Ontario Provincial Police

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Ontario Provincial Police Police provinciale de l'Ontario | |

|---|---|

Heraldic badge of the OPP | |

Shoulder flash of the OPP | |

OPP flag | |

| Abbreviation | OPP |

| Motto | Safe Communities, A Secure Ontario |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 13 October 1909[1] |

| Employees | 5,500 uniformed officers 700 auxiliary officers 2,500 civilian employees[2] |

| Annual budget | $1,162,690,448 (CAD), 2019–2020 operating expenses |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Ontario, Canada |

| Governing body | Ministry of the Solicitor General |

| Constituting instrument | |

| General nature |

|

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | 777 Memorial Avenue Orillia, Ontario, Canada |

| minister responsible | |

| Agency executive |

|

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 170[4] |

| Website | |

| www.opp.ca | |

The Ontario Provincial Police (OPP; French: Police provinciale de l'Ontario) is the provincial police service of Ontario. Under its provincial mandate, the OPP patrols provincial highways and waterways, protects provincial government buildings and officials, patrols unincorporated areas, and provides support to other agencies. The OPP also has a number of local mandates through contracts with municipal governments, where it acts as the local police force and provides front-line services.

With an annual budget of nearly $1.2 billion dollars,[5] the OPP employed 5,500 uniformed officers, 700 auxiliary officers, and 2,500 civilian employees in 2020,[2] making it the largest police service in Ontario and the second-largest in Canada (after the Royal Canadian Mounted Police). The OPP's operations are directed by its commissioner (Thomas Carrique since 2019) and it is a part of the Ministry of the Solicitor General.[6]

History[]

At the First Parliament of Upper Canada in Niagara-on-the-Lake on 17 September 1792, a provision was made for the formation of a "police system". Initially, policing jurisdictions were limited to districts, townships, and parishes. In 1845, a mounted police service was created to keep the peace in areas surrounding the construction of public works.[7] It became the Ontario Mounted Police Force after Canadian Confederation.

In 1877, the Constables Act extended jurisdiction and gave designated police members authorization to act throughout the province.[8] The first salaried provincial constable appointed to act as detective for the government of Ontario was John Wilson Murray, hired on a temporary appointment in 1875 and made permanent upon passage of the 1877 act. Murray was joined by two additional detectives in 1897, marking the beginnings of the Criminal Investigation Branch. However, for the most part, policing outside of Ontario's cities was non-existent.

With the discovery of silver in Cobalt and gold in Timmins, lawlessness was increasingly becoming a problem in northern Ontario. Police constables were gradually introduced in various areas,[9] until an Order in Council decreed the establishment of a permanent organization of salaried constables designated as the Ontario Provincial Police Force on 13 October 1909.[10] It consisted of 45 men under the direction of Superintendent Joseph E. Rogers. The starting salary for constables was $400 per annum, increased to $900 in 1912. There were many detachments simultaneously founded including Bala, Muskoka, and Niagara Falls.[11]

In the 1920s, restructuring was undertaken with the passing of the Provincial Police Force Act, 1921.[12] The title of the commanding officer was changed to "commissioner" and given responsibility for enforcing the provisions of the Ontario Temperance Act[13] and other liquor regulations. Major-General Harry Macintyre Cawthra-Elliot was appointed as the first commissioner.

The OPP's first death in the line of duty occurred in 1923, when escaped convict Leo Rogers shot and killed Sergeant John Urquhart near North Bay. Rogers, who was later killed in a shootout with OPP officers, had already mortally wounded North Bay City constable, Fred Lefebvre.

The first OPP motorcycle patrol was introduced in 1928, phased out in 1942, and then reintroduced in 1949. The first marked OPP patrol car was introduced in 1941.

During World War II, the Veterans Guard was formed. This was a body of volunteers (primarily World War I veterans) whose duty was to protect vulnerable hydroelectric plants and the Welland Ship Canal under the supervision of regular police members.

In the late 1940s, policing functions were reorganized in Ontario, with the OPP given responsibility for all law enforcement in the province outside areas covered by municipal police forces, together with overall authority for law enforcement on the King's Highways, enforcement of the provincial liquor laws, aiding the local police, and maintaining a criminal investigation branch.[14] In March 1969, a meeting took place at the Ontario Securities Commission to incorporate a separate but included group of the Ontario Provincial Police Association.[15] Women joined the uniformed ranks in 1974.

In 1994, as part of a tripartite agreement between the government of Canada, the Province of Ontario, and the Nishnawbe Aski Nation, the OPP began the process of relinquishing a majority of northern policing duties to the newly created Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service (NAPS). The transition was complete on 1 April 1999, when the OPP's Northwest Patrol was transferred to NAPS. The OPP still administers First Nations policing for Big Trout Lake, Weagamow, Muskrat Dam, and Pikangikum.[16]

Organization and operations[]

The Ontario Provincial Police provide policing services to areas of Ontario not policed by a regional or municipal police service. Municipalities can also be policed by the OPP under contract, with 323 as of 2019.[17] Some detachments also host satellite detachments that provide policing to a local area, covering more than one million square kilometers, approximately 128,000 kilometers of provincial highway, and a population of over 13 million people.[18] The OPP General Headquarters is currently located at 777 Memorial Avenue in Orillia at the Lincoln M. Alexander Building. The relocation of general headquarters to Orillia was part of a government move to decentralize ministries and operations to other parts of Ontario. Previously, from 1973 to 1995, the headquarters were located in Toronto at 90 Harbour Street, the site of the former Workmen's Compensation Board building.

The OPP also works with other provincial agencies, including the Ministry of Transportation and Ministry of Natural Resources, to enforce highway safety and conservation regulations, respectively. Finally, OPP officers provide security at the Legislative Assembly of Ontario in Toronto.

Detachments[]

Previously, the OPP was divided into seventeen different regions. In 1995, OPP operations were amalgamated into six regions, with five providing general policing services, and one providing traffic policing services in the Greater Toronto Area following recommendations by the Ipperwash Inquiry.[19] OPP police stations are known as "detachments".

| No. | Region | Headquarters | Duties | Detachments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Central | Orillia | General policing | Bracebridge, Caledon, City of Kawartha Lakes, Collingwood, Dufferin County, Haliburton Highlands, Huntsville, Huronia West, Northumberland County, Northumberland County (Campbellford), Northumberland County (Brighton), Nottawasaga, Orillia, Orillia (Barrie), Peterborough County, Southern Georgian Bay, Southern Georgian Bay (Midland) | |

| 2 | Northwest | Thunder Bay | General policing | Dryden, Dryden (Ignace), Greenstone, Kenora, Kenora (Sioux Narrows), Marathon, Marathon (Manitouwadge), Nipigon, Nipigon (Schreiber), Rainy River District, Rainy River District (Atikokan), Rainy River District (Emo), Rainy River District (Rainy River), Red Lake, Red Lake (Ear Falls), Sioux Lookout, Sioux Lookout (Pickle Lake), Thunder Bay, Thunder Bay (Shabaqua), Thunder Bay (Armstrong) | |

| 3 | East | Smith Falls | General policing | Bancroft, Central Hastings, Frontenac, Frontenac (Sharbot Lake), Grenville, Hawkesbury, Killaloe, Killaloe (Whitney), Lanark County, Lanark County (Carleton Place), Leeds County, Leeds County (Thousand Islands), Leeds County (Rideau Lake), Lennox and Addington County, Lennox and Addington County (East), Lennox and Addington County (North), Prince Edward County, Quinte West, Renfrew, Renfrew (Arnprior), Russell County, Russell County (Rockland), Stormont Dundas and Glengarry, Stormont Dundas and Glengarry (Alexandria), Stormont Dundas and Glengarry (Lancaster), Stormont Dundas and Glengarry (Morrisburg), Stormont Dundas and Glengarry (Winchester), Upper Ottawa Valley, Upper Ottawa Valley (Pembroke) | |

| 4 | Northeast | North Bay | General policing | Almaguin Highlands, East Algoma, East Algoma (Elliot Lake), East Algoma (Thessalon), James Bay, James Bay (Hearst), James Bay (Cochrane), James Bay (Moosonee) Kirkland Lake, Manitoulin, Manitoulin (Gore Bay), Manitoulin (Little Current), Manitoulin (Mindemoya), Manitoulin (Espanola), North Bay, North Bay (Mattawa), North Bay (Powassan), Sault Ste. Marie, South Porcupine, South Porcupine (Iroquois Falls), South Porcupine (Gogama), South Porcupine (Matheson), South Porcupine (Foleyet), Sudbury, Sudbury (Noelville), Sudbury (Warren), Sudbury (Nipissing West), Superior East, Superior East (Chapleau), Superior East (Hornepayne), Superior East (White River), Temiskaming, Temiskaming (Englehart), Temiskaming (Temagami), West Parry Sound, West Parry Sound (Still River) | |

| 5 | Highway Safety Division | Aurora | Traffic policing | Aurora, Aurora (Barrie), Burlington, Burlington (Niagara), Cambridge, Highway 407, Highway 407 (Burlington), Port Credit, Toronto, Toronto (Whitby) | |

| 6 | West | London | General policing | Brant County, Chatham-Kent, Elgin County, Essex County, Essex County (Harrow), Essex County (Kingsville), Essex County (Lakeshore), Essex County (Leamington), Essex County (Tecumseh), Grey County, Grey County (Markdale), Grey County (Meaford), Grey County (Wiarton), Haldimand County, Huron County, Huron County (Exeter), Huron County (Wingham), Huron County (Goderich), Lambton County, Lambton County (Corunna), Lambton County (Grand Bend), Lambton County (Point Edward), Middlesex County, Middlesex County (Strathroy), Middlesex County (Glencoe), Middlesex County (London), Middlesex County (Lucan) Norfolk County, Oxford County, Oxford County (Ingersol) Perth County, Perth County (Listowel), Perth County (Mitchell), South Bruce, South Bruce (Walkerton), Wellington County, Wellington County (Rockwood), Wellington County (Teviotdale) |

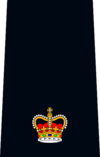

Rank structure[]

The rank structure within the OPP is paramilitary or quasi-military in nature, like most North American law enforcement services, with several "non-commissioned" ranks leading to the "officer" ranks. Detective ranks fall laterally with the uniform ranks and is not a promotion above. Police constables in the OPP are uniquely known as "provincial constables".

Sworn rank insignia[]

| Rank | Commissioner | Deputy commissioner | Chief superintendent | Superintendent | Inspector | Sergeant major | Staff sergeant / Detective staff sergeant | Sergeant / Detective sergeant | Provincial constable / Detective constable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insignia |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Civilian rank insignia[]

| Title | Special constable | Special constable | Auxiliary constable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insignia |  |

|

|

| Notes | Queens Park, GHQ security | Digital forensics, forensic investigators, court security, offender transport | Auxiliary policing program |

Commissioner's Own Pipes and Drums[]

The Commissioner's Own Pipes and Drums serves as the OPP's officially recognised pipe band. Formed as the Ontario Provincial Pipes and Drums in 1968 by two constables, the band saw active service to wide acclaim in the 1970s and 80s before being disbanded in 1991 due to department financial constraints. The band was shortly re-formed three years after, and is now composed of volunteer officers, auxiliary officers, and civilian volunteers.[20]

Legislative Security Service[]

The Legislative Security Service is a division of the OPP consisting of sworn officers who provide security services to Ontario’s Legislative Precinct (Legislature Building at Queen's Park and the adjacent Whitney Block) in Toronto. While administratively part of the OPP, they report to the sergeant-at-arms, an officer appointed by the legislature (and not the government of Ontario), who commands the service.[21] Within the service, there are two classes of legislative protection personnel: unarmed special constables (who patrol the precinct when not in session) and armed peace officers (on duty when the legislature is in session, and during special occasions such as public demonstrations).

Special constable uniforms consist of a white shirt, black tactical vest, radio, black pants with yellow stripe and peaked cap.[citation needed] Peace officers wear similar uniforms, but with black shirts and black pants with single red stripes. They also carry the OPP's standard issue sidearm – a Glock 17M pistol in 9x19mm – for protection. In the event of a dangerous incident, tactical assistance is provided by the Emergency Service Unit of the Toronto Police Service, whose headquarters is proximate to the precinct on College Street. For an immediate response, officers may also access tactical weaponry from the Queen's Park armoury located within the legislature building.

Uniformed officers[]

The majority of policing services are provided by uniformed front-line police constables, who attend the Ontario Police College in Aylmer, Ontario, for thirteen weeks to obtain their Basic Constable Training Diploma. The OPP also mandates additional training before and after attendance at the Ontario Police College, resulting in the longest training period among Ontario police services. After this, probationary police constables are assigned to a detachment within the OPP's six regions with a coach officer for a year of field training. At the end of probation, a decision is made regarding retention.[citation needed]

The OPP conducts training at the Provincial Police Academy in Orillia, Ontario. The current academy was opened in 1998 on the site of the former Huronia Regional Centre. Previously, training was conducted at the OPP Training and Development Centre in Brampton, Ontario, from 1981 to 1998. Uniquely, the OPP also has the mandate to train First Nations constables from the OPP administered First Nations police services. Members of these services undergo the same training as OPP constables, save a different uniform. Academy attendance is not open to the general public.[citation needed]

Uniformed non-commissioned OPP officers wear dark blue uniforms with gold lettering and shoulder flashes. Commissioned officers wear different shoulder flashes, and white shirts. Since 1985, wide, light blue stripes down the side of issued trousers have been standard, and forage caps are banded with hat bands of the same colour. Officers wear duty belts with issued equipment, and have the option of wearing either an internal ballistic vest, or an external tactical vest with MOLLE webbing and large placards indicating "police" on their chest and back. The OPP was the first major police service in Canada to issue tourniquets and trauma equipment to each officer. Previously, officer were issued light blue shirts instead of their current navy blue shirts. These shirts are now reserved for use by special constables, security officers, and auxiliary police constables. From 1997 to 2008, the official headdress of the OPP was the stetson, though commissioned ranks were still issued the forage cap. Starting in 2008, the OPP returned to the peaked cap for all officers. Officers in a specialized role are issued different equipment, such as baseball caps. Officers serving with specialty tactical units may also be issued cargo pants without the distinctive stripe, utility tops, and subdued placards for their external tactical vests. Officers serving with the Tactics and Rescue Unit are issued olive green uniforms.[citation needed]

Auxiliary program[]

Auxiliary members have no police authority. They must rely on the same arrest provisions as regular citizens. There are some instances when an auxiliary member may have the authority of a police officer. This can occur in an emergency situation, or where the OPP requires additional strength to assist with a special event. Auxiliary officers are unpaid, however are compensated for travel and meals. They are required to attend routine training administered by the OPP, and must contribute a certain number of hours monthly. The auxiliary is made up of people from diverse backgrounds.[citation needed]

Auxiliary members are trained at the Provincial Police Academy and qualified with all use of force options.[citation needed]

The auxiliary uniform is distinct from the uniform of a regular OPP officer. Auxiliary officers wear light blue shirts, checkered hat bands, and have their own cap badges. They wear slip-ons with the word "auxiliary" embroidered on them, and their jackets and dress uniforms have tabs sewn on that indicates that they are auxiliary officers.[citation needed]

History[]

Following the disbanding of World War II auxiliary forces, growing Cold War tension and fear of a nuclear attack led to the belief that police services should "recruit and train volunteers to augment their strength in times of emergency". As a result, in 1954, the Provincial Civil Defence Auxiliary was created, but the need to more closely associate the auxiliary with the OPP soon became apparent.[citation needed]

On 14 January 1960, the Provincial Civil Defence Organization was dissolved. A new oversight body known as the Emergency Measures Organization—Ontario (EMO) came into being. Each department of the government became responsible for its own operational planning. The organization of auxiliary police forces became the responsibility of all interested municipal police forces, as well as the OPP.[citation needed]

In April 1960, a new organization more closely affiliated with the OPP came into being. The Ontario Auxiliary Police were organized in 12 of the 17 OPP districts and by the end of the year, 376 volunteers had signed up to be equipped and trained by experienced OPP personnel. Two OPP inspectors were assigned to work with Emergency Measures Ontario as liaison officers for the volunteers. This close connection continues today with the OPP auxiliary playing a critical role in emergency and disaster planning and occurrences. By 1961 there were 466 auxiliary volunteers who accompanied regular provincials on traffic and law enforcement patrols and during the year logged more than twenty-six thousand hours of volunteer duty.[22]

Fleet[]

The vehicle fleet consists of 2,290 vehicles, 114 marine vessels, 286 snow and all-terrain vehicles, two helicopters, and two fixed-wing aircraft.

Ground[]

The OPP has approximately 1,200 cruisers in service across the province. Officers use all-wheel drive versions of the Ford Taurus, Ford Explorer, Dodge Charger and Chevrolet Tahoe for front line patrol. For specialized roles, a variety of vehicles are used, such as the Chevrolet Suburban, Ford F250 Super Duty, and the Cambli International Thunder 1 armoured rescue vehicles used by the Tactics and Rescue Unit, as well as an International-based truck used by the Highway Safety Division and Mobile Support Units. Previously, models of the Ford Crown Victoria and Chevrolet Impala were used.[citation needed]

Historically, from 1941 to 1989, the OPP livery was black and white. In 1989, in response to manufacturers no longer offering dual tone vehicles, the OPP switched to an all-white livery with blue and gold striping.[23] Vehicles of this era were equipped with Federal Signal's Vector light bars with integrated traffic advisers. In 2007, the OPP announced that it would return to a black and white colour scheme. The colour scheme is accomplished with the use of vinyl wraps during in-house vehicle outfitting. The change was implemented starting in March 2007 and was completed in 2009.[citation needed] Vehicles of this era had detachment markings on the rear quarter panel and used Federal Signal Arjent S2 light bars. Current vehicles have eschewed the detachment markings and are equipped with Whelen Legacy light bars. Unmarked vehicles are generally white, black, grey or dark blue. All marked cruisers are equipped with pushbars, also generally have black steel rims, and spotlights mounted on the driver side. Licence plates on the cruisers are generally the standard Ontario licence plates with a special validation sticker denoting permanent registration.[24]

Aviation[]

- Eurocopter EC135

- Pilatus PC12NG

- Cessna 206 Turbo

Marine[]

- Kanter Marine "Chris D. Lewis" 38-foot police boat

UAV[]

- Draganflyer X6 UAV[25]

- FIU-301 UAS

Weapons[]

Ontario Provincial Police officers carry a variety of use of force equipment in the performance of their duties. The current sidearm of the OPP is the Glock 17M pistol in 9x19mm. Previously, officers were issued either the Sig Sauer P229 DAO, or the P229R DAK in .40S&W. Patrol vehicles are also equipped with the Colt Canada C8 patrol rifle in 5.56x45mm NATO, with the option of the Remington 870 in 12 gauge. All uniformed officers carry TASER X2 conducted energy weapons.[citation needed]

The Tactics and Rescue Unit have more specialized weapons at their disposal including:

- Accuracy International AW

- Armalite AR10

- Colt Canada C8 patrol CQB carbine

- Knights Armament SR25

- Heckler & Koch MP5

Controversies[]

Caledonia land dispute[]

The Caledonia land dispute began in 2006 when members of the Six Nations of the Grand River began an occupation of land that they believed belonged to them, to bring light to their land claims, and to the plight of aboriginal land claims across Canada.[citation needed] The land at the centre of the dispute was owned by a corporation planning to build a subdivision known as the Douglas Creek Estates. The Ontario Provincial Police were called in to keep the peace. Tensions led to violence and over the span of several years, the Ontario Provincial Police were criticized for perceived inaction against the native protesters by local residents. In 2011, a class-action lawsuit against the government of Ontario was settled.[citation needed]

Ipperwash Crisis[]

The Ipperwash Provincial Park is a former provincial park in Lambton County, Ontario. On 4 September 1995, first nations people occupied the park to bring attention to decades-old land claims that had not been recognized, resulting in the Ipperwash Crisis. The park had been expropriated from the Stoney Point Ojibway during World War II. The protest increased in tensions, resulting in the shooting and subsequent death of a protestor, Anthony O'Brien "Dudley" George, by Acting Sergeant Ken Deane of the Tactics and Rescue Unit. Deane was subsequently convicted of criminal negligence causing death. In 2003, an inquiry called the Ipperwash Inquiry, into the events at Ipperwash was convened, and concluded in 2007. The OPP now uses a variety of different methods in resolving conflicts at major events, most notably by the use of the Provincial Liaison Teams (PLT), formerly known as the Major Event Liaison Team (MELT)[26]

John Doe v. Ontario (Information and Privacy Commissioner)[]

In 1993 an Ontario Divisional Court case, John Doe v. Ontario (Information and Privacy Commissioner), Judge Matlow of the Ontario Divisional Court, suspected that four officers of the Toronto Police Service engaged in a fabrication of evidence and harassment of an accused party. Judge Matlow under the Ontario Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA), sought access to the report of the Ontario Provincial Police exonerating the officers, but was denied access to it by the OPP. Access was later granted by the FIPPA commissioner, but a judicial review of the FIPPA commissioner's order to release the report resulted in publication of the OPP report being banned.[27]

Ontario Provincial Police Association[]

The OPPA was established in 1954 to represent sworn and civilian members of the OPP, as well as OPP retirees.[28] In March 2015, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police announced they were investigating fraud allegations against three top executives of the OPPA.[29]

Appointment of Ron Taverner[]

In 2018, Toronto Police Superintendent Ron Taverner, was nominated to replace outgoing Commissioner Vince Hawkes.[30] The appointment of Taverner brought about controversy given the personal relationship between him and Premier Doug Ford, potential nepotism, and the OPP's role in investigating political corruption.[31] It was also discovered that the requirements of the position were changed to allow someone in rank equivalent to Taverner to apply. Ultimately, Taverner rescinded his interest in the position, resulting in the appointment York Regional Police Deputy Chief Thomas Carrique as the OPP's new commissioner.[32]

In culture[]

The Beatles's 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band contains cover art with Paul McCartney wearing an OPP patch on his fictional uniform (more easily seen in the gatefold picture). In January 2016 the origins of the patch was confirmed as a gift from an OPP corporal on 28 September 1964, at Malton Airport as the Beatles were on their way to Montreal.[33]

On the online social networking website Habbo Hotel Canada, OPP officers and spokespersons visit the online application to talk to teens on board the web site's "Infobus". During the weekly sessions, users of the Habbo service are able to ask the officers and spokespersons questions, primarily regarding online safety.

Film and television[]

In the television series Cardinal, the OPP is fictionalized as the Ontario Police Department (OPD), with a shoulder patch similar to that of the actual OPP except that the top element is replaced by three stylized maple leaves on a branch. OPP cruisers in the series are marked similar to actual cruisers, however the Queen's crown is replaced with a stylized beaver, and the vehicles are marked "O.P.D." instead of "O.P.P." In 2016, the Discovery Channel aired the reality TV series Heavy Rescue: 401, following members of the OPP and local heavy tow operators, profiling their efforts during events and routine operations on Highway 401, a highway that crosses southern Ontario.

In the Canadian horror film Pontypool, the OPP is called into the eponymous town to control a zombie outbreak, ultimately resulting in a massacre. The response of the government to this outbreak draws many parallels to Canadian separatist movements. The film's lead character, Grant Mazzy, vocally denounces the OPP's actions on the radio.

References[]

- ^ "The OPP Museum – Historical Highlights of the Ontario Provincial Police". Ontario Provincial Police. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Who We Are". Ontario Provincial Police. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "Office of the Commissioner". Ontario Provincial Police. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "Ontario Provincial Police Detachment List". Ontario Provincial Police. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "Expenditure Estimates for the Ministry of the Solicitor General (2021-22)". www.ontario.ca. Treasury Board Secretariat. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "INFO-GO | Government of Ontario Employee and Organization Directory". www.infogo.gov.on.ca. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ An Act for the better preservation of the Peace, and the prevention of Riots and violent Outrages at and near Public Works while in progress of Construction, S.C. 1845, c. 6, s. 14 , later replaced by The Public Works Peace Preservation Act, S.O. 1910, c. 12, s. 13

- ^ An Act respecting Constables, S.O. 1877, c. 20

- ^ under The Mines Act, 1906, S.O. 1906, c. 24, s. 190

- ^ confirmed by The Constables Act, S.O. 1910, c. 39, s. 17

- ^ https://www.opp.ca/museum/historicalhighlights.php

- ^ The Provincial Police Force Act, 1921, S.O. 1921, c. 45

- ^ The Ontario Temperance Act, S.O. 1916, c. 50

- ^ The Police Act, 1946, S.O. 1946, c. 72, s. 3 , later replaced by The Police Act, 1949, S.O. 1949, c. 72

- ^ https://oppva.ca/

- ^ http://www.naps.ca/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50&Itemid=55

- ^ http://opp.ca/index.php?id=121

- ^ https://www.opp.ca/index.php?id=121

- ^ https://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/ipperwash/policy_part/projects/pdf/Tab4_OPPEmergencyResponseServicesAComparisonof1995to2006.pdf Ipperwash Inquiry

- ^ Police, Ontario Provincial. "OPP Commissioner's Own Pipes and Drums Celebrate their beginnings at Nipigon Concert". wawa-news.com. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Ontario Provincial Police". www.opp.ca. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ https://www.flickr.com/photos/ontarioprovincialpolice/16928270581

- ^ https://europlate.org/Ontario

- ^ "Draganfly Innovations Inc". www.draganfly.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ^ https://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/ipperwash/policy_part/projects/pdf/Tab4_OPPEmergencyResponseServicesAComparisonof1995to2006.pdf

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "OPPA – OPP Association History". www.oppa.ca. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ "'Unusual transactions' in OPP union funds among allegations against top execs". 13 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015.

- ^ https://toronto.citynews.ca/2018/11/29/tps-supt-ronald-taverner-named-opp-commissioner/

- ^ https://globalnews.ca/news/4754529/doug-ford-opp-ron-taverner-ombudsman-review/

- ^ https://www.tvo.org/article/the-ron-taverner-controversy-shows-that-sometimes-the-system-works

- ^ "Sgt. Pepper's iconic photos reveal OPP badge on Paul McCartney's uniform – Toronto Star". Archived from the original on 29 June 2017.

Further reading[]

- Higley, Dahn (1984). O.P.P.: The history of the Ontario Provincial Police Force. Toronto: Queen's Printer. ISBN 0-7743-8964-8.

- Barnes, Michael (1991). Policing Ontario: The OPP Today. Erin: Boston Mills Press. ISBN 1-55046-015-3.

- Maksymchuk, Andrew F. (2008). From MUSKEG to MURDER: Memories of Policing Ontario's Northwest. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-7089-9.

- Maksymchuk, Andrew F. (2014). "Champions of the Dead": OPP Crime-fighters Seeking Proof of the Truth. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-4602-4828-7.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ontario Provincial Police. |

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Ontario Provincial Police Website

- Road Watch, was started by the Caledon, Ontario Provincial Police detachment.

Coordinates: 44°34′59″N 79°25′48″W / 44.583°N 79.430°W

- Ontario Provincial Police

- Government agencies established in 1909

- Law enforcement agencies of Ontario

- 1909 establishments in Ontario

- Orillia

- Protective security units