Bjelopavlići

Coordinates: 42°39′N 19°01′E / 42.650°N 19.017°E Bjelopavlići (Cyrillic: Бјелопавлићи; Albanian: Palabardhi[1]), pronounced [bjɛlɔ̌paːv̞lit͡ɕi]) is a historical tribe (pleme) and valley in the Brda region of Montenegro, around the city of Danilovgrad.

Geography[]

The Bjelopavlići valley (also known as the Zeta river valley) is a strip of fertile lowland stretching along the Zeta river, being wider in the river's lower end, down to the confluence with Morača river near Podgorica. The valley has historically been densely populated, as fertile lowlands are rare in mountainous Montenegro, and it provided a corridor for road and rail connection between the two biggest Montenegrin cities, Podgorica and Nikšić. The largest settlement in the plain is the town of Danilovgrad which got name by Prince (Knjaz) Danilo Petrović. Confusingly, the other significant plain in Montenegro, Zeta plain has been named after Zeta river, although Zeta river itself does not flow through it.

History[]

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

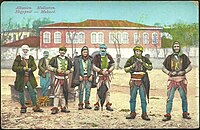

Originally an Albanian tribe, the Bjelopavlići underwent a process of gradual cultural integration into the neighbouring Slavic population.[2][3][4][5][6] Historically, the Bjelopavlići plain also hosted other Albanian tribes, such as the Malonšići.

In the Ottoman defter of the Sanjak of Scutari in 1485, Bjelopavlići appears as a distinct nahiya,with the total number of households in the 3 settlements of the nahiya were 159. These (with household numbers in brackets) were: Mariniqi (35), Dimitroviq (95), Ivrazha Grençi (29).[7]

The eponymous founder, Bijeli Pavle ("White Paul"), is said to have fled Metohija from the Ottomans, and settling in (Latin: Lusca, later known as Zeta). Bjelopavlići are first mentioned in a Ragusan document dating to 1411, when they, together with the Malonšići, Ozrinići and Maznići, had looted a ship of the Republic of Ragusa (from Dubrovnik). In 1496, the Ottomans conquered the greater part of Zeta and the surrounding area called "Hills" (Brda), which included[when?] the Vasojevići, Bjelopavlići, Piperi, Kuči, Bratonožići, Moračani and Rovčani.[citation needed] The tribe came under the Sanjak of Scutari.

The burning of Saint Sava's remains after the Banat Uprising provoked the Serbs in other regions to revolt against the Ottomans.[8] In 1596, an uprising broke out in the Bjelopavlići plain, then spread to Drobnjaci, Nikšić, Piva and Gacko (see Serb Uprising of 1596–97). It was suppressed due to lack of foreign support.[9]

In 1612 the Sultan sent the son of Mehmet Pasha to Podgorica to tackle the uprisings by the people. The Pasha remained in Podgorica for three months and then decided to ravage Bjelopavlići, taking 80 women and children as slaves, setting the village on fire and stealing animals. The males were hiding in other villages and upon the department of the Ottoman soldiers, the tribesmen attacked and killed 300 sipahis with their horses and baggage stolen.[10] In 1613, the Ottomans launched a campaign against the rebel tribes of Montenegro. In response, Bjelopavlići along with the tribes of Kuči, Piperi, Vasojevići, Kastrat, Kelmend, Shkrel and Hot formed a political and military union known as or “The Union of the Mountains” or “The Albanian Mountains”. In their shared assemblies, the leaders swore an oath of besa to resist with all their might any upcoming Ottoman expeditions, thereby protecting their self-government and disallowing the establishment of the authority of the Ottoman Spahis in the northern highlands ever again. Their uprising had a liberating character.[11] They reached an agreement with the rebels for 1,000 ducats and 12 slaves.[10] Venetian Mariano Bolizza (fl. May 1614) recorded that the region was under the command of the Ottoman army in Podgorica. There was 800 armed men of Bjelopavlići (Italian: Biellopaulichi), commanded by Neneca Latinović and Bratič Tomašević. Later that year, the Bjelopavlići, Kuči, Piperi, and Kelmend sent a letter to the kings of Spain and France claiming they were independent from Ottoman rule and did not pay tribute to the empire.[12] When the Pasha of Herzegovina attack city of Kotor 1657, the tribes of the Kelmendi and Bjelopavlići also participated in this battle[2]

In 1774, in the same month of the death of Šćepan Mali,[13] Mehmed Pasha Bushati attacked the Kuči and Bjelopavlići,[14] but was decisively defeated and returned to Scutari.[13]

Prince-Bishop Petar I (r. 1782-1830) waged a successful campaign against the bey of Bosnia in 1819; the repulse of an Ottoman invasion from Albania during the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29) led to the recognition of Montenegrin sovereignty over Piperi.[15] Petar I had managed to unite the Piperi and Bjelopavlići with Montenegro,[15] and when Bjelopavlići and the rest of the Hills (Seven hills) were joined into Peter's state, a polity officially called "Black Mountain (Montenegro) and the Hills".[16] A civil war broke out in 1847, in which the Piperi, Kuči, Bjelopavlići and Crmnica sought to confront the growing centralized power of new prince of Montenegro; the secessionists were subdued and their ringleaders shot.[17] Amid the Crimean War, there was a political problem in Montenegro; Danilo I's uncle, , urged for yet another war against the Ottomans, but the Austrians advised Danilo not to take arms.[18] A conspiracy was formed against Danilo, led by his uncles George and , the situation came to its height when the Ottomans stationed troops along the Herzegovinian frontier, provoking the mountaineers.[18] Some urged an attack on Bar, others raided into Herzegovina, and the discontent of Danilo's subjects grew so much that the Piperi, Kuči and Bjelopavlići, the recent and still unamalgamated acquisitions, proclaimed themselves an independent state in July, 1854.[18] In Danilo I's Code, dated to 1855, he explicitly states that he is the "knjaz (duke, prince) and gospodar (lord) of the Free Black Mountain (Montenegro) and the Hills".[19] Danilo was forced to take measurement against the rebels in Brda, some rebels crossed into Ottoman territory and some submitted and were to pay for the civil war they had caused.[18] Knjaz Danilo was assassinated in August, 1860 as he was boarding a ship at the port of Kotor. The assassin, Chief Todor Kadić of the Bjelopavlići, was said to be assisted by Austrian authorities in carrying out the assassination. Some speculate that there was a personal feud between the two, the fact that Danilo had an affair with Todor's wife and the ongoing mistreatment of the Bjelopavlići tribe by Danilo's guards and his forces.[20]

During Nikola I, the Bjelopavlici had bad relations with the rule as a member of the tribe, Andrija Radović, was sentenced to 15 years in a bombing trial and the trials in 1908-1909 further damaged relations.[21]

As an Old Montenegro tribe, the Bjelopavlici support an independent Montenegro.[22]

Families and notable people[]

This section does not cite any sources. (March 2020) |

All families have the slava of Parascheva of the Balkans (sv. Petka).

- Brotherhoods

- Vražegrmci and Martinići, descend from Buba Šćepanović

- Pavkovići, descend from Pavko Mitrović

- Brajović, descend from Brajo Pavković

- Petrušinovići, descend from Petar Mitrović

- Matijaševići and Tomaševići, descend from Nikola Mitrović

- Kalezići, descend from Kaleta Mitrović

- Lužani, natives

Notable people born or with descent from Bjelopavlići include:

- Ilija Garašanin, Serbian statesman, Prime Minister, Defender of the Constitution, creator of the Načertanije.

- Veselin Đuranović, Yugoslav communist politician.

- Milutin Garašanin, Serbian politician who held the post of Prime Minister of Serbia.

- Dragan Jočić, former Minister of Internal Affairs of Serbia.

- Jovica Stanišić, head of the State Security Service (SDB) within the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Serbia.

- Andrija Radović, politician and statesmen.

- Blagoje Jovović, member of the Partisan and later the Chetnik movement.

- Vasos Mavrovouniotis, Montenegrin general in the Greek revolution.

- Milutin Savić, Serbian revolutionary.

- Bajo Stanišić, officer of the Royal Yugoslav Army.

- Zorica Pavićević, Yugoslav handball player, competed in the 1984 Summer Olympics.

- Vojislav Brajović, Serbian actor.

- Zoran Kalezić, Montenegrin singer.

- Borislav Jovavonić, writer, poet and literary critic. .

References[]

- ^ Kola, Azeta (2017). "FROM SERENISSIMA'S CENTRALIZATION TO THE SELFREGULATING KANUN: THE STRENGTHENING OF BLOOD TIES AND THE RISE OF GREAT TRIBES IN NORTHERN ALBANIA FROM 15TH TO 17TH CENTURY". Acta Histriae: 369. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Tea Perinčić Mayhew, 2008 Dalmatia Between Ottoman and Venetian Rule: Contado Di Zara, 1645-1718 https://www.academia.edu/860183/Dalmatia_Between_Ottoman_and_Venetian_Rule_Contado_Di_Zara_1645-1718 #page=45

- ^ Robert Elsie, 2015, The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture, https://books.google.hr/books/about/The_Tribes_of_Albania.html?id=-EzWCQAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y #page=3

- ^ Mulić, Jusuf (2005). "O nekim posebnostima vezanim za postupak prihataanja Islama u Bosni i netačnostima koje mu se pripisuju." Anali Gazi Husrev-begove biblioteke. 23-24: 184. "U popisima, Arbanasi su iskazivani zajedno s Vlasima. To otežava uvid u moguće razlike kod prihvatanja islama od strane Vlaha i Arbanasa. Jedino se kod plemena za koja se izrijekom zna da su arbanaška, mogla utvrditi pojavnost u prihvatanju islama (Bjelopavlići, Burmazi, Grude, Hoti, Klimente/Koeljmend, Kuči, Macure, Maine, Malonšići/Malonze, Mataruge/Mataronge i Škrijelji). [In the lists, Albanians are reported together with Vlachs. This makes studying the possible differences in the acceptance of Islam by Vlachs and Albanians. Only with the tribes that are specifically known to be Albanian, could establish the occurrence of the acceptance of Islam (Bjelopavlići, Burmazi, Grude, Hoti, Klimenta / Koeljmend, Maine, Macura, Maine, Malonšići/Malonzo, Mataruge/Mataronge and Škrijelj).]"

- ^ Berishaj, Anton Kole (1995). Islamization -- Seed of Discord or the Only Way of Salvation for Albanians?. George Fox University. p. 7.

- ^ Kola, Azeta (2017). "FROM SERENISSIMA'S CENTRALIZATION TO THE SELFREGULATING KANUN: THE STRENGTHENING OF BLOOD TIES AND THE RISE OF GREAT TRIBES IN NORTHERN ALBANIA FROM 15TH TO 17TH CENTURY". Acta Histriae: 368-9. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Pulaha, Selami (1974). Defter i Sanxhakut të Shkodrës 1485. Academy of Sciences of Albania. pp. 119–122.

- ^ Bataković 1996, p. 33.

- ^ Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. "Преокрет у држању Срба". Историја српског народа (in Serbian). Belgrade: Јанус.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mariano Bolizza

- ^ Kola, Azeta (2017). "FROM SERENISSIMA'S CENTRALIZATION TO THE SELFREGULATING KANUN: THE STRENGTHENING OF BLOOD TIES AND THE RISE OF GREAT TRIBES IN NORTHERN ALBANIA FROM 15TH TO 17TH CENTURY". Acta Histriae: 368-9. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Kulišić, Špiro (1980). O etnogenezi Crnogoraca (in Montenegrin). Pobjeda. p. 41. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zapisi. Cetinjsko istorijsko društvo. 1939.

Истога мјесеца кад је Шћепан погинуо удари на Куче везир скадарски Мехмед - паша Бушатлија , но с великом погибијом би сузбијен и врати се у Скадар .

- ^ Летопис Матице српске. У Српској народној задружној штампарији. 1898.

Године 1774. везир скадарски Мехмед паша Бушатлија ударио је на Куче и Бјелопавлиће, који позваше у помоћ Црногорце те произиђе због овога међу Црном Гором и Арбанијом велики бој и Арбанаси су се повукли ...

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miller, p. 142

- ^ Etnografski institut (Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti) (1952). Posebna izdanja, Volumes 4-8. Naučno delo. p. 101.

Када, за владе Петра I, црногорсксу држави приступе Б^елопавлиЬи, па после и остала Брда, онда je, званично, „Црна Гора и Брда"

- ^ Miller, p. 144

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Miller, p. 218

- ^ Stvaranje, 7–12. Obod. 1984. p. 1422.

Црне Горе и Брда историјска стварност коЈа се не може занема- рити, што се види из назива Законика Данила I, донесеног 1855. године који гласи: „ЗАКОНИК ДАНИЛА I КЊАЗА И ГОСПОДАРА СЛОБОДНЕ ЦРНЕ ГОРЕ И БРДА".

- ^ Srdja Pavlovic (2008). Balkan Anschluss: The Annexation of Montenegro and the Creation of the Common South Slavic State. Purdue University Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-55753-465-1.

- ^ Ivo Banac (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1.[page needed]

- ^ Srdja Pavlovic (2008). Balkan Anschluss: The Annexation of Montenegro and the Creation of the Common South Slavic State. Purdue University Press. p. 143.

Sources[]

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1996). The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics. Dialogue Association.

- William Miller (12 October 2012). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors 1801-1927. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-26046-9.

- Bjelopavlići

- Landforms of Montenegro

- Valleys of Europe

- Tribes of Montenegro

- Danilovgrad Municipality