Western Schism

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

This article includes inline citations, but they are not properly formatted. (March 2021) |

A 14th-century miniature symbolizing the schism | |

| Date | 1378–1417 |

|---|---|

| Location | Europe |

| Type | Christian Schism |

| Cause |

|

| Motive | International rivalries in Catholic Europe |

| Outcome | Reunification of Catholic Church in 1415–1429 |

The Western Schism, also called Papal Schism, The Vatican Standoff, Great Occidental Schism and Schism of 1378 (Latin: Magnum schisma occidentale, Ecclesiae occidentalis schisma), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417[1] in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon both claimed to be the true pope, joined by a third line of Pisan popes in 1409. The schism was driven by personalities and political allegiances, with the Avignon papacy being closely associated with the French monarchy. These rival claims to the papal throne damaged the prestige of the office.[2]

The papacy had resided in Avignon since 1309, but Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377. However, the Catholic Church split in 1378 when the College of Cardinals elected both Urban VI and Clement VII pope within six months of Gregory XI's death. After several attempts at reconciliation, the Council of Pisa (1409) declared that both popes were illegitimate and elected a third pope. The schism was finally resolved when the Pisan pope John XXIII called the Council of Constance (1414–1418). The Council arranged the abdication of both the Roman pope Gregory XII and the Pisan pope John XXIII, excommunicated the Avignon pope Benedict XIII, and elected Martin V as the new pope reigning from Rome.

The affair is sometimes referred to as the Great Schism, although this term is also used for the East–West Schism of 1054 between the Churches remaining in communion with the See of Rome and the Eastern Orthodox Churches.

Timeline[]

|

Recognition[]

| Papacy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporters |

|

|

History[]

Origin[]

Since 1309, the papacy had resided in Avignon, a papal enclave surrounded by France. The Avignon Papacy had developed a reputation for corruption that estranged major parts of Western Christendom. This reputation can be attributed to perceptions of predominant French influence, and to the papal curia's efforts to extend its powers of patronage and increase its revenues.[citation needed] The last undisputed Avignon pope, Gregory XI, decided to return to Rome on 17 January 1377.[3] However, Pope Gregory XI announced his intention to return to Avignon just after the Easter celebrations of 1378.[4] This was at the entreaty of his relatives, his friends, and nearly everyone in his retinue.

Before he could leave, Gregory XI died in the Vatican palace on 27 March 1378.[5] The Romans put into operation a plan to use intimidation and violence (impressio et metus) to ensure the election of a Roman pope. The pope and his Curia were back in Rome after seventy years in Avignon, and the Romans were prepared to do everything in their power to keep them there.[6] On 8 April 1378, the cardinals elected Bartolomeo Prignano, the archbishop of Bari, as Pope Urban VI. Urban had been a respected administrator in the papal chancery at Avignon, but as pope he proved suspicious, reformist, and prone to violent outbursts of temper.[7]

Two popes[]

Most of the cardinals who had elected Urban VI soon regretted their decision and removed themselves to Anagni. Meeting at Fondi, the College of Cardinals elected Robert of Geneva as Pope Clement VII on 20 September 1378. The cardinals argued that the election of Urban VI was invalid because it had been done for fear of the rioting Roman crowds.[8][9][10] Unable to maintain himself in Italy, Clement VII reestablished a papal court in Avignon.[11] Clement had the immediate support of Queen Joanna I of Naples and of several of the Italian barons. Charles V of France, who seems to have been sounded out beforehand on the choice of the Roman pontiff, soon became his warmest protector. Clement eventually succeeded in winning to his cause Castile, Aragon, Navarre, a great part of the Latin East, Flanders, and Scotland.[12]

The pair of elections threw the Church into turmoil. There had been antipope claimants to the papacy before, but most of them had been appointed by various rival factions. In this case, the College of Cardinals had elected both the pope and the antipope.[13] The conflicts quickly escalated from a church problem to a diplomatic crisis that divided Europe. Secular leaders had to decide which claimant they would recognize.

In the Iberian Peninsula there were the Fernandine Wars (Guerras fernandinas) and the 1383–1385 Crisis in Portugal, during which dynastic opponents supported rival claimants to the papal office. Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion in Wales recognized the Avignon pope, while England recognized the Roman pope.

Consequences[]

Sustained by such national and factional rivalries throughout Catholic Christianity, the schism continued after the deaths of both Urban VI in 1389 and Clement VII in 1394. Boniface IX, who was crowned at Rome in 1389, and Benedict XIII, who reigned in Avignon from 1394, maintained their rival courts. When Pope Boniface died in 1404, the eight cardinals of the Roman conclave offered to refrain from electing a new pope if Benedict would resign; but when Benedict's legates refused on his behalf, the Roman party then proceeded to elect Pope Innocent VII.

In the intense partisanship characteristic of the Middle Ages, the schism engendered a fanatical hatred noted by Johan Huizinga:[14] when the town of Bruges went over to the "obedience" of Avignon, a great number of people left to follow their trade in a city of Urbanist allegiance; in the 1382 Battle of Roosebeke, the oriflamme, which might only be unfurled in a holy cause, was taken up against the Flemings, because they were Urbanists and thus viewed by the French as schismatics.[citation needed]

Efforts were made to end the Schism through force or diplomacy. The French crown even tried to coerce Benedict XIII, whom it supported, into resigning. None of these remedies worked. The suggestion that a church council should resolve the Schism, first made in 1378, was not adopted at first, because canon law required that a pope call a council.[citation needed] Eventually theologians like Pierre d'Ailly and Jean Gerson, as well as canon lawyers like Francesco Zabarella, adopted arguments that equity permitted the Church to act for its own welfare in defiance of the letter of the law.

Three popes[]

Eventually the cardinals of both factions secured an agreement that the Roman pope Gregory XII and the Avignon pope Benedict XIII would meet at Savona. They balked at the last moment, and both groups of cardinals abandoned their preferred leaders. The Council of Pisa met in 1409 under the auspices of the cardinals to try solving the dispute. At the fifteenth session, 5 June 1409, the Council of Pisa attempted to depose both the Roman and Avignon popes as schismatical, heretical, perjured and scandalous,[15] but it then added to the problem by electing a third pope, Alexander V. He reigned briefly in Pisa from June 26, 1409, to his death in 1410, when he was succeeded by John XXIII, who won some but not universal support.

Resolution[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2015) |

Finally, the Council of Constance was convened by the Pisan pope John XXIII in 1414 to resolve the issue. The council was also endorsed by the Roman pope Gregory XII, giving it greater legitimacy. The council, advised by the theologian Jean Gerson, secured the resignations of both Gregory XII and John XXIII, while excommunicating the Avignon pope Benedict XIII, who refused to step down. After a prolonged sede vacante, the Council elected Pope Martin V in 1417, essentially ending the schism.

Nonetheless, the Crown of Aragon did not recognize Pope Martin V and continued to recognize Benedict XIII. Archbishops loyal to Benedict XIII subsequently elected Antipope Benedict XIV (Bernard Garnier) and three followers simultaneously elected Antipope Clement VIII, but the Western Schism was by then practically over. Clement VIII resigned in 1429 and apparently recognized Martin V.

Gregory XII's abdication in 1415 was the last papal resignation until Benedict XVI in 2013.

Aftermath[]

After its resolution, the Western Schism still affected the Catholic Church for years to come. One of the most significant of these involved the emergence of the theory called conciliarism, founded on the success of the Council of Constance, which effectively ended the conflict. This new reform movement held that a general council is superior to the pope on the strength of its capability to settle things even in the early church such as the case in 681 when Pope Honorius was condemned by a council called Constantinople III.[16] There are theorists such as John Gerson who explained that the priests and the church itself are the sources of the papal power and, thus, the church should be able to correct, punish, and, if necessary, depose a pope.[17] For years, the so-called conciliarists have challenged the authority of the pope and they became more relevant after a convened council also known as the Council of Florence (1439–1445) became instrumental in achieving ecclesial union between the Catholic Church and the churches of the East.[18]

Pope Pius II (r. 1458–1464) settled the issue by decreeing that no appeal could be made from pope to council. Thus, a papal election could not be overturned by anyone but the elected pope himself. No such crisis has arisen since the 15th century, and so there has been no need to revisit this decision.

There was also a marked decline in morality and discipline within the church. Scholars note that although the Western Schism did not directly cause such a phenomenon, it was a gradual development rooted in the conflict, effectively eroding the church authority and its capacity to proclaim the gospel.[19] This was further aggravated by the dissension caused by the Protestant Reformation, which created a lot of unrest.

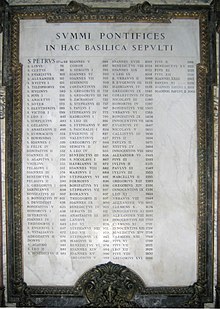

Official list of popes[]

For the next five centuries, the Catholic Church recognized the Roman popes as the legitimate line from 1378 to 1409, followed by the Pisan popes from 1409 to 1415. All Avignon popes after 1378 are considered to be antipopes. This recognition is reflected in the numbering of popes Alexander VI, VII, and VIII, who numbered themselves consecutively after their Pisan namesake Alexander V.

The recognition of the Pisan popes made the continued legitimacy of the Roman pope Gregory XII doubtful for 1409–1415. The Annuario Pontificio for 1860 listed the Pisan popes as true popes from 1409 to 1415, but it acknowledged that Gregory XII's reign ended in either 1409 or 1415.[20] The Annuario Pontificio for 1864 eliminated the overlapping period by ending Gregory XII's reign in 1409, listing the last three popes of the schism as Gregory XII (1406–1409), Alexander V (1409–1410), and John XXIII (1410–1415).[21] This remained the official chronology of popes through the mid-20th century.[22]

The Western Schism was reinterpreted in 1958 when Pope John XXIII chose to reuse the ordinal XXIII, citing "twenty-two [sic] Johns of indisputable legitimacy."[23] (There had actually been nineteen undisputed Johns due to antipopes and numbering errors.) The Pisan popes Alexander V and John XXIII are now considered to be antipopes. This reinterpretation is reflected in modern editions of the Annuario Pontificio, which extend Gregory XII's reign to 1415. The line of Roman popes is now retroactively recognized by the Catholic Church as the sole legitimate line during the Western Schism. However, Popes Alexander VI through VIII have not been renumbered, leaving a gap in the numbering sequence.

According to Broderick (1987):

Doubt still shrouds the validity of the three rival lines of pontiffs during the four decades subsequent to the still disputed papal election of 1378. This makes suspect the credentials of the cardinals created by the Roman, Avignon, and Pisan claimants to the Apostolic See. Unity was finally restored without a definitive solution to the question; for the Council of Constance succeeded in terminating the Western Schism, not by declaring which of the three claimants was the rightful one, but by eliminating all of them by forcing their abdication or deposition, and then setting up a novel arrangement for choosing a new pope acceptable to all sides. To this day the Church has never made any official, authoritative pronouncement about the papal lines of succession for this confusing period; nor has Martin V or any of his successors. Modern scholars are not agreed in their solutions, although they tend to favor the Roman line.[24]

Notes[]

- ^ "Western Schism". britannica.com. December 2014.

- ^ Johannes Fried (2015), "Chapter 7: The Long Century of Papal Schisms", in: The Great Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 167–237.

- ^ J.N.D. Kelly, Oxford Dictionary of the Popes, p. 227.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius (1906), Annie Hamilton (ed.), History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages Vol. VI, Part II (London: George Bell 1906), p. 490-491.

- ^ Conradus Eubel (ed.) (1913). Hierarchia catholica (in Latin). Tomus 1 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. p. 21.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) (in Latin)

- ^ Mandell Creighton (1882). The great schism. The Council of Constance, 1378–1418. Houghton, Mifflin & Company. pp. 49–68.

- ^ Cardinal Hugues de Montelais stated that he had a mental reservation against Bartolomeo Prignano, on the grounds that he was "unsuitable", due to his temperament and temper: "dixit in vera conscientia sua quod ante ingressum conclavis nec post nunquam habuit in mente consentiendi in eum nec eligendi eum, nec etiam cum esset in conclave nominavit eum, quia agnoscebat eum quod esset melancholicus et furiosus homo." Stephanus Baluzius [Étienne Baluze], Vitae Paparum Avinionensium Volume 1 (Paris: apud Franciscum Muguet 1693) column 1270.

- ^ T. Wilson-Smith, Joan of Arc, p. 24

- ^ Seeking Legitimacy:Art and Manuscripts for the Popes in Avignon from 1378 to 1417, Cathleen A. Fleck

- ^ A Companion to the Great Western Schism (1378–1417), ed. Joëlle Rollo-Koster, Thomas M. Izbicki, (Brill, 2009), 241.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Weber, Nicholas Aloysius (1912). "Robert of Geneva". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Weber, Nicholas Aloysius (1912). "Robert of Geneva". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Walsh, Michael J. and Walsh, Michael. The Cardinals: Thirteen Centuries of the Men Behind the Papal Throne, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2011, p. 157ISBN 9780802829412

- ^ Johannes Fried (2015) pp. 167–237. The Long Century of Papal Schisms. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages, 1924:14

- ^ J. P. Adams, Council of Pisa: Deposition of Benedict XIII and Gregory XII, with additional references. Retrieved 02/26/2106.

- ^ Bausch, William; Cannon, Carol Ann; Obach, Robert (1989). Pilgrim Church: A Popular History of Catholic Christianity. Mystic, CT: Twenty-Third Publications. p. 211. ISBN 0896223957.

- ^ Bausch, Cannon, & Oback, p. 211.

- ^ O'Connor, James Thomas (2005). The Hidden Manna: A Theology of the Eucharist. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 204. ISBN 1586170767.

- ^ Coriden, James (2004). An Introduction to Canon Law. New York: Paulist Press. p. 21. ISBN 0809142562.

- ^ Annuario pontificio per l'anno 1960. Rome. 1860. pp. 21–22.

206. Gregorio XII, Corario, Veneto, fu creato nel 1406. Il suo Pontificato, giusta il sentimento di quei che lo credono terminato nella Sess. 15. del Concilio di Pisa, durò anni 2, mesi 7 e giorni 4, e secondo l'opinione di coloro che lo prolungano fino alla Sess. 14 del Concilio di Constanza, nella quale Gregorio solennemente rinunziò, durò anni 8, mesi 7 e giorni 4.

207. Alessandro V, Filargo, di Candia, fu creato nel 1409. Il suo Pontificato durò mesi 10 e giorni 8.

208. Giovanni XXIII, Cossa, Napolitano, fu creato nel 1410. Il suo Pontificato durò anni 5 e giorni 13. - ^ Annuario pontificio per l'anno 1864. Rome. 1864. p. 34.

CCV. Gregorio XII, Veneto, Corario, c. 1406, rinunziò 1409, G. a. 2, m. 6, g. 4.

CCVI. Allesandro V, di Candia, Filargo, c. 1409, m. 1410, G. m. 10, g. 8.

CCVII. Giovanni XXII, o XXIII, o XXIV, Napoletano, Cossa, c. 1410, G. a. 5, g. 13. - ^ Annuario pontificio per l'anno 1942. Rome. 1942. p. 21.

205. Gregorio XII, Veneto, Correr (c. 1406, cessò a. 1409, m. 1417) - Pont. a. 2, m. 6. g. 4. 206. Alessandro V, dell'Isola di Candia, Filargo (c. 1409, m. 1410). - Pont. m. 10, g. 8. 207. Giovanni XXII o XXIII o XXIV, Napoletano, Cossa (c. 1410, cessò dal pontificare 29 mag. 1415

- ^ "I Choose John ..." Time. 10 November 1958. p. 91.

- ^ Broderick, J.F. 1987. "The Sacred College of Cardinals: Size and Geographical Composition (1099–1986)." Archivum historiae Pontificiae, 25: p. 14.

Bibliography[]

- Gail, Marzieh (1969). The Three Popes: An Account of the Great Schism. New York, 1969.

- Gayet, Louis (1889). Le grand schisme d'Occident. 2 volumes. Paris-Florence-Berlin: Loescher et Seeber 1889. (in French)

- Prerovsky, Ulderico (1960). L' elezione di Urbano VI, e l' insorgere dello scisma d' occidente. Roma: Società alla Biblioteca Vallicelliana 1960. (in Italian)

- Rollo-Koster, Joëlle and Izbicki, Thomas M. (editors) (2009). A Companion to the Great Western Schism (1378–1417) Leiden: Brill, 2009.

- Smith, John Holland (1970). The Great Schism: 1378. New York 1970.

- Ullman, Walter (1948). The Origins of the Great Schism: A study in fourteenth century ecclesiastical history. Hamden, Conn: Archon Books, 1967 (reprint of 1948 original publication)) [strongly partisan for Urban VI].

- Valois, Noël (1890). "L' élection d'Urbain VI. et les origines du Grand Schisme d'Occident," in: Revue des questions historiques 48 (1890), pp. 353–420. (in French)

- Valois, Noël (1896). La France et le Grand Schisme d'Occident. Tome premier. Paris: Alphonse Picard 1896.

External links[]

- Western Schism

- 1370s in Europe

- 1378 in Europe

- 1380s in Europe

- 1390s in Europe

- 1400s in Europe

- 1410s in Europe

- 1417 in Europe

- 14th-century Catholicism

- 15th-century Catholicism

- Avignon Papacy

- Christian terminology

- History of the papacy

- 1370s in Christianity

- 1380s in Christianity

- 1390s in Christianity

- 1400s in Christianity

- 1410s in Christianity