Franjo Tuđman

Vrhovnik Franjo Tuđman | |

|---|---|

Tuđman in 1995 | |

| President of Croatia | |

| In office 22 December 1990 – 10 December 1999 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Himself (as President of the Presidency of the Republic of Croatia) |

| Succeeded by |

|

| President of the Presidency of the Republic of Croatia | |

| In office 25 July 1990 – 22 December 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Deputy | Josip Manolić |

| Preceded by | Himself (as President of the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Croatia) |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as President of Croatia) |

| President of the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Croatia | |

| In office 30 May 1990 – 25 July 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Stjepan Mesić (as President of the Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Croatia) |

| Deputy | Josip Manolić |

| Preceded by | Ivo Latin |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as President of the Presidency of the Republic of Croatia) |

| President of the Croatian Democratic Union | |

| In office 17 June 1989 – 10 December 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 May 1922 Veliko Trgovišće, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes |

| Died | 10 December 1999 (aged 77) Zagreb, Croatia |

| Resting place | Zagreb, Croatia |

| Nationality | Croatian |

| Political party | SKH (1942–1967) HDZ (1989–1999) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Profession | Politician, historian, soldier |

| Signature | |

| Website | tudjman |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | "Francek" |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Yugoslav Partisans (1942–45) Yugoslav People's Army (1945–61) Republic of Croatia Armed Forces (1995–99) |

| Years of service | 1942–1961 1995–1999 |

| Rank | Major general (YPA) Vrhovnik (HV)[1][2] |

| Unit | 10th Zagreb Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II in Yugoslavia Croatian War of Independence Bosnian War |

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of Croatia

Elections Family

|

||

Franjo Tuđman, also written as Franjo Tudjman[3][4] (Croatian: [frǎːɲo tûdʑman] (![]() listen); 14 May 1922 – 10 December 1999), was a Croatian politician and historian. Following the country's independence from Yugoslavia he became the first President of Croatia and served as president from 1990 until his death in 1999. He was the 9th and last President of the Presidency of SR Croatia from May to July 1990.

listen); 14 May 1922 – 10 December 1999), was a Croatian politician and historian. Following the country's independence from Yugoslavia he became the first President of Croatia and served as president from 1990 until his death in 1999. He was the 9th and last President of the Presidency of SR Croatia from May to July 1990.

Tuđman was born in Veliko Trgovišće. In his youth he fought during World War II as a member of the Yugoslav Partisans. After the war he took a post in the Ministry of Defence, later attaining the rank of major general of the Yugoslav Army in 1960. After his military career he dedicated himself to the study of geopolitics. In 1963 he became a professor at the Zagreb Faculty of Political Sciences. He received a doctorate in history in 1965 and worked as a historian until coming into conflict with the regime. Tuđman participated in the Croatian Spring movement that called for reforms in the country and was imprisoned for his activities in 1972. He lived relatively anonymously in the following years until the end of communism, whereupon he began his political career by founding the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) in 1989.

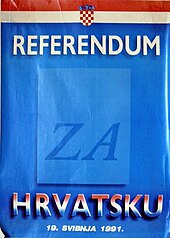

HDZ won the first Croatian parliamentary elections in 1990 and Tuđman became the President of the Presidency of SR Croatia. As president, Tuđman introduced a new constitution and pressed for the creation of an independent Croatia. On 19 May 1991, an independence referendum was held, which was approved by 93 percent of voters. Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991. Areas with a Serb majority revolted, backed by the Yugoslav Army, and Tuđman led Croatia during its War of Independence. A ceasefire was signed in 1992, but the war had spread into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Croats fought in an alliance with Bosniaks. Their cooperation fell apart in late 1992 and Tuđman's government sided with Herzeg-Bosnia during the Croat–Bosniak War with the goal to reunite the Croatian people, a move that brought criticism from the international community. In March 1994, he signed the Washington Agreement with Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović that re-allied Croats and Bosniaks. In August 1995, he authorized a major offensive known as Operation Storm which effectively ended the war in Croatia. In the same year, he was one of the signatories of the Dayton Agreement that put an end to the Bosnian War. He was re-elected president in 1992 and 1997 and remained in power until his death in 1999. While supporters point out his role in achieving Croatian independence, critics have described his presidency as authoritarian. Surveys after Tuđman's death have generally shown a high favorability rating among the Croatian public.

Early life and education

Franjo Tuđman was born on 14 May 1922 in Veliko Trgovišće, a village in the northern Croatian region of Hrvatsko Zagorje, at the time part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The family moved to the house marked as his birthplace soon after he was born.[5][6] His father Stjepan ran a local tavern and was a politically active member of the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS).[7] He had been president of the HSS committee in Veliko Trgovišće for 16 years (1925–1941 and had been elected as mayor of Veliko Trgovišće in 1936 and 1938).[8] Mato, Andraš and Juraj, brothers of Stjepan Tuđman, emigrated to the United States.[9] Another brother, Valentin, also tried to emigrate but a travelling accident prevented him and kept him in Veliko Trgovišće, where he worked as an (uneducated) veterinarian.[9]

Besides Franjo, Stjepan Tuđman had an elder daughter Danica Ana (who died as a baby), Ivica (born in 1924) and Stjepan "Štefek" (born in 1926).[9] When Franjo Tuđman was 7 his mother Justina (née Gmaz) died while bearing her fifth child.[10][11] Tuđman's mother was a devout Catholic, unlike his father and stepmother. His father, like Stjepan Radić, had anticlerical attitudes and young Franjo adopted his views.[7] As a child Franjo Tuđman served as an altar boy in the local parish.[12] Tuđman attended elementary school in his native village from 15 September 1929 to 30 June 1933 and was an excellent student.[13]

He attended secondary school for eight years, starting in the autumn 1935.[14] The reasons for the interruption are not clear, but it is assumed that the primary cause was an economic crisis in that period.[15] According to some sources the local parish helped young Franjo to continue his education[16] and his teacher even proposed him to be educated to become a priest.[17] When he was 15 his father brought him to Zagreb, where he met Vladko Maček, the president of the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS).[7] At first young Franjo liked the HSS, but later he turned towards communism.[18] On 5 November 1940 he was arrested during student demonstrations celebrating the anniversary of the Soviet October revolution.[19]

World War II

On 10 April 1941, when Slavko Kvaternik proclaimed the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) Tuđman left school and started publishing secret newspapers with his friend Vlado Stopar.[19] He was recruited into the Yugoslav partisans at the beginning of 1942 by Marko Belinić.[19] His father also joined the partisans and became a founder of ZAVNOH. According to Tuđman, his father was arrested by the Ustaše, and one of his brothers was taken to a concentration camp.[19] They both managed to survive, unlike the youngest brother Stjepan[19] who was killed by the Gestapo[20] fighting for the Partisans in 1943.

Tuđman was traveling between Zagreb and Zagorje using false documents which identified him as a member of the Croatian Home Guard. There he was helping to activate a partisan division in Zagorje.[19] On 11 May 1942, while carrying Belinić's letter, he was arrested by the Ustaše, but managed to escape from the police station.[19]

Military career

Franjo Tuđman and Ankica Žumbar were married on 25 May 1945 at the Belgrade city council.[21] In this way they wanted to confirm their faith in the Communist movement and the importance of civil ritual over religious ones.[21] (In May 1945 the government created the law which allowed civil weddings, taking weddings (among other things) out of Church jurisdiction). They returned to work that same day.[21]

On 26 April 1946, his father Stjepan and stepmother were found dead.[21] Tuđman never clarified the circumstances of their death. According to the police, his father Stjepan killed his wife and then himself. Other theories accuse Ustaše guerrillas (Crusaders) and members of the Yugoslav secret police (OZNA).[21]

Franjo and Ankica did not qualify as secondary school graduates until after the war, in Belgrade.[22] He graduated from the Partisan High school in 1945 and she finished five semesters of English language in the Yugoslav Foreign Office.[22]

In 1953, Tuđman was promoted to the position of colonel and in 1959 he became a major general.[22] At the age of 38, he had become the youngest general in the Yugoslav army. His promotion was not extreme but it was atypical for a Croat because senior officers were increasingly likely to be Serbs and Montenegrins.[22] In 1962 Serbs and Montenegrins composed 70% of army generals.[23]

On 23 May 1954, he became secretary of JSD Partizan Belgrade[24] and in May 1958 its president,[24] becoming the first colonel to occupy that position (all previous holders were generals).[24] He was placed in that position in order to solve administration problems inside of the club, especially the football section. When he arrived, JSD Partizan Belgrade was a kind of intelligence battlefield where leaders of UDBA and KOS struggled for influence.[25] That caused clubs (despite having notable and good players) to have bad results, especially its football section.[26] During his club presidency the club adopted the black-white striped kit which is used to this day. According to Tuđman he wanted to create a club that would have a pan-Yugoslav image and oppose the Red Star that had an exclusive Serbian image.[27] Tuđman was inspired by FC Juventus uniforms. However, Stjepan Bobek (former player of FK Partizan) claimed that uniform colors idea was in fact his which he passed on to Tuđman.[28]

Tuđman attended the military academy in Belgrade, like many officers who did not have formal military education. He graduated from the tactical school on 18 July 1957 as an excellent student.[29] One of his teachers was Dušan Bilandžić, who would be a future advisor.[30] Before he turned 40 years old, he had risen to become the youngest general in the Yugoslav Army. He was prominent in attending to communist indoctrination while based in Belgrade, where his three children were born.[31]

Institute

In 1963, he became professor at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Political Sciences where he taught a course called "Socialist Revolution and Contemporary National History".[32] He left active army service in 1961 at his own request and began working at the Institut za historiju radničkoga pokreta Hrvatske (English: Institute for the History of Workers' Movement of Croatia), and remained its director until 1967.[32]

Tuđman's increasing insistence on a Croatian interpretation of history[clarification needed] turned many professors from University of Zagreb like Mirjana Gross and Ljubo Boban against him.[33] In April 1964 Boban denounced Tuđman as a "nationalist".[33] During Tuđman's leadership the Institute became a source of alternative interpretations of Yugoslav history which caused his conflict with official Yugoslav historiography.[30] He did not have an appropriate academic degree to qualify him as a historian. He began to realize that he would need to obtain a doctorate in order to keep his position. His dissertation was entitled "The causes of the crisis of the Yugoslav monarchy from unification in 1918 until its breakdown in 1941", and was a compilation of some of his previously published works. The University of Zagreb's Faculty of Philosophy rejected his dissertation, on the grounds that some parts of it had already been published.[34] The Faculty of Arts in Zadar (then part of University of Zagreb, today University of Zadar) accepted it and he graduated on 28 December 1965.[35][34]

In his thesis he stated that the primary cause of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia's breakdown was the repressive and corrupted regime which was at odds with the contemporary mainstream Yugoslav historiography which considered Croatian nationalism to be its primary cause.[34] Bogdanov and Milutinović (both ethnic Serbs) did not object to this. However, the Zagreb-based publisher Naprijed cancelled the contract following his refusal to change some "controversial" statements in the book.[34] He publicly supported the goals of Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language.[clarification needed] The Croatian Parliament and League of Communists of Croatia from Zagreb, however, attacked it and the board of the institute requested Tuđman's resignation.[36]

In December 1966, Ljubo Boban accused Tuđman of plagiarism,[37] stating that Tuđman had compiled four-fifths of his doctoral thesis, The Creation of the Socialist Yugoslavia, from Boban's work. Boban offered conclusive proofs to his claim from articles published previously in the magazine Forum and the rest from Boban's own thesis.[37] Tuđman was then expelled from the Institute and forced to retire in 1967.[38]

Between 1962 and 1967, he was the president of the "Main Committee for International Relations of the Croatian League of Communists Main Board"[clarification needed] and deputy in the Croatian parliament between 1965 and 1969.[38]

Dissident politics

Apart from his book on guerrilla warfare, Tuđman wrote a series of articles criticizing the Yugoslav Socialist establishment. His most important book from that period was Velike ideje i mali narodi ("Great ideas and small nations"), a monograph on political history that brought him into conflict with the central dogmas of the Yugoslav Communist elite with regard to the interconnectedness of the national and social elements in the Yugoslav revolutionary war (during World War II).

In 1970, he became a member of the Croatian Writers' Society. In 1972 he was sentenced to two years in prison for subversive activities during the Croatian Spring. According to Tuđman's own testimony[citation needed], the Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito personally intervened to recommend the court to be lenient in his case, sparing him a longer prison sentence. The authorities of SR Croatia additionally intended to prosecute Tuđman on charges of espionage, which carried a sentence of 15–20 years in prison with hard labour, but the charge was commuted by Tito. Other sources mention that Miroslav Krleža, a writer, lobbied on Tuđman's behalf.[32] According to Tuđman, he and Tito were close friends.[39] However, Tuđman later described Tito's crackdown as an "autocratic coup d'état".[40]

The Croatian Spring was a national movement set in motion by Tito and the Croatian communist party chairman Vladimir Bakarić amid the climate of growing liberalism in the late 1960s. It was initially a tepid and ideologically controlled party liberalism, but it soon grew into a mass nationalist-based manifestation of dissatisfaction with the position of Croatia within Yugoslavia. As a result, the movement was suppressed by Tito, who used the military and the police to put a stop to what he saw as separatism and a threat to the party's influence. Bakarić quickly distanced himself from the Croatian communist leadership that he himself had helped to gain power earlier and sided with the Yugoslav president. However, Tito took the protesters' demands into consideration and in 1974 the new Yugoslav constitution granted the majority of the demands sought by the Croatian Spring. On other topics like Communism and one-party political monopoly Tuđman remained mostly within the framework of the communist ideology of the day. His sentence was eventually commuted by Tito's government and Tuđman was released after spending nine months in prison.[citation needed]

In 1977, he traveled to Sweden using a forged Swedish passport to meet members of the Croatian diaspora.[41] His trip apparently went unnoticed by Yugoslav police. However, on that trip he gave an interview to Swedish TV about the position of Croats in Yugoslavia that was later broadcast.[41] Upon returning to Yugoslavia, Tuđman was put on trial again in 1981 because of this interview, and was accused for having spread "enemy propaganda". On 20 February 1981 he was found guilty and sentenced to three years of prison and 5 years in house arrest.[42] However, he served only eleven months of the sentence.[38] In June 1987, he became a member of the Croatian PEN centre.[38] On 6 June 1987, he travelled to Canada with his wife to meet Croatian Canadians.[43] They were trying not to discuss sensitive issues with emigrants abroad fearing that some might be agents of the Yugoslav secret police UDBA, which was a common practice at the time.[44]

During his trips to Canada he met many Croatian emigrants who were natives of Herzegovina or were of Herzegovinian ancestry. Some of these later became Croatian government officials after the country's independence, the most prominent of whom was Gojko Šušak, whose father and elder brother had been members of the Ustaše.[45] These meetings abroad in the late 1980s later gave rise to many conspiracy theories. According to these rumours the Croats of Herzegovina had somehow used the meetings to earn a huge amount of influence inside the HDZ, as well as the post-independence Croatian establishment.[46]

Formation of the national program

In the latter part of the 1980s, when Yugoslavia was nearing its demise, torn by conflicting national aspirations, Tuđman formulated a Croatian national programme that can be summarized in the following way:

- The primary goal is the establishment of the Croatian nation-state; therefore all ideological disputes from the past should be thrown away. In practice, this meant strong support from the anti-Communist Croatian diaspora, especially financial.

- Even though Tuđman's final goal was an independent Croatia, he was well aware of the realities of internal and foreign policy. His chief initial proposal was not a fully independent Croatia, but a confederate Yugoslavia with growing decentralization and democratization.

- Tuđman envisaged Croatia's future as a welfare capitalist state[clarification needed] that will inevitably move towards central Europe and away from the Balkans.

- With regard to the burning issues of national conflicts, his vision was the following (at least initially): he asserted that Serbian nationalism, controlled by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), could wreak havoc on Croatian and Bosnian soil. The JNA, according to some estimates the fourth European military force re firepower, was being rapidly Serbianized, both ideologically and ethnically,[47] in less than four years. Tuđman's proposal was that Serbs in Croatia, who made up 12% of Croatia's population, should gain cultural freedom with elements of territorial autonomy.[citation needed]

- As far as Bosnia and Herzegovina was concerned, Tuđman was more ambivalent: Tuđman did not take a separate Bosnia seriously as shown by his comments to a television crew "Bosnia was a creation of the Ottoman invasion ... Until then it was part of Croatia, or it was a kingdom of Bosnia, but a Catholic kingdom, linked to Croatia".[48]

On 17 June 1989, Tuđman founded the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). Essentially, this was a nationalist Croatian movement that affirmed Croatian values based on Catholicism blended with historical and cultural traditions which had been generally suppressed in communist Yugoslavia. The aim was to gain national independence and to establish a Croatian nation-state.[citation needed]

1990 election campaign

Internal tensions that had broken up the Communist party of Yugoslavia prompted the governments of federal Republics to schedule free multiparty elections in spring 1990. These were the first free multi-party elections for the Croatian Parliament since 1913. The HDZ held its first convention on 24–25 February 1990, when Tuđman was elected its president. The election campaign took place from late March until 20 April 1990. Tuđman recruited several supporters from members of the diaspora who returned home, most importantly Gojko Šušak.[49]

Tuđman based his campaign mostly on the national question. He stated that the dinar earned in Croatia should stay in Croatia, thus objecting the subsidies for less developed parts of Yugoslavia, or for the Yugoslav army.[50] He addressed the economic crisis, called for the reneval of a market economy and a parliamentary democracy, and expressed his support for the accession to the European Community. He maintained that Yugoslavia could survive only as a confederation.[51] Although Tuđman had ties with the right-wing anti-Communist diaspora, he also had important colleagues from the Partisan Communist establishment, including Josip Boljkovac and Josip Manolić.[50] His main opponent in the election was Ivica Račan from the League of Communists of Croatia (SKH), who became the SKH Chairman in December 1989.[52]

Tuđman's talk of Croatia's past glories and independence was not received well among Croatian Serbs. The HDZ was heavily criticized by Serbian media, portraying their possible victory as a revival of NDH.[53] Veljko Kadijević, general of the JNA, said at meeting of the army and SR Croatia leaderships that the elections will bring the Ustashe to power in Croatia. A few weeks before the elections, the army removed the weapons of the Territorial Defence from stores all over Croatia.[54] During a HDZ campaign rally in Benkovac, an ethnically mixed town, a 62-year-old Serbian man, Boško Čubrilović, pulled out a gas pistol near the podium. Croatian media described the incident as an assassination attempt on Tuđman, but Čubrilović was in late 1990 charged and convicted only of threatening the security staff. The incident further worsened ethnic tensions.[55]

During his campaign, on 16 April 1990 Tuđman had a conversation with news reporters where he said:

All sorts of other lies are being spread today, I do not know what else they will invent. I've heard that I'm of Jewish descent, but I found, I knew of my ancestors in Zagorje from around 350 years ago, and I said, maybe it would be good to have some of that, I guess I would be richer, I might not have become a Communist. Then, as if that's not enough, then they declare that my wife is Jewish or Serbian. Luckily for me, she never was either, although many wives are. And so on and so forth spreading lies ...[56]

The part of the statement about his wife was later widely criticized, including by officials of the Wiesenthal Center.[57] Croatian historian Ante Nazor cited claims by Tuđman's son, Miroslav and Stijepo Mijović Kočan[who?] about the statement being directed against the former Yugoslav communist system rather than against Jews or Serbs; instead about mixed marriages being used by Croats as a means to promotion in the system.[56] On 19 April, at a rally in Zadar, Tuđman said:[58]

Let them not deceive that we want a restoration of the fascist NDH, which was created and disappeared within the Second World War. We know that the Croatian people also fought during the war on the other side under partisan, Tito's flags because he promised to create a free Federal State of Croatia that would be equal to all other nations. Clearly, instead of a realization of these ideals we received communist hell.

The elections were scheduled for all 356 seats in the parliament. Tuđman's party triumphed and got an absolute majority of around 60% or 205 seats in the Croatian Parliament. Tuđman was elected to the position of President of Croatia on 30 May 1990. After the victory of HDZ the nationalistic Serb Democratic Party (SDS) spread its influence quickly in places where Serbs formed a high percentage of the population.[59] Since the split among communists in Yugoslavia along ethnic lines was already a fact at that time, it seemed inevitable that the conflicts would continue following the multi-party elections which brought to power new political establishments in Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, while at the same time the same communist officials kept their posts in Serbia and Montenegro.[citation needed]

President of Croatia (1990–1999)

In the weeks following the election, the new government introduced the traditional Croatian flag and coat of arms, without Communist symbols. The term "Socialist" in the title of the republic was removed. Constitutional changes were proposed with a multitude of political, economic, and social changes.[60] Tuđman offered the vice-presidency to Jovan Rašković, president of the SDS, but Rašković declined the offer and called the elected deputies from his party to boycott the parliament. Local Serb police in Knin began operating as an independent force, often not responding to orders from Zagreb.[61] Many government employees, mostly in police where commanding positions were mainly held by Serbs and Communists, lost their jobs. This was based on a decision that the civil service ethnic structure should correspond to their percentage in the entire population.[59]

On 25 July 1990, a Serbian Assembly was established in Srb, north of Knin. Jovan Rašković announced a referendum on "Serb sovereignty and autonomy" in Croatia in August 1990, which Tuđman labeled as illegal. A series of incidents followed in areas populated by ethnic Serbs, mostly around Knin, known as the Log Revolution.[62] The revolt in Knin concentrated the Croatian government on the problem of the lack of weapons. The effects of the JNA's confiscation of the Territorial Defence supplies was partly undone by the new Defence Minister, Martin Špegelj, who bought weapons from Hungary.[63] As it had no regular army, the government had focused on building up the police force. By January 1991 there were 18,500 policemen and by April 1991 around 39,000.[64] On 22 December 1990, the Parliament of Croatia ratified the new constitution. The Serbs in Knin proclaimed the Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina in municipalities of the regions of Northern Dalmatia and Lika.[65]

In December 1990 Tuđman and Slovenian President Milan Kučan presented their proposal on the restructuring of Yugoslavia on confederal grounds. Tuđman believed that a confederation of sovereign republics could accelerate the Croatian accession to the European Community.[66] The leaders of the Yugoslav republics held many meetings in early 1991 to resolve the growing crisis. On 25 March 1991, Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević met at Karađorđevo,[67] a meeting which became controversial due to claims that the two presidents discussed the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia. However, the claims came from persons that were not present at the meeting and there is no record of this meeting that proves an existence of such an agreement,[68] while Milošević did not behave subsequently as if he had an agreement with Tuđman.[69] On 12 July 1991, Tuđman met with Izetbegović and Milošević in Split.[67]

War years

On 1 March the Pakrac clash occurred when local Serb police seized the town's police station and declared Pakrac a part of SAO Krajina. It was one of the first larger clashes between Croat forces and the rebel SAO Krajina, supported by the JNA. It ended without casualties and with the restoration of Croatian control.[70] On 31 March a Croatian police convoy was ambushed at the Plitvice Lakes.[71] Until the spring of 1991 Tuđman, together with the Slovenian leadership, was ready to accept a compromise solution of a confederation or alliance of sovereign states within Yugoslavia. After the Serbian leadership rejected their proposals and armed provocations became more frequent, Tuđman decided to realize the idea of a complete Croatian independence.[72] On 25 April 1991, the Croatian Parliament decided to hold an independence referendum on 19 May. Croatian Serbs largely boycotted the referendum.[73] The turnout was 83.56%, of which 93.24% or 2,845,521 voted in favour of the independence of Croatia. Both Slovenia and Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991. The Yugoslav side accused the two of secession. The federal government ordered the JNA to take control of border crossings in Slovenia, which led to the Ten-Day War in which the JNA was routed. The Ten-Day War ended with the signing of the Brioni Agreement, when a three-month moratorium was placed on the implementation of the decision.[72]

The armed incidents of early 1991 escalated into an all-out war over the summer. Tuđman's first plan was to win support from the European Community, avoiding the direct confrontation with the JNA that had been proposed by Martin Špegelj, the Minister of Defence, since the beginning of the conflict.[74] Tuđman rejected Špegelj's proposal as it would be damaging on Croatia's international position and there were doubts that the Croatian army was ready for such an action.[75] The emerging Croatian Army had only four brigades in September 1991.[76] As the war escalated, Tuđman formed the National Unity Government which brought in members of most of the minor parties in the Parliament, including Račan's Social Democratic Party (SDP).[77]

Fierce fighting took place in Vukovar, where around 1,800 Croat fighters were blocking JNA's advance into Slavonia. Vukovar assumed enormous symbolic importance to both sides. Without it, Serbian territorial gains in eastern Slavonia were threatened. The unexpectedly fierce defence of the town against a much larger army inspired talk of a "Croatian Stalingrad". Increasing losses and complaints from the Croatian public for failing to hit back compelled Tuđman to act. He ordered the Croatian National Guard to surround JNA army bases, thus starting the Battle of the Barracks. Tuđman named Gojko Šušak the new Minister of Defence in September 1991.[78]

In early October 1991, the JNA intensified its campaign in Croatia.[79] On 5 October, Tuđman made a speech in which he called upon the whole population to mobilize and defend against "Greater Serbian imperialism" pursued by the Serb-led JNA, Serbian paramilitary formations, and rebel Serb forces. Two days later the Yugoslav Air Force bombed Banski Dvori, the seat of the Croatian Government in Zagreb, at the time when Tuđman had a meeting with Mesić and Marković, none of whom were injured in the attack.[80][81] On 8 October the Croatian Parliament cut all remaining ties with Yugoslavia and declared independence.[81] Tuđman asked the Kosovo leadership to open a second front there against the JNA and offered help in weapons. The leadership decided against armed conflict, but gave support to the independence of Croatia and called on ethnic Albanians to desert the Yugoslav army.[82]

In November 1991 the Battle of Vukovar ended that left the city devastated. The JNA and Serbian irregulars seized control of about a quarter of Croatia's territory by the end of 1991.[83] In December 1991, the SAO Krajina proclaimed itself the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). Until the end of 1991 sixteen ceasefires were signed, none of which lasted longer than a day.[84]

On 19 December 1991, Iceland and Germany recognized Croatia's sovereignty. Many observers believe Tuđman's good relationship with Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Germany's foreign minister at the time, had much to do with this decision.[85] Hostilities in Croatia ended for a time in January 1992 when the Vance plan was signed. Tuđman hoped that the deployment of UN peacekeepers would consolidate Croatia's international borders, but the military situation in Croatia itself remained unsettled.[86]

Bosnian War

As the war in Croatia reached a stalemate, the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina worsened. The JNA used its territory for offensives against Croatia, but avoided the Croat majority part of Herzegovina.[87] Tuđman doubted that Bosnia and Herzegovina could survive the dissolution of Yugoslavia, but supported its integrity if it remained outside a Yugoslav federation and Serbian influence.[88] The first Croat casualties in the country fell in October 1991 when the village of Ravno was attacked and destroyed by the JNA. Several days later Bosnian president Alija Izetbegović gave a televised proclamation of neutrality, stating that "this is not our war".[89][90]

The Bosniak leadership initially showed willingness to remain in a rump Yugoslavia, but later changed their policy and opted for independence.[90] The Croat leadership started organizing themselves in Croat-majority areas and on 18 November 1991 established the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia as an autonomous Croat territorial unit.[91][92] At a meeting in December 1991 with the HDZ BiH leadership Tuđman discussed the possibility of joining Herzeg-Bosnia to Croatia as he thought that Bosnian representatives were working to remain in Yugoslavia. There he criticized HDZ BiH president Stjepan Kljujić for siding with Izetbegović. However, in February 1992 he encouraged Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina to support the upcoming Bosnian independence referendum.[93] Izetbegović declared the country's independence on 6 April that was immediately recognised by Croatia.[94] At the beginning of the Bosnian war a Croat-Bosniak alliance was formed, though it was often not harmonious.[95] The Croatian government helped arm both Croat and Bosniak forces.[96] On 21 July 1992, the Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation was signed by Tuđman and Izetbegović, establishing a military cooperation between the two armies.[97] In September 1992 they signed two more agreements on cooperation and further negotiations regarding the internal organization of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[98] though Izetbegović rejected a military pact.[99] In January 1993 Tuđman said that Bosnia and Herzegovina can survive only as a confederal union of three nations.[100]

Over time, the relations between Croats and Bosniaks worsened, resulting in the Croat–Bosniak War.[101] The Bosniak side claimed that Tuđman wanted to partition Bosnia and Herzegovina, a view that was increasingly accepted by the international community. This made it difficult for Tuđman to protect Croatia's interests and support Herzeg-Bosnia.[99] As the conflict escalated, Croatia's foreign policy reached a low point.[102] Throughout 1993 several peace plans were proposed by the international community. Tuđman and the Herzeg-Bosnia leadership accepted all of them, including the Vance-Owen Plan in January 1993 and the Owen-Stoltenberg in July 1993. However, no lasting ceasefire was agreed.[103] In early 1994 the United States became increasingly involved in resolving the wars. They were concerned with the way the Croat-Bosniak war helped the Serbs and put pressure on the two sides to sign a final truce. The war ended in March 1994 with the signing of the Washington Agreement.[104] In June 1994 Tuđman visited Sarajevo to open the Croatian embassy there. He met with Alija Izetbegović and discussed the creation of the Croat-Muslim Federation and its possible confederation with Croatia.[105]

Ceasefire in Croatia

Despite considerable difficulties, Croatian diplomacy managed to achieve recognition in the following months. Croatia was recognised by the European Community on 15 January 1992 and became a member of the United Nations on 22 May.[85] In April 1992, Washington recognised Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina simultaneously. Since the new Clinton administration came to power it had lobbied consistently for a hard line against Milošević, a political position often largely attributed to the policies of then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.[104] In May 1992 Croatia established diplomatic relations with China. A year later Tuđman was the first president from the former Yugoslavia to visit China.[106]

The war caused great destruction and indirect damage in tourism, transit traffic, investment, etc.[107] President Tuđman estimated the cost of direct material damage at over $20 billion and that Croatia was spending $3 million daily on care for hundreds of thousands of refugees.[108] When the ceasefire of January 1992 came into effect Croatia slowly recovered. As economic activity picked up steadily and negotiations with the leaders of RSK got nowhere, the Defence Minister, Gojko Šušak, started amassing weapons in preparation for a military solution.[109]

Tuđman won the presidential elections in August 1992 in the first round with 57.8% of the vote.[110] Simultaneously, the parliamentary elections were held that were also won by HDZ. During the campaign, Dobroslav Paraga, the extreme right-wing leader of the Croatian Party of Rights, accused Tuđman of betraying Croatian interests by not engaging in an all-out war with Serbian forces. Tuđman tried to marginalize his party due to their use of Ustaše symbols, that brought criticism in the foreign press towards Croatia. Paraga won only 5 seats in the parliament and 5,4% of the vote in the presidential election.[111][112]

In January 1993 the Croatian Army launched Operation Maslenica and recaptured the vital Maslenica bridge linking Dalmatia with northern Croatia. Although the UN Security Council condemned the operation, there were no incurring sanctions. This victory enabled Tuđman to counter domestic accusations that he was weak in his dealings with RSK and the UN.[113]

Despite clashes with the RSK forces, during 1993 and 1994 the overall condition of the economy improved substantially and unemployment was gradually falling. On 4 April 1993 Tuđman appointed Nikica Valentić as prime minister. The anti-inflationary stabilization steps in 1993 successfully lowered inflation. The Croatian dinar, that was introduced as a transitional currency, was replaced with the kuna in 1994.[114] GDP growth reached 5.9% in 1994.[115]

End of the war

In May 1995, the Croatian army launched Operation Flash, its third operation against RSK since the January 1992 ceasefire, and quickly recaptured western Slavonia. International diplomats drafted the Z-4 Plan, proposing the reintegration of the RSK into Croatia. RSK would keep its flag and have its own president, parliament, police and a separate currency. Although Tuđman was displeased with the proposal, RSK authorities rejected it outright.[116]

On 22 July 1995, Tuđman and Izetbegović signed the Split Agreement, binding both sides to a "joint defence against Serb aggression". Tuđman soon put his words into action and initiated Operation Summer '95, carried out by joint forces of HV and HVO. These forces overran the towns of Glamoč and Bosansko Grahovo in western Bosnia, virtually isolating Knin from Republika Srpska and FR Yugoslavia.[117]

At 5:00 a.m. on Friday, 4 August 1995, Tuđman publicly authorized the attack on RSK, codenamed Operation Storm. He called on the Serb army and their leadership in Knin to surrender, and at the same time called Serb civilians to remain in their homes, guaranteeing them their rights. The decision to head straight for Knin, the centre of RSK, paid off and by 10 am on 5 August, on the second day of the operation, Croatian forces entered the city with minimal casualties. By the morning of 8 August the operation was effectively over, resulting in the restoration of Croatian control of 10,400 square kilometres (4,000 square miles) of territory. Around 150,000–200,000 Serbs fled and a variety of crimes were committed against the remaining civilians.[118] United States President Bill Clinton said he was "hopeful that Croatia's offensive will turn out to be something that will give us an avenue to a quick diplomatic solution."[119]

A joint offensive of Croatian and Bosniak forces followed in western and northern Bosnia. Bosnian Serb forces quickly lost territory and were forced to negotiate. Talks regarding a peace treaty were held in Dayton, Ohio.[120] Tuđman insisted on solving the question of RSK-held eastern Slavonia and its peaceful return to Croatia at the Dayton peace talks. On 1 November he had a heated debate with Milošević, who denied control over the region's leadership. Tuđman was ready to hinder the Dayton agreement and continue the war if Slavonia was not peacefully reintegrated. The military situation gave him an upper hand and Milošević agreed on his request.[121] The Dayton Agreement was drafted in November 1995. Tuđman was one of the signatories of it, along with the leaderships of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, that ended the Bosnian War. On 12 November the Erdut Agreement was signed with local Serb authorities regarding the return of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia to Croatia, with a two-year transitional period. This ended the war in Croatia.[122] Official figures on wartime damage published in Croatia in 1996 specify 180,000 destroyed housing units, 25% of the Croatian economy destroyed, and US$27 billion of material damage.[123] Regarding the exodus of some 150,000 Krajina Serbs from Croatia, Tudjman remarked that the refugees left so fast that they "didn't even have time to collect their dirty currency and their dirty underwear".[124] He later boasted to his generals: "We have resolved the Serbian question... [t]here will never be 12 percent of Serbs" in Croatia. "If there are three or five per cent of them, that isn’t a threat to the Croatian state".[125]

Post-war policy

In 1995 parliamentary elections were held that resulted in a victory of HDZ with 75 out of 127 seats in the parliament. Tuđman named Zlatko Mateša the 6th prime minister, who formed the first peacetime government of independent Croatia. The elections were held in conjunction with local elections in Zagreb, which were won by the opposition parties. Tuđman refused to provide a formal confirmation to the proposed Mayor of Zagreb, which led to the Zagreb crisis. In 1996 a large demonstration was held in Zagreb in response to revoking broadcasting license to Radio 101, a radio station that was critical towards the ruling party.[126]

Treatment of the media brought criticism from some international organizations.[126] Notably, the Feral Tribune, a weekly Croatian political and satirical newspaper magazine, was subjected to several lawsuits and criminal charges from government officials as well as being forced to pay a tax usually reserved for pornographic magazines.[127] Some opposition parties in Croatia advocated the view that, far from Europeanising Croatia, Tuđman was responsible for its "Balkanisation" and that during his presidency, he acted like a despot. Other parties, for instance the Croatian Party of Rights, argued that Tuđman was not radical enough in his defence of the Croatian state.[128]

Croatia became a member of the Council of Europe on 6 November 1996.[129] On 15 June 1997 Tuđman won the presidential elections with 61.4% of the votes, ahead of Zdravko Tomac and Vlado Gotovac, and was re-elected to a second five-year term. Marina Matulović-Dropulić became the Mayor of Zagreb having won the 1997 local elections, which formally ended the Zagreb crisis.

In January 1998 Eastern Slavonia was officially reintegrated into Croatia.[130] In February 1998 Tuđman was re-elected as President of HDZ. The beginning of the year was marked by a large syndical protest in Zagreb, due to which the government adopted legislation regulating public gatherings and demonstrations in April.[131] After the war, Tuđman controversially suggested that the remains of those killed during the Bleiburg repatriations be brought and laid to rest at Jasenovac, an idea he later abandoned. This idea included burying Ustaša troops, anti-fascist Partisans and all civilians together and was inspired by General Francisco Franco's Valle de los Caídos.[132] In 1998 Tuđman claimed that his program of national reconciliation had prevented a civil war in Croatia during the collapse of Yugoslavia.[133]

Economy

As a result of the macro-stabilization programs, the negative growth of GDP during the early 1990s stopped and turned into a positive trend. Post-war reconstruction activity provided another impetus to growth. Consumer spending and private sector investments, both of which were postponed during the war, contributed to improved economic conditions and growth in 1995–97.[134] Real GDP growth in 1995 was 6.8%, in 1996 5.9% and in 1997 6.6%.[115]

In 1995 a Ministry of Privatization was established with Ivan Penić as its first minister.[135] Privatization in Croatia had barely begun when war broke out in 1991. Infrastructure sustained massive damage from the war, especially the revenue-rich tourism industry, and its transformation from a planned economy to a market economy was thus slow and unsteady. Public mistrust rose when many state-owned companies were sold to politically well-connected at below-market prices.[134] The ruling party was criticised for transferring enterprises to a group of privileged owners connected to the party.[136]

The method of privatization contributed to the increase of state ownership because the unsold shares were transferred to state funds. In 1999 the private sector share in GDP reached 60%, which was significantly lower than in other former socialist countries.[137] The privatization of large government-owned companies was practically halted during the war and in the years immediately following the conclusion of peace. At the end of Tuđman's rule, roughly 70% of Croatia's major companies were still state-owned, including water, electricity, oil, transportation, telecommunications, and tourism.[138]

Value-added tax was introduced in 1998 and the central government budget was in surplus that year.[139] The consumer boom was disrupted when the economy went into recession at the end of 1998, as a result of the bank crisis when 14 banks went bankrupt,[134] and GDP growth slowed down to 1,9%. The recession continued throughout 1999 when GDP fell by 0,9%.[115] Unemployment increased from around 10% in 1996 and 1997 to 11,4% in 1998. By the end of 1999 it reached 13,6%. The country emerged from the recession in the 4th quarter of 1999.[140] After several years of successful macroeconomic stabilization policies, low inflation and a stable currency, economists warned that the lack of fiscal changes and the expanding role of the state in economy caused the decline in the late 1990s and were preventing a sustainable economic growth.[140][141]

Foreign policy

Mate Granić was the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1993 until the end of the Tuđman administration. In 1996 he signed an agreement on normalization of relations with FR Yugoslavia.[142] On 9 September 1996 Croatia established diplomatic relations with FR Yugoslavia.

The US was the main mediator in reaching a peace treaty in the region and continued to have most influence after 1995.[143] The Croatian offensives in 1995 did not receive unambiguous supports from the US, but they supported Croatian demands for territorial integrity. However, the Croatian-American relations after the war did not develop as Tuđman expected. Serb minority rights and cooperation with the ICTY were asserted as the main issues and they led to a deterioration of relations at the end of 1996 and during 1997.[144] Tuđman tried to counter the pressure with closer relations with Russia and China.[145] In November 1996 he received the Medal of Zhukov, awarded for contribution to the antifascist struggle, from Russian President Boris Yeltsin.[146]

A confederation between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, adopted under the Washington Agreement, was not accomplished,[147] while the Croat-Bosniak Federation acted only on paper. In August 1996 Tuđman and Izetbegović agreed to fully implement the Dayton agreement. Herzeg-Bosnia was to be formally abolished by the end of the month.[148]

In 1999 the NATO intervention in Kosovo began. Tuđman expressed his concerns regarding the potential damage to Croatian economy and tourism, which was estimated at $1 billion. Still, the government expressed their support to NATO and granted permission to NATO planes to use Croatia's airspace. In May, Tuđman said that a possible solution is to deploy UN peacekeepers in Kosovo that would enable the return of Albanian refugees, while Yugoslav forces would retreat to Serb-majority northern Kosovo.[149]

Relation to the Catholic Church

Živko Kustić, a Croatian Eastern Catholic priest and journalist for Jutarnji list, wrote that Tuđman's perception of the church's role in Croatia was contradictory to the goals of Pope John Paul II. Moreover, Kustić expressed doubt that Tuđman had ever been truly religious except when he was very young. Tuđman considered the Catholic religion to be important for the modern Croatian nation. When taking the oath in 1992 he added sentence "Tako mi Bog pomogao!" (English: So help me God) which was not then part of the official text.[150] In 1997, he officially included the sentence in the oath.[150] Tuđman's era was the era of the Catholic revival in Croatia. Church attendance rose; even former communists massively participated in church sacraments. The state was funding the building and renewal of churches and monasteries. Between 1996 and 1998 Croatia signed various treaties with the Holy See, by which the Catholic Church in Croatia was granted some financial rights, among others.[151]

Health problems and death

Tuđman was diagnosed with cancer in 1993. His general health had deteriorated by the late 1990s. On 1 November 1999 he appeared in public for the last time. While being hospitalized opposition parties accused the ruling HDZ of hiding the fact that Tuđman was already dead and that the authorities were keeping his death secret in order to win more seats in the upcoming January 2000 general election. Tuđman's death was officially declared on 10 December 1999.[152] He had a funeral Mass in Zagreb's Cathedral and was buried in Mirogoj Cemetery.

Vrhovnik

Tuđman was conferred by the Croatian Parliament the military rank of Supreme commander of Croatia, or 'Vrhovnik' on 22 March 1995.[153][154] It was the highest honorific title in the Croatian Armed Forces and equivalent to Marshal.[155] Tuđman was the only person to ever hold this rank.[citation needed] He held it until his death. The uniform for this position allegedly was modeled on the uniform of Josip Broz Tito as Tuđman was Major General of Yugoslav People's Army.[156] The title was eventually abolished in 2002.[157]

ICTY

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established by the United Nations in 1993. Although the Croatian government passed a law on cooperation with the ICTY, since 1997 relations between ICTY and Croatia worsened. Tuđman criticized the work of ICTY in 1999, while ICTY's chief prosecutor Louise Arbour expressed her dissatisfaction with Croatia's cooperation with the Tribunal.[158]

During Tuđman's life, neither Richard Goldstone nor Arbour, ICTY's first chief prosecutors, reportedly considered indicting him. In 2002 the new ICTY prosecutor, Carla del Ponte, said in an interview that she would have indicted Tuđman had he not died in 1999.[159] Graham Blewitt, a senior Tribunal prosecutor, told the AFP wire service that "There would have been sufficient evidence to indict president Tuđman had he still been alive".[160]

In 2000, British Channel 4 television broadcast a report about the tape recordings of Franjo Tuđman in which he allegedly spoke about the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Serbs after the Dayton Agreement. They claimed that the then Croatian President Stjepan Mesić gave them access to 17,000 transcripts. Mesić, who succeeded Tuđman as president of Croatia, and his Office denied giving any transcripts to British journalists and called the report a "sensationalistic story that has nothing to do with the truth".[161]

At the trial of Gotovina, in a first-degree verdict, the Trial Chamber found Tuđman to have been a key participant in a joint criminal enterprise, the purpose of which was to permanently remove the Serb civilian population from the territory of Republic of Serbian Krajina and repopulate it with Croats.[162] In November 2012, an ICTY appeal court overturned the convictions of Mladen Markač and Ante Gotovina, acquitted the two former generals and concluded that there was no planned deportation of the Serbian minority and no joint criminal enterprise by the Croatian leadership.[163]

In May 2013, the ICTY, in a first-instance verdict in the trial of Prlić et al., found that Tuđman, Bobetko and Šušak took part in the joint criminal enterprise against the non-Croat population of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It ruled, by a majority, that the purpose of it was to de facto join Herzeg-Bosnia to Croatia.[164] Judge Jean-Claude Antoanetti, the presiding judge in the trial, issued a separate opinion in which he contested the notion of a joint criminal enterprise and said that Tuđman's plans regarding Bosnia and Herzegovina were not in contradiction with the stance of the international community.[165][166] On 19 July 2016 the Appeals Chamber in the case announced that the "Trial Chamber made no explicit findings concerning [Tudjman's, Šušak's and Bobetko's] participation in the JCE and did not find [them] guilty of any crimes."[167][168] On 29 November 2017, the Appeals Chamber in the case affirmed that none of the crimes were attributed to Tuđman, but upheld the convictions of six Herzeg-Bosnia and HVO leaders and concluded that Tuđman shared the ultimate purpose of "setting up a Croatian entity that reconstituted earlier borders and that facilitated the reunification of the Croatian people".[169]

Tuđman as historian

Tuđman did not have a formal academic education as historian.[170] He approached history as a Marxist scholar and Croatian attorney.[171] He always regarded history as a means of forming society.[172] His voluminous, more than 2,000 pages long, Hrvatska u monarhističkoj Jugoslaviji (English: Croatia in Monarchist Yugoslavia), has come to be assigned as reading material[173] concerning this period of Croatian history at some Croatian universities. His shorter treatises on national question, Nacionalno pitanje u suvremenoj Europi (English: The National question in contemporary Europe) and Usudbene povijestice (English: History's fates) are still well-regarded essays on unresolved national and ethnic disputes, self-determination and creation of nation-states in the European milieu.[citation needed]

Horrors of War

In 1989 Tuđman published Bespuća povijesne zbiljnosti (Literal English translation:Wastelands of historical reality)[174] which was published in English in 1996 as Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy.[175] The book questioned the different claimed numbers of victims killed during World War II in Yugoslavia.[citation needed] Some Serbian historians placed the number of Serbs killed in the Jasenovac concentration camp at 300,000–800,000, although these figures are exaggerated.[176][177]

The last serious research of victim numbers before the Yugoslav wars was conducted by Croatian economist Vladimir Žerjavić and Serbian researcher Bogoljub Kočović. Both Žerjavić and Kočović arrived at a figure of 83,000 deaths in Jasenovac, each using different statistical methods.[178] 59,589 victims (of all nationalities) were identified by name in a Yugoslav name list that was made in 1964.[179] In his book Tuđman had estimated, relying on some earlier investigations, that the total number of victims in the Jasenovac camp (Serbs, Jews, Gypsies, Croats, and others) was somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000.[180][181] He listed the victims as "Gypsies, Jews and Serbs, and even Croatians", reversing the conventional order of deaths to imply that more Gypsies and Jews were killed than Serbs.[182] Tuđman emphasized that the camp was organised as a "work camp".[183] He estimated that a total of 50,000 were killed in all Ustashe camps throughout the NDH.[182]

In Horrors of War, Tuđman accepted historian Gerald Reitlinger's estimates that the number of Jewish deaths during World War II was closer to 4 million as opposed to the most quoted number of 5 to 6 million.[184] Aside from the war statistics issue, Tuđman's book contained views on the Jewish role in history that many readers found simplistic and profoundly biased. Tuđman based his views on the Jewish condition on the memoirs of a Croatian former Communist Ante Ciliga, who described his experiences at Jasenovac during a year and a half of his incarceration. These are recorded in his book, Sam kroz Europu u ratu (1939–1945), paint an unfavorable picture of his Jewish inmates' behavior, emphasizing their alleged clannishness and ethnocentrism. Ciliga claimed Jews had held a privileged position in Jasenovac and actually, as Tuđman concludes, "held in their hands the inmates management of the camp up to 1944 [because] in its origins Pavelić's party was philo-Semitic". Ciliga theorized that the behavior of the Jews had been determined by the more-than-2000-year-old tradition of extreme ethnic egoism and unscrupulousness that he claims is expressed in the Old Testament.[185]

He summarized, among other things, that "The Jews provoke envy and hatred but actually they are 'the unhappiest nation in the world', always victims of 'their own and others' ambitions', and whoever tries to show that they are themselves their own source of tragedy is ranked among the anti-Semites and the object of hatred by the Jews".[186] In another part of the book, Tuđman expressed the belief that these traits weren't unique to the Jews; while criticizing what he alleges to be aggression and atrocities in the Middle East on the part of Israel, he claimed that they arose "from historical unreasonableness and narrowness in which Jewry certainly is no exception".[187]

On 22 April 1998, Tuđman received the credentials of the first Israeli ambassador to Croatia, Natan Meron. In his speech Tuđman said, among other things:

During the Second World War, within the Quisling regime in Croatia, Holocaust crimes were also committed against members of the Jewish people. The Croatian public then, during WWII, and today, including the Croatian government and me personally, have condemned the crimes that the Ustaše committed not only against Jews but also against democratic Croats and even against members of other nations in the Independent State of Croatia.[188]

Legacy

Mr. President, like all the great people during life you will not wait enough for the proper interpretation of your merits for the nation, it will be done only by future generations, but believe me it will be done. You'll be a great man of Croatian history, but not during your life, but when ratings will be made with cool heads.

— Henry Kissinger, [189]

Tuđman is credited by his supporters with creating the basis for an independent Croatia, and helping the country move away from communism. He is sometimes given the title "father of the country" for his role in achieving the country's independence. His legacy is still strong in many parts of Croatia as well as in parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina with Croatian majorities; there are schools, squares and streets in some cities named after him, and statues have been erected. In December 2006, a large square near Ilica Street in the Črnomerec section of Zagreb was named after him.[190] In June 2015 Siniša Hajdaš Dončić, Minister of Maritime Affairs Transport and Infrastructure, said that the reconstructed and upgraded Zagreb International Airport will be named after Tuđman.[191]

His tenure as president was criticized as authoritarian by some observers.[179][192][193] Goldstein views Tudjman's post-war policies negatively, remarking that "between healthy nationalism and chauvinism, he chose chauvinism; between free-market economy and clientelism, he chose the latter. Instead of the cult of freedom, he chose the cult of the state. Between modernity and openness to the world, he chose traditionalism; a fatal choice for a small state like Croatia that needs to open for the sake of development".[175]

Public opinion

Tuđman's approval ratings remained largely positive throughout his presidency and were generally evaluated higher than the rest of the government. They increased significantly following the admission of Croatia to membership in the United Nations in May 1992, the successful military operations in January 1993 and August 1995, and the peaceful reintegration of eastern Slavonia in January 1998. Polls showed a drop in support in the second half of 1993, throughout 1994 and in 1996. From early 1998 his approval gradually declined, before increasing slightly in November 1999.[194]

In a December 2002 poll by HRT, 69% voters expressed a positive opinion about Tuđman.[195]

In a June 2011 poll by Večernji list, 62% voters gave the most credit to Tuđman for the creation of independent Croatia.[196] In December 2014, an Ipsos Puls survey on 600 people showed that 56% see him as a positive figure, 27% said he had both positive and negative aspects, while 14% regard him as a negative figure.[197]

In a survey by promocija Plus in July 2015, regarding the renaming of Zagreb Airport after Tuđman, a majority of 65.5% showed support for the initiative, 25.8% were opposed to the idea, while 8.6% had no opinion about it.[198]

| Date | Event | Approval (%) |

|---|---|---|

| December 1991 | 69 | |

| May 1992 | Croatia accepted into the UN | 77 |

| July 1992 | 71 | |

| January 1993 | Operation Maslenica | 76 |

| May 1993 | 61 | |

| December 1994 | 55 | |

| August 1995 | Operation Storm | 85 |

| October 1996 | 60 | |

| July 1997 | Re-elected president | 65 |

| February 1998 | 50 | |

| October 1998 | 44 | |

| November 1999 | 45 |

Immediate family

- Widow: Ankica Tuđman (born 1926)

- Sons: Miroslav Tuđman (1946–2021)[199][200] and Stjepan Tuđman

- Daughter: Nevenka Tuđman (born 1951)[201]

Honours and decorations

Croatian

Awarded by the Croatian Parliament in 1995:[202]

Military rank

| Award or decoration | |

|---|---|

|

Vrhovnik of the Croatian Armed Forces |

International

This section does not cite any sources. (December 2019) |

| Award or decoration | Country | Awarded by | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy | Francesco Cossiga | 17 January 1992 | Zagreb | ||

| Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of Chile | Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle | 29 November 1994 | Santiago de Chile | ||

|

Collar of the Order of the Liberator San Martin | Carlos Menem | 1 December 1994 | Buenos Aires | |

| Medal of Zhukov | Boris Yeltsin | 4 November 1996 | Zagreb | ||

| Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer | Konstantinos Stephanopoulos | 23 November 1998 | Athens | ||

| Order of the State of Republic of Turkey | Suleyman Demirel | 1999 | Zagreb | ||

Notes

- Bing, Albert (October 2008). "Sjedinjene Američke Države i reintegracija hrvatskog Podunavlja" [The United States of America and the reintegration of the Croatian Danube Region]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 8 (1): 336–365.

- Buckley, Mary E. A.; Cummings, Sally N. (2001). Kosovo: perceptions of war and its aftermath. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-5670-0.

- Christia, Fotini (2012). Alliance Formation in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13985-175-6.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-525-1.

- Holbrooke, Richard (1999). To End a War. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-75360-2.

- Hudelist, Darko (2004). Tuđman – biografija (in Croatian). Zagreb: Profil. ISBN 953-12-0038-6.

- Krišto, Jure (April 2011). "Deconstructing a myth: Franjo Tuđman and Bosnia and Herzegovina". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 6 (1): 37–66.

- Lamza Posavec, Vesna (July 2000). "Što je prethodilo neuspjehu HDZ-a na izborima 2000.: Rezultati istraživanja javnoga mnijenja u razdoblju od 1991. do 1999. godine" [What Preceded HDZ's Failure at the 2000 Elections: Results of Public Opinion Polis from 1991 to 1999]. Društvena Istraživanja : časopis Za Opća Društvena Pitanja (in Croatian). Institut društvenih znanosti Ivo Pilar. 9 (4–5): 433–471.

- Macdonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centered Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719064678.

- Marijan, Davor (2004). Bitka za Vukovar [Battle of Vukovar] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatski institut za povijest. ISBN 9789536324453.

- Marijan, Davor (2004). "Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991 – 1995)". Journal of Contemporary History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 36: 249–289.

- Marijan, Davor (June 2008). "Sudionici i osnovne značajke rata u Hrvatskoj 1990. – 1991" [Participants and the basic characteristics of the war in Croatia 1990–1991]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 40 (1): 47–63. ISSN 0590-9597.

- Mrduljaš, Saša (2008). "Politička dimenzija hrvatsko-muslimanskih/bošnjačkih odnosa tijekom 1992. godine" [Political dimension of Croat-Muslim/Bosniak relations during 1992]. Journal for General Social Issues (in Croatian). Split, Croatia: Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar. 17: 847–868.

- Nazor, Ante (2001). The town was the target (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Memorial Documentation Centre of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia.

- Phillips, David L.; Burns, Nicholas (2012). Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U.S. Intervention. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-30512-9.

- Radelić, Zdenko (2006). Hrvatska u Jugoslaviji 1945. – 1991 (in Croatian). Zagreb: Školska knjiga. ISBN 953-0-60816-0.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Sadkovich, James J. (2010). Tuđman – Prva politička biografija (in Croatian). Zagreb: Večernji list. ISBN 978-953-7313-72-2.

- Sadkovich, James J. (January 2007). "Franjo Tuđman and the Muslim-Croat War of 1993". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 2 (1): 204–245. ISSN 1845-4380.

- Sadkovich, James J. (June 2008). "Franjo Tuđman i problem stvaranja hrvatske države" [Franjo Tuđman and the problem of creating a Croatian State]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 40 (1): 177–194. ISSN 0590-9597.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia : a nation forged in war (2nd ed.). New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09125-7.

- Tuđman, Franjo (1989). Bespuća povijesne zbiljnosti : rasprava o povijesti i filozofiji zlosilja (in Croatian) (2nd ed.). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. ISBN 978-86-401-0042-7.

References

- ^ "ODLUKA O OZNAKAMA ČINOVA I DUŽNOSTI U ORUŽANIM SNAGAMA REPUBLIKE HRVATSKE" (in Croatian). Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Rank Vrhovnik". ZASTUPNIČKI DOM SABORA REPUBLIKE HRVATSKE. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Franjo Tudjman". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (12 December 1999). "Franjo Tudjman". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Žanić, Ivo. 2002. "South Slav Traditional Culture as a Means to Political Legitimization." In: Sanimir Resić and Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (eds.), The Balkans in Focus. Cultural Boundaries in Europe, pp. 45–58. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, p. 53.

- ^ Krile, A.B. "Počasti i polemike oko rodne kuće." Slobodna Dalmacija (15 May 2003).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sadkovich 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hudelist 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 37.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Sadkovich 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Sadkovich 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sadkovich 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Radelić 2006, p. 397.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hudelist 2004, p. 211.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 212.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 213.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 215.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 217.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 207.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadkovich 2010, p. 82.

- ^ Obituary, theguardian.com; accessed 19 July 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Tudjman, Franjo". Istrapedia (in Croatian). Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadkovich 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sadkovich 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Hudelist 2004, p. 401.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 147.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadkovich 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Franjo Tuđman". Moljac.hr. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Franjo Tuđman's statement on YouTube on YouTube, ... s kim sam i ja bio prijatelj, i koji me na kraju spasio od progona njegovog vlastitog komunističkog režima." ("... [Tito] was a friend who in the end saved me from the persecution of his own communist regime")

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 204.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadkovich 2010, p. 219.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 232.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 248.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 250.

- ^ "The Communist Partisans led by Tito are said to have killed his father, an Ustashe officer, three months later and burned the Susak house to the ground. An elder brother was also an Ustashe officer.", nytimes.com, 5 May 1998; accessed 20 July 2015.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 247.

- ^ Davor Domazet-Lošo. "How Aggression Against Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina Was Prepared or the Transformation of the JNA into a Serbian Imperial Force" (PDF). National Security and the Future. 1 (1, Spring 2000): 107–152. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 242.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 222.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanner 2001, p. 223.

- ^ Sadkovich 2008, p. 180.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 221.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 224.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 227.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ante Nazor (26 January 2013). "Laž je da Tuđman 'izbacio' Srbe iz Ustava" [The lie is that Tuđman 'banned' Serbs from the Constitution] (in Croatian). Dnevno.hr. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Schemo, Diana Jean (22 April 1993). "Anger Greets Croatian's Invitation To Holocaust Museum Dedication". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "Predizborni skup HDZ-a u Zadru 19. travnja". Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goldstein 1999, p. 215.

- ^ Nazor 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 262.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 232.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 235.

- ^ Marijan 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 219.

- ^ Sadkovich 2008, p. 182.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sadkovich 2007, p. 239.

- ^ Sadkovich 2010, p. 393.

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 264.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 241.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 243.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goldstein 1999, p. 226.

- ^ Sudetic, Chuck (20 May 1991). "Croatia Votes for Sovereignty and Confederation". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 250.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 227.

- ^ Sadkovich 2008, p. 188.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 253.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 256.

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 263.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 233.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nazor 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Phillips & Burns 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 277.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 231.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanner 2001, p. 274.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 279-281.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 252.

- ^ Sadkovich 2007, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Krišto 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Krišto 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 259.

- ^ Krišto 2011, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 285.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 154.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 266.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 243.

- ^ Mrduljaš 2008, p. 859.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Krišto 2011, p. 51.

- ^ Mrduljaš 2008, p. 862.

- ^ Christia 2012, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 247.

- ^ Sadkovich 2007, p. 218.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanner 2001, p. 292.

- ^ "Croatian President Visits Sarajevo". chicagotribune. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Baković 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 236.

- ^ Jane Shapiro Zacek, Ilpyong J. Kim: The Legacy of the Soviet Bloc, University Press of Florida, 1997, p. 130

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 284.

- ^ Nohlen, Dieter & P. Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p. 410

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 265.

- ^ Charles Vance, Yongsun Paik: Managing a Global Workforce: Challenges and Opportunities in International Human Resource Management, M.E. Sharpe, 2006, p. 614

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 288.

- ^ Istvan Benczes: Deficit and Debt in Transition: The Political Economy of Public Finances in Central and Eastern Europe, Central European University Press, 2014, p. 203

- ^ Jump up to: a b c National Accounts Main Aggregates Database

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 294.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 296.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 297.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 298.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Holbrooke 1999, p. 237.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 255-256.

- ^ Darko Zubrinic. "Croatia within ex-Yugoslavia". Croatianhistory.net. Retrieved 7 February 2010.[better source needed]

- ^ Cohen, Roger (3 September 1995). "The World; Finally Torn Apart, The Balkans Can Hope". The New York Times.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal (2013). Genocide, Ethnonationalism, and the United Nations: Exploring the Causes of Mass Killing Since 1945. Routledge. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-13629-799-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ramet 2010, p. 273.

- ^ "Tudjman tries to silence accusers". The Irish Times. 2 June 1998.

- ^ Bellamy, Alex J. (2003). The formation of Croatian national identity: a centuries-old dream. Manchester University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-7190-6502-X. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Chronology of Croatia's accession to the Council of Europe". mvep.hr. Republic of Croatia Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs.

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 277.

- ^ Taylor & Francis Group: Europa World Year, Taylor & Francis, 2004, p. 1339

- ^ Milekic, Sven (11 October 2017). "Why Croatia's President Tudjman Imitated General Franco". BalkanInsight.com. BIRN.

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 267.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c International Business Publications: Croatia Investment and Trade Laws and Regulations Handbook, p. 22

- ^ William Bartlett: Europe's Troubled Region: Economic Development, Institutional Reform, and Social Welfare in the Western Balkans, Routledge, 2007, p. 18

- ^ William Bartlett: Europe's Troubled Region: Economic Development, Institutional Reform, and Social Welfare in the Western Balkans, Routledge, 2007, p. 66

- ^ Istvan Benczes. Deficit and Debt in Transition: The Political Economy of Public Finances in Central and Eastern Europe, Central European University Press, 2014, pp. 205-06.

- ^ Ellington, Lucien (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 473. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- ^ OECD: Agricultural Policies in Emerging and Transition Economies 1999, p. 43

- ^ Jump up to: a b Istvan Benczes:Deficit and Debt in Transition: The Political Economy of Public Finances in Central and Eastern Europe, Central European University Press, 2014, p. 207

- ^ Gale Research: Countries of the World and Their Leaders: Yearbook 2001, p. 456

- ^ "VL biografije - Mate Granić". Večernji list.

- ^ Bing 2008, p. 339.

- ^ Bing 2008, pp. 343–345.

- ^ Baković 2000, p. 66.

- ^ "Odlikovanja predsjednika Hrvatske dr. Franje Tuđmana". Croatian Radio Television. 12 December 1999. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010.

- ^ Krišto 2011, pp. 57–58.

- ^ "Muslim and Croatian Leaders Approve Federation for Bosnia". New York Times. 15 August 1996.

- ^ Buckley & Cummings 2001, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Živko Kustić | Irreverent Impiety". Impious.wordpress.com. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Concordat Watch - Croatia". Concordatwatch.eu. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Croats mourn Croatian president". BBC News. 11 December 1999.

His organs did not function properly, he was taken off the life support system he had been attached to since his November surgery. Tudjman died at 23:14 (22:14 GMT) on Friday [10 Dec] at the Dubrava clinic in the capital Zagreb, a government spokesman said.

Death of Tudjman, cnn.com; 13 December 1999; accessed 16 May 2015. - ^ "Odluku o proglašenju zakona o službi u oružanim snagama Republike Hrvatske". Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ "VRHOVNIK CISTI HRVATSKU VOJSKU". Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ "Prevodenje Vojnih Pojmova: Nazivi Cinova, Duznosti, Polozaja I Zvanja" (PDF). Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Binder, David (11 December 1999). "Tudjman Is Dead; Croat Led Country Out of Yugoslavia". New York Times.

- ^ "Odluku O Proglašenju Zakona O Službi U Oružanim Snagama Republike Hrvatske" (PDF). Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Alan Carling: Globalization and Identity: Development and Integration in a Changing World, I.B. Tauris, 2006, p. 170

- ^ Klaus Bachmann, Aleksandar Fatić: The UN International Criminal Tribunals: Transition Without Justice?, Routledge, 2015, p. 131

- ^ "Tudjman would have been charged by war crimes tribunal". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 10 November 2000. Retrieved 23 December 2008.