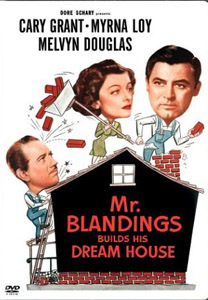

Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House

| Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House | |

|---|---|

DVD cover | |

| Directed by | H. C. Potter |

| Screenplay by | Melvin Frank Norman Panama |

| Based on | Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House by Eric Hodgins Mr. Blandings Builds His Castle 1946 Fortune |

| Produced by | Dore Schary Melvin Frank Norman Panama |

| Starring | Cary Grant Myrna Loy Melvyn Douglas |

| Narrated by | Melvyn Douglas |

| Cinematography | James Wong Howe |

| Edited by | Harry Marker |

| Music by | Leigh Harline |

Production company | RKO Radio Pictures |

| Distributed by | Selznick Releasing Organization |

Release date | March 25, 1948 (New York)[1] June 4, 1948 (US) |

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2,750,000 (US rentals)[2] |

Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House is a 1948 American comedy film directed by H. C. Potter and starring Cary Grant, Myrna Loy, and Melvyn Douglas. The film was written and produced by the team of Melvin Frank and Norman Panama, and was an adaptation of Eric Hodgins' popular 1946 novel, illustrated by Shrek! author William Steig.

This film was the third and last pairing of Grant and Loy, who had shared a comfortable chemistry previously in The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947) and Wings in the Dark (1935).[3]

The film was a box office hit upon its release. Warner Home Video released the film to DVD with restored and remastered audio and video in 2004. The film was remade in 1986 as The Money Pit, starring Tom Hanks and Shelley Long,[4] and in 2007, as Are We Done Yet?, starring Ice Cube.[5]

Plot[]

Jim Blandings, a bright account executive in the advertising business, lives with his wife Muriel and two daughters, Betsy and Joan, in a cramped New York apartment. Muriel secretly plans to knock out a wall and remodel their apartment for $7,000 ($75,400 today). After rejecting this idea, Jim Blandings comes across an ad for new homes in Connecticut and they get excited about moving. Planning to purchase and "fix up" an old home, the couple contact a real estate agent, who uses them to unload "the old Hackett Place" in (fictional) Lansdale County, Connecticut. It is a leaning, dilapidated, nearly 200-year old farmhouse on some 35 acres where General Gates stopped to water his horses during the Revolutionary War. The Blandingses purchase the property for 5 times more than the going rate per acre for locals, provoking his friend/lawyer Bill Cole to chastise him for following his heart rather than his head.

The old house, dating from the Revolutionary War-era, turns out to be structurally unsound and has to be torn down before the previous owner's mortgage is paid off. The Blandings hire architect Henry Simms to design and supervise the construction of the new home for $18,000 ($193,900 today). From the original purchase to the completion of the new home, a long litany of unforeseen troubles and setbacks - including digging a deep well only to find there was a spring only a few feet under the foundation - beset the hapless Blandings and delayed their move-in date. Mrs. Blandings insists on having four bedrooms and four bathrooms. The demolished house's owner also sues them for the balance of his mortgage. On top of all this, at work Jim is assigned the task of coming up with a slogan for "WHAM" Brand Ham, an advertising account that has destroyed the careers of previous account executives assigned to it. Jim also suspects that Muriel is cheating on him after Bill Cole slept alone in the house with Muriel one night due to a violent thunderstorm.

With mounting pressure, skyrocketing expenses, and the encroaching deadline for his assignment, Jim starts to wonder why he wanted to live in the country. Bill observes that although he has been the voice of doom, pointing out all the ways they were being cheated, when he looks at what they have here, he realizes that some things "you do buy with your heart and not your head. Maybe those are the things that really count.” Gussie, a black maid working for the Blandings, provides Jim with the perfect WHAM slogan—"If you ain't eating WHAM, you ain't eating ham"—and saves his job. Gussie is rewarded by the Blandings with a $10 raise ($100 today), and her likeness is used in the WHAM advertising campaign.[6][7] The film ends with the family, with Bill, enjoying the beautiful front yard. Jim, who is reading the book Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, invites the audience to “Drop in and see us some time.”

Cast[]

- Cary Grant as James Blandings

- Myrna Loy as Muriel Blandings

- Melvyn Douglas as William "Bill" Cole

- Louise Beavers as Gussie

- Reginald Denny as Henry Simms

- Jason Robards, Sr. as John Retch

- Connie Marshall as Betsy Blandings

- Sharyn Moffett as Joan Blandings

- Ian Wolfe as Real Estate Agent Smith

- Nestor Paiva as Joe Apollonio

- Lex Barker as Carpenter Foreman

- Harry Shannon as W.D. Tesander

- Tito Vuolo as Mr. Zucca

- Emory Parnell as Mr. PeDelford

Reception[]

According to Time magazine, "Cary Grant, Myrna Loy and Melvyn Douglas have a highly experienced way with this sort of comedy, and director H. C. Potter is so much at home with it that he gets additional laughs out of the predatory rustics and even out of the avid gestures of a steam shovel. Blandings may turn out to be too citified for small-town audiences, and incomprehensible abroad; but among those millions of Americans who have tried to feather a country nest with city greenbacks, it ought to hit the jackpot."[8]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that "as straight entertainment, this ambling and genial report on a young advertising man's disasters (and final triumph) in becoming a country squire is as much casual fun as can be looked for on our sparsely provided screen."[9]

Variety called it "a mildly amusing comedy" with Grant "up to his usual performance standard," but found the script to be flawed when an "unnecessary jealousy twist is introduced, neither advancing the story nor adding laughs."[10]

John McCarten of The New Yorker described the film as "quite ingeniously put together," comparing it to George Washington Slept Here and finding it "just as amiable" as that earlier film.[11]

Harrison's Reports called the film "a first-rate topical comedy farce ... The story itself is a flimsy affair, but it is so rich in witty dialogue and in comedy incidents that one is kept laughing all the time."[12]

While quite popular, according to one source the film actually recorded a loss of $225,000 during its initial theatrical release.[13]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #72[14]

Promotion[]

As a promotion for the film, the studio built 73 "dream houses" in various locations in the United States, selling some of them by raffle;[15] over 60 of the houses were equipped by General Electric, including the ones in the following cities:[16]

Phoenix, AZ, Little Rock, AR, Bakersfield, CA, Fresno, CA, Oakland, CA, Sacramento, CA, San Diego, CA, San Francisco, CA, Denver, CO, Bridgeport, CT, Hartford, CT, Washington, DC, Atlanta, GA, Chicago, IL, Indianapolis, IN, South Bend, IN, Terre Haute, IN, Des Moines, IA, Louisville, KY, Baltimore, MD, Worcester, MA, Detroit, MI, Grand Rapids, MI, St. Paul, MN, Kansas City, MO, St. Louis, MO, Omaha, NE, Tenafly, NJ, Albuquerque, NM, Albany, NY, Buffalo, NY, Rochester, NY, Syracuse, NY, Tarrytown, NY, Utica, NY, Greensboro, NC, Rocky Mount, NC, Cleveland, OH, Columbus, OH, Toledo, OH, Oklahoma City, OK, Tulsa, OK, Cedar Hills, OR (near Portland),[17] Philadelphia, PA, Pittsburgh, PA, Providence, RI, Chattanooga, TN, Memphis, TN, Nashville, TN, Amarillo, TX, Austin, TX, Dallas, TX, Fort Worth, TX, Houston, TX, Salt Lake City, UT, Seattle, WA, and Spokane, WA.

Locations also included Worcester and East Natick, Massachusetts; Portland, Oregon; and Ottawa Hills, Ohio. Thousands lined up in front of the house in Ottawa Hills, paying admission to view the house at its opening.[15]

In Phoenix, the dream house was a ranch house built by P.W. Womack Construction Company in a central city development called BelAir (now part of Encanto Village).[18]

In Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the dream house that was built still stands at 1515 Lafayette Avenue.[19] Greensboro's dream house was built in the Starmount Forest community.[20]

Related works[]

The story behind the film began as an April 1946 article written by Eric Hodgins for Fortune magazine; that article was reprinted in Reader's Digest and (in condensed form[21]) in Life before being published as a novel.[22]

A half-hour radio adaptation of the movie was broadcast on NBC's Screen Directors Playhouse on July 1, 1949.[23] Grant reprised his role as Jim Blandings, and Frances Robinson played his wife Muriel. On October 10, 1949 CBS's Lux Radio Theatre presented a one-hour adaptation of the film,[24] with Irene Dunne taking on the role of Muriel. Screen Directors Playhouse gave a second performance of its half-hour version on June 9, 1950, this time with Grant's wife Betsy Drake playing Muriel.[25]

On January 21, 1951 a weekly radio series starring Cary Grant and Betsy Drake and titled Mr. and Mrs. Blandings premiered on NBC.[26] The comedy series was sponsored by Trans-World Airlines and followed the adventures of the Blandings family after their move into their dream house.

An episode of the 1950s television anthology series Stage 7, titled The Hayfield, aired on September 18, 1955, and was based on the Blandings characters. This episode was a television pilot produced by Four Star Productions for a planned, but ultimately unproduced, weekly series entitled Blandings' Way.[27] Macdonald Carey and Phyllis Thaxter played the Blandings in this version. In the episode, Mr. Blandings attempts to clear a hayfield on his property by burning it off, with the predictably disastrous results.

In the late 1950s Screen Gems Productions also proposed a weekly television series featuring the Blandings family. Robert Rockwell was considered for the show[28] but the television pilot for the planned series featured Steve Dunne instead, along with Maggie Hayes.[29] The show would have been titled The Blandings, but a series was never produced. However the pilot ran on April 27, 1959 as an episode of Goodyear Theatre, under the title A Light in the Fruit Closet.[30]

Buildings[]

The house built for the 1948 film still stands on the old Fox Ranch property in Malibu Creek State Park in the hills a few miles north of Malibu.[citation needed] It is used as an office for the Park.

After seeing the picture at a local theater, in 1950 dentist Luther Werner Fetter and his wife, Mary, purchased the plans for the house from RKO Productions, which produced the film, and built a complete replica of it on Mt. Joy Street in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. The Fetters moved into the house at Christmas in 1950. Mary Fetter continued to live in the home until her death in an automobile accident in 1960, while Dr. Fetter remained the sole occupant of the property until his death in 2002.[31] Coordinates: 34°5′41.4″N 118°42′43.63″W / 34.094833°N 118.7121194°W

In real life, the family of the author, Eric Hodgins, built their house in the Litchfield County town of New Milford, Connecticut. The last recorded sale was in 2004 for $1.2 million.[32]

Similar themes[]

- The Money Pit, 1986 film starring Tom Hanks and Shelley Long.

- Drömkåken, 1993 Swedish film.

- Are We Done Yet? (a sequel to the 2005 film Are We There Yet?) starring Ice Cube, was released on April 4, 2007.

- George Washington Slept Here, 1942 film based on a 1940 play about a couple who refurbish a broken down old house of some possible historical significance.

References[]

- ^ "Selznick-Eyssell Tiff Results In 'Blandings' Shift to N.Y. Astor". Variety: 7. March 10, 1948.

- ^ ""Top Grossers of 1948", Variety 5 January 1949 p 46". Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-07-06. Retrieved 2019-07-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Are We Done Yet? (2007)". New York Times. April 4, 2007. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- ^ Regester, Charlene B. (14 June 2010). African American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility, 1900–1960. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0253221926.

- ^ Palmer, Phyllis (8 August 1991). Domesticity And Dirt: Housewives and Domestic Servants in the United States, 1920-1945. Women In The Political Economy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0877229015.

- ^ "The New Pictures". Time. April 5, 1948. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (March 26, 1948). "The Screen". The New York Times: 26.

- ^ "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House". Variety: 15. March 31, 1948.

- ^ McCarten, John (April 3, 1948). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 58.

- ^ "'Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House' with Cary Grant, Myrna Loy and Melvyn Douglas". Harrison's Reports: 50. March 27, 1948.

- ^ Eyman, Scott (2005). Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer. Robson Books. p. 420. ISBN 9781439107911. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A home made famous in the 1948 mega-hit 'Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House' is in Ottawa Hills". toledoblade.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ "General Electric has made your Dream House come true! (advertisement)". Life. June 28, 1948. p. 78. ISSN 0024-3019. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ The Oregonian (January 17, 2012). "Mr. Blandings' Dream House, 1948". Vintage Portland. vintageportland.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

The Portland-area house was built in the Cedar Hills area of Beaverton... on the northwest corner of SW Walker Road and Mayfield Avenue.

- ^ Susie Steckner (August 2008). "Arizona Dreamin'". Phoenix magazine. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ Nicholas Graham (July 2013). "Mr Blandings Dream House Rocky Mount NC". Digital NC blog. Archived from the original on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ Benjamin Briggs (October 2012). "Secrets of Hamilton Lake". Preservation Greensboro blog. Archived from the original on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ "Mr. Blandings Builds His Castle". Life. April 29, 1946. p. 114ff. ISSN 0024-3019. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ "Mr. Blandings Goes to Hollywood". Life. April 12, 1948. pp. 111–124. ISSN 0024-3019. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ "Radio Programs - TODAY'S BEST BETS (9:00 pm)". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York). 1949-07-01. p. 19. Archived from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ^ "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House". radio adaptation. Lux Radio Theater via the Internet Archive. October 10, 1949. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ "Radio Programs - TODAY'S BEST BETS (9:00 pm)". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York). 1950-06-09. p. 27. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ^ Bundy, Jane (1951-02-03). "Television-Radio Reviews: Mr. and Mrs. Blandings". The Billboard. p. 8. Retrieved 2016-06-18.

- ^ "Expansion at Four Star; to Add 3 Shows". The Billboard. 1955-05-14. p. 6. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ Hyatt, Wesley (2003). "The Man from Blackhawk". Short-Lived Television Series, 1948-1978: Thirty Years of More Than 1,000 Flops. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 102. ISBN 0-7864-1420-0. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ Goldberg, Lee (2015). "Screen Gems Production #403". Unsold Television Pilots: 1955-1989. Adventures in Television, Inc. ISBN 978-1511590679. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ "Desilu Resumes with Smashup Of Capone Empire". The Pittsburgh Press. 1959-04-27. p. 37. Retrieved 2021-08-26.

- ^ Reed, Lloyd (April 8, 2014). "1950 House Inspired by "Mr. Blandings"". The Elizabethtown Journal. The Elizabethtown Journal. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018.

- ^ "The Blandings House in Conn. Inspires the Ultimate Movie Premiere". New England Historical Society. 2018-02-21. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

External links[]

- Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House at IMDb

- Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House at AllMovie

- Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House at the TCM Movie Database

- Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House at Rotten Tomatoes

- http://www.robertabalos.com/2012/01/mr-blandings-builds-his-dream-house.html

- English-language films

- 1948 films

- 1948 comedy films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- American comedy films

- Films about advertising

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by H. C. Potter

- Films scored by Leigh Harline

- Films set in Connecticut

- Films set in New York City

- RKO Pictures films