Nansō Satomi Hakkenden

Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (shinjitai: 南総里見八犬伝; kyūjitai: 南總里見八犬傳) is a Japanese epic novel (yomihon) in 106 volumes by Kyokutei Bakin. The volumes were written and published over a period of nearly thirty years (1814–42). Bakin had gone blind before finishing the tale, and he dictated the final parts to his daughter-in-law Michi. The title has been translated as The Eight Dog Chronicles,[1] Tale of Eight Dogs,[2] or Biographies of Eight Dogs.[3]

Plot and influences[]

Nansō Satomi Hakkenden is a fantasy novel about eight youngsters (The Eight Dog Warriors) bound by a fateful connection in another world between Princess Fuse, a princess of the Satomi clan in Awa, and the dog of kami Yatsufusa, set in the late Muromachi period (350 years before Bakin lived). The eight Dog Warriors, who commonly have family names including the character for '犬' (Inu, dog) each have a peony shaped bruise somewhere on their body and a bead of Japamala with the characters for humanity, justice, courtesy, wisdom, loyalty, sincerity, filial piety and obedience. Born in various parts of the eight provinces of Kanto region, they get to know each other guided by the fate of each other while experiencing hardship, and gather together under the Satomi clan. They served the Satomi clan and fought against the allied forces of powerful feudal lords, and the story came to an end. The themes of their adventures are loyalty, clan honor, Bushido, Confucianism, and Buddhist philosophy.[4]

Bakin borrowed the idea from the Chinese novel Water Margin which was translated and published in Japan at the beginning of the 18th century,[5] and wrote epic fantasies by referring to the historical stories of the Satomi and Hojo clans.[4]

A complete reprinting in ten volumes is available in the original Japanese, as well as various modern Japanese translations, most of them abridged. Only a few chapters had been translated into English, Chapter 25 by Donald Keene,[2] Chapters 12, 13, and 19 by Chris Drake,[3] and in 2021 the first volume of a translation by Glynne Walley, titled Eight Dogs, or "Hakkenden" Part One - An Ill-Considered Jest was published by Cornell University Press.[6]

History of reception[]

Since Hakkenden was very popular among ordinary people at that time, ukiyo-e with various characters were also sold. Kabuki plays based on Hakkenden were often performed, and ukiyo-e depicting kabuki actors playing the roles of eight warriors were also popular.

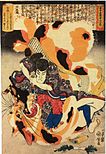

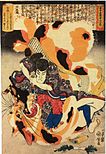

Inukawa Sōsuke. The One and Only Eight Dog History of Old Kyokutei, Best Refined authors. by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Inumura Daikaku. The One and Only Eight Dog History of Old Kyokutei, Best Refined authors. by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Princess Fuse saving Inue Shimbyoe Masahi from a thunderbolt. by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Inudzuka Shino on Hōryūkaku roof looking down on Inukai Kenpachi with geese flying below full moon. by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Actor Nakamura Tamasuke I (Nakamura Utaemon III) as Moriguchi Kurō, a Valiant Retainer of Satomi Yūshin. by Utagawa Kunisada II

Hugely popular at the time of publication and into the early twentieth century, Bakin's work lost favor after the Meiji Restoration, but came back into fashion later in the twentieth century.

In live-action film and TV there have been numerous adaptions: the first in 1913, then a series in the 1950s, and since the influential TV series Shin Hakkenden (ja:新八犬伝) from the early 1970s, every decade has had either a live-action adaptation or a show significantly influenced by the novel, right up through the 2010s.

The novel has also been adapted into kabuki theatre several times.[7] In August 2006, the Kabuki-za put on the play.[8] In 1959, the TOEI motion picture company made Satomi hakken-den.[9] In 1983, the novel was loosely adapted into the film Legend of the Eight Samurai.

Hakkenden has had a strong influence on modern manga and anime works, particularly those based on adventure quests. For example, it influenced Akira Toriyama's Dragon Ball (1984) and Rumiko Takahashi's Inuyasha (1996), which both have plots about the collection of magical crystals or crystal balls.[10]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Shirane, Haruo (2002). Early Modern Japanese Literature: an Anthology, 1600-1900. Columbia University Press. p. 886. ISBN 0-231-10990-3.

- ^ Rimer, J. Thomas (2007). The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature: From Restoration to Occupation, 1868-1945. Coughlan Publishing. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-231-11861-3.

- ^ Keene, Donald (1955). Anthology of Japanese Literature, From the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Grove Press. p. 423. ISBN 0-8021-5058-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kotobanlk, Nansō Satomi Hakkenden. The Asahi Shimbun

- ^ Shirane and Brandon, Early Modern Japanese Literature, p564.

- ^ "Product Details". Cornell University Press. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ "Nansô Satomi Hakkenden". kabuki21.com. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Satomi hakken-den at IMDb

- ^ Papp, Zília (2010). Anime and Its Roots in Early Japanese Monster Art. Global Oriental. p. 38. ISBN 978-90-04-20287-0.

Works cited[]

- ^ Kyokutei Bakin (1819) "Shino and Hamaji". In Keene, Donald (Ed.) ([1955] 1960) Anthology of Japanese Literature: from the earliest era to the mid-nineteenth century, pp. 423–428. New York, NY: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-5058-6

- ^ Kyokutei Bakin (1819) "Fusehime at Toyama Cave," "Fusehime's Decision," "Shino in Otsuka Village," "Hamaji and Shino". Translated by Chris Drake in Haruo Shirane (Ed.) (2002) Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology 1600–1900, pp. 885–909. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10991-1

Further reading[]

- (1983). "Nansō Satomi Hakkenden". Nihon Koten Bungaku Daijiten 日本古典文学大辞典 (in Japanese). 4. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. pp. 571–573. OCLC 11917421.

- Keene, Donald (1999) [1993]. A History of Japanese Literature, Vol. 2: World Within Walls – Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1600–1867 (paperback ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11467-7.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nansō Satomi Hakkenden. |

- Original text of Nansō Satomi Hakkenden, first 30 chapters as of 2006 (Japanese)

- The Hakkenden Hakuryu-Tei website and the complete Japanese version

- ^ The Legend of the Eight Samurai Hounds, English translation in progress since September 2015

- 19th-century Japanese novels

- Edo-period works

- Japanese novels adapted into plays

- Japanese serial novels

- Japanese novels adapted into films