Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine (Havana)

| Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine, ca. 1930 |

| Architectural style | Classical |

| Address | Malecon and |

| Town or city | |

| Country | Cuba |

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 23°8′42″N 82°22′54″W / 23.14500°N 82.38167°W |

| Groundbreaking | 1925 |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 40 feet |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Load bearing |

| Material | White marble |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Félix Cabarrocas, architect |

| Known for | Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine |

| References | |

| USS Maine | |

The Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine (Spanish: Monumento a las víctimas del Maine) was built in 1925 on the Malecón boulevard at the end of Línea Calle, in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana, Cuba.

History[]

The American battleship Maine exploded in the Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, killing two officers and 250 sailors. Fourteen of the men eventually died, bringing the death toll to a total 266. A board of inquiry concluded that the explosion was caused by a mine placed outside the ship, and the release of the board’s report led many to accuse Spain of sabotaging the ship, this helped to build public support for the Spanish–American War.[a] Later studies published in 1976, reissued in 1995, concluded that the ship was destroyed from the inside.[1][b]

Built in honor of the American sailors who died in the explosion of USS Maine which served as the pretext for the United States to declare war on Spain. The ship had anchored in Havana harbour for three weeks previously at the request of American Consul Fitzhugh Lee.

USS Maine, general characteristics[]

The Maine was 324 feet 4 inches (98.9 m) long overall, with a beam of 57 feet (17.4 m), a maximum draft of 22 feet 6 inches (6.9 m) and a displacement of 6,682 long tons (6,789.2 t).[2] She was divided into 214 watertight compartments.[3] A centerline longitudinal watertight bulkhead separated the engines and a double bottom covered the hull only from the foremast to the aft end of the armored citadel, a distance of 196 feet (59.7 m). She had a metacentric height of 3.45 feet (1.1 m) as designed and was fitted with a ram bow.[4]

Maine's hull was long and narrow, more like a cruiser than that of Texas, which was wide-beamed. Normally, this would have made Maine the faster ship of the two. Maine's weight distribution was ill-balanced, which slowed her considerably. Her main turrets, awkwardly situated on a cut-away gundeck, were nearly awash in bad weather. Because they were mounted toward the ends of the ship, away from its center of gravity, Maine was also prone to greater motion in heavy seas. While she and Texas were both considered seaworthy, the latter's high hull and guns mounted on her main deck made her the drier ship.[5]

The two main gun turrets were sponsoned out over the sides of the ship and echeloned to allow both to fire fore and aft. The practice of en echelon mounting had begun with Italian battleships designed in the 1870s by Benedetto Brin and followed by the British Navy with HMS Inflexible, which was laid down in 1874 but not commissioned until October 1881.[6] This gun arrangement met the design demand for heavy end-on fire in a ship-to-ship encounter, tactics which involved ramming the enemy vessel.[7] The wisdom of this tactic was purely theoretical at the time it was implemented. A drawback of an en echelon layout limited the ability for a ship to fire broadside, a key factor when employed in a line of battle. To allow for at least partial broadside fire, Maine's superstructure was separated into three structures. This technically allowed both turrets to fire across the ship's deck (cross-deck fire), between the sections. This ability was limited as the superstructure restricted each turret's arc of fire.[8]

This plan and profile view show Maine with eight six-pounder guns (one is not seen on the port part of the bridge but that is due to the bridge being cut away in the drawing). Another early published plan shows the same. In both cases the photographs show a single extreme bow mounted six-pounder. Careful examination of Maine photographs confirms that she did not carry that gun. Maine's armament set up in the bow was not identical to the stern which had a single six-pounder mounted at extreme aft of the vessel. Maine carried two six-pounders forward, two on the bridge and three on the stern section, all one level above the abbreviated gun deck that permitted the ten-inch guns to fire across the deck. The six-pounders located in the bow were positioned more forward than the pair mounted aft which necessitated the far aft single six-pounder.

Spanish–American War[]

Maine's destruction did not result in an immediate declaration of war with Spain, but the event created an atmosphere that precluded a peaceful solution.[9] The Spanish investigation found that the explosion had been caused by spontaneous combustion of the coal bunkers, but the Sampson Board ruled that the explosion had been caused by an external explosion from a torpedo.

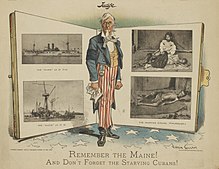

The episode focused national attention on the crisis in Cuba. The McKinley administration did not cite the explosion as a casus belli, but others were already inclined to go to war with Spain over perceived atrocities and loss of control in Cuba.[10]Advocates of war used the rallying cry, "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!"[11][12] The Spanish–American War began on April 21, 1898, two months after the sinking.

American interest in the Caribbean[]

In 1823, the fifth American President James Monroe (1758–1831, served 1817–1825) enunciated the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that the United States would not tolerate further efforts by European governments to retake or expand their colonial holdings in the Americas or to interfere with the newly independent states in the hemisphere; at the same time, the doctrine stated that the U.S. would respect the status of the existing European colonies. Before the American Civil War (1861–1865), Southern interests attempted to have the United States purchase Cuba and convert it into a new slave territory. The pro-slavery element proposed the Ostend Manifesto proposal of 1854. It was rejected by anti-slavery forces.

After the American Civil War and Cuba's Ten Years' War, U.S. businessmen began monopolizing the devalued sugar markets in Cuba. In 1894, 90% of Cuba's total exports went to the United States, which also provided 40% of Cuba's imports.[13] Cuba's total exports to the U.S. were almost twelve times larger than the export to her mother country, Spain.[14] U.S. business interests indicated that while Spain still held political authority over Cuba, economic authority in Cuba, acting-authority, was shifting to the US.

The U.S. became interested in a trans-isthmus canal either in Nicaragua, or in Panama, where the Panama Canal would later be built (1903–1914), and realized the need for naval protection. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was an especially influential theorist; his ideas were much admired by future 26th President Theodore Roosevelt, as the U.S. rapidly built a powerful naval fleet of steel warships in the 1880s and 1890s. Roosevelt served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897–1898 and was an aggressive supporter of an American war with Spain over Cuban interests.

Meanwhile, the "Cuba Libre" movement, led by Cuban intellectual José Martí until his death in 1895, had established offices in Florida.[15] The face of the Cuban revolution in the U.S. was the Cuban "Junta", under the leadership of Tomás Estrada Palma, who in 1902 became Cuba's first president. The Junta dealt with leading newspapers and Washington officials and held fund-raising events across the US. It funded and smuggled weapons. It mounted a large propaganda campaign that generated enormous popular support in the U.S. in favor of the Cubans. Protestant churches and most Democrats were supportive, but business interests called on Washington to negotiate a settlement and avoid war.[16]

Cuba attracted enormous American attention, but almost no discussion involved the other Spanish colonies of the Philippines, Guam, or Puerto Rico.[17][page needed] Historians note that there was no popular demand in the United States for an overseas colonial empire.[18]

USS Maine dispatch to Havana and loss[]

McKinley sent USS Maine to Havana to ensure the safety of American citizens and interests, and to underscore the urgent need for reform. Naval forces were moved in position to attack simultaneously on several fronts if the war was not avoided. As Maine left Florida, a large part of the North Atlantic Squadron was moved to Key West and the Gulf of Mexico. Others were also moved just off the shore of Lisbon, and still others were moved to Hong Kong.[19]

At 9:40 on the evening of February 15, 1898, Maine sank in Havana Harbor after suffering a massive explosion. While McKinley urged patience and did not declare that Spain had caused the explosion, the deaths of 250 out of 355[20] sailors on board focused American attention. McKinley asked Congress to appropriate $50 million for defense, and Congress unanimously obliged. Most American leaders took the position that the cause of the explosion was unknown, but public attention was now riveted on the situation and Spain could not find a diplomatic solution to avoid war. Spain appealed to the European powers, most of whom advised it to accept U.S. conditions for Cuba in order to avoid war.[21] Germany urged a united European stand against the United States but took no action.[22]

The U.S. Navy's investigation, made public on March 28, concluded that the ship's powder magazines were ignited when an external explosion was set off under the ship's hull. This report poured fuel on popular indignation in the US, making the war inevitable.[23] Spain's investigation came to the opposite conclusion: the explosion originated within the ship. Other investigations in later years came to various contradictory conclusions, but had no bearing on the coming of the war. In 1974, Admiral Hyman George Rickover had his staff look at the documents and decided there was an internal explosion. A study commissioned by National Geographic magazine in 1999, using AME computer modelling, stated that the explosion could have been caused by a mine, but no definitive evidence was found.[24]

Sinking[]

In January 1898, Maine was sent from Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba, to protect U.S. interests during the Cuban War of Independence. Three weeks later, at 21:40, on 15 February, an explosion on board Maine occurred in the Havana Harbor (23°08′07″N 082°20′3″W / 23.13528°N 82.33417°W).[25] Later investigations revealed that more than 5 long tons (5.1 t) of powder charges for the vessel's six- and ten-inch guns had detonated, obliterating the forward third of the ship.[26] The remaining wreckage rapidly settled to the bottom of the harbor.

Most of Maine's crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters, in the forward part of the ship, when the explosion occurred. In total, 260[27] men lost their lives as a result of the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries.[27] Captain Sigsbee and most of the officers survived, because their quarters were in the aft portion of the ship. Altogether there were 89 survivors, 18 of whom were officers.[28]

The cause of the accident was immediately debated. Waking up President McKinley to break the news, Commander Francis W. Dickins referred to it as an "accident."[29] Commodore George Dewey, Commander of the Asiatic Squadron, "feared at first that she had been destroyed by the Spanish, which of course meant war, and I was getting ready for it when a later dispatch said it was an accident."[30] Navy Captain Philip R. Alger, an expert on ordnance and explosives, posted a bulletin at the Navy Department the next day saying that the explosion had been caused by a spontaneous fire in the coal bunkers.[31][32] Assistant Navy Secretary Theodore Roosevelt wrote a letter protesting this statement, which he viewed as premature. Roosevelt argued that Alger should not have commented on an ongoing investigation, saying, "Mr. Alger cannot possibly know anything about the accident. All the best men in the Department agree that, whether probable or not, it certainly is possible that the ship was blown up by a mine."[32]

Yellow journalism[]

The New York Journal and New York World, owned respectively by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, gave Maine intense press coverage, employing tactics that would later be labeled "yellow journalism." Both papers exaggerated and distorted any information they could obtain, sometimes even fabricating news when none that fitted their agenda was available. For a week following the sinking, the Journal devoted a daily average of eight and a half pages of news, editorials and pictures to the event. Its editors sent a full team of reporters and artists to Havana, including Frederic Remington,[33] and Hearst announced a reward of $50,000 "for the conviction of the criminals who sent 258 American sailors to their deaths."[34]

The World, while overall not as lurid or shrill in tone as the Journal, nevertheless indulged in similar theatrics, insisting continually that Maine had been bombed or mined. Privately, Pulitzer believed that "nobody outside a lunatic asylum" really believed that Spain sanctioned Maine's destruction. Nevertheless, this did not stop the World from insisting that the only "atonement" Spain could offer the U.S. for the loss of ship and life, was the granting of complete Cuban independence. Nor did it stop the paper from accusing Spain of "treachery, willingness, or laxness" for failing to ensure the safety of Havana Harbor.[35] The American public, already agitated over reported Spanish atrocities in Cuba, was driven to increased hysteria.[36]

Monument[]

Fifteen years after the explosion of the USS Maine in 1913, President of the Cuban Republic Mario García Menocal erected a monument on the Malecón in honor of the victims. The architect Félix Cabarrocas oversaw the construction which began in 1924 and ended in 1925 under the tenure of President Alfredo Zayas. On the day of its inauguration, 8 March 1925, Cuban and American personalities attended the celebration including President Zayas and American General John Pershing.[1] At the base of the monument were placed two canons and a remaining part of the ship’s anchor chain that had been salvaged in 1911. In addition, two 40-foot tall Ionic columns were erected; originally the columns did not hold an eagle. Subsequently, they were crowned with a bronze eagle with open wings, created by Cabarrocas. A bronze plaque reads:“To the Victims of the USS Maine. The people of Cuba”.[37]

The eagle with its wings extended vertically in such a way that a hurricane in October 1926 damaged the monument. The original eagle was replaced in 1926 by one with horizontal wings. The first one is now in the U.S. Embassy in Havana.

President busts[]

There were originally three busts of Americans: President William McKinley, who declared war on Spain; Leonard Wood, first military governor in Cuba, and President Theodore Roosevelt. On July 4, 1943, a fourth bust was added—that of Andrew Summers Rowan, the army officer who was said to have carried a message to General Calixto Garcia just prior to the start of the Spanish-American War.[38]

Partial destruction[]

On 18 January 1961, the eagle and busts of the Americans were removed, because it was considered a "symbol of imperialism," The following inscription was later added:

To the victims of the Maine who were sacrificed by the imperialist voracity and their desire to gain control of the island of Cuba

February 1898 – February 1961

(A las víctimas de El Maine que fueron sacrificadas por la voracidad imperialista en su afán de apoderarse de la isla de Cuba.

Febrero 1898 – Febrero 1961)

"The eagle was torn down after the triumph of the revolution because it's the symbol of imperialism, the United States, and the revolution ended all that," said Ernesto Moreno, a 77-year-old Havana resident who remembers waking up one day and seeing the statue gone. "I found it to be a very good thing, and I think most Cubans agreed at the time."[39]

Monument restoration[]

The eagle's head was later given to Swiss diplomats. It, too, is now in the building of the Embassy of the United States, Havana. The body and the wings are stored in the Havana City History Museum. The museum's curator believes that good relations with the U.S. will be symbolized by the reunification of the parts of the eagle. Parts of the monument including the original eagle are today being restored[39]

Gallery[]

The monument shortly after completion.

The monument today, front view.

The monument today, side view.

False flag conspiracy theory[]

The official view in Cuba is that the sinking was a false flag operation conducted by the U.S. Cuban officials argue that the U.S. deliberately sank the ship to create a pretext for military action against Spain. The Maine monument in Havana describes Maine's sailors as "victims sacrificed to the imperialist greed in its fervor to seize control of Cuba",[40] which claims that U.S. agents deliberately blew up their own ship.[41]

Eliades Acosta was the head of the Cuban Communist Party's Committee on Culture and a former director of the José Martí National Library in Havana. He offered the standard Cuban interpretation in an interview to The New York Times, but he adds that "Americans died for the freedom of Cuba, and that should be recognized."[42] This claim has also been made in Russia by Mikhail Khazin, a Russian economist who once ran the cultural section at Komsomolskaya Pravda.[43]

Operation Northwoods was a series of proposals prepared by Pentagon officials for the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1962, setting out a number of proposed false flag operations that could be blamed on the Cuban Communists in order to rally support against them.[44][45] One of these suggested that a U.S. Navy ship be blown up in Guantanamo Bay deliberately. In an echo of the yellow press headlines of the earlier period, it used the phrase "A 'Remember the Maine' incident".[45][46]

Other USS Maine monuments[]

Other monuments to USS Maine are located in the U.S. including: Central Park in New York City; Wood-Ridge, NJ; Key West; Arlington National Cemetery; and Annapolis. (See USS Maine: Memorials)

See also[]

- Spanish–American War

- USS Maine (1889)

- Barrio de San Lázaro, Havana

- Hotel Nacional de Cuba

Notes[]

- ^ "The Rickover team analyzed the V shape of the keel. Instead of suggesting an external mine, it indicated that the source of the explosion was solely within the ship." RICKOVER, HOW THE BATTLESHIP MAINE WAS DESTROYED, at 114-115.

- ^ "Many ships, including the Maine, had coal bunkers located next to magazines that stored ammunition, gun shells, and gunpowder. Only a bulkhead separated the bunkers from the magazines. If the coal, by spontaneous combustion, overheated, the magazines were at risk of exploding. An investigative board on January 27, 1898, warned the Secretary of the Navy about spontaneous coal fires that could detonate nearby magazines." Allen, Remember the Maine?, at 108.

References[]

- ^ "Destruction of the Maine (1898)" (PDF). The Law Library of Congress. www.loc.gov. August 4, 2009. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Reilly & Scheina, p. 32.

- ^ Morley.

- ^ Reilly & Scheina, pp. 28, 33.

- ^ Cowan & Sumrall, p. 134.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 125, 127.

- ^ Friedman, Battleships, p. 21.

- ^ Reilly & Scheina, p. 24.

- ^ Musicant, pp. 151–2.

- ^ Reilly & Scheina, p. 30.

- ^ Edgerton, Robert B. (2005). Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-6266-3. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Remember the "MAINE"". U.S. Department of Transportation: National Transportation Library. Retrieved 11 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Pérez, Louis A., Jr, Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. p. 149

- ^ Pérez, Louis A., Jr, Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. p. 138

- ^ Gary R. Mormino, "Cuba Libre, Florida, and the Spanish American War", Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal (2010) Vol. 31 Issue 1/2, pp. 43–54

- ^ Auxier, George W. (1939). "The Propaganda Activities of the Cuban Junta in Precipitating the Spanish-American War, 1895-1898". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 19 (3): 286–305. doi:10.2307/2507259. JSTOR 2507259.

- ^ George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: US Foreign Relations Since 1776 (2008)

- ^ Field, James A. (1978). "American Imperialism: The Worst Chapter in Almost Any Book". The American Historical Review. 83 (3): 644–668. doi:10.2307/1861842. JSTOR 1861842.

- ^ Offner 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Thomas, Evan (2010). The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898. Little, Brown and Co. p. 48.

- ^ Keenan, Jerry (2001). Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American & Philippine–American Wars. ABC-CLIO. p. "european+powers" 372. ISBN 978-1-57607-093-2. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 614.

- ^ Offner 2004, p. 57. For a minority view that downplays the role of public opinion and asserts that McKinley feared the Cubans would win their insurgency before the US could intervene, see Louis A. Pérez, "The Meaning of the Maine: Causation and the Historiography of the Spanish–American War", The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 58, No. 3 (August 1989), pp. 293–322.

- ^ For a summary of all the studies see Louis Fisher, "Destruction of the Maine (1898)" (2009) Archived March 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers, p. Plate 1.

- ^ Crawford, Hayes & Sessions 1998.

- ^ NHHC Survivors of USS Maine.

- ^ Dickins, Francis W. (December 8, 1898). "Memorandum to the Secretary of the Navy". Documentary Histories: Spanish-American War. Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ^ Dewey, George (February 18, 1898). "Letter to George Goodwin Dewey". Documentary Histories: Spanish-American War. Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ^ "Destruction of the Maine". Documentary Histories: Spanish-American War. Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roosevelt, Theodore (February 28, 1898). "Letter to Captain Charles O'Neil, Chief of the Ordnance Bureau". Documentary Histories: Spanish-American War. Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ^ Musicant, pp. 143–44.

- ^ Wisan, pp. 390–1. As quoted in Musicant, p. 144.

- ^ Musicant, p. 144.

- ^ Musicant, p. 152.

- ^ "Will the eagle return?". Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Rice, Donald Tunnicliff (2016). Cast in Deathless Bronze: Andrew Rowan, the Spanish-American War, and the Origins of American Empire. West Virginia University Press. pp. 271–2. ISBN 978-1-943665-43-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Havana restores monument to victims of USS Maine". Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Remembering the Maine, CNN, 15 February 1998

- ^ Conner Gorry and David Stanley, "Cuba travel guide", ISBN 978-1-74059-120-1, 3rd edition, 2004, p. 82

- ^ "Havana Journal; Remember the Maine? Cubans See an American Plot Continuing to This Day". Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ^ Mikhail Khazin, "In 3 years, most of our oligarchs will go bankrupt", an interview with Komsomolskaya Pravda, 29 October 2008 (in Russian)

- ^ Ruppe, David (1 May 2001). "U.S. Military Wanted to Provoke War With Cuba". ABC News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weiner, Tim (19 November 1997). "Declassified Papers Show Anti-Castro Ideas Proposed to Kennedy". The New York Times. New York City: NYTC. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Secretariat to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. "Operation Northwoods" (PDF). Washington D.C. p. 8. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

External links[]

- Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine from the Library of Congress at Flickr Commons

- Hartshorn, Byron, "Visiting the USS Maine around Washington, DC"

- United States Navy, Bureau of Steam Engineering, Specifications for triple-expansion twin-screw propelling machinery for U.S.S. Maine at Google Books. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- From spanamwar.com:

- USS Maine Pictures from the Library of Congress American Memory website

- Photo gallery of Maine at NavSource Naval History – Construction – Active Service

- USS Maine from NARA

- Google Books:

- Black, William F. "The Story of the Maine" in Proceedings of the Municipal Engineers of the City of New York

- Monuments and memorials in Cuba

- USS Maine (1889)

- Spanish–American War memorials

- Buildings and structures in Havana

- Tourist attractions in Havana

- 1889 ships

- Armored cruisers of the United States Navy

- Battleships of the United States Navy

- Conspiracy theories in the United States

- Cuba–United States relations

- History of Key West, Florida

- International maritime incidents

- Maritime incidents in 1898

- Ships sunk by non-combat internal explosions

- Ship fires

- Ships built in Brooklyn

- Shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico

- Spanish–American War

- United States Navy Maine-related ships

- Naval magazine explosions

- 1898 fires