Syriac alphabet

| Syriac alphabet | |

|---|---|

Estrangela-styled alphabet | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1 AD – present |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Aramaic (Classical Syriac, Western Neo-Aramaic, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo, Christian Palestinian Aramaic), Arabic (Garshuni), Malayalam (Suriyani Malayalam), Sogdian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Sogdian

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Syrc, 135

|

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Syriac |

Unicode range |

|

The Syriac alphabet (ܐܠܦ ܒܝܬ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ ʾālep̄ bêṯ Sūryāyā[a]) is a writing system primarily used to write the Syriac language since the 1st century AD.[1] It is one of the Semitic abjads descending from the Aramaic alphabet through the Palmyrene alphabet,[2] and shares similarities with the Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic and Sogdian, the precursor and a direct ancestor of the traditional Mongolian scripts.

Syriac is written from right to left in horizontal lines. It is a cursive script where most—but not all—letters connect within a word. There is no letter case distinction between upper and lower case letters, though some letters change their form depending on their position within a word. Spaces separate individual words.

All 22 letters are consonants, although there are optional diacritic marks to indicate vowels and other features. In addition to the sounds of the language, the letters of the Syriac alphabet can be used to represent numbers in a system similar to Hebrew and Greek numerals.

Apart from Classical Syriac Aramaic, the alphabet has been used to write other dialects and languages. Several Christian Neo-Aramaic languages from Turoyo to the Northeastern Neo-Aramaic dialects of Assyrian and Chaldean, once vernaculars, primarily began to be written in the 19th century. The Serṭā variant specifically has recently been adapted to write Western Neo-Aramaic, traditionally written in a square Aramaic script closely related to the Hebrew alphabet. Besides Aramaic, when Arabic began to be the dominant spoken language in the Fertile Crescent after the Islamic conquest, texts were often written in Arabic using the Syriac script as knowledge of the Arabic alphabet was not yet widespread; such writings are usually called Karshuni or Garshuni (ܓܪܫܘܢܝ). In addition to Semitic languages, Sogdian was also written with Syriac script, as well as Malayalam, which form was called Suriyani Malayalam.

Alphabet forms[]

There are three major variants of the Syriac alphabet: ʾEsṭrangēlā, Maḏnḥāyā and Serṭā.

Classical ʾEsṭrangēlā[]

The oldest and classical form of the alphabet is ʾEsṭrangēlā[b] (ܐܣܛܪܢܓܠܐ). The name of the script is thought to derive from the Greek adjective strongýlē (στρογγύλη, 'rounded'),[3] though it has also been suggested to derive from serṭā ʾewwangēlāyā (ܣܪܛܐ ܐܘܢܓܠܝܐ, 'gospel character').[4] Although ʾEsṭrangēlā is no longer used as the main script for writing Syriac, it has received some revival since the 10th century. It is often used in scholarly publications (such as the Leiden University version of the Peshitta), in titles, and in inscriptions. In some older manuscripts and inscriptions, it is possible for any letter to join to the left, and older Aramaic letter forms (especially of ḥeṯ and the lunate mem) are found. Vowel marks are usually not used with ʾEsṭrangēlā, being the oldest form of the script and arising before the development of specialized diacritics.

East Syriac Maḏnḥāyā[]

The East Syriac dialect is usually written in the Maḏnḥāyā (ܡܲܕ݂ܢܚܵܝܵܐ, 'Eastern') form of the alphabet. Other names for the script include Swāḏāyā (ܣܘܵܕ݂ܵܝܵܐ, 'conversational' or 'vernacular', often translated as 'contemporary', reflecting its use in writing modern Neo-Aramaic), ʾĀṯōrāyā (ܐܵܬ݂ܘܿܪܵܝܵܐ, 'Assyrian', not to be confused with the traditional name for the Hebrew alphabet), Kaldāyā (ܟܲܠܕܵܝܵܐ, 'Chaldean'), and, inaccurately, "Nestorian" (a term that was originally used to refer to the Church of the East in the Sasanian Empire). The Eastern script resembles ʾEsṭrangēlā somewhat more closely than the Western script.

Vowels[]

The Eastern script uses a system of dots above and/or below letters, based on an older system, to indicate vowel sounds not found in the script:

- A dot above and a dot below a letter represent [a], transliterated as a or ă (called ܦܬ݂ܵܚܵܐ, pṯāḥā),

- Two diagonally-placed dots above a letter represent [ɑ], transliterated as ā or â or å (called ܙܩܵܦ݂ܵܐ, zqāp̄ā),

- Two horizontally-placed dots below a letter represent [ɛ], transliterated as e or ĕ (called ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܪܝܼܟ݂ܵܐ, rḇāṣā ʾărīḵā or ܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܦܫܝܼܩܵܐ, zlāmā pšīqā; often pronounced [ɪ] and transliterated as i in the East Syriac dialect),

- Two diagonally-placed dots below a letter represent [e], transliterated as ē (called ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܟܲܪܝܵܐ, rḇāṣā karyā or ܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܩܲܫܝܵܐ, zlāmā qašyā),

- The letter waw with a dot below it represents [u], transliterated as ū or u (called ܥܨܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܠܝܼܨܵܐ, ʿṣāṣā ʾălīṣā or ܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ, rḇāṣā),

- The letter waw with a dot above it represents [o], transliterated as ō or o (called ܥܨܵܨܵܐ ܪܘܝܼܚܵܐ, ʿṣāṣā rwīḥā or ܪܘܵܚܵܐ, rwāḥā),

- The letter yōḏ with a dot beneath it represents [i], transliterated as ī or i (called ܚܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ, ḥḇāṣā),

- A combination of rḇāṣā karyā (usually) followed by a letter yōḏ represents [e] (possibly *[e̝] in Proto-Syriac), transliterated as ē or ê (called ܐܲܣܵܩܵܐ, ʾăsāqā).

It is thought that the Eastern method for representing vowels influenced the development of the niqqud markings used for writing Hebrew.

In addition to the above vowel marks, transliteration of Syriac sometimes includes ə, e̊ or superscript e (or often nothing at all) to represent an original Aramaic schwa that became lost later on at some point in the development of Syriac. Some transliteration schemes find its inclusion necessary for showing spirantization or for historical reasons. Whether because its distribution is mostly predictable (usually inside a syllable-initial two-consonant cluster) or because its pronunciation was lost, both the East and the West variants of the alphabet traditionally have no sign to represent the schwa.

West Syriac Serṭā[]

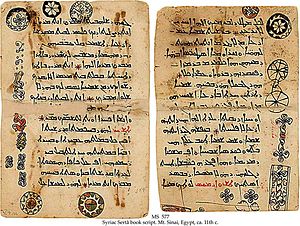

The West Syriac dialect is usually written in the Serṭā or Serṭo (ܣܶܪܛܳܐ, 'line') form of the alphabet, also known as the Pšīṭā (ܦܫܺܝܛܳܐ, 'simple'), 'Maronite' or the 'Jacobite' script (although the term Jacobite is considered derogatory). Most of the letters are clearly derived from ʾEsṭrangēlā, but are simplified, flowing lines. A cursive chancery hand is evidenced in the earliest Syriac manuscripts, but important works were written in ʾEsṭrangēlā. From the 8th century, the simpler Serṭā style came into fashion, perhaps because of its more economical use of parchment.

Vowels[]

The Western script is usually vowel-pointed, with miniature Greek vowel letters above or below the letter which they follow:

- (ـܱܰ) Capital alpha (Α) represents [a], transliterated as a or ă (ܦܬ݂ܳܚܳܐ, pṯāḥā),

- (ـܴܳ) Lowercase alpha (α) represents [ɑ], transliterated as ā or â or å (ܙܩܳܦ݂ܳܐ, Zqāp̄ā; pronounced as [o] and transliterated as o in the West Syriac dialect),

- (ـܷܶ) Lowercase epsilon (ε) represents both [ɛ], transliterated as e or ĕ, and [e], transliterated as ē (ܪܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ, Rḇāṣā),

- (ـܻܺ) Capital eta (H) represents [i], transliterated as ī (ܚܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ, Ḥḇāṣā),

- (ـܾܽ) A combined symbol of capital upsilon (Υ) and lowercase omicron (ο) represents [u], transliterated as ū or u (ܥܨܳܨܳܐ, ʿṣāṣā),

- Lowercase omega (ω), used only in the vocative interjection ʾō (ܐܘّ, 'O!').

Summary table[]

The Syriac alphabet consists of the following letters, shown in their isolated (non-connected) forms. When isolated, the letters kāp̄, mīm, and mūn are usually shown with their initial form connected to their final form (see below). The letters ʾālep̄, dālaṯ, hē, waw, zayn, ṣāḏē, rēš and taw (and, in early ʾEsṭrangēlā manuscripts, the letter semkaṯ[5]) do not connect to a following letter within a word; these are marked with an asterisk (*).

| Letter | Sound Value (Classical Syriac) | Numerical Value |

Phoenician Equivalent |

Imperial Aramaic Equivalent |

Hebrew Equivalent |

Arabic

Equivalent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Translit. | ʾEsṭrangēlā (classical) |

Maḏnḥāyā (eastern) |

Serṭā (western) |

Unicode

(typing) |

Transliteration | IPA | |||||

| *ܐܠܦ | ʾĀlep̄*[c] | ܐ | ʾ or null mater lectionis: ā |

[ʔ] or ∅ mater lectionis: [ɑ] |

1 | |||||||