National Autonomous University of Mexico

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México | |

Official seal of the University, designed by rector José Vasconcelos | |

| Latin: Universitas Nationalis Autonoma Mexici | |

Former name | Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico |

|---|---|

| Motto | Por mi raza hablará el espíritu |

Motto in English | "Through my race, the spirit shall speak" |

| Type | Public university |

| Established | Originally established on 21 September 1551, Reopened on 22 September 1910[1][2][3][4][5][6] |

| Endowment | US$2.4 billion (2012)[7] |

| Rector | Enrique Graue Wiechers |

Academic staff | 41,318 (As of 2019)[8] |

| Students | 356,530 (2011–2018 academic year)[8] |

| Undergraduates | 213,004 (As of 2018)[8] |

| Postgraduates | 30,089 (As of 2018)[8] |

| Location | Mexico City , Mexico 19°19′44″N 99°11′14″W / 19.32889°N 99.18722°WCoordinates: 19°19′44″N 99°11′14″W / 19.32889°N 99.18722°W |

| Campus | Urban, 7.3 km2 (2.8 sq mi), main campus only |

| Colors | Blue and gold |

| Athletics | 41 varsity teams[9] |

| Mascot | Puma |

| Website | english |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Central University City Campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 2007 (31st session) |

| Reference no. | 1250 |

| State Party | Mexico |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

The National Autonomous University of Mexico (Spanish: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, lit. 'Autonomous National University of Mexico', UNAM) is a public research university in Mexico. It ranks highly in world rankings based on the university's extensive research and innovation.[10][11][12] It is the largest university in Latin America[13] and has one of the biggest campuses in the world.[14] UNAM's main campus in Mexico City, known as Ciudad Universitaria (University City), is a UNESCO World Heritage site that was designed by some of Mexico's best-known architects of the 20th century. Murals in the main campus were painted by some of the most recognized artists in Mexican history, such as Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. In 2016, it had an acceptance rate of only 8%.[15] UNAM generates a number of strong research publications and patents in diverse areas, such as robotics, computer science, mathematics, physics, human-computer interaction, history, philosophy, among others. All Mexican Nobel laureates are either alumni or faculty of UNAM.

UNAM was founded, in its modern form, on 22 September 1910 by Justo Sierra[1][2][3][4] as a liberal alternative to its predecessor, the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, the first in North America, founded in 1551.[16] UNAM obtained its autonomy from the government in 1929. This has given the university the freedom to define its own curriculum and manage its own budget without government interference. This has had a profound effect on academic life at the university, which some claim boosts academic freedom and independence.[17]

UNAM was the birthplace of the student movement of 1968.[18]

History[]

Its founding goes back to 1551, when Carlos I, King of Spain (Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire) decreed the foundation of the University of Mexico.[19] The university was renamed on 22 September 1910 by Justo Sierra,[1][2][3][4] then Minister of Education in the Porfirio Díaz regime, who sought to create a very different institution from its 19th-century precursor, the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, which had been founded on 21 September 1551 by a royal decree signed by Crown Prince Phillip on behalf of Charles I of Spain[20] and brought to a definitive closure in 1865 by Maximilian I of Mexico.[21][22] Instead of reviving what he saw as an anachronistic institution with strong ties to the Roman Catholic Church,[23] he aimed to merge and expand Mexico City's decentralized colleges of higher education (including former faculties of the old university) and create a new university, secular in nature and national in scope, that could reorganize higher education within the country, serve as a model of positivism and encompass the ideas of the dominant Mexican liberalism.[2]

The project initially unified the Fine Arts, Business, Political Science, Jurisprudence, Engineering, Medicine, Normal, and the National Preparatory schools;[24] its first rector was .[25]

The new university's challenges were mostly political, due to the ongoing Mexican Revolution and the fact that the federal government had direct control over the university's policies and curriculum; some resisted its establishment on philosophical grounds. This opposition led to disruptions in the function of the university when political instability forced resignations in the government, including that of President Díaz. Internally, the first student strike occurred in 1912 to protest examination methods introduced by the director of the School of Jurisprudence, Luis Cabrera. By July of that year, a majority of the law students decided to abandon the university and join the newly created Free School of Law.[25]

In 1914 initial efforts to gain autonomy for the university failed.[25] In 1920, José Vasconcelos became rector. In 1921, he created the school's coat-of-arms: the image of an eagle and a condor surrounding a map of Latin America, from Mexico's northern border to Tierra del Fuego, and the motto, "The Spirit shall speak for my people". Efforts to gain autonomy for the university continued in the early 1920s. In the mid-1920s, the second wave of student strikes opposed a new grading system. The strikes included major classroom walkouts in the law school and confrontation with police at the medical school. The striking students were supported by many professors and subsequent negotiations eventually led to autonomy for the university. The institution was no longer a dependency of the Secretariat of Public Education; the university rector became the final authority, eliminating much of the confusing overlap in authority.[26]

During the early 1930s, the rector of UNAM was Manuel Gómez Morín. The government attempted to implement socialist education at Mexican universities, which Gómez Morín, many professors, and Catholics opposed as an infringement on academic freedom. Gómez Morín with the support of the Jesuit-founded student group, the Unión Nacional de Estudiantes Católicos, successfully fought against socialist education. UNAM supported the recognition of the academic certificates by Catholic preparatory schools, which validated their educational function. In an interesting turn of events, UNAM played an important role in the founding of the Jesuit institution in 1943, the Universidad Iberoamericana in 1943.[27] However, UNAM opposed initiatives at the Universidad Iberoamericana in later years, opposing the establishment of majors in industrial relations and communications.[28]

In 1943 initial decisions were made to move the university from the various buildings it occupied in the city center to a new and consolidated university campus; the new Ciudad Universitaria (lit. University City) would be in San Ángel, to the south of the city.[29] The first stone laid was that of the faculty of Sciences, the first building of Ciudad Universitaria. President Miguel Alemán Valdés participated in the ceremony on 20 November 1952. The University Olympic Stadium was inaugurated on the same day. In 1957 the Doctorate Council was created to regulate and organize graduate studies.[30]

Another major student strike, again over examination regulations, occurred in 1966. Students invaded the rectorate and forced the rector to resign. The Board of Regents did not accept this resignation, so the professors went on strike, paralyzing the university and forcing the Board's acceptance. In the summer, violent outbreaks occurred on a number of the campuses of the university's affiliated preparatory schools; police took over several high school campuses, with injuries.

Students at UNAM, along with other Mexico City universities, mobilized in what has come to be called Mexico 68, protests against the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, but also a whole array of political and social tensions. During August 1968, protests formed on the main campus against the police actions on the main campus and in the center of the city. The protests grew into a student movement that demanded the resignation of the police chief, among other things. More protests followed in September, gaining frequency and numbers. During a meeting of the student leaders, the army fired on the Chihuahua building in Tlatelolco, where the student organization supposedly was. In the Tlatelolco massacre, the police action resulted in many dead, wounded, and detained. Protests continued on after that. Only ten days later, the 1968 Olympic Games opened at the University Stadium. The university was shut down for the duration.[31]

The 1970s and 1980s saw the opening of satellite campuses in other parts of Mexico and nearby areas, to decentralize the system. There were some minor student strikes, mostly concerning grading and tuition.[32][33]

The last major student strike at the university occurred in 1999–2000 when students shut down the campus for almost a year to protest a proposal to charge students the equivalent of US$150 per semester for those who could afford it. Referendums were held by both the university and the strikers, but neither side accepted the others' results. Acting on a judge's order, the police stormed the buildings held by strikers on 7 February 2000, putting an end to the strike.[34][35][36]

In 2009 the university was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities[37] and began the celebration of its centennial anniversary with several activities that will last until 2011.[38]

The UNAM has actively included minorities into different educational fields, as in technology.[39][40][41][42] In 2016, the university adopted United Nations platforms throughout all of its campuses to support and empower women.[43][44][45]

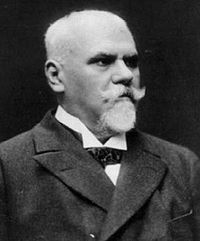

Seal[]

José Vasconcelos, as rector in 1920, expressed the importance of ending the oppression and the bloody confrontations of yesteryear, the battlefields would be those of culture and education would be a means to achieve a new era in the country where Mexicans have in mind the need to merge peoples and culture from the spiritual factors, race and territory, reflecting the unification of Latin Americans. These elements were reflected in the University Seal, represented by the Mexican eagle and the Andean condor, forming a double-headed eagle, supported by an allegory of the volcanoes and a cactus, meaning of the roots of the Mexicans. In the central part of the shield is the map of Latin America, which goes from the northern border of Mexico to Cape Horn. Framing this map is the phrase "For my people the spirit shall speak." In the upper part of the seal there is a ribbon that says "National Autonomous University of Mexico".

Motto[]

The motto that animates the National University, "For my people the spirit shall speak", reveals the humanistic vocation with which it was conceived. The author of this famous phrase, José Vasconcelos, assumed the rectory in 1920, within the framework of the Latin American University Reform, and at a time when the hopes of the Mexican Revolution were still alive; There was a great faith in the homeland, and the redemptive spirit extended into the environment. It "means in this motto the conviction that our race will elaborate a culture of new tendencies, of spiritual and free essence," explained the "Master of America" when presenting the proposal. Later, he would specify: "I imagined the university shield that I presented to the Council, roughly and with a legend: 'For my people the spirit shall speak', pretending to mean that we woke up from a long night of oppression" [46]

Imagotype[]

On April 20, 1974, the then rector Guillermo Soberón Acevedo presented the new sport's emblem of the UNAM in the Auditorium of the Faculty of Sciences. The university commissioned the design to Manuel Andrade Rodríguez, as part of the renovation of the General Directorate of Sports and Recreation Activities. The image was chosen among 16 works, and required more than 800 sketches.[47]

The image type consists of the face of a puma in gold, made from the silhouette of a closed fist, on a blue triangle with rounded corners. In turn, this triangle expresses the three fundamental pillars of the University: Education, Research and the Diffusion of Culture.

The emblem of the puma serves as a seal for the sports teams of the university. In 2013, it was considered by the British newspaper The Guardian one of the most beautiful in football.[48]

Campuses[]

University City[]

"Ciudad Universitaria" (University City) is UNAM's main campus, located within the Coyoacán borough in the southern part of Mexico City. The construction of UNAM's central campus was the original idea of two students from the National School of Architecture in 1928: Mauricio De Maria y Campos[49] and Marcial Gutiérrez Camarena. It was designed by architects Mario Pani, Armando Franco Rovira, Enrique del Moral, Eugenio Peschard, Ernesto Gómez Gallardo Argüelles, Domingo García Ramos, and others such as Mauricio De Maria y Campos who always showed great interest in participating in the project. Architects De Maria y Campos, Del Moral, and Pani were given the responsibility as directors and coordinators to assign each architect to each selected building or constructions which enclose the Estadio Olímpico Universitario, about 40 schools and institutes, the Cultural Center, an ecological reserve, the Central Library, and a few museums. It was built during the 1950s on an ancient solidified lava bed to replace the scattered buildings in downtown Mexico City, where classes were given. It was completed in 1954, and is almost a separate region within Mexico City, with its own regulations, councils, and police (to some extent), in a more fundamental way than most universities around the world.

In June 2007, its main campus, Ciudad Universitaria, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[50]

Satellite campuses[]

Apart from University City (Ciudad Universitaria), UNAM has several campuses in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City (Acatlán, Aragón, Cuautitlán, Iztacala, and Zaragoza), as well as many others in several locations across Mexico (in Santiago de Querétaro, Morelia, Mérida, Sisal, Ensenada, Cuernavaca, Temixco and Leon), mainly aimed at research and graduate studies. Its School of Music, formerly the National School of Music, is located in Coyoacán. Its Center of Teaching for Foreigners has a campus in Taxco, in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, focusing in Spanish language and Mexican culture for foreigners, as well as locations in the upscale neighborhood of [Polanco] in central Mexico City.[51][52][53]

The University has extension schools in the United States, and Canada, focusing on the Spanish language, English language, Mexican culture, and, in the case of UNAM Canada, French language: UNAM San Antonio, Texas; UNAM Los Angeles, California; UNAM Chicago, Illinois; Gatineau, Quebec; and Seattle, Washington.[54]

It operates Centers for Mexican Studies and/or Centers of Teaching for Foreigners in Beijing, China (jointly with the Beijing Foreign Studies University); Madrid, Spain (jointly with the Cervantes Institute); San Jose, Costa Rica (jointly with the University of Costa Rica); London, United Kingdom (with King's College London);[55] Paris, France (jointly with Paris-Sorbonne University); and Northridge, California, United States (jointly with California State University Northridge).

Museums and buildings of interest[]

Palacio de Minería[]

Under the care of the School of Engineering, UNAM, the Colonial Palace of Mining is located in the historical center of Mexico City. Formerly the School of Engineering, it has three floors, and hosts the International Book Expo ("Feria Internacional del Libro" or "FIL") and the International Day of Computing Security Congress ("DISC"). It also has a permanent exhibition of historical books, mostly topographical and naturalist works of 19th-century Mexican scientists, in the former library of the School of Engineers. It also contains several exhibitions related to mining, the prime engineering occupation during the Spanish colonization. It is considered to be one of the most significant examples of Mexican architecture of its period, conceived by Manuel Tolsa during de Spanish colonial rule in a neoclassical style (18th century).

Casa del Lago[]

The House of the Lake, in Chapultepec Park, is a place devoted to cultural activities, including dancing, theater, and ballet. It also serves as a meeting place for university-related organizations and committees.

Museum of San Ildefonso[]

This museum and cultural center is considered to be the birthplace of the Mexican muralism movement.[56][57] San Ildefonso began as a prestigious Jesuit boarding school, and after the Reform War, it gained educational prestige again as National Preparatory School, which was closely linked to the founding of UNAM. This school, and the building, closed completely in 1978, then reopened as a museum and cultural center in 1994, administered jointly by UNAM, the National Council for Culture and Arts and the government of the Federal District of Mexico City. The museum has permanent and temporary art and archaeological exhibitions, in addition to the many murals painted on its walls by José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera and others.[58][59] The complex is located between San Ildefonso Street and Justo Sierra Street in the historic center of Mexico City.[56]

Chopo University Museum[]

The Chopo University Museum possesses an artistic architecture, large crystal panels and two iron towers designed by Gustave Eiffel. It opened with part of the collection of the now-defunct Public Museum of Natural History, Archeology and History, which eventually became the National Museum of Cultures.[60] It served the National Museum of Natural History for almost 50 years, and is now devoted to the temporary exhibitions of visual arts.

Museo Experimental El Eco[]

The Museo Experimental El Eco is one of the two buildings by German modern artist Mathias Goeritz and an example of Emotional architecture. Goeritz was a close collaborator of architect Luis Barragán and author of several public sculptures including the Torres de Satélite. The building was acquired and renovated by the National University in 2004 and since 2005 it exhibits contemporary art and a yearly architecture competition Pabellón Eco.

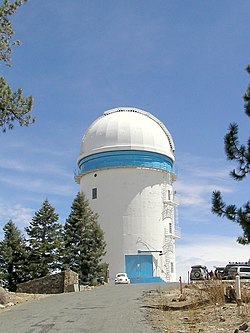

National Astronomical Observatory[]

The National Astronomical Observatory is located in the Sierra San Pedro Mártir mountain range in Baja California, about 130 km south of United States-Mexican border. It has been in operation since 1970, and it currently has three large reflecting telescopes.

Academics[]

The acceptance rate of this university was 5.9% in 2013 and 8% in 2016.

Nobel laureates[]

All three of Mexico's Nobel laureates are alumni of UNAM:

- Alfonso García Robles (alumnus) - Nobel Peace Prize, 1982

- Octavio Paz (alumnus) - Nobel Prize in Literature, 1990

- Mario Molina (alumnus) - Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1995

Noted faculty[]

- See also Category:National Autonomous University of Mexico faculty

- Carlos Slim, businessman and the current fourth-richest person in the world[61]

- Miguel Alcubierre, theoretical physicist

- Max Cetto, architect

- Mónica Clapp, mathematician

- Adolfo Gilly, historian

- Alejandro Corichi, astrophysicist

- Enrique Leff, political ecologist and economist

- Laura Hernández Guzmán, psychologist

- Isabel Hubard Escalera, mathematician

- Erich Fromm, philosopher and psychoanalyst

- Florian Luca, mathematician

- Teodoro González de León, architect

- Javier Corral Jurado, politician

- Jorge González Torres, politician

- José Gaos, philosopher

- José Miguel Insulza, a Chilean politician, secretary of the Organization of American States

- Paul Kirchhoff, anthropologist and ethnohistorian

- Larry Laudan, philosopher

- , musician (guitar)

- Miguel León-Portilla, historian and Nahuatl language researcher

- Rodolfo Neri Vela, astronaut

- Edmundo O'Gorman, historian and writer

- Kiyoto Ota, sculptor

- Arturo Rosenblueth, physiologist

- Graciela Salicrup (1935–1982), architect, archaeologist and mathematician

- , psychologist[62]

- Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez, a Spanish-born philosopher

- Manuel Sandoval Vallarta, physicist and cosmic ray researcher

- Sara Sefchovich, writer

- , robotics researcher and founder of the Mexican Institute of Robotics

- Bernardo Sepúlveda Amor, lawyer[62]

Noted alumni[]

- See also Category:National Autonomous University of Mexico alumni

World heads of state[]

- Abel Pacheco (President of Costa Rica 2002–2006)

- Alfonso Portillo (President of Guatemala 2000–2004)

- Carlos Salinas de Gortari (President of Mexico 1988–1994)

- José López Portillo y Pacheco (President of Mexico 1976–1982)

- Luis Echeverría (President of Mexico 1970–1976)

- Miguel Alemán Valdés (President of Mexico 1946–1952)

- Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado (President of Mexico 1982–1988)

- Andrés Manuel López Obrador (Mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2005, President of Mexico 2018–present[63])

Politicians[]

- Abel Pacheco (President of Costa Rica)

- Alan Cranston (U.S. Senator from California) - one summer

- Alfonso Portillo (President of Guatemala)

- Álvaro García Linera (Vice-President of Bolivia)

- Alejandro Encinas (Mayor of Mexico City)

- Antonio Carrillo Flores (Cabinet Minister in several previous administrations, 1929, 1950[64])

- Carlos Mendoza Davis (Governor of Baja California Sur)

- Claudia Sheinbaum (scientist, politician, and Mayor of Mexico City)

- Fernando Baeza Melendez (Senator and Governor of Chihuahua)

- Luis Félix López (Secretary of Government of Ecuador)

- Manlio Fabio Beltrones Rivera (Deputy, Senator and Governor of Sonora)

- Miguel Ángel Mancera (Mayor of Mexico City)

- Mark Kirk (U.S. Senator from Illinois, did not graduate[65])

- Rosario Robles (Mexican politician who served as the Secretary of Social Development)

- Santiago Creel (senator)

- Veton Surroi (Kosovo publicist and leader of the Kosovar Party ORA)

Diplomats[]

- Antonio Carrillo Flores (Ministry of Mexican Foreign Affairs during the Díaz Ordaz administration)

- Jaime Torres Bodet (writer and politician, UNESCO Director-General (1948-1952))

- Narciso Bassols (former ambassador to Russia, France, and Great Britain; former director of UNAM's School of Law)

- Marco Antonio Garcia Blanco (Ambassador of Mexico to Nigeria)

- Rosario Green (Ministry of Mexican Foreign Affairs during the Zedillo administration)

Artists, writers, and humanists[]

- Abraham Cruzvillegas (artist)

- Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez (philosopher and writer)

- Agustín Landa Verdugo (architect and urban planner)

- Alejandro Rossi (philosopher and writer)

- Alfonso Cuarón (film director, winner of the Academy Award for Best Director in 2014)

- Alfonso García Robles (diplomat and Treaty of Tlatelolco impeller, Nobel Prize laureate in Peace)

- Alfonso Reyes (writer, philosopher, and diplomat)

- Ana Colchero (actress)

- Adelina Nicholls (activist)

- Audre Lorde (writer, poet and activist)

- Emiliano Monge

- Ayako Tsuru (mural artist)

- Bolívar Echeverría (Ecuadorian writer and philosopher)

- Carlos Fuentes (writer, essayist, and a member of El Colegio Nacional)

- Carlos Monsiváis (editorialist and writer)

- Carmen Aristegui (journalist)

- Chespirito (screenwriter, creator of the sitcoms El Chavo del Ocho and El Chapulín Colorado)

- Elena Poniatowska (journalist and writer)

- Fernando del Paso (writer)

- Francisco Laguna Correa (writer)

- (political writer)

- Horst Matthai Quelle (philosopher)

- Jacobo Zabludovsky (lawyer, journalist, and first TV anchorman in Mexico)

- Jacqueline Peschard (sociologist)

- Jaime Maussan (Mexican journalist, television personality and ufologist)

- Javier Solorzano (journalist)

- Jorge Volpi (novelist and essayist; current director of Canal 22 in Mexican free television)

- José Emilio Pacheco (writer and a member of El Colegio Nacional)

- Josefina Muriel (writer, historian, researcher, bibliophile, academic; Order of Isabella the Catholic by the government of Spain in 1966)

- Juan García Esquivel (musician)

- Juan Rulfo (writer)

- Julio Estrada (composer, writer, and UNAM scholar)

- Julio Scherer García (author, journalist and founder of Proceso news magazine. He was the editor of the daily newspaper Excélsior but was sacked because President Luis Echeverría pursuing)

- Ilse Gradwohl (painter)

- Maruxa Vilalta (dramatist)

- Octavio Paz (poet and essayist; Nobel laureate in Literature)

- (sociologist)

- Pola Weiss Álvarez (video artist)

- Ricardo Legorreta (laureated architect)

- Rosa Beltrán (writer, lecturer and academic)

- Rosario Castellanos (writer, philosopher, poet, feminist and diplomat)

- Salvador Elizondo (writer and a member of the Colegio Nacional)

- Subcomandante Marcos (aka - "Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente" - sociologist, philosopher and Zapatista Army of National Liberation founder)

- Teodoro González de León (architect)

- Veronica Castro (movie star)

- William F. Buckley (writer and political philosopher; attended in 1943 prior to being commissioned in the U.S. Army during the World War II)

Physicians and surgeons[]

- (specialist in pancreatic diseases, , gastrointestinal surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, USA)[66]

- Fernando Antonio Bermúdez Arias (prominent physician, cardiologist, scientist, writer, teacher, historian, artist, and social defender)

- Ignacio Chávez (prominent Mexican physician, founded the first cardiology area in the General Hospital of Mexico. He was the rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (1965–1966). Founded several Mexican institutions in Cardiology and he was appointed honorary doctor or rector of 95 universities around the world. He was a founding member of El Colegio Nacional (1943).)

- Jorge Calles-Escandón (endocrinologist, specializing in , type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and insulin pumps at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, USA)

- Gerardo Jiménez Sánchez (pediatrician, founding president of the Mexican Society of Genomic Medicine)

- Mauricio Tohen, Distinguished Professor, and Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at the University of New Mexico

- Nora Volkow (director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse)

Scientists[]

- Alfonso Caso y Andrade (archaeologist)

- Antonio Lazcano (biologist and evolutionist, director of )

- Carlos Frenk (astronomer, a pioneer in simulations of large-scale structures)

- Constantino Reyes-Valerio (chemist and historian who coined the term arte indocristiano and contributed to the discovery of the production of Maya blue pigment)

- Eduardo Pareyón Moreno (archaeologist)

- Guido Münch (astronomer and director of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy)

- Guillermo Haro (astronomer, co-discoverer of Herbig–Haro object

- Guillermo Oliver (biologist and professor at Northwestern University

- Jerzy Rzedowski (plant scientist, pioneer in the field of neotropical floristics)

- Juan J. de Pablo (chemical engineer and vice president for national laboratories, science strategy, innovation, and global initiatives at the University of Chicago)

- Luis E. Miramontes (co-inventor of the contraceptive pill)

- Marcos Moshinsky (theoretical physicist, whose work in the field of elementary particles won him the Prince of Asturias Prize for Scientific and Technical Investigation in 1988 and the UNESCO Science Prize in 1997)

- Mario Molina (co-discoverer of decomposition of ozone with CFC aerosols, Nobel laureate in Chemistry)

- Miguel Alcubierre (theoretical and computational physicist; see Alcubierre metric)

- Miguel de Icaza (free software programmer)

- Monica Olvera de la Cruz (soft matter theorist)

- Nabor Carrillo Flores (a soil mechanics expert, a nuclear energy advisor and former president of UNAM)

- Rodolfo Neri Vela (the first Mexican in space)

- Salvador Zubirán (physician, founder of the National Institute of Nutrition)

- Shlomo Eckstein (economist and President of Bar-Ilan University)

- Víctor Neumann-Lara (pioneer in graph theory in Mexico)

- Ricardo Miledi (neuroscientist, worked on the calcium hypothesis of neurotransmitter release)

Business people[]

- Carlos Slim (Engineering businessman and the current fourth richest person in the world)[61]

Athletes[]

- Hugo Sánchez (Mexican football player, Real Madrid C.F., former Mexico national team and UD Almería manager)

- Daniel Vargas (Mexican volleyball player and engineer, played for Pumas UNAM, and was part of Mexico men's national volleyball team, where he played at the Olympic Games Rio 2016)

- (Mexican volleyball player and coach, head coach of the male volleyball team at Pumas UNAM, and manager of Mexico men's national volleyball team, where he directed the first Mexican team to make it to the Olympic Games for indoor volleyball)

Organization[]

UNAM is organized in schools or colleges, rather than departments. Both undergraduate and graduate studies are available. UNAM is also responsible for the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (ENP) (National Preparatory School), and the (CCH) (Science and Humanities College), which consist of several high schools, in Mexico City. Counting ENEP, CCH, FES (Facultad de Estudios Superiores), higher-secondary, undergraduate and graduate students, UNAM has over 324,413 students, making it one of the world's largest universities.[8]

Schools and colleges[]

UNAM has a set of schools covering different academic fields such as "engineering" or "law". All of UNAM's schools offer undergraduate and graduate studies (master's degrees and PhDs). However, the schools that UNAM calls "national schools" only offer undergraduate studies, as this type of school is mainly focused on practical experience. This is the case of the , and the .[68]

List of schools, and institutes[]

- Schools (all of these offer undergraduate and graduate degrees)

- School of Accounting and Administration

- School of Architecture

- School of Chemistry

- School of Economics

- School of Engineering

- School of Medicine

- School of Philosophy and Letters

- School of Political and Social Sciences

- School of Sciences

- National Schools (only have undergraduate degrees)

- National Preparatory School (with 9 high schools)

- National School of High Studies Morelia (in the state of Michoacan)

- National School of High Studies León (in the state of Guanajuato)

- National School of High Studies Mérida (in the state of Yucatan)

- National School of High Studies Juriquilla (in the state of Queretaro)

- National School 'College of Sciences and Humanities' (with 5 high schools)

Open University and Distance Education System[]

The Open University and Distance Education System or "Sistema de Universidad Abierta y Educación a Distancia" (SUAyED) is an alternative to the university's on-campus education. The open education programs require on-campus assistance at least one in every 15 days, usually on Saturdays (semi-presence). The distance education programs are entirely online using content provided through online platforms where students, teachers, and peers communicate online. About 32,000 of UNAM's students are enrolled in open or distance programs.[69]

SUAyED offers bachelor and postgraduate degrees.

Research[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2021) |

UNAM has excelled in many areas of research. The university houses many of Mexico's premiere research institutions. In recent years, it has attracted students and hired professional scientists from all over the world, most notably from Russia, India, and the United States, creating a unique and diverse scientific community.

Scientific research at UNAM is divided between faculties, institutes, centers, and schools, and covers a range of disciplines in Latin America. Some notable UNAM institutes include the Institute of Astronomy, the Institute of Biotechnology, the Institute of Nuclear Sciences, the Institute of Ecology, the Institute of Physics, Institute of Renewable Energies, the Institute of Cell Physiology, the Institute of Geophysics, the Institute of Engineering, the Institute of Materials Research, the Institute of Chemistry, the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, and the Applied Mathematics and Systems Research Institute.

Research centers tend to focus on multidisciplinary problems particularly relevant to Mexico and the developing world, most notably, the Center for Applied Sciences and Technological Development, which focuses on connecting the sciences to real-world problems (e.g., optics, nanosciences), and Center for Energy Research, which conducts world-class research in alternative energies.

All research centers are open to students from around the world. The UNAM holds a number of programs for students within the country, using scientific internships to encourage research in the country.

UNAM currently installed its first supercomputer Sirio (Cray Y/MP) in 1991. Since 2013 it operates a supercomputer named Miztli (HP) for scientific research.

Students and faculty[]

Sports, clubs, and traditions[]

Professional football club[]

UNAM's football club, Club Universidad Nacional, participates in Liga MX, the top division of Mexican football. The club became two-time consecutive champions of the , and the in 2004. Their home ground is the Estadio Olímpico Universitario.

Pumas volleyball team[]

UNAM's volleyball team, Pumas, has had great success on a national and international level.[70] The manager for Mexico's representative volleyball team is from Pumas, and several players representing Mexico are also UNAM students and alumni. They played in the Olympics at Rio.

Cultural traditions[]

The university has an annual tradition to make a large display of Day of the Dead offerings (Spanish: ofrenda) all over the main square of Ciudad Universitaria. Each school builds an offering, and in the center, there is usually a large offering made according to a theme corresponding to the festivities of the university for that year.[71]

Political activism[]

UNAM students and professors are regarded throughout Mexico as politically aware and politically active. While most of its students usually adhere to left-wing political ideologies and movements, the university has also borne several prominent right-wing and neoliberal politicians, such as Carlos Salinas de Gortari and Manuel Gómez Morín.

UNAM's history has made it a strong advocate of minorities, especially women in tech. The school of engineering has organized along with Google some of the largest all Latina Hackathons.[39] UNAM along with Google has organized large scale Latina Hackathons.[40]

Student associations[]

The UNAM contains several associations of current students and alumni that provide extra-curricular activities to the whole community, enriching the university's activities with cultural, social, and scientific events.

- Nibiru Sociedad Astronomica

- SAFIR

See also[]

- XHUNAM-TV ("Teveunam", UNAM's educational and cultural television channel)

- DGSCA (Dirección General de Servicios de Cómputo Académico, Hub of Computer Sciences/Engineering in UNAM)

- Mexican Law Review

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. "UNAM Through Time". Archived from the original on 2013-04-06.

Later, on April 26, [1910] he set the National University's founding project in motion. The new institution would be composed of the National Preparatory High School and the School of Higher Studies, along with the schools of Jurisprudence, Medicine, Engineering and Arts (including Architecture). The project was approved and the National University of Mexico was solemnly inaugurated on September 22. The universities of Salamanca, Turkey and Berkeley were its 'godmothers'.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Justo Sierra (1910-09-22). "Discurso en el acto de la inauguración de la Universidad Nacional de México, el 22 de septiembre de 1910" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-03.

¿Tenemos una historia? No. La Universidad mexicana que nace hoy no tiene árbol genealógico

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Annick Lempérière. "Los dos centenarios de la Independencia mexicana (1910–1921): de la historia patria a la antropología cultural" (PDF) (in Spanish). University of Paris I. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-03.

La universidad soñada por Justo Sierra, ministro de Instrucción Pública, última creación duradera del régimen porfirista, se inauguró al mismo tiempo que la Escuela Nacional de Altos Estudios, que debía ceder su lugar a las humanidades, junto a los programas científicos de los cursos porfiristas. El discurso inaugural de Sierra iba a tono con el espíritu de las celebraciones. La universidad naciente no tenía nada en común, insistía, con la que la precedió: no tenía 'antecesores', sino 'precursores'.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Javier Garciadiego. "De Justo Sierra a Vasconcelos. La Universidad Nacional durante la Revolución Mexicana" (PDF) (in Spanish). El Colegio de México. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-17.

El mayor esfuerzo en la vida de Sierra fue, precisamente, revertir tal postura; así, se afanó obsesivamente en crear una universidad de ese tipo, pues era la institución que mejor encabezaba "los esfuerzos colectivos de la sociedad moderna para emanciparse integralmente del espíritu viejo". Al margen de numerosas diferencias sustanciales con los liberales, los positivistas, que dominaron el sistema nacional de instrucción pública superior desde 1865, también eran contrarios al establecimiento de una universidad, tanto por conveniencias políticas como por principios doctrinales. Esto hace más admirable el esfuerzo de don Justo, pues era un miembro destacado —canonizado, dice O'Gorman— del grupo de positivistas mexicanos. Su lucha no fue sólo pedagógica sino también política. Si bien no se puede coincidir con [Edmundo] O'Gorman respecto al carácter de Sierra como jerarca del positivismo mexicano, pues siempre fue cuestionado por los más ortodoxos como un pensador ecléctico, falto de disciplina, es de compartirse la admiración que profesa a don Justo, pues su lucha por la fundación de la Universidad Nacional implicó serios distanciamientos de sus principales compañeros políticos e intelectuales, ya fueran liberales o positivistas.

- ^ Manuel López de la Parra. "La casi centenaria UNAM" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2009-02-01.

"Ciertamente no ha transcendido el hecho de que la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; autónoma desde 1929, está próxima a cumplir su primer centenario de vida académica, pues fue inaugurada el 22 de septiembre de 1910, en ocasión de los festejos del primer centenario del inicio de la Revolución de Independencia durante los últimos tiempos del Gobierno de don Porfirio Díaz, y con base en un proyecto elaborado por don Justo Sierra, por entonces, secretario de Instrucción Pública y Bellas Artes con la participación técnica de don Ezequiel A. Chávez, de acuerdo con el modelo típico de las universidades europeas, precisamente con mucho de la Universidad de París; por ese entonces la influencia europea estaba presente, y en especial, la cultura francesa.

- ^ Marissa Rivera. "Arrancan festejos por los 100 años de la UNAM" (in Spanish).

El rector José Narro anuncia el programa de actividades para conmemorar los 100 años de UNAM, que iniciaron este miércoles y concluirán el 22 de septiembre de 2011.

- ^ UNAM. "Portal de Estadística Universitaria". Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "La UNAM en numeros". Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ "Dirección General de Actividades Deportivas y Recreativas - Inicio". Deportes.unam.mx. Archived from the original on 2013-07-30. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ "QS Latin American University Rankings 2018". 12 October 2017.

- ^ Strauss, Karsten. "The Top 10 Universities In Latin America In 2017". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ "The UNAM is among the best universities in the world". El Universal (in Spanish). 2019-06-19. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ Hollander, Kurt (2008-01-27). "A Campus Serves as a Needed Oasis in a Crowded City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ "Largest Universities In The World". Ranker. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ "Acepta UNAM sólo a 8%, lo más compartido". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM)". Top Universities. 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ Elizalde, Guadalupe, Piedras en el Camino de la UNAM, EDAMEX, 1999 p.49.

- ^ "University Officials Yield to Student Strike in Mexico". archive.nytimes.com.

- ^ "General Direction of International Affairs - UNAM, Mexico \ History". 2014-08-14. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ^ Méndez Arceo, Sergio (1990). La Real y Pontificia Universidad de México: antecedentes, tramitación y despacho de las reales cédulas de erección (in Spanish). Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. pp. 93–100. ISBN 968-36-1704-2. OCLC 25290441.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 10, Appleton, p. 260, ISBN 9780595392414

- ^ Charles A. Hale (2014), The Transformation of Liberalism in Late Nineteenth-Century Mexico, Princeton University Press, p. 193, ISBN 9781400863228

- ^ Justo Sierra. "Discurso en el acto de la inauguración de la Universidad Nacional de México, el 22 de septiembre de 1910" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-03.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1960". Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "UNAM through time – 1910". Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1920". Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ David Espinosa, Jesuit Student Groups, the Universidad Iberoamericana, and Political Resistance in Mexico, 1913-1979. Albuquerque: the University of New Mexico Press 2014, p. 11.

- ^ Espinosa, Jesuit Student Groups, p. 96-97.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1940". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1950". Archived from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1960". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1970". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "UNAM through time – 1980". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Preston, Julia (1999)University Officials Yield to Student Strike in Mexico June 8. Retrieved on February 14, 2006. New York Times.

- ^ Preston, Julia (2000) Big Majority Votes to End Strike at Mexican University January 21, 2000. Retrieved on February 14, 2006 New York Times.

- ^ Mexican Police Storm University February 7, 2000. Retrieved on February 14, 2006, from BBC.

- ^ "The National Autonomous University of Mexico, Prince of Asturias Award Laureate for Communication and Humanities". Oviedo: Prince of Asturias Foundation. 2009-06-10. Archived from the original on 2011-08-25. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ^ "UNAM celebra desde ahora su centenario" [UNAM now celebrates its centennial]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. 2009-10-16. Archived from the original on 2009-10-20. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ser ingeniera en los tiempos de Agustín Lara". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Milenio.com "’Hackatón’ une a mujeres para crear casas inteligentes."[1] in Spanish. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "Primer Hackathon #FixIT UNAM México / Coordinación de Comunicación". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "Latina hackathon FixIT a great success - UCSB Computer Science". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "La UNAM respalda la igualdad de género con 'He for She'". 30 August 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "UNAM se adhiere al programa He For She de la ONU". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2016-09-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Acerca de la UNAM". 2008-05-24. Archived from the original on 2008-05-24. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ "Cumple 40 años el escudo de los Pumas de la UNAM". Excélsior (in Spanish). 2014-04-20. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ Ashdown, John (2013-12-13). "The Joy of Six: weird and wonderful football club crests | John Ashdown". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- ^ "Creación de Ciudad Universitaria". www.comitedeanalisis.unam.mx. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2007-06-29). "UNESCO". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ "Difusion de la cultura oferta cultural". www.unam.mx. Archived from the original on 2009-11-21.

- ^ "Research-Academic-Units". unam.mx. Archived from the original on 2009-11-22.

- ^ "Academic Units". www.unam.mx. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23.

- ^ "The UNAM in the United States - Permanent Extension School (Escuela Permanente de Extensión-EPE-), San Antonio, Texas". www.100.unam.mx. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22.

- ^ "UNAM abre sedes en Alemania y Reino Unido".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Galindo, Carmen; Magdelena Galindo (2002). Mexico City Historic Center. Mexico City: Ediciones Nueva Guia. pp. 86–91. ISBN 968-5437-29-7.

- ^ Horz de Via (ed), Elena (1991). Guia Oficial Centro de la Ciudad d Mexico. Mexico City: INAH-SALVAT. pp. 46–50. ISBN 968-32-0540-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "San Ildefonso en el tiempo". Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ Bueno de Ariztegui (ed), Patricia (1984). Guia Turistica de Mexico Distrito Federal Centro 3. Mexico City: Promexa. pp. 80–84. ISBN 968-34-0319-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Museo Nacional de las Culturas, En la Ciudad de Mexico, Una Ventana al Mundo" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2009-04-08. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "#1 Carlos Slim Helu & family". Forbes. 2010-03-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nota "Nombra la UNAM a Bernardo Sepúlveda, Investigador Extraordinario, y a Juan José Sánchez Sosa, Profesor Emérito. Boletín DGCS-738 October 25, 2016, 11:00 h. (Retrieved October 25, 2016)

- ^ "Elecciones en México". Retrieved May 13, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Colegio Nacional". Colegio Nacional. Archived from the original on 2014-03-09. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ "About Mark Kirk". United States Senate. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-12-18. Retrieved 2008-03-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Carlos Frenk". royalsociety.org.

- ^ "Unidades Académicas". Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "Characterizing UNAM's Open Education System Using the OOFAT Model". IRRODL.org. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Daniel Vargas Goes to the Olympics". Retrieved 12 October 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Noticias - En Día de Muertos en la UNAM imposed récord; decent de cables del DF teen numbers abusive a La Catrina". Cronica.com.mx. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

Bibliography[]

- Jiménez Rueda, Julio. Historia Jurídica de la Universidad de México. Mexico City: Imprenta Universitaria 1955.

- Mabry, Donald J. The Mexican University and the State. College Station: Texas A&M Press 1982.

- Mayo, Sebastián, La educación socialista en México: El Asalto a la Universidad Nacional. Mexico: El Caballito 1985.

- Wences Reza, Rosalío, La Universidad en la historia de México. Mexico: Editorial Línea 1984.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Autonomous University of Mexico. |

- UNAM | Portal UNAM Official website] |(English version): [2]

- UNAM León Campus

- National Autonomous University of Mexico

- National universities

- Public universities and colleges in Mexico

- Schools in Mexico City

- Educational institutions established in 1910

- 1910 establishments in Mexico

- Universities in Mexico City