зайчар, Сърбия. 27 Сеп 2018 г. Официален сайт на Община Тетевен.

- ^ Sforca 1990, p. 16, " Пашић је имао још једну срећу: припадао је шопској...".

- ^ Dragnich 1974, p. 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stokes 1990, p. 56.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stokes 1990, p. 58.

- ^ Stokes 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Stokes 1990, p. 57.

- ^ Stokes 1990, p. 330.

- ^ Stokes 1990, p. 43.

- ^ Ćorović, Vladimir (1997). Istorija srpskog naroda, Book 1.

- ^ East European Accessions List. Unied States Library of Congress. 1956. p. 62.

- ^ Djokic 2010, p. 128.

- ^ "DA LI JE NIKOLA PAŠIĆ ZASLUŽIO OVAKAV KRAJ? Srbi su ga OBOŽAVALI, a porodica mu je UNIŠTILA KARIJERU". Telegraf.rs. 10 December 2015.

- ^ Dragnich 1974, p. 26.

- ^ MacKenzie, David (1996). Violent Solutions: Revolutions, Nationalism, and Secret Societies in Europe to 1918. University Press of America. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-76180-399-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McClellan, Woodford (2015). Svetozar Markovic and the Origins of Balkan Socialism. Princeton University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-40087-585-6.

- ^ Sforca 1990, p. 36, "Пашић је говорио доста течно бугарски, али је у говор мешао велики број српских речи и израза. Оне младе пријатеље Каравелове који су били пореклом из области Старе Планине Пашић је често питао о карактеристика- ма тога краја Бугарске. Објашњавао им је да су се његови преци иселили одатле у Србију пре неколико генерација. Бугарска сведочанства потпуно се разилазе у једном важном питању: да ли се Пашић бавио активном политиком за време свога изгнанства у Софији.".

- ^ Sforca 1990, p. 36.

- ^ St. Protić, Milan (2015). Between Democracy and Populism: Political Ideas of the Peopleʹs Radical Party in Serbia:(The Formative Period: 1860ʹs to 1903). Balkanološki institut SANU. p. 53. ISBN 978-8-67179-094-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dragnich (1998) pp 36-37.

- ^ Djokic 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Draganich, Alex N. (1978). The Development of Parliamentary Government in Serbia. East European quarterly. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-91471-037-0.

- ^ Draganich, Alex N. (1998). Serbia and Yugoslavia: Historical Studies and Contemporary Commentaries. East European Monographs. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-88033-412-9.

- ^ Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. Harper Collins. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-06219-922-5.

- ^ Pavkovic, Aleksandar; Redan, Peter (2018). The Serbs and their Leaders in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-42977-259-7.

- ^ Bataković, Dušan T. "Serbian government and Essad Pasha Toptani". The Kosovo Chronicles. Belgrade, Serbia: Knižara Plato. ISBN 86-447-0006-5. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

Essad Pasha signed a secret alliance treaty with Pasic on September 17.

- ^ Bataković, Dušan T. "Serbian government and Essad Pasha Toptani". The Kosovo Chronicles. Belgrade, Serbia: Knižara Plato. ISBN 86-447-0006-5. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

The 15 points envisaged the setting up of joint political and military institutions,... focused on a military alliance, the construction of an Adriatic railroad to Durazzo and guarantees that Serbia would support Essad Pasha's election as the Albanian ruler. ...The demarcation between the two countries was to be drawn by a special Serbo-Albanian commission

- ^ Serbian government and Essad Pasha Toptani, balkania.tripod.com; accessed 24 September 2016.

- ^ Čermelj, L. (1955). Kako je prišlo do prijateljskega pakta med Italijo in kraljevino SHS (How the Friendship Treaty between Italy and the Kingdom of SHS Came About in 1924), Zgodovinski časopis, 1-4, p. 195, Ljubljana.

- ^ Qirezi, Arben (2017). "Settling the self-determination dispute in Kosovo". In Mehmeti, Leandrit I.; Radeljić, Branislav (eds.). Kosovo and Serbia: Contested Options and Shared Consequences. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780822981572.

- ^ Balkan Politics, TIME Magazine, 31 March 1923.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Elections, TIME Magazine, 23 February 1925.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Opposition, TIME Magazine, 6 April 1925.

- ^ Beogradska groblja profile

- ^ Politika (11 January 2015). "Umro Nikola Pašić, unuk-imenjak srpskog državnika" (in Serbian). Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. pp. 148, 153.

- ^ The End of Obrenović Dynasty on IMDB

- ^ "The Last Audience". rts.rs. 19 July 2008.

Further reading[]

- DiNardo, Richard L. (2015). Invasion: The Conquest of Serbia, 1915. Santa Barbara: Praeger. ISBN 9781440800924.

- Djokic, Dejan (2010). Pasic & Trumbic: The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-90782-221-6.

- Dragnich, Alex N. (1974). Serbia, Nikola Pašić and Yugoslavia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-81350-773-6.

- Dragnich, Alex N. "Nikola Pasic" in Peter Radan, ed., The Serbs and Their Leaders in the Twentieth Century (1997): 30–57.

- Stokes, Gale (1990). Politics as Development: The Emergence of Political Parties in Nineteenth-century Serbia. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-82231-016-7.

Other languages[]

- Krestić, Vasilije (1 January 1997). Никола Пашић: живот и дело. Завод за уджбенике и наставна средства. ISBN 978-86-17-05390-9.

- Karlo Sforca; Slavenko Terzić; Miloš L. Zečević (1990). Nikola Pašić i ujedinjenje Jugoslovena. Delta Design. ISBN 9788690109517.

- Момчило Вуковић-Бирчанин (1978). Никола Пашић: 1845–1926. M. Vuković-Birčanin.

- Ђорђе Ђ. Станковић (1985). Никола Пашић и југословенско питање. Београдски издавачко-графички завод.

- Milan Gavrilović (1962). Nikola Pašić. Avala.

- Carlo Sforza (1938). Pachitch et l'union des Yougoslaves. Gallimard.

- Alex N. Dragnich (1974). Serbia, Nikola Pašić, and Yugoslavia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-0773-6.

- Milovan Vitezović (2002). Nikola Pašić u anegdotama. Službeni glasnik. ISBN 978-86-7549-271-9.

- Dušan T. Bataković (2006). Nikola Pašić, les radicaux et la "main noire": les défis à la démocratie parlementaire serbe 1903–1917. Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Vasa Kazimirović (1990). Nikola Pašić i njegovo doba: 1845–1926. Nova Evropa.

- Dimitrijević, Miodrag (2004). Nikola Pašić u hodu istorije. Kreativna radionica. ISBN 978-86-83773-20-6.

- Stanojević, Stanoje (1928). "Narodna enciklopedija srpsko-hrvatsko-slovenačka". 3: 352–355.

Pašić Nikola

Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nikola Pašić. |

- "Pašić u anegdotama". Srpsko nasleđe – Istorijske sveske br. 3. NIP GLAS. March 1998.

- Newspaper clippings about Nikola Pašić in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1845 births

- 1926 deaths

- People from Zaječar

- People from the Principality of Serbia

- People's Radical Party politicians

- Prime Ministers of Serbia

- Finance ministers of Serbia

- Prime Ministers of Yugoslavia

- Members of the National Assembly of Serbia

- Mayors of Belgrade

- Yugoslav anti-communists

- Belgrade Higher School alumni

- Serbian expatriates in Bulgaria

- Burials at Belgrade New Cemetery

- Foreign ministers of Serbia

- Construction ministers of Serbia

- Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)