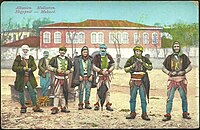

Albanian tribes

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

The Albanian tribes (Albanian: fiset shqiptare) form a historical mode of social organization (farefisní) in Albania and the southwestern Balkans characterized by a common culture, often common patrilineal kinship ties tracing back to one progenitor and shared social ties. The fis (definite Albanian form: fisi; commonly translated as "tribe", also as "clan" or "kin" community) stands at the center of Albanian organization based on kinship relations, a concept which can be found among southern Albanians also with the term farë (definite Albanian form: fara).

Inherited from ancient Illyrian social structures, Albanian tribal society emerged in the early Middle Ages as the dominant form of social organization among Albanians.[1][2] The development of feudalism came to both antagonize it, but also slowly integrate aspects of it in Albanian feudal society as most noble families themselves came from these tribes and depended on their support. This process stopped after the Ottoman conquest of Albania and the Balkans in the late 15th century and was followed by a process of strengthening of the tribe (fis) as a means of organization against Ottoman centralization particularly in the mountains of northern Albania and adjacent areas of Montenegro.

It also remained in a less developed system in southern Albania[3] where large feudal estates and later trade and urban centres began to develop at the expense of tribal organization. One of the most particular elements of the Albanian tribal structure is its dependence on the Kanun, a code of Albanian oral customary laws.[1] Most tribes engaged in warfare against external forces like the Ottoman Empire. Some also engaged in limited inter-tribal struggle for the control of resources.[3]

Until the early years of the 20th century, the Albanian tribal society remained largely intact until the rise to power of communist regime in 1944, and is considered as the only example of a tribal social system structured with tribal chiefs and councils, blood feuds and oral customary laws, surviving in Europe until the middle of the 20th century.[3][4][5]

Terminology[]

Fundamental terms that define Albanian tribal structure are shared by all regions. Some terms may be used interchangeably with the same semantic content and other terms have a different content depending on the region. No uniform or standard classification exists as societal structure showed variance even within the same general area. The term fis is the central concept of Albanian tribal structure. The fis is a community whose members are linked to each other as kin through the same patrilineal ancestry and live in the same territory. It has been translated in English as tribe or clan.[6] Thus, fis refers both to the kinship ties that bond the community and the territorialization of that community in a region exclusively used in a communal manner by the members of the fis. In contrast, bashkësi (literally, association) refers to a community of the same ancestry which has not been established territorially in a given area which is considered its traditional home region.

It is further divided into fis i madh and fis i vogël. Fis i madh refers to all members of the kin community that live in its traditional territory, while fis i vogël refers to the immediate family members and their cousins (kushëri).[7] In this sense, it is sometimes used synonymously with vëllazëri or vllazni in Geg Albanian. This term refers to all families that trace their origin to the same patrilineal ancestor. Related families (familje) are referred to as of one bark/pl. barqe (literally, belly). As some tribes grew in number, a part of them settled in new territory and formed a new fis that may or may not have held the same name as the parental group. The concept of farefisni refers to the bonds between all communities that stem from the same fis. Farë literally means seed. Among southern Albanians, it is sometimes used as a synonym for fis, which in turn is used in the meaning of fis i vogël.

The term bajrak refers to an Ottoman military institution of the 17th century. In international bibliography of the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was often mistakengly equated with the fis as both would sometimes cover the same geographical area. The result of this mistake was the portrayal of bajrak administrative divisions and other regions as fis in early anthropological accounts of Albania, although there were bajraks in which only a small part or none at all constituted a fis.[8]

Organisation[]

Northern Albanians[]

Among Gheg Malësors (highlanders) the fis (clan), is headed by the oldest male (kryeplak) and formed the basic unit of tribal society.[9][10] The governing councils consist of elders (pleknit, singular: plak). The idea of law administration is so closely related to the "old age", that "to arbitrate" is me pleknue, and plekní means both "seniority" and "arbitration".[10] The fis is divided into a group of closely related houses called mehala, and the house (shpi). The head of mehala is the krye (lit. "head", pl. krenë/krenët), while the head of the house is the zoti i shpis ("the lord of the house"). A house may be composed by two or three other houses with property in common under one zot.[11]

A political and territorial unit consisting of several clans was the bajrak (standard, banner).[9] The leader of a bajrak, whose position was hereditary, was referred to as bajraktar (standard bearer).[9] Several bajraks composed a tribe, which was led by a man from a notable family, while major issues were decided by the tribe assembly whose members were male members of the tribe.[12][9] The Ottomans implemented the bayraktar system within northern Albanian tribes, and granted some privileges to the bayraktars (banner chieftains) in exchange for their obligation to mobilize local fighters to support military actions of the Ottoman forces.[13][14] Those privileges also entailed Albanian tribesmen to pay no taxes and were excluded from military conscription in return for military service as irregular troops however few served in that capacity.[14] Malisors viewed Ottoman officials as a threat to their tribal way of living and left it to their bajraktars to deal with the Ottoman political system.[15] Officials of the late Ottoman period noted that Malisors preferred their children learn use of a weapon and refused to send them to government schools that taught Turkish which were viewed as forms of state control.[16] Most Albanian Malisors were illiterate.[15]

Southern Albanians[]

In southern Albania, the social system is based on the house (shpi or shtëpi) and the fis, consisting of a patrilineal kinship group and an exogamous unit composed by members with some property in common.[17] The patrilineal kinship ties are defined by the concept of "blood" (gjak) also implying physical and moral characteristics, which are shared by all the members of a fis.[17] The fis generally consists of three or four related generations, meaning that they have a common ancestor three or four generations ago, while the tribe is called fara or gjeri, which is much smaller than a northern Albanian fis.[18] The members of a fara know that they have a common ancestor who is the eponymos founder of the village.[19] The political organization is communal, that is, every neighbourhood send a representing elder (plak), to the governing council of the village (pleqësi), who elect the head of the village (kryeplak).[20]

The Albanian term farë (definite form: fara) means in general "seed" and "progeny"; but, while in northern Albania it has no legal use, in southern Albania it was used legally instead of the term fis of the northerners until the beginning of the 19th century, both in the sense of a politically autonomous tribe and in that of 'brotherhood' (Gheg Alb. vëllazni; Tosk Alb. vëllazëri; or Alb. bark, "belly"). Early attestations of these forms of social organization among southern Albanians are reported by Leake and Pouqueville when describing the traditional organization of Suli (practiced between 1660 and 1803), Epirus and southern Albania in general (until the beginning of the 19th century). Pouqueville in particular reported that each village (Alb. katun) and each town was some kind of autonomous republic composed by the farë in the sense of brotherhoods. In other accounts he also reported the 'great farë' in the sense of tribes, which had their polemarchs, and these chiefs had their boluk-bashis (platoon commander),[21] which were the analogues of the northern fis, the bajraktarë and the krenë (chieftains) of the vëllazni, respectively.[22]

Unlike the northern Albanian tribes, the lineage groups of southern Albanians did not inhabit a closed region, but they constructed ethnographic islands that were located on mountains and surrounded by a farming environment. One of the centres of these lineage societies was based in Labëria in the central mountains of southern Albania. A second centre was based in Himara in southwest Albania. A third centre was based in the Suli region, which was located far south in the middle of a Greek population. Tendency to build segmentary lineage organizations of these mountain pastoral communities increased with the degree of their isolation, which caused the loss of the tribal organization of the Albanian highlanders in southern Albania and northern Greece since the 15th century, during the period of the Ottoman dominion. Afterwards these lineage segments increasingly became in the social organization the basic political, economic, religious, and predatory units.[18]

According to Pouqueville these forms of social organizations disappeared with the dominion of the Ottoman Albanian ruler Ali Pasha, and ended definetly in 1813.[24] In the Pashalik of Yanina, in addition to the Sharia for Muslims and Canon for Christians, Ali Pasha enforced his own laws, allowing only in rare cases the usage of local Albanian tribal customary laws. After annexing Suli and Himara into his semi-independent state in 1798, he tried to organize the judiciary in every city and province according to the principle of social equality, enforcing his laws for the entire population, Muslims and Christians. To limit blood feud killings, Ali Pasha replaced blood feuds (Alb. gjakmarrje) with other punishments such as blood payment or expulsion up to the death penalty.[25] Ali Pasha also reached an agreement with the Kurveleshi population, not to trespass their territories, which at that time were larger than the area they inhabit today.[26] Since the 18th century and continuously, blood feuds and their consequences in Labëria have been limited principally by the councils of elders.[25]

The mountain region of Kurveleshi represents the last example of a tribal system among southern Albanians,[27][28] which was regulated by the Code of Zuli (Kanuni i Papa Zhulit/Zulit or Kanuni i Idriz Sulit).[28] In Kurvelesh the names of the villages were built as collective pluralia, which designated the tribal settlements. For instance, Lazarat can be considered as a toponym that was originated to refer to the 'descendants of Lazar'.[29]

Culture[]

Autonomy, Kanun and Gjakmarrja[]

The northern Albanian tribes are fiercely proud of the fact that they have never been completely conquered by external powers, in particular by the Ottoman Empire. This fact is raised on the level of historical and heritage orthodoxy among the members of the tribes. In the 18th century the Ottomans instituted the system of bajrak military organization in northern Albania and Kosovo. From the Ottoman perspective, the institution of the bajrak had multiple benefits. Although it recognized a semi-autonomous status in communities like Hoti, it could also be used to stabilize the borderlands as these communities in their new capacity would defend the borders of the empire, as they saw in them the borders of their own territory. Furthermore, the Ottomans considered the office of head bajraktar as a means that in times of rebellion could be used to divide and conquer the tribes by handing out privileges to a select few. On the other hand, autonomy of the borderlands was also a source of conflict as the tribes tried to increase their autonomy and minimize involvement of the Ottoman state. Through a circular series of events of conflict and renegotiation a state of balance was found between Ottoman centralization and tribal autonomy. Hence, the Ottoman era is marked by both continuous conflict and a formalization of socio-economic status within Ottoman administration.[13]

Members of the tribes of northern Albania believe their history is based on the notions of resistance and isolationism.[30] Some scholars connect this belief with the concept of "negotiated peripherality". Throughout history the territory northern Albanian tribes occupy has been contested and peripheral so northern Albanian tribes often exploited their position and negotiated their peripherality in profitable ways. This peripheral position also affected their national program which significance and challenges are different from those in southern Albania.[31] Such peripheral territories are zones of dynamic culture creation where it is possible to create and manipulate regional and national histories to the advantage of certain individuals and groups.[32]

Malisor society used tribal law and participated in the custom of bloodfeuding.[33] Ottoman control mainly existed in the few urban centres and valleys of northern Albania and was minimal to almost non-existent in the mountains, where Malisors lived an autonomous existence according to kanun (tribal law) of Lek Dukagjini.[34] At the same time Western Kosovo was also an area where Ottoman rule among highlanders was minimal to non-existent and government officials would ally themselves with local power holders to exert any form of authority.[35] Western Kosovo was dominated by the Albanian tribal system where Kosovar Malisors settled disputes among themselves through their mountain law.[35] In period without stable state control the tribe trialed its members. The usual punishments were fines, exile or disarmament. The house of the exiled member of the tribe would be burned. Disarmament was regarded as the most embarrassing verdict.[36]

The Law of Lek Dukagjini (kanun) was named after a medieval prince Lekë Dukagjini from the fifteenth century who ruled in northern Albania and codified the customary laws of the highlands.[15] Albanian tribes from the Dibra region governed themselves according to the Law of Skanderbeg (kanun), named after a fifteenth century warrior who fought the Ottomans.[37] Disputes would be solved through tribal law within the framework of vendetta or blood feuding and the activity was widespread among the Malisors.[38] In situations of murder tribal law stipulated the principle of koka për kokë (head for a head) where relatives of the victim are obliged to seek gjakmarrja (blood vengeance).[15] Nineteen percent of male deaths in İşkodra vilayet and 600 fatalities per year in Western Kosovo were from murders caused by vendetta and blood feuding during the late Ottoman period.[39]

Besa[]

Besa is a word in the Albanian language meaning "pledge of honour", "to keep the promise".[40] Besa is an important institution within the tribal society of the Albanian Malisors, and is one of the moral principles of the Kanun.[37][41] Albanian tribes swore oaths to jointly fight against the government and in this aspect the besa served to uphold tribal autonomy.[37] The besa was used toward regulating tribal affairs both between and within tribes.[37] The Ottoman government used the besa as a way to co-opt Albanian tribes in supporting state policies or to seal agreements.[37]

During the Ottoman period, the besa would be cited in government reports regarding Albanian unrest, especially in relation to the tribes.[42] The besa formed a central place within Albanian society in relation to generating military and political power.[43] Besas held Albanians together, united them and would wane when the will to enforce them dissipated.[44] In times of revolt against the Ottomans by Albanians, the besa functioned as a link among different groups and tribes.[44]

Besa is an important part of personal and familial standing and is often used as an example of "Albanianism". Someone who breaks his besa may even be banished from his community.[citation needed]

Geography[]

The Malisors lived in three geographical regions within northern Albania.[45] Malësia e Madhe (great highlands) contained five large tribes with four (Hoti, Kelmendi, Shkreli, Kastrati) having a Catholic majority and Muslim minority with Gruda evenly split between both religions.[45] Within Malësia e Madhe there were an additional seven small tribes.[45] During times of war and mobilisation of troops, the bajraktar (chieftain) of Hoti was recognised by the Ottoman government as leader of all forces of the Malësia e Madhe tribes having collectively some 6,200 rifles.[45]

Malësia e Vogël (small highlands) with seven Catholic tribes such as the Shala with 4 bajaraktars, Shoshi, Toplana and Nikaj containing some 1,250 households with a collective strength of 2,500 men that could be mobilised for war.[45] Shoshi had a distinction in the region of possessing a legendary rock associated with Lekë Dukagjini.[45]

The Mirdita region which was also a large powerful devoutly Catholic tribe with 2,500 households and five bajraktars that could mobilize 5,000 irregular troops.[45] A general assembly of the Mirdita met often in Orosh to deliberate on important issues relating to the tribe.[45] The position of hereditary prince of the tribe with the title Prenk Pasha (Prince Lord) was held by the Gjonmarkaj family.[45] Apart from the princely family the Franciscan Abbot held some influence among the Mirdita tribesmen.[45]

The government estimated the military strength of Malisors in İşkodra sanjak as numbering over 30,000 tribesmen and Ottoman officials were of the view that the highlanders could defeat Montenegro on their own with limited state assistance.[46]

In Western Kosovo, the Gjakovë highlands contained eight tribes that were mainly Muslim and in the Luma area near Prizren there were five tribes, mostly Muslim.[35] Other important tribal groupings further south include the highlanders of the Dibra region known as the "Tigers of Dibra".[47]

Among the many religiously mixed Catholic-Muslim tribes and one Muslim-Orthodox clan, Ottoman officials noted that tribal loyalties superseded religious affiliations.[45] In Catholic households there were instances of Christians who possessed four wives, marrying the first spouse in a church and the other three in the presence of an imam, while among Muslim households the Islamic tradition of circumcision was ignored.[45]

History[]

Late Ottoman period[]

During the Great Eastern Crisis, Prenk Bib Doda, hereditary chieftain of Mirdita initiated a rebellion in mid-April 1877 against government control and the Ottoman Empire sent troops to put it down.[48] Montenegro attempted to gain support from among the Malisors even though it lacked religious or ethnic links with the Albanian tribesmen.[49] Amidst the Eastern Crisis and subsequent border negotiations Italy suggested in April 1880 for the Ottoman Empire to give Montenegro the Tuz district containing mainly Catholic Gruda and Hoti populations which would have left the tribes split between both countries.[50] With Hoti this would have left an additional problem of tensions and instability due to the tribe having precedence by tradition over the other four tribes during peace and war.[50] The tribes affected by the negotiations swore a besa (pledge) to resist any reduction of their lands and sent telegrams to surrounding regions for military assistance.[50]

During the late Ottoman period Ghegs often lacked education and integration within the Ottoman system, while they had autonomy and military capabilities.[38] Those factors gave the area of Gegënia an importance within the empire that differed from Toskëria.[38] Still many Ottoman officers thought that Ghegs, in particular the highlanders were often a liability instead of an asset for the state being commonly referred to as "wild" (Turkish: vahşi) or a backward people that lived in poverty and ignorance for 500 years being hostile to civilisation and progress.[51] In areas of Albania were Malisors lived, the empire only posted Ottoman officers who had prior experience of service in other tribal regions of the state like Kurdistan or Yemen that could bridge cultural divides with Gheg tribesmen.[52]

Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Ottoman officials posted to Albanian populated lands and some Albanians strongly disproved of blood feuding viewing it as inhumane, uncivilised and an unnecessary waste of life that created social disruption, lawlessness and economic dislocation.[53] To resolve disputes and clamp down on the practice the Ottoman state addressed the problem directly by sending Blood Feud Reconciliation Commissions (musalaha-ı dem komisyonları) that produced results with limited success.[42] In the late Ottoman period, due to the influence of Catholic Franciscan priests some changes to blood feuding practices occurred among Albanian highlanders such as guilt being restricted to the offender or their household and even one tribe accepting the razing of the offender's home as compensation for the offense.[42] Ottoman officials were of the view that violence committed by Malisors in the 1880s-1890s was of a tribal nature not related to nationalism or religion.[33] They also noted that Albanian tribesmen who identified with Islam did so in name only and lacked knowledge of the religion.[54]

In the aftermath of the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 the new Young Turk government established the Commissions for the Reconciliation of Blood Feuds that focused on the regions such as İpek (Pejë) and Prizren.[55] The commissions sentenced Albanians who had participated in blood feud killing and the Council of Ministers allowed them to continue their work in the provinces until May 1909.[55] After the Young Turk Revolution and subsequent restoration of the Ottoman constitution, the Hoti, Shala, Shoshi and Kastati tribes made a besa (pledge) to support the document and to stop blood feuding with other tribes until November 6, 1908.[56] The Albanian tribes showing sentiments of enthusiasm however had little knowledge of what the constitution would do for them.[57]

During the Albanian revolt of 1910, Malisors such as the Shala tribe fought against Ottoman troops that were sent to quell the uprising, disarm the population by collecting guns, and replace the Law of Lek with state courts and laws.[58] Malisors instead planned further resistance and Albanian tribes living near the border fled into Montenegro while negotiating terms with the Ottomans for their return.[58] The Ottoman commander Mahmud Shevket involved in military operations concluded that the bajraktars had become Albanian nationalists and posed a danger to the empire when compared to previous uprisings.[59]

The Albanian revolt of 1911 was begun during March by Catholic Albanian tribesmen after they returned from exile in Montenegro.[60] The Ottoman government sent 8,000 troops to quell the uprising and ordered that tribal chieftains would need to stand trial for leading the rebellion.[60] During the revolt, Terenzio Tocci, an Italo-Albanian lawyer gathered the Mirditë chieftains on 26/27 April 1911 in Orosh and proclaimed the independence of Albania, raised the flag of Albania and declared a provisional government.[58] After Ottoman troops entered the area to put down the rebellion, Tocci fled the empire abandoning his activities.[61] On 23 June 1911 Albanian Malisors and other revolutionaries gathered in Montenegro and drafted the Greçë Memorandum demanding Albanian sociopolitical and linguistic rights with signatories being from the Hoti, Gruda, Shkreli, Kelmendi and Kastrati tribes.[60] In later negotiations with the Ottomans, an amnesty was granted to the tribesmen with promises by the government to build roads and schools in tribal areas, pay wages of teachers, limit military service to the Istanbul and Shkodër areas, right to carry weapons in the countryside but not in urban areas, the appointment of bajraktars relatives to certain administrative positions and compensate Malisors with money and food arriving back from Montenegro.[60] The final agreement was signed in Podgorica by both the Ottomans and Malisors during August 1912 and the highlanders had managed to thwart the centralist tendencies of the Young Turk government in relation to their interests.[60]

Independent Albania[]

The last tribal system of Europe located in northern Albania stayed intact until 1944 when Albanian communists seized power and ruled the country for half a century.[3] During that time the tribal system was weakened and eradicated by the communists.[3] After the collapse of communism in the early 1990s, northern Albania underwent demographic changes in areas associated with the tribes becoming in many instances depopulated.[62] Much of the population seeking a better life has moved either abroad or to Albanian cities such as Tiranë, Durrës or Shkodër and populations historically stemming from the tribes have become scattered.[62] Locals that remained in northern Albanian areas associated with the tribes have maintained an awareness of their tribal identity.[62]

List of historical tribes and tribal regions[]

This section includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2020) |

The following is a list of historical Albanian tribes and tribal regions. Some of the tribes are considered extinct because no collective memory of descent has survived (i.e Mataruga, Rogami etc) while others became slavicised very early on and the majority of the descendants no longer consider themselves Albanian (i.e Kuči, Mahine etc).

Malësia e Madhe[]

Malësia e Madhe, in the Northern Albanian Alps between Albania and Montenegro, historically has been the land of ten bigger and three smaller tribal regions.[63] Two of them, Suma and Tuzi, came together to form Gruda in the 15th-to-16th century. The people of this area are commonly called "highlanders" (Albanian: malësorë).

Brda-Zeta[]

Albania Veneta[]

Herzegovina - Ragusan hinterland[]

Dukagjin highlands[]

The Dukagjin highlands includes the following tribes:[70]

Gjakova highlands[]

There are six tribes of the Gjakova highlands (Albanian: Malësia e Gjakovës) also known as Malësia e Vogël (Lesser Malësia):[77]

- Nikaj[78] (commonly grouped as Nikaj-Mërtur)

- Mërturi[79] (commonly grouped as Nikaj-Mërtur)

- Krasniqi[80]

- Gashi[81]

- Bytyqi[82]

- Morina

Puka[]

The "seven tribes of Puka" (Albanian: shtatë bajrakët e Pukës), inhabit the Puka region.[83] Durham said of them: "Puka group ... sometimes reckoned a large tribe of seven bairaks. Sometimes as a group of tribes".[84]

Mirdita[]

Zadrimë - Lezha Highlands[]

- Bushati

- Bulgëri

- Kryezezi

- Manatia

- Vela

Mati - Kruja Highlands[]

- Kurbini

- Ranza

- Benda

- Bushkashi

- Doçi

- Kadiu

- Gjonima

- Progani

Upper Drin basin[]

Myzeqe[]

- Lalë

- Muzaka

Epirus[]

- Bua

- Malakasioi

- Zenebishi

- Spata

- Losha

- Kurveleshi

Historical[]

|

See also[]

Sources[]

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Galaty 2002, pp. 109–121.

- ^ Villar 1996, p. 316.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Elsie 2015, p. 1.

- ^ De Rapper 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Galaty 2011, p. 118.

- ^ Backer 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Galaty 2011, p. 89.

- ^ Backer 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gawrych 2006, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Durham 1928b, p. 63.

- ^ Durham 1928, p. 22.

- ^ Jelavich 1983, p. 81.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Galaty 2011, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gawrych 2006, pp. 30, 34, 119.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gawrych 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Jump up to: a b De Rapper 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kaser 2012, p. 298.

- ^ Galaty 2018, p. 145.

- ^ De Rapper 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Valentini 1956, p. 93.

- ^ Valentini 1956, p. 142.

- ^ Murawska-Muthesius, Katarzyna (2021). "Mountains and Palikars". Imaging and Mapping Eastern Europe: Sarmatia Europea to Post-Communist Bloc. Routledge. ISBN 9781351034401.

- ^ Valentini 1956, pp. 102, 103.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Elezi, Ismet (2006). "Zhvillimi historik i Kanunit të Labërisë". Kanuni i Labërisë (in Albanian). Tirana: Botimet Toena.

- ^ Mangalakova 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Hammond, N. G. L. Nutt, D. (ed.). "The Geography of Epirus". The Classical Review. Cambridge University Press. 8 (1): 72–74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mangalakova 2004, pp. 7, 8.

- ^ Desnickaja 1973, p. 48.

- ^ Galaty 2011, pp. 119–120:... northern Albanians' belief about their own history, based on notions of isolationism and resistance

- ^ Galaty 2011, pp. 119–120:... "negotiated peripherality"... the idea that people living in peripheral regions exploit their... position in important, often profitable ways... The implications and challenges of their national program.... in the Albanian Alps .. are very different from those that obtain in the south

- ^ Galaty 2011, pp. 119–120: "Most scholars of frontier life ...to be zones of active cultural creation. .. individuals and groups are in unique position to actively create and manipulate regional and national histories to their own advantage, ..."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gawrych 2006, p. 121.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29–30, 113.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gawrych 2006, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Balkanika. Srpska Akademija Nauka i Umetnosti, Balkanolos̆ki Institut. 2004. p. 252. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

...новчана глоба и изгон из племена (у северној Албанији редовно је паљена кућа изгоњеном члану племена). У Албанији се најсрамотнијом казном сматрало одузимање оружја.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Gawrych 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 1, 9.

- ^ Martucci 2017, p. 82.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 119.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gawrych 2006, p. 120.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Gawrych 2006, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 40.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 62.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29, 120, 138.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29, 118–121, 138, 209.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gawrych 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 159.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Gawrych 2006, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Elsie 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 15–98.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 15–35.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 36–46.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 47–57.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 68–78.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 81–88.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 58–66.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 115–148.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 115–127.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 128–131.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 132–137.

- ^ Elsie 2015, p. 138.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 138–142.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 143–148.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 149–174.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 149–156.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 160–165.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 166–169.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 170–174.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 175–196.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Durham 1928, p. 27.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 183–185.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 186–192.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 193–196.

- ^ Elsie 2015, p. 223.

Bibliography[]

- Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8557-0.

- Backer, Berit (2002). Behind Stone Walls: Changing household organisation among the Albanians of Kosovo (PDF). Dukagjini Balkan Books. ISBN 1508747946. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Bardhoshi, Nebi (2011). Gurtë e kufinit (PDF). UET Press. ISBN 978-99956-39-22-8.

- De Rapper, Gilles (2012). "Blood and Seed, Trunk and Hearth: Kinship and Common Origin in southern Albania". In Hemming, Andreas; Kera, Gentiana; Pandelejmoni, Enriketa (eds.). Albania: Family, Society and Culture in the 20th century. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 79–95. ISBN 9783643501448.

- Desnickaja, A. V. (1973). "Language Interferences and Historical Dialectology". Linguistics. 11 (113): 41–52. doi:10.1515/ling.1973.11.113.41.

- Durham, Edith (1928a). High Albania. LO Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-7035-2.

- Durham, Edith (1928b). Some tribal origins, laws and customs of the Balkans.

- Elsie, Robert (2003). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7380-3.

- Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857739322.

- Enke, Ferdinand (1955). Zeitschrift für vergleichende Rechtswissenschaft: einschliesslich der ethnologischen Rechtsforschung (in German). 58. Germany: Akademie für Deutsches Recht.

- Galaty, Michael L. (2002). "Modeling the Formation and Evolution of an Illyrian Tribal System: Ethnographic and Archaeological Analogs". In William A. Parkinson (ed.). The Archaeology of Tribal Societies. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1789201713.

- Galaty, Michael L. (2011). "Blood of Our Ancestors". In Helaine Silverman (ed.). Contested Cultural Heritage: Religion, Nationalism, Erasure, and Exclusion in a Global World. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-7305-4. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Galaty, Michael L. (2018). Memory and Nation Building: From Ancient Times to the Islamic State. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780759122628.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27458-6. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Kaser, Karl (2012). "Pastoral Economy and Family in the Dinaric and Pindus Mountains". In Karl Kaser (ed.). Household and Family in the Balkans: Two Decades of Historical Family Research at University of Graz. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643504067.

- Mertus, Julie (1999). Kosovo: How Myths and Truths Started a War. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21865-9. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Mangalakova, Tanya (2004). "The Kanun in Present-Day Albania, Kosovo, and Montenegro". International Centre for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relations. Sofia.

- Martucci, Donato (2017). "Le consuetudini giuridiche albanesi tra oralità e scrittura". Palaver (in Italian). 6 (2): 73–106. doi:10.1285/i22804250v6i2p73. ISSN 2280-4250.

- Valentini, Giuseppe (1956). Il diritto delle comunità nella tradizione giuridica albanese; generalità. Vallecchi.

- Villar, Francisco (1996). Los indoeuropeos y los orígenes de Europa (in Spanish). Madrid: Gredos. ISBN 84-249-1787-1.

- Tribes of Albania

- Albanian ethnographic regions

- Lists of modern Indo-European tribes and clans