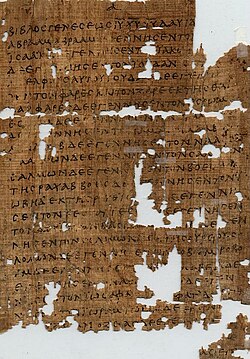

Oxyrhynchus Papyri

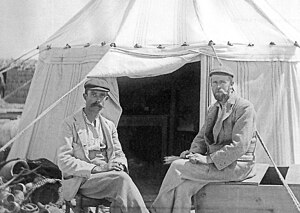

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri are a group of manuscripts discovered during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by papyrologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt at an ancient rubbish dump near Oxyrhynchus in Egypt (28°32′N 30°40′E / 28.533°N 30.667°E, modern el-Bahnasa).

The manuscripts date from the time of the Ptolemaic (3rd century BC) and Roman periods of Egyptian history (from 32 BC to the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 640 AD).

Only an estimated 10% are literary in nature. Most of the papyri found seem to consist mainly of public and private documents: codes, edicts, registers, official correspondence, census-returns, tax-assessments, petitions, court-records, sales, leases, wills, bills, accounts, inventories, horoscopes, and private letters.[1]

Although most of the papyri were written in Greek, some texts written in Egyptian (Egyptian hieroglyphics, Hieratic, Demotic, mostly Coptic), Latin and Arabic were also found. Texts in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac and Pahlavi have so far represented only a small percentage of the total.[2]

Since 1898, academics have collated and transcribed over 5,000 documents from what were originally hundreds of boxes of papyrus fragments the size of large cornflakes. This is thought to represent only 1 to 2% of what is estimated to be at least half a million papyri still remaining to be conserved, transcribed, deciphered and catalogued. At the time of writing, the last published volume was Vol. LXXXVI, released on 30 November 2021.

Oxyrhynchus Papyri are currently housed in institutions all over the world. A substantial number are housed in the Sackler Library at Oxford University. There is an online table of contents briefly listing the type of contents of each papyrus or fragment.[3]

Administrative texts[]

Administrative documents assembled and transcribed from the Oxyrhynchus excavation so far include:

- The contract of a wrestler agreeing to throw his next match for a fee.[4]

- Various and sundry ancient recipes for treating haemorrhoids, hangovers and cataracts.[5]

- Details of a grain dole mirroring a similar program in the Roman capital.[6]

Secular texts[]

Although most of the texts uncovered at Oxyrhynchus were non-literary in nature, the archaeologists succeeded in recovering a large corpus of literary works that had previously been thought to have been lost. Many of these texts had previously been unknown to modern scholars.

Greek[]

Several fragments can be traced to the work of Plato, for instance the Republic, Phaedo, or the dialogue Gorgias, dated around 200-300 CE.[7]

Historiography[]

Another important discovery was a papyrus codex containing a significant portion of the treatise The Constitution of the Athenians, which was attributed to Aristotle and had previously been thought to have been lost forever.[8] A second, more extensive papyrus text was purchased in Egypt by an American missionary in 1890. E. A. Wallis Budge of the British Museum acquired it later that year, and the first edition of it by British paleographer Frederic G. Kenyon was published in January, 1891.[9] The treatise revealed a massive quantity of reliable information about historical periods that classicists previously had very little knowledge of. Two modern historians even went so far as to state that "the discovery of this treatise constitutes almost a new epoch in Greek historical study."[10] In particular, 21–22, 26.2–4, and 39–40 of the work contain factual information not found in any other extant ancient text.[11]

The discovery of a historical work known as the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia also revealed new information about classical antiquity. The identity of the author of the work is unknown; many early scholars proposed that it may have been written by Ephorus or Theopompus,[12] but many modern scholars are now convinced that it was written by Cratippus.[13] The work has won praise for its style and accuracy[14] and has even been compared favorably with the works of Thucydides.[15]

Mathematics[]

The findings at Oxyrhynchus also turned up the oldest and most complete diagrams from Euclid's Elements.[16] Fragments of Euclid discovered led to a re-evaluation of the accuracy of ancient sources for The Elements, revealing that the version of Theon of Alexandria has more authority than previously believed, according to Thomas Little Heath.[17]

Drama[]

The classical author who has most benefited from the finds at Oxyrhynchus is the Athenian playwright Menander (342–291 BC), whose comedies were very popular in Hellenistic times and whose works are frequently found in papyrus fragments. Menander's plays found in fragments at Oxyrhynchus include Misoumenos, Dis Exapaton, Epitrepontes, Karchedonios, Dyskolos and Kolax. The works found at Oxyrhynchus have greatly raised Menander's status among classicists and scholars of Greek theatre.

Another notable text uncovered at Oxyrhynchus was Ichneutae, a previously unknown play written by Sophocles. The discovery of Ichneutae was especially significant since Ichneutae is a satyr play, making it only one of two extant satyr plays, with the other one being Euripides's Cyclops.[18][19]

Extensive remains of the Hypsipyle of Euripides and a life of Euripides by Satyrus the Peripatetic were also found at Oxyrhynchus.

Poetry[]

- Poems of Pindar. Pindar was the first known Greek poet to reflect on the nature of poetry and on the poet's role.

- Fragments of Sappho, Greek poet from the island of Lesbos famous for her poems about love.

- Fragments of Alcaeus, an older contemporary and an alleged lover of Sappho, with whom he may have exchanged poems.

- Larger pieces of Alcman, Ibycus, and Corinna.

- Passages from Homer's Iliad. See Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 20 – Iliad II.730-828 and Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 21 – Iliad II.745-764

Latin[]

An epitome of seven of the 107 lost books of Livy was the most important literary find in Latin.

Christian texts[]

Among the Christian texts found at Oxyrhynchus, were fragments of early non-canonical Gospels, Oxyrhynchus 840 (3rd century AD) and Oxyrhynchus 1224 (4th century AD). Other Oxyrhynchus texts preserve parts of Matthew 1 (3rd century: P2 and P401), 11–12 and 19 (3rd to 4th century: P2384, 2385); Mark 10–11 (5th to 6th century: P3); John 1 and 20 (3rd century: P208); Romans 1 (4th century: P209); the First Epistle of John (4th-5th century: P402); the Apocalypse of Baruch (chapters 12–14; 4th or 5th century: P403); the Gospel according to the Hebrews (3rd century AD: P655); The Shepherd of Hermas (3rd or 4th century: P404), and a work of Irenaeus, (3rd century: P405). There are many parts of other canonical books as well as many early Christian hymns, prayers, and letters also found among them.

All manuscripts classified as "theological" in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri are listed below. A few manuscripts that belong to multiple genres, or genres that are inconsistently treated in the volumes of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, are also included. For example, the quotation from Psalm 90 (P. Oxy. XVI 1928) associated with an amulet, is classified according to its primary genre as a magic text in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri; however, it is included here among witnesses to the Old Testament text. In each volume that contains theological manuscripts, they are listed first, according to an English tradition of academic precedence (see ).

Old Testament[]

The original Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) was translated into Greek between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC. This translation is called the Septuagint (or LXX, both 70 in Latin), because there is a tradition that seventy Jewish scribes compiled it in Alexandria. It was quoted in the New Testament and is found bound together with the New Testament in the 4th and 5th century Greek uncial codices Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Vaticanus. The Septuagint included books, called the Apocrypha or Deuterocanonical by Christians, which were later not accepted into the Jewish canon of sacred writings (see next section). Portions of Old Testament books of undisputed authority found among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri are listed in this section.

- The first number (Vol) is the volume of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri in which the manuscript is published.

- The second number (Oxy) is the overall publication sequence number in Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

- Standard abbreviated citation of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri is:

- P. Oxy. <volume in Roman numerals> <publication sequence number>.

- Context will always make clear whether volume 70 of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri or the Septuagint is intended.

- P. Oxy. VIII 1073 is an Old Latin version of Genesis, other manuscripts are probably copies of the Septuagint.

- Dates are estimated to the nearest 50 year increment.

- Content is given to the nearest verse where known.

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | 656 | 150 | Gen 14:21–23; 15:5–9; 19:32–20:11; 24:28–47; 27:32–33, 40–41 |

Bodleian Library; MS.Gr.bib.d.5(P) | Oxford | UK |

| VI | 845 | 400 | Psalms 68; 70 | Egyptian Museum; JE 41083 | Cairo | Egypt |

| VI | 846 | 550 | Amos 2 | University of Pennsylvania; E 3074 | Philadelphia Pennsylvania |

U.S. |

| VII | 1007 | 400 | Genesis 2-3 | British Museum; Inv. 2047 | London | UK |

| VIII | 1073 | 350 | Gen 5–6 Old Latin | British Museum; Inv. 2052 | London | UK |

| VIII | 1074 | 250 | Exodus 31–32 | University of Illinois; GP 1074 | Urbana, Illinois | U.S. |

| VIII | 1075 | 250 | Exodus 11:26–32 | British Library; Inv. 2053 (recto) | London | UK |

| IX | 1166 | 250 | Genesis 16:8–12 | British Library; Inv. 2066 | London | UK |

| IX | 1167 | 350 | Genesis 31 | Princeton Theological Seminary Pap. 9 |

Princeton New Jersey |

U.S. |

| IX | 1168 | 350 | Joshua 4-5 vellum | Princeton Theological Seminary Pap. 10 |

Princeton New Jersey |

U.S. |

| X | 1225 | 350 | Leviticus 16 | Princeton Theological Seminary Pap. 12 |

Princeton New Jersey |

U.S. |

| X | 1226 | 300 | Psalms 7–8 | Liverpool University Class. Gr. Libr. 4241227 |

Liverpool | UK |

| XI | 1351 | 350 | Lev 27 vellum | Ambrose Swasey Library; 886.4 Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School |

Rochester New York |

U.S. |

| XI | 1352 | 325 | Pss 82–83 vellum | Egyptian Museum; JE 47472 | Cairo | Egypt |

| XV | 1779 | 350 | Psalm 1 | United Theological Seminary | Dayton, Ohio | U.S. |

| XVI | 1928 | 500 | Ps 90 amulet | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2065 | 500 | Psalm 90 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2066 | 500 | Ecclesiastes 6–7 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXIV | 2386 | 500 | Psalms 83–84 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| L | 3522 | 50 | Job 42.11–12 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LX | 4011 | 550 | Ps 75 interlinear | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4442 | 225 | Ex 20:10–17, 18–22 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4443 | 100 | Esther 6–7 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

Old Testament Deuterocanon (or, Apocrypha)[]

This name designates several, unique writings (e.g., the Book of Tobit) or different versions of pre-existing writings (e.g., the Book of Daniel) found in the canon of the Jewish scriptures (most notably, in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Tanakh). Although those writings were no longer viewed as having a canonical status amongst Jews by the beginning of the second century A.D., they retained that status for much of the Christian Church. They were and are accepted as part of the Old Testament canon by the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox churches. Protestant Christians, however, follow the example of the Jews and do not accept these writings as part of the Old Testament canon.

- PP. Oxy. XIII 1594 and LXV 4444 are vellum ("vellum" noted in table).

- Both copies of Tobit are different editions to the known Septuagint text ("not LXX" noted in table).

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III | 403 | 400 | Apocalypse of Baruch 12–14 | St. Mark's Library General Theological Seminary |

New York City | U.S. |

| VII | 1010 | 350 | 2 Esdras 16:57–59 | Bodleian Library MS.Gr.bib.g.3(P) |

Oxford | UK |

| VIII | 1076 | 550 | Tobit 2 not LXX |

John Rylands University Library 448 |

Manchester | UK |

| XIII | 1594 | 275 | Tobit 12 vellum, not LXX |

Cambridge University Library Add.MS. 6363 |

Cambridge | UK |

| XIII | 1595 | 550 | Ecclesiasticus 1 |

Palestine Institute Museum Pacific School of Religion |

Berkeley California |

U.S. |

| XVII | 2069 | 400 | 1 Enoch 85.10–86.2, 87.1–3 | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XVII | 2074 | 450 | Apostrophe to Wisdom [?] | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| LXV | 4444 | 350 | Wisdom 4:17–5:1 vellum |

Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

[]

| Vol | Oxy | Date | Content | Institution | City, State | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IX | 1173 | 250 | Philo | Bodleian Library | Oxford | UK |

| XI | 1356 | 250 | Philo | Bodleian Library | Oxford | UK |

| XVIII | 2158 | 250 | Philo | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

| XXXVI | 2745 | 400 | onomasticon of Hebrew names | Ashmolean Museum | Oxford | UK |

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas