History of the Balkans

The Balkans and parts of this area are alternatively situated in Southeast, Southern, Eastern Europe and Central Europe. The distinct identity and fragmentation of the Balkans owes much to its common and often turbulent history regarding centuries of Ottoman conquest and to its very mountainous geography.[1][2]

Prehistory[]

Mesolithic[]

First human settlement in Europe is Iron Gates Mesolithic (11000 to 6000 BC), located in Danube River, in modern Serbia and Romania. It has been described as "the first city in Europe",[3][4] due to its permanency, organisation, as well as the sophistication of its architecture and construction techniques.

Neolithic[]

Archaeologists have identified several early culture-complexes, including the Cucuteni culture (4500 to 3500 BC), Starcevo culture (6500 to 4000 BC), Vinča culture (5000 to 3000 BC), Linear pottery culture (5500 to 4500 BC), and Ezero culture (3300—2700 BC). The Eneolithic Varna culture in Bulgaria (4600–4200 BC radiocarbon dating) produced the world's earliest known gold treasure and had sophisticated beliefs about afterlife. A notable set of artifacts are the Tărtăria tablets found in Romania, which appear to be inscribed with proto-writing. The Butmir Culture (2600 to 2400 BC), found on the outskirts of present-day Sarajevo, developed unique ceramics, and was likely overrun by the proto-Illyrians[citation needed] in the Bronze Age.

The "Kurgan hypothesis" of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origins assumes gradual expansion of the "Kurgan culture", around 5000 BC, until it encompassed the entire pontic steppe. Kurgan IV was identified with the Yamna culture of around 3000 BC.

Copper Age[]

At ca. 1000 BC,[5] Illyrian tribes appear in what is modern day Albania and all the way aside Adriatic Sea in modern day Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, parts of Serbia, etc. The Thracians[6] lived in Thrace and adjacent lands (now mainly Bulgaria, but also Romania, northeastern Greece, European Turkey, eastern Serbia and North Macedonia), and the closely related Dacians lived in what is today Romania. These three major tribal groups spoke Paleo-Balkan languages, Indo-European languages. The Phrygians seem to have settled in the southern Balkans at first, centuries later continuing their migration to settle in Asia Minor, now extinct as a separate group and language.

Antiquity[]

Iron Age[]

After the period that followed the arrival of the Dorians, known as the Greek Dark Ages or the Geometric Period, the classical Greek culture developed in the southern Balkan peninsula, the Aegean islands and the western Asia Minor Greek colonies starting around the 9th or 8th century BC and peaking with the democracy that developed in 6th and 5th century BC Athens. Later, Hellenistic culture spread throughout the empire created by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE. The Greeks were the first to establish a system of trade routes in the Balkans, and in order to facilitate trade with the natives, between 700 BC and 300 BC they founded a number of colonies on the Black Sea (Pontus Euxinus) coast, Asia Minor, Dalmatia, Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) etc.

By the end of the 4th century BC Greek language and culture were dominant not only in the Balkans but also around the whole Eastern Mediterranean. In the late 6th century BC, the Persians invaded the Balkans, and then proceed to the fertile areas of Europe. Parts of the Balkans and more northern areas were ruled by the Achaemenid Persians for some time, including Thrace, Paeonia, Macedon, and most Black Sea coastal regions of Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia.[7][8] However, the outcome of the Greco-Persian Wars resulted in the Achaemenids being forced to withdraw from most of their European territories.

The Thracian Odrysian empire - the Odrysian kingdom, was the most important Daco-Thracian state union, and probably was founded in the 470s BC, after the Persian defeat in Greece,[9] had its capital at Seuthopolis, near Kazanlak, Stara Zagora Province, in central Bulgaria. Other tribal unions existed in Dacia at least as early as the beginning of the 2nd century BC under King Oroles. The Illyrian tribes were situated in the area corresponding to today's Adriatic coast. The name Illyrii was originally used to refer to a people occupying an area centered on Lake Skadar, situated between Albania and Montenegro (Illyrians proper). However, the term was subsequently used by the Greeks and Romans as a generic name for the different peoples within a well defined but much greater area.[10] In the same way, the territory to the north of the kingdom of Macedon was occupied by the Paeonians, who were also ruled by kings.

Achaemenid Persian Empire (6th to 5th century BC)[]

Around 513 BC, as part of the military incursions ordered by Darius I, a huge Achaemenid army invaded the Balkans and tried to defeat the Western Scythians roaming to the north of the Danube river.[11] Several Thracian peoples, and nearly all of the other European regions bordering the Black Sea (including parts of the modern-day Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia), were conquered by the Achaemenid army before it returned to Asia Minor.[7][11] Darius's highly regarded commander Megabazus was responsible to fulfill the conquers in the Balkans.[11] The Achaemenid troops conquered Thrace, the coastal Greek cities, and the Paeonians.[11][12][13] Eventually, in about 512–511 BC, the Macedonian king Amyntas I accepted the Achaemenid domination and surrendered his country as a vassal state to the Achaemenid Persia.[11] The multi-ethnic Achaemenid army possessed many soldiers from the Balkans. Moreover, many of the Macedonian and Persian elite intermarried. For instance, Megabazus' own son, Bubares, married Amyntas' daughter, Gygaea; and that supposedly ensured good relations between the Macedonian and Achaemenid rulers.[11]

Following the Ionian Revolt the Persian authority in the Balkans was restored by Mardonius in 492,[11] which not only included the re-subjugation of Thrace, but also the full subordinate inclusion of Macedon into the Persian Empire.[14] The Persian invasion led indirectly to Macedonia's rise in power and Persia had some common interests in the Balkans; with Persian aid, the Macedonians stood to gain much at the expense of some Balkan tribes such as the Paeonians and Greeks. All in all, the Macedonians were "willing and useful Persian allies."[15] Macedonian soldiers fought against Athens and Sparta in Xerxes' army.[11]

Although Persian rule in the Balkans was overthrown following the failure of Xerxes' invasion, the Macedonians and Thracians borrowed heavily from the Achaemenid Persians their tradition in culture and economy in the 5th- to mid-4th centuries.[11] Some artificats, excavated at Sindos and Vergina maybe be considered as influenced by Asian practices, or even imported from Persia in the late sixth and early fifth centuries.[11]

Pre-Roman states (4th to 1st centuries BC)[]

Bardylis, a Dardanian chieftain, created a kingdom which turned Illyria into a formidable local power in the 4th century BC. The main cities of this kingdom were Scodra (present-day Shkodra, Albania) and Rhizon (present-day Risan, Montenegro). In 359 BC, King Perdiccas III of Macedon was killed by attacking Illyrians.

But in 358 BC, Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, defeated the Illyrians and assumed control of their territory as far as Lake Ohrid (present-day North Macedonia). Alexander himself routed the forces of the Illyrian chieftain Cleitus in 335 BC, and Illyrian tribal leaders and soldiers accompanied Alexander on his conquest of Persia. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, the Greek states started fighting among themselves again, while up north independent Illyrian polities arose again. In 312 BC, King Glaukias seized Epidamnus. By the end of the 3rd century BC, an Illyrian kingdom based in Scodra controlled parts of northern Albania, and littoral Montenegro. Under Queen Teuta, Illyrians attacked Roman merchant vessels plying the Adriatic Sea and gave Rome an excuse to invade the Balkans.

In the Illyrian Wars of 229 BC and 219 BC, Rome overran the Illyrian settlements in the Neretva river valley and suppressed the piracy that had made the Adriatic unsafe. In 180 BC, the Dalmatians declared themselves independent of the Illyrian king Gentius, who kept his capital at Scodra. The Romans defeated Gentius, the last king of Illyria, at Scodra in 168 BC[citation needed] and captured him, bringing him to Rome in 165 BC. Four client-republics were set up, which were in fact ruled by Rome. Later, the region was directly governed by Rome and organized as a province, with Scodra as its capital. Also, in 168 BC, by taking advantage of the constant Greek civil wars, the Romans defeated Perseus, the last King of Macedonia and with their allies in southern Greece, they became overlords of the region. The territories were split to Macedonia, Achaia and Epirus.

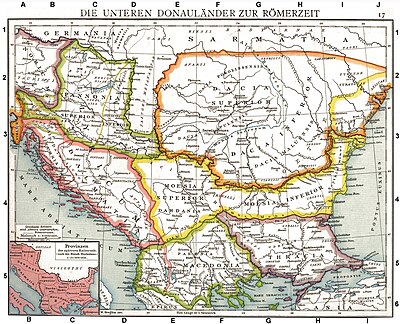

Roman period[]

Starting in the 2nd century BC the rising Roman Republic began annexing the Balkan area, transforming it into one of the Empire's most prosperous and stable regions. To this day, the Roman legacy is clearly visible in the numerous monuments and artifacts scattered throughout the Balkans, and most importantly in the Latin-based languages used by almost 25 million people in the area (the Balkan Romance languages). However, the Roman influence failed to dissolve Greek culture, which maintained a predominant status in the Eastern half of the Empire, and continued to be strong in the southern half of the Balkans.

Beginning in the 3rd century AD, Rome's frontiers in the Balkans were weakened because of internal political and economic disorders. During this time, the Balkans, especially Illyricum, grew to greater importance. It became one of the Empire's four prefectures, and many warriors, administrators and emperors arose from the region. Many rulers built their residences in the region.[16]

Though the situation had stabilized temporarily by the time of Constantine, waves of non-Roman peoples, most prominently the Thervings, Greuthungs and Huns, began to cross into the territory, first (in the case of the Thervingi) as refugees with imperial permission to take shelter from their foes the Huns, then later as invaders. Turning on their hosts after decades of servitude and simmering hostility, Thervingi under Fritigern and later Visigoths under Alaric I eventually conquered and laid waste[citation needed] the entire Balkan region before moving westward to invade Italy itself.

By the end of the Empire the region had become a conduit for invaders to move westward, as well as the scene of treaties and complex political maneuvers by Romans, Goths and Huns, all seeking the best advantage for their peoples amid the shifting and disorderly final decades of Roman imperial power.

Rise of Christianity[]

Christianity first came to the area when Saint Paul and some of his followers traveled in the Balkans passing through Thracian, Illyrian and Greek populated areas. He spread Christianity to the Greeks at Beroia, Thessaloniki, Athens, Corinth and Dyrrachium.[citation needed] Saint Andrew also worked among the Thracians, Dacians and Scythians, and had preached in Dobruja and Pontus Euxinus. In 46 AD, this territory was conquered by the Romans and annexed to Moesia.

In 106 AD the emperor Trajan invaded Dacia. Subsequently, Christian colonists, soldiers and slaves came to Dacia and spread Christianity.

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Emperor Galerius,[17][18][19] was issued in 311 in Serdica (today Sofia, Bulgaria) by the Roman emperor Galerius, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution of Christianity in the East.[20] In the 3rd century the number of Christians grew. When Emperor Constantine of Rome issued the Edict of Milan in 313, thus ending all Roman-sponsored persecution of Christianity, the area became a haven for Christians. Just twelve years later in 325, Constantine assembled the First Council of Nicaea. In 391, Theodosius I made Christianity the official religion of Rome.

The East-West Schism, known also as the Great Schism (though this latter term sometimes refers to the later Western Schism), was the event that divided Christianity into Western Catholicism and Greek Eastern Orthodoxy, following the dividing line of the Empire in Western Latin-speaking and Eastern Greek-speaking parts. Though normally dated to 1054, when Pope Leo IX and Patriarch of Constantinople Michael I Cerularius excommunicated each other, the East-West Schism was actually the result of an extended period of estrangement between the two Churches.

The primary claimed causes of the Schism were disputes over papal authority—the Pope claimed he held authority over the four Eastern patriarchs, while the patriarchs claimed that the Pope was merely a first among equals—and over the insertion of the filioque clause into the Nicene Creed. Most serious (and real) cause of course, was the competition for power between the old and the new capitals of the Roman Empire (Rome and Constantinople). There were other, less significant catalysts for the Schism, including variance over liturgical practices and conflicting claims of jurisdiction.

Early Middle Ages[]

Eastern Roman Empire[]

The Byzantine Empire was the Greek-speaking, Eastern Roman Empire during the Middle Ages, centered at its capital in Constantinople. During most of its history it controlled provinces in the Balkans and Asia Minor. The Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian for a time retook and restored much of the territory once held by the unified Roman Empire, from Spain and Italy, to Anatolia. Unlike the Western Roman Empire, which met a famous if rather ill-defined death in the year 476 AD, the Eastern Roman Empire came to a much less famous but far more definitive conclusion at the hands of Mehmet II and the Ottoman Empire in the year 1453. Its expert military and diplomatic power ensured inadvertently that Western Europe remained safe from many of the more devastating invasions from eastern peoples, at a time when the still new and fragile Western Christian kingdoms might have had difficulty containing it.

The magnitude of influence and contribution the Byzantine Empire made to Europe and Christendom has only begun to be recognised recently. The Emperor Justinian I's formation of a new code of law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, served as a basis of subsequent development of legal codes. Byzantium played an important role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy. Its rich historiographical tradition preserved ancient knowledge upon which splendid art, architecture, literature and technological achievements were built. This is embodied in the Byzantine version of Christianity, which spread Orthodoxy and eventually led to the creation of the so-called "Byzantine commonwealth" (a term coined by 20th-century historians) throughout Eastern Europe. Early Byzantine missionary work spread Orthodox Christianity to various Slavic peoples, amongst whom it still is a predominant religion. Jewish communities were also spread through the Balkans at this time, while the Jews were primarily Romaniotes.[21][22] In a sense of a Greek-influenced "Byzantine commonwealth", the Greek Christian culture and also the Romaniote culture have influenced the emerging cultures both the Christian and the Jewish cultures of the Balkans and of Eastern Europe.[23]

Throughout its history, its borders were ever fluctuating, often involved in multi-sided conflicts with not only the Arabs, Persians and Turks of the east, but also with its Christian neighbours- the Bulgarians, Serbs, Normans and the Crusaders, which all at one time or another conquered large amounts of its territory. By the end, the empire consisted of nothing but Constantinople and small holdings in mainland Greece, with all other territories in both the Balkans and Asia Minor gone. The conclusion was reached in 1453, when the city was successfully besieged by Mehmet II, bringing the Second Rome to an end.

Barbarian incursions[]

Coinciding with the decline of the Roman Empire, many "barbarian" tribes passed through the Balkans, most of whom did not leave any lasting state. During these "Dark Ages", Eastern Europe, like Western Europe, regressed culturally and economically, although enclaves of prosperity and culture persisted along the coastal towns of the Adriatic and the major Greek cities in the south.[24] As the Byzantine Empire withdrew its borders more and more, in an attempt to consolidate its waning power, vast areas were de-urbanised, roads abandoned and native populations may have withdrawn to isolated areas such as mountains and forests.[24]

The first such barbarian tribe to enter the Balkans were the Goths. From northern East Germany, via Scythia, they pushed southwards into the Roman Balkans following the threat of the Huns. These Goths were eventually granted lands inside the Byzantine realm (south of the Danube), as foederati (allies). However, after a period of famine, the proto-Visigoths rebelled and defeated the emperor in 378. The Visigoths subsequently sacked Rome in 410, and in an attempt to deal with them, they were granted lands in France. The Huns, a confederation of a Turkic-Uralic ruling core that subsequently incorporated various Germanic, Sarmatian and Slavic tribes, moved west into Europe entering Pannonia in 400–410 AD. The Huns are supposed to have triggered the great German migrations into western Europe. From their base, the Huns subdued many people and carved out a sphere of terror extending from Germany and the Baltic to the Black Sea. With the death of Attila the Hun in 454 AD, succession struggles led to the rapid collapse of Hun prestige and subsequent disappearance from Europe. In the meantime, the Ostrogoths freed themselves from Hunnish domination in 454 AD and became foedorati as well. The Ostrogoths too migrated westwards, commissioned by the Byzantines, and established a state in Italy. In the second half of the 5th- and first of the 6th century, new Germanic barbarian tribes entered the Balkans. The Gepids, having lived in Dacia in the 3rd century with the Goths, settled Pannonia and eventually conquered Singidunum (Belgrade) and Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica), establishing a short-lived kingdom in the 6th century. The Lombards entered Pannonia in 550s, defeated the Gepids and absorbed them. In 569 they moved into northern Italy, establishing their own kingdom at the expense of the Ostrogoths.

The Slavs, known as the Sklavenoi, migrated in successive waves. Small numbers might have moved down as early as the 3rd century[citation needed] however the bulk of migration did not occur until the 6th century. The Slavs migrated from Central Europe and Eastern Europe and eventually became known as South Slavs. Most still remained subjects of the Roman Empire.

The Avars were a Turkic group (or possibly Mongol[25]), possibly with a ruling core derived from the Rouran that escaped the Göktürks. They entered Central Europe in the 7th century AD, forcing the Lombards to flee to Italy. They continuously raided the Balkans, contributing to the general decline of the area that had begun centuries earlier. After their unsuccessful siege on Constantinople in 626, they limited themselves to Central Europe. They ruled over the Western Slavs that had already inhabited the region. By the 10th century, the Avar confederacy collapsed due to internal conflicts, Frankish and Slavic attacks. The remnant Avars were subsequently absorbed by the Slavs and Magyars.

The Bulgars, Turkic people of Central Asia, first appeared in a wave commenced with the arrival of Asparuh's Bulgars. Asparuh was one of Kubrat's, the Great Khan, successors. They had occupied the fertile plains of the Ukraine for several centuries until the Khazars swept their confederation in the 660s and triggered their further migration. One part of them — under the leadership of Asparuh — headed southwest and settled in the 670s in present-day Bessarabia. In 680 AD they invaded Moesia and Dobrudja and formed a confederation with the local Slavic tribes who had migrated there a century earlier. After suffering a defeat at the hands of Bulgars and Slavs, the Byzantine Empire recognised the sovereignty of Asparuh's Khanate in a subsequent treaty signed in 681 AD. The same year is usually regarded as the year of the establishment of Bulgaria (see History of Bulgaria). A smaller group of Bulgars under Khan Kouber settled almost simultaneously in the Pelagonian plain in western Macedonia after spending some time in Panonia. Some Bulgars actually entered Europe earlier with the Huns. After the disintegration of the Hunnic Empire the Bulgars dispersed mostly to eastern Europe.

The Magyars, led by Árpád, were the leading clan in a ten tribe confederacy. They entered Europe in the 10th century AD, settling in Pannonia. There they encountered a predominantly Slavic populace and Avar remnants. The Magyars were a Uralic people, originating from west of the Ural Mountains. They learned the art of horseback warfare from Turkic people. They then migrated further west around 400AD, settling in the Don-Dnieper area. Here they were subjects of the Khazar Khaganate. They were neighboured by the Bulgars and Alans. They sided with 3 rebel Khazar tribes against the ruling factions. Their loss in this civil war, and ongoing battles with the Pechenegs, was probably the catalyst for them to move further west into Europe.

The local Romans and Romanized remnants of the Iron Age populace of the Balkans began their assimilation into mainly the Slavs and Greeks, however, notable Latin-speaking communities are known to have survived. In literature, these Romance-speakers are known as "Vlachs". In Dacia, Roman colonists and Romanized Dacians retreated in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania after the Roman withdrawal. Archaeological evidence indicate a Romanized population in Transylvania by at least the 8th century. By the 7th and 8th centuries, the Roman Empire existed only south of the Danube River in the form of the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople. In this ethnically diverse closing area of the Roman Empire, Vlachs were recognized as those who spoke Latin, the official language of the Byzantine Empire used only in official documents, until the 6th century when it was changed to the more popular Greek. These original Vlachs probably consisted of a variety of ethnic groups (most notably Thracians, Dacians, Illyrians) who shared the commonality of having been assimilated in language and culture of the Roman Empire with the Roman colonists settled in their areas. Anna Comnene relates in Alexiade about Dacians (instead of Vlachs) from Balkans and from the North side of Danube and they were identified as Romanians.[26] Romance-speaking populations survived on the Adriatic, and the Albanians are believed by some to be descending from partially Romanized Illyrians.

First Bulgarian Empire[]

In the 7th century the Bulgaria was established by Khan Asparuh. It greatly increased in strength in the coming centuries stretching from Dnieper to Budapest and the Mediterranean. Bulgaria dominated the Balkans for the next four centuries and was instrumental in the adoption of Christianity in the region and among other Slavs. Bulgarian Tsar Simeon I the Great, following the cultural and political course of his father Boris I, ordered the creation of the Bulgarian Alphabet, which was later spread by missionaries to the north reaching modern Russia.

High Middle Ages[]

Republic of Venice[]

The Uprising of Asen and Peter was a revolt of Bulgarians and Vlachs[31][32] living in Moesia and the Balkan Mountains, then the theme of Paristrion of the Byzantine Empire, caused by a tax increase. It began on 26 October 1185, the feast day of St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki, and ended with the restoration of Bulgaria with the creation of the Second Bulgarian Empire, ruled by the Asen dynasty.

In building its maritime commercial empire, the Republic of Venice dominated the trade in salt,[33] acquired control of most of the islands in the Aegean, including Cyprus and Crete, and became a major "power" in the Near East and in all the Balkans. Venice seized a number of locations on the eastern shores of the Adriatic sea before 1200, partly for purely commercial reasons, but also because pirates based there were a menace to its trade. The Doge since that time bore the titles of Duke of Dalmatia and Duke of Istria. Venice became a fully imperial power following the Venetian-financed Fourth Crusade, which in 1203 captured and in 1204 sacked and conquered Constantinople, dividing the Byzantine Empire into several smaller states and established the Latin Empire. Venice subsequently carved out a sphere of influence in the Aegean known as the Duchy of the Archipelago, and also gained control of the island of Crete. Weakened by constant warfare with Bulgaria and the unconquered sections of the empire, the Latin Empire eventually fell when Byzantines recaptured Constantinople under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261. The last Latin emperor, Baldwin II, went into exile, but the imperial title survived, with several pretenders to it, until the 14th century.

Late Middle Ages[]

Serbian Empire[]

In 1346, Serbian Empire was established by King Stefan Dušan, known as "Dušan the Mighty", who significantly expanded the state. Under Dušan's rule Serbia was the major power in the Balkans, and a multi-lingual empire that stretched from the Danube to the Gulf of Corinth, with its capital in Skopje. He also promoted the Serbian Archbishopric to the Serbian Patriarchate. Dušan enacted the constitution of the Serbian Empire, known as Dušan's Code, perhaps the most important literary work of medieval Serbia. He was crowned as Emperor and autocrat of the Serbs and Greeks (Romans). His son and successor, Uroš the Weak, lost most of the territory conquered by Dušan, hence his epithet. The Serbian Empire effectively ended with the death of Uroš V in 1371 and the break-up of the Serbian state.

Ottoman invasion[]

In the 14th century Ottoman rule began to extend over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans. Sultan Orhan, captured the city of Bursa in 1326 and made it the new capital of the Ottoman state. The fall of Bursa meant the loss of Byzantine control over Northwestern Anatolia. The important city of Thessaloniki was captured from the Venetians in 1387. The Ottoman victory at Kosovo in 1389 effectively marked the end of Serbian power in the region, paving the way for Ottoman expansion into Europe. The Empire controlled nearly all former Byzantine lands surrounding the city, but the Byzantines were temporarily relieved when Timur invaded Anatolia in the Battle of Ankara in 1402. The son of Murad II, Mehmed the Conqueror, reorganized the state and the military, and demonstrated his martial prowess by capturing Constantinople on 29 May 1453, at the age of 21. The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II cemented the status of the Empire as the preeminent power in southeastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. After taking Constantinople, Mehmed met with the Orthodox patriarch, Gennadios and worked out an arrangement in which the Orthodox Church, in exchange for being able to maintain its autonomy and land, accepted Ottoman authority. The Empire prospered under the rule of a line of committed and effective Sultans. Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) dramatically expanded the Empire's eastern and southern frontiers by defeating Shah Ismail of Safavid Persia, in the Battle of Chaldiran.

Adriatic region[]

From the 14th century, Venice controlled most of the maritime commerce of the Balkans with important colonial possessions on the Adriatic and Aegean coasts. Venice's long decline started in the 15th century, when it first made an unsuccessful attempt to hold Thessalonica against the Ottomans (1423–1430). She also sent ships to help defend Constantinople against the besieging Turks (1453). After the city fell to Sultan Mehmet II, he declared war on Venice. The war lasted thirty years and cost Venice many of the eastern Mediterranean possessions. Slowly the Republic of Venice lost nearly all possessions in the Balkans, maintaining in the 18th century only the Adriatic areas of Istria, Dalmatia and Albania Veneta. The Venetian island of Corfu was the only area of Greece never occupied by the Turks. In 1797 Napoleon conquered Venice and caused the end of the Republic of Venice in the Balkans.

Early modern period[]

Ottoman Empire[]

Much of the Balkans was under Ottoman rule throughout the Early modern period. Ottoman rule was long, lasting from the 14th century up until the early 20th in some territories. The Ottoman Empire was religiously, linguistically and ethnically diverse, and, at times, a much more tolerant place for religious practices when compared to other parts of the world.[34][35] The different groups in the empire were organised along confessional lines, in the so-called the Millet system. Among the Orthodox Christians of the empire (the Rum Millet) a common identity was forged based on a shared sense of time defined by the ecclesiastical calendar, saint's days and feasts.[36]

The social structure of the Balkans in the late 18th century was complex. The Ottoman rulers exercised control chiefly in indirect ways.[37] In Albania and Montenegro, for example, local leaders paid nominal tribute to the Empire and otherwise had little contact. The Republic of Ragusa paid an annual tribute but otherwise was free to pursue its rivalry with the Republic of Venice. The two Romance-speaking principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia had their own nobility, but were ruled by Greek families chosen by the Sultan. In Greece, the elite comprised clergymen and scholars, but there was scarcely any Greek aristocracy. A million or more Turks had settled in the Balkans, typically in smaller urban centers where they were garrison troops, civil servants, and craftsmen and merchants. There were also important communities of Jewish and Greek merchants. The Turks and Jews were not to be found in the countryside, so there was a very sharp social differentiation between the cities and their surrounding region in terms of language, religion and ethnicity. The Ottoman Empire collected taxes at about the 10% rate but there was no forced labor and the workers and peasants were not especially oppressed by the Empire. The Sultan favoured and protected the Orthodox clergy, primarily as a protection against the missionary zeal of Roman Catholics.[38]

Rise of nationalism in the Balkans[]

The rise of Nationalism under the Ottoman Empire caused the breakdown of millet concept. With the rise of national states and their histories, it is very hard to find reliable sources on the Ottoman concept of a nation and the centuries of the relations between House of Osman and the provinces, which turned into states. Unquestionably, understanding the Ottoman conception of nationhood helps us to understand what happened in the Balkans in the late Ottoman period.

- Bulgarian National Revival and National awakening of Bulgaria (18-19th century)

- Serbian Revolution (1804–1815/1817/1833)

- Greek War of Independence (1821–1832)

- Albanian National Awakening (1830-1912)

- Bosnian uprising (1831–1832)

Serbian revolt in Herzegovina in 1875, which led to Serbian-Turkish Wars (1876-1878), and the bloody suppression of the April Uprising in Bulgaria, became occasion of the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and the Liberation of Bulgaria and Serbia in 1878.

Congress of Berlin[]

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a meeting of the leading statesmen of Europe's Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire. In the wake of the Russia's decisive victory in a war with Turkey, 1877–78, the urgent need was to stabilize and reorganize the Balkans, and set up new nations. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who led the Congress, undertook to adjust boundaries to minimize the risks of major war, while recognizing the reduced power of the Ottoman Empire, and balance the distinct interests of the great powers.

As a result, Ottoman holdings in Europe declined sharply; Bulgaria was established as an independent principality inside the Ottoman Empire, but was not allowed to keep all its previous territory. Bulgaria lost Eastern Rumelia, which was restored to the Turks under a special administration. Macedonia, and East and Western Thrace were returned outright to the Turks, who promised reform and Northern Dobrudja became part of Romania, which achieved full independence but had to turn over part of Bessarabia to Russia. Serbia and Montenegro finally gained complete independence, but with smaller territories. Austria took over Bosnia and Herzegovina, and effectively took control of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, in order to separate Serbia and Montenegro. Britain took over Cyprus.[39]

The results were at first hailed as a great achievement in peacemaking and stabilization. However, most of the participants were not fully satisfied, and grievances regarding the results festered until they exploded into World War in 1914. Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece made gains, but far less than they thought they deserved. The Ottoman Empire, called at the time the "sick man of Europe," was humiliated and significantly weakened, rendering it more liable to domestic unrest and more vulnerable to attack. Although Russia had been victorious in the war that caused the conference, it was humiliated at Berlin, and resented its treatment. Austria-Hungary gained a great deal of territory, which angered the South Slavs, and led to decades of tensions in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bismarck became the target of hatred of Russian nationalists and Pan-Slavists, and found that he had tied Germany too closely to Austria in the Balkans.[40]

In the long-run, tensions between Russia and Austria-Hungary intensified, as did the nationality question in the Balkans. The congress was aimed at the revision of the Treaty of San Stefano and at keeping Constantinople in Ottoman hands. It effectively disavowed Russia's victory over the decaying Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War. The Congress of Berlin returned to the Ottoman Empire territories that the previous treaty had given to the Principality of Bulgaria, most notably Macedonia, thus setting up a strong revanchist demand in Bulgaria that in 1912 was one of many causes of the First Balkan War.

20th century[]

Balkan Wars[]

The Balkan Wars were two wars that took place in the Balkans in 1912 and 1913. Four Balkan states defeated the Ottoman Empire in the first war; one of the four, Bulgaria, was defeated in the second war. The Ottoman Empire lost nearly all of its holdings in Europe. Austria-Hungary, although not a combatant, was weakened as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples.[41] The war set the stage for the Balkan crisis of 1914 and thus was a "prelude to the First World War."[42]

World War I[]

Coming of war 1914[]

The monumentally colossal World War I was ignited from a spark in the Balkans, when a Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austrian throne, Franz Ferdinand. Princip was a member of a Serbian militant group called the Crna Ruka (Serbian for "Black Hand").[43] Following the assassination, Austria-Hungary sent Serbia an ultimatum in July 1914 with several provisions largely designed to prevent Serbian compliance. When Serbia only partially fulfilled the terms of the ultimatum, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914.

Many members of the Austro-Hungarian government, such as Conrad von Hötzendorf had hoped to provoke a war with Serbia for several years. They had a couple of motives. In part they feared the power of Serbia and its ability to sow dissent and disruption in the empire's "south-Slav" provinces under the banner of a "greater Slav state". Another hope was that they could annex Serbian territories in order to change the ethnic composition of the empire. With more Slavs in the Empire, some in the German-dominated half of the government hoped to balance the power of the Magyar-dominated Hungarian government. Until 1914 more peaceful elements had been able to argue against these military strategies, either through strategic considerations or political ones. However, Franz Ferdinand, a leading advocate of a peaceful solution, had been removed from the scene, and more hawkish elements were able to prevail. Another factor in this was the development in Germany giving the Dual-Monarchy a "blank cheque" to pursue a military strategy that ensured Germany's backing.

Austro-Hungarian planning for operations against Serbia was not extensive and they ran into many logistical difficulties in mobilizing the army and beginning operations against the Serbs. They encountered problems with train schedules and mobilization schedules, which conflicted with agricultural cycles in some areas. When operations began in early August Austria-Hungary was unable to crush the Serbian armies as many within the monarchy had predicted. One difficulty for the Austro-Hungarians was that they had to divert many divisions north to counter advancing Russian armies. Planning for operations against Serbia had not accounted for possible Russian intervention, which the Austro-Hungarian army had assumed would be countered by Germany. However, the German army had long planned on attacking France before turning to Russia given a war with the Entente powers. (See: Schlieffen Plan) Poor communication between the two governments led to this catastrophic oversight.

Fighting in 1914[]

As a result, Austria-Hungary's war effort was damaged almost beyond redemption within a couple of months of the war beginning. The Serb army, which was coming up from the south of the country, met the Austrian army at the Battle of Cer beginning on August 12, 1914.

The Serbians were set up in defensive positions against the Austro-Hungarians. The first attack came on August 16, between parts of the 21st Austro-Hungarian division and parts of the Serbian Combined division. In harsh night-time fighting, the battle ebbed and flowed, until the Serbian line was rallied under the leadership of Stepa Stepanovic. Three days later the Austrians retreated across the Danube, having suffered 21,000 casualties against 16,000 Serbian casualties. This marked the first Allied victory of the war. The Austrians had not achieved their main goal of eliminating Serbia. In the next couple of months the two armies fought large battles at Drina (September 6 to November 11) and at Kolubara from November 16 to December 15.

In the autumn, with many Austro-Hungarians tied up in heavy fighting with Serbia, Russia was able to make huge inroads into Austria-Hungary capturing Galicia and destroying much of the Empire's fighting ability. It wasn't until October 1915 with a lot of German, Bulgarian, and Turkish assistance that Serbia was finally occupied, although the weakened Serbian army retreated to Corfu with Italian assistance and continued to fight against the central powers.

Yugoslav Committee, a political interest group formed by South Slavs from Austria-Hungary during World War I, aimed at joining the existing south Slavic nations in an independent state.[44] From this plan, a new kingdom eventually was born: The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians.

Montenegro declared war on 6 August 1914. Bulgaria, however, stood aside before eventually joining the Central Powers in 1915, and Romania joined the Allies in 1916. In 1916 the Allies sent their ill-fated expedition to Gallipoli in the Dardanelles, and in the autumn of 1916 they established themselves in Salonika, establishing front. However, their armies did not move from front until near end of the war, when they marched up north to free territories under rule of Central Powers.

Bulgaria[]

Bulgaria, the most populous of the Balkan states with 7 million people sought to acquire Macedonia but when it tried it was defeated in 1913 in the Second Balkan War. In 1914 Bulgaria stayed neutral. However its leaders still hoped to acquire Macedonia, which was controlled by an ally, Serbia. In 1915 joining the Central Powers seemed the best route.[45] Bulgaria mobilized a very large army of 800,000 men, using equipment supplied by Germany. The Bulgarian-German-Austrian invasion of Serbia in 1915 was a quick victory, but by the end of 1915 Bulgaria was also fighting the British and French—as well as the Romanians in 1916 and the Greeks in 1917. Bulgaria was ill-prepared for a long war; absence of so many soldiers sharply reduced agricultural output. Much of its best food was smuggled out to feed lucrative black markets elsewhere. By 1918 the soldiers were not only short of basic equipment like boots but they were being fed mostly corn bread with a little meat. Germany increasingly was in control, and Bulgarian relations with its ally the Ottoman Empire soured. The Allied offensive in September 1918, which failed in 1916 & 1917 was successful at Dobro Pole. Troops mutinied and peasants revolted, demanding peace. By month's end Bulgaria signed an armistice, giving up its conquests and its military hardware. The Czar abdicated and Bulgaria's war was over. The peace treaty in 1919 stripped Bulgaria of its conquests, reduced its army to 20,000 men, and demanded reparations of £100 million.[46]

Consequences of World War I[]

The war had enormous repercussions for the Balkan peninsula. People across the area suffered serious economic dislocation, and the mass mobilization resulted in severe casualties, particularly in Serbia where over 1.5 million Serbs died, which was approx. ¼ of the total population and over half of the male population. In less-developed areas World War I was felt in different ways: requisitioning of draft animals, for example, caused severe problems in villages that were already suffering from the enlistment of young men, and many recently created trade connections were ruined.

The borders of many states were completely redrawn, and the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later Yugoslavia, was created. Both Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire were formally dissolved. As a result, the balance of power, economic relations, and ethnic divisions were completely altered.

Some important territorial changes include:

- The addition of Transylvania and Eastern Banat to Romania

- The incorporation of Serbia, Montenegro, Slavonia, Croatia, Vojvodina, Carniola, part of Styria, most of Dalmatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

- Istria, Zadar, and Trieste became part of Italy,

Between World War I and World War II, in order to create nation-states the following population movements were seen:

- In the interwar period, almost 1.5 million Greeks were removed from Turkey; almost 700,000 Turks removed from Greece

- The 1919 Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine provided for the reciprocal emigration of ethnic minorities between Greece and Bulgaria. Between 92,000 and 102,000 Bulgarians were removed from Greece; 35,000 Greeks were removed from Bulgaria. Although no agreement on exchange of population between Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was ever reached because of the latter's adamant refusal to recognise any Bulgarian minority in its eastern regions, the number of refugees from Macedonia and Eastern Serbia to Bulgaria also exceeded 100,000. Between the two world wars, some 67,000 Turks emigrated from Bulgaria to Turkey on basis of bilateral agreements.

- Under the terms of 1940 Treaty of Craiova, 88,000 Romanians and Aromanians of Southern Dobruja were forced to move in Northern Dobruja and 65,000 Bulgarians of Northern Dobruja were forced to move in Southern Dobruja.

See also:

- Treaty of Trianon

- Little Entente

- League of Nations

- Aftermath of World War I

- Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) with an estimate of 250,000 casualties.[47]

World War II[]

World War II in the Balkans started from the Italian attempts to create an Italian empire. They invaded Albania in 1939 and annexed after just a week to the Kingdom of Italy. Then demanded Greece to surrender in October 1940. However, the defiance of the Greek prime minister Metaxas on 28 October 1940, started the Greco-Italian war. After seven months of hard fighting, with some of the first Allied victories and the Italians losing nearly one third of Albania, Germany intervened to save its ally. In 1941, it invaded Yugoslavia with the forces they later used against the Soviet Union.

After the fall of Sarajevo on 16 April 1941 to Nazi Germany, the Yugoslav provinces of Croatia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina were recreated as fascist satellite states, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska (NDH, the Independent State of Croatia). Croat-nationalist, Ante Pavelić was appointed leader. The Nazis effectively created the Handschar division and collaborated with Ustaše in order to combat the Yugoslav Partisans.

With help from Italy, they succeeded in conquering Yugoslavia within two weeks. They then joined forces with Bulgaria and invaded Greece from the Yugoslavian side. Despite Greek resistance, the Germans took advantage of the Greek army's presence in Albania against the Italians to advance in Northern Greece and consequently conquer the entire country within 3 weeks, with the exception of Crete. However, even with the fierce Cretan resistance, which cost the Nazis the bulk of their elite paratrooper forces, the island capitulated after 11 days of fighting.

On May 1 the Balkan frontiers were once again reshuffled, with the creation of several puppet states, such as Croatia and Montenegro, the Albanian expansion into Greece and Yugoslavia, Bulgarian annexation of territories in the Greek North, creation of a Vlach state in the Greek mountains of Pindus and the annexation of all the Ionian and part of the Aegean islands into Italy.

With the end of the war, the changes of the ethnic composition reverted to their original conditions and the settlers returned to their homelands, mainly the ones settled in Greece. An Albanian population of the Greek North, the Cams, were forced to flee their lands because they collaborated with the Italians. Their numbers were about 18 000 in 1944.

Aftermath of World War II[]

On January 7–9, 1945, Yugoslav authorities killed several hundred of declared Bulgarians in Macedonia as collaborators, in an event known as the "Bloody Christmas".

The Greek Civil War was fought between 1944 and 1949 in Greece between the armed forces of the Greek government, supported at first by Britain and later by the United States, against the forces of the wartime resistance against the German occupation, whose leadership was controlled by the Communist Party of Greece. Its goal was the creation of a Communist Northern Greece. It was the first time in the Cold War that hostilities led to a proxy war. In 1949, the partisans were defeated by the government forces.

Cold War[]

During the Cold War, most of the countries in the Balkans were ruled by Soviet-supported communist governments. The nationalism was not dead after World War II. Yugoslavia was not an isolated case of ethnic tension. For example: in Bulgaria, beginning in 1984, the Communist government led by Todor Zhivkov began implementing a policy of forced assimilation of the ethnic Turkish minority. Ethnic Turks were required to change their names to Bulgarian equivalents, or to leave the country. In 1989, a Turkish dissident movement was formed to resist these assimilationist measures. The Bulgarian government responded with violence and mass expulsions of the activists. In this repressive environment, over 300,000 ethnic Turks fled to neighboring Turkey.[48] However, despite being under communist governments, Yugoslavia (1948) and Albania (1961) fell out with the Soviet Union. After World War 2, communist plans of merging Albania and Bulgaria into Yugoslavia were created, but later nullified when Albania broke all relations with Yugoslavia, due to Tito breaking from the USSR. Marshal Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980), later rejected the idea of merging with Bulgaria, and instead sought closer relations with the West, later even creating the Non-Aligned Movement, which brought them closer ties with third world countries. Albania on the other hand gravitated toward Communist China, later adopting an isolationist position. The only non-communist countries were Greece and Turkey, which were (and still are) part of NATO.

Religious persecutions took place in Bulgaria, directed against the Christian Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches as well as the Muslim, Jewish and others in the country. Antagonism between the communist state and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church eased somewhat after Todor Zhivkov became Bulgarian Communist Party leader in 1956 for "its historic role in helping preserve Bulgarian nationalism and culture".[49]: 66

Post-Communism[]

The late 1980s and the early 1990s brought the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe. As westernization spread through the Balkans, many reforms were carried out that led to implementation of market economy and to privatization, among other capitalist reforms.

In Albania, Bulgaria and Romania the changes in political and economic system were accompanied by a period of political and economic instability and tragic events. The same was the case in most of former Yugoslav republics.

Yugoslav wars[]

The collapse of the Yugoslav federation was due to various factors in various republics that composed it. In Serbia and Montenegro, there were efforts of different factions of the old party elite to retain power under new conditions along, and an attempt to create Greater Serbia by keeping all Serbs in one state.[50] In Croatia and Slovenia, multi-party elections produced nationally inclined leadership that followed in the footsteps of their previous Communist predecessors and oriented itself towards capitalism and secession. Bosnia and Herzegovina was split between the conflicting interests of its Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks, while Macedonia mostly tried to steer away from conflicting situations.

An outbreak of violence and aggression came as a consequence of unresolved national, political and economic questions. The conflicts caused the death of many civilians. The real start of the war was a military attack on Slovenia and Croatia taken by Serb-controlled JNA. Before the war, JNA had started accepting volunteers driven by ideology of Serbian nationalists keen to realise their nationalist goals.[51]

The Ten-Day War in Slovenia in June 1991 was short and with few casualties. However, the Croatian War of Independence in the latter half of 1991 brought many casualties and much damage on Croatian towns. As the war eventually subsided in Croatia, the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina started in early 1992. Peace only came in 1995 after such events as the Srebrenica massacre, Operation Storm, Operation Mistral 2 and the Dayton Agreement, which provided for a temporary solution, but nothing was permanently resolved.

The economy suffered an enormous damage in all of Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the affected parts of Croatia. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia also suffered an economic hardship under internationally imposed economic sanctions. Also many large historical cities were devastated by the wars, for example Sarajevo, Dubrovnik, Zadar, Mostar, Šibenik and others.

The wars caused large population migrations, mostly involuntary. With the exception of its former republics of Slovenia and Macedonia, the settlement and the national composition of population in all parts of Yugoslavia changed drastically, due to war, but also political pressure and threats. Because it was a conflict fueled by ethnic nationalism, people of minority ethnicities generally fled towards regions where their ethnicity was in a majority. Since the Bosniaks had no immediate refuge, they were arguably hardest hit by the ethnic violence. The United Nations tried to create safe areas for the Bosniak populations of eastern Bosnia but in cases such as the Srebrenica massacre, the peacekeeping troops (Dutch forces) failed to protect the safe areas resulting in the massacre of thousands. The Dayton Accords ended the war in Bosnia, fixating the borders between the warring parties roughly to the ones established by the autumn of 1995. One immediate result of population transfers following the peace deal was a sharp decline in ethnic violence in the region. A number of commanders and politicians, notably Serbia's former president Slobodan Milošević, were put on trial by the United Nations' International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia for a variety of war crimes—including deportations and genocide that took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Croatia's former president Franjo Tuđman and Bosnia's Alija Izetbegović died before any alleged accusations were leveled at them at the ICTY. Slobodan Milošević died before his trial could be concluded.

Initial upsets on Kosovo did not escalate into a war until 1999 when the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) was bombarded by NATO for 78 days with Kosovo being made a protectorate of international peacekeeping troops. A massive and systematic deportation[citation needed] of ethnic Albanians took place during the Kosovo War of 1999, with over one million Albanians (out of a population of about 1.8 million) forced to flee Kosovo. This was quickly reversed from the aftermath.

2000 to present[]

Greece has been a member of the European Union since 1981. Greece is also an official member of the Eurozone, and the Western European Union. Slovenia and Cyprus have been EU members since 2004, and Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in 2007. Croatia joined the EU in 2013. North Macedonia also received candidate status in 2005 under its then provisional name Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, while the other Balkan countries have expressed a desire to join the EU but at some date in the future.

Greece has been a member of NATO since 1952. In 2004 Bulgaria, Romania and Slovenia became members of NATO. Croatia and Albania joined NATO in 2009.

In 2006, Montenegro declared independence from the state of Serbia and Montenegro.

On October 17, 2007 Croatia became a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for the 2008–2009 term, while Bosnia and Herzegovina became a non-permanent member for the 2010–2011 period.

Kosovo unliterally declared its independence from Serbia on February 17, 2008. To this day, it is partially recognized country.

Since the 2008 economic crisis, the former Yugoslav countries began to cooperate on levels that were similar to those in Yugoslavia. The term "Yugosphere" was coined by The Economist after a regional train service "Cargo 10" was created.

Overview of state histories[]

- Albania: The proto Albanians were likely a conglomerate of Illyrian tribes that resisted assimilation with latter waves of migrations into the Balkans. The Ardiaean kingdom, with its capital in Scodra, is perhaps the best example of a centralized, ancient Albanian state. After several conflicts with the Roman Republic, building up to the Third Illyrian War, Ardiaean as well as much of the Balkans was brought into Roman rule for centuries onward. Its last ruler, King Gentius, being taken captive in 167BC to Rome. After the Western Roman Empire's collapse the territory of what is today Albania remained under Byzantine control until the Slavic migrations. It was integrated into the Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century. The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state formed in the Middle Ages, as the Principality of Arbër and the Kingdom of Albania. The first records of the Albanian people as a distinct ethnicity also date to this period. Most of the coast of Albania was controlled by the Republic of Venice from the 10th century until the arrival of the Ottoman Turks (Albania Veneta), while the interior was ruled by Byzantians, Bulgarians or Serbs. Despite the long resistance of Skanderbeg, the area was conquered in the 15th century by the Ottoman Empire and remained under their control as part of the Rumelia province until 1912, when the first independent Albanian state was declared. The formation of an Albanian national consciousness dates to the later 19th century and is part of the larger phenomenon of rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: The territory was divided between Croatia and Serbia in the Early Middle Ages. "Bosnia" itself was a Serbian polity according to the DAI. Bosnia, along with other territories, became part of Duklja in the 11th century. In time, Bosnia became separated under its own ruler. After 1101, Bosnia was detached from Duklja, and subsequently came under Hungarian suzerainty, as was the case with Croatia. Byzantine rule interrupted Hungarian rule, and under Byzantine suzerainty, the Banate of Bosnia came to existence. The later ban became a Hungarian nominal vassal. The Bosnian Church was a Christian church in Bosnia deemed heretical, which some rulers were adherents of. The rulers empowered themselves through trade with Ragusa, and gained lands from Serbia (Herzegovina). Bosnia reached its zenith under the rule of Tvrtko who took more lands, including parts of Dalmatia, and crowned himself as king in 1377. After the Ottoman conquest of Serbia, Bosnia followed. The Sanjak of Bosnia was established, and the local population was subject of Islamization during the following centuries by the Ottoman Empire which guaranteed more rights to Muslims. The ethnic tensions that arose in modern times stem from this religious division. Austria-Hungary took over Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878 and annexed it in 1908. It was subsequently joined to Yugoslavia. After the Bosnian War, the state received international independence for the first time.

- Bulgaria: The Bulgars came from northeast and settled the Balkans after 680. They subsequently were absorbed by the numerous local Slavs. Bulgaria became officially Christian in the late 9th century. The Cyrillic was developed in the Preslav Literary School in Bulgaria in the late 9th - beginning of the 10th century. The Bulgarian Church was recognized as autocephalous during the reign of Boris I of Bulgaria and became Patriarchate during tsar Simeon the Great, who greatly expanded the state over Byzantine territory. In 1018, Bulgaria became an autonomous theme in the Roman empire until the restoration by the Asen dynasty in 1185. In the 13th century Bulgaria was once again one of the powerful states in the region. By 1422 all Bulgarian lands south of the Danube became part of the Ottoman state, however local control remained in Bulgarian hands in many places. North of the Danube, Bulgarian Boyars continued to rule for the next three centuries. Bulgarian language continued to be used as the official language north of the Danube until the 19th century.

- Croatia: Following the settlement of Slavs in the Roman provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia, Croat tribes established two duchies. They were surrounded by the Franks (and later Venetians) and Avars (and later Magyars), while Byzantines tried to maintain control of the Dalmatian coast. The Kingdom of Croatia was founded in 925. It covered parts of Dalmatia, Bosnia and Pannonia. The state came under Papal (Catholic) influence. In 1102, Croatia entered a union with Hungary. Croatia was still considered a separate, albeit a vassal, kingdom. With the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans, Croatia fell after successive battles, finalized in 1526. The remaining part then received Austrian rule and protection. Much of its border areas became part of the Military Frontier, inhabited and protected by Serbs, Vlachs, Croats and Germans since the area had previously become deserted. Croatia joined Yugoslavia in 1918–20. Independence was retained following the Croatian War.

- Greece: Greeks, an ancient ethnic group (Athenians, Spartans, Peloponnesians, Thessalians, Macedonians etc.) and the oldest civilization of Europe[52] and then the Mycenaean civilization on the mainland (1600–1100 BC).[52] The scope of Greek habitation and rule has varied throughout the ages and as a result the history of Greece is similarly elastic in what it includes.

- Montenegro: In the 10th century, there were three principalities on the territory of Montenegro: Duklja, Travunia, and Serbia ("Raška"). In the mid-11th century Duklja attained independence through a revolt against the Byzantines; the Vojislavljević dynasty ruled as Serbian monarchs, having taken over territories of the former Serbian Principality. It then came under the rule of the Nemanjić dynasty of Serbia. By the 13th century, Zeta had replaced Duklja when referring to the realm. In the late 14th century, southern Montenegro (Zeta) came under the rule of the Balšić noble family, then the Crnojević noble family, and by the 15th century, Zeta was more often referred to as Crna Gora (Venetian: monte negro). Large portions fell under the control of the Ottoman Empire from 1496 to 1878. The Republic of Venice dominated the coasts of today's Montenegro from 1420 to 1797; the area around the Kotor became part of Venetian Albania. Parts were also briefly controlled by the First French Empire and Austria-Hungary in the 19th century. From 1696 until 1851 the metropolitans of Cetinje (of the House of Petrović-Njegoš) ruled the polity of Montenegro (Old Montenegro) alongside tribal rulers. The Petrović-Njegoš transformed Montenegro into a principality in 1851 and ruled until 1918. Independence of the Principality of Montenegro was received in 1878. From 1918, it was a part of Yugoslavia. On the basis of an independence referendum held on 21 May 2006, Montenegro became independent.

- North Macedonia: North Macedonia officially celebrates 8 September 1991 as Independence day (Macedonian: Ден на независноста, Den na nezavisnosta), with regard to the referendum endorsing independence from Yugoslavia, albeit legalising participation in future union of the former states of Yugoslavia.[53] The anniversary of the start of the Ilinden Uprising (St. Elijah's Day) on 2 August is also widely celebrated on an official level as the Day of the Republic.

- Serbia: Following the settlement of Slavs, the Serbs established several principalities, as described in the DAI. Serbia was elevated to a kingdom in 1217, and an empire in 1346. By the 16th century, the entire territory of modern-day Serbia was annexed by the Ottoman Empire, at times interrupted by the Habsburg Empire. In the early 19th century the Serbian Revolution re-established the Serbian state, pioneering in the abolition of feudalism in the Balkans. Serbia became the region's first constitutional monarchy, and subsequently expanded its territory in the wars. The former Habsburg crownland of Vojvodina united with the Kingdom of Serbia in 1918. Following World War I, Serbia formed Yugoslavia with other South Slavic peoples which existed in several forms up until 2006, when the country retrieved its independence.

Cultural history[]

Albanian culture[]

Byzantine culture[]

Bulgarian culture[]

Serbian culture[]

Ottoman culture[]

Eastern Orthodoxy[]

See also[]

- History of Albania

- History of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History of Bulgaria

- History of Croatia

- History of Greece

- History of Kosovo

- History of North Macedonia

- History of Montenegro

- History of the Republic of Venice

- History of Romania

- History of Serbia

- History of Slovenia

- History of Turkey

- History of Yugoslavia

- History of Europe

- Historical regions of the Balkan Peninsula

- Rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

- International relations (1814–1919)

- List of empires

- List of medieval great powers

- List of largest empires

- Cultural area

References[]

- ^ Jelavich 1983a, p. 1-3.

- ^ Mazower 2007

- ^ Jovanović, Jelena; Power, Robert C.; de Becdelièvre, Camille; Goude, Gwenaëlle; Stefanović, Sofija (2021-01-01). "Microbotanical evidence for the spread of cereal use during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in the Southeastern Europe (Danube Gorges): Data from dental calculus analysis". Journal of Archaeological Science. 125: 105288. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105288. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Bonsall, C.; Cook, G. T.; Hedges, R. E. M.; Higham, T. F. G.; Pickard, C.; Radovanović, I. (2004). "Radiocarbon and Stable Isotope Evidence of Dietary Change from the Mesolithic to the Middle Ages in the Iron Gates: New Results from Lepenski Vir". Radiocarbon. 46 (1): 293–300. doi:10.1017/S0033822200039606. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ The Illyrians (The Peoples of Europe) by John Wilkes,ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9,1996,page 39: "... the other hand, the beginnings of the Iron Age around 1000 BC is held to coincide with the formation of the historical Illyrian peoples. ..."

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, N. G. L. Hammond, and E. Sollberger,1982,page 53,"... Yet we cannot identify the Thracians at that remote period, because we do not know for certain whether the Thracian and Illyrian tribes had separated by then. It is safer to speak of Proto-Thracians from whom there developed in the Iron Age ..."

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth,ISBN 0-19-860641-9,"page 1515,"The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- ^ Joseph Roisman,Ian Worthington A Companion to Ancient Macedonia pp 342–345 John Wiley & Sons, 7 jul. 2011 ISBN 144435163X

- ^ Xenophon (2005-09-08). The Expedition of Cyrus. ISBN 9780191605048. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ The Illyrians. John Wilkes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2011-07-07). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. ISBN 9781444351637. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Timothy Howe, Jeanne Reames. Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honor of Eugene N. Borza (original from the Indiana University) Regina Books, 2008 ISBN 978-1930053564 p 239

- ^ "Persian influence on Greece (2)". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 44

- ^ Joseph Roisman,Ian Worthington A Companion to Ancient Macedonia p. 344 John Wiley & Sons, 7 jul. 2011 ISBN 144435163X

- ^ The Serbs, Chapter 1 -Ancient Heritage, S M Cirkovic

- ^ Orlin, Eric (19 November 2015). Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions. Routledge. p. 287. ISBN 9781134625529.

- ^ MacMullen, Ramsay; Lane, Eugene (1 January 1992). Paganism and Christianity, 100-425 C.E.: A Sourcebook. Fortress Press. p. 219. ISBN 9781451407853.

- ^ Takacs, Sarolta Anna; Cline, Eric H. (17 July 2015). The Ancient World. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 9781317458395.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1 January 2008). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Cosimo, Inc. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-60520-122-1.

- ^ Mapping the Jewish communities of the Byzantine Empire

- ^ Laurentiu, R. At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities, pp. 109, 219. 2010

- ^ R. Bonfil et al., Jews in Byzantium: Dialectics of Minority and Majority Cultures, p. 127-ff. 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hupchick 2004, p. ?.

- ^ David Christian-A history of Russia, Central Asia, and Mongolia, p.280

- ^ Elian, Alexandru and Tanasoca, Nicolae-Serban (1975). Fontes Historiae Daco-Romanae, Saec. XI-XIV, Editura Academiei RSR, Bucuresti,1975, note 91 on p.117.

- ^ Davies, Norman (1997). Europe. A History. Oxford University press. ISBN 954-427-663-7.

- ^ Curta, Florin (31 August 2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle ages 500 - 1200. ISBN 0-521-81539-8.

- ^ Rashev, Rasho (2008). Българската езическа култура VII -IX в. Класика и стил. ISBN 9789543270392.

- ^ Розата на Балканите, Иван Илчев, т.1, ISBN 9786190204244

- ^ The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, John Van Antwerp Fine, University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0-472-08260-4, p. 12

- ^ History of the Byzantine Empire, 324-1453, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Vasilʹev, Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1952, ISBN 0-299-80926-9, p. 442.

- ^ Richard Cowen, The importance of salt Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gail Warrander, Verena Knau, Kosovo, 2nd: The Bradt Travel Guide.

- ^ Edoardo Corradi, Rethinking Islamized Balkans, Balkan Social Science Review, vol. 8, December 2016, p. 121 – 139.

- ^ Kitromilides, Paschalis M. 1996. "’Balkan mentality’: history, legend, imagination", in: Nations and Nationalism, 2 (2), pp. 163–191.

- ^ Franklin L. Ford, Europe: 1780–1830 (1970) pp 39–41

- ^ Ford, Europe: 1780–1830 (1970) pp 39–41

- ^ A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 (1954) pp 228–54

- ^ Jerome L. Blum, et al. The European World: A History (1970) p 841

- ^ Christopher Clark (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. pp. 45, 559. ISBN 9780062199225.

- ^ Richard C. Hall, The Balkan Wars 1912-1913: Prelude to the First World War (2000)

- ^ "Black Hand | Definition, History, & Facts".

- ^ Norka Machiedo Mladinić (June 2007). "Prilog proučavanju djelovanja Ivana Meštrovića u Jugoslavenskom odboru" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). 39 (1). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

- ^ Tucker, The European powers in the First World War (1996). pp 149–52

- ^ Richard C. Hall, "Bulgaria in the First World War," Historian, (Summer 2011) 73#2 pp 300–315 online

- ^ "Secondary Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century" Archived May 7, 2009, at WebCite

- ^ Ethnic Cleansing and the Normative Transformation of International Society Archived March 19, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Department of State Bulletin. Office of Public Communication, Bureau of Public Affairs. 1986.

- ^ Ethnic cleansed Great Serbia

- ^ "Institute for War and Peace Reporting". Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. September 2009. p. 1458. ISBN 978-0-7614-7902-4. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Greece was home to the earliest European civilizations, the Minoan civilization of Crete, which developed around 2000 BC, and the Mycenaean civilization on the Greek mainland, which emerged about 400 years later. The ancient Minoan

- ^ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p. 1278 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

Sources and further reading[]

- Secondary sources

- Calic, Marie-Janine. The Great Cauldron: A History of Southeastern Europe (2019) excerpt

- Carter, Francis W., ed. An historical geography of the Balkans (Academic Press, 1977).

- Castellan, Georges (1992). History of the Balkans: From Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-222-4.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Forbes, Nevill, et al. The Balkans : a history of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Rumania, Turkey (1915) summary histories by scholars online free

- Gerolymatos, André (2002). The Balkan wars: conquest, revolution, and retribution from the Ottoman era to the twentieth century and beyond. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465027323. OCLC 49323460.

- Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-2011. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-61099-2.

- Hall, Richard C. ed. War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia (2014)

- Hatzopoulos, Pavlos. Balkans Beyond Nationalism and Identity: International Relations and Ideology (IB Tauris, 2007).

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2004) [2002]. The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6417-5.

- Hösch, Edgar (1972). The Balkans: a short history from Greek times to the present day. Crane, Russak. ISBN 978-0-8448-0072-1.

- Jeffries, Ian, and Robert Bideleux. The Balkans: A Post-Communist History (2007).

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983a). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274586.

- Jelavich, Barbara. History of the Balkans, Vol. 1: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (1983)

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983b). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274593.

- Mazower, Mark (2007). The Balkans: A Short History. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-43196-7.

- McCarthy, Justin (2010). Population History of the Middle East and the Balkans. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-61719-105-3.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453 (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43991-6.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2014). A History of the Balkans 1804-1945. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-90016-0.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. Serbia: The history of an idea. (NYU Press, 2002).

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. The improbable survivor: Yugoslavia and its problems, 1918-1988 (1988). online free to borrow

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. Tito—Yugoslavia's great dictator : a reassessment (1992) online free to borrow

- Schevill, Ferdinand. The History of the Balkan Peninsula; From the Earliest Times to the Present Day (1966)

- Stanković, Vlada, ed. (2016). The Balkans and the Byzantine World before and after the Captures of Constantinople, 1204 and 1453. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-1326-5.

- Stavrianos, L.S. The Balkans Since 1453 (1958), major scholarly history; online free to borrow

- Sumner, B. H. Russia and the Balkans 1870-1880 (1937)

- Wachtel, Andrew Baruch (2008). The Balkans in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988273-1.

Historiography and memory[]

- Cornelissen, Christoph, and Arndt Weinrich, eds. Writing the Great War - The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present (2020) free download; full coverage for Serbia and major countries.

- Fikret Adanir and Suraiya Faroqhi. The Ottomans and the Balkans: A Discussion of Historiography (2002) online

- Bracewell, Wendy, and Alex Drace-Francis, eds. Balkan Departures: Travel Writing from Southeastern Europe (2010) online

- Fleming, Katherine Elisabeth. "Orientalism, the Balkans, and Balkan historiography." American historical review 105.4 (2000): 1218-1233. online

- Kitromilides, Paschalis. Enlightenment, Nationalism, Orthodoxy: Studies in the Culture and Political Thought of South-eastern Europe (Aldershot, 1994).

- Tapon, Francis (2012). The Hidden Europe: What Eastern Europeans Can Teach Us. WanderLearn Press. ISBN 9780976581222.

- Todorova, Maria. Imagining the Balkans (1997). excerpt

- Uzelac, Aleksandar. "The Ottoman Conquest of the Balkans. Interpretations and Research Debates." Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 71#2 (2018), p. 245+. online

Primary sources[]

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472061860.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of the Balkans. |

- History of the Balkans

- Southeastern Europe

- Balkans