United Macedonia

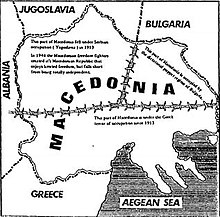

United Macedonia (Macedonian: Обединета Македонија, Obedineta Makedonija), or Greater Macedonia (Голема Македонија, Golema Makedonija), is an irredentist concept among ethnic Macedonian nationalists that aims to unify the transnational region of Macedonia in Southeastern Europe (which they claim as their homeland and which they assert was unjustly divided under the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913) into a single state that would be dominated by ethnic Macedonians. The proposed capital of such a United Macedonia is the city of Thessaloniki (Solun in the Slavic languages), the capital of Greek Macedonia, which ethnic Macedonians and the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito had planned to incorporate into their own states (along with the hinterland of Greek Macedonia, which they came to call Aegean Macedonia).[1][2]

History of the concept[]

The roots of the concept can be traced back to 1910 First Balkan Socialist Conference as a possible solution of the Macedonian Question. Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian politician, writes in 1915 that the creation of a "Macedonia, which was split into three parts, was to be reunited into a single state enjoying equal rights within the framework of the Balkan Democratic Federation".[3] In 1924, the Communist International suggested that all Balkan communist parties adopt a platform of a "united Macedonia" but the suggestion was rejected by the Bulgarian and Greek communists.[4] In 1934 the Comintern issued an official political document, in which for the first time, an authoritative international organization has recognized the existence of a separate Macedonian people and a Macedonian language.

According to the Yugoslav communist Svetozar Vukmanović, the slogan about an united Macedonia appeared in the manifesto of the HQ of the National Liberation Army of Macedonia, at the beginning of October 1943.[5] At that time Vukmanović was sent by Tito to macedonianize the Communist struggle in Macedonia, and to give it a new ethnic-Macedonian facade. One of his main achievements was that wartime pro-Bulgarian sentiments of the local communists to be receded into pro-Yugoslavism. As result the pro-Bulgarian Regional Committee of Communists in Macedonia was dissolved and replaced by a new Communist Party of Macedonia, as part of the Yugoslav Communist Party.[6]

The Yugoslav communists recognized the separate Macedonian nationality to reduce the fears of the Macedonian Slavic population that they would continue the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. They didn't support the view that the Macedonian Slavs are Bulgarians, because that meant in practice, the area should remain part of the Bulgaria after the war.[7] Afterwards the Yugoslav communists proclaimed as their aim the unification of Macedonia's three regions (Yugoslav, Greek and Bulgarian), thus attracting the Macedonian nationalists.

During the following operations of the National Liberation War of Macedonia the Macedonian Communist combatants developed aspirations over the geographic region of Macedonia that continued after 1944 during the Greek Civil War. The Bled agreement (1947) signed by the communist leaders Georgi Dimitrov and Josip Broz Tito also foresaw the unification of Yugoslav and Bulgarian Macedonia. It was also the first time that Bulgaria recognized ethnic Macedonians and the Macedonian language. After the Tito–Stalin split in 1948 and the death of Dimitrov in 1949, in the same year the communists lost the Civil War in Greece. That put to an end the practical application of the concept.

After the breakup of Yugoslavia[]

Since 1989, ethnic Macedonian nationalists have called for a "United Macedonia", stating that "Solun (Thessaloniki) is ours" and "We fight for a United Macedonia".[8][9] Several maps depicting "United Macedonia" as an independent country, stating irredentist claims of the Macedonian nationalists against both Greek and Bulgarian territory, circulated since the late 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. In one of those maps all of Mount Olympus was incorporated in the territory of "United Macedonia".[10] The Macedonian nationalists[11] break down the region of Macedonia as follows:

- Vardar Macedonia (Вардарска Македонија) which includes:

- the territory of North Macedonia;

- Gora (Гора), small portions of southern Kosovo and eastern Albania

- Prohor Pčinski (Прохор Пчински), southern Serbia; and

- Greek Macedonia (or "Aegean Macedonia", "Егејска Македонија"), northern Greece;

- Blagoevgrad Province (or "Pirin Macedonia", "Пиринска Македонија"), southwestern Bulgaria; and

- Mala Prespa and Golo Brdo (Мала Преспа и Голо Брдо), Albania.

Macedonian nationalists describe the above areas as the unliberated parts of Macedonia and they claim that the majority of the population in those territories are oppressed ethnic Macedonians. In the cases of Bulgaria and Albania, it is said that they are undercounted in the censuses (In Albania, there are officially 5,000 ethnic Macedonians, whereas Macedonians nationalists claim the figures are more like 120,000-350,000.[12] In Bulgaria, there are officially 1,600 ethnic Macedonians, whereas Macedonian nationalists claim 200,000[13]). In Greece, there is a Slavic-speaking minority with various self-identifications (Macedonian, Greek, Bulgarian), estimated by Ethnologue and the as being between 100,000-200,000 (according to the Greek Helsinki Monitor only an estimated 10,000-30,000 have an ethnic Macedonian national identity[14]). The government of North Macedonia, led by nationalist party VMRO-DPMNE, claimed[when?] that there is an ethnic Macedonian minority numbering up to 750,000 in Bulgaria and 700,000 in Greece.[15] The idea of a united Macedonia under communist rule was abandoned in 1948 when the Greek communists lost in the Greek Civil War, and Tito fell out with the Soviet Union and pro-Soviet Bulgaria.

In its first resolution, VMRO-DPMNE, the nationalistic[16][17][18][19][20][21][22] governing party at the time of the then-Republic of Macedonia, adopted the platform of a "United Macedonia",[23] an act that has annoyed moderate ethnic Macedonian politicians and has also been regarded by Greece as an intolerable irredentist claim against Greek Macedonia.[24]

Before and just after independence, it was assumed in Greece that the idea of a united Macedonia was still state-sponsored. In the Constitution of the Republic of Macedonia, adopted on 17 November 1991, Article 49 read as follows:[25]

- (1) The Republic cares for the status and rights of those persons belonging to the Macedonian people in neighbouring countries, as well as Macedonian expatriates, assists their cultural development and promotes links with them.

- (2) The Republic cares for the cultural, economic and social rights of the citizens of the Republic abroad.

On 13 September 1995, the Republic of Macedonia signed an interim accord with Greece[26] in order to end the economic embargo Greece had imposed, among other reasons, for the perceived land claims. Among its provisions, the Accord specified that the Republic of Macedonia would renounce all land claims to neighbouring states' territories.

The United Macedonia concept was still found among official sources in North Macedonia,[27][28][29] and taught in schools through school textbooks and through other governmental publications.[30][31]

See also[]

- Macedonian nationalism

- Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople regions

- Independent Macedonia

- Independent Macedonia (1944)

- Vardar Macedonia

- Macedonia naming dispute

- Macedonia (terminology)

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- History of North Macedonia

- Titoism

References[]

- ^ Greek Macedonia "not a problem", The Times (London), August 5, 1957

- ^ A large assembly of people during the inauguration of the Horseman in Skopje, the players of the national basketball team of the Republic of North Macedonia during the European Basketball Championship in Lithuania, and a little girl, singing a nationalistic tune called Izlezi Momče (Излези момче, "Get out boy"). Translation from Macedonian:

"Get out, boy, straight on the terrace

And salute Goce's race

Raise your hands up high

Ours will be Thessaloniki's area." - ^ Dimitrov, Georgi. "The Significance of the Second Balkan Conference". Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ^ Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Praeger, 2002 p.100

- ^ Svetozar Vukmanovic, Struggle for the Balkans. London, Merlin Press 1980, 1990. Page 213

- ^ Tchavdar Marinov and Alexander Vezenkov, "Communism and Nationalism in the Balkans: Marriage of Convenience or Mutual Attraction?" in Entangled Histories of the Balkans vol. 2, ISBN 9789004261914, Brill Publishers, 2013, pp. 469–555.

- ^ Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- ^ John Phillips, Macedonia: warlords and rebels in the Balkans, I B Tauris Academic, 2002, p.53

- ^ Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, The Balkans: a post-communist history, Routledge, 2006, p. 410

- ^ Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Princeton University Press, 1997, pp. 178, 182

- ^ Janusz Bugajski, Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations and Parties, Sharpe, M. E. Inc., 1994, p. 114

- ^ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Albania : Macedonians

- ^ CIA WORLD FACTBOOK 1992 via the Libraries of the Univ. of Missouri-St. Louis

- ^ "Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (along guidelines for state reports according to Article 25.1 of the Convention)". Greek Helsinki Monitor. 18 September 1999.

- ^ "Macedonia erases 'irredentist' claims as Commission tables report". euroactiv. 17 April 2013.

- ^ Alan John Day, Political parties of the world, 2002

- ^ Hugh Poulton, Who are the Macedonians?, Hurst & Company, 2000

- ^ Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Princeton University Press, 1997

- ^ Christopher K. Lamont, International Criminal Justice and the Politics of Compliance, Ashgate, 2010

- ^ Human Rights Watch World Report, 1999

- ^ Imogen Bell, Central and South-Eastern Europe 2004, Routledge

- ^ Keith Brown, The past in question: modern Macedonia and the uncertainties of nation, Princeton University Press, 2003

- ^ Michael E. Brown, Richard N. Rosecrance, The costs of conflict: prevention and cure in the global arena, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999, p.133

- ^ Alice Ackermann, Making peace prevail: preventing violent conflict in Macedonia, Syracuse University Press, 2000, p.96

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Macedonia Archived 2006-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, adopted 17 November 1991, amended on 6 January 1992.

- ^ "Interim Accord between the Hellenic Republic and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", United Nations, 13 September 1995.

- ^ Lenkova, M. (1999). Dimitras, P.; Papanikolatos, N.; Law, C. (eds.). "Greek Helsinki Monitor: Macedonians of Bulgaria" (PDF). Minorities in Southeast Europe. Greek Helsinki Monitor, Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe — Southeast Europe. Retrieved July 24, 2006.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (February 3, 1992). "As Republic Flexes, Greeks Tense Up". New York Times.

- ^ Danforth, Loring M. How can a woman give birth to one Greek and one Macedonian?. The construction of national identity among immigrants to Australia from Northern Greece. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ Facts About the Republic of Macedonia - annual booklets since 1992, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Secretariat of Information, Second edition, 1997, ISBN 9989-42-044-0. p.14. 2 August 1944.

- ^ Macedonianism: Macedonia's expansionist designs against Greece after the Interim Accord (1995), Society for Macedonian Studies, Ephesus Publishing, 2007

- Macedonian nationalism

- Macedonian irredentism

- Nationalism in North Macedonia

- Modern history of Greek Macedonia