Padania

Padania | |

|---|---|

Flag  Seal | |

Map of the Po river basin. | |

| Country | Italy |

| Area | |

| • Total | 124,000 km2 (48,000 sq mi) |

| Population (2014) | |

| • Total | 27,800,000 |

| • Density | 220/km2 (580/sq mi) |

Padania (/pəˈdeɪniə/, also UK: /-ˈdɑːn-/,[1] Italian: [paˈdaːnja]) is an alternative name and proposed independent state encompassing Northern Italy, derived from the name of the Po River (Latin Padus), whose basin includes much of the region, centered on the Po Valley (Pianura Padana), the major plain of Northern Italy.

Coined in the 1960s as a geographical term roughly corresponding to historical Cisalpine Gaul, the term was popularised beginning in the early 1990s, when Lega Nord, a federalist and, at times, separatist political party in Italy, proposed it as a possible name for an independent state. Since then it has been strongly associated with "Padanian nationalism" and North Italian separatism.[2] Padania as defined in Lega Nord's 1996 Declaration of Independence and Sovereignty of Padania goes beyond Northern Italy and includes much of Central Italy, for a greater Padania that includes more than half of the Republic of Italy (161,000 of 301,000 km2 in area, 34 million out of 60 million in population).

Etymology[]

The adjective padano is derived from Padus, the Latin name of the Po River. The French client republics in the Po Valley during the Napoleonic era included the Cispadane Republic and the Transpadane Republic, according to the custom (emerged with the French Revolution) of naming territories on the basis of watercourses. The ancient Regio XI (the region of the Roman Empire on the current territory of the Aosta Valley, Piedmont and Lombardy) has been referred to as Regio XI Transpadana only in modern historiography.

The terms Pianura Padana or Val Padana are the standard denominations in geography textbooks and atlases, but the derivation Padania was coined only in the 1960s.

Journalist Gianni Brera from the 1960s used the term Padania to indicate the area that at the time of Cato the Elder corresponded to Cisalpine Gaul.[3] In the same years and later, the term Padania was considered a geographic synonym of Po Valley and as such was included in the Enciclopedia Universo in 1965[4] and in the Devoto–Oli dictionary of the Italian language in 1971. The term was also used in Italian dialectology, in relation to Gallo-Italic languages, and sometimes even extended to all regional languages distinguishing Northern from Central Italy along the La Spezia–Rimini Line.[5]

Macroregion[]

The first use of Padania in socio-economic terms dates from 1975, when Guido Fanti, the Communist President of Emilia-Romagna, proposed a union composed of Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont and Liguria.[6][7] The term was seldom used in these terms until the Giovanni Agnelli Foundation re-launched it in 1992 through the volume La Padania, una regione italiana in Europa (English: Padania, an Italian region in Europe), written by various academics.[8]

In 1990 Gianfranco Miglio, a political scientist who would be elected senator for Lega Nord in 1992 and 1994, wrote a book in which he described a draft constitutional reform. According to Miglio, Padania (consisting of five regions: Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria and Emilia-Romagna) would become one of the three hypothetical macroregions of a future Italy, along with Etruria (Central Italy) and Mediterranea (Southern Italy), while the autonomous regions (Aosta Valley, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Sicily and Sardinia) would be left with their current autonomy.[9]

In political science[]

Gilberto Oneto, a student of Miglio without any academic credentials, in the 1990s researched northern traditions and culture to find evidence of the existence of a common Padanian heritage.[10][11] Historian and linguist Sergio Salvi (2014) has also defended the concept of Padania.[12]

In 1993 Robert D. Putnam, a political scientist at Harvard University, wrote a book titled Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, in which he spoke of a "civic North", defined according to the inhabitants' civic traditions and attitudes, and explained its social peculiarities to the historical emergence of the free medieval communes since the 10th century.[13]

Lega Nord's definition of Padania's boundaries is similar to Putnam's "civic North", which also includes the central Italian regions of Tuscany, Marche and Umbria. Stefano Galli, a political scientist close to the party and columnist for Il Giornale and La Padania, has called Putnam's theory a source for defining Padania.[14] According to the Galli, these regions share similar patterns of civil society, citizenship, and government with the North.[15]

The existence of a "Padanian nation" has been however criticised by a number of organisations and individuals in Italy, from the Italian Geographical Society[16] to historian , who is a supporter of Venetian nationalism instead.[17] , a political scientist, once explained that, even though a "Padanian nation" does not exist yet, it might well emerge as all nations are ultimately human inventions.[18]

Padanian nationalism[]

Lega Nord, a political party created in 1991 by the union of several northern regional parties (including Lega Lombarda and Liga Veneta), used the term for a larger geographical range than the Po Valley proper, or the macroregion proposed by Fanti in the 1970s.

Since 1991, Lega Nord has promoted either secession or larger autonomy for Padania, and has created a flag and a national anthem to this effect.[19] In 1996, the "Federal Republic of Padania" was proclaimed.[20] Subsequently, in 1997, Lega Nord created an unofficial Padanian parliament in Mantua and organised elections for it. Lega Nord also chose a national anthem: the Va, pensiero chorus from Giuseppe Verdi's Nabucco, in which the exiled Hebrew slaves lament their lost homeland.

The term Padania has been also used in politics by other nationalist/separatist parties and groups, including Lega Padana, Lega Padana Lombardia, the Padanian Union, the Alpine Padanian Union, Veneto Padanian Federal Republic and the .[21]

Lega Nord's Padania[]

Proper Padania, claimed by Lega Padana, excludes Tuscany (except for Massa-Carrara province and Tuscan Romagna), Umbria and Marche (except for the Gallo-picene speaking areas in the north of the region)

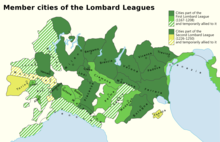

According to Lega Nord's Declaration of Independence and Sovereignty of Padania,[22] Padania is composed of 14 "nations" (Lombardy, Veneto, Piedmont, Tuscany, Emilia, Liguria, Marche, Romagna, Umbria, Friuli, Trentino, South Tyrol, Venezia Giulia, Aosta Valley), encompassing both Northern and Central Italy and slightly differing from Gianfranco Miglio's project.[9] The current 11 regions of Italy forming Padania, according to the party, are listed below:

| Region | Population (millions, 2016)[23] |

Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|

| Lombardy | 10.0 | 23,865 |

| Veneto | 4.9 | 18,391 |

| Emilia-Romagna (Emilia and Romagna) |

4.5 | 22,451 |

| Piedmont | 4.4 | 25,399 |

| Liguria | 1.6 | 5,422 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia (Friuli and Venezia Giulia) |

1.2 | 7,845 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol (Trentino and South Tyrol) |

1.1 | 13,607 |

| Aosta Valley | 0.1 | 3,263 |

| Northern Italy | 27.7 | 120,243 |

| Tuscany | 3.8 | 22,993 |

| Marche | 1.6 | 9,366 |

| Umbria | 0.9 | 8,456 |

| Padania (total) | 33.9 | 161,076 |

Flag of Padania[]

The "Sun of the Alps" is the unofficial flag of Padania and the symbol of the Padanian nationalism. The flag has a green stylized sun on a white background. It resembles ancient ornaments which are found in the art and culture of the area, like one example of Etruscan art from the 7th century BC found at Civitella Paganico.[24] The flag was created in the 1990s and was adopted by Lega Nord upon their declaration of Padanian independence.[25][26]

In its previous version, the flag included a red St George's Cross and a smaller Sun of the Alps in the upper part.[25]

Opinion polling[]

While support for a federal system, as opposed to a centrally administered state, receives widespread consensus within Padania, support for independence is less favoured. One poll in 1996 estimated that 52.4% of interviewees from Northern Italy considered secession advantageous (vantaggiosa) and 23.2% both advantageous and desirable (auspicabile).[27] Another poll in 2000 estimated that about 20% of "Padanians" (18.3% in North-West Italy and 27.4% in North-East Italy) supported secession in case Italy was not reformed into a federal state.[28]

According to a poll conducted in February 2010 by GPG, 45% of Northerners support the independence of Padania.[29] A poll conducted by in June 2010 puts that figure at 61% of Northerners (with 80% of them supporting at least federal reform), while noting that 55% of Italians consider Padania as only a political invention, against 42% believing in its real existence (45% of the sample being composed of Northerners, 19% of Central Italians and 36% of Southerners). As for federal reform, according to the poll, 58% of Italians support it.[30][31] A more recent poll by puts the support for fiscal federalism and secession respectively at 68% and 37% in Piedmont and Liguria, 77% and 46% in Lombardy, 81% and 55% in Triveneto (comprising Veneto), 63% and 31% in Emilia-Romagna, 51% and 19% in Central Italy (not including Lazio).[32]

In business[]

- Cassa Padana, Italian cooperative bank

- Banca Centropadana, Italian cooperative bank

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Padania" (US) and "Padania". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Squires, Nick (2011-08-23). "Silvio Berlusconi ally says Italy 'condemned to death'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Brera, Gianni (1993). Storie dei Lombardi. Milan: Baldini & Castoldi. p. 421. ISBN 88-85989-27-6.. Brera, Gianni. "Invectiva ad Patrem Padum". Guerin Sportivo. Milan.

- ^ "Italia". Enciclopedia Universo – vol. VII. Novara: De Agostini. 1965. pp. 196–197.

- ^ Hull, Geoffrey, PhD thesis 1982 (University of Sydney), published as The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis, 2017.

- ^ Santini, Francesco (1975-11-06). "Fanti spiega la sua proposta per una grande "lega del Po"". Turin: La Stampa.

- ^ "Addio a Guido Fanti, inventore della "Lega del Po"". Milan: L'Indipendenza. 2012-02-12. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13.

- ^ Bracalini, Paolo (25 June 2010). "La Padania? L'ha inventata la Fondazione Agnelli". Milan: il Giornale.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miglio, Gianfranco (1990). Una Costituzione per i prossimi trent'anni. Intervista sulla terza Repubblica. Rome-Bari: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-3685-4.

- ^ Oneto, Gilberto (1994). Bandiere di libertà: Simboli e vessilli dei Popoli dell'Italia settentrionale. Florence: Alinea.

- ^ Oneto, Gilberto (1997). L'invenzione della Padania. : Foedus.Oneto, Gilberto (2010). Il sole delle Alpi. Mito, storia e realtà di un simbolo antico. Turin: Il Cerchio.Oneto, Gilberto (2012). Polentoni o padani? Apologia di un popolo di egoisti xenofobi ignoranti ed evasori. Turin: Il Cerchio. La Libera Compagnia Padana

- ^ Viva La Grande Nazione Catalana E Anche Quella Padana | L'Indipendenza Archived 2014-01-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guiso, Luigi; Sapienza, Paola; Zingales, Luigi (2016). "Long-Term Persistence". Journal of the European Economic Association. 14 (6): 1401–1436. doi:10.1111/jeea.12177.

- ^ Galli, Stefano (2011-03-28). "Il commento Fini si rassegni, la Padania esiste davvero". Milan: il Giornale.

- ^ Riotta, Gianni (1993-02-12). "L'Italia fatta a pezzi". Milan: Corriere della Sera.

- ^ Rapporto annuale 2010

- ^ [1] Archived November 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ La questione non e' padana - Corriere della Sera

- ^ Oneto, Gilberto (1997). L'invenzione della Padania. Berbenno: Foedus Editore.

- ^ , Dalla Łiga alla Lega. Storia, movimenti, protagonisti, Marsilio, Venice 2009, p. 103

- ^ Jori, Francesco (2009). Dalla Łiga alla Lega. Storia, movimenti, protagonisti. Venice: Marsilio.

- ^ Lega Nord (15 September 1996). "Dichiarazione di indipendenza e sovranità della Padania" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2006.

- ^ istat.it (2016).

- ^ "Archeologia: ...in Toscana" (in Italian).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Araldica e Bandiere della Federazione Padana Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, Angelo Veronesi.

- ^ Movimento Giovani Padani (ed.). "Dichiarazione di indipendenza e sovranità della Padania". Archived from the original on 2013-05-12.

- ^ Diamanti, Ilvo (1 January 1996). "Il Nord senza Italia?". Limes. L'Espresso.[failed verification]

- ^ , 23 August 2000.[failed verification]

- ^ GPG (2009-02-12). "I sondaggi di GPG: Simulazione Referendum - Nord Italia". Il-liberale.blogspot. Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ (2010-06-25). "Federalismo e secessione" (PDF). . Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- ^ (2010-06-28). "Gli italiani non credono nella Padania. Ma al Nord prevale il sì alla secessione". .

- ^ GPG (2011-05-25). "Sondaggi GPG: Quesiti/2 - Maggio 2011". ScenariPolitici.com.

Further reading[]

- Diamanti, Ilvo (1996). Il male del Nord. Lega, localismo, secessione. Rome: Donzelli Editore. ISBN 88-7989-268-1.

- Gomez-Reino Cachafeiro, Margarita (2002). Ethnicity and Nationalism in Italian Politics. Inventing the Padania: Lega Nord and the Northern Question. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-1655-X.

- Hull, Geoffrey (2017). The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. 2 vols. Sydney: . ISBN 978-1-64007-053-0.

- Huysseune, Michel (2006). Modernity and secession. The social sciences and the political discourse of the Lega Nord in Italy. Oxford: Berg Publishers. ISBN 1-84545-061-2.

- Mainardi, Roberto (1998). L'Italia delle regioni. Il Nord e la Padania. Milan: Bruno Mondadori. ISBN 88-424-9442-9.

External links[]

- Geographical, historical and cultural regions of Italy

- Politics of Italy

- Proposed countries

- Separatism in Italy