Semitic languages

| Semitic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | West Asia, North Africa, Horn of Africa, Caucasus, Malta |

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Semitic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | sem |

| Glottolog | semi1276 |

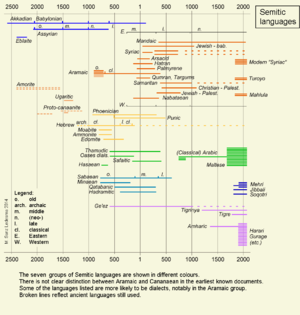

Approximate historical distribution of Semitic languages | |

Chronology mapping of Semitic languages | |

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family originating in West Asia.[1] They are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of West Asia, and latterly also North Africa, the Horn of Africa, Malta, in small pockets in the Caucasus[2] as well as in often large immigrant and expatriate communities in North America, Europe, and Australasia.[3][4] The terminology was first used in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen School of History,[5] who derived the name from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis.

The most widely spoken Semitic languages today, with numbers of native speakers only, are Arabic (300 million),[6] Amharic (~22 million),[7] Tigrinya (7 million),[8] Hebrew (~5 million native/L1 speakers),[9] Tigre (~1.05 million), Aramaic (575,000 to 1 million largely Assyrian speakers)[10][11][12] and Maltese (483,000 speakers).[13]

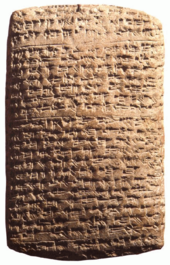

Semitic languages occur in written form from a very early historical date in West Asia, with East Semitic Akkadian and Eblaite texts (written in a script adapted from Sumerian cuneiform) appearing from the 30th century BCE and the 25th century BCE in Mesopotamia and the north eastern Levant respectively. The only earlier attested languages are Sumerian, Elamite (2800 BCE to 550 BCE), both language isolates, Egyptian, and the unclassified Lullubi (30th century BCE). Amorite appeared in Mesopotamia and the northern Levant circa 2000 BC, followed by the mutually intelligible Canaanite languages (including Hebrew, Moabite, Edomite, Phoenician, Ekronite, Ammonite, Amalekite and Sutean), the still spoken Aramaic and Ugaritic during the 2nd millenium BC.

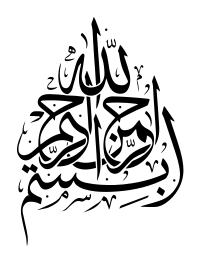

Most scripts used to write Semitic languages are abjads – a type of alphabetic script that omits some or all of the vowels, which is feasible for these languages because the consonants are the primary carriers of meaning in the Semitic languages. These include the Ugaritic, Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, and ancient South Arabian alphabets. The Geʽez script, used for writing the Semitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea, is technically an abugida – a modified abjad in which vowels are notated using diacritic marks added to the consonants at all times, in contrast with other Semitic languages which indicate diacritics based on need or for introductory purposes. Maltese is the only Semitic language written in the Latin script and the only Semitic language to be an official language of the European Union.

The Semitic languages are notable for their nonconcatenative morphology. That is, word roots are not themselves syllables or words, but instead are isolated sets of consonants (usually three, making a so-called triliteral root). Words are composed out of roots not so much by adding prefixes or suffixes, but rather by filling in the vowels between the root consonants (although prefixes and suffixes are often added as well). For example, in Arabic, the root meaning "write" has the form k-t-b. From this root, words are formed by filling in the vowels and sometimes adding additional consonants, e.g. كتاب kitāb "book", كتب kutub "books", كاتب kātib "writer", كتّاب kuttāb "writers", كتب kataba "he wrote", يكتب yaktubu "he writes", etc.

Name and identification[]

The similarity of the Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic languages has been accepted by all scholars since medieval times. The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Near Eastern countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel.[14] Almost two centuries later, Hiob Ludolf described the similarities between these three languages and the Ethiopian Semitic languages.[14] However, neither scholar named this grouping as "Semitic".[14]

The term "Semitic" was created by members of the Göttingen School of History, and specifically by August Ludwig von Schlözer[15] (1781).[16] Johann Gottfried Eichhorn[17] (1787)[18] coined the name "Semitic" in the late 18th century to designate the languages closely related to Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew.[15] The choice of name was derived from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the genealogical accounts of the biblical Book of Genesis,[15] or more precisely from the Koine Greek rendering of the name, Σήμ (Sēm). Eichhorn is credited with popularising the term,[19] particularly via a 1795 article "Semitische Sprachen" (Semitic languages) in which he justified the terminology against criticism that Hebrew and Canaanite were the same language despite Canaan being "Hamitic" in the Table of Nations.[20][19]

In the Mosaic Table of Nations, those names which are listed as Semites are purely names of tribes who speak the so-called Oriental languages and live in Southwest Asia. As far as we can trace the history of these very languages back in time, they have always been written with syllabograms or with alphabetic script (never with hieroglyphs or pictograms); and the legends about the invention of the syllabograms and alphabetic script go back to the Semites. In contrast, all so called Hamitic peoples originally used hieroglyphs, until they here and there, either through contact with the Semites, or through their settlement among them, became familiar with their syllabograms or alphabetic script, and partly adopted them. Viewed from this aspect too, with respect to the alphabet used, the name "Semitic languages" is completely appropriate.

Previously these languages had been commonly known as the "Oriental languages" in European literature.[15][17] In the 19th century, "Semitic" became the conventional name; however, an alternative name, "Syro-Arabian languages", was later introduced by James Cowles Prichard and used by some writers.[17]

History[]

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples[]

There are several locations proposed as possible sites for prehistoric origins of Semitic-speaking peoples: Mesopotamia, the Levant, East Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa. Some view that the Semitic originated in the Levant circa 3800 BC, and was later also introduced to the Horn of Africa in approximately 800 BC from the southern Arabian peninsula, and to North Africa via Phoenician colonists at approximately the same time.[21][22] Some assign the arrival of Semitic speakers in the Horn of Africa to a much earlier date.[23]

Semitic languages were spoken and written across much of the Middle East and Asia Minor during the Bronze Age and Iron Age, the earliest attested being the East Semitic Akkadian of the Mesopotamian, northeast Levantine and southeastern Anatolian polities of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia (effectively modern Iraq, southeast Turkey and northeast Syria), and the also East Semitic Eblaite language of the kingdom of Ebla in the northeastern Levant.

The various extremely closely related and mutually intelligible Canaanite languages, a branch of the Northwest Semitic languages included Amorite, first attested in the 21st century BC, Edomite, Hebrew, Ammonite, Moabite, Phoenician (Punic/Carthaginian), Samaritan Hebrew, Ekronite, Amalekite and Sutean. They were spoken in what is today Israel, Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, the northern Sinai peninsula, some northern and eastern parts of the Arabian peninsula, southwest fringes of Turkey, and in the case of Phoenician, coastal regions of Tunisia (Carthage), Libya and Algeria, and possibly in Malta and other Mediterranean islands.

Ugaritic, a Northwest Semitic language closely related to but distinct from the Canaanite group was spoken in the kingdom of Ugarit in north western Syria.

A hybrid Canaano-Akkadian language also emerged in Canaan (Israel, Jordan, Lebanon) during the 14th century BC, incorporating elements of the Mesopotamian East Semitic Akkadian language of Assyria and Babylonia with the West Semitic Canaanite languages.[24]

Aramaic, a still living ancient Northwest Semitic language, first attested in the 12th century BC in the northern Levant, gradually replaced the East Semitic and Canaanite languages across much of the Near East, particularly after being adopted as the lingua franca of the vast Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC) by Tiglath-Pileser III during the 8th century BC, and being retained by the succeeding Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid Empires.[25]

The Chaldean language (not to be confused with Aramaic or its Biblical variant, sometimes referred to as Chaldean) was a Northwest Semitic language also, possibly closely related to Aramaic, but no examples of the language remain, as after settling in south eastern Mesopotamia from the Levant during the 9th century BC the Chaldeans appear to have rapidly adopted the Akkadian and Aramaic languages of the indigenous Mesopotamians.

Old South Arabian languages (classified as South Semitic and therefore distinct from the Central Semitic language of Arabic which developed over 1000 years later) were spoken in the kingdoms of Dilmun, Meluhha, Sheba, Ubar, Socotra and Magan, which in modern terms encompassed part of the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain, Qatar, Oman and Yemen.[citation needed] South Semitic languages are thought to have spread to the Horn of Africa circa 8th century BC where the Ge'ez language emerged (though the direction of influence remains uncertain).

Common Era (CE)[]

Syriac, a 5th-century BC Assyrian[26] Mesopotamian descendant of Aramaic used in northeastern Syria, Mesopotamia and south east Anatolia,[27] rose to importance as a literary language of early Christianity in the third to fifth centuries and continued into the early Islamic era.

The Arabic language, although originating in the Arabian peninsula, first emerged in written form in the 1st to 4th centuries CE in the southern regions of present-day Jordan, Israel, Palestine, and Syria. With the advent of the early Arab conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries, Classical Arabic eventually replaced many (but not all) of the indigenous Semitic languages and cultures of the Near East. Both the Near East and North Africa saw an influx of Muslim Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula, followed later by non-Semitic Muslim Iranian and Turkic peoples. The previously dominant Aramaic dialects maintained by the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians gradually began to be sidelined, however descendant dialects of Eastern Aramaic (including the Akkadian influenced Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo and Mandaic) survive to this day among the Assyrians and Mandaeans of northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, with up to a million fluent speakers. Western Aramaic is now only spoken by a few thousand Aramean Syriac Christians in western Syria. The Arabs spread their Central Semitic language to North Africa (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and northern Sudan and Mauritania), where it gradually replaced Egyptian Coptic and many Berber languages (although Berber is still largely extant in many areas), and for a time to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain, Portugal and Gibraltar) and Malta.

With the patronage of the caliphs and the prestige of its liturgical status, Arabic rapidly became one of the world's main literary languages. Its spread among the masses took much longer, however, as many (although not all) of the native populations outside the Arabian Peninsula only gradually abandoned their languages in favour of Arabic. As Bedouin tribes settled in conquered areas, it became the main language of not only central Arabia, but also Yemen,[28] the Fertile Crescent, and Egypt. Most of the Maghreb followed, specifically in the wake of the Banu Hilal's incursion in the 11th century, and Arabic became the native language of many inhabitants of al-Andalus. After the collapse of the Nubian kingdom of Dongola in the 14th century, Arabic began to spread south of Egypt into modern Sudan; soon after, the Beni Ḥassān brought Arabization to Mauritania. A number of Modern South Arabian languages distinct from Arabic still survive, such as Soqotri, Mehri and Shehri which are mainly spoken in Socotra, Yemen and Oman.

Meanwhile, the Semitic languages that had arrived from southern Arabia in the 8th century BC were diversifying in Ethiopia and Eritrea, where, under heavy Cushitic influence, they split into a number of languages, including Amharic and Tigrinya. With the expansion of Ethiopia under the Solomonic dynasty, Amharic, previously a minor local language, spread throughout much of the country, replacing both Semitic (such as Gafat) and non-Semitic (such as Weyto) languages, and replacing Ge'ez as the principal literary language (though Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for Christians in the region); this spread continues to this day, with Qimant set to disappear in another generation.

Present situation[]

Arabic is currently the native language of majorities from Mauritania to Oman, and from Iraq to the Sudan. Classical Arabic is the language of the Quran. It is also studied widely in the non-Arabic-speaking Muslim world. The Maltese language is genetically a descendant of the extinct Siculo-Arabic, a variety of Maghrebi Arabic formerly spoken in Sicily. The modern Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin script with the addition of some letters with diacritic marks and digraphs. Maltese is the only Semitic official language within the European Union.

Successful as second languages far beyond their numbers of contemporary first-language speakers, a few Semitic languages today are the base of the sacred literature of some of the world's major religions, including Islam (Arabic), Judaism (Hebrew and Aramaic), churches of Syriac Christianity (Syriac) and Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Christianity (Ge'ez). Millions learn these as a second language (or an archaic version of their modern tongues): many Muslims learn to read and recite the Qur'an and Jews speak and study Biblical Hebrew, the language of the Torah, Midrash, and other Jewish scriptures. Ethnic Assyrian followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Ancient Church of the East, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church and Assyrian members of the Syriac Orthodox Church both speak Mesopotamian eastern Aramaic and use it also as a liturgical tongue. The language is also used liturgically by the primarily Arabic-speaking followers of the Maronite, Syriac Catholic Church and some Melkite Christians. Greek and Arabic are the main liturgical languages of Oriental Orthodox Christians in the Middle East, who compose the patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Mandaic is both spoken and used as a liturgical language by the Mandaeans.

Despite the ascendancy of Arabic in the Middle East, other Semitic languages still exist. Biblical Hebrew, long extinct as a colloquial language and in use only in Jewish literary, intellectual, and liturgical activity, was revived in spoken form at the end of the 19th century. Modern Hebrew is the main language of Israel, with Biblical Hebrew remaining as the language of liturgy and religious scholarship of Jews worldwide.

Several smaller ethnic groups, in particular the Assyrians, Kurdish Jews, and Gnostic Mandeans, continue to speak and write Mesopotamian Aramaic languages, particularly Neo-Aramaic languages descended from Syriac, in those areas roughly corresponding to Kurdistan (northern Iraq, northeast Syria, south eastern Turkey and northwestern Iran). Syriac language itself, a descendant of Eastern Aramaic languages (Mesopotamian Old Aramaic), is used also liturgically by the Syriac Christians throughout the area. Although the majority of Neo-Aramaic dialects spoken today are descended from Eastern varieties, Western Neo-Aramaic is still spoken in 3 villages in Syria.

In Arab-dominated Yemen and Oman, on the southern rim of the Arabian Peninsula, a few tribes continue to speak Modern South Arabian languages such as Mahri and Soqotri. These languages differ greatly from both the surrounding Arabic dialects and from the (unrelated but previously thought to be related) languages of the Old South Arabian inscriptions.

Historically linked to the peninsular homeland of Old South Arabian, of which only one language, Razihi, remains, Ethiopia and Eritrea contain a substantial number of Semitic languages; the most widely spoken are Amharic in Ethiopia, Tigre in Eritrea, and Tigrinya in both. Amharic is the official language of Ethiopia. Tigrinya is a working language in Eritrea. Tigre is spoken by over one million people in the northern and central Eritrean lowlands and parts of eastern Sudan. A number of Gurage languages are spoken by populations in the semi-mountainous region of central Ethiopia, while Harari is restricted to the city of Harar. Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for certain groups of Christians in Ethiopia and in Eritrea.

Phonology[]

The phonologies of the attested Semitic languages are presented here from a comparative point of view. See Proto-Semitic language#Phonology for details on the phonological reconstruction of Proto-Semitic used in this article. The reconstruction of Proto-Semitic (PS) was originally based primarily on Arabic, whose phonology and morphology (particularly in Classical Arabic) is very conservative, and which preserves as contrastive 28 out of the evident 29 consonantal phonemes.[29] with *s [s] and *š [ʃ] merging into Arabic /s/ ⟨س⟩ and *ś [ɬ] becoming Arabic /ʃ/ ⟨ش⟩.

| Type | Labial | Inter-dental | Dental/ | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral | ||||||||

| Nasal | *m [m] | *n [n] | |||||||

| Stop | emphatic | *ṭ / *θ [tʼ] | *ḳ / *q [kʼ] | ||||||

| voiceless | *p [p] | *t [t] | *k [k] | *ʼ [ʔ] | |||||

| voiced | *b [b] | *d [d] | *g [ɡ] | ||||||

| Fricative | emphatic | *ṱ[a] / *θ̠ [θʼ] | *ṣ [s’] | *ṣ́ [ɬʼ] | |||||

| voiceless | *ṯ [θ] | *s [s] | *ś [ɬ] | *š [ʃ] | *ḫ [x]~[χ] | *ḥ [ħ] | *h [h] | ||

| voiced | *ḏ [ð] | *z [z] | *ġ [ɣ]~[ʁ] | *ʻ [ʕ] | |||||

| Trill | *r [r] | ||||||||

| Approximant | *l [l] | *y [j] | *w [w] | ||||||

| |||||||||

Note: the fricatives *s, *z, *ṣ, *ś, *ṣ́, *ṱ may also be interpreted as affricates (/t͡s/, /d͡z/, /t͡sʼ/, /t͡ɬ/, /t͡ɬʼ/, /t͡θʼ/), as discussed in Proto-Semitic language § Fricatives.

This comparative approach is natural for the consonants, as sound correspondences among the consonants of the Semitic languages are very straightforward for a family of its time depth. Sound shifts affecting the vowels are more numerous and, at times, less regular.

Consonants[]

Each Proto-Semitic phoneme was reconstructed to explain a certain regular sound correspondence between various Semitic languages. Note that Latin letter values (italicized) for extinct languages are a question of transcription; the exact pronunciation is not recorded.

Most of the attested languages have merged a number of the reconstructed original fricatives, though South Arabian retains all fourteen (and has added a fifteenth from *p > f).

In Aramaic and Hebrew, all non-emphatic stops occurring singly after a vowel were softened to fricatives, leading to an alternation that was often later phonemicized as a result of the loss of gemination.

In languages exhibiting pharyngealization of emphatics, the original velar emphatic has rather developed to a uvular stop [q].

| Proto Semitic |

IPA | Arabic | Maltese | Akka- dian |

Ugaritic | Phoenician | Hebrew | Aramaic | Ge'ez | Tigrinya | Amharic14 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Written | Classical[32] | Modern | Written | Pronounce | Written | Pronounce | Written | Translit. | Pronounce | Written | Biblical | Tiberian | Modern | Imperial | Syriac | Translit. | ||||||||||||||||

| *b | [b] | ب | b | /b/ | b | /b/ | b | |||||||||||||||||||||||||