University of the Philippines Los Baños

Unibersidad ng Pilipinas Los Baños | |

| |

| Motto | Honor and Excellence[1] |

|---|---|

| Type | National, research University |

| Established | 6 March 1909 (112 years and 244 days) |

| Chancellor | Jose V. Camacho Jr. |

| President | Danilo L. Concepcion |

Academic staff | 964[2] |

| Students | 12,027 (2019)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 8,796 (2019)[3] |

| Postgraduates | 2,494 (2019)[3] |

Other students | 737 basic education (2019)[3] |

| Location | , Laguna , Philippines 14°9′54.18″N 121°14′29.55″E / 14.1650500°N 121.2415417°ECoordinates: 14°9′54.18″N 121°14′29.55″E / 14.1650500°N 121.2415417°E |

| Campus | Rural, 15,205 ha (37,570 acres)[4] |

| Hymn | "U.P. Naming Mahal" ("U.P. Beloved") |

| Colors | |

| Affiliations | Association of Pacific Rim Universities ASEAN-European University Network ASEAN University Network |

| Website | https://uplb.edu.ph/main/ |

The University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB; Filipino: Unibersidad ng Pilipinas Los Baños), also referred to as UP Los Baños or colloquially as Elbi (pronounced ['ɛlbi]), is a public research university primarily located in the towns of Los Baños and Bay in the province of Laguna, some 65 kilometers southeast of Manila. It traces its roots to the UP College of Agriculture (UPCA), which was founded in 1909 by the American colonial government to promote agricultural education and research in the Philippines. American botanist Edwin Copeland served as its first dean. UPLB was formally established in 1972 following the union of UPCA with four other Los Baños and Diliman-based University of the Philippines (UP) units.

The university has played an influential role in Asian agriculture and biotechnology due to its pioneering efforts in plant breeding and bioengineering, particularly in the development of high-yielding and pest-resistant crops. In recognition of its work, it was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award for International Understanding in 1977. Six of its research units are classified as Centers of Excellence in Research via Presidential decree,[5] and it hosts a number of local and international research centers, including the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), ASEAN Center for Biodiversity, World Agroforestry Centre, and the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA).

UPLB offers more than 100 degree programs in various disciplines through its nine colleges and two schools. As of 2021, nine academic programs were recognized by the Commission on Higher Education as Centers of Excellence while one program was recognized as Center of Development.[6]

UPLB alumni have been recognized in a wide range of fields. They include 16 scientists awarded the title National Scientist of the Philippines,[2] members of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,[7] Palanca Award winners,[8][9] as well as political and business leaders.

History[]

UPLB was originally established as the University of the Philippines College of Agriculture (UPCA) on 6 March 1909 by the UP Board of Regents. Edwin Copeland, an American botanist and Thomasite from the Philippine Normal College in Manila, was its first dean.[10][11] Classes began in June 1909 with five professors while 12 students initially enrolled in the program.[12]

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, UPCA was closed and the campus converted into an internment camp for allied nationals and a headquarters of the Japanese army.[10] For three years, the college was home to more than 2,000 civilians, mostly Americans, that were captured by the Japanese. In 1945, as part of the liberation of the Philippines, the US Army sent 130 11th Airborne Division paratroopers to Los Baños to rescue the internees.[13] Only four paratroopers and two Filipino guerrillas were killed in the raid. However, Japanese reinforcements arrived two days later, destroying UPCA facilities[10][12] and killing some 1,500 Filipino civilians in Los Baños soon afterwards.[14][15]

UPCA became the first unit of the University of the Philippines to open after the war, with Leopoldo Uichanco as dean. However, only 125 (16 percent) of the original students enrolled. It was even worse for the School of Forestry, which only had nine students. Likewise, only 38 professors returned to teach. UPCA used its ₱470,546 (US$10,800)[16] share in the Philippine-US War Damage Funds (released in 1947) for reconstruction.[17]

Further financial endowments from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Mutual Security Agency (MSA) allowed the construction of new facilities, while scholarship grants, mainly from the Rockefeller Foundation and the International Cooperation Administration, helped fund training of UPCA faculty. From 1947 to 1958, a total of 146 faculty members had been granted MS and PhD scholarships in US universities.[17]

Dioscoro Umali became UPCA dean in 1959. Umali's administration oversaw the creation of IRRI, SEARCA (of which he was the first director),[19] and the Department of Food Science and Technology. New facilities were also constructed under his Five-Year Development Program.[18]

In 1972, UPCA requested Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos to allow the college to secede from the University of the Philippines due to the alleged withholding of its budget and the disapproval of curricular proposals.[19] However, UP President Salvador P. Lopez strongly opposed the idea. A survey found that there was very little support for complete independence at UPCA. As a compromise, Lopez proposed the transformation of UP into a system of autonomous constituent universities. Finally, on 20 November 1972, Presidential Decree No. 58 was signed, establishing UPLB as UP's first autonomous campus, with UPCA, College of Forestry, Agricultural Credit and Cooperatives Institute, Dairy Training and Research Institute, and the Diliman-based Agrarian Reform Institute as its first academic units.[19][10][12][20] New colleges and research centers were created over the next few years, while the College of Veterinary Medicine was likewise transferred to UPLB from UP Diliman.[10]

Campus[]

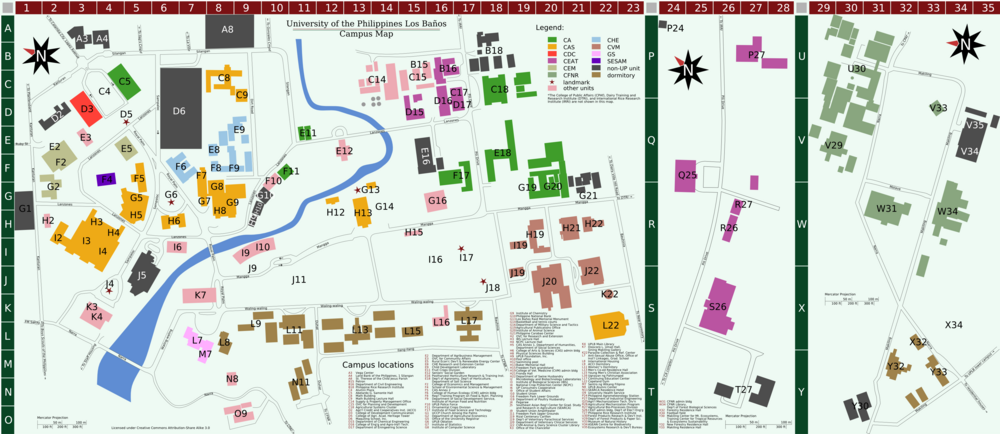

The UPLB campus consists of 14,665 ha (36,240 acres) spread across the provinces of Laguna, Negros Occidental,[21] and Quezon.

Los Baños campus[]

The 1,098 ha (2,710-acre) Los Baños campus houses UPLB's academic facilities, as well as experimental farms for agriculture and biotechnology research.[4] The more prominent buildings in the Los Baños campus, such as the Dioscoro L. Umali Hall, Main Library, and Student Union were designed by National Artist for Architecture Leandro Locsin.[22] Other notable landmarks include the iconic Oblation, Alumni Plaza, Freedom Park, and Baker Memorial Hall.

UPLB is designated as caretaker of the 4,347 ha (10,740-acre)[4] Makiling Forest Reserve (often referred to as the "upper campus," in contrast to the "lower campus" set at the foot of Makiling). It houses facilities of the College of Forestry and Natural Resources, College of Public Affairs, UPLB Museum of Natural History and the University Health Service, among others. The reserve is home to diverse flora and fauna, and has more tree species than the continental United States (an area 32 times bigger than the Philippines).[23] It serves as an outdoor laboratory for faculty and students of the university.[11][24]

Land grants[]

UPLB has three major land grants: the Laguna-Quezon Land Grant, La Carlota Land Grant, and Laguna Land Grant.[4]

The 5,719 ha (14,130-acre) Laguna-Quezon Land Grant is located in the towns of Real, Quezon, and Siniloan, Laguna, and was acquired in February 1930. It covers some portions of the Sierra Madre mountain range, and currently hosts the university's Citronella and lemongrass plantations.[25][26] The 705 ha (1,740-acre) La Carlota Land Grant is situated in Negros Occidental, a province in the Western Visayas region. Acquired in May 1964, it houses the PCARRD-DOST La Granja Agricultural Research Center, which serves as a research center for various upland crops.[4][21][27] Meanwhile, the 3,336 ha (8,240-acre)[4] Laguna Land Grant located in Paete, Laguna, also acquired in 1964, is mostly undeveloped. Numerous parties have expressed interest in developing the land grants; however, UPLB has not entertained the potential investors due to the "lack of a solid development plan."[28]

Panabo Professional School[]

The UP Professional School for Agriculture and the Environment (UP PSAE) in Panabo City was established in 2016 to cater to agribusiness professionals in the Davao metropolitan area. Supervised by the UPLB Graduate School, UP PSAE was established through a grant by Damosa Land Inc., a leading property developer in Mindanao.[29][30]

Organization and administration[]

| University of the Philippines Los Baños Chancellors | |

|---|---|

| Name | Tenure of office |

| Abelardo G. Samonte | 1973–1978 |

| Emil Q. Javier | 1979–1985 |

| Raul P. De Guzman | 1986–1991 |

| Ruben B. Aspiras | 1991–1993 |

| Ruben L. Villareal | 1993–1999 |

| Wilfredo P. David | 1999–2005 |

| Luis Rey I. Velasco | 2005–2011 |

| Rex Victor O. Cruz | 2011–2014 |

| Fernando C. Sanchez Jr. | 2014–2020 |

| Jose V. Camacho, Jr. | 2020– |

| References | [19][31][32][33][34] |

As part of the University of the Philippines System, UPLB is governed by the 11-person UP Board of Regents, which is jointly chaired by the head of the Commission on Higher Education and the UP president.[35][36]

The Board of Regents has the authority to approve the institution, merger, and abolition of degree programs as recommended by the UP president. It also has the power to confer degrees. The UP president, who is appointed by the Board of Regents, is the university's chief executive officer and the head of the faculty.[36]

UPLB is administered by a chancellor who is elected by the UP Board of Regents to a three-year term. The chancellor may only serve for up to two terms.[33][36] Under him are five vice-chancellors specializing in administration, community affairs, instruction, planning and development, and research and extension.[37]

The current chancellor is Dr Jose Camacho, the tenth to hold the office.

UPLB, through the UP System, is a member of the Association of Pacific Rim Universities, a consortium of leading research universities in the Asia-Pacific region.[38]

Student government[]

The University Student Council (USC) is the "highest governing body of all UPLB students." Together with college student councils (CSCs), it assembles as the Student Legislative Chamber and acts as the highest policy-making body of the USC. The USC is composed of a chairperson, vice-chairperson, 10 councilors, a representative for each college/school with less than 500 students, and an additional college representative for every 500 students in excess of the first 500. Members are given one-year terms. CSCs have a similar structure, but with a different number of councilors based on the student population.[39][40]

The Student Disciplinary Tribunal (SDT) is responsible for sanctioning erring students. Common offenses include student misconduct and fraternity rumbles. The SDT is composed of a chairperson, two appointees of the chancellor, a student juror, and a parent juror.[39]

Academics[]

| Unit | Foundation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| College of Agriculture and Food Science | 1909 | [10] |

| College of Arts and Sciences | 1972 | [41] |

| College of Development Communication | 1954 | [42] |

| College of Economics and Management | 1975 | [43] |

| College of Engineering and Agro-Industrial Technology | 1912 | [44] |

| School of Environmental Science and Management | 1977 | [45] |

| College of Forestry and Natural Resources | 1910 | |

| Graduate School | 1972 | [46] |

| College of Human Ecology | 1974 | [47] |

| College of Public Affairs and Development | 1998 | [48] |

| College of Veterinary Medicine | 1908 | [49] |

UPLB offers undergraduate and graduate degree programs through its nine colleges and two schools.[50] Most of these programs award science degrees. It also awards high school diplomas through the University of the Philippines Rural High School (UPRHS), a subunit of the College of Arts and Sciences, which acts as a laboratory for its BS Math and Science Teaching students.[51]

Admission and graduation[]

UPLB admits more than 2,500 students and produces about 1,800 graduates every year. Undergraduate admission is determined by the University of the Philippines College Admission Test (UPCAT). Examinees that select UPLB as their preferred campus and garner a University Predicted Grade (UPG) within the standard cut-off are automatically eligible for admission. Those who do not automatically qualify may file an appeal for reconsideration if their UPG is within the actual cut-off, though the appeal process does not guarantee admission.[52][53] The cut-off scores may be adjusted according to a variety of factors. In 2010 and 2011, UPLB had a standard UPG cut-off of 2.42 while the actual cut-off was 2.8. But in 2014 and 2015, UPLB had a standard cut off score of 2.3.[54][55] Seventy percent of slots are given to incoming freshmen with the highest scores, while the remaining thirty percent are given to public high school students and members of minority groups.[55] Before the UPCAT was used for admission, UPCA only admitted the top 5 percent of Philippine high school graduates.[56]

High school freshman admission, on the other hand, is determined by the eight-hour-long UPRHS Entrance Examination. Only the top 125 examinees are admitted.[57] Sophomore transferees take the two-day UPRHS Validation Examination, and are admitted depending on the available slots.[58]

Normally, a student who completes the program may graduate with honors if his general weighted average (GWA) is 1.75 or above. The title summa cum laude is awarded to graduates who obtain a GWA of 1.20 or above, magna cum laude to graduates with a GWA of 1.45 to 1.20, and cum laude to graduates with a GWA of between 1.75 and 1.45.[59] As of 2011 there have been 30 summa cum laudes who have graduated from UPLB.[60]

Tuition and financial aid[]

The base tuition fee per unit in UPLB is ₱1,000 (US$23).[16] As with all UP constituents, UPLB implements the Socialized Tuition and Financial Assistance Program (STFAP). Under the program, students with annual family incomes between ₱1,000,000 (US$23,000) and ₱500,000 (US$11,500)[16] are charged the base tuition fee, while those with annual family incomes above ₱1,000,000 are charged ₱1,500 (US$35) per unit.[16] Students with annual family incomes between ₱500,000 and ₱135,000 (US$3,110) are charged ₱600 (US$14) per unit;[16] those who have between ₱135,000 and ₱80,000 (US$1,840) are charged ₱300 (US$7);[16] while those who have below ₱80,000 are not charged any fees.[61] Additional financial assistance may be accessed through the Student Loan Board, which pays up to 80 percent of the tuition.[62] Scholarship and loan programs are also offered by some UPLB units, such as the College of Veterinary Medicine.[63]

These rates were introduced in 2007. Previously, base tuition was only ₱300 per unit (since 1989).[61] Library and miscellaneous fees were also increased in 2007, from ₱400 (US$9) per student to ₱1,100 (US$25) and ₱2,000 (US$46), respectively.[16] New fees, such as internet and energy fees, were introduced. The USC at the time saw the over 300 percent increase in tuition as the reason for the low enrollment rate and high student loan levels, which totaled some ₱14 million (US$326,000)[16] in 2007. Additionally, it criticized the STFAP for allegedly being ineffective. Upon its introduction in 1989, only 16 percent of students received discounts. The number fell to 12 percent in 2007.[62]

With the passage of Republic Act 10931, tuition and fees have been waived for students pursuing their degrees for the first time in exchange for return service, although it is possible to opt out and pay the full tuition instead.[64]

Accreditation[]

UPLB is identified by the Commission on Higher Education as a Center of Excellence in Agriculture, Agricultural Engineering, Biology, Forestry, Information Technology, Environmental Science, Development Communication, Statistics and Veterinary Medicine, as well as a Center of Development in Chemical Engineering.[2] Five undergraduate programs were given the ASEAN University Network-Quality Assessment certification: BS Biology, BS Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, BS Development Communication, BS Forestry and BS Agriculture.[65]

Libraries and collections[]

As of 2007, UPLB's 12 libraries, collectively referred to as the University Library, hold a total of 346,061 volumes.[4] It periodically receives publications from United Nations agencies (including the UNFAO, UN-HABITAT and UNU) and the World Bank. It is a contributor to the International Information System for Agricultural Services and Technology, contributing nearly 30,000 titles between 1975 and 2010.[66][67]

195,282 of these volumes are housed at the Main Library, while the rest are in unit libraries. The Main Library also houses theses, digital sources, and 1,215 serial titles, among other materials.[4] It has a total floor area of 6,336 m2 (68,200 sq ft) and a seating capacity of 510, making it the largest library in UPLB.[67]

One of UPLB's unit libraries is the College of Veterinary Medicine-Animal and Dairy Sciences Cluster Library. It has 17,798 volumes and 198 serial titles, and a total floor area of 609.25 m2 (6,557.9 sq ft). It claims to hold the largest collection on veterinary and animal sciences in the country.[68]

UPLB manages the UPLB Museum of Natural History, which was established in 1976 at the foothills of Mt. Makiling. It holds over 600,000 biological specimens, including half of the specimens from the Philippine Water Bug Inventory Project, and a third of the Dioscoro S. Rabor Wildlife Collection. More than half of the specimens belong to the entomological collection. While most of its collections are in its main building, some are housed in other UPLB units.[69]

Research[]

Six research institutes were named Centers of Excellence in Research via Presidential decree: Institute of Plant Breeding, Institute of Food Science and Technology, Institute of Animal Science, National Crop Protection Center, Farming Systems and Soil Resources Institute, and National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology.[5]

UPLB hosts a number of international research institutes, including the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture,[70] the ASEAN Center for Biodiversity,[71] the International Rice Research Institute,[72] the World Fish Center,[73] the World Agroforestry Center,[74] and the Asia Rice Foundation.[75] The APEC Center for Technology Exchange and Training for Small and Medium Enterprises (ACTETSME), established in 1996 through the initiative of then President Fidel V. Ramos during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders' Meeting in Seattle, USA, is also located at the university's Science & Technology Park.[76] Local research institutions such as the Department of Environment and Natural Resources' Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau,[77] Department of Science and Technology's Forest Products Research and Development Institute,[78] and Department of Agriculture's Philippine Carabao Center[79] are headquartered or have offices at the university.[80] The main office of IRRI's Philippine counterpart, the Philippine Rice Research Institute, used to be located at UPLB but was transferred to Muñoz, Nueva Ecija in 1990. It continues to maintain a research office at the university.[81]

Three UPLB-published journals, the Philippine Agricultural Scientist, the Philippine Journal of Veterinary Medicine, and the Journal of Environmental Sciences and Management are listed in the SCImago Journal Rankings. SCImago gave these an h-index (a measure of "actual scientific productivity" and "apparent scientific impact")[82] of 13, 4 and 8, respectively.[83] These journals are also listed in the ISI Web of Knowledge, along with two other UPLB-published journals: the Philippine Entomologist and the Philippine Journal of Crop Science.[84]

Biotechnology research[]

UPLB operates a 155 ha (380-acre) science and technology park. As of February 2010, the park has hosted four companies engaged in biotechnology. The park serves as a location for the commercialization and application of UP technologies.[85]

One of the earliest innovations of UPLB was the production of CAC 87 sugar cane in 1919. This high-yielding variety is resistant to fiji and mosaic viruses, and produces more sucrose than other varieties. Its derivatives significantly increased sugar cane production in the Philippines.[11] Between 1921 and 1939, cattle, poultry, and swine breeding programs produced new breeds, namely the Philamin (a hybrid of the Hereford, Nellore and native cattle), Berkjala (a variety of the Berkshire and local Jala-Jala pig, resistant to hog cholera) and the Los Baños Cantonese chicken, which produces more eggs.[86]

Research in the 1960s allowed for the efficient mass production of macapuno (a type of coconut with jelly-like meat),[87] while studies started in 1998 that produced delayed-ripening papaya continue to this day.[88] The research is credited for the increase in Philippine papaya production, with the 75,896-metric-ton (83,661-short-ton) production of 2000 rising to 164,100 metric tons (180,900 short tons) in 2007.[89] In 1974, UPLB researchers discovered mango flower induction by potassium nitrate, making it possible for the fruit to be available year round. It is credited for tripling yield and for "revolutionizing" the country's mango industry.[90]

In 2009, UPLB researchers funded by the Department of Agriculture developed an abacá variety that is resistant to the abaca bunchy top virus. The virus, first detected in 1915 at Silang, Cavite, has since spread to various provinces in the country, and damaged more than 8,000 ha (20,000 acres) of abacá plantations in 2002 alone.[91] The university is working further to make it resistant to mosaic and abacá bract mosaic viruses.[92]

In July 2010, UPLB announced that the Leucinodes orbonalis-resistant Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) eggplant variety that it had been developing with Cornell University and Mahyco was ready for commercialization.[93] On 17 February 2011, Filipino and Indian Greenpeace activists trespassed UPLB's Bay research farm and uprooted two Bt eggplants and more than 100 non-genetically modified eggplants. The National Academy of Science and Technology and ranking UPLB officials condemned the incident, and have taken legal action.[94][95]

Biofuel research[]

Pioneering efforts in biofuel research have been conducted at the university. Studies conducted in the 1930s found that gasoline with 15–20 percent ethanol, dubbed "gasanol", was more efficient than pure gasoline.[86][96] Biofuel research in 2007 under the National Biofuel Program has considered new sources of biofuel, such as coconuts, Moringa oleifera, and sunflower seeds. Efforts have been concentrated on the Jatropha curcas due to its low maintenance and fast yield. Other fuel, such as coconut biofuel, were found to be too costly.[97] Biofuel from Sorghum bicolor, Manihot esculenta crantz and Chlorella vulgaris are also being studied.[98][99][100][101][102]

Student life[]

In 2008, 2,170 students were housed in the eight dormitories managed by UPLB. In the academic year 2011–2012, fees for all UPLB dormitories increased by at least 25 percent from the previous rate of ₱350 (US$8) a month.[16][103] As with the previous dormitory fee increase of 221 percent in 1997,[104] making the dormitories "financially self-supporting" was one of the reasons cited by the University Housing Office for the revision. The move was widely criticized by various groups. The University Housing Office projects ₱13,818,000 (US$322,000)[16] in revenue for 2010 with a deficit of ₱586,465.59 (US$13,600).[16] according to official estimates.[105] UPLB is currently building two new dormitories with 2,000 square metres (22,000 sq ft) of floor area. The new dormitories are expected to accommodate 192 persons annually.[106]

Student Organizations[]

As of May 2020, there are 159 recognized student organizations in UPLB. Of these, 68 are academic, 15 cultural, one international, eight religious, 30 socio-civic, six sports and recreational, 11 varsitarian, 13 fraternities, and 7 sororities.[107] There are also a number of organizations that exist but are not officially recognized by the university.[108] Regional organizations were not recognized by UPLB prior to September 2008, when the University of the Philippines board of regents repealed Chapter 72 Article 444 of the 1984 University of the Philippines Code, which states that "organizations which are provincial, sectional or regional in nature shall not be allowed in the University System." Likewise, Section 3 of the code states that "the University of the Philippines System is a public, secular, non-profit institution of higher learning." Due to this, religious organizations have had some difficulty in getting recognized.[109][110][111] Only recognized organizations are allowed to use UPLB facilities.[112] The system of student organizations in UPLB is different from that of other UP constituents in that freshmen are not allowed to join any organization until they have earned at least 30 units.

Loyalty Day[]

Every 10 October, UPLB celebrates Loyalty Day, which has also become UPLB's alumni homecoming. The celebration commemorates events in 1918 when more than half of students and faculty (193 out of 300 students and 27 out of 32 faculty), including two women, enlisted in the Philippine National Guard for service in France during World War I. The volunteers never saw action as the Allied Forces signed an armistice with Germany during the same year, essentially ending the war.[11][113][114]

Feb Fair[]

The university holds a major campus fair, known as "Feb Fair", during Valentine's week. The fair was initially held to express opposition to martial law under Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, who abolished student organizations and student councils.[115]

Media[]

The militant UPLB Perspective is the official student publication of UPLB. The university administration has been repeatedly criticized for allegedly interfering in the selection process of its editor-in-chief.[116] Other campus publications include UPLB Horizon[117] and UPLB Link.[118] Meanwhile, the College of Development Communication (CDC) publishes the experimental community newspaper Los Baños Times.

CDC runs the radio station DZLB 1116, the oldest educational radio station in the Philippines. Founded in August 1964 with a broadcast power of 250 watts at 1210 kHz, the station serves as a distance education tool and training facility. It currently operates through a five-kilowatt transmitter located near the main gate of the campus. The station was the 1994 recipient of the KBP Golden Dove Award for Best AM Radio Station[119] as well as a Catholic Mass Media Award for Best Educational Radio Program in 2010.[120]

People[]

People associated with the university include alumni, faculty, and honorary degree recipients. They include 16 out of 41 National Scientists of the Philippines: Eduardo A. Quisimbing, 1980 (Plant Taxonomy, Systematics, and Morphology), Francisco M. Fronda, 1983 (Animal Husbandry), Francisco O. Santos, 1983 (Human Nutrition and Agricultural Chemistry), Julian A. Banzon, 1986 (Chemistry), Dioscoro L. Umali, 1986 (Agriculture and Rural Development), Pedro E. Escuro, 1994 (Genetics and Plant Breeding), Dolores A. Ramirez, 1998 (Biochemical Genetics and Cytogenetics), Jose R. Velasco, 1998 (Plant Physiology), Gelia T. Castillo, 1999 (Rural Sociology), Bienvenido O. Juliano, 2000 (Organic Chemistry), Clare R. Baltazar, 2001 (Systematic Entomology), Benito S. Vergara, 2001 (Plant Physiology), Ricardo M. Lantican, 2005 (Plant Breeding), Teodulfo M. Topacio, Jr., 2008 (Veterinary Medicine), Ramon C. Barba, 2014 (Horticulture), and Emil Q. Javier, 2019 (Agriculture).[2] Meanwhile, four UPLB scientists are members of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that won the Nobel Prize in 2007: Rex Victor Cruz, Felino P. Lansigan, Rodel D. Lasco, and Juan M. Pulhin. [7] Scientist Romulo G. Davide was given a Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2012 for “his steadfast passion in placing the power and discipline of science in the hands of Filipino farmers.”[2]

UPLB alumni have served as senior government officials under various administrations. Those currently in office include William Dar (Agriculture secretary),[121] Arsenio Balisacan (head of the Philippine Competition Commission and former Socioeconomic Planning Secretary),[122]and Senator Juan Miguel Zubiri. [123]

Both of its honorary degree recipients held influential roles in their respective countries' politics. They are Salim Ahmed Salim, former Prime Minister of Tanzania,[124] and Sirindhorn, Princess of Thailand.[125]

Former UP presidents Bienvenido Maria Gonzalez (1939-1943; 1945-1951), Emil Q. Javier (1993-1999) and Emerlinda R. Roman (2005-2011) graduated from UPLB.[2] Alumni who held ranking administrative posts at other universities include Weerapon Thongma, President of Maejo University in Thailand and Cristina Padolina, President of Centro Escolar University.[126][127]

San Miguel Corporation Chairman Eduardo Cojuangco Jr. and Bounty Agro Ventures President Ronald Daniel Mascariñas also attended UPLB.[128]

See also[]

- University of the Philippines

- University of the Philippines Baguio

- University of the Philippines Cebu

- University of the Philippines Diliman

- University of the Philippines Manila

- University of the Philippines Mindanao

- University of the Philippines Open University

- University of the Philippines Visayas

References[]

- ^ Solita Collas-Monsod (30 August 2008). "Living up to UP's motto". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "UPLB At A Glance". UPLB. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d "U.P. Statistics 2019" (PDF). University of the Philippines System Budget Office. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Facilities, Equipment and Library Resources". University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Centers of Excellence in Research". UPLB. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "CHED Centers of Excellence and Development". UPLB. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ a b "UP's Climate Change Experts". University of the Philippines System. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "DHUM's Piocos wins in Palanca Awards". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Two DHUM profs big winners at the Palancas". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "UPLB History". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 1–3". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 3–46. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ a b c d "The 1977 Ramon Magsaysay Award for International Understanding". Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "The Los Banos Prison Camp Raid – The Philippines 1945". Osprey Publishing. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Remember Los Baños 1945". Los Baños Liberation Memorial Scholarship Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Sam McGowan (19 August 1999). "World War II: Liberating Los Baños". World War II. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Approximate conversion value as of May 2011

- ^ a b Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 6–8". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 75–122. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ a b Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 9–10". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 123–160. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ a b c d Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Ch. 11–12". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 161–186. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ Ferdinand E. Marcos (20 November 1972). "Presidential Decree No. 58". Arellano Law Foundation. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ a b "La Granja Research and Training Station". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Leandro V. Locsin". Arkitekturang Filipino. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Anjo C. Alimario (29 May 2010). "Mt. Makiling has more tree species than US". Business Mirror. Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Makiling Forest Reserve (MFR)". Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Research and Development. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Citronella Essential Oil Production at the Laguna-Quezon Land Grant". University of the Philippines Los Baños Land Grant Management Office. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "History". University of the Philippines Los Baños Land Grant Management Office. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ "Accomplishments". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Brief History". University of the Philippines Los Baños Land Grant Management Office. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "UP PSAE offers grad programs in entomology, environmental science". University of the Philippines Los Baños. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Damosa Land, UP to establish agri institute in Davao". Manila Times. 20 February 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chapter 17: Milestones in Controversial Times: The David Years (1999–2005)". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 263–278. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chapter 14: UPLB in Clear And Placid Waters: The De Guzman Years (1985–1991)". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 211–226. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ a b Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chapter 15: Pursuing Dreams in a Short Term: The Aspiras Years (1991–1993)". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 227–238. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ Fernando A. Bernardo (6 October 2008). "Chapter 16: UPLB on the Wings: The Villareal Years (1993–1999)". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 239–262. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.[dead link]

- ^ "Alfredo Pascual: "The 20th UP President"". University of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Congress of the Philippines (5 May 2008). An Act to Strengthen the University of the Philippines as the National University (PDF). Manila: Office of the President of the Philippines. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "About UPLB – University Officials". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "University of the Philippines". Association of Pacific Rim Universities. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Basic Student Information". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ University Student Council (12 July 2004). "USC Constitution". Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "History". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "CDC Profile". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "College of Economics and Management". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "CEAT Quick Facts & Timeline". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Engineering and Agro-Industrial Technology. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "About". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "About the Graduate School: History". University of the Philippines Los Baños Graduate School. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "College of Human Ecology". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Human Ecology. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "About". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "About CVM". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ {{cite web|url=https://uplb.edu.ph/academics/ |title=Academics |publisher=University of the Philippines Los Baños |access-date=17 Oct 2021

- ^ "Departments". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "HOW THE EEAS WORKS: A Tale of Two Applicants". 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "UPLB Wait List Criteria 1st SEM AY 2011–2012". 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "UP Waitlist Procedure". 28 February 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ a b "U.P. UPG Cut-Off Scores and Reconsideration". 1 June 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Lex Librero (2008). Development Communication Los Baños Style: A Story Behind the History (PDF). University of the Philippines Open University. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ "What is the UPRHS Entrance Examination?". University of the Philippines Rural High School Office of Admissions and Registration. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "General Information of Validation Examination". University of the Philippines Rural High School. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Graduation with Honors". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Report of the Committee to Review the Socialized Tuition and Financial Assistance Program (STFAP)". University of the Philippines. 7 December 2006. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ a b Aaron Joseph Aspi (27 September 2007). "ToFI Monitor: the real score behind the numbers" (PDF). UPLB Perspective. 34 (1): 1, 4. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Loan Grants". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Veterinary Medicine. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "8 things you need to know about the free tuition law". Rappler.

- ^ "ASEAN University Network-Quality Assurance Certificate". UPLB. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "Search AGRIS from 1975 to date". International Information System for Agricultural Services and Technology. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Brief History, Mission, and Vision". University of the Philippines Los Baños Main Library. 11 March 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "CVM-ADSC Library". University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Veterinary Medicine. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ A.C. Sumalde (December 1999). The Museum of Natural History, University of the Philippines Los Baños, and the Philippine Water Bug Inventory Project (PDF). Vienna: Naturhistorischen Museums Wien. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". ASEAN Center for Biodiversity. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". International Rice Research Institute. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Country offices". World Fish Center. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Site Based Los Banos (Philippines)". World Agroforestry Centre. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "About us". Asia Rice Foundation Philippines. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "APEC ACTETSME". Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "About". DENR ERDB. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "About". DOST FPRDI. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "Contact Us". Philippine Carabao Center. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "Members". DOST PCARRD. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ "Background". Philippine Rice Research Institute. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Michael Whitton (April 2010). "Finding your h-index (Hirsch index) in Google Scholar" (PDF). University of Southampton. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "SJR Journal Search". SCImago. 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Search Results (keyword: Philippines)". Web of Science Group. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Caroline Ann S. Diezmo; Sophia Anne R. (15 February 2010). "UPLB opens its doors to biotech companies". University of the Philippines Los Baños Horizon. University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 4–5". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association. pp. 47–74. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ Jaymee T. Gamil (29 July 2007). Philippine Daily Inquirer https://web.archive.org/web/20120311075414/http://services.inquirer.net/print/print.php?article_id=20070729-79283. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Marvyn N. Benaning (8 September 2010). "Makapuno RP's First Biotech Crop". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Joel C. Paredes (11 January 2011). "UPLB scientists developing delayed-ripening papaya". Business Mirror. University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Paul Icamina (27 November 2011). "Tripling yields, placing mangoes on world market year-round". Malaya. University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Danny O. Calleja (5 June 2009). "Abaca researchers turn to biotechnology in efforts to save Manila hemp exports". Business Mirror. Manila: University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Jo Florendo B. Lontoc (31 May 2007). "UP scientists trying to help abaca industry". Business World. Department of Agriculture Biotechnology Program. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Rudy A. Fernandez (25 June 2010). "RP's 1st GM eggplant soon ready for commercialization". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Office of Public Relations (22 February 2011). "UPLB, NAST issue statement against Greenpeace violators". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Rudy A. Fernandez (21 February 2011). "UPLB to charge activists for ruining GM eggplants". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 8 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Rudy A. Fernandez (29 May 2007). "Saga of the Biofuel: The Philippine Experience". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ KIM Quilinguing (May 2009). "UPLB continues search for the most viable biofuel". UP Newsletter. Quezon City: University of the Philippines. 30 (5). Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ Bernice P. Varona (1 April 2011). "Power plants: University spearheads biofuel R&D". UP Newsletter. Quezon City: University of the Philippines. 32 (4). Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ Florante Cruz (7 June 2009). "Philippines' quest for diesel from microalgae starts at UPLB". Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ Mervin John C. De Roma (11 September 2010). "UPLB gears up for third generation biodiesel". University of the Philippines Los Baños Horizon. University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ Jay Francis M. Bilowan (20 September 2010). "Microalgae: The ultimate source of biodiesel in the future — UPLB". ZamboTimes. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ "Researchers to produce bioethanol from grass, wood and by-products in 5 years". Balita. Philippine News Agency. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ Margaret M. Calderon (28 March 2011). New dorm fees (PDF). University of the Philippines Los Baños Housing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Caroline Ann Diezmo (27 September 2007). "DFI: Tuloy ang laban ng iskolar ng bayan" (PDF). UPLB Perspective (in Tagalog). p. 7. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Estel Lenmu Estropia (21 February 2011). "UHO reviews dorm policies". UPLB Perspective. 37 (1): 3. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ JAA Oruga (9 June 2009). "UPLB to build two new dorms". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "List of Recognized Organizations - Second Semester, AY 2019-2020". Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "SOAD-OSA: List of Organizations". Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Yves Christian Suiza (17 December 2008). "Recognition ng religious orgs, nakabinbin pa rin" (PDF). UPLB Perspective (in Tagalog). 35 (5): 3. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Katrina Elauria (4 September 2008). "OSA holds recognition of religious, varsitarian orgs". UPLB Perspective. 35 (2): 2, 9. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Faith Allyson Buenacosa; et al. (29 January 2009). "OSA withholds recognition of orgs". UPLB Perspective. 35 (7): 7. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Maricar Cino (16 December 2010). "UP budget slash marks APO run in Los Baños campus". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ MM Catibog. "89th UPLB Loyalty Day and Alumni Homecoming". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "UP ROTC Los Baños Unit". Armed Forces of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Nikko Caringal (13 March 2009). "Students assess centennial feb fair". UPLB Perspective. 35 (9): 3–4. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Ronalyn V. Olea (10 July 2004). "UPLB Chancellor Meddles in School Paper Exam Anew". Bulatlat. Manila. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "UPLB Horizon". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "UPLB Link". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ UPLB. UPLB Link. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Open University. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ "The Envelope: CMMA 2010 Winners". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ "William Dolente Dar". DOST. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ UPSE. "Arsenio M. Balisacan". UPSE. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Biography". Official Website of Sen. Juan Miguel F. Zubiri. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Salim Ahmed Salim (PDF). Dar-es-Salam. January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "UP confers honorary doctor of laws on Thai Princess Tuesday". Manila Bulletin. 16 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Madel R. Sabater (9 June 2006). "New frameworks for Math and Science to focus on critical thinking and scientific literacy". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "The University Presidents". Centro Escolar University. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Mascariñas, Bounty's top man to speak before UPLB Class of 2021". UPLB. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of the Philippines Los Baños. |

- University of the Philippines Los Baños

- Universities and colleges in Laguna (province)

- Research universities in the Philippines

- Educational institutions established in 1909

- 1909 establishments in the Philippines

- Education in Los Baños, Laguna

- Forestry education

- History of forestry education